Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Eastern Catholic Churches

View on Wikipedia| Eastern Catholic Churches | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: St. George's Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral, Melkite Greek Catholic Patriarchal Cathedral of the Dormition of Our Lady, Kidane Mehret Eritrean Catholic Cathedral, Armenian Catholic Cathedral of Saint Elias and Saint Gregory the Illuminator, St. Mary's Syro-Malankara Catholic Cathedral, Syro-Malabar Catholic Basilica of St. Mary | |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Eastern Christianity |

| Scripture | Bible (Septuagint, Peshitta) |

| Theology | Catholic theology and Eastern theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Structure | Communion |

| Pope | Leo XIV |

| Language | Koine Greek, Syriac, Hebrew, Aramaic, Geʽez, Coptic, Classical Armenian, Church Slavonic, Arabic, and vernaculars (Albanian, Hungarian, Romanian, Georgian, Malayalam, etc.) |

| Liturgy | Eastern Catholic liturgies |

| Separated from | Various autocephalous churches of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Church of the East throughout the centuries |

| Branched from | Catholic Church |

| Members | 18 million[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Particular churches sui iuris of the Catholic Church |

|---|

| Particular churches are grouped by liturgical rite |

| Alexandrian Rite |

| Armenian Rite |

| Byzantine Rite |

| East Syriac Rite |

| Latin liturgical rites |

| West Syriac Rite |

|

Eastern Catholic Churches Eastern Catholic liturgy |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

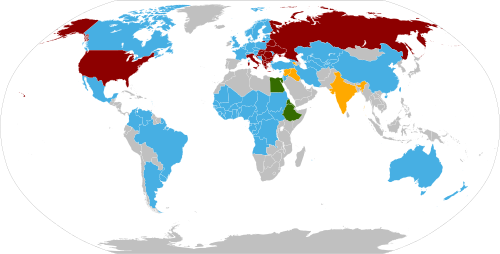

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches,[a] are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (sui iuris) particular churches of the Catholic Church in full communion with the pope in Rome. Although they are distinct theologically, liturgically, and historically from the Latin Church, they are all in full communion with it and with each other. Eastern Catholics are a minority within the Catholic Church; of the 1.3 billion Catholics in communion with the pope, approximately 18 million are members of the eastern churches. The largest numbers of Eastern Catholics are found in Eastern Europe, Eastern Africa, the Middle East, and India. As of 2022, the Syro-Malabar Church is the largest Eastern Catholic Church, followed by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[2]

With the exception of the Maronite Church, the Eastern Catholic Churches are groups that, at different points in the past, used to belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox churches, or the Church of the East; these churches underwent various schisms through history. Eastern Catholic Churches that were formerly part of other communions have been points of controversy in ecumenical relations with the Eastern Orthodox and other non-Catholic churches. The five historic liturgical traditions of Eastern Christianity, namely the Alexandrian Rite, the Armenian Rite, the Byzantine Rite, the East Syriac Rite, and the West Syriac Rite, are all represented within Eastern Catholic liturgy.[3] On occasion, this leads to a conflation of the liturgical word "rite" and the institutional word "church".[4] Some Eastern Catholic jurisdictions admit members of churches not in communion with Rome to the Eucharist and the other sacraments.[b]

Full communion with the bishop of Rome constitutes mutual sacramental sharing between the Eastern Catholic Churches and the Latin Church and the recognition and acceptance of papal supremacy and infallibility.[6][7] Provisions within the 1983 Latin canon law and the 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches govern the relationship between the Eastern and Latin churches. Historically, pressure to conform to the norms of the Western Christianity practiced by the majority Latin Church led to a degree of encroachment (Latinization) on some of the Eastern Catholic traditions. The Second Vatican Council document, Orientalium Ecclesiarum, built on previous reforms to reaffirm the right of Eastern Catholics to maintain their distinct practices.[8]

The 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches was the first codified body of canon law governing the Eastern Catholic Churches collectively,[9] although each church also has its own internal canons and laws on top of this. Members of Eastern Catholic churches are obliged to follow the norms of their particular church regarding celebration of church feasts, marriage, and other customs. Notable distinct norms include many Eastern Catholic Churches regularly allowing the ordination of married men to the priesthood (although not as bishops to the episcopacy), in contrast to the stricter clerical celibacy of the Latin Church. Both Latin and Eastern Catholics may freely attend a Catholic liturgy celebrated in any rite.[10]

Terminology

[edit]Although Eastern Catholics are in full communion with the pope and members of the worldwide Catholic Church,[c][d] they are not members of the Latin Church, which uses the Latin liturgical rites, among which the Roman Rite is the most widespread.[e] The Eastern Catholic churches are instead distinct particular churches sui iuris (autonomous), although they maintain full and equal, mutual sacramental exchange with members of the Latin Church.

Rite or church

[edit]There are different meanings of the word rite. Apart from its reference to the liturgical patrimony of a particular church, the word has been and is still sometimes, even if rarely, officially used of the particular church itself. Thus the term Latin rite can refer either to the Latin Church or to one or more of the Latin liturgical rites, which include the Roman Rite, Ambrosian Rite, Mozarabic Rite, and others.[citation needed]

In the 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches (CCEO),[14][15] the terms autonomous Church and rite are thus defined:

A group of Christian faithful linked in accordance with the law by a hierarchy and expressly or tacitly recognized by the supreme authority of the Church as autonomous is in this Code called an autonomous Church (canon 27).[16]

- A rite is the liturgical, theological, spiritual and disciplinary patrimony, culture and circumstances of history of a distinct people, by which its own manner of living the faith is manifested in each autonomous [sui iuris] Church.

- The rites treated in CCEO, unless otherwise stated, are those that arise from the Alexandrian, Antiochene, Armenian, Chaldean and Constantinopolitan traditions" (canon 28)[17] (not just a liturgical heritage, but also a theological, spiritual and disciplinary heritage characteristic of peoples' culture and the circumstances of their history).

When speaking of Eastern Catholic Churches, the Latin Church's 1983 Code of Canon Law (1983 CIC) uses the terms "ritual Church" or "ritual Church sui iuris" (canons 111 and 112), and also speaks of "a subject of an Eastern rite" (canon 1015 §2), "Ordinaries of another rite" (canon 450 §1), "the faithful of a specific rite" (canon 476), etc. The Second Vatican Council spoke of Eastern Catholic Churches as "particular Churches or rites".[18]: n. 2

In 1999, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops stated: "We have been accustomed to speaking of the Latin (Roman or Western) Rite or the Eastern Rites to designate these different Churches. However, the Church's contemporary legislation as contained in the Code of Canon Law and the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches makes it clear that we ought to speak, not of rites, but of Churches. Canon 112 of the Code of Canon Law uses the phrase 'autonomous ritual Churches' to designate the various Churches."[19] And a writer in a periodical of January 2006 declared: "The Eastern Churches are still mistakenly called 'Eastern-Rite' Churches, a reference to their various liturgical histories. They are most properly called Eastern Churches, or Eastern Catholic Churches."[20] However, the term "rite" continues to be used. The 1983 CIC forbids a Latin bishop to ordain, without permission of the Holy See, a subject of his who is "of an Eastern rite" (not "who uses an Eastern rite", the faculty for which is sometimes granted to Latin clergy).[21]

Uniate

[edit]The term Uniat or Uniate has been applied to Eastern Catholic churches and individual members whose church hierarchies were previously part of Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox churches. The term is sometimes considered derogatory by such people,[22][23] though it was used by some Latin and Eastern Catholics prior to the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965.[f] Official Catholic documents no longer use the term due to its perceived negative overtones.[26]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Eastern Catholic Churches have their origins in the Middle East, North Africa, East Africa, Eastern Europe and South India. However, since the 19th century, diaspora has spread to Western Europe, the Americas and Oceania in part because of persecution, where eparchies have been established to serve adherents alongside those of Latin Church dioceses. Latin Catholics in the Middle East, on the other hand, are traditionally cared for by the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem.[27]

The communion between Christian churches has been broken over matters of faith, whereby each side accused the other of heresy or departure from the true faith (orthodoxy). Communion has been broken also because of disagreement about questions of authority or the legitimacy of the election of a particular bishop. In these latter cases, each side accused the other of schism, but not of heresy.

The following ecumenical councils are major breaches of communion:

Council of Ephesus (AD 431)

[edit]In 431, the churches that accepted the teaching of the Council of Ephesus (which condemned the views of Nestorius) were classified as heretics by those who rejected the council's statements. The Church of the East, which was mainly under the Sassanid Empire, never accepted the council's views. It later experienced a period of great expansion in Asia before collapsing after the Mongol invasion of the Middle East in the 14th century.[citation needed]

Monuments of their presence still exist in China. Now they are relatively few in number and have divided into three churches: the Chaldean Catholic Church—an Eastern Catholic church in full communion with Rome—and two Assyrian churches which are not in communion with either Rome or each other. The Chaldean Catholic Church is the largest of the three. The groups of Assyrians who did not reunify with Rome remained and are known as the Assyrian Church of the East, which experienced an internal schism in 1968 which led to the creation of the Ancient Church of the East.[citation needed]

The Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara churches are the two Eastern Catholic descendants of the Church of the East in the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed]

Council of Chalcedon (AD 451)

[edit]In 451, those who accepted the Council of Chalcedon similarly classified those who rejected it as Monophysite heretics. The Churches that refused to accept the Council considered instead that it was they who were orthodox; they rejected the description Monophysite (meaning only-nature) preferring instead Miaphysite (meaning one-nature). The difference in terms may appear subtle, but it is theologically very important. "Monophysite" implies a single divine nature alone with no real human nature—a heretical belief according to Chalcedonian Christianity—whereas "Miaphysite" can be understood to mean one nature as God, existing in the person of Jesus who is both human and divine—an idea more easily reconciled to Chalcedonian doctrine. They are often called, in English, Oriental Orthodox Churches, to distinguish them from the Eastern Orthodox Church.[citation needed]

This distinction, by which the words oriental and eastern that in themselves have exactly the same meaning but are used as labels to describe two different realities, is impossible to translate in most other languages, and is not universally accepted even in English. These churches are also referred to as pre-Chalcedonian or now more rarely as non-Chalcedonian or anti-Chalcedonian. In languages other than English other means are used to distinguish the two families of churches. Some reserve the term "Orthodox" for those that are here called "Eastern Orthodox" churches, but members of what is called "Oriental Orthodox" Churches consider this illicit.[citation needed]

East–West Schism (1054)

[edit]The East–West Schism came about in the context of cultural differences between the Greek-speaking East and Latin-speaking West, and of rivalry between the churches in Rome—which claimed a primacy not merely of honour but also of authority—and in Constantinople, which claimed parity with Rome.[28] The rivalry and lack of comprehension gave rise to controversies, some of which appear already in the acts of the Quinisext Council of 692. At the Council of Florence (1431–1445), these controversies about Western theological elaborations and usages were identified as, chiefly, the insertion of "Filioque" into the Nicene Creed, the use of unleavened bread for the Eucharist, purgatory, and the authority of the pope.[g]

The schism is generally considered to have started in 1054, when the Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael I Cerularius, and the Papal Legate, Humbert of Silva Candida, issued mutual excommunications; in 1965, these excommunications were revoked by both Rome and Constantinople. In spite of that event, for many years both churches continued to maintain friendly relations and seemed to be unaware of any formal or final rupture.[30]

However, estrangement continued. In 1190, Eastern Orthodox theologian Theodore Balsamon, who was patriarch of Antioch, wrote that "no Latin should be given Communion unless he first declares that he will abstain from the doctrines and customs that separate him from us".[31]

Later in 1204, Constantinople was sacked by the Catholic armies of the Fourth Crusade, whereas two decades previously the Massacre of the Latins (i.e., Catholics) had occurred in Constantinople in 1182. Thus, by the 12th–13th centuries, the two sides had become openly hostile, each considering that the other no longer belonged to the church that was orthodox and catholic. Over time, it became customary to refer to the Eastern side as the Orthodox Church and the Western as the Catholic Church, without either side thereby renouncing its claim of being the truly orthodox or the truly catholic church.[citation needed]

Attempts at restoring communion

[edit]

Parties within many non-Latin churches repeatedly sought to organize efforts to restore communion. In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focused on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches.[32] Several eastern churches associated themselves with Rome, forming Eastern Catholic churches. The See of Rome accepted them without requiring that they adopt the customs of the Latin Church, so that they all have their own "liturgical, theological, spiritual and disciplinary heritage, differentiated by peoples' culture and historical circumstances, that finds expression in each sui iuris Church's own way of living the faith".[33]

Emergence of the churches

[edit]

Most Eastern Catholic churches arose when a group within an ancient church in disagreement with the See of Rome returned to full communion with that see. The following churches have been in communion with the Bishop of Rome for a large part of their history:

- The Maronite Church, which has no counterpart in Byzantine, nor Oriental, Orthodoxy. The Maronite Church has historical connections to the Monothelite controversy in the 7th century. It re-affirmed unity with the Holy See in 1154 during the Crusades.[34]

- The Maronite Church has historically been treated as never having fully schismed with the Holy See, despite a dispute over Christological doctrine that concluded in 1154; most of the other Eastern Catholic churches came into being from the 16th century onwards.[34]: 165–167 However, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, the Syro-Malabar Church and the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church also claim perpetual communion.

- The Albanian Greek Catholic Church and Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, which, unlike the Maronite Church, use the same liturgical rite as the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- The former Melkite Church considered itself in dual communion with Rome and Constantinople until an exclusively Orthodox body was formed in the 18th century, leaving a remainder unified exclusively with Rome as the Melkite Greek Catholic Church.

- The Oriental Orthodox Armenian Apostolic Church had included a long-standing minority that accepted Roman primacy until the Armenian Catholic Church was officially established in the 18th century.

The canon law shared by all Eastern Catholic churches, CCEO, was codified in 1990. The dicastery that works with the Eastern Catholic churches is the Dicastery for the Eastern Churches, which by law includes as members all Eastern Catholic patriarchs and major archbishops.

The largest six churches based on membership are, in order, the Syro-Malabar Church (East Syriac Rite), the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC; Byzantine Rite), the Maronite Church (West Syriac Rite), the Melkite Greek Catholic Church (Byzantine Rite), the Chaldean Catholic Church (East Syriac Rite), and the Armenian Catholic Church (Armenian Rite).[35] These six churches account for about 85% of the membership of the Eastern Catholic Churches.[36]

Orientalium dignitas

[edit]

On 30 November 1894, Pope Leo XIII issued the apostolic constitution Orientalium dignitas, in which he stated:

The Churches of the East are worthy of the glory and reverence that they hold throughout the whole of Christendom in virtue of those extremely ancient, singular memorials that they have bequeathed to us. For it was in that part of the world that the first actions for the redemption of the human race began, in accord with the all-kind plan of God. They swiftly gave forth their yield: there flowered in first blush the glories of preaching the True Faith to the nations, of martyrdom, and of holiness. They gave us the first joys of the fruits of salvation. From them has come a wondrously grand and powerful flood of benefits upon the other peoples of the world, no matter how far-flung. When blessed Peter, the Prince of the Apostles, intended to cast down the manifold wickedness of error and vice, in accord with the will of Heaven, he brought the light of divine Truth, the Gospel of peace, freedom in Christ to the metropolis of the Gentiles.[37]

Adrian Fortescue wrote that Leo XIII "begins by explaining again that the ancient Eastern rites are a witness to the Apostolicity of the Catholic Church, that their diversity, consistent with unity of the faith, is itself a witness to the unity of the Church, that they add to her dignity and honour. He says that the Catholic Church does not possess one rite only, but that she embraces all the ancient rites of Christendom; her unity consists not in a mechanical uniformity of all her parts, but on the contrary, in their variety, according in one principle and vivified by it."[38]

Leo XIII declared still in force Pope Benedict XIV's encyclical Demandatam, addressed to the Patriarch and the Bishops of the Melkite Catholic Church, in which Benedict XIV forbade Latin Church clergy to induce Melkite Catholics to transfer to the Roman Rite, and he broadened this prohibition to cover all Eastern Catholics, declaring: "Any Latin rite missionary, whether of the secular or religious clergy, who induces with his advice or assistance any Eastern rite faithful to transfer to the Latin rite, will be deposed and excluded from his benefice in addition to the ipso facto suspension a divinis and other punishments that he will incur as imposed in the aforesaid Constitution Demandatam."[37]

Second Vatican Council

[edit]

There had been confusion on the part of Western clergy about the legitimate presence of Eastern Catholic Churches in countries seen as belonging to the West, despite firm and repeated papal confirmation of these churches' universal character. The Second Vatican Council brought the reform impulse to visible fruition. Several documents, from both during and after the Second Vatican Council, have led to significant reform and development within Eastern Catholic Churches.[39][40]

Orientalium Ecclesiarum

[edit]

The Second Vatican Council directed, in Orientalium Ecclesiarum, that the traditions of Eastern Catholic Churches should be maintained. It declared that "it is the mind of the Catholic Church that each individual Church or Rite should retain its traditions whole and entire and likewise that it should adapt its way of life to the different needs of time and place" (n. 2), and that they should all "preserve their legitimate liturgical rite and their established way of life, and ... these may not be altered except to obtain for themselves an organic improvement" (n. 6; cf. n. 22).[18]

It confirmed and approved the ancient discipline of the sacraments existing in the Eastern churches, and the ritual practices connected with their celebration and administration, and declared its ardent desire that this should be re-established if circumstances warranted (n. 12). It applied this in particular to administration of sacrament of Confirmation by priests (n. 13). It expressed the wish that, where the permanent diaconate (ordination as deacons of men who are not intended afterwards to become priests) had fallen into disuse, it should be restored (n. 17).

Paragraphs 7–11 are devoted to the powers of the patriarchs and major archbishops of the Eastern Churches, whose rights and privileges, it says, should be re-established in accordance with the ancient tradition of each of the churches and the decrees of the ecumenical councils, adapted somewhat to modern conditions. Where there is a need, new patriarchates should be established either by an ecumenical council or by the Bishop of Rome.

Lumen gentium

[edit]The Second Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen gentium, deals with Eastern Catholic Churches in paragraph 23, stating:

By divine Providence it has come about that various churches, established in various places by the apostles and their successors, have in the course of time coalesced into several groups, organically united, which, preserving the unity of faith and the unique divine constitution of the universal Church, enjoy their own discipline, their own liturgical usage, and their own theological and spiritual heritage. Some of these churches, notably the ancient patriarchal churches, as parent-stocks of the Faith, so to speak, have begotten others as daughter churches, with which they are connected down to our own time by a close bond of charity in their sacramental life and in their mutual respect for their rights and duties. This variety of local churches with one common aspiration is splendid evidence of the catholicity of the undivided Church. In like manner the Episcopal bodies of today are in a position to render a manifold and fruitful assistance, so that this collegiate feeling may be put into practical application.[41]

Unitatis redintegratio

[edit]The 1964 decree Unitatis redintegratio deals with Eastern Catholic Churches in paragraphs 14–17.[42]

Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches

[edit]The First Vatican Council discussed the need for a common code for the Eastern churches, but no concrete action was taken. Only after the benefits of the Latin Church's 1917 Code of Canon Law were appreciated was a serious effort made to codify the Eastern Catholic Churches' canon laws.[43]: 27 This came to fruition with the promulgation of the 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, which took effect in 1991. It is a framework document that contains canons that are a consequence of the common patrimony of the churches of the East: each individual sui iuris church also has its own canons, its own particular law, layered on top of this code.

Joint International Commission

[edit]In 1993 the Joint International Commission for Theological Dialogue Between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church submitted the document Uniatism, method of union of the past, and the present search for full communion, also known as the Balamand declaration, "to the authorities of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches for approval and application,"[44] which stated that initiatives that "led to the union of certain communities with the See of Rome and brought with them, as a consequence, the breaking of communion with their Mother Churches of the East ... took place not without the interference of extra-ecclesial interests".[44]: n. 8

Likewise the commission acknowledged that "certain civil authorities [who] made attempts" to force Eastern Catholics to return to the Orthodox Church used "unacceptable means".[44]: n. 11 The missionary outlook and proselytism that accompanied the Unia[44]: n. 10 was judged incompatible with the rediscovery by the Catholic and Orthodox churches of each other as sister churches.[44]: n. 12 Thus the commission concluded that the "missionary apostolate, ... which has been called 'uniatism', can no longer be accepted either as a method to be followed or as a model of the unity our Churches are seeking."[44]: n. 12

At the same time, the commission stated:

- that Eastern Catholic Churches, being part of the Catholic Communion, have the right to exist and to act in response to the spiritual needs of their faithful;[44]: n. 3

- that Oriental Catholic Churches, which desired to re-establish full communion with the See of Rome and have remained faithful to it, have the rights and obligations connected with this communion.[44]: n. 16

These principles were repeated in the 2016 Joint Declaration of Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill, which stated that 'It is today clear that the past method of “uniatism”, understood as the union of one community to the other, separating it from its Church, is not the way to re-establish unity. Nonetheless, the ecclesial communities which emerged in these historical circumstances have the right to exist and to undertake all that is necessary to meet the spiritual needs of their faithful, while seeking to live in peace with their neighbours. Orthodox and Greek Catholics are in need of reconciliation and of mutually acceptable forms of co–existence.'[45]

Liturgical prescriptions

[edit]

The 1996 Instruction for Applying the Liturgical Prescriptions of the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches brought together, in one place, the developments that took place in previous texts,[46] and is "an expository expansion based upon the canons, with constant emphasis upon the preservation of Eastern liturgical traditions and a return to those usages whenever possible—certainly in preference to the usages of the Latin Church, however much some principles and norms of the conciliar constitution on the Roman rite, "in the very nature of things, affect other rites as well."[43]: 998 The Instruction states:

The liturgical laws valid for all the Eastern Churches are important because they provide the general orientation. However, being distributed among various texts, they risk remaining ignored, poorly coordinated and poorly interpreted. It seemed opportune, therefore, to gather them in a systematic whole, completing them with further clarification: thus, the intent of the Instruction, presented to the Eastern Churches which are in full communion with the Apostolic See, is to help them fully realize their own identity. The authoritative general directive of this Instruction, formulated to be implemented in Eastern celebrations and liturgical life, articulates itself in propositions of a juridical-pastoral nature, constantly taking initiative from a theological perspective.[46]: n. 5

Past interventions by the Holy See, the Instruction said, were in some ways defective and needed revision, but often served also as a safeguard against aggressive initiatives.

These interventions felt the effects of the mentality and convictions of the times, according to which a certain subordination of the non-Latin liturgies was perceived toward the Latin-Rite liturgy which was considered "ritus praestantior".[h] This attitude may have led to interventions in the Eastern liturgical texts which today, in light of theological studies and progress, have need of revision, in the sense of a return to ancestral traditions. The work of the commissions, nevertheless, availing themselves of the best experts of the times, succeeded in safeguarding a major part of the Eastern heritage, often defending it against aggressive initiatives and publishing precious editions of liturgical texts for numerous Eastern Churches. Today, particularly after the solemn declarations of the Apostolic Letter Orientalium dignitas by Leo XIII, after the creation of the still active special Commission for the liturgy within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches in 1931, and above all after the Second Vatican Council and the Apostolic Letter Orientale Lumen by John Paul II, respect for the Eastern liturgies is an indisputable attitude and the Apostolic See can offer a more complete service to the Churches.[46]: n. 24

Organisation

[edit] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Papal supreme authority

[edit]

Under the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, the pope has supreme, full, immediate and universal ordinary authority in the whole Catholic Church, which he can always freely exercise, including the Eastern Catholic churches.[47][i]

Eastern patriarchs and major archbishops

[edit]

The Catholic patriarchs and major archbishops derive their titles from the sees of Alexandria (Coptic), Antioch (Syriac, Melkite, Maronite), Baghdad (Chaldean), Cilicia (Armenian), Kyiv-Halych (Ukrainian), Ernakulam-Angamaly (Syro-Malabar), Trivandrum (Syro-Malankara), and Făgăraş-Alba Iulia (Romanian). The Eastern Catholic churches are governed in accordance with Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches and their particular laws.[49]

Within their proper sui iuris churches there is no difference between patriarchs and major archbishops. However, differences exist in the order of precedence (i.e. patriarchs take precedence over major archbishops) and in the mode of accession: The election of a major archbishop has to be confirmed by the pope before he may take office.[50] No papal confirmation is needed for newly elected patriarchs before they take office. They are just required to request as soon as possible that the pope grant them full ecclesiastical communion.[51][j]

Variants of organizational structure

[edit]There are significant differences between various Eastern Catholic churches, regarding their present organizational structure. Major Eastern Catholic churches, that are headed by their patriarchs, major archbishops or metropolitans, have fully developed structure and functioning internal autonomy based on the existence of ecclesiastical provinces. On the other hand, minor Eastern Catholic churches often have only one or two hierarchs (in the form of eparchs, apostolic exarchs, or apostolic visitors) and only the most basic forms of internal organization if any, like the Belarusian Greek Catholic Church or the Russian Greek Catholic Church.[53] Individual eparchies of some Eastern Catholic churches may be suffragan to Latin metropolitans. For example, the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Križevci is suffragan to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb.[54] Also, some minor Eastern Catholic churches have Latin prelates. For example, the Macedonian Greek Catholic Church is organized as a single Eparchy of Strumica-Skopje, whose present ordinary is the Roman Catholic bishop of Skopje.[55] The organization of the Albanian Greek Catholic Church is unique in that it consists of an "Apostolic Administration".[56]

Juridical status

[edit]Although every diocese in the Catholic Church is considered a particular church, the word is not applied in the same sense as to the 24 sui iuris particular churches: the Latin Church and the 23 Eastern Catholic Churches.[citation needed]

Canonically, each Eastern Catholic Church is sui iuris or autonomous with respect to other Catholic churches, whether Latin or Eastern, though all accept the spiritual and juridical supreme authority of the pope. Thus a Maronite Catholic is normally directly subject only to a Maronite bishop. However, if members of a particular church are so few that no hierarchy of their own has been established, their spiritual care is entrusted to a bishop of another ritual church. For instance, members of the Latin Church in Eritrea are under the care of the Eastern rite Eritrean Catholic Church, whereas the other way around may be the case in other parts of the world.[citation needed]

Theologically, all the particular churches can be viewed as "sister churches".[57] According to the Second Vatican Council these Eastern Catholic churches, along with the larger Latin Church, share "equal dignity, so that none of them is superior to the others as regards rite, and they enjoy the same rights and are under the same obligations, also in respect of preaching the Gospel to the whole world (cf. Mark 16:15) under the guidance of the Roman Pontiff."[18]: n. 3

The Eastern Catholic churches are in full communion with the whole Catholic Church. While they accept the canonical authority of the Holy See of Rome, they retain their distinctive liturgical rites, laws, customs and traditional devotions, and have their own theological emphases. Terminology may vary: for instance, diocese and eparchy, vicar general and protosyncellus, confirmation and chrismation are respectively Western and Eastern terms for the same realities. The mysteries (sacraments) of baptism and chrismation are generally administered, according to the ancient tradition of the church, one immediately after the other. Infants who are baptized and chrismated are also given the Eucharist.[58]

The Eastern Catholic churches are represented in the Holy See and the Roman Curia through the Dicastery for the Eastern Churches, which is "made up of a Cardinal Prefect (who directs and represents it with the help of a Secretary) and 27 cardinals, one archbishop and 4 bishops, designated by the pope ad quinquennium (for a five-year period). Members by right are the Patriarchs and the Major Archbishops of the Oriental Churches and the President of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of Unity among Christians."[59]

Bi-ritual faculties

[edit]

While "clerics and members of institutes of consecrated life are bound to observe their own rite faithfully",[60] priests are occasionally given permission to celebrate the liturgy of a rite other than the priest's own rite, by what is known as a grant of "biritual faculties". The reason for this permission is usually the service of Catholics who have no priest of their own rite. Thus priests of the Syro-Malabar Church working as missionaries in areas of India in which there are no structures of their own Church, are authorized to use the Roman Rite in those areas, and Latin priests are, after due preparation, given permission to use an Eastern rite for the service of members of an Eastern Catholic Church living in a country in which there are no priests of their own particular Church. Popes are permitted to celebrate a Mass or Divine Liturgy of any rite in testament to the Catholic Church's universal nature. John Paul II celebrated the Divine Liturgy in Ukraine during his pontificate.

For a just cause, and with the permission of the local bishop, priests of different autonomous ritual churches may concelebrate; however, the rite of the principal celebrant is used whilst each priest wears the vestments of his own rite.[61] No indult of bi-ritualism is required for this.

Biritual faculties may concern not only clergy but also religious, enabling them to become members of an institute of an autonomous Church other than their own.[62]

Clerical celibacy

[edit]

Eastern and Western Christian churches have different traditions concerning clerical celibacy and the resulting controversies have played a role in the relationship between the two groups in some Western countries.

In general, Eastern Catholic Churches have always allowed ordination of married men as priests and deacons. Within the lands of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the third largest Eastern Catholic Church, where 90% of the diocesan priests in Ukraine are married,[63] priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a tightly knit hereditary caste.[64][contentious label]

Most Eastern Churches distinguish between monastic and non-monastic clergy. Monastics do not necessarily live in monasteries, but have spent at least part of their period of training in such a context. Their monastic vows include a vow of celibate chastity.

Bishops are normally selected from the monastic clergy, and in most Eastern Catholic Churches a large percentage of priests and deacons also are celibate, while a large portion of the parish priests are married, having taken a wife when they were still laymen.[64] If someone preparing for the diaconate or priesthood wishes to marry, this must happen before ordination.

In territories where Eastern traditions prevail, married clergy caused little controversy, but aroused opposition inside traditionally Latin Church territories to which Eastern Catholics migrated;[citation needed] this was particularly so in the United States.[dubious – discuss] In response to requests from the Latin bishops of those countries, the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith set out rules in an 1890 letter to François-Marie-Benjamin Richard, archbishop of Paris,[65] which the Congregation applied on 1 May 1897 to the United States, stating that only celibates or widowed priests coming without their children should be permitted in the United States.[66][full citation needed]

This celibacy mandate for Eastern Catholic priests in the United States was restated with special reference to Ruthenians by the 1 March 1929 decree Cum data fuerit, which was renewed for a further ten years in 1939. Dissatisfaction by many Ruthenian Catholics in the United States gave rise to the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese.[67] The mandate, which applied in some other countries also,[which?] was removed by a decree of June 2014.[68]

While most Eastern Catholic Churches admit married men to ordination as priests, some have adopted mandatory clerical celibacy, as in the Latin Church. These include the India-based Syro-Malankara Catholic Church and Syro-Malabar Catholic Church,[69][70] and the Coptic Catholic Church.[63]

In 2014, Pope Francis approved new norms for married clergy within Eastern Catholic Churches through CCEO canon 758 § 3.[citation needed] The new norms abrogated previous norms and now allow those Eastern Catholic Churches with married clergy to ordain married men inside traditionally Latin territories and to grant faculties inside traditionally Latin territories to married Eastern Catholic clergy previously ordained elsewhere.[71] This latter change will allow married Eastern Catholic priests to follow their faithful to whatever country they may immigrate to, addressing an issue which has arisen with the migration of Christians from Eastern Europe and the Middle East in recent decades.[72][as of?]

List of Eastern Catholic churches

[edit]

The Holy See's Annuario Pontificio gives the following list of Eastern Catholic churches with the principal episcopal see of each and the countries (or larger political areas) where they have ecclesiastical jurisdiction, to which are here added the date of union or foundation in parentheses and the membership in brackets. The total membership for all Eastern Catholic churches is at least 18,047,000 people.

- ^ Except as otherwise indicated for the Albanian, Belarusian, and Russian Churches.

- ^ Historically, in Georgia, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Eastern Catholicism thrived as a unique branch of the greater Catholic ecumene, when in 1861, ex-Mekhistarist priest Peter Kharischirashvili founded the Servites of the Immaculate Conception in Istanbul. However, the Stalinist purges in the 1920s and 1930s essentially eradicated the eclassiastical independence of the community, and the remaining members lived only until the late 1950s. Today, Catholics in Georgia adhere to the Latin and Armenian rites instead of the Byzantine one, composed mostly of ethnic Georgians and Armenians.

- ^ a b The Greek Catholic Church of Croatia and Serbia comprises two jurisdictions: Greek Catholic Eparchy of Križevci covering Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Greek Catholic Eparchy of Ruski Krstur covering Serbia. The Eparchy of Križevci is in foreign province, and the Eparchy of Ruski Krstur is immediately subject to the Holy See.

- ^ a b The Greek Byzantine Catholic Church comprises two independent apostolic exarchates covering Greece and Turkey respectively, each immediately subject to the Holy See.

- ^ a b The Italo-Albanian Greek Catholic Church comprises two independent eparchies (based in Lungro and Piana degli Albanesi) and one territorial abbacy (based in Grottaferrata), each immediately subject to the Holy See.

- ^ Kiro Stojanov serves as bishop of the Macedonian Eparchy of the Assumption in addition to his primary duties as the Latin Church bishop of Skopje, and so GCatholic only counts him as a Latin Church bishop.

- ^ a b The Russian Greek Catholic Church comprises two apostolic exarchates (one for Russia and one for China), each immediately subject to the Holy See and each vacant for decades. Bishop Joseph Werth of Novosibirsk has been appointed by the Holy See as ordinary to the Eastern Catholic faithful in Russia, although not as exarch of the dormant apostolic exarchate and without the creation of a formal ordinariate.

- ^ The Ruthenian Catholic Church does not have a unified structure. It includes a Metropolia based in Pittsburgh, which covers the entire United States, but also an eparchy in Ukraine and an apostolic exarchate in the Czech Republic, both of which are directly subject to the Holy See.

- ^ Five of the ordinariates for Eastern Catholics are multi-ritual, encompassing the faithful of all Eastern Catholicism within their territory not otherwise subject to a local ordinary of their own rite. The sixth is exclusively Byzantine, but covers all Byzantine Catholics in Austria, no matter which particular Byzantine Church they belong to.

- ^ The six ordinariates are based in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Vienna (Austria), Belo Horizonte (Brazil), Paris (France), Warsaw (Poland), and Madrid (Spain).

- ^ Technically, each of these ordinariates has an ordinary who is a bishop, but all of the bishops are Latin bishops whose primary assignment is to a Latin see.

Persecution

[edit]Eastern Europe

[edit]A study by Methodios Stadnik states: "The Georgian Byzantine Catholic Exarch, Fr. Shio Batmanishviii [sic], and two Georgian Catholic priests of the Latin Church were executed by the Soviet authorities in 1937 after having been held in captivity in Solovki prison and the northern gulags from 1923."[78] Christopher Zugger writes, in The Forgotten: "By 1936, the Byzantine Catholic Church of Georgia had two communities, served by a bishop and four priests, with 8,000 believers", and he identifies the bishop as Shio Batmalashvili.[79] Vasyl Ovsiyenko mentions, on the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union website, that "the Catholic administrator for Georgia Shio Batmalashvili" was one of those executed as "anti-Soviet elements" in 1937.[80]

Zugger calls Batmalashvili a bishop; Stadnik is ambiguous, calling him an exarch but giving him the title of Father; Ovsiyenko merely refers to him as "the Catholic administrator" without specifying whether he was a bishop or a priest and whether he was in charge of a Latin or a Byzantine jurisdiction.[citation needed]

If Batmalashvili was an exarch, and not instead a bishop connected with the Latin diocese of Tiraspol, which had its seat at Saratov on the Volga River, to which Georgian Catholics even of Byzantine rite belonged [81] this would mean that a Georgian Byzantine-Rite Catholic Church existed, even if only as a local particular Church. However, since the establishment of a new hierarchical jurisdiction must be published in Acta Apostolicae Sedis, and no mention of the setting up of such a jurisdiction for Byzantine Georgian Catholics exists in that official gazette of the Holy See, the claim appears to be unfounded.

The 1930s editions of Annuario Pontificio do not mention Batmalashvili. If indeed he was a bishop, he may then have been one of those secretly ordained for the service of the Church in the Soviet Union by French Jesuit Bishop Michel d'Herbigny, who was president of the Pontifical Commission for Russia from 1925 to 1934. In the circumstances of that time, the Holy See would have been incapable of setting up a new Byzantine exarchate within the Soviet Union, since Greek Catholics in the Soviet Union were being forced to join the Russian Orthodox Church.[citation needed]

Batmalashvili's name is not among those given in as the four "underground" apostolic administrators (only one of whom appears to have been a bishop) for the four sections into which the diocese of Tiraspol was divided after the resignation in 1930 of its already exiled last bishop, Josef Alois Kessler.[82] This source gives Father Stefan Demurow as apostolic administrator of "Tbilisi and Georgia" and says he was executed in 1938. Other sources associate Demurow with Azerbaijan and say that, rather than being executed, he died in a Siberian Gulag.[83]

Until 1994, the United States annual publication Catholic Almanac listed "Georgian" among the Greek Catholic churches.[84] Until corrected in 1995, it appears to have been also making a mistake about the Czech Greek Catholics.

There was a short-lived Greek Catholic movement among the ethnic Estonians in the Orthodox Church in Estonia during the interwar period of the 20th century, consisting of two to three parishes, not raised to the level of a local particular church with its own head. This group was liquidated by the Soviet regime and is now extinct.[citation needed]

Muslim world

[edit]United States

[edit]While not subject to the kind of physical dangers or persecution from government authorities encountered in Eastern Europe or the Middle East, adherents of Eastern Catholic Churches in United States, most of whom were relatively new immigrants from Eastern Europe, encountered difficulties due to hostility from the Latin Church clergy who dominated the Catholic hierarchy in United States who found them alien. In particular, immigration of Eastern Catholic priests who were married, common in their churches but extremely rare in Latin churches, was forbidden or severely limited and some Latin Church bishops actively interfered with the pastoral work of those who did arrive. Some bishops sought to forbid all non-Latin Catholic priests from coming to United States at all. Many Eastern Catholic immigrants to United States were thus either assimilated into the Latin Church or joined the Eastern Orthodox Church. One former Eastern Catholic priest, Alexis Toth, left the Catholic Church following criticism and sanctions from Latin authorities including John Ireland, the Bishop of Saint Paul, and joining the Orthodox Church. Toth has been canonized as an Eastern Orthodox saint for having led as many as 20,000 disaffected former Eastern Catholics to the Orthodox Church, particularly the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In some historical cases, they are referred to as Uniates.

- ^ "Catholic ministers licitly administer the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and anointing of the sick to members of Eastern churches which do not have full communion with the Catholic Church if they seek such on their own accord and are properly disposed. This is also valid for members of other Churches which in the judgment of the Apostolic See have the same beliefs in regard to the sacraments as these Eastern Churches"[5]

- ^ "The Catholic Church is also called the Roman Church to emphasize that the centre of unity, which is essential for the Universal Church, is the Roman See"[11]

- ^ Examples of the use of "Roman Catholic Church" by popes, even when not addressing members of non-Catholic churches, are the encyclicals Divini illius Magistri and Humani generis, and Pope John Paul II's address at the 26 June 1985 general audience, in which he treated "Roman Catholic Church" as synonymous with "Catholic Church".[12] The term "Roman Catholic Church" is repeatedly used to refer to the whole Church in communion with the see of Rome, including Eastern Catholics, in official documents concerning dialogue between the Church as a whole (not just the Western part) and groups outside her fold. Examples of such documents can be found at the links on the Vatican website under the heading Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. The Holy See presently does not use "Roman Catholic Church" to refer only to the Western or Latin Church. In the First Vatican Council's Dogmatic Constitution de fide catholica, the phrase the Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Church (Sancta catholica apostolica Romana ecclesia) also refers to something other than the Latin or Western Church.

- ^ Some Eastern Catholics who use the Byzantine liturgical rite and call themselves "Byzantine Catholics" deny that they are "Roman Catholics", using this word to mean either Catholics who use the Roman Rite or perhaps the whole Latin Church, including those parts that use the Ambrosian Rite or other non-Roman liturgical rites: "We're Byzantine rite, which is Catholic, but not Roman Catholic" [13]

- ^ The term was used by the Holy See, for example, Pope Benedict XIV in Ex quo primum.[24] The Catholic Encyclopedia consistently used the term Uniat to refer to Eastern Catholics, stating: "The 'Uniat Church' is therefore really synonymous with 'Eastern Churches united to Rome', and 'Uniats' is synonymous with 'Eastern Christians united with Rome'.[25]

- ^ "In the third sitting of the Council, Julian, after mutual congratulations, showed that the principal points of dispute between the Greeks and Latins were in the doctrine (a) on the procession of the Holy Ghost, (b) on azymes in the Eucharist, (c) on purgatory, and (d) on the Papal supremacy"[29]

- ^ Ritus praestantior means "preeminent rite" or "more excelling rite".

- ^ The full description is in CCEO canons 42 to 54.[48]

- ^ An example of the petition and the granting of ecclesiastical communion.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ "The beautiful witness of the Eastern Catholic Churches". Catholic Herald. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Annuario Orientale Cattolico - 2023 by Vartan Waldir Boghossian EXARMAL - Issuu". issuu.com. 2023-09-09. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Yurkus, Kevin (August 2005). "The Other Catholics: A Short Guide to the Eastern Catholic Churches". Archived from the original on 2019-08-25. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- ^ LaBanca, Nicholas (January 2019). "The Other Catholics: A Short Guide to the Eastern Catholic Churches-The Other 23 Catholic Churches and Why They Exist". Ascension Press. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

- ^ CCEO canon 671 §3; Archived November 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine cf. 1983 CIC canon 844 §3 Archived December 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Do Eastern Catholics Accept Papal Infallibility?". REASON & THEOLOGY. 2023-12-09. Retrieved 2025-08-25.

- ^ Guy | 11/07/2023, That Eastern Catholic. "What does the Eastern Catholic Church believe?". Catholic365. Retrieved 2025-08-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Parry, Ken; David Melling, eds. (1999). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23203-6.

- ^ "Master Page on Eastern Canon Law (1990)". www.canonlaw.info. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ^ Caridi, Cathy (April 5, 2018). "Becoming (Or at Least Marrying) an Eastern Catholic". Canon Law Made Easy.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: O'Brien, Thomas J., ed. (1901). "An Advanced Catechism of Catholic Faith and Practice: Based Upon the Third Plenary Council Catechism, for Use in the Higher Grades of Catholic Schools". An advanced catechism of Catholic faith and practice: based upon The Third Plenary Council Catechism. Akron, OH; Chicago, IL: D. H. McBride. n. 133. OCLC 669694820.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: O'Brien, Thomas J., ed. (1901). "An Advanced Catechism of Catholic Faith and Practice: Based Upon the Third Plenary Council Catechism, for Use in the Higher Grades of Catholic Schools". An advanced catechism of Catholic faith and practice: based upon The Third Plenary Council Catechism. Akron, OH; Chicago, IL: D. H. McBride. n. 133. OCLC 669694820.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (1985-06-26). [catechesis] (Speech). General audience (in Italian).

- ^ "Ukrainian church pastor honored".[dead link]

- ^ "Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ "Codex canonum Ecclesiarium orientalium". Intratext.com. 2007-05-04. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ CCEO canon 27

- ^ CCEO canon 28

- ^ a b c Catholic Church. Second Vatican Council; Pope Paul VI (1964-11-21). Orientalium Ecclesiarum. Vatican City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Catholic Church. National Council of Catholic Bishops. Committee on the relationship between Eastern and Latin Catholic Churches (1999). Eastern Catholics in the United States of America. Washington, DC: United States Catholic Conference. ISBN 978-1-57455-287-4.

- ^ Zagano, Phyllis (Jan 2006). "What all Catholics should know about Eastern Catholic Churches". americancatholic.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ 1983 CIC canon 1015 §2 Archived April 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine; see 1983 CIC canons 450 §1, and 476.

- ^ "The Word 'Uniate' ". oca.org. Syosset, NY: The Orthodox Church in America. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

The term commonly refers to those Orthodox Christians who left Orthodoxy and acknowledged the jurisdiction of the Pope of Rome while retaining the rites and practices observed by Orthodoxy. [...] The term 'uniate' is seen as negative by such individuals, who are more commonly referred to as Catholics of the Byzantine Rite, Greek Catholics, Eastern Rite Catholics, Melkite Catholics, or any number of other titles.

- ^ "The Catholic Eastern Churches". cnewa.org. New York: Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011.

It should be mentioned that in the past the Eastern Catholic churches were often referred to as 'Uniate' churches. Since the term is now considered derogatory, it is no longer used.

- ^ Pope Benedict XIV (1756-03-01). Ex quo primum (in Latin). Rome: Luxemburgi. n. 1. hdl:2027/ucm.5317972342.

sive, uti vocant, Unitos.

Translated in "On the Euchologion". ewtn.com. Irondale, AL: Eternal Word Television Network. - ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1909). "Greek Church". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1909). "Greek Church". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Siecienski, A. Edward (2019). Orthodox Christianity: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 108.

- ^ Bailey, Betty Jane & J. Marttin (November 12, 2010). Who Are the Christians in the Middle East?. William B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 90.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (Jan 1996). Halsall, Paul (ed.). "Caesaropapism?: Theodore Balsamon on the powers of the Patriarch of Constantinople". fordham.edu. Internet History Sourcebooks Project. Archived from the original on 2014-09-25. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Barnes, Patrick (ed.). "The Orthodox Response to the Latin Doctrine of Purgatory". orthodoxinfo.com. Patrick Barnes.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Ostroumov, Ivan N. (1861). "Opening of the council in Ferrara; private disputes on purgatory". In Neale, John M (ed.). The history of the Council of Florence. Translated by Vasiliĭ Popov. London: J. Masters. p. 47. OCLC 794347635.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Ostroumov, Ivan N. (1861). "Opening of the council in Ferrara; private disputes on purgatory". In Neale, John M (ed.). The history of the Council of Florence. Translated by Vasiliĭ Popov. London: J. Masters. p. 47. OCLC 794347635.

- ^ Anastos, Milton V. "The Normans and the schism of 1054". myriobiblos.gr. Constantinople and Rome. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Heresy and the Making of European Culture: Medieval and Modern Perspectives at Google Books p. 42

- ^ Geanakoplos, Deno John (1989). Constantinople and the West. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-11880-0.

- ^ CCEO canon 28 §1

- ^ a b c Donald Attwater (1937). Joseph Husslein (ed.). The Christian Churches of the East: Volume I: Churches in Communion With Rome. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company.

- ^ Roberson, Ronald. "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017" (PDF). cnewa.org. Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ^ Roberson, Ronald G. "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2016" (PDF). Eastern Catholic Churches Statistics. Catholic Near East Welfare Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ a b Pope Leo XIII (1894-11-30). "Orientalium dignitas". papalencyclicals.net. opening paragraph.

- ^ Fortescue, Adrian (2001) [First published 1923]. Smith, George D. (ed.). The Uniate Eastern Churches: the Byzantine rite in Italy, Sicily, Syria and Egypt. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-9715986-3-0.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Remedios, Matthew (22 December 2022). "Vatican II and Liturgical Reform in the Eastern Churches: The Paradox in the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church". Saeculum. 16 (1): 15–36. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Klesko, Robert (12 July 2023). "Are We on the Verge of an Eastern Catholic Moment?". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Catholic Church. Second Vatican Council; Pope Paul VI (1964-11-21). Lumen gentium. Vatican City. n. 23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Catholic Church. Second Vatican Council; Pope Paul VI (1964-11-21). Unitatis Redintegratio. Vatican City. nn. 14–17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Beal, John P; Coriden, James A; Green, Thomas J, eds. (2000). New commentary on the Code of Canon Law (study ed.). New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 0-8091-0502-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Joint international commission for the theological dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. Uniatism, method of union of the past, and the present search for full communion. Seventh plenary session of the joint international commission for theological dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. Balamand, Lebanon. June 17–24, 1993. Archived from the original on 2003-12-23.

- ^ "Joint Declaration of Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia". 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Congregation for the Eastern Churches (1996). Instruction for applying the liturgical prescriptions of the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches (PDF). Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 978-88-209-2232-0.

- ^ CCEO canon 43

- ^ CCEO canons 42–54

- ^ CCEO canon 1

- ^ CCEO canon 153

- ^ CCEO canon 76

- ^ "Exchange of letters between Benedict XVI and His Beatitude Antonios Naguib". Holy See Press Office. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- ^ David M. Cheney. "Apostolic Exarchate of Russia". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ David M. Cheney. "Diocese of Križevci". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ David M. Cheney. "Eparchy of Beata Maria Vergine Assunta in Strumica-Skopje". Catholic Hierarchy. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- ^ David M. Cheney. "Apostolic Administration of Southern Albania". Catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ Congregation for the doctrine of the faith (2000-06-30). Note on the expression 'sister Churches'. n. 11. Archived from the original on 2015-04-01.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church n. 1233

- ^ Congregation for the Oriental Churches (2003-03-20). "Profile". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ CCEO canon 40

- ^ CCEO canon 701. This English translation omits the word "optabiliter" of the original Latin text.

- ^ CCEO canons 451 and 517 §2

- ^ a b Galadza, Peter (2010). "Eastern Catholic Christianity". In Parry, Kenneth (ed.). The Blackwell companion to Eastern Christianity. Blackwell companions to religion. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- ^ a b Subtelny, Orest (2009). Ukraine: a history (4th ed.). Toronto [u.a.]: University of Toronto Press. pp. 214–219. ISBN 978-1-4426-9728-7.

- ^ Catholic Church. Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (1890-05-12). "Fragmentum epistolae S. C. de Propaganda Fide diei 12 Maii 1890 ad Archiep. Parisien, de auctoritate Patriarcharum orientalium extra proprias Dioeceses ..." (PDF). Acta Sanctae Sedis (in Latin). 24 (1890–1891): 390–391. OCLC 565282294.

- ^ "Collectanea". Collectanea (1966).

- ^ Barringer, Lawrence (1985). Good Victory. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 0-917651-13-8.

- ^ "Vatican lifts married priests ban in US, Canada, and Australia" in CathNews New Zealand, 21 November 2014

- ^ Thangalathil, Benedict Varghese Gregorios (1993-01-01). "An Oriental Church returns to unity choosing priestly celibacy". vatican.va.

- ^ Ziegler, Jeff (2011-05-09). "A Source of Hope". catholicworldreport.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-17.

- ^ Catholic Church. Congregatio pro Ecclesiis Orientalibus (2014-06-14). "Pontificia praecepta de clero uxorato orientali" (PDF). Acta Apostolicae Sedis (in Latin). 106 (6) (published 2014-06-06): 496–499. ISSN 0001-5199. Translated in "precepts about married eastern clergy" (PDF). Pontifical. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-19. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ^ "Vatican introduces new norms for Eastern rite married priests". vaticaninsider.lastampa.it. La Stampa. 2014-11-15. Archived from the original on 2014-12-19. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ^ "Rites of the Catholic Church". GCatholic.org. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- ^ "Erezione della Chiesa Metropolitana sui iuris eritrea e nomina del primo Metropolita". Holy See Press Office. January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Catholic Church (2012). Annuario Pontificio. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 978-88-209-8722-0.

- ^ "CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF THE SYROMALABAR CHURCH". Syro-Malabar Church Official website. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Tisserant, Eugene (1957). Hambye, E. R. (ed.). Eastern Christianity in India: A History of the Syro-Malabar Church from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Westminster: Newman Press. pp. 134–135.

- ^ Stadnik, Methodios (1999-01-21). "A concise history of the Georgian Byzantine Catholic Church". stmichaelruscath.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Zugger, Christopher L. (2001). "Secret agent and secret hierarchy". The forgotten: Catholics of the Soviet Union Empire from Lenin through Stalin. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8156-0679-6.

- ^ Ovsiyenko, Vasyl (2006-10-26). "In memory of the victims of the Solovky embarkation point". helsinki.org.ua. Kyiv: Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. Retrieved 2011-04-27.

- ^ Catholic Church. Congregatio pro Ecclesiis Orientalibus (1974). Oriente Cattolico : Cenni Storici e Statistiche (in Italian) (4th ed.). Vatican City. p. 194. OCLC 2905279.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Roman Catholic Regional Hierarchy". Archived from the original on 2004-06-01. Retrieved 2004-06-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) This tertiary source reuses information from other sources but does not name them. - ^ "Small Catholic community comes to life in former Communist country". fides.org. Vatican City: Agenzia Fides. 2005-09-10. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14.

- ^ "Georgian". Catholic Almanac.

Further reading

[edit]- Nedungatt, George, ed. (2002). A Guide to the Eastern Code: A Commentary on the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches. Rome: Oriental Institute Press. ISBN 9788872103364.

- Faris, John D., & Jobe Abbass, OFM Conv., eds. A Practical Commentary to the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, 2 vols. Montréal: Librairie Wilson & Lafleur, 2019.

External links

[edit]Eastern Catholic Churches

View on GrokipediaThe Eastern Catholic Churches are the 23 autonomous sui iuris particular churches of the Catholic Church that preserve ancient Eastern liturgical rites, spiritual traditions, and canonical disciplines while maintaining full communion with the Bishop of Rome and accepting his universal jurisdiction.[1][2] These churches, distinct from the Latin Church, originated from historical unions of Eastern Christian communities—primarily from Byzantine, Alexandrian, Syriac, Armenian, and Chaldean traditions—with the Apostolic See, beginning notably with the Union of Brest in 1596 and continuing through subsequent reconciliations.[3] Collectively, they encompass approximately 18 million faithful worldwide, organized into five major rite families and led by patriarchs, major archbishops, or metropolitans who govern with significant autonomy under papal primacy.[4] The Eastern Catholic Churches play a vital role in the Catholic Church's ecclesial diversity, safeguarding patristic heritage and serving as bridges for ecumenical dialogue with Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox communions, though they have faced controversies including accusations of proselytism from Orthodox counterparts and severe persecutions, such as forced latinizations in the past and suppression under Ottoman and Soviet regimes.[5] Key defining characteristics include married clergy in the tradition of Eastern canons, elaborate Divine Liturgies often conducted in ancient languages like Aramaic or Greek, and adherence to the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches promulgated in 1990, which affirms their equal dignity with the Latin Church.[6] Despite comprising only about 2% of global Catholics, these churches have produced influential figures and contributed to theological developments, such as clarifications on papal primacy at Vatican II's Orientalium Ecclesiarum, emphasizing their non-subordinate status.[7]

Terminology and Definitions

Distinction Between Rite, Church, and Sui Iuris Status

In the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches (CCEO), promulgated in 1990, a Church sui iuris ("of its own right") is defined as "a group of Christian faithful united by a hierarchy according to the norm of law which the supreme authority of the Church expressly or tacitly recognizes as sui iuris."[8] This designation denotes an autonomous particular church with its own internal governance, canonical discipline, and hierarchical structure, subject to the CCEO rather than the 1983 Code of Canon Law applicable to the Latin Church, while maintaining full communion with the pope as the supreme authority.[8] Distinct from the sui iuris church is the concept of rite, which Canon 28 §1 describes as "the liturgical, theological, spiritual and disciplinary patrimony, culture and circumstances of history of a distinct people, by which its own manner of living the faith is manifested in each Church sui iuris."[8] Rites represent enduring traditions rather than administrative units, often originating from ancient patriarchal sees and categorized into five primary families in the CCEO: Alexandrian, Antiochene, Armenian, Chaldean, and Constantinopolitan (Byzantine).[8] These encompass variations in liturgy (e.g., anaphoras, fasting rules), spirituality, and canon law applications, but a single rite may be professed by multiple sui iuris churches due to historical schisms, migrations, or ethnic distinctions. The particular church, as a sui iuris entity, integrates a rite into the lived experience of its faithful under a unified hierarchy, such as a patriarch, major archbishop, or metropolitan. This allows for diversity within unity: for instance, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (established 1596 via the Union of Brest) and the Melkite Greek Catholic Church (reunited 1724) both adhere to the Byzantine Rite's Constantinopolitan tradition, sharing elements like the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, yet maintain separate identities, jurisdictions, and leadership—the former under a major archbishop in Kyiv, the latter under a patriarch in Damascus.[2] Such multiplicity within a rite underscores that sui iuris status preserves ecclesial particularity, preventing assimilation into the Latin model while affirming shared Catholic doctrine. Currently, 23 Eastern Catholic Churches hold sui iuris status, enabling them to adapt rites to cultural contexts without altering core dogmas.[2]The Term "Uniate": Origins, Usage, and Controversies

The term "Uniate" originated during the Union of Brest in 1595–1596, when bishops of the Ruthenian (Ukrainian-Belarusian) eparchy, then under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, entered full communion with the Roman See amid political pressures from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, while retaining their Byzantine liturgical traditions and autonomy in non-dogmatic matters. Coined by opponents of the union, it derives from the Slavic uniya (union), denoting those who had "united" with Rome, and quickly extended to similar reconciliations, such as those in Transylvania (1697–1701) and among Maronites earlier.[9][10][11] In Catholic usage through the 19th and early 20th centuries, "Uniate" served as a neutral descriptor for these Eastern churches—totaling over 18 million faithful by 2023 across 23 sui iuris entities—emphasizing their historical unions without implying doctrinal compromise, as they affirm all Catholic dogmas including papal primacy. However, Eastern Catholics increasingly rejected it post-World War II, viewing it as reductive and implying second-class status or "latinization," a process where Roman practices encroached on Eastern traditions, often enforced by Latin-rite hierarchies until Vatican II's Orientalium Ecclesiarum (1964) mandated respect for Eastern patrimony. Orthodox critics, conversely, wielded it polemically to signify ecclesial betrayal and hybridity, associating "uniatism" with coercive proselytism backed by Western powers, as in the Brest context where only six of eleven bishops initially signed amid state incentives and threats.[12][13][14] Controversies peaked in Catholic-Orthodox dialogues, notably the 1993 Balamand Declaration, which condemned "uniatism" as an outdated method involving "proselytism" and suppression of local Orthodox hierarchies—exemplified by the 1830s suppression of the United Armenians—deeming it incompatible with mutual recognition of ecclesial equality, though it upheld the enduring validity of existing Eastern Catholic communities as "integral parts of the Catholic Church." This stance reflects causal tensions: historical unions often intertwined genuine theological convergence with geopolitical maneuvering, fostering resentment; the Vatican's pivot to "Eastern Catholic" terminology underscores a post-conciliar emphasis on parity, yet Orthodox persistence with "Uniate" perpetuates dialogue barriers, as evidenced by Moscow Patriarchate statements prioritizing its resolution.[15][16][17]Historical Development

Ancient Schisms and Doctrinal Divergences

The early Christian Church maintained doctrinal unity through the first three ecumenical councils—Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), and Ephesus (431)—which addressed Arianism, the divinity of the Holy Spirit, and Nestorianism, respectively, establishing core Trinitarian and Christological affirmations accepted by both Eastern and Western traditions.[18] However, divergences emerged with the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which affirmed the hypostatic union of Christ's two natures—fully divine and fully human—in one person, using dyophysite terminology to counter perceived monophysite excesses.[19] This definition was rejected by miaphysite churches in Egypt, Syria, Armenia, and Ethiopia, who adhered to Cyril of Alexandria's formula of "one incarnate nature of God the Word," viewing Chalcedon as introducing division in Christ or Nestorian leanings; the resulting schism severed these Oriental churches from the imperial Byzantine communion, though they preserved apostolic sees and liturgical traditions later reflected in Eastern Catholic counterparts like the Coptic Catholic and Syriac Catholic Churches.[20] By the 6th century, the Assyrian Church of the East, stemming from the 431 rejection of Ephesus over Nestorius's emphasis on Christ's distinct divine and human persons, had formalized separation in Persia, emphasizing dyothelitism but prioritizing missionary expansion eastward; this schism influenced the Chaldean Catholic Church's later union with Rome while retaining East Syriac rites.[18] Doctrinal tensions between the Chalcedonian East (Byzantine tradition) and West intensified over Trinitarian procession, with the West adopting the filioque clause—"and the Son"—in the Nicene Creed by the 6th century in Spain and Visigothic realms to combat Arianism, formally inserted in Rome around 1014, asserting the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from Father and Son as one principle.[21] Eastern theologians, rooted in Cappadocian Fathers like Gregory of Nazianzus, maintained procession from the Father alone as arche (source), arguing the filioque subordinated the Spirit or blurred hypostatic distinctions, a view hardened after Photius's 867 synod condemning it as heretical.[18] Ecclesiological rifts compounded these, with the West interpreting Matthew 16:18–19 and early synodal appeals (e.g., Clement I's letter to Corinth circa 96) as establishing Petrine primacy with universal jurisdiction for the Roman bishop, evidenced by papal interventions in Eastern disputes like the Sardica canons (343) affirming Rome's appellate role.[22] Eastern sees, while according Rome a primacy of honor as "first among equals" per Canon 6 of Nicaea (325) and the pentarchy model (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem), emphasized conciliarity and autocephaly, resisting jurisdictional overreach; this clash peaked in the Photian Schism (863–867), involving Ignatius's deposition and papal legates' involvement, foreshadowing the 1054 mutual excommunications between Patriarch Michael I Cerularius and Cardinal Humbert over azyme bread, filioque, and papal legates' authority.[23] These ancient fractures—Christological for Orientals, Trinitarian and jurisdictional for Byzantines—created distinct Eastern traditions that, despite schism, retained patristic heritage, sacraments, and canon law variations like married clergy in the East versus Western celibacy norms, setting the ecclesial landscape for later reunions forming Eastern Catholic Churches.[21][22]Formative Unions with Rome (16th–18th Centuries)