Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

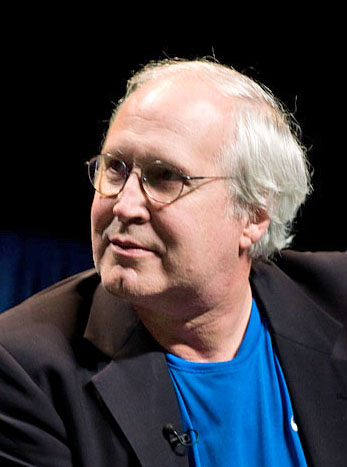

Chevy Chase

View on Wikipedia

Cornelius Crane "Chevy" Chase (/ˈtʃɛvi/ ⓘ; born October 8, 1943) is an American comedian, actor, and writer. He became the breakout cast member in the first season of Saturday Night Live (1975–1976), where his recurring Weekend Update segment became a staple of the show. As both a performer and a writer on the series, he earned two Primetime Emmy Awards out of four nominations.

Key Information

After leaving Saturday Night Live early in its second season, he established himself as a leading man, starring in some of the most successful comedy films of the 1980s, starting with his Golden Globe-nominated role in the romantic comedy Foul Play (1978). Most famously, he portrayed Ty Webb in Caddyshack (1980), Clark Griswold in five National Lampoon's Vacation films, and Irwin "Fletch" Fletcher in Fletch (1985) and Fletch Lives (1989). He also starred in Seems Like Old Times (1980), Spies Like Us (1985), ¡Three Amigos! (1986), and Funny Farm (1989).

He has hosted the Academy Awards twice (1987 and 1988) and briefly had his own late-night talk show, The Chevy Chase Show (1993). Chase had a popularity resurgence with his role as Pierce Hawthorne on the NBC sitcom Community (2009–2014).

Early life and education

[edit]Family

[edit]Cornelius Crane Chase was born in Lower Manhattan on October 8, 1943,[2] and grew up in Woodstock, New York.[3] He has an older brother, Ned Jr.[4]

His father, Edward Tinsley "Ned" Chase (1919–2005),[5] was a Princeton-educated Manhattan book editor and magazine writer.[6] Chase's paternal grandfather was artist and illustrator Edward Leigh Chase, and his great-uncle was painter and teacher Frank Swift Chase. His mother, Cathalene Parker (née Browning; 1923–2005), was a concert pianist and librettist, whose father, Rear Admiral Miles Browning, served as Admiral Raymond A. Spruance's Chief of Staff on the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise at the Battle of Midway in World War II. Cathalene was adopted as a child by her stepfather, Cornelius Vanderbilt Crane, heir to The Crane Company, and took the name Catherine Crane.[7] Her mother, also named Cathalene, was an opera singer who performed several times at Carnegie Hall.[8]

Chase was named for his adoptive grandfather, Cornelius, while the nickname "Chevy" was bestowed by his grandmother from the medieval English ballad "The Ballad of Chevy Chase". As a descendant of the Scottish Clan Douglas, she thought the name appropriate.[9]

According to his step-brother John:

[Chevy] once told me that people who defined themselves in terms of their ancestry were like potatoes—the best parts of them were underground. He disdained the pretension of his mother's side of the family, as embodied by her mother, Cattie.[9]

Early life

[edit]As a child, Chase vacationed at Castle Hill, the Cranes' summer estate in Ipswich, Massachusetts.[10] Chase's parents divorced when he was four; his father remarried into the Folgers coffee family, and his mother remarried twice. He has stated that he grew up in an upper middle class environment and that his adoptive maternal grandfather did not bequeath any assets to Chase's mother when he died.[11] In a 2007 biography, Chase stated that he was physically and psychologically abused as a child by his mother and stepfather, Dr. John Cederquist, a psychoanalyst.[12] In that biography, he said, "I lived in fear all the time, deathly fear." Abuse he was subjected to as a child included being awakened in the middle of the night by his mother to be slapped repeatedly across the face, lashes to the backs of his legs, punches to the head by his stepfather, and being locked in a bedroom closet for hours. As a punishment for being suspended from school at the age of 14, Chase was locked in a basement for several days.[13] Both of his parents died in 2005.[14]

Chase was educated at Riverdale Country School,[15] an independent day school in the Riverdale neighborhood of The Bronx, New York City, before being expelled. He ultimately graduated as valedictorian in 1962 from the Stockbridge School,[16] an independent boarding school in the town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. At Stockbridge, he was known as a practical joker with an occasional mean streak. He attended Haverford College during the 1962–1963 term, where he was noted for slapstick comedy and an absurd sense of physical humor, including his signature pratfalls and "sticking forks into his orifices".[17] During a 2009 interview on the Today show, he ostensibly verified the oft-publicized urban legend that he was expelled for harboring a cow in his fourth floor room,[18] although his former roommate David Felsen asserted in a 2003 interview that Chase left for academic reasons.[17] Chase transferred to Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, where he studied a pre-med curriculum and graduated in 1967 with a Bachelor of Arts in English.[19]

Chase did not enter medical school, which meant he was subject to the military draft. Chase was not drafted, and when he appeared in January 1989 as the first guest of the just-launched late-night The Pat Sajak Show, he said he had tricked his draft board into believing he deserved a 4-F classification by falsely claiming that he had "homosexual tendencies".[20]

While at Bard, Chase played drums in a band called The Leather Canary. The other two members, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, went on to found Steely Dan.[21] He also played drums and keyboards for a band called Chamaeleon Church, which recorded one album for MGM Records before disbanding.

Career

[edit]1967–1974: Early career

[edit]Chase was a member of an early underground comedy ensemble called Channel One, which he co-founded in 1967. He also wrote a one-page spoof of Mission: Impossible for Mad magazine in 1970 and was a writer for the short-lived Smothers Brothers TV show comeback in the spring of 1975. Chase made the move to comedy as a full-time career by 1973, when he became a writer and cast member of The National Lampoon Radio Hour, a syndicated satirical radio series. The National Lampoon Radio Hour also featured John Belushi, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, and Brian Doyle-Murray, all of whom later became the "Not-Ready-For-Prime Time Players" on NBC Saturday Night (later re-titled NBC's Saturday Night and finally Saturday Night Live). Chase and Belushi also appeared in National Lampoon's off-Broadway revue Lemmings, a sketch and musical send-up of popular youth culture, in which Chase also played the drums and piano during the musical numbers. He appeared in the movie The Groove Tube (1974), which was directed by another co-founder of Channel One, Ken Shapiro, featuring several Channel One sketches.[citation needed]

1975–1976: Saturday Night Live

[edit]

Chase was one of the original cast members of Saturday Night Live (SNL), NBC's late-night comedy television show, beginning in October 1975. During the first season, he introduced every show except two, with "Live from New York, it's Saturday Night!" The remark was often preceded by a pratfall, known as "The Fall of the Week". Chase became known for his skill at physical comedy. In one comedy sketch, he mimicked a real-life incident in which President Gerald Ford accidentally tripped while disembarking from Air Force One in Salzburg, Austria.[22][23] This portrayal of President Ford as a bumbling klutz became a favorite device of Chase's, and helped form the popular concept of Ford as being a clumsy man despite Ford having been a "star athlete" during his university years.[24] In later years, Chase met and became friendly with President Ford.[24][25]

Chase was the original anchor for the Weekend Update segment of SNL, and his catchphrase introduction, "I'm Chevy Chase… and you're not" became well known. His trademark conclusion, "Good night, and have a pleasant tomorrow" was later resurrected by Jane Curtin and Tina Fey. Chase also wrote comedy material for Weekend Update. For example, he wrote and performed "The News for the Hard of Hearing". In this skit, Chase read the top story of the day, aided by Garrett Morris, who repeated the story by loudly shouting it. Chase claimed that his version of Weekend Update was the inspiration for later news satire shows such as The Daily Show and The Colbert Report.[26] Weekend Update was later revived as a segment on The Chevy Chase Show,[27] a short-lived late-night talk show produced by Chase and broadcast by Fox Broadcasting Company.

Chase was committed contractually to SNL for only one year as a writer and became a cast member during rehearsals just before the show's premiere. He received two Emmy Awards and a Golden Globe Award for his comedy writing and live comic acting on the show. In Rolling Stone's February 2015 appraisal of all 141 SNL cast members to date, Chase was ranked tenth in overall importance. "Strange as it sounds, Chase might be the most under-rated SNL player," they wrote. "It took him only one season to define the franchise…without that deadpan arrogance, the whole SNL style of humor would fall flat."[28]

In a 1975 New York magazine cover story, which called him "The funniest man in America", NBC executives referred to Chase as "The first real potential successor to Johnny Carson" and claimed he would begin guest-hosting The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson within six months of the article. Chase dismissed rumors that he could be the next Carson by telling New York, "I'd never be tied down for five years interviewing TV personalities." Chase did not appear on the program until May 4, 1977, when he was promoting a prime-time special for NBC. Carson (who was never a fan of SNL) later said of Chase: "He couldn't ad-lib a fart after a baked-bean dinner."[29]

Chase acknowledged Ernie Kovacs's influence on his work in Saturday Night Live,[30] and he thanked Kovacs during his acceptance speech for his Emmy Award.[31] In addition, Chase spoke of Kovacs's influence on his work in an appearance in the 1982 documentary called Ernie Kovacs: Television's Original Genius.[citation needed]

1976–1989: Film stardom and acclaim

[edit]

In late 1976, in the middle of SNL's second season, Chase became the second member of the original cast to leave the show (after George Coe during the first season). While he landed starring roles in several films on the strength of his SNL fame, he asserted that the principal reason for his departure was the reluctance of his girlfriend, Jacqueline Carlin, to move to New York.[32] Chase moved to Los Angeles, married Carlin, and was replaced by Bill Murray, although he made a few cameo appearances on the show during the second season.

Chase hosted SNL eight times from 1978 to 1997.[33] In regard to Chase's 1997 appearance as a host, SNL creator and show-runner Lorne Michaels disputed reports that he was shocked by Chase's behavior or had banned him as a result, claims which he calls "idiotic".[34] While Chase has not returned to SNL to host since 1997, he appeared on the show's 25th anniversary special in 1999 and was interviewed for a 2005 NBC special on the first five years of SNL. Later appearances included a Caddyshack skit featuring Bill Murray, a 1997 episode with guest host Chris Farley, as the Land Shark in a Weekend Update segment in 2001, another Weekend Update segment in 2007, and in Justin Timberlake's monologue in 2013 as a member of the Five-Timers Club, where he was reunited with his Three Amigos co-stars Steve Martin and Martin Short. He also participated in the 40th anniversary special in February 2015.[35]

Chase's early film roles included Tunnel Vision (1976); Foul Play (1978, a box-office hit that made more than $44 million[36] and earned Chase a Golden Globe nomination); and Oh! Heavenly Dog (1980). The role of Eric "Otter" Stratton in National Lampoon's Animal House was written with Chase in mind, but he turned the role down to work on Foul Play.[11] The role went to Tim Matheson instead. Chase said in an interview that he chose to do Foul Play so he could do "real acting" for the first time in his career instead of just "schtick".[37]

Chase followed Foul Play in 1980 by portraying Ty Webb in the Harold Ramis comedy Caddyshack. A major box office success that pulled in $39 million off a $6 million budget,[38] the movie has become a classic. It reached a 73% approval rate on Rotten Tomatoes, with critics saying: "Though unabashedly crude and juvenile, Caddyshack nevertheless scores with its classic slapstick, unforgettable characters, and endlessly quotable dialogue".[39] That same year, he reunited with Foul Play co-star Goldie Hawn for Neil Simon's Seems Like Old Times, a box-office success that earned more than $43 million.[40] He then released a self-titled record album, co-produced by Chase and Tom Scott, with novelty and cover versions of songs by Randy Newman, Barry White, Bob Marley, the Beatles, Donna Summer, Tennessee Ernie Ford, The Troggs, and The Sugarhill Gang.

Chase narrowly escaped death by electrocution during the filming of Modern Problems in 1980. During a sequence in which Chase's character wears "landing lights" as he dreams that he is an airplane, the lights malfunctioned and an electric current passed through Chase's arm, back, and neck muscles. The near-death experience followed the end of his marriage to Carlin, and Chase experienced a period of deep depression. He married Jayni Luke in 1982. Chase continued his film career by playing Clark Griswold in 1983's National Lampoon's Vacation. Directed by Ramis and written by John Hughes, the movie grossed $61 million[41] on a $15 million budget—his most successful movie at the time.

In 1985, Chase played Irwin "Fletch" Fletcher in Fletch, based on Gregory Mcdonald's Fletch books, which grossed more than $50 million off an $8 million budget.[42] That same year, he appeared in a sequel to Vacation, National Lampoon's European Vacation, which pulled in just shy of $50 million at the box office,[43] and co-starred with fellow SNL alum Dan Aykroyd in Spies Like Us, which made $60 million.[44] In 1986, Chase joined SNL veterans Steve Martin and Martin Short in the Lorne Michaels–produced comedy ¡Three Amigos! that made nearly $40 million,[45] with Chase declaring in an interview that making Three Amigos was the most fun he had making a film.[46] He also appeared alongside Paul Simon, one of his best friends, in Simon's 1986 second video for "You Can Call Me Al", in which he lip-syncs all of Simon's lyrics.[47]

In 1987, his Cornelius Productions company signed a non-exclusive, first-refusal deal to develop four feature projects at the Warner Bros. studio, and set up a fifth project at Universal Pictures.[48] Chase hosted the Academy Awards in 1987 and 1988, opening the telecast in 1988 with the quip, "Good evening, Hollywood phonies!" In 1988, he starred alongside Madolyn Smith in Funny Farm, a sizeable hit at $25 million[49] that reached 64% approval rate on Rotten Tomatoes.[50] That same year, he appeared (albeit via a glorified cameo) in a sequel to Caddyshack, Caddyshack II, which made less than $12 million,[51] becoming one of his few flops at the time.[52]

In 1989, Chase starred in a sequel to Fletch, Fletch Lives, which went on to gross more than $35 million,[53] and made a third Vacation film, National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation, which pulled in $71 million and, thanks to its holiday theme, has become one of his more durable films.[54] At the height of his career in the late 1980s, Chase earned around US$7 million per film and was a highly visible celebrity.

1990–2009: Career fluctuations

[edit]Chase played saxophone onstage at Simon's free concert at the Great Lawn in Central Park in the summer of 1991. Later in 1991, he helped record and appeared in the music video "Voices That Care" to entertain and support U.S. troops involved in Operation Desert Storm, and supported the International Red Cross. Chase had three consecutive film flops: Razzie Award-nominated Nothing but Trouble (1991), Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992), and Cops & Robbersons (1994). The three releases had a combined gross of $34 million in the United States.

In September 1993, Chase hosted The Chevy Chase Show, a weeknight talk show, for the Fox Broadcasting Company. Although it had high commercial expectations, the show was cancelled by Fox after five weeks. Chase later appeared in a commercial for Doritos, airing during the Super Bowl, in which he made humorous reference to the show's failure.[55]

Chase found success with some of his subsequent movies. Man of the House (1995), co-starring Farrah Fawcett, was relatively successful, grossing $40 million,[56] and Vegas Vacation (1997, his fourth Vacation film) was a box office success, grossing $36.4 million.[57] Snow Day (2000), in which Chase appeared, was also successful grossing over $60 million,[58] as well as Orange County (2002), grossing more than $40 million.[59] Chase was Hasty Pudding's 1993 Man of the Year, and received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in that same year.[14] He also received The Harvard Lampoon's Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996. In 1998, a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs, California, Walk of Stars was dedicated to him.[60]

He was roasted by the New York Friars Club for a Comedy Central television special in 2002. This roast was noted for being unusually vitriolic, even by the standards of a roast.[61] Some of the more recent films starring Chase (e.g., Vacuums, Rent-a-Husband, Goose!) have not been widely released in the United States. He returned to mainstream movie-making in 2006, co-starring with Tim Allen and Courteney Cox in the comedy Zoom, though it was both a critical and commercial failure. Chase guest-starred as an anti-Semitic murder suspect in "In Vino Veritas", the November 3, 2006, episode of Law & Order. He also guest-starred in the ABC drama series Brothers & Sisters in two episodes as a former love interest of Sally Field's character. Chase appeared in a prominent recurring role as villainous software magnate Ted Roark on the NBC spy-comedy Chuck. In 2009, Chase and Dan Aykroyd voiced themselves in the Family Guy episode "Spies Reminiscent of Us".

2009–2014: Return to television

[edit]Starting in 2009, Chase returned to NBC in the sitcom Community, as aging moist-towelette tycoon Pierce Hawthorne. The show was created by Dan Harmon and starred Joel McHale, Alison Brie, Gillian Jacobs, Donald Glover, Danny Pudi, and Yvette Nicole Brown. The series received critical acclaim for its acting and writing, appeared on numerous critics' year-end "best-of" lists and developed a cult following.[62][63] The New York Times critic Alessandra Stanley praised the casting of Chase writing, "Jeff has the kind of sardonic repartee and slapdash nonchalance that the comedian Chevy Chase had when he was the young star of the Fletch movies", while adding, "Even that is an inside casting joke: Mr. Chase, who is farcically loopy and delightful in the pilot."[64]

In 2010, Chase appeared in an online Vacation short film Hotel Hell Vacation, featuring the Griswold parents, and in the Funny or Die original comedy sketch "Presidential Reunion", where he played President Ford alongside other current and former SNL president impersonators. That same year, Chase appeared in the film Hot Tub Time Machine which received some praise,[65][66] and a sequel.

Throughout the filming of Community, Chase became increasingly uncomfortable with the direction of Pierce's character arc. It was reported that in 2012 Chase had an outburst on set yelling if it continued he may be asked to call either Donald Glover or Yvette Nicole Brown's character the N-word. Chase later apologized for the outburst.[67][68] Soon after his apology, Chase left the show[69][70] due to increasing disagreements with his character and the show's creator Dan Harmon. After a mutual agreement with the network, his character was abruptly written out of the fourth season of Community.[69] Chase later claimed that his exit was due to his personal opinions of the show rather than the outburst, claiming that it "wasn't funny enough".[71] His departure was cemented by the writers, who killed off Pierce in the third episode of Community's fifth season.[72]

2015–present

[edit]In 2015, Chase reprised his role as Clark Griswold in the fifth Vacation installment, titled Vacation. Unlike the previous four films in which Clark is the main protagonist, he only has a brief though pivotal cameo appearance.[73] In spite of largely negative critical reception,[74] the film proved to be a financial success, grossing over $107 million worldwide.[75]

In 2019, Chase was in the Netflix movie The Last Laugh where he starred alongside Richard Dreyfuss.

In 2024, he starred in the film The Christmas Letter with Randy Quaid and Brian Doyle-Murray.[76]

Personal life

[edit]

Marriage and family

[edit]Chase married Susan Hewitt in New York City on February 23, 1973.[citation needed] They divorced on February 1, 1976. His second marriage, to Jacqueline Carlin, was formalized on December 4, 1976, and ended in divorce on November 14, 1980; they had no children.[77]

Chase resided in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles from 1980 until 1995 in a Tudor-style home. He was the Honorary Mayor of Pacific Palisades between 1986 and 1988.[78][79]

He married his third wife, Jayni Luke, in Pacific Palisades on June 19, 1982.[80] They have three daughters: Cydney, Caley, and Emily.[4] The couple reside in Bedford, New York.[81]

Substance abuse

[edit]In 1986, Chase was admitted to the Betty Ford Center for treatment of a prescription painkiller addiction. His use began after he experienced ongoing back pain related to the pratfalls he took during his Saturday Night Live appearances.[82] In 2010, he said that his drug abuse had been "low level."[83]

He entered the Hazelden Clinic in September 2016 to receive treatment for alcoholism.[84]

Political views

[edit]An active environmentalist and philanthropist, Chase is a political liberal. He campaigned for Democratic presidential nominees Bill Clinton in the 1990s, and John Kerry in 2004.[85][86]

In 2004, during a speech at a People for the American Way benefit at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts he mocked Republican President George W. Bush, Kerry's opponent in the 2004 election, referring to Bush as an "uneducated, real lying schmuck" and a "dumb fuck". His comments upset both the organizers and the crowd.[87]

He endorsed Hillary Clinton's 2008 presidential campaign.[88]

Fight with Bill Murray

[edit]While filming an episode of Saturday Night Live in 1978, Chase got into a fistfight with Bill Murray in John Belushi's dressing room. Murray and Chase's backstage brawl took place when Chase returned to host the show after his exit as a full-time cast member in 1976. Murray had reportedly made a derogatory comment about Chase's troubled marriage to Jacqueline Carlin, leading Chase to criticize Murray's physical appearance. The fight was witnessed by cast members Jane Curtin, Laraine Newman, and Gilda Radner.[89]

In a talk show appearance in 2021, Newman noted of the altercation, "it was very sad and painful and awful". She went on to say, "I think they both knew the one thing that they could say to one another that would hurt the most and that's what I think incited it." Chase and Murray would later reconcile to star together in Caddyshack in 1980.[90]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Walk... Don't Walk | Pedestrian | Short film |

| 1974 | The Groove Tube | The Fingers/Geritan/Four Leaf Clover | |

| 1976 | Tunnel Vision | Himself | |

| 1978 | Foul Play | Tony Carlson | |

| 1980 | Oh! Heavenly Dog | Browning | |

| Caddyshack | Ty Webb | ||

| Seems Like Old Times | Nicholas Gardenia | ||

| 1981 | Under the Rainbow | Bruce Thorpe | |

| Modern Problems | Max Fiedler | ||

| 1983 | National Lampoon's Vacation | Clark Griswold | |

| Deal of the Century | Eddie Muntz | ||

| 1985 | Fletch | Irwin 'Fletch' Fletcher | |

| National Lampoon's European Vacation | Clark Griswold | ||

| Sesame Street Presents: Follow That Bird | Newscaster | Cameo | |

| Spies Like Us | Emmett Fitz-Hume | ||

| 1986 | ¡Three Amigos! | Dusty Bottoms | |

| 1988 | The Couch Trip | Condom Father | Cameo |

| Funny Farm | Andy Farmer | ||

| Caddyshack II | Ty Webb | ||

| 1989 | Fletch Lives | Irwin 'Fletch' Fletcher | |

| National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation | Clark "Sparky" Griswold | ||

| 1991 | Nothing but Trouble | Chris Thorne | |

| L.A. Story | Carlo Christopher | Cameo | |

| 1992 | Memoirs of an Invisible Man | Nick Halloway | |

| Hero | Deke | Uncredited | |

| 1993 | Last Action Hero | Himself | Cameo |

| 1994 | A Century of Cinema | Documentary | |

| Cops & Robbersons | Norman Robberson | ||

| 1995 | Man of the House | Jack Sturgess | |

| 1997 | Vegas Vacation | Clark Griswold | |

| 1998 | Dirty Work | Dr. Farthing | |

| 2000 | Snow Day | Tom Brandston | |

| Pete's Pizza | Narrator | Voice; Short film | |

| The One Armed Bandit | Cop | Short film | |

| 2002 | Orange County | Principal Harbert | |

| 2003 | Vacuums | Mr. Punch | |

| Bitter Jester | Himself | Darren Watkins | |

| 2004 | Our Italian Husband | Paul Parmesan | |

| Bad Meat | Congressman Bernard P. Greely | Direct-to-DVD | |

| 2005 | Ellie Parker | Dennis Swartzbaum | |

| 2006 | Funny Money | Henry Perkins | |

| Doogal | Train | Voice | |

| Goose on the Loose | Congreve Maddox | Direct-to-DVD | |

| Zoom | Dr. Grant | ||

| 2007 | Cutlass | Stan | Short film[91] |

| 2009 | Stay Cool | Principal Marshall | |

| Jack and the Beanstalk | Antipode | ||

| 2010 | Hot Tub Time Machine | Repairman | |

| Hotel Hell Vacation | Clark Griswold | Short film | |

| 2011 | Not Another Not Another Movie | Max Storm | |

| 2013 | Before I Sleep | Gravedigger | |

| 2014 | Lovesick | Lester | |

| Shelby | Grandpa Geoffrey | Direct-to-DVD | |

| 2015 | Hot Tub Time Machine 2 | Repairman | |

| Vacation | Clark Griswold | ||

| 2017 | The Last Movie Star | Sonny | |

| Hedgehogs | ThinkMan | Voice; Direct-to-DVD | |

| 2019 | The Last Laugh | Al Hart | |

| 2020 | The Very Excellent Mr. Dundee | Chevy | |

| 2021 | Panda vs. Aliens | King Karoth | Voice; Direct-to-DVD |

| 2023 | Zombie Town | Mezmarian | |

| Glisten and the Merry Mission | Santa Claus | Voice | |

| 2024 | The Christmas Letter | Norm De Plume |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | The Smothers Brothers Show | Writer | |

| 1975–2025 | Saturday Night Live | Various characters / Himself (host) | 39 episodes; also writer; 8 episodes |

| 1977 | The Chevy Chase Show | Himself | Television special; also writer |

| The Paul Simon Special | |||

| 1979 | The Chevy Chase National Humor Test | ||

| 1987 | 59th Academy Awards | Himself (co-host) | Television special |

| 1988 | 60th Academy Awards | Himself (host) | |

| Untitled Dan Aykroyd Project | Adin A. Oss | Pilot | |

| 1990 | The Earth Day Special | Vic's Buddy | Television special |

| 1993 | The Chevy Chase Show | Himself (host) | 25 episodes; also writer and producer |

| 1995 | The Larry Sanders Show | Himself | Episode: "Roseanne's Return" |

| 1997 | The Nanny | Episode: "A Decent Proposal" | |

| 2002 | America's Most Terrible Things | Andy Potts | Pilot |

| 2003 | Freedom: A History of US | Various characters | 5 episodes |

| 2004 | The Karate Dog | Cho-Cho | Voice; Television film |

| 2006 | The Secret Policeman's Ball | General Nuisance | Television special |

| Law & Order | Mitch Carroll | Episode: "In Vino Veritas" | |

| 2007, 2009 | Family Guy | Clark Griswold / Himself (voices) | Episodes: "Blue Harvest" "Spies Reminiscent of Us" |

| 2007 | Brothers & Sisters | Stan Harris | 2 episodes |

| 2009 | Hjälp! | Dan Carter | 8 episodes |

| Chuck | Ted Roark | 3 episodes | |

| 2009–2014 | Community | Pierce Hawthorne | 83 episodes |

| 2014 | Hot in Cleveland | Ross | Episode: "People Feeding People" |

| Wishin' and Hopin' | Adult Felix (voice) | Television film | |

| 2015 | Chevy | Chase | Pilot |

| 2016 | A Christmas in Vermont | Preston Bullock | Television film |

Awards and nominations

[edit]In 1976, he was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Awards for "Writing for a Variety Series" as part of The Smothers Brothers Show's writers room.[citation needed] Also in 1976 he was nominated at the Primetime Emmy Awards for his work on the first season of Saturday Night Live. He won both nominations.[92]

On September 23, 1993, Chase received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7021 Hollywood Boulevard.[14]

| Award | Year[a] | Category | Title | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writers Guild of America Awards | 1976 | Writing for a Variety Series | The Smothers Brothers Show | Nominated | |

| Primetime Emmy Awards | 1976 | Individual Performance in a Variety Program | Saturday Night Live | Won | [92] |

| Outstanding Writing for a Variety Series | Won | ||||

| 1977 | Individual Performance in a Variety Program | Nominated | |||

| Outstanding Writing for a Variety Series | Nominated | ||||

| 1978 | Outstanding Writing for a Variety Special | The Paul Simon Special | Won | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | 1978 | Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy | Foul Play | Nominated | [93] |

| New Star of the Year | — | Nominated | |||

| Saturn Awards | 1992 | Best Actor | Memoirs of an Invisible Man | Nominated | [94] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Year refers to when the ceremony took place.

References

[edit]- ^ "Famous birthdays for Oct. 8: Bella Thorne, Chevy Chase". UPI. October 8, 2022. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Chevy Chase biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ "Is Chevy Chase a Potential Successor to Johnny Carson?". New York Magazine. June 26, 2008. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ a b "Chevy Chase is 74, sober and ready to work. The problem? Nobody wants to work with him". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Edward Chase, 86, Longtime Book Editor, Is Dead (Published 2005)". The New York Times. June 17, 2005. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Edward Tinsley Chase '41 | Princeton Alumni Weekly". Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Explorer's Survivor Omitted". The New York Times. July 11, 1962. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Martha Burgin; Maureen Holtz (2009). Robert Allerton: the private man & the public gifts. The News-Gazette. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-9798420-7-8.

- ^ a b Fruchter, Rena. I'm Chevy Chase...and You're Not. Virgin Books, 2007.

- ^ "New York Magazine". Newyorkmetro.com. August 23, 1993. p. 32. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ a b Chase, Chevy, interview on Howard Stern Show, Sirius Satellite Radio, September 18, 2008.

- ^ "Chevy Chase says in book he was beaten by mother". Reuters. April 24, 2007. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Fruchter, Rena. I'm Chevy Chase and You're Not. London: Virgin Books Ltd., 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Chevy Chase". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Jarvis, Jeff (September 12, 1983). "Chevy Chase's New High: Fatherhood". People. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Milwaukee Sentinel — Google News Archive Search". News.google.com. Retrieved December 30, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Rudolph, Stephanie. "Prankly Speaking". The Bi-College News. October 28, 2003. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "blogs.haverford.edu". blogs.haverford.edu. October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on March 6, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Movies and Shows". Apple TV. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Late-Night Chitchat Additions: Pat Sajak and Arsenio Hall Archived September 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, a January 11, 1989, review from The New York Times

- ^ Brunner, Rob (March 17, 2006). "The origins of Steely Dan". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 10, 2025.

- ^ Cannon, Lou (December 27, 2006). "Gerald R. Ford" (Obituary). The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Chawkins, Steve (October 25, 2005). "Bush's Tribute to a Lofty Symbol". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ a b "Chevy Chase recalls Ford as 'a terrific guy': 'SNL' comedian became famous in the '70s portraying president as klutz". Today.com. December 27, 2006. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Chase, Chevy (January 6, 2007). "Mr. Ford Gets the Last Laugh". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Keller, Joel (April 16, 2007). "A delusional Chevy Chase says he created The Daily Show". AOL TV. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

[...] asked what he thought of Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, [Chase] took credit for their success. "[I] think that, you know, I started it with my Weekend Update," he responds, implying that the ideas for both The Daily Show and The Colbert Report came directly from WU.

- ^ Carter, Bill (July 13, 1993). "With Pratfalls, Chevy Chase's Plans For Late-Night TV". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ Rolling Stone, issue 1229, February 26, 2015, p. 32.

- ^ "The 25 Meanest Things Ever Said by Men". Menshealth.com. June 25, 2011. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Chevy Chase, "The Unique Comedy of Ernie Kovacs", TV Guide, April 9, 1977, p. 39–40.

- ^ Hofer, Stephen F.(2006). TV Guide: the official collector's guide, Bangzoom Publishers.

- ^ "Live From New York: The First 5 Years of Saturday Night Live". Saturday Night Live. February 20, 2005. NBC.

- ^ "The Saturday Night Live Season 2 Cast: Live from New York, It's Bill Murray". NBC Insider. January 5, 2024. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (September 19, 2018). "Chevy Chase can't change". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ McCoy, Terrence (February 17, 2015). "Chevy Chase, Too Mean To Succeed". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Foul Play". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Shales, Tom. Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live. Back Bay Books, 2003.

- ^ "Caddyshack". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Caddyshack (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2024.

- ^ "Seems Like Old Times". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "National Lampoon's Vacation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Fletch". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "National Lampoon's European Vacation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Spies Like Us". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 15, 2024.

- ^ "Three Amigos!". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Daniel Fierman (August 13, 2004). "Chevy Chase reflects on his best work". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Paul Simon - You Can Call Me al (Official Video)". YouTube. June 16, 2011.

- ^ Tusher, Will (May 27, 1987). "Chevy Chase's Cornelius Prods. Lines Up Projects With WB, U". Variety. p. 28.

- ^ "Funny Farm". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 27, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Funny Farm (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ "Caddyshack II". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (July 24, 2020). "The Inside Story of Caddyshack II". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Fletch Lives". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 3, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "1994 Doritos advert". YouTube. August 31, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ "Man of the House". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Vegas Vacation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Snow Day". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Orange County". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ "Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated" (PDF). Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ Heffernan, Virginia (December 2, 2002). "Chevy Chase, Humiliated Again". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Community was one of the most inventive shows in TV history". Vox. September 20, 2019. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "The Meta, Innovative Genius of Community". The Atlantic. May 12, 2011. Archived from the original on April 5, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (September 16, 2009). "A Wink at Colleges and a Nod to Clichés". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Fernandez, Jay A. (May 28, 2009). "Chevy Chase jumps in Hot Tub". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "Hot Tub Time Machine Film Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 30, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Drops N-Word In Tirade On The Set Of 'Community'". Deadline Hollywood. October 20, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Sharf, Zach (February 15, 2022). "'Chevy Chase Ignores Claims of Problematic Set Behavior: 'I Don't Give a Crap...I Am Who I Am'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Sharf, Zach (February 15, 2022). "'Chevy Chase Ignores Claims of Problematic Set Behavior: 'I Don't Give a Crap...I Am Who I Am'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2023.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Drops N-Word In Tirade On The Set Of 'Community'". Deadline Hollywood. October 20, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Claims 'Community' Just "Wasn't Funny Enough" for Him". Vanity Fair. September 26, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Hedash, Kara (March 6, 2020). "Community: The Reason Why Chevy Chase Left Before Season 5". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on November 22, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ "The Chevy Chase 'Vacation' Cameo Is A Hilarious Throwback To The Griswolds Of The Original Franchise". Bustle. July 31, 2015. Archived from the original on January 13, 2025. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Vacation". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Vacation". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (May 30, 2024). "Comedy 'The Christmas Letter' Starring Chevy Chase, Randy Quaid Acquired By Scatena & Rosner Films". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 10, 2025.

- ^ "Obituary: Jacqueline Carlin Melcher 1942–2021". Bermudez Family. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Hunts Buyer for Home / Comedian wants to leave L.A." April 12, 1995.

- ^ "Honorary Mayors". Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Gelder, Lawrence Van (October 15, 1982). "At the Movies (Published 1982)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Hermit Hell! Chevy Chase Living Like A Loner: 'He's Alienated Himself From Everyone'". RadarOnline. February 15, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Being Treated For Addiction to Painkillers". The New York Times. October 12, 1986. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ Fussman, Cal (September 23, 2010). "Chevy Chase: What I've Learned". Esquire. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (September 6, 2016). "Chevy Chase enters rehab". CNN. Archived from the original on September 6, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ White, Mark, ed. (May 15, 2012). The Presidency of Bill Clinton: The Legacy of a New Domestic and Foreign Policy. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. p. 239. ISBN 9780857722478.

- ^ "Stars Raise Voices Against Bush". Los Angeles Times. July 9, 2004. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ Leiby, Richard (December 16, 2004). "It's the F-Time Show With Chevy Chase". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ Staff, The Hill (April 16, 2007). "Hugh Hefner gives $2,300 to Clinton's '08 campaign". The Hill. Archived from the original on June 11, 2025. Retrieved July 9, 2025.

- ^ "It's Saturday Night!". Vanity Fair. June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ Roberto, Melissa (June 18, 2021). "Bill Murray and Chevy Chase's backstage fight at 'SNL' was 'painful' to watch, show alums say". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Cutlass". Tribeca. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ a b "Chevy Chase". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Globe Awards for 'Chevy Chase'". Golden Globes. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ "Memoirs of an Invisible Man". TV Guide. Retrieved December 24, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- I'm Chevy Chase...and You're Not (The Authorized Biography) by Rena Fruchter. Virgin Books, 2007. ISBN 1-85227-346-1.

- Who's Who in Comedy by Ronald L. Smith. Pp. 102–103. New York: Facts on File, 1992. ISBN 0-8160-2338-7.

- Live from New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live by Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller. Back Bay Books.

External links

[edit]Chevy Chase

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Family Background

Cornelius Crane Chase, known professionally as Chevy Chase, was born on October 8, 1943, in Lower Manhattan, New York City, to Edward Tinsley "Ned" Chase and Cathalene Parker Browning.[2] His father, Edward Tinsley Chase (1919–2005), worked as a prominent book editor and magazine writer in Manhattan, with a background tied to artistic and publishing circles; Edward Leigh Chase, his paternal grandfather, was a landscape and equine artist.[10] [11] Chase's mother, Cathalene (1923–2005), was a concert pianist and librettist whose own mother had performed as an opera singer at Carnegie Hall; as a child, Cathalene was adopted by her stepfather, Cornelius Vanderbilt Crane—heir to the Crane Company plumbing fortune—and took his surname, though he later disinherited her after divorcing her mother in 1940.[2] [12] Chase's parents divorced when he was four years old, after which his father remarried Ethelyn Atha, connecting the family to the Folgers coffee lineage through her background, while his mother remarried twice, first to someone leading to half-siblings Pamela and John Cederquist, and later to actor James Widdoes, producing additional half-sibling Catherine.[13] [14] From his parents' marriage, Chase had an older brother, Edward Tinsley Chase Jr. (known as Ned Jr.), and a sister, Cynthia Chase, both of whom pursued academic and professional paths, with Cynthia becoming a professor.[2] [15] Chase was named Cornelius Crane in honor of his maternal adoptive grandfather, reflecting the family's ties to established American industrial and artistic lineages despite the parental split's disruptions.Childhood and Formative Experiences

Cornelius Crane Chase, later known as Chevy Chase, was born on October 8, 1943, in Lower Manhattan, New York City, to Edward Tinsley "Ned" Chase, a book editor and magazine writer, and Cathalene Parker Browning, a concert pianist and librettist.[2] His paternal grandmother bestowed the nickname "Chevy," reportedly inspired by the affluent suburb of Chevy Chase, Maryland, or the medieval ballad of the same name.[1] Chase's parents divorced when he was four years old, around 1947; he was primarily raised by his mother, who remarried, while his father wed Lyn Atha, an heiress to the Folger coffee fortune.[16] [17] Chase has recounted severe physical and emotional abuse during this period, primarily from his mother and stepfather John Cederquist, including beatings with a hairbrush, being slapped awake at night, and prolonged confinement in closets or basements.[18] [19] These incidents, detailed in his 2007 authorized biography I'm Chevy Chase... and You're Not, left him living in "deathly fear" with low self-esteem, hindering academic focus despite a high IQ and resulting in poor early grades that prompted further punishment.[20] The abuse reportedly ceased around age 15 following a confrontation with his mother.[16] Growing up in a New York City neighborhood on the edge of Spanish Harlem near Park Avenue, Chase, as a crew-cut white child in the 1950s, frequently encountered hostility from local youths, leading to regular fights and chases.[21] He described being punched in the face multiple times and once stabbed three times in the back while fleeing an attacker, scars from which he still bears; these encounters taught him self-defense tactics, such as using headlocks or escaping on roller skates down Park Avenue.[21] Amid a musically inclined family—his mother a pianist and his grandmother an opera singer—Chase developed perfect pitch, though he characterized himself as a "naughty boy" who explored alleyways and embraced minor mischief in the city's "concrete canyon" environment.[21] These formative adversities, combining familial trauma with street-level violence, contributed to a childhood marked by resilience forged through repeated conflict.[18][21]Academic Pursuits

Chase completed his secondary education at Stockbridge School, an independent boarding school in Massachusetts, graduating as valedictorian in 1962.[22][23] Following high school, he enrolled at Haverford College, attending from 1962 to 1963.[3] He subsequently transferred to Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.[1] At Bard College, Chase pursued a Bachelor of Arts degree in English, which he received in 1968.[1][3] During his time there, he engaged in extracurricular activities including playing percussion in student bands, though his formal studies centered on literature rather than continuing an initial interest in pre-medical coursework reported in some accounts.[24] In recognition of his later career achievements, Bard College conferred upon him an honorary Doctor of Arts degree in 1989.[24]Early Career

Initial Forays in Comedy and Writing (1960s–1974)

Chase co-founded the underground comedy troupe Channel One in New York in 1967, where he performed in video sketches and improvisational pieces that satirized television formats.[3][23] The group, which included future collaborators like Ken Shapiro and Richard Belzer, focused on experimental, low-budget productions previewing cable-style parody content ahead of its mainstream rise.[25] Chase balanced these performances with day jobs such as truck driver, tennis instructor, and bartender to support himself during this period.[3] In 1970, Chase contributed his first published comedy writing with a one-page spoof titled "A TV Scene We'd Like to See: Mission: Impossible" in MAD magazine issue #134, illustrated by John Cullen Murphy.[26] This piece mocked the espionage series' improbable plots through exaggerated self-parody, marking an early foray into print satire that aligned with his emerging interest in deconstructing media tropes.[27] By 1973, Chase transitioned to comedy full-time, joining The National Lampoon Radio Hour as both writer and performer on the syndicated satirical program, which aired weekly sketches featuring emerging talents like John Belushi and Gilda Radner.[28] The show, an audio extension of National Lampoon magazine's irreverent humor, debuted that year and ran through 1974, honing Chase's skills in rapid-fire banter and character bits.[29] Channel One's work culminated in the 1974 independent film The Groove Tube, compiled from the troupe's sketches and directed by Shapiro, providing Chase with his screen debut in segments parodying news broadcasts and commercials.[1] The film's release that year showcased Chase's physical comedy and deadpan delivery, elements that would later define his breakthrough, though it received mixed reviews for its uneven execution typical of sketch compilations.[30]Breakthrough on Saturday Night Live (1975–1976)

Chevy Chase joined Saturday Night Live (SNL) as one of the original "Not Ready for Prime Time Players," debuting in the show's premiere episode on October 11, 1975, hosted by George Carlin.[31] His early contributions included anchoring the inaugural Weekend Update segment that same night, a mock news desk format conceived by head writer Herb Sargent to deliver satirical commentary on current events.[32] Chase's deadpan delivery and self-deprecating humor in Weekend Update quickly established him as the season's standout performer, with the segment appearing in nearly every episode of the 1975–1976 season.[33] Chase's breakthrough role extended beyond news parody to physical comedy, most notably his recurring impersonation of President Gerald Ford, which debuted in the cold open of the November 8, 1975, episode.[34] Rather than mimicking Ford's voice or mannerisms, Chase emphasized exaggerated pratfalls—tripping, stumbling, and falling repeatedly—to satirize media perceptions of the president's clumsiness following real-life incidents, such as Ford's stumble at the 1975 Salzburg Conference.[35] This approach, featuring Chase in a suit and tie repeatedly botching simple movements, resonated with audiences for its simplicity and visual punch, appearing in multiple sketches throughout the season, including "Ford on the Phone" addressing political pressures.[36] The Ford bits, combined with Chase's Weekend Update sign-off catchphrase "Good night, and have a pleasant tomorrow," amplified his visibility, making him SNL's first breakout star and earning him an Emmy nomination for writing in 1976.[37] By mid-season, Chase's popularity had surged, with his segments driving much of the show's early buzz and contributing to SNL's cultural impact amid competition from established late-night programming.[33] However, internal tensions arose from his ego and perceived favoritism by producer Lorne Michaels, though these did not immediately derail his tenure.[38] Chase remained through the full 24-episode first season, ending May 29, 1976, but departed shortly thereafter—contractually limited to one year—to pursue Hollywood opportunities, including a brief marriage to a Los Angeles woman he met during the run.[39] His exit created a void filled by Bill Murray, but Chase's SNL work laid the foundation for his film career, cementing physical comedy and ironic detachment as hallmarks of his persona.[38]Film Career Peak

Transition to Film and Early Successes (1976–1985)

Chase departed from Saturday Night Live as a cast member on October 30, 1976, during the show's second season, seeking opportunities in feature films after gaining national recognition from his television work.[38] His exit was motivated by lucrative movie offers and personal reasons, including a relocation prompted by a relationship.[40] Prior to this, he had appeared in minor roles, such as a cameo as himself in the 1976 satirical film Tunnelvision.[41] Chase's film breakthrough came with Foul Play in 1978, where he starred opposite Goldie Hawn as San Francisco police inspector Tony Carlson in a romantic thriller-comedy directed by Colin Higgins.[42] The film grossed approximately $40.4 million domestically, marking a commercial success and establishing Chase as a leading man in Hollywood comedies.[43] This role capitalized on his deadpan humor and physical comedy style honed on SNL, earning positive reception for his chemistry with Hawn.[44] In 1980, Chase portrayed Ty Webb, a laid-back, philosophical golf pro, in Caddyshack, directed by Harold Ramis.[45] Despite production challenges including improvisation and on-set excesses, the ensemble comedy resonated with audiences, achieving box office earnings and later cult status for its irreverent satire of country club culture.[46] Chase's performance as the zen-like mentor to the protagonist contributed to the film's enduring appeal among comedy fans.[47] The early 1980s saw mixed results with films like Oh Heavenly Dog (1980), Under the Rainbow (1981), and Modern Problems (1981), which underperformed commercially.[5] However, Chase rebounded with National Lampoon's Vacation in 1983, playing everyman father Clark Griswold in a road trip comedy scripted by John Hughes and again directed by Ramis.[48] The film's depiction of family mishaps during a cross-country drive to an amusement park grossed over $86 million worldwide, solidifying Chase's franchise potential. By 1985, he starred as investigative reporter Irwin "Fletch" Fletcher in the adaptation of Gregory McDonald's novel, delivering a fast-paced neo-noir comedy that highlighted his improvisational skills and earned a dedicated following.[49]Iconic Roles and Commercial Heights (1983–1989)

Chase solidified his status as a leading comedic actor during this period through a series of commercially successful films that capitalized on his deadpan physical comedy and everyman persona. His portrayal of Clark Griswold in the National Lampoon's Vacation series became one of his most enduring roles, beginning with the 1983 original, where he played a determined suburban father enduring a chaotic cross-country drive to Walley World. Released on July 29, 1983, the film grossed approximately $107 million worldwide on a modest budget, achieving financial success despite a 27% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes from critics who noted its irreverent humor but uneven execution.[50] This role showcased Chase's ability to blend slapstick mishaps with relatable family frustrations, grossing over $61 million domestically and spawning sequels that reinforced his box-office appeal.[51] The Vacation franchise continued with National Lampoon's European Vacation in 1985, again starring Chase as Griswold, this time navigating cultural blunders across Europe after winning a game show prize. Released on July 26, 1985, the sequel emphasized Chase's exasperated reactions to escalating absurdities, such as a folk dance brawl in Germany, and performed solidly at the box office as part of the series' moneymaking run, though specific grosses reflected a slight dip from the original amid broader 1980s comedy saturation.[52] Complementing this, Chase's turn as investigative reporter Irwin "Fletch" Fletcher in Fletch (1985) highlighted his improvisational wit in a satirical take on journalism and corruption. Premiering on May 31, 1985, with an $8 million budget, it earned $50.6 million domestically and $59.6 million worldwide, buoyed by Chase's chameleon-like disguises and rapid-fire one-liners adapted from Gregory Mcdonald's novels.[53] Critics praised it as a strong vehicle for his brand of sarcasm, earning a 79% Rotten Tomatoes score.[49] Further diversifying his portfolio, Three Amigos! (1986) paired Chase with Steve Martin and Martin Short as bumbling silent-film stars mistaken for real heroes in a Mexican village. In the role of Dusty Bottoms, Chase delivered vaudeville-style antics, including the film's signature synchronized salute, in a December 12, 1986, release directed by John Landis that grossed over $153 million worldwide against mixed reviews (45% on Rotten Tomatoes), cementing its status as a cult favorite for its ensemble chemistry rather than solo star power.[54] Chase closed the decade with Fletch Lives (1989), reprising the Fletcher character in a Southern Gothic sequel involving inheritance schemes, which opened to $8 million in its March debut and totaled around $56 million domestically, maintaining franchise viability but signaling early signs of audience fatigue with repetitive formulas.[55] These projects collectively generated hundreds of millions in global earnings, positioning Chase as a top comedy draw with aggregate box-office contributions exceeding $643 million across his leading roles, though reliance on physical gags and formulaic plots drew scrutiny for limiting dramatic range.[56]Career Challenges and Declines

1990s Professional Stumbles and Typecasting

Chase's transition into the 1990s marked a departure from the commercial peaks of his 1980s film career, with several projects failing to replicate prior successes. Nothing But Trouble (1991), a dark comedy directed by and co-starring Dan Aykroyd, earned just $8.5 million at the domestic box office against an estimated $40 million budget, marking a significant financial disappointment.[57] [58] Similarly, Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992), where Chase played a man rendered invisible after an accident, grossed $14.4 million domestically on a $40 million budget, underperforming relative to expectations for a major release.[59] [60] These films highlighted a pattern of box office shortfalls that contrasted with the high earnings of earlier hits like National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (1989). In television, Chase attempted a late-night talk show format with The Chevy Chase Show, which premiered on Fox on September 7, 1993, but was axed after only 28 episodes amid plummeting ratings and production issues.[61] [62] Despite heavy promotion as a hip alternative to established programs, the show's debut drew a 5.4 rating but quickly lost viewers, leading to its cancellation in mid-October 1993 and reinforcing perceptions of Chase's difficulty adapting to new formats.[63] Subsequent films like Cops and Robbersons (1994), a family comedy involving a stakeout next door to Chase's character, grossed $11.4 million, continuing the trend of modest returns insufficient to sustain leading-man status.[64] [65] Typecasting emerged as a key challenge, with Chase frequently slotted into roles as a sarcastic, physically comedic everyman—echoing his Clark Griswold persona from the Vacation series—rather than branching into dramatic or varied characters. Observers attributed this to his limited acting range beyond deadpan humor and slapstick, which became less viable as he aged out of the youthful wise-guy archetype that defined his breakthrough.[66] This reliance on formulaic comedy roles, combined with the era's shifting preferences toward edgier or ensemble-driven humor, constrained opportunities and amplified the impact of commercial stumbles.[67]Television Attempts and Set Conflicts (2000s–2010s)

Chevy Chase returned to a starring role on television with the NBC sitcom Community, which premiered on September 17, 2009, playing the curmudgeonly millionaire Pierce Hawthorne across 83 episodes through 2014.[41] His character, a recurring antagonist among the study group at Greendale Community College, drew on Chase's established comedic persona of bumbling authority figures, though the role required ensemble dynamics that clashed with his preferences for lead status.[68] Set conflicts emerged early, with Chase voicing dissatisfaction over scripts and the show's direction, leading to leaked voicemails in which he criticized creator Dan Harmon's writing as inadequate and suggested the series should end.[69] Harmon responded by incorporating elements of Chase's complaints and behavior into Pierce's dialogue, such as lines mocking the actor's age and irrelevance, which heightened tensions.[69] Chase walked off set multiple times during season 3 production in 2012, citing creative differences and physical discomfort from filming demands.[9] Incidents escalated when, in November 2012, Chase used a racial slur referring to co-star Donald Glover during a phone call overheard on set, prompting NBC to issue a warning and Glover to publicly address the hostility.[6] [9] Further disputes included physical altercations, such as Joel McHale dislocating Chase's shoulder during a rehearsal scuffle, amid broader complaints from cast members about Chase's negativity and absenteeism.[70] Chase's contract was not renewed after season 3, and he exited midway through season 4 filming in June 2013 following a heated argument with Harmon, who had returned as showrunner; Pierce was killed off-screen in season 5.[68] [9] In subsequent interviews, Chase described Community as "not funny enough" and stated he felt happier without the cast, attributing his departure to mutual incompatibility rather than solely his conduct.[71] No other sustained television series roles followed in the 2010s, marking Community as his primary small-screen effort of the era.[72]

Later Projects and Retirement from Regular Roles (2015–present)

Following his departure from the television series Community during its fourth season in 2012, Chevy Chase has not taken on any recurring roles in scripted television programming.[73] His output has shifted to infrequent film appearances and television movies, often in supporting or voice capacities, reflecting a marked reduction in activity consistent with semi-retirement at age 71 onward.[72] In 2015, Chase appeared in two films: a brief role as the Repairman in Hot Tub Time Machine 2, a sequel to the 2010 time-travel comedy, and a cameo reprise of his iconic character Clark Griswold from the National Lampoon's Vacation franchise in the reboot Vacation, directed by John Francis Daley and Jonathan Goldstein.[41] These marked his last major theatrical releases tied to prior career highlights, though both received mixed critical reception for relying on nostalgia over fresh material. Subsequent projects dwindled further. In 2017, he portrayed Sonny, a former child actor, in The Last Movie Star, a meta-comedy starring Burt Reynolds that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival before a limited release, earning modest praise for its leads' chemistry but criticism for uneven pacing. That year, he also voiced the character Thinkman in the animated family film Hedgehogs and starred as Preston in the Hallmark-style TV movie A Christmas in Vermont.[41] From 2018 to 2022, Chase's on-screen work was minimal, limited to uncredited or minor contributions amid personal health challenges, including a near-fatal heart failure in early 2021 at age 77.[74] He resumed sporadically in 2023 with a role as Mezmerian in R.L. Stine's Zombie Town, a family horror-comedy adaptation released directly to streaming, and voiced Santa Claus in the Netflix animated special Glisten and the Merry Mission.[75] In 2024, he appeared in the low-budget holiday films The Christmas Letter and Twinkly Christmas, both emphasizing sentimental family themes over his earlier physical comedy style, as Chase has noted avoiding strenuous roles due to age-related limitations.[5][75][76] Chase has not publicly declared full retirement, but in a 2022 interview, he described enjoying improvisation and a low-key lifestyle post-health scare, while a 2025 appearance at the Saturday Night Live 50th anniversary event focused on reflecting on his early career rather than new commitments.[74][77] Industry observers attribute the scarcity of offers to his history of on-set tensions, though he maintains selective involvement in voice and holiday projects suitable for his current physical condition.[78]Personal Life

Marriages and Family Dynamics

Chevy Chase's first marriage was to Susan Hewitt in 1973, ending in divorce in 1976 with no children from the union.[79] His second marriage to Jacqueline Carlin occurred on December 4, 1976, and concluded via divorce on November 14, 1980, also without issue.[2] Chase's third and current marriage is to Jayni Luke, wed on June 19, 1982; the couple has remained together for over four decades, crediting mutual support amid personal challenges.[2][80] Chase and Jayni have three daughters: Cydney Cathalene, born January 4, 1983; Caley Leigh, born January 19, 1985; and Emily Evelyn, born in 1988.[81] The family has maintained a low public profile, with the daughters occasionally appearing alongside Chase at events or in media, such as Cydney's involvement in his professional circles.[81] Jayni has been instrumental in family stability, particularly in supporting Chase through substance abuse recovery, which he has publicly attributed to her influence in pulling him from professional and personal "doldrums."[82] This partnership contrasts with Chase's earlier marital brevity and his reported interpersonal tensions elsewhere, fostering a resilient home environment despite external career volatility.[83]Substance Abuse and Health Struggles

Chase developed chronic back pain from the physical demands of slapstick comedy during his time on Saturday Night Live and subsequent films, which included frequent falls and stunts.[84] This condition led to dependency on prescription painkillers, culminating in his admission to the Betty Ford Center in October 1986 for treatment of addiction to these medications.[84][85] Earlier in his career, Chase acknowledged recreational drug use, including an incident during the first season of Saturday Night Live in 1975 where castmate John Belushi took his cocaine.[85] Despite claiming in a 2010 Esquire interview that he was not heavily involved in recreational drugs, his painkiller issues stemmed directly from managing long-term back injuries.[86] In September 2016, Chase entered the Hazelden Betty Ford treatment center in Minnesota for an alcohol-related "tune-up," as described by his publicist, amid ongoing struggles with the substance.[86][87] This followed a history of alcohol use that reportedly contributed to personal and professional challenges, though Chase has not publicly detailed further relapses post-2016. Beyond substance issues, Chase experienced a near-fatal heart failure in 2021, from which he reported subsequent memory loss during recovery.[88] In late 2023, he suffered a fall that resulted in a bruised knee requiring medical attention.[89] He has also spoken of battles with depression, exacerbated by career downturns and physical ailments, though without confirmed diagnoses in public records.[90] These health events have intersected with his substance history, as pain management and stress contributed to addictive patterns.[91]Political Views and Public Stances

Chevy Chase has consistently identified as a liberal Democrat throughout his career. During the 1970s, while performing on Saturday Night Live, he described himself as a "very liberal Democrat" motivated by a desire to parody political figures and prevent Richard Nixon's re-election, aligning his comedy with anti-Nixon sentiments prevalent in liberal circles at the time.[92][93] Despite satirizing Republican President Gerald Ford through exaggerated clumsiness on the show, Chase recounted that Ford personally told him the impressions "helped a lot" with his public image, indicating a professional rapport despite ideological differences.[94] In later years, Chase maintained his Democratic leanings without significant shifts, publicly criticizing Republican figures. He labeled Donald Trump "stupid" in a 2018 interview, reflecting disdain for Trump's persona and policies.[95] Chase also accused Trump of appropriating his signature SNL catchphrase in 2017, noting Trump's use of "I'm the president, and you're not" as echoing "I'm Chevy Chase, and you're not."[96] While occasionally agreeing with Trump on specific cultural critiques, such as calling Alec Baldwin's SNL Trump impersonation "rough," Chase reaffirmed his unchanged liberal Democratic views.[94] Beyond partisanship, Chase has advocated for environmental causes, emphasizing global warming and energy conservation as key issues in tracking political candidates during the 2007 presidential campaign.[97] He has also supported animal rights organizations, including PETA and the Humane Society of the United States, aligning with progressive priorities on welfare and ethics. These stances underscore a worldview rooted in liberal interventionism on social and environmental matters, though Chase has rarely engaged deeply in formal political activism or endorsements beyond public commentary.[93]Controversies

On-Set Feuds and Professional Relationships

Chase's tenure on Saturday Night Live from 1975 to 1976 was marred by interpersonal conflicts that foreshadowed his later professional difficulties. He departed after the first season amid reported ego clashes with castmates and producer Lorne Michaels, believing his stardom warranted a pivot to film.[98] A notable feud erupted with incoming cast member Bill Murray; on February 18, 1977, just before Murray's debut, Chase punched him backstage following Murray's alleged mockery of Chase's exit and physical condition.[99] [100] The two rivals reconciled publicly around 2023 after decades of animosity rooted in competitive tensions post-Chase's departure.[101] Chase also clashed with John Belushi, their rivalry originating at The Second City improv troupe and escalating on SNL over creative dominance and personal slights.[102] On the NBC sitcom Community (2009–2015), Chase's role as Pierce Hawthorne ended acrimoniously after repeated disruptions and offensive behavior. Starting in season 1, he voiced complaints via leaked voicemails in November 2012, criticizing scripts as insufficiently funny and making racially charged references to co-stars Donald Glover and Yvette Nicole Brown.[9] Glover later recounted Chase disrupting his scenes, muttering racial jokes between takes, and questioning his talent with remarks like "People think you're funny because you're black."[103] In June 2012, during a dispute with showrunner Dan Harmon, Chase uttered the N-word, prompting an apology but escalating tensions.[104] These incidents culminated in Chase's removal from the series in November 2012 during production of season 4, with his character written out via death in season 5; he was formally fired in 2013 following a physical altercation with Harmon.[8][9] Beyond television, Chase's on-set conduct strained other productions. During filming of National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (1989), his unprofessional antics—including tardiness and improvisational demands—drove initial director Chris Columbus to resign after two weeks, with Jeremiah S. Chechik replacing him.[105] Accounts from multiple collaborators describe a pattern of verbal abusiveness, scene sabotage, and entitlement, contributing to his exclusion from subsequent industry opportunities.[106][107] Despite these issues, some peers, like Murray post-reconciliation, acknowledged Chase's comedic talent while critiquing his interpersonal style.[101]Offensive Remarks and Behavioral Incidents

Throughout his career, Chevy Chase has been involved in several incidents involving offensive remarks, particularly racial slurs and derogatory comments toward colleagues. On the set of the NBC sitcom Community (2009–2014), Chase repeatedly directed racial jokes at co-star Donald Glover between takes, with show creator Dan Harmon stating that Chase used these remarks strategically "to disrupt" Glover's performance. Glover recounted Chase telling him, "People think you're funny because you're Black," a comment Glover interpreted as undermining his talent based on race. These interactions contributed to tensions, as corroborated by multiple cast and crew accounts. In October 2012, during a heated outburst on the Community set, Chase used the N-word multiple times while criticizing his character's dialogue and the show's writing, reportedly yelling phrases including "How do you expect me to say this shit?" followed by the slur in frustration over perceived overly racial content. Co-star Joel McHale later confirmed Chase's use of the racial epithet during this tirade, which upset the cast and led to production pauses. Chase apologized shortly after, with reports noting the remarks appeared inconsistent with his history of participating in civil rights marches in the 1960s.[108][109] Broader accusations of homophobic and misogynistic behavior have surfaced from co-workers across projects, though specific remarks are less documented publicly. For instance, accounts describe Chase employing derogatory language toward women and LGBTQ+ individuals in off-camera interactions, aligning with patterns of verbal aggression reported by former colleagues like those on Saturday Night Live and later shows. Comedian Pete Davidson publicly labeled Chase a "genuinely bad, racist person" in 2018, citing personal encounters and Chase's critical comments about SNL's modern cast. Chase has acknowledged being a "jerk" in interviews but attributed much of his conduct to personal struggles and age, denying systemic racism while maintaining the Community conflicts stemmed from script quality rather than prejudice.[110][111][8]Consequences and Industry Reception

Chase's use of a racial slur on the set of Community in November 2012, during a dispute over his character's increasingly bigoted dialogue, prompted a temporary halt in production and escalated tensions with showrunner Dan Harmon.[112] This incident, combined with prior conflicts including Chase leaving hostile voicemails for Harmon criticizing the show's scripts, culminated in his dismissal from the series in November 2013 after filming 83 episodes across four seasons.[113] His character, Pierce Hawthorne, was subsequently written out via an off-screen death in season 5, limiting any further narrative involvement.[114] The firing marked a significant professional setback, effectively ending Chase's attempt at a television resurgence and reinforcing perceptions of him as unreliable on set.[115] Post-Community, Chase's opportunities dwindled to sporadic voice work, such as in Hot Tub Time Machine 2 (2015) and The Christmas Chronicles (2018), with no major leading roles or series commitments.[106] Industry figures, including Community cast member Joel McHale, have cited Chase's behavior as barring him from projects like the planned Community film, stating in April 2024 that Chase "isn't allowed" to participate due to past conduct.[116] Reception within Hollywood has been predominantly negative, with co-stars and colleagues describing Chase's pattern of offensive remarks—ranging from racial slurs to misogynistic comments—as creating a toxic environment across multiple productions.[7] Donald Glover, who faced targeted racial jokes from Chase on Community, highlighted this in a 2018 New Yorker interview, contributing to a broader narrative of Chase as "horrific" and professionally isolating.[7] Comedian Pete Davidson echoed this in 2018, publicly labeling Chase a "genuinely bad, racist person" amid defenses of Saturday Night Live leadership.[117] Such accounts, corroborated across outlets, have solidified a reputation that has deterred collaborations, though Chase has dismissed criticisms as exaggerated or motivated by personal grudges.[118]Legacy and Professional Output

Filmography Highlights

Chevy Chase transitioned from television to film in the late 1970s, establishing himself as a leading man in comedic roles. His debut starring role came in Foul Play (1978), a romantic thriller directed by Colin Higgins, where he played undercover agent Tony Carlson opposite Goldie Hawn's Gloria Mundy; the film grossed $40.4 million domestically on a $5 million budget, marking a commercial success.[43] This was followed by Caddyshack (1980), in which Chase portrayed the laid-back Ty Webb, a pivotal character in the ensemble comedy about class tensions at a country club; despite mixed critical reception, it earned $39.8 million domestically and achieved cult status for its quotable lines and improvisational style.[119] The National Lampoon's Vacation series solidified Chase's screen persona as the hapless everyman Clark W. Griswold, beginning with the 1983 original directed by Harold Ramis, which depicted a disastrous family road trip and grossed $61.4 million domestically.[120] The franchise's pinnacle came with National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (1989), focusing on holiday mishaps, that outperformed predecessors by earning $74.5 million domestically and becoming a perennial favorite for its portrayal of suburban frustrations.[121] Chase reprised the role in sequels like National Lampoon's European Vacation (1985, $49.4 million domestic) and Vegas Vacation (1997), though later entries received diminishing critical praise while maintaining audience appeal through Chase's physical comedy.[122] Other 1980s highlights include Fletch (1985), where Chase embodied investigative reporter Irwin M. Fletcher in an adaptation of Gregory Mcdonald's novel, delivering a box office hit with $50.6 million domestic earnings praised for his deadpan delivery amid disguises and satire of journalism.[53] Films like Three Amigos! (1986) and Spies Like Us (1985) showcased Chase in buddy comedies, the former as Dusty Bottoms in a Western spoof grossing $39.2 million worldwide and the latter pairing him with Dan Aykroyd for Cold War parody, though neither matched the financial peaks of his Griswold or Fletcher vehicles. Later career films, such as Funny Farm (1988), saw Chase in lead roles but with declining box office returns, reflecting a shift toward supporting parts in the 1990s and beyond.[123]Television Contributions