Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

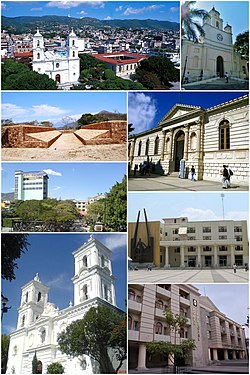

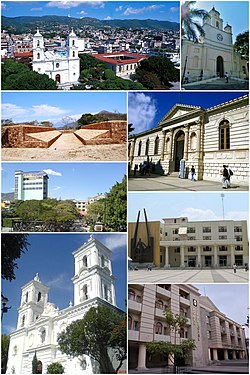

Chilpancingo

View on WikipediaChilpancingo de los Bravo (commonly shortened to Chilpancingo; Spanish pronunciation: [tʃilpanˈsiŋɡo] ⓘ; Nahuatl: Chilpantzinco (pronounced [t͡ʃiɬpanˈt͡siŋko])) is the capital and second-largest city of the Mexican state of Guerrero. In 2010 it had a population of 187,251 people. The municipality has an area of 2,338.4 km2 (902.9 sq mi) in the south-central part of the state, situated in the Sierra Madre del Sur mountains, on the bank of the Huacapa River.[1] The city is on Federal Highway 95, which connects Acapulco to Mexico City. It is served by Chilpancingo National Airport, which is one of the five airports in the state.

Key Information

History

[edit]In pre-Columbian times, the area was occupied by the Olmecs, who built an extensive tunnel network through the mountains, and left the cave paintings in the caverns of Juxtlahuaca.[1] The city of Chilpancingo was founded on 1 November 1591 by the Spanish conquistadores, its name meaning "Place of Wasps" in Nahuatl.[1] During the War of Independence, Chilpancingo was crucial to the insurgent cause as its population participated actively and decisively in their favor, and it became a strategic point for military action in the south. Chilpancingo was very important to Mexican history because it was here where the National Congress met under José María Morelos y Pavón in 1813 during the War of Independence.[2]

General Nicolás Catalán, husband of the independence war heroine Antonia Nava de Catalán, was made commander of the state of Guerrero on 24 January 1828. The family settled in Chilpancingo, where both Nicolás and Antonia later died.[3] In 1853, Chilpancingo was declared the provisional capital of the state, due to an epidemic that struck the then capital of Tixtla, and regional ecclesiastical organizational changes were made at the same time.[4] In 1870 it was again declared capital by Governor Francisco O. Arce, due to the opposition led by General Jiménez, who was in possession of the official seat of government at Tixtla. It was not until 1871, when the state legislature agreed to a change of venue, that the capital was moved again from Chilpancingo.[5]

During the Mexican Revolution, Chilpancingo was deeply troubled and had political and administrative importance as a strategic place for the sides in the debate. Battles took place in the vicinity in the 1910s, in which Emiliano Zapata defeated federal forces of Porfirio Díaz, Francisco I. Madero, Victoriano Huerta and Venustiano Carranza. A major defeat of Huerta's southern forces took place here in March-April 1914;[6] the Zapatistas took the town until after the 1917 Constitutional Convention.

In 1960, the city entered a severe social crisis with the start of a student popular movement at the Autonomous University of Guerrero, protests which led to a general strike at the institution and later swarmed to various forces and social sectors of the city and the state.[7] The main objective was to diminish the power of the state government and seek autonomy for the college. On 27 April 2009 an earthquake with a magnitude of 5.6 was centered near Chilpancingo.[8]

On 6 October 2024, mayor Alejandro Arcos was beheaded just six days after taking office, allegedly by drug cartels. His murder came three days after Francisco Tapia, the city government's secretary, was shot to death.[9][10]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]The climate of Chilpacingo is classified as a tropical savanna climate ("Aw"). There is some moderation due to high elevation, but high temperatures are still in the upper 20s °C (80s °F) for most of the year.

| Climate data for Chilpancingo de los Bravo (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.0 (95.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

35.5 (95.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.8 (0.70) |

3.1 (0.12) |

2.8 (0.11) |

17.2 (0.68) |

63.1 (2.48) |

162.4 (6.39) |

191.1 (7.52) |

152.7 (6.01) |

165.8 (6.53) |

78.1 (3.07) |

16.9 (0.67) |

2.8 (0.11) |

873.8 (34.40) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 16.1 | 21.1 | 19.1 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 97.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 73 | 70 | 69 | 73 | 82 | 84 | 84 | 87 | 82 | 78 | 76 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 213.9 | 211.9 | 232.5 | 195.0 | 176.7 | 147.0 | 164.3 | 170.5 | 135.0 | 179.8 | 198.0 | 201.5 | 2,226.1 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[11][12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun and humidity 1941–1970)[13] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]In 1869, the Autonomous University of Guerrero was established in Chilpancingo; it still plays a considerable role in the local economy. The city is a producer of processed foods and alcoholic beverages, and is a market for maize, sugarcane, bananas, livestock, and lumber produced in the region.[1]

Archaeology

[edit]Pezuapan is an archaeological site located in the city of Chilpancingo.[14] It sits on the eastern slope of the Chilpancingo valley. The archaeological vestiges found at the site cover the total area of 4000 m². The dates are from 650 AD to 1150 AD.

Other archaeological sites found in this area of Guerrero are:

Government

[edit]Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] McAllen, United States

McAllen, United States Cavite City, Philippines

Cavite City, Philippines

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Chilpancingo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Mills, Kenneth R.; Taylor, William B.; Graham, Sandra Lauderdale (1 January 2002). Colonial Latin America: A Documentary History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-8420-2997-1.

- ^ Acuña Cepeda, Mirtea Elizabeth (19 November 2017), "Antonia Nava de Catalán, la Generala", Ecos de la Costa (in Spanish), archived from the original on 1 December 2017, retrieved 2017-11-28

- ^ Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 1966. p. 7. ISBN 9781422374764. ISSN 0065-9746.

- ^ "Chilpancingo de los Bravo" (in Spanish). Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ O'Kane, Rosemary H. T. (2000). Revolution: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Taylor & Francis. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-415-20135-3.

- ^ Selee, Andrew D. (2011). Decentralization, Democratization, and Informal Power in Mexico. Penn State Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-271-04843-7.

- ^ "Mexico Earthquake: Felt In Mexico City, Centered Near Chilpancingo". Huffington Post. 28 May 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Mexican mayor murdered days after starting job". www.bbc.com. 7 October 2024. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Kelly, Kieran (7 October 2024). "Mexican mayor 'decapitated by drug gangs' six days into job". Yahoo News. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ "Estado de Guerrero–Estacion: Chilpancingo (DGE)". NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1951–2010 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures and Precipitation for Chilpancingo (DGE) 1953-1991" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Chilpancingo Los Bravos, Guerrero / Mexiko" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Reyna Beatríz SOLÍS CIRIACO, Hervé Victor MONTERROSA DESRUELLES, Malacological Material from Pezuapan's Archaeological site, Chilpancingo, Guerrero, Mexico. 2010

External links

[edit]- Ayuntamiento de Chilpancingo de los Bravo Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Official website