Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

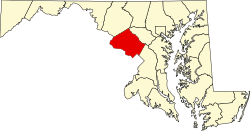

Chevy Chase, Maryland

View on WikipediaChevy Chase (/ˈtʃɛviː tʃeɪs/) is the colloquial name of an area that includes a town, several incorporated villages, and an unincorporated census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland; and one adjoining neighborhood in northwest Washington, D.C. Most of these derive from a late-19th-century effort to create a new suburb that its developer dubbed Chevy Chase after a colonial land patent.

Key Information

Primarily residential, Chevy Chase adjoins Friendship Heights, a popular shopping district. It is the home of the Chevy Chase Club and Columbia Country Club, private clubs whose members include many prominent politicians and Washingtonians.[1]

The name is derived from Cheivy Chace, the name of the land patented to Colonel Joseph Belt from Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, on July 10, 1725. It has historic associations with a 1388 chevauchée, a French word describing a border raid, fought by Lord Percy of England and Earl Douglas of Scotland over hunting grounds, or a "chace", in the Cheviot Hills of Northumberland and Otterburn.[2] The battle was memorialized in "The Ballad of Chevy Chase".

Elements

[edit]The area known as Chevy Chase includes several entities in southern Montgomery County:

- The Town of Chevy Chase, an incorporated town

- Chevy Chase, a census-designated place

- The incorporated villages of:

It also includes the neighborhood of Chevy Chase in northwest Washington, D.C.

The United States Postal Service also uses "Chevy Chase" for some postal addresses that lie outside these areas: the town of Somerset, the Village of Friendship Heights, and the part of the Rock Creek Forest neighborhood that lies east of Jones Mill Road and Beach Drive and west of Grubb Road.[3]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]In the 1880s, Senator Francis G. Newlands of Nevada and his partners began acquiring farmland in unincorporated areas of Maryland and just inside the District of Columbia, for the purpose of developing a residential streetcar suburb for Washington, D.C., during the expansion of the Washington streetcars system. Newlands and his partners founded The Chevy Chase Land Company in 1890, and its holdings of more than 1,700 acres (6.9 km2) eventually extended along the present-day Connecticut Avenue from Florida Avenue north to Jones Bridge Road.

Newlands, an avowed white supremacist, and his development company took steps to ensure that residents of its new suburbs would be wealthy and white;[4] for example, "requiring, in the deed to the land, that only a single-family detached house costing a large amount of money could be constructed. The Chevy Chase Land Company did not include explicit bars against non-white people, known as racial covenants, but the mandated cost of the house made it impractical for all but the wealthiest non-white people to buy the land." Houses were required to cost $5,000 and up on Connecticut Avenue and $3,000 and up on side streets.[5] The company banned commerce from the residential neighborhoods.[6]

Leon E. Dessez was Chevy Chase's first resident. He and Lindley Johnson of Philadelphia designed the first four houses in the area.[7]

Toward the northern end of its holdings, the Land Company dammed Coquelin Run, a stream that crossed its land, to create the manmade Chevy Chase Lake. The body of water furnished water to the coal-fired generators that powered the streetcars of the Land Company's Rock Creek Railway. The streetcar soon became vital to the community; it connected workers to the city, and even ran errands for residents.

The lake was also the centerpiece of the Land Company's Chevy Chase Lake trolley park, a venue for boating, swimming, and other activities meant to draw city dwellers to the new suburb.[8] Similar considerations led the Land Company to build a hotel at 7100 Connecticut Avenue; it opened it in 1894 as the Chevy Chase Spring Hotel and was later renamed the Chevy Chase Inn. "The hotel failed to attract sufficient patrons, especially during the winter months," wrote the Chevy Chase Historical Society, and in 1895, the Land Company leased the property for a year to the Young Ladies Seminary.[9]

Part of the original Cheivy Chace patent had been sold to Abraham Bradley, who built an estate known as the Bradley Farm.[10] In 1887, Bradley's son Joseph sold the farm, by then named "Chevy Chase" to J. Hite Miller.[11] In 1892, Newlands and other members of the Metropolitan Club of Washington, D.C., founded a hunt club called Chevy Chase Hunt, which would later become Chevy Chase Club. In 1894, the club located itself on the former Bradley Farm property under a lease from its owners. The club introduced a six-hole golf course to its members in 1895, and purchased the 9.36-acre Bradley Farm tract in 1897.[12][10][13]

20th century

[edit]In 1906, the Chevy Chase Land Company blocked a proposed subdivision called Belmont after they learned its Black developers aimed to sell house lots to other African Americans. In subsequent litigation, the company and its affiliates argued that those developers had committed fraud by proposing "to sell lots...to negroes."[14]

By the 1920s, restrictive covenants were added to Chevy Chase real estate deeds. Some prohibited both the sale or rental of homes to "a Negro or one of the African race." Others prohibited sales or rentals to "any persons of the Semetic [sic] race"—i.e., Jews.[14]

By World War II, such restrictive language had largely disappeared from real estate transactions, and all were voided by the 1948 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer.

In 1964, Arthur Krock wrote an article for The New York Times alleging that the Chevy Chase Country Club barred "Negroes" and "one ethnic group of Caucasians" from membership. In response, Club president Randall H. Hagnar denied that the club excluded Black or Jewish people; he said that no members were African-Americans but that several were Jewish.[15]

In 1903, Lea M. Bouligny bought the old Chevy Chase Inn and founded the Chevy Chase College and Seminary.[9] The name was changed to Chevy Chase Junior College in 1927. The National 4-H Club Foundation purchased the property in 1951,[16] turning it into the group's Youth Conference Center. For decades, the center hosted the National 4-H Conference, an event for 4-Hers throughout the nation to attend, and the annual National Science Bowl in late April or early May.[17]

21st century

[edit]The National 4-H Club Foundation sold the center in 2021 for $40 million; as of 2022, it is to be replaced by a senior living development.[18]

Education

[edit]Chevy Chase is served by the Montgomery County Public Schools. Residents of Chevy Chase are zoned to Somerset, Chevy Chase or North Chevy Chase Elementary School, which feed into Silver Creek Middle School, Westland Middle School and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. Private schools in Chevy Chase include Concord Hill School, Oneness-Family School, and Blessed Sacrament School.

Rochambeau French International School formerly had a campus in Chevy Chase.[19]

Retail

[edit]For decades, a six-block stretch of Wisconsin Avenue in Friendship Heights and Chevy Chase has been the only place partially or wholly in Washington, D.C., with multiple traditional department stores, namely, Bloomingdale's, Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor and Neiman Marcus.[20] The latter two closed in 2020, as did the indoor shopping center at the Chevy Chase Pavilion.[21] As of 2022, two department stores remain, both on the Maryland side: a freestanding Saks Fifth Avenue and a Bloomingdale's in a multiuse center that also includes a Whole Foods Market, boutiques, and residential and office space.

Along the D.C. stretch of Wisconsin Avenue are:

- Mazza Gallerie, home to Neiman Marcus from November 1977[22] until 2020;[21] T.J. Maxx and all other remaining tenants closed on December 24, 2022.[23] Tishman Speyer acquired the property in May 2021 for $52 million with plans to redevelop it into 350 apartments and 26,000 square feet (2,400 m2) of retail space.[24] As of March 2024, the mall is razed and a new building is being constructed for mixed-use development.

- Friendship Center, home to big-box discounter Marshalls as well as Cheesecake Factory and Maggiano's Little Italy.

- Chevy Chase Metro Center, with big-box craft retailer Michaels

- Chevy Chase Pavilion, whose shopping center with anchors Cost Plus World Market and Old Navy, closed in 2020. As of 2024, an Embassy Suites hotel and office building remain.

On the Maryland stretch are:

- Wisconsin Place, home to Bloomingdale's, Whole Foods Market, other shops and restaurants

- The Collection at Chevy Chase, an upscale, outdoor shopping center that includes a Tiffany & Co. store.

- Saks Fifth Avenue, freestanding department store

-

Neiman Marcus at Mazza Gallerie, opened 1977, closed 2020

-

Mazza Gallerie: old building razed, new building under construction, March 2024

-

Chevy Chase Pavilion (right) and Neiman Marcus (left), 2008.

-

Chevy Chase Pavilion (left) and Neiman Marcus (right), 2016

-

Chevy Chase Pavilion, empty retail and dining area, March 2024

-

The Shops at Wisconsin Place, March 2024

-

Saks Fifth Avenue

-

The Collection at Chevy Chase, panorama of Wisconsin Avenue streetfront

-

Lord & Taylor department store at opening in 1959 (closed 2020)

Notable people

[edit]Current residents

[edit]- Ann Brashares – author[25]

- John Carlson – professional ice hockey player[26]

- Pati Jinich - chef, host of Pati's Mexican Table on PBS

- Marvin Kalb – journalist[25]

- Brett Kavanaugh – associate justice, United States Supreme Court

- Tony Kornheiser – television host, currently ESPN employee presenter

- Howard Kurtz – host of Fox News program Media Buzz

- Collin Martin – soccer player

- Chris Matthews – commentator

- Jerome Powell – current Chairman of the Federal Reserve

- John Roberts – Chief Justice of the United States[25]

- A. B. Stoddard – political commentator and editor of RealClearPolitics

- George Will – conservative commentator[25]

- Portia Wu – lawyer[27]

Former residents

[edit]- Yosef Alon – Israeli Air Force officer

- Jamshid Amouzegar – former prime minister of Iran

- Tom Braden – journalist and author[28]

- David Brinkley – journalist[28]

- John Charles Daly – media personality

- Mark Ein – venture capitalist[29]

- Bill Guckeyson – athlete and military aviator

- Josh Harris – investor and sports team owner[29]

- Ed Henry – journalist

- Richard Helms – former director of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Genevieve Hughes – one of the 13 original Freedom Riders[30]

- Hubert Humphrey – 38th vice president of the United States[28]

- Gayle King – television anchor

- Ernest W. Lefever - conservative political figure

- Ted Lerner – owner of Lerner Enterprises and the Washington Nationals

- Clarice Lispector - Brazilian writer and diplomat's wife

- Willis S. Matthews – US Army major general[31]

- Anthony McAuliffe – US general

- Sandra Day O'Connor – United States Supreme Court Justice[28]

- Hilary Rhoda – model[32]

- Nancy Grace Roman – former NASA executive

- Peter Rosenberg – media personality[33]

- Danny Rubin – basketball player[34]

- Mark Shields – political columnist[25]

- Thomas S. Timberman – US Army major general[35]

- Karl Truesdell – US Army major general[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Obama to Join Maryland Country Club". Washingtonian. 2017-10-06. Archived from the original on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ "The Naming of Chevy Chase". Chevy Chase Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ Lublin, David (2014-02-14). "The Mini Munis of Chevy Chase". Seventh State. Archived from the original on 2024-02-24. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ Flanagan, Neil (2017-11-02). "The Battle of Fort Reno". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2022-05-27.

- ^ Ohmann, Richard Malin (1996). Selling Culture: Magazines, Markets, and Class at the Turn of the Century. Verso.

- ^ Dryden, Steve (1999). "The History of Chevy Chase and Friendship Heights". Bethesda Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ Benedetto, Robert; Donovan, Jane; Vall, Kathleen Du (2003). Historical Dictionary of Washington. Scarecrow Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780810840942.

- ^ "The History of Chevy Chase and Friendship Heights". Bethesda Magazine. September 27, 2010. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "Fashionable Suburban Location | Chevy Chase Historical Society". chevychasehistory.org. Archived from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ a b "The Naming of Chevy Chase | Chevy Chase Historical Society". www.chevychasehistory.org. Archived from the original on 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "Sale of "Chevy Chase"". The (Frederick, Maryland) News. 1887-01-20. p. 3. Retrieved 2025-10-10.

- ^ Early Days at the Chevy Chase Club Archived 2018-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, The Montgomery County Story, Montgomery County Historical Society, November 2001

- ^ "Chevy Chase Club - Club History". www.chevychaseclub.org. Archived from the original on 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ a b Fisher, Marc (February 15, 1999). "Chevy Chase, 1916: For Everyman, a New Lot in Life". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Country Club Denies Excluding Jews from Membership". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Archived from the original on 2023-06-20. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ "The Schools of Section Four - Chevy Chase Historical Society". Chevy Chase Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy, National Science Bowl®". United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ Schere, Dan (2021-12-21). "Sale of 4-H site in Chevy Chase finalized for $40 million". Bethesda Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ^ "Contacts". Rochambeau French International School. Archived from the original on 2000-01-23. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ "Friendship Heights Retail Action Strategy: Friendship Heights Strategic SWOT Analysis" (PDF). Office of Planning, District of Columbia Government. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b https://www.popville.com/2020/12/friendship-heights-is-looking-more-and-more-bare/

- ^ Pressler, Margaret Webb (February 26, 1998), "The 'De-Malling' of Mazza Gallerie", The Washington Post, retrieved 2022-07-12

- ^ Wells, Clara (2022-12-25). "Mazza Gallerie shopping center permanently closes". WTOP News. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ Sernovitz, Daniel J. (May 25, 2021). "Mazza Gallerie sold, to be redeveloped under new owner". American City Business Journals.

- ^ a b c d e Neate, Rupert (December 4, 2015). "Chevy Chase, Maryland: the super-rich town that has it all – except diversity". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Hull, Steve (July 23, 2018). "Washington Capitals' John Carlson Buys Home in Chevy Chase". Bethesda Magazine. Archived from the original on April 3, 2023. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Pollak, Suzanne (2023-01-12). "Chevy Chase's Wu Named Secretary of Labor for Moore Administration". Montgomery Community Media. Archived from the original on 2023-03-23. Retrieved 2024-10-20.

- ^ a b c d "Bethesda, Chevy Chase Homes of The Rich and Famous". Bethesda Magazine. October 10, 2012. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Elfin, David (July 6, 2015). "Q&A with the Owners of the Philadelphia 76ers, New Jersey Devils and Washington Kastles". MoCo360. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006), Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199755813, archived from the original on 2024-02-25, retrieved 2020-10-25

- ^ "Maj. Gen. W. S. Matthews Dies". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. 30 March 1981. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2025.

- ^ "Hilary Rhoda - Fashion Model - Profile on New York Magazine". New York. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ^ Richards, Chris (May 31, 2013). "Peter Rosenberg: From Montgomery County to top of the hip-hop heap". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Giannotto, Mark (February 4, 2011). "Danny Rubin goes from Landon to Boston College walk-on to ACC starter". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ DJL (September 1990). "Obituary, Royal B. Lord". Assembly. West Point, New York. pp. 85–88 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Obituaries: Maj. Gen. Karl Truesdell". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, IL. Associated Press. July 18, 1955. p. F6. Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

[edit]Chevy Chase, Maryland

View on GrokipediaGeography and Demographics

Location and Boundaries

Chevy Chase comprises several incorporated villages and towns along with unincorporated neighborhoods in the southern section of Montgomery County, Maryland, forming a residential suburb immediately northwest of Washington, D.C.[3][4] The area is centered at approximately 38.97° N latitude and 77.08° W longitude, about 5-6 miles northwest of the U.S. Capitol.[5][6] Its southern extent borders the District of Columbia along the state line, coinciding with Western Avenue near Wisconsin and Connecticut Avenues.[3] The Town of Chevy Chase, one of the principal incorporated areas, has boundaries extending to East-West Highway (Maryland Route 410) on the north, Bradley Lane on the south, Connecticut Avenue on the east, and partially one block further east in some sections.[2] Chevy Chase Village, located immediately south and also bordering D.C., spans just under 0.5 square miles (approximately 1.2 km²), with its northern boundary along the south side of Bradley Lane east of Connecticut Avenue.[3][7] To the west lies Bethesda, while eastern sections adjoin Friendship Heights, a commercial district straddling the MD-DC line.[8]Topography and Climate

Chevy Chase lies within the Piedmont physiographic province of Maryland, featuring gently rolling hills and valleys typical of the region's terrain. Elevations in the area generally range from 200 to 400 feet (61 to 122 meters) above sea level, with an average around 361 feet (110 meters) in central sections.[9] Local topography includes modest variations, with elevation changes of up to 299 feet over short distances of 2 miles, contributing to a landscape of subtle undulations rather than steep inclines.[10] The area is drained by tributaries of Rock Creek, such as Coquelin Run, which carve minor valleys and influence soil distribution in this glacial till and weathered bedrock environment.[11] The climate of Chevy Chase is classified as humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa), characterized by four distinct seasons with hot, humid summers and cool, occasionally cold winters moderated by its proximity to Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake Bay. Average high temperatures reach 87°F (31°C) in July, while January lows average 27°F (-3°C), with extremes rarely exceeding 95°F (35°C) or dropping below 15°F (-9°C).[10] Annual precipitation totals approximately 43 inches (109 cm), distributed fairly evenly but peaking in May at 3.5 inches (89 mm), supporting lush vegetation while contributing to occasional flooding in low-lying areas near streams.[12] Snowfall averages 16 inches (41 cm) per year, primarily from December to March, though accumulation is often light due to mid-Atlantic weather patterns.[12] Relative humidity remains high year-round, averaging 67% in summer months, which amplifies perceived temperatures during heat waves.[13]Population Trends

The population of Chevy Chase Village has exhibited relative stability with minor fluctuations since the late 20th century, reflecting its status as a mature, land-constrained residential community with approximately 720 single-family homes. Decennial census data indicate a slight overall decline from 1990 to 2010, followed by a modest rebound.[14][15]| Census Year | Population | Change from Prior Census |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2,076 | — |

| 2000 | 2,043 | -33 (-1.6%) |

| 2010 | 1,953 | -90 (-4.4%) |

| 2020 | 2,049 | +96 (+4.9%) |

Racial and Socioeconomic Composition

As of the 2023 American Community Survey estimates, Chevy Chase Village's population stood at approximately 1,860 residents, with White non-Hispanic individuals comprising 89.1% of the total.[19] Hispanic or Latino residents of any race accounted for about 5.2%, primarily consisting of White Hispanic (2.3%) and multiracial Hispanic (3.0%) groups, while non-Hispanic multiracial residents made up roughly 3.8%.[20] Black or African American and Asian populations each represented less than 1% of the total, reflecting minimal diversity relative to national averages.[19]| Race/Ethnicity | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 89.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 5.2% |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | 3.8% |

| Black or African American | <1% |

| Asian | <1% |

History

Founding and Early Development (Late 19th to Early 20th Century)

In the late 1880s, Nevada Senator Francis G. Newlands and his associates, including Senator William Stewart, began acquiring farmland in the unincorporated area of Montgomery County, Maryland, straddling the border with Washington, D.C., with the aim of developing it into an exclusive residential suburb for the capital's elite.[22] [23] Newlands' key early purchase was a 305-acre tract known as Chevy Chase, which extended across the Maryland-D.C. line.[2] The name "Chevy Chase" originated from "Cheivy Chace," a colonial land patent granted to Colonel Joseph Belt by Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore, on July 10, 1725, though the area remained largely rural farmland until this period.[2] The Chevy Chase Land Company was formally established in 1890 by Newlands and his partners, securing holdings exceeding 1,700 acres (6.9 km²) primarily along the route of the planned Connecticut Avenue extension.[22] [24] This entity drove initial development by platting subdivisions, constructing the Calvert Hotel in the early 1890s as a promotional centerpiece to attract potential buyers, and integrating electric streetcar lines to facilitate commuting to downtown Washington, D.C.[25] [22] These efforts positioned Chevy Chase as a "home suburb for the nation's capital," emphasizing spacious lots, wooded landscapes, and restrictive covenants to ensure affluent, homogeneous residency.[22] By the early 1900s, the Land Company had subdivided core sections—such as Sections 1, 1A, and 2 in Maryland—into what became Chevy Chase Village, with initial sales of large estate lots averaging 1-2 acres each.[2] [26] Amenities like the Chevy Chase Club, founded in 1895 with an 18-hole golf course designed by Robert Lockhart, further enhanced appeal, drawing prominent figures including senators and cabinet members as early residents.[27] Development progressed methodically, with infrastructure such as graded roads and utilities installed by 1910, though full build-out remained gradual due to the emphasis on custom homes rather than speculative construction.[24] This era cemented Chevy Chase's status as a premier planned suburb, predicated on proximity to federal power centers and exclusionary land-use policies.[22]Expansion and Incorporation (1920s to 1950s)

During the 1920s, Chevy Chase experienced rapid residential expansion driven by the Chevy Chase Land Company's ongoing subdivision efforts, which transformed remaining farmland into single-family home lots equipped with modern utilities.[2] This period saw a surge in home construction, with the population density increasing as Washington, D.C., commuters sought suburban living accessible via streetcar lines along Connecticut Avenue and Wisconsin Avenue.[2] Infrastructure developments, including expanded street paving, lighting, and sanitation systems, accompanied this growth to accommodate the rising number of households.[2] The Great Depression temporarily slowed development in the 1930s, but post-World War II demand revived expansion into the 1940s and early 1950s, with Montgomery County's overall population rising from approximately 49,000 in 1930 to over 164,000 by 1950, reflecting broader suburbanization trends that included Chevy Chase.[28] New subdivisions filled in gaps between earlier sections, emphasizing large-lot, low-density housing that preserved the area's wooded, estate-like character.[29] Incorporation efforts during this era focused on local governance to manage growth and services independently from Montgomery County. In 1922, residents of what became Chevy Chase Section 5 organized as a special taxing district to fund street improvements and maintenance.[30] Similarly, the Village of North Chevy Chase was established as a special taxing district in 1924 by act of the Maryland General Assembly, enabling targeted property assessments for roads and policing.[31] Full municipal incorporation culminated in 1951 with the creation of Chevy Chase Village, encompassing original land company sections 1, 2, parts of 1(a), 6, and 7, granting it authority over zoning, policing, and public works.[32][33] These steps reflected residents' preference for insulated, community-controlled administration amid accelerating regional development pressures.[2]Post-War Evolution and Modern Era (1960s to Present)

The completion of Interstate 495, known as the Capital Beltway, in August 1964 enhanced connectivity for Chevy Chase residents to Washington, D.C., and surrounding areas, supporting continued suburban expansion in Montgomery County during the post-war period.[34] The Friendship Heights Metro station on the Red Line opened on August 25, 1984, providing direct rail access to downtown D.C. and further integrating the area into the regional transit network.[35] These infrastructure improvements coincided with modest population growth in the Town of Chevy Chase, from 2,243 residents in 1960 to 2,904 by 2020, reflecting stable development in an established affluent suburb.[36] Commercial activity in the adjacent Friendship Heights district, straddling the D.C.-Maryland line, expanded in the late 1950s and 1970s with the arrival of major retailers. Lord & Taylor opened its Chevy Chase store in October 1959 as an anchor for the area, operating until its closure on February 27, 2021, amid the chain's bankruptcy.[37] Neiman Marcus established a presence at Mazza Gallerie in 1977, which itself debuted as an upscale indoor mall in the late 1970s before facing decline.[38] Zoning adjustments in the 1960s permitted taller structures in Friendship Heights, fostering vertical commercial growth while Chevy Chase proper maintained restrictions favoring low-density residential use.[35] The 21st century brought challenges to traditional retail, with e-commerce competition and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating store closures, including Neiman Marcus in 2020 and the full shuttering of Mazza Gallerie by December 2022, resulting in over 467,000 square feet of vacant space.[39] In response, redevelopment efforts transformed these sites into mixed-use properties; the former Mazza Gallerie site is being converted into residential apartments with ground-floor retail, attracting new tenants such as Total Wine & More and a Wonder food hall by 2025.[40] Local zoning policies have preserved the area's single-family residential character, limiting high-density infill and emphasizing community opposition to overdevelopment.[28]Government and Politics

Local Governance Structure

Chevy Chase, Maryland, functions as an unincorporated census-designated place (CDP) encompassing a patchwork of small incorporated municipalities and unincorporated territories, with local governance divided accordingly. Incorporated areas maintain autonomous town or village councils responsible for enacting and enforcing ordinances on matters such as zoning, building regulations, parks, and sidewalks, while deferring broader services like public safety, education, and utilities to Montgomery County. Unincorporated portions are directly administered by Montgomery County's charter government, which features an elected County Executive and a nine-member County Council handling legislative powers, budgeting, and regional planning across the county's 497 square miles.[41][42] The primary incorporated entities within or adjacent to the CDP include the Town of Chevy Chase (formerly Section 4, incorporated 1918), governed by a five-member Town Council elected biennially in May for two-year terms, which oversees legislative decisions, administrative policies, and committees on parks, trees, safety, and infrastructure.[43][44] Chevy Chase Village (chartered to include Sections 1, 2, part of 1A, 6, and 7) operates under a similar council structure with standing committees addressing governance, policy, and community programs, such as senior services.[45][33] Section 3 of Chevy Chase, incorporated as a village in 1982 after prior status as a special taxing district, features a five-member Village Council elected for two-year terms, focused on ordinance enforcement including building codes within its subdivision boundaries established by the Chevy Chase Land Company.[46][47][48] Additional villages like Section 5 (incorporated 1982) and Chevy Chase View maintain self-governed municipal structures empowered to regulate local functions, though their populations remain small—e.g., the Town of Chevy Chase recorded 2,904 residents in the 2020 census.[49][50] This fragmented model reflects early 20th-century subdivision patterns, allowing hyper-local control in affluent residential zones while relying on county-level coordination for unified services; for instance, Montgomery County manages roads that cross municipal boundaries via mutual agreements.[51] No single overarching municipal government exists for the entire CDP, distinguishing it from fully incorporated cities like nearby Rockville or Gaithersburg.[52]Political Leanings and Voter Behavior

Chevy Chase residents exhibit a pronounced preference for Democratic candidates in national elections, mirroring patterns across Montgomery County, where factors such as high education levels, affluence, and proximity to federal institutions foster liberal voting behavior. In the 2020 presidential election, Montgomery County voters supported Joe Biden with 78.6% of the vote compared to 19.0% for Donald Trump, with remaining votes for other candidates.[53] Precinct-level breakdowns for Chevy Chase were not reported due to Maryland's universal mail-in ballot distribution amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which aggregated results at the county level.[54] Similar margins prevailed in the 2024 presidential contest, where Kamala Harris secured Montgomery County by approximately 75-80%, continuing the area's role as a Democratic stronghold that offsets more conservative regions in Maryland.[55] Voter registration in Montgomery County tilts heavily Democratic, with roughly 55% of active voters affiliated with the party, 15% Republican, and the balance independent or other, influencing primary outcomes where Chevy Chase precincts show elevated turnout among high-income households. This demographic—characterized by professionals commuting to Washington, D.C.—prioritizes issues like environmental policy and public services, contributing to consistent Democratic victories in congressional races for Maryland's 8th District, which encompasses Chevy Chase and returned over 70% support for Democratic incumbents in recent cycles. Local elections for Chevy Chase's municipal bodies, such as the Town Council or Village Board of Managers, are non-partisan and emphasize administrative matters like zoning and infrastructure maintenance rather than ideological divides. Turnout in these contests is moderate, as seen in a 2014 Town of Chevy Chase council election where 889 of 2,574 registered voters participated, yielding a 35% rate.[56] Despite the absence of party labels, candidates often align with progressive priorities on community preservation, reflecting the electorate's overall left-leaning composition without the polarization of national politics. High presidential turnout in the area, frequently surpassing county medians due to socioeconomic predictors like household income exceeding $250,000, underscores engaged civic participation.[57]Economy and Retail

Commercial Districts and Businesses

The primary commercial district in Chevy Chase, Maryland, centers on the Friendship Heights area along Wisconsin Avenue, near the border with Washington, D.C., featuring upscale shopping centers, department stores, and mixed-use developments that serve affluent residents and commuters.[58] This district has historically anchored retail activity, with major anchors including Saks Fifth Avenue, which operates at 5345 Wisconsin Avenue as a flagship store offering luxury apparel and home goods.[59] Key shopping venues include The Shops at Wisconsin Place, an open-air center at 5310 Western Avenue that integrates retail, dining, and residential elements within a larger mixed-use complex developed in the mid-2000s; it hosts boutiques, restaurants, and services such as Urbano Tex-Mex and a planned food hall, with over 2,000 parking spaces supporting visitor traffic.[60] Adjacent, The Collection at Chevy Chase at 5471 Wisconsin Avenue comprises a retail plaza with tenants like Tiffany & Co., Capital One, and Clyde's restaurant, alongside ongoing redevelopment to enhance public spaces and storefronts amid efforts to revitalize the corridor.[61] Formerly prominent sites reflect retail shifts: Mazza Gallerie, opened in 1979 at 5300 Wisconsin Avenue, once housed Neiman Marcus (from 1977 until its 2020 closure after 43 years) but deteriorated into high vacancy post-pandemic, leading to its 2020 foreclosure and razing for a mixed-use project with 1,400 multifamily units, luxury penthouses, restaurants, and retail by 2023 plans.[62][63] Similarly, Chevy Chase Pavilion at Wisconsin Avenue and Western Avenue, a mixed-use site built atop the Friendship Heights Metro, saw anchors like Lord & Taylor (opened 1959, closed 2020) depart amid decline, prompting redevelopment including a Trader Joe's grocery store slated for winter 2025 opening to anchor renewed retail vitality.[64] These transformations underscore adaptation to e-commerce pressures and demographic changes, with district-wide efforts focusing on experiential retail and residential integration.[65]Employment and Commuting Patterns

In Chevy Chase, the civilian labor force participation rate for residents aged 16 and over was 65.0% during 2019-2023, reflecting a highly educated populace with selective workforce engagement. Of the approximately 4,870 employed residents in 2023, the dominant sectors included professional, scientific, and technical services (1,266 workers), public administration (621), health care and social assistance (487), finance and insurance (425), and educational services (421).[66][67] These concentrations align with the area's socioeconomic profile, where federal government-related roles in Washington, D.C., and consulting firms predominate, supplemented by local employers like GEICO's headquarters providing insurance positions.[68] Retail and service jobs in adjacent Friendship Heights contribute marginally, but overall local employment remains limited due to the village's primarily residential character.[69]| Sector | Employed Workers (2023) |

|---|---|

| Professional, Scientific, & Technical Services | 1,266 |

| Public Administration | 621 |

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 487 |

| Finance & Insurance | 425 |

| Educational Services | 421 |

Education

Public Schools

Public education in Chevy Chase, Maryland, is administered by Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS), the 16th largest school district in the United States by enrollment.[71] The area falls within the Bethesda-Chevy Chase cluster, which encompasses several high-performing elementary schools feeding into Silver Creek Middle School and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School.[72] School assignments vary by specific neighborhood within Chevy Chase's sections, but residents generally access schools noted for above-average academic outcomes relative to state averages.[73] At the elementary level, Chevy Chase Elementary School serves grades 3–5 at 4015 Rosemary Street, with an enrollment of 431 students as of recent data; it reports 69% proficiency in mathematics and 74% in reading on state assessments, ranking it among the top performers in Maryland.[74][75] Lower elementary grades (K–2) in parts of Chevy Chase are often assigned to nearby schools such as Rosemary Hills Primary School or North Chevy Chase Elementary School, both within the district and contributing to the cluster's strong foundational education metrics.[76] Other cluster elementaries like Rock Creek Forest Elementary (offering Spanish immersion) and Somerset Elementary also draw students from the vicinity, with Somerset ranking 57th out of 865 Maryland elementaries based on test scores.[72][77] Middle school students typically attend Silver Creek Middle School in Kensington, which serves grades 6–8 and feeds into the high school level.[76] Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School, located on East-West Highway in Bethesda, enrolls grades 9–12 and serves as the primary high school for Chevy Chase residents; it ranked 10th among Maryland high schools in 2024 U.S. News evaluations, with a national ranking of 590, based on state test performance, graduation rates (95%), and college readiness metrics.[78] The school's AP participation rate exceeds 60%, reflecting robust advanced coursework access.[79] Overall, MCPS schools in this area benefit from the community's socioeconomic profile, though district-wide challenges like resource allocation persist.[80]Private Schools and Libraries

Concord Hill School, an independent early childhood institution founded in 1965, serves students from ages three through third grade in Chevy Chase, Maryland.[81] The school enrolls about 120 students, maintaining a student-teacher ratio of 6:1, with a curriculum emphasizing hands-on learning and nurturing relationships to foster curiosity.[82] Approximately 32% of its students are from minority backgrounds, and it reports 100% placement into subsequent schools.[83] Oneness-Family School, established in 1988 as a nonprofit Montessori program, provides education from toddler through twelfth grade at 6701 Wisconsin Avenue in Chevy Chase.[84] It serves 126 students with a focus on academic, social, and emotional development in a diverse environment representing families from 75 countries.[85] [86] The school's student-centered approach integrates Montessori principles with innovation, serving as one of the few full-range Montessori options in the area.[87] Smaller specialized private schools, such as the Alvin Browdy Religious School at Ohr Shalom, offer supplementary Jewish education but enroll fewer students and focus on religious instruction rather than full-day academics.[88] Larger nearby institutions like Sidwell Friends School in Bethesda serve Chevy Chase residents but are located outside the village limits.[89] The Chevy Chase Library, a branch of the Montgomery County Public Libraries system, operates at 8005 Connecticut Avenue and serves approximately 9,800 residents in the community.[90] [91] It features collections for children and teens, along with public programming, and maintains hours of 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Wednesday.[92] The library supports local literacy initiatives through groups like the Friends of Chevy Chase Library, which fund enhancements via book sales and donations.[93] No major private libraries are documented within Chevy Chase, with residents relying primarily on this public facility and adjacent county branches.[90]Transportation and Infrastructure

Roadways and Highways

Chevy Chase is accessed primarily through Maryland Route 185 (Connecticut Avenue), a six-lane divided highway serving as the community's central north-south arterial from the District of Columbia boundary northward through affluent residential neighborhoods. This route connects directly to Interstate 495 (Capital Beltway) at Exit 33, approximately 2 miles north of the town center, facilitating commuter access to Washington, D.C., and surrounding suburbs.[94][95] Maryland Route 410 (East–West Highway) forms the town's northern boundary, functioning as a key east-west collector road that intersects MD 185 and links to broader Montgomery County roadways like MD 355 (Rockville Pike). Supporting routes include Maryland Route 191 (Bradley Boulevard), which approaches from the west and terminates at MD 185, and adjacent segments of Wisconsin Avenue (MD 355), a major north-south corridor just to the west in Friendship Heights that sees heavy commuter traffic. These state highways are maintained and improved by the Maryland State Highway Administration, with recent projects focusing on safety enhancements such as signal upgrades along MD 355 between the D.C. line and MD 191.[96][97] Shorter connectors, such as Maryland Route 186 (Brookville Road), provide local linkages from the D.C. boundary to MD 410. The roadway network emphasizes arterial connectivity over high-capacity freeways, aligning with Chevy Chase's planned residential layout, though this results in congestion during peak hours as residents commute via these routes to the Beltway.[96][98]Public Transit Options

Chevy Chase residents primarily access public transit through the Washington Metro Red Line at the Friendship Heights station, which lies approximately one mile from central areas of the community and straddles the Maryland-District of Columbia border.[99] This underground station, opened on August 25, 1984, provides bidirectional service toward downtown Washington, D.C., (via stations like Dupont Circle and Metro Center) and Shady Grove in Montgomery County, with trains operating from 5:00 a.m. on weekdays and extending service until after midnight on most days.[99] Peak-hour frequencies reach every 3-6 minutes, facilitating commutes to federal offices, employment centers, and regional hubs.[100] Local bus service is provided by Montgomery County's Ride On system, which connects residential neighborhoods in Chevy Chase to the Friendship Heights Metro station and other destinations. Route 1, for example, runs from Silver Spring Transit Center to Friendship Heights Metro, stopping at key points including Chevy Chase Circle, Connecticut Avenue, and East-West Highway, with service intervals of 15-30 minutes during peak periods as of the July 2024 system map.[101][102] Additional routes such as 11 (serving Bethesda via Chevy Chase areas) and 29 (connecting to Rockville Pike) offer frequent links, enhanced by the Ride On Reimagined network launched in phases starting June 29, 2025, which improved alignment with high-demand corridors.[103][104] WMATA Metrobus routes supplement Ride On coverage, particularly along major arterials like Wisconsin Avenue and East-West Highway. The M70 route operates east-west from Silver Spring to Montgomery Mall, passing through Chevy Chase stops such as East-West Highway at Summit Hills Apartments, with express elements during rush hours.[105] Transfers between Ride On, Metrobus, and Metrorail are free within two hours using SmarTrip cards, which cost $2 and support contactless payments; standard local bus fares are $1.50, while Metro rail trips start at 6.75 depending on distance and time.[102] No direct commuter rail or light rail service exists within Chevy Chase as of October 2025, though the Purple Line light rail, under construction, will connect to nearby Bethesda station upon its anticipated opening in 2027.[106]Community and Culture

Parks, Recreation, and Landmarks

Chevy Chase features several small municipal parks maintained by local jurisdictions, including Zimmerman Park, Rosemary Triangle, Rosemary Circle, Thornapple Path, and Tarrytown Park, which provide limited greenspace for passive recreation in the Town of Chevy Chase.[107] Larger facilities under Montgomery Parks include Chevy Chase Local Park at 3315 Shepherd Street, offering open fields and trails open from sunrise to sunset, and North Chevy Chase Local Park on Jones Bridge Road, equipped with a baseball field, soccer field, playground, and parking.[108][109] Meadowbrook Local Park provides extensive athletic amenities, such as a large playground, five softball fields, a lighted baseball field, and four lighted tennis courts, with handicap accessibility throughout.[110] Recreation options emphasize community centers and trails. The Jane E. Lawton Community Recreation Center at 4301 Willow Lane offers programs including fitness classes and youth activities for all ages.[111] Nearby, the Wisconsin Place Community Recreation Center at 5311 Friendship Boulevard hosts multi-purpose facilities for fitness, youth sports, and toddler programs.[112] The Capital Crescent Trail, an 11-mile multi-use path following an abandoned railroad right-of-way, passes through the area and connects to broader regional networks for hiking and cycling.[113] Portions of Rock Creek Park, a 1,754-acre federal preserve established in 1890, extend into Chevy Chase, providing wooded trails, wildlife viewing, and access to the Rock Creek Nature Center.[113] Notable landmarks include the Audubon Naturalist Society's Woodend Sanctuary, a 40-acre nature preserve with trails, a mansion, and educational programs focused on local ecology, serving as a key site for birdwatching and conservation since its establishment.[114] The former National 4-H Youth Conference Center, located in Chevy Chase and used for youth leadership events as recently as April 2013, is slated for redevelopment into senior housing, marking a shift from its agricultural education role. Western Grove Urban Park, a 1.9-acre site in Chevy Chase Village, prioritizes natural preservation with contemplative areas and minimal development.[116]Civic Organizations and Events

The Chevy Chase Historical Society, established in 1981 as a nonprofit volunteer organization, preserves and disseminates the history of Chevy Chase, Maryland, one of America's early streetcar suburbs, through archival collections, research resources, and public programs. Its archive and research center, accessible by appointment, houses materials on local development from farmland to suburbia, including landmarks and heritage stories.[117][118][119] The Woman's Club of Chevy Chase, founded in 1913, advances community welfare in Maryland through membership activities, facility rentals for social gatherings, and events promoting state interests. It operates from 7931 Connecticut Avenue, hosting programs that foster civic engagement among residents.[120] Chevy Chase At Home, a volunteer-driven nonprofit, supports older adults in the community by building networks for assistance, social connections, and aging-in-place services tailored to local needs.[121] The Bethesda-Chevy Chase Rotary Club, drawing members from the area including Chevy Chase, Maryland, conducts weekly meetings at the Chevy Chase Women's Club and undertakes service projects such as weekend food distributions to elementary schools, environmental cleanups, and support for local and international charities via its foundation.[122][123][124] Civic associations like the Elm Street-Oakridge-Lynn Civic Association represent neighborhood interests in Chevy Chase, participating in county-level civic networks to address local governance and development issues. Community events in Chevy Chase, Maryland, primarily consist of town-sponsored meetings, seasonal neighborhood gatherings, and preservation activities. The Town of Chevy Chase and Chevy Chase Village maintain public calendars for council sessions, board meetings, and occasional special events such as Halloween costume parades and Montgomery Preservation Inc. awards ceremonies recognizing historic efforts.[125][126] Local sections organize farmer's markets, food truck visits, and outdoor movie nights in parks, typically held on weekends from spring through fall.[127] Rotary-led initiatives include annual community service drives, while the Historical Society hosts talks and exhibits on regional history, often in coordination with preservation groups.[117][123] These activities emphasize resident participation in governance and maintenance of suburban character, with limited large-scale festivals compared to urban centers.[128]Controversies and Criticisms

Historical Racial Restrictive Covenants

In the 1920s, real estate deeds in Chevy Chase, Maryland, began incorporating racially restrictive covenants that explicitly prohibited the sale, lease, or occupancy of properties by individuals of non-Caucasian descent, aiming to preserve a racially homogeneous residential community.[129] These provisions typically barred conveyance "to any person of negro blood or extraction" or "any person not of the Caucasian race," reflecting broader practices in early suburban developments to exclude Black residents and other minorities through private contractual agreements enforceable via deed restrictions.[129] Such covenants were embedded in subdivisions like Chevy Chase Park, contributing to Montgomery County's pattern of segregated housing by the 1930s, where at least 20 local developments included similar racial exclusions.[130] The Chevy Chase Land Company, which spearheaded the area's subdivision from the 1890s onward, played a central role in implementing these measures, often delaying or blocking alternative developments that might have integrated non-white buyers, as seen in the stalled 1906 Belmont project by African American developers along Wisconsin Avenue.[131] The U.S. Supreme Court's 1926 decision in Corrigan v. Buckley, upholding private racial covenants against constitutional challenges in a case involving nearby Washington, D.C., properties, bolstered their legal standing and facilitated their widespread adoption in Chevy Chase until judicial enforcement was invalidated nationwide in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948).[132] Despite losing court enforceability, the covenants persisted in deed language, deterring integration; local accounts from the 1960s describe community backlash against potential Black buyers, underscoring their enduring social impact.[129] Federal legislation finally rendered these covenants void with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in housing sales and rentals, though remnants lingered in property records until targeted removal efforts in subsequent decades.[133] In Chevy Chase, this history of exclusion via covenants contributed to the suburb's demographic profile, with non-enforcement post-1948 coinciding with gradual diversification only after broader civil rights advancements eroded informal barriers.[131]Modern Development and Equity Disputes

In recent decades, Chevy Chase, Maryland, has seen targeted redevelopment efforts aimed at updating aging infrastructure and commercial spaces while navigating strict zoning and community preferences for low-density preservation. The Chevy Chase Lake sector plan, approved by Montgomery County in 2013 following extensive resident input, facilitated a mixed-use development including 280 apartment units, 77,000 square feet of retail space, and a 685-space parking garage, with amenities like a fitness center and resident lounge.[134] This project, completed in phases through the 2020s, consolidated lots for up to 246,454 square feet of development, incorporating 12.5% moderately priced dwelling units (MPDUs) as required by county law.[135] Similarly, the town's civic core—encompassing the neighborhood library and community center—drew eight redevelopment proposals in early 2025 from teams vying to modernize facilities with potential additions of housing and enhanced public amenities, amid ongoing debates over building heights limited generally to 10 feet per story.[136] [137] These initiatives have intersected with broader Montgomery County policies promoting housing equity through attainable housing strategies (AHS), which seek to amend land-use regulations to enable more diverse housing types accessible to middle- and lower-income households.[138] However, public listening sessions on AHS in 2024 revealed significant opposition concentrated in Chevy Chase's 20815 ZIP code, where one-third of participants originated, often citing concerns over increased density, traffic, and erosion of single-family neighborhood character.[139] Residents have historically resisted infrastructure changes perceived as disruptive, such as the town's multi-decade opposition to the Purple Line light rail project, which delayed regional transit expansions until its partial opening in 2023.[139] Equity disputes intensified around mandates for affordable units in new builds, exemplified by the Lindley apartments in Chevy Chase, constructed via private developers with county Housing Opportunities Commission funding to include income-restricted units alongside market-rate ones.[140] Critics from the community argue that such integrations strain local resources like schools and roads without commensurate benefits, while proponents, including county officials, contend that exclusionary resistance perpetuates high barriers to entry in an area with median home values exceeding $1.5 million as of 2023. These tensions reflect causal dynamics where affluent enclaves prioritize property value stability over regional housing needs, leading to legal and procedural challenges that slow development; for instance, early Chevy Chase Lake planning in 2013 prompted resident groups to demand scaled-back heights and parking adjustments before approval.[141] Despite this, projects like the 300-unit, 18-story residential tower at 5500 Wisconsin Avenue proceeded in the 2020s, balancing retail ground floors with MPDU requirements.[142] Commercial redevelopments along bordering corridors, such as the razing and reconstruction of Mazza Gallerie starting in 2023, underscore adaptive reuse amid retail vacancies, with the site shifting from enclosed malls to open-air formats to attract modern tenants.[143] Equity advocates highlight how such evolutions often favor luxury or senior-oriented housing—like the planned conversion of the former 4-H Youth Conference Center into senior residences—potentially sidelining broader affordability goals, though county incentives continue to enforce inclusionary zoning.[144] Overall, these disputes pit local autonomy against county-wide imperatives for equitable access, with outcomes hinging on procedural votes and empirical assessments of infrastructure capacity.Notable Residents

Political and Governmental Figures

Hubert Humphrey, who served as the 38th Vice President of the United States from January 20, 1965, to January 20, 1969, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, maintained a residence at 3216 Coquelin Terrace in Chevy Chase, Maryland, during his vice presidency.[145] The home, valued at approximately $40,000 at the time, was described as modest and was shared with his wife, Muriel, reflecting a preference for suburban stability amid his political duties.[145] Prior to this, Humphrey had represented Minnesota as a U.S. Senator from 1949 to 1964 and 1971 to 1978, focusing on civil rights legislation and social welfare policies. His Chevy Chase address facilitated proximity to Washington, D.C., for governmental functions. Sandra Day O'Connor, appointed as the first female Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan on July 1, 1981, and serving until her retirement on January 31, 2006, resided in Chevy Chase during much of her tenure on the bench. She and her husband purchased a home at 4 Oxford Street in 1992, living there until 2005 when they relocated to a Washington, D.C., townhouse amid health considerations for her husband.[146] O'Connor's jurisprudence often emphasized federalism, judicial restraint, and pragmatism, authoring key opinions in cases involving abortion, affirmative action, and presidential elections. The Chevy Chase location, in an affluent suburb, aligned with the residential patterns of high-level federal officials seeking secure, family-oriented environments near the capital.[147]Cultural and Business Leaders

Annette Lerner, widow of real estate developer Theodore N. Lerner, has resided in Chevy Chase since at least 2000, overseeing the family's Lerner Enterprises, founded by her husband in 1952 as a small building firm that grew into a major Washington-area developer with holdings including Nationals Park stadium.[148] [149] [150] The Lerner family's net worth stood at $6.5 billion in 2023, derived primarily from commercial and residential properties.[148] Bernard Francis Saul II, a longtime Chevy Chase resident, serves as chairman and CEO of Saul Centers, Inc., a publicly traded real estate investment trust managing shopping centers and office properties across the Mid-Atlantic; he also founded Chevy Chase Bank in 1969, which expanded into the region's largest independent bank before its $476 million sale to Capital One in 2009.[151] [152] [153] His business activities trace to the B.F. Saul Company, established by his grandfather in 1892 as a mortgage brokerage that evolved into diversified real estate operations.[154] Scott Nash founded MOM's Organic Market in 1987 at age 22 with a $100 investment for home delivery from his garage, building it into a regional chain of 18 organic grocery stores by emphasizing sustainable sourcing and local produce; as CEO, he has advocated for reduced food waste, including a personal experiment consuming expired products.[155] [156] Nash, who grew up in Beltsville, Maryland, has maintained a home in Chevy Chase.[156] In cultural spheres, Pati Jinich, a Chevy Chase resident since at least 2009, hosts the PBS series Pati's Mexican Table (premiered 2011), authored three cookbooks, and serves as resident chef at the Mexican Cultural Institute, blending Mexican heritage with American audiences through public television reaching millions.[157] [158] [159] Ann Brashares, raised in Chevy Chase, achieved prominence as an author with The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants (2001), the first in a young adult series selling over 10 million copies worldwide and adapted into two films (2005, 2008); her works explore themes of friendship and growth among teenage girls.[160] Marvin Kalb, a long-time Chevy Chase resident, is a veteran broadcast journalist who covered diplomacy for NBC and CBS News from the 1950s to 1980s, moderated Meet the Press from 1985 to 1987, and founded Harvard's Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy in 1986, influencing journalism education and analysis.[161] [162]References

- ./assets/National_4-H_Youth_Conference_Center_where_Agriculture_Secretary_Tom_Vilsack_spoke_with_National_Youth_Leadership%252C_on_Monday%252C_April_8%252C_2013%252C_in_Chevy_Chase%252C_MD.jpg