Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

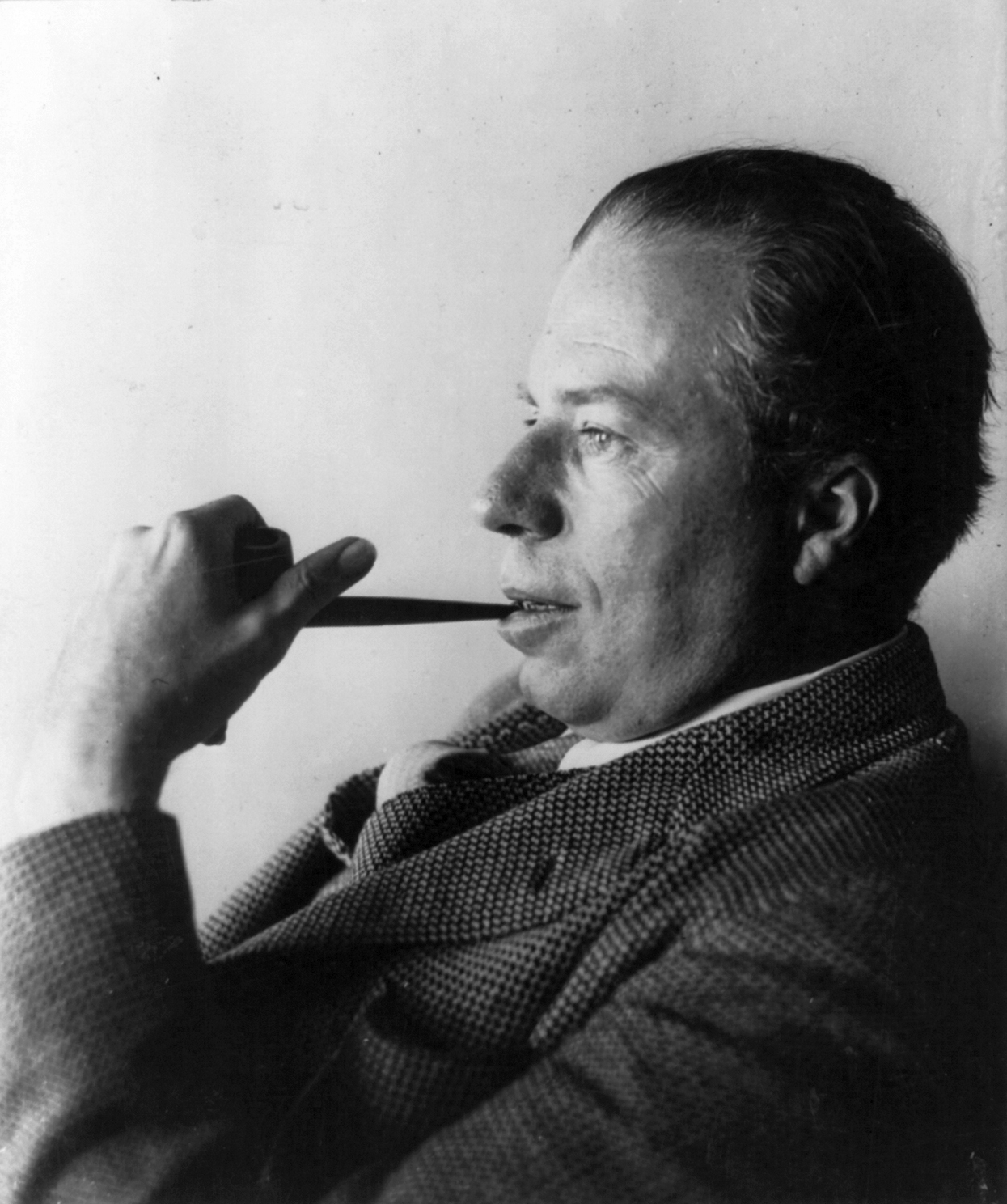

Christopher Morley

View on Wikipedia

Christopher Darlington Morley (May 5, 1890 – March 28, 1957) was an American journalist, novelist, essayist and poet. He also produced stage productions for a few years and gave college lectures.[1]

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Morley was born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. His father, Frank Morley, was a mathematics professor at Haverford College; his mother, Lilian Janet Bird, was a violinist who provided Christopher with much of his later love for literature and poetry.[1]

In 1900, the family moved to Baltimore, Maryland. In 1906 Christopher entered Haverford College, graduating in 1910 as valedictorian. He then went to New College, Oxford, for three years on a Rhodes scholarship, studying modern history.[2]

In 1913 Morley completed his Oxford studies and moved to New York City, New York. On June 14, 1914, he married Helen Booth Fairchild, with whom he would have four children, including Louise Morley Cochrane. They first lived in Hempstead, and then in Queens Village. They then moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and in 1920 they made their final move to a house they called "Green Escape" in Roslyn Estates, New York. They remained there for the rest of his life. In 1936 he built a cabin at the rear of the property (The Knothole), which he maintained as his writing study from then on.[1]

In 1951, Morley had a series of strokes, which greatly reduced his voluminous literary output. He died on March 28, 1957, and was buried in the Roslyn Cemetery in Nassau County, New York. After his death, The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune published his message to his friends and readers:[1]

Read, every day, something no one else is reading. Think, every day, something no one else is thinking. Do, every day, something no one else would be silly enough to do. It is bad for the mind to be always part of a unanimity.

This quote originally appeared in Morley's column "Brief Case; or, Every Man His Own Bartlett" in The Saturday Review of Literature, November 6, 1948.[3]

Career

[edit]Morley began writing while still in college. He edited The Haverfordian and contributed articles to that college publication. He provided scripts for and acted in the college's drama program. He played on the cricket and soccer teams.

In Oxford a volume of Morley's poems, The Eighth Sin (1912), was published.[4] After graduating from Oxford, Morley began his literary career at Doubleday, working as publicist and publisher's reader. In 1917, he got his start as an editor for Ladies' Home Journal (1917–1918), then as a newspaper reporter and newspaper columnist in Philadelphia for the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger.

Morley's first novel, Parnassus on Wheels, appeared in 1917. The protagonist, traveling bookseller Roger Mifflin, appeared again in his second novel, The Haunted Bookshop in 1919.

In 1920, Morley returned to New York City to write a column (The Bowling Green) for the New York Evening Post.[5]

In 1922, a candid interview was seen nationwide in newspapers, part of a series called Humor's Sober Side: How Humorists Get That Way. Other humorists interviewed in the same series included Will Rogers, Dorothy Parker, Don Marquis, Roy K. Moulton, Tom Sims, Tom Daly, and Ring Lardner.[6]

Morley was one of the founders and a longtime contributing editor of the Saturday Review of Literature. A highly gregarious man, he was the mainstay of what he dubbed the "Three Hours for Lunch Club". Out of enthusiasm for the Sherlock Holmes stories, he helped found the Baker Street Irregulars[1] and wrote the introduction to the standard omnibus edition of The Complete Sherlock Holmes.

"Kit" wrote prefaces, introductions, or forewords for over fifty books. Many of these were posthumously collected as Prefaces without Books.[7] A lion of literature, Morley was able in these essays to analyze subtleties within the Sherlock Holmes stories, for example, examining the influences of Doyle's youthful love of Robert Louis Stevenson's writings upon the Holmes stories. But Morley goes much further, analyzing the Holmes stories as if they are historical artifacts. For examples, he peruses maps of the British sea coast to try to determine the location of Holmes' retirement bee-keeping, he tries to develop a floor plan for Holmes' Baker Street residence, and he conjectures about Watson's love life.

Morley explained, "Is it trivial or absurd to apply to these imaginary characters the same close attention which is the principle of the stories themselves?" and "There is a special and superior pleasure in reading anything so much more carefully than its author ever did."[8]

He also wrote an introduction to the standard omnibus edition of The Complete Works of Shakespeare in 1936, although Morley called it an "Introduction to Yourself as a Reader of Shakespeare".[9] That year, he was appointed to revise and enlarge Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (11th edition in 1937 and 12th edition in 1948). He was one of the first judges for the Book of the Month Club, serving in that position until the early 1950s.

Author of more than 100 novels, books of essays, and volumes of poetry, Morley is probably best known today for his first two novels, Parnassus on Wheels (1917) and The Haunted Bookshop (1919), which remain in print. Barnes & Noble published new editions of these works in 2009 as part of their "Library of Essential Reading" series.[10][11] In 2018, Dover Publications published a new single volume edition containing both novels.[12] Other well-known works include Thunder on the Left (1925) and the 1939 novel Kitty Foyle, which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie.

From 1928 to 1930, Morley and set designer Cleon Throckmorton co-produced theater productions (dramas) at two theaters they purchased and renovated in Hoboken, New Jersey,[1][13] which they had "deemed the last seacoast in Bohemia".[14][15][16]

For most of Morley's life, he lived in Roslyn Estates, Nassau County, Long Island, commuting to the city on the Long Island Rail Road, about which he wrote affectionately. In 1961, the 98-acre (40-hectare) Christopher Morley Park[17] on Searingtown Road in Nassau County was named in his honor. This park preserves as a publicly available point of interest his studio, the "Knothole" (which was moved to the site after his death), along with his furniture and bookcases.

Notable works

[edit]

- Parnassus on Wheels (novel, 1917)

- Shandygaff (travel and literary essays, short stories 1918)

- The Haunted Bookshop (novel, 1919)

- The Rocking Horse (poetry, 1919)

- Pipefuls (collection of humorous essays, 1920)

- Kathleen (novel, 1920)

- Travels in Philadelphia (collection of essays, 1920, illustrated by Herbert Pullinger, and Frank H Taylor)

- Plum Pudding, of divers Ingredients, Discreetly Blended & Seasoned (collection of humorous essays, 1921, illustrated by Walter Jack Duncan)

- Where the Blue Begins (satirical novel, 1922)

- The Powder of Sympathy (collection of humorous essays, 1923, illustrated by Walter Jack Duncan)

- Religio Journalistici (1924)

- Thunder on the Left (novel, 1925)

- The Romany Stain (Short stories, 1926)

- I know a Secret (Novel for children, 1927)

- Essays by Christopher Morley (collection of essays, 1928)

- Off the Deep End (collection of essays, 1928, illustrated by John Alan Maxwell)

- Seacoast of Bohemia ("history of four infatuated adventurers, Morley, Cleon Throckmorton, Conrad Milliken and Harry Wagstaff Gribble, who rediscovered the Old Rialto Theatre in Hoboken, and refurnished it", 1929, illustrated by John Alan Maxwell)

- Born in a Beer Garden, or She Troupes to Conquer (with Cleon Throckmorton and Ogden Nash, 1930)

- John Mistletoe (autobiographical novel, 1931)

- Swiss Family Manhattan (novel, 1932)

- Ex Libris Carissimis (non-fiction writing based on lectures he presented at University of Pennsylvania, 1932)

- Shakespeare and Hawaii (non-fiction writing based on lectures he presented at University of Hawaiʻi, 1933)

- Human Being (novel, Doubleday, Doran & Co., Garden City, New York, 1934)[18]

- Ex Libris (1936)

- The Trojan Horse (novel, 1937) Rewritten as a play and produced 1940[19]

- Kitty Foyle (novel, 1939)

- Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson: A Textbook of Friendship (analysis of Arthur Conan Doyle's writings, 1944)

- The Old Mandarin (book of poetry, 1947)

- The Man Who Made Friends with Himself (his last novel, 1949)[1]

- On Vimy Ridge (poetry, 1947)

- The Ironing Board (essays, 1949)

Literary connections

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2025) |

- Morley was a close friend of Don Marquis, author of the Archy and Mehitabel stories featuring the antics and commentary of a New York cockroach and a cat. In 1924 Morley and Marquis co-authored Pandora Lifts The Lid, a light novel about the well-to-do in the contemporary Hamptons. They are said to have written alternating chapters, each taking the plot forward from where the other had left off.

- Morley's widow sold a collection of his personal papers and books to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin after his death.

- Morley helped to found The Baker Street Irregulars, dedicated to the study of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes.

- Morley edited two editions of Bartlett's Familiar Quotations: 1937 (11th) and 1948 (12th).

- Morley's 1939 novel Kitty Foyle was unusual for its time, as it openly discussed abortion. It became an instant best-seller, selling over one million copies.

- Morley's brothers Felix and Frank were also Rhodes Scholars. Felix became President of Haverford College.[1]

- In 1942, Morley wrote his own obituary for the biographical dictionary Twentieth Century Authors.

- Morley was at the center of a social group in Greenwich Village that hung out at his friend Frank Shay's bookshop at 4 Christopher Street in the early 1920s.

- Morley's selected poems are available as Bright Cages: Selected Poems And Translations From The Chinese by Christopher Morley, ed. Jon Bracker (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1965). The translations from the Chinese are actually a joke, explained to the public when the volumes by Morley containing them appeared: they are "Chinese" in nature, good-humored accounts: short, wise, often humorous. But they are not in any strict sense of the word, translations.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Online Literature page for Christopher Morley. Accessed March 27, 2023.

- ^ Baltimore Literary Heritage Project

- ^ The Saturday Review of Literature, Volume 31, Number 45 (November 6, 1948), page 20. Retrieved from Internet Archive March 27, 2023.

- ^ Lieberman, Gerald F. (May 20, 1973). "Morley Collection presented to Roslyn". The New York Times.

- ^ Living the Literary Life - Mass Media, New York, The New York Times - Newsday.com

- ^ van der Grift, Josephine. (October 19, 1922). "Humor's sober side: Being an interview with Christopher Morley, another of a series on how humorists get that way", Bisbee Daily Review, p. 4.

- ^ "Prefaces without Books," copyright 1970 by the Humanities Research Center, as noted in "The Standard Doyle Company: Christopher Morley on Sherlock Holmes," edited by Steven Rothman, copyright 1990 by the Estate of Christopher Morley, page 88.

- ^ "Memorandum and Introduction to "Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson: A Textbook of Friendship," Christopher Morley editor, copyright 1944 by Harcourt Brace, and later published in "The Standard Doyle Company: Christopher Morley on Sherlock Holmes," edited by Steven Rothman, copyright 1990 by the Estate of Christopher Morley, pages 115, 116.

- ^ Wallach, Mark I., Bracker, Jon. "Christopher Morley". Twayne Publishers, 1976. 112.

- ^ Noble, Barnes &. "The Haunted Bookshop|NOOK Book". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ Noble, Barnes &. "Parnassus on Wheels (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)|NOOK Book". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "Christopher Morley: Two Classic Novels in One Volume: Parnassus on Wheels and The Haunted Bookshop". store.doverpublications.com. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "The New Yorker Digital Edition : April 20, 1929". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ Yarrow, Andrew L. (November 15, 1985). "Hoboken, A 10-Minute Ride to Far Away". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Theatre: In Hoboken". Time. March 25, 1929.

- ^ "Theatre: New Play in Hoboken". Time. October 7, 1929.

- ^ "Christopher Morley Park | Nassau County, NY - Official Website".

- ^ cover page of the novel

- ^ "'The Trojan Horse'", Life, November 25, 1940, page 56

External links

[edit]- Works by Christopher Morley in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Christopher Morley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Christopher Morley at Faded Page (Canada)

- Christopher Morley Collection at the Harry Ransom Center

- Works by or about Christopher Morley at the Internet Archive

- Works by Christopher Morley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Christopher Morley index entry at Poets' Corner

- Essays by Morley at Quotidiana.org

- The Baker Street Journal Writings about Sherlock Holmes

- The Baker Street Irregulars Weekend

- — Biography

- Christopher Morley Quotes

Christopher Morley

View on GrokipediaChristopher Darlington Morley (May 5, 1890 – March 28, 1957) was an American novelist, journalist, poet, essayist, and playwright whose versatile and humorous writings spanned over 100 books, articles, and essays.[1][2] Born in Haverford, Pennsylvania, to a family of educators, Morley graduated from Haverford College in 1910 and briefly studied at Oxford before embarking on a multifaceted literary career that included editing magazines and producing theater.[3][4] His most enduring works include the novels Parnassus on Wheels (1917) and its sequel The Haunted Bookshop (1919), which celebrate the joys of bookselling and reading, and Kitty Foyle (1939), a social novel adapted into a successful film starring Ginger Rogers.[2][3][1] Morley also founded the Baker Street Irregulars in 1934, the world's first major Sherlock Holmes society, fostering scholarly and enthusiast engagement with Arthur Conan Doyle's detective.[1]