Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mono (software)

View on Wikipedia| Mono | |

|---|---|

| |

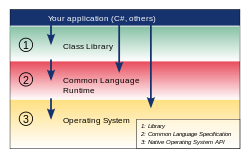

Diagram of Mono architecture | |

| Original author | Ximian |

| Developer | WineHQ |

| Initial release | June 30, 2004 |

| Stable release | 6.12.0.206

/ February 13, 2024[1] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C, C#, XML |

| Operating system | Windows, macOS, Linux, IBM AIX, IBM i[2] |

| Platform | IA-32, x64, IA-64, ARM, MIPS, RISC-V, PowerPC, SPARC, S390 |

| Type | Software framework |

| License | MIT License[3] |

| Website | www |

Mono is a free and open-source software framework that aims to run software made for the .NET Framework on Linux and other OSes. Originally by Ximian which was acquired by Novell, it was later developed by Xamarin which was acquired by Microsoft.[4] In August 2024, Microsoft transferred ownership of Mono to WineHQ.[5]

History

[edit]

When Microsoft first announced their .NET Framework in June 2000 it was described as "a new platform based on Internet standards",[6] and in December of that year the underlying Common Language Infrastructure was published as an open standard, "ECMA-335",[7] opening up the potential for independent implementations.[8] Miguel de Icaza of Ximian believed that .NET had the potential to increase programmer productivity and began investigating whether a Linux version was feasible.[9] Recognizing that their small team could not expect to build and support a full product, they launched the Mono open-source project, on July 19, 2001, at the O'Reilly conference.

After three years of development, Mono 1.0 was released on June 30, 2004.[10] Mono evolved from its initial focus of a developer platform for Linux desktop applications to supporting a wide range of architectures and operating systems - including embedded systems.[11]

Novell acquired Ximian in 2003. After Novell was acquired by Attachmate in April 2011, Attachmate announced hundreds of layoffs for the Novell workforce,[12] putting in question the future of Mono.[13][14]

On May 16, 2011, Miguel de Icaza announced in his blog that Mono would continue to be supported by Xamarin, a company he founded after being laid off from Novell. The original Mono team had also moved to the new company. Xamarin planned to keep working on Mono and had planned to rewrite the proprietary .NET stacks for iOS and Android from scratch, because Novell still owned MonoTouch and Mono for Android at the time.[15] After this announcement, the future of the project was questioned, MonoTouch and Mono for Android being in direct competition with the existing commercial offerings now owned by Attachmate, and considering that the Xamarin team would have difficulties proving that they did not use technologies they formerly developed when they were employed by Novell for the same work.[16] However, in July 2011, Novell, now a subsidiary of Attachmate, and Xamarin, announced that it granted a perpetual license to Xamarin for Mono, MonoTouch and Mono for Android, which officially took stewardship of the project.[17][18]

On February 24, 2016, Microsoft announced it had signed a definitive agreement to acquire Xamarin.[19]

On August 27, 2024, Microsoft transferred ownership of Mono to WineHQ, the developer team of Wine, a Windows compatibility layer.[5]

Current status and roadmap

[edit]Mono's current version is 6.12.0 (as of June 2024[update]). This version provides the core API of the .NET Framework and support for Visual Basic.NET and C# 7.0. LINQ to Objects, XML, and SQL are part of the distribution. Windows Forms 2.0 is also supported, but not actively developed, and as such its support on Mono is incomplete.[20] Version 4.0 was the first version that incorporates Microsoft original source code that was released by Microsoft as part of the .NET Core project.

As of January 14, 2021, Mono has full support for all the features in .NET 4.7 except Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) (which the Mono team do not plan to support due to the amount of work it would need)[20] and Windows Workflow Foundation (WF), and with only limited support for Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) and the ASP.NET async stack. However, System.Web and WCF are candidates for 'almost immediate' porting from the .NET reference source back to Mono.[21] Some missing parts of the .NET Framework are under development in an experimental Mono subproject called Olive.[22]

The Mono project has also created a Visual Basic .NET compiler and a runtime designed for running VB.NET applications. It is currently being developed by Rolf Bjarne Kvinge.

Moonlight

[edit]An open-source implementation of Microsoft Silverlight, called Moonlight, has been included since Mono 1.9.[23] Moonlight 1.0, which supports the Silverlight 1.0 APIs, was released January 20, 2009. Moonlight 2.0 supports Silverlight 2.0 and some features of Silverlight 3.0.[24] A preview release of Moonlight 3.0 was announced in February 2010 and contains updates to Silverlight 3 support.[25]

The Moonlight project was abandoned on May 29, 2012.[26] According to Miguel, two factors sealed the fate of the project: Microsoft added "artificial restrictions" that "made it useless for desktop programming", and the technology had not gained enough traction on the Web. In addition, Silverlight itself was deprecated by Microsoft by 2012.

Mono components

[edit]Mono consists of three groups of components:

- Core components

- Mono/Linux/GNOME development stack

- Microsoft compatibility stack

The core components include the C# compiler, the virtual machine for the Common Language Infrastructure and the core class libraries. These components are based on the Ecma-334 and Ecma-335 standards,[27] allowing Mono to provide a standards compliant, free and open-source CLI virtual machine. Microsoft issued a statement that covers both standards under their Community Promise license.[28]

The Mono/Linux/GNOME development stack provide tools for application development while using the existing GNOME and free and open-source libraries. These include: Gtk# for graphical user interface (GUI) development, Mozilla libraries for working with the Gecko rendering engine, Unix integration libraries (Mono.Posix), database connectivity libraries, a security stack, and the XML schema language RelaxNG. Gtk# allows Mono applications to integrate into the Gnome desktop as native applications. The database libraries provide connectivity to the object-relational database db4o, Firebird, Microsoft SQL Server (MSSQL), MySQL, Open Database Connectivity (ODBC), Oracle, PostgreSQL, SQLite, and many others. The Mono project tracks developing database components at its website.[29]

The Microsoft compatibility stack provides a pathway for porting Windows .NET applications to Linux. This group of components include ADO.NET, ASP.NET, and Windows Forms (and libgdiplus), among others. As these components are not covered by Ecma standards, some of them remain subject to patent fears and concerns.

Framework architecture

[edit]The major components of Mono include:

- Code Execution Engine

- Class Libraries

- Base Class Library

- .NET Compatibility Class Libraries

- Mono specific class libraries:

- Cross platform class libraries for both Mono and .NET (Gtk#, Mono.Cecil, Mono.CSharp, Text.Templating)

- Unix-specific class libraries (POSIX, Filesystem in Userspace (FUSE), curses)

- Platform-specific class libraries (bindings for: Mac, iOS, Android, MeeGo)

- CLI Assemblies

- CLI Metadata

- Mono's Common Language Runtime

- Compatible with the ECMA Common Language Infrastructure/.NET Common Language Runtime

- Mono-specific enhancements:

- Mono.SIMD support

- Mono co-routines and continuations.

- Mono-specific enhancements

- Native interop services and COM interop

- Security - Transparent Code Framework

Code Execution Engine

[edit]The Mono runtime contains a code execution engine that translates ECMA CIL byte codes into native code and supports a number of processors: ARM, MIPS (in 32-bit mode only), SPARC, PowerPC, z/Architecture, IA-32, x86-64 and IA-64 for 64-bit modes.

The code generator is exposed in three modes:

- Just-in-time (JIT) compilation: The runtime will turn ECMA CIL byte codes into native code as the code runs.

- Ahead-of-Time (AOT) compilation: this code turns the ECMA CIL byte codes (typically found on a .exe or .dll file) and generates native code stored in an operating system, architecture and CPU specific file (for a foo.exe file, it would produce foo.exe.so on Linux). This mode of operation compiles most of the code that is typically done at runtime. There are some exceptions like trampolines and other administrative code that still require the JIT to function, so AOT images are not fully standalone.

- Full Static Compilation: this mode is only supported on a handful of platforms and takes the Ahead-of-Time compilation process one step further and generates all the trampolines, wrappers and proxies that are required into a static file that can be statically linked into a program and eliminates the need for a JIT at runtime. This is used on Apple's iOS, Sony's PlayStation 3 and Microsoft's Xbox 360 operating systems.[citation needed]

Starting with Mono 2.6, it is possible to configure Mono to use the LLVM as the code generation engine instead of Mono's own code generation engine. This is useful for high performance computing loads and other situations where the execution performance is more important than the startup performance.

Starting with the Mono 2.7 preview, it is no longer necessary to pick one engine over the other at configuration time. The code generation engine can be selected at startup by using the --llvm or --nollvm command line arguments, and it defaults to the fast-starting Mono code generation engine.

Starting with Mono 5.18, support for LLVM is a default configuration option. Previous versions required a special LLVM fork, but now mono can fall back to its own code generator when it encounters something not handled by LLVM.[30]

Garbage collector

[edit]As of Mono 2.8, the Mono runtime ships with two garbage collectors: a generational collector and the Boehm–Demers–Weiser Conservative Garbage Collector. The Boehm garbage collector could exhibit memory leaks on certain classes of applications, making it unsuitable for some long-running server applications.[31][32] Mono switched to Simple Generational GC (SGen-GC) as the default collector in version 3.1.1.

The SGen garbage collector has many advantages over a traditional conservative scanner. It uses generational garbage collection where new objects are allocated from a nursery, during the garbage collection cycle, all objects that survived are migrated to an older generation memory pool. The idea is that many objects are transient and can quickly be collected and only a handful of objects are long-term objects that live for the entire life of the application. To improve performance this collector assigns memory pools to each thread to let threads allocate new memory blocks without having to coordinate with other threads. Migration of objects from the nursery to the old generation is done by copying the data from the nursery to the old generation pool and updating any live pointers that point to the data to point to the new location. This can be expensive for large objects, so Mono's SGen uses a separate pool of memory for large objects (Large Object Section) and uses a mark-and-sweep algorithm for those objects.[31]

Class library

[edit]The class library provides a comprehensive set of facilities for application development. They are primarily written in C#, but due to the Common Language Specification they can be used by any .NET language. The class library is structured into namespaces, and deployed in shared libraries known as assemblies. Speaking of the .NET Framework is primarily referring to this class library.[33]

Namespaces and assemblies

[edit]Namespaces are a mechanism for logically grouping similar classes into a hierarchical structure. This prevents naming conflicts. The structure is implemented using dot-separated words, where the most common top-level namespace is System, such as System.IO and System.Net. There are other top-level namespaces as well, such as Accessibility and Windows. A user can define a namespace by placing elements inside a namespace block.

Assemblies are the physical packaging of the class libraries. These are .dll files, just like (but not to be confused with) Win32 shared libraries. Examples of assemblies are mscorlib.dll, System.dll, System.Data.dll and Accessibility.dll. Namespaces are often distributed among several assemblies and one assembly can be composed of several files.

Common Language Infrastructure and Common Language Specification

[edit]The Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) as implemented by the Common Language Runtime (CLR), is implemented by the Mono executable. The runtime compiles and executes .NET applications. The common language infrastructure is defined by the ECMA standard.[27] To run an application, you must invoke the runtime with the relevant parameters.

The Common Language Specification (CLS) is specified in chapter 6 of ECMA-335 and defines the interface to the CLI, such as conventions like the underlying types for Enum. The Mono compiler generates an image that conforms to the CLS. This is the Common Intermediate Language. The Mono runtime takes this image and runs it. The ECMA standard formally defines a library that conforms to the CLS as a framework.

Managed and unmanaged code

[edit]Within a native .NET/Mono application, all code is managed; that is, it is governed by the CLI's style of memory management and thread safety. Other .NET or Mono applications can use legacy code, which is referred to as unmanaged, by using the System.Runtime.InteropServices libraries to create C# bindings. Many libraries which ship with Mono use this feature of the CLI, such as Gtk#.

Mono-specific innovations

[edit]Mono has innovated in some areas with new extensions to the core C# and CLI specifications:

- C# Compiler as a Service (Use the C# compiler as a library).[34]

- C# Interactive Shell.[35]

- SIMD support[36] as part of the Mono.SIMD namespace, where method calls to special vector types are directly mapped to the underlying processor CPU SIMD instructions.

- Full static compilation of .NET code[37] (used on Mono/iPhone, Mono/PS3).

- Mono coroutines (used to implement micro-threading code and continuations, mostly for game developers).[38]

- Assembly injection to live processes.[39]

- Use of LLVM as JIT backend.

- Cxxi and CppSharp direct interop with C++ code and libraries.

In addition, Mono is available on a variety of operating systems and architectures.[40]

System requirements

[edit]Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows 8.1, Windows 10, macOS or Linux

Related projects

[edit]Several projects extend Mono and allow developers to use it in their development environment. These projects include:

Cross-platform:

- Banshee Media Player (stalled), a cross-platform music media player built with Mono and Gtk# and also a driver of dozens of C#-based libraries and projects for media handling.

- Beagle (unmaintained), a search system for Unix systems.

- Gecko#, bindings for embedding the layout engine used in Mozilla (Gecko).

- Gtk#, C# wrappers around the underlying GTK and GNOME libraries, written in C and available on Linux, MacOS and Windows.

- Mono Migration Analyzer (MoMA), a tool which aids Windows .NET developers in finding areas in their code that might not be cross-platform and therefore not work in Mono on Linux and other Unixes. Not upgraded since Mono 2.8 (2013); use Microsoft's .NET Portability Analyzer (dotnet-apiport) instead.

- MonoCross, a cross-platform model–view–controller (MVC) design pattern where the Model and Controller are shared across platforms and the Views are unique for each platform for an optimized User Interface. The framework requires Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android.

- MvvmCross, a cross-platform model–view–viewmodel (MVVM) framework utilizing Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android for developing mobile apps.

- MonoDevelop an open-source and cross-platform integrated development environment that supports building applications for ASP.NET, Gtk#, Meego, MonoTouch and Silverlight/Moonlight.

- Moonlight (discontinued), an implementation of Silverlight that uses Mono.

- OpenTK, a managed binding for OpenGL, OpenCL and OpenAL.

- QtSharp, C# bindings for the Qt framework.

- Resco MobileBusiness, a cross-platform developer solution for mobile clients.

- Resco MobileCRM, a cross-platform developer solution for mobile clients synchronized with Microsoft Dynamics CRM.

- ServiceStack a high-performance open-source .NET REST web services framework that simplifies the development of XML, JSON and SOAP web services.

- SparkleShare an open-source client software that provides cloud storage and file synchronization services.

- Tao (superseded by OpenTK), a collection of graphics and gaming bindings (OpenGL, SDL, GLUT, Cg).

- Xwt, a GUI toolkit that maps API calls to native platform calls of the underlying platform, exposing one unified API across different platforms and making possible for the graphical user interfaces to have native look and feel on different platforms. It enables building GUI-based desktop applications that run on multiple platforms, without having to customizing code for different platforms. Xwt API is mapped to a set of native controls on each supported platform. Features that are not available on specific platforms are emulated by using native widgets, which is referred to as hosting in the Xwt context.[41] Xwt was partially used as GUI toolkit (beside GTK#) in the development of the Xamarin Studio.[42] Supported "backend" engines are: WPF engine and Gtk engine (using Gtk#) on Windows, Cocoa engine (using MonoMac) and Gtk engine (using Gtk#) on Mac OS X, and Gtk engine (using Gtk#) on Linux.[43]

macOS:

- Cocoa# – wrappers around the native macOS toolkit (Cocoa) (deprecated).

- Monobjc – a set of bindings for macOS programming.

- MonoMac – newer bindings for macOS programming, based on the MonoTouch API design.

Mobile platforms:

- MonoDroid. Mono for the Android operating system. With bindings for the Android APIs.

- MonoTouch. Mono for the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touches. With bindings to the iOS APIs.

Windows:

- MonoTools for Visual Studio A Visual Studio plugin that allows Windows developers to target Linux and macOS right from Visual Studio and integrates with SUSE Studio.

Other implementations

[edit]Microsoft has a version of .NET 2.0 now available only for Windows XP, called the Shared Source CLI (Rotor). Microsoft's shared source license may be insufficient for the needs of the community (it explicitly forbids commercial use).

Free Software Foundation's decommissioned Portable.NET project.[44]

MonoDevelop

[edit]MonoDevelop is a free integrated development environment primarily designed for C# and other .NET languages such as Nemerle, Boo, and Java (via IKVM), although it also supports languages such as C, C++, Python, and Vala. MonoDevelop was originally a port of SharpDevelop to Gtk#, but it has since evolved to meet the needs of Mono developers. The IDE includes class management, built-in help, code completion, Stetic (a GUI designer), project support, and an integrated debugger.

The MonoDoc browser provides access to API documentation and code samples. The documentation browser uses wiki-style content management, allowing developers to edit and improve the documentation.

Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android

[edit]Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android, both developed by Xamarin, were implementations of Mono for iPhone and Android-based smartphones. Previously available only for commercial licensing,[45] after Microsoft's acquisition of Xamarin in 2016, the Mono runtime itself was relicensed under MIT license[46] and both Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android are being made free and open-source.[47]

Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android reached end-of-life on May 1, 2024, being integrated directly into .NET.[48][49] Microsoft recommends migration to .NET MAUI.[49]

Xamarin.iOS

[edit]Xamarin.iOS (previously named MonoTouch) was a library that allows developers to create C# and .NET based applications that run on the iPhone, iPod and iPad devices. It was based on the Mono framework and developed in conjunction with Novell. Unlike Mono applications, Xamarin.iOS "Apps" were compiled down to machine code targeted specifically at the Apple iPhone and iPad.[50] This is necessary because the iOS kernel prevents just-in-time compilers from executing on the device.

The Xamarin.iOS stack was made up of:

- Compilers

- C# from the Mono Project

- Third-party compilers like RemObject's Oxygene could target Xamarin.iOS also

- Core .NET libraries

- Development SDK:

- Linker – was used to bundle only the code used in the final application

- mtouch – the Native compiler and tool used to deploy to the target device

- Interface Builder integration tools

- Libraries that bind the native CocoaTouch APIs

- Xamarin Studio IDE

Xamarin Studio was used as the primary IDE, however additional links to Xcode and the iOS simulator have been written.

From April to early September 2010, the future of MonoTouch was put in doubt as Apple introduced new terms for iPhone developers that prohibited them from developing in languages other than C, C++ and Objective-C, and the use of a middle layer between the iOS platform and iPhone applications. This made the future of MonoTouch, and other technologies such as Unity, uncertain.[51] Then, in September 2010, Apple rescinded this restriction, stating that they were relaxing the language restrictions that they had put in place earlier that year.[52][53]

Version history

[edit]| Date | Version | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| September 14, 2009 | MonoTouch 1.0[54] | Initial release |

| April 5, 2010 | MonoTouch 2.0[55] | iPad support |

| April 16, 2010 | MonoTouch 3.0[56] | iPhone 4 support |

| April 6, 2011 | MonoTouch 4.0[57] | iOS 4 support |

| October 12, 2011 | MonoTouch 5.0[58] | iOS 5 support |

| September 19, 2012 | MonoTouch 6.0[59] | iOS 6 support |

| February 20, 2013 | Xamarin.iOS 6.2[60] | Visual Studio support |

| July 24, 2013 | Xamarin.iOS 6.4[61] | .NET 4.5 async/await support |

| June 19, 2013 | Xamarin.iOS 7.0[62] | XCode 5 and iOS 7 support |

| September 10, 2014 | Xamarin.iOS 8.0[63] | iOS 8 and Xcode 6 support |

| September 16, 2015 | Xamarin.iOS 9.0[64] | iOS 9 and Xcode 7 support |

| September 13, 2016 | Xamarin.iOS 10.0[65] | iOS 10 and Xcode 8 support |

| September 19, 2017 | Xamarin.iOS 11.0[66] | iOS 11 and Xcode 9 support |

| September 14, 2018 | Xamarin.iOS 12.0[67] | iOS 12 and Xcode 10 support |

| September 13, 2019 | Xamarin.iOS 13.0[68] | iOS 13 and Xcode 11 support |

| September 20, 2020 | Xamarin.iOS 14.0[69] | iOS 14 and Xcode 12 support |

Xamarin.Android

[edit]Xamarin.Android (formerly known as Mono for Android), initially developed by Novell and continued by Xamarin, was a proprietary[citation needed][70] implementation of Mono for Android-based smart-phones.[71][72][73] It was first released on April 6, 2011.[74] Mono for Android was developed to allow developers to more easily write cross-platform applications that will run on all mobile platforms.[75] In an interview with H-Online, Miguel de Icaza stated, "Our vision is to allow developers to reuse their engine and business logic code across all mobile platforms and swapping out the user interface code for a platform-specific API."[76]

In August 2010, a Microsoft spokesman, Tom Hanrahan of Microsoft's Open Source Technology Centre, stated, in reference to the lawsuit filed by Oracle against Google over Android's use of Java, that "The type of action Oracle is taking against Google over Java is not going to happen. If a .NET port to Android was through Mono it would fall under the Microsoft Community Promise Agreement."[77][78]

The Xamarin.Android stack consisted of the following components:

- Mono runtime

- An Android UI designer[79]

- Libraries:

- Core .NET class libraries

- Libraries that bind the native Android/Java APIs

- SDK tools to package, deploy and debug

- Xamarin Studio and Visual Studio 2010 integration to design the UI, remotely debug, and deploy.

Mono on macOS

[edit]CocoaSharp

[edit]Cocoa# (also known as CocoaSharp) was a bridge framework for Mac OS X, which allowed applications developed with the Mono runtime to access the Cocoa API. It was initially released on August 12, 2004,[80] and was included with the Mono distribution starting with version 1.0.6, released on February 18, 2005.[citation needed] It has not seen any development since 2008,[citation needed] and is now deprecated.[81]

Monobjc

[edit]Monobjc was CocoaSharp's replacement. It allows .NET developers to use most of the Mac OS X API, including Cocoa, with no native code, while still achieving a native UI.[citation needed]

Xamarin.Mac

[edit]Xamarin.Mac is a library that allows developers to run .NET and C# apps on the Mac.[82]

License

[edit]Mono is dual licensed by Xamarin, similar to other products such as Qt and the Mozilla Application Suite. Mono's C# compiler and tools are released under the GNU General Public License (GPLv2 only) (starting with version 2.0 of Mono, the Mono C# compiler source code is also available under the MIT X11 License),[83] the runtime libraries under the GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPLv2 only) and the class libraries under the MIT License. These are all free software and open-source licenses and hence Mono is free and open-source software.

The license of the C# compiler was changed from the GPL to the MIT X11 license[84] to allow the compiler code to be reused in a few instances where the GPL would have prevented such:

- Mono's Compiler as a Service

- The Mono interactive Shell

- The Mono embeddable C# compiler

- Mono's implementation of the C# 4.0 dynamic binder.

- MonoDevelop's built-in parser and AST graph

On March 18, 2016, Microsoft's acquisition of Xamarin was officially closed.[85] On March 31, 2016, Microsoft announced at Microsoft Build that they'll completely re-license Mono under the MIT License even in scenarios where previously a commercial license was necessary,[86] and Microsoft stated that they won't assert any "applicable patents" against parties that are "using, selling, offering for sale, importing, or distributing Mono."[87][88] It was also announced that Xamarin had contributed the Mono Project to the .NET Foundation.[87]

Mono and Microsoft's patents

[edit]On July 6, 2009, Microsoft announced that it was placing their ECMA 334 and ECMA 335 specifications under their Community Promise pledging that they would not assert their patents against anyone implementing, distributing, or using alternative implementations of .NET.[89] Mono's implementation of those components of the .NET stack not submitted to the ECMA for standardization has been the source of patent violation concerns for much of the life of the project.[90] In particular, discussion has taken place about whether Microsoft could destroy the Mono project through patent suits.[91]

The base technologies submitted to the ECMA, and therefore also the Unix/GNOME-specific parts, are claimed to be safe due to Microsoft's explicitly placing both ECMA 334 (C#) and ECMA 335 (CLI) standards under the Microsoft Community Promise. The concerns primarily relate to technologies developed by Microsoft on top of the .NET Framework, such as ASP.NET, ADO.NET and Windows Forms (see non-standardized namespaces), i.e. parts composing Mono's Windows compatibility stack. These technologies are today[when?] not fully implemented in Mono and not required for developing Mono-applications, they are simply there for developers and users who need full compatibility with the Windows system.

In June 2009 the Ubuntu Technical Board stated that it saw "no reason to exclude Mono or applications based upon it from the archive, or from the default installation set."[92]

The Free Software Foundation's Richard Stallman has stated on June 2, 2009, that "[...] we should discourage people from writing programs in C#. Therefore, we should not include C# implementations in the default installation of GNU/Linux distributions or in their principal ways of installing GNOME".[93] On July 1, 2009, Brett Smith (also from the FSF) stated that "Microsoft's patents are much more dangerous: it's the only major software company that has declared itself the enemy of GNU/Linux and stated its intention to attack our community with patents.", "C# represents a unique threat to us" and "The Community Promise does nothing to change any of this".[94]

Fedora Project Leader Paul Frields has stated, "We do have some serious concerns about Mono and we'll continue to look at it with our legal counsel to see what if any steps are needed on our part", yet "We haven't come to a legal conclusion that is pat enough for us to make the decision to take mono out".[95]

In November 2011 at an Ubuntu Developer Summit, developers voted to have the Mono-based Banshee media player removed from Ubuntu's default installation beginning on Ubuntu 12.04; although reported reasonings included performance issues on ARM architecture, blocking issues on its GTK+ 3 version, and it being, in their opinion, "not well maintained", speculation also surfaced that the decision was also influenced by a desire to remove Mono from the base distribution, as the remaining programs dependent on Mono, gbrainy and Tomboy, were also to be removed. Mono developer Joseph Michael Shields defended the performance of Banshee on ARM, and also the claims that Banshee was not well-maintained as being a "directed personal insult" to one of its major contributors.[96]

Software developed with Mono

[edit]

Many programs covering a range of applications have been developed using the Mono application programming interface (API) and C#. Some programs written for the Linux Desktop include Banshee, Beagle, F-Spot, Gbrainy, Docky/GNOME Do, MonoTorrent, Pinta, and Tomboy. The program, Logos 5 Bible Study Software (OS X Version), was written for the MacOS.

A number of video games, such as The Sims 3 and Second Life (for their scripting languages), OpenSimulator virtual world server, or games built with the Unity or MonoGame game engines, also make use of Mono.[97] OpenRA bundles its Apple Disk Image and Linux AppImages with Mono essentially removing almost all dependencies from the game.[98]

Version history

[edit]| Date | Version[100] | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| June 30, 2004 | 1.0[101] | C# 1.0 support |

| September 21, 2004 | 1.1[102] | |

| November 9, 2006 | 1.2[103] | C# 2.0 support |

| October 6, 2008 | 2.0[104] | Mono's APIs are now in par with .NET 2.0. Introduces the C# 3.0 and Visual Basic 8 compilers. New Mono-specific APIs: Mono.Cecil, Mono.Cairo and Mono.Posix. Gtk# 2.12 is released. The Gendarme verification tool and Mono Linker are introduced. |

| January 13, 2009 | 2.2[105] | Mono switches its JIT engine to a new internal representation[106] that gives it a performance boost and introduces SIMD support in the Mono.Simd[36] Mono.Simd namespace. Mono introduces Full Ahead of Time compilation that allows developers to create full static applications and debuts the C# Compiler as a Service[34] and the C# Interactive Shell[35] (C# REPL) |

| March 30, 2009 | 2.4[107] | This release mostly polishes all the features that shipped in 2.2 and became the foundation for the Long-Term support of Mono in SUSE Linux. |

| December 15, 2009 | 2.6[108] | The Mono runtime is now able to use LLVM as a code generation backend and this release introduces Mono co-routines, the Mono Soft Debugger and the CoreCLR security system required for Moonlight and other Web-based plugins. On the class library System.IO.Packaging, WCF client, WCF server, LINQ to SQL debut. The Interactive shell supports auto-completion and the LINQ to SQL supports multiple database backends. The xbuild build system is introduced. |

| September 22, 2010 | 2.8[109] | Defaults to .NET 4.0 profile, C# 4.0 support, new generational garbage collector, includes Parallel Extensions, WCF Routing, CodeContracts, ASP.NET 4.0, drops the 1.0 profile support; the LLVM engine tuned to support 99.9% of all generated code, runtime selectable llvm and gc; incorporates Dynamic Language Runtime, MEF, ASP.NET MVC2, OData Client open-source code from Microsoft;. Will become release 3.0 |

| February 15, 2011 | 2.10[110] | |

| October 18, 2012 | 3.0[111] | C# 5.0 support, async support, Async Base Class Library Upgrade and MVC4 - Partial, no async features support. |

| July 24, 2013 | 3.2[112] | Default Garbage Collector is now the SGEN, instead of Boehm |

| March 31, 2014 | 3.4[113] | |

| August 12, 2014 | 3.6[114] | |

| September 4, 2014 | 3.8[115] | |

| October 4, 2014 | 3.10[116] | |

| January 13, 2015 | 3.12[117] | |

| April 29, 2015 | 4.0[118] | Defaults to .NET 4.5 profile and ships only .NET 4.5 assemblies, defaults to C# 6.0. First release to integrate Microsoft open-source .NET Core code |

| May 10, 2017 | 5.0[119] | Shipping Roslyn C# compiler to enable C#7 support; Shipping msbuild and deprecating xbuild for better compatibility; Enabling concurrent SGen garbage collector to reduce time spent in GC; Introducing the AppleTLS stack on macOS for HTTPS connections; Continued Progress on .NET Class Library convergence; Updated libjpeg in macOS package |

| July 14, 2017 | 5.2[120] | Support for .NET Standard 2.0, strong assembly names, and experimental default interface members. |

| October 5, 2017 | 5.4[121] | The JIT Runtime now supports concurrent method compilation and various other Performance Optimisations; Added .NET 4.7 reference assemblies |

| February 1, 2018 | 5.8[122] | Initial WebAssembly port; Modes for the SGen GC; Includes Roslyn's csi (C# interactive) REPL tool |

| February 26, 2018 | 5.10[123] | The Interpreter is now included in the default installation; runtime now supports Default Interface Methods; WebAssembly considered reliable now; Support for .NET 4.7.1 / C# 7.2 / F# 4.1 |

| May 8, 2018 | 5.12[124] | Port to IBM AIX/i; now includes VB.NET compiler; option to use jemalloc |

| August 7, 2018 | 5.14[125] | Major Windows.Forms update to improve compatibility with .NET |

| October 8, 2018 | 5.16[126] | Hybrid suspend garbage collector; Client certificate support; C# 7.3 support |

| December 21, 2018 | 5.18[127] | .NET 4.7.2 support; more CoreFX code is used |

| April 11, 2019 | 5.20[128] | SSPI (Security Support Provider Interface) in System.Data assembly; Various issues resolved |

| July 17, 2019 | 6.0[129] | C# compiler defaults to version C# 8.0 RC; Various stability improvement in debugger support; Mono Interpreter is feature complete and stable |

| September 23, 2019 | 6.4[130] | C# compiler support for C# 8 language version; .NET Standard 2.1 support |

| December 10, 2019 | 6.6[131] | Added .NET 4.8 reference assemblies |

| January 15, 2020 | 6.8[132] | Various Bugfixes |

| May 19, 2020 | 6.10[133] | Various Bugfixes |

| November 24, 2020 | 6.12[134] | Various Bugfixes |

| March 4, 2025 | 6.14[135] | First release after transfer to WineHQ |

See also

[edit]- Common Language Runtime

- .NET Framework

- .NET, an open-source framework and successor to .NET Framework

- Standard Libraries (CLI)

- Base Class Library (BCL)

- Comparison of application virtual machines

- DotGNU – A free software umbrella project which includes Portable.NET

- MonoDevelop – An open-source IDE targeting both Mono and Microsoft .NET Framework platforms

- Moonlight (runtime), an open-source implementation of Microsoft's Silverlight developed by the Mono Project

- Shared Source Common Language Infrastructure – Microsoft's shared source implementation of .NET, formerly codenamed Rotor

- mod_mono – A module for the Apache HTTP Server that allows hosting of ASP.NET pages and other assemblies on multiple platforms by use of Mono

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Introducing Mono on AIX and IBM i

- ^ "FAQ: Licensing". Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Microsoft to acquire Xamarin and empower more developers to build apps on any device". Official Microsoft Blog. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ^ a b Sourav, Rudra (2024-09-02). "Microsoft's Unexpected Move to Hand Over an Open-Source Project to the Wine Team: A Generous Shift?". It's FOSS News. Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- ^ Bonisteel, Steven (June 23, 2000). "Microsoft sees nothing but .NET ahead". ZDNet. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "ECMA-335-Part-I-IV - ECMA-335, 1st edition, December 2001" (PDF).

- ^ Wilcox, Joe; Shankland, Stephen (June 28, 2001). "Microsoft edges into sharing code". ZDNet.

- ^ "[Mono-list] Mono early history". mono-list (Mailing list). 2003-10-13. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2005-03-30.

- ^ "OSS .NET implementation Mono 1.0 released - Ars Technica". ArsTechnica. 30 June 2004. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ^ "Supported Platforms". Mono website.

- ^ Koep, Paul (2011-05-02). "Employees say hundreds laid off at Novell's Provo office". KSL-TV. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2011-05-04). "Is Mono dead? Is Novell dying?". ZDNet. Retrieved 2024-08-02.

- ^ Clarke, Gavin (2011-05-03). ".NET Android and iOS clones stripped by Attachmate". The Register. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ^ "Announcing Xamarin - Miguel de Icaza". Tirania.org. 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "The Death and Rebirth of Mono". infoq.com. 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

Even if they aren't supporting it, they do own a product that is in direct competition with Xamarin's future offerings. Without some sort of legal arrangement between Attachmate and Xamarin, the latter would face the daunting prospect of proving that their new development doesn't use any the technology that the old one did. Considering that this is really just a wrapper around the native API, it would be hard to prove you had a clean-room implementation even for a team that wasn't intimately familiar with Attachmate's code.

- ^ "SUSE and Xamarin Partner to Accelerate Innovation and Support Mono Customers and Community". Novell. 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

The agreement grants Xamarin a broad, perpetual license to all intellectual property covering Mono, MonoTouch, Mono for Android and Mono Tools for Visual Studio. Xamarin will also provide technical support to SUSE customers using Mono-based products, and assume stewardship of the Mono open source community project.

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel (2011-07-18). "Novell/Xamarin Partnership around Mono". Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- ^ "Microsoft to acquire Xamarin and empower more developers to build apps on any device". Official Microsoft Blog. February 24, 2016. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ a b de Icaza, Miguel (2011-03-07). "GDC 2011". Retrieved 2011-03-11.

We have no plans on building WPF. We just do not have the man power to build an implementation in any reasonable time-frame(...)For tools that are mostly OpenGL/DirectX based, use Windows.Forms, keeping in mind that some bug fixing or work around on their part might be needed as our Windows.Forms is not actively developed.

- ^ "Mono compatibility list".

- ^ "Mono Project Roadmap - Mono". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "MoonlightRoadmap". Mono Team. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ "Releasing Moonlight 2, Roadmap to Moonlight 3 and 4 — Miguel de Icaza". Tirania.org. 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Moonlight 3.0 Preview 1 — Miguel de Icaza". Tirania.org. 2010-02-03. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Xamarin abandons its Silverlight for Linux technology". ZDNet.

- ^ a b "Ecma-335".

- ^ "Technet.com". Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Database Access - Mono".

- ^ "Mono LLVM". Mono.

- ^ a b "Compacting GC". mono-project.com. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Boehm, Hans-J. "Advantages and Disadvantages of Conservative Garbage Collection". Xerox PARC. Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ ".NET Framework Architecture". official Mono documentation.

- ^ a b "Mono's C# Compiler as a Service on Windows. - Miguel de Icaza". Tirania.org. 2010-04-27. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ a b "CsharpRepl - Mono". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ a b "Mono's SIMD Support: Making Mono safe for Gaming - Miguel de Icaza". Tirania.org. 2008-11-03. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel. "Static Compilation in Mono".

- ^ "Continuations - Mono".

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel. "Monovation: Assembly Injection into Live Processes".

- ^ "Supported Platforms - Mono".

- ^ Narayanaswamy, Anand (23 Nov 2012). "Build Cross Platform Applications with Xwt". InfoQ. Archived from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel (22 February 2013). "The Making of Xamarin Studio". InfoQ. Archived from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ "Xwt Read Me". Xwt on GitHub. 15 Jan 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ "DotGNU Project". Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "FAQ". os.xamarin.com. 2011-08-01.

MonoTouch is a commercial product based on the open source Mono project and is licensed on a per-developer basis.

- ^ "Mono relicensed MIT". www.mono-project.com. 2016-03-31.

- ^ "Xamarin for Everyone". blog.xamarin.com. 2016-03-31. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

we are announcing today our commitment to open source the Xamarin SDKs for Android, iOS, and Mac under the MIT license in the coming months

- ^ "The official Xamarin support policy". dotnet.microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved January 26, 2026.

- ^ a b "Xamarin". dotnet.microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved January 26, 2026.

- ^ "MonoTouch and iPhone 4".

Applications built with MonoTouch are native applications indistinguishable from other native applications.

- ^ "Apple takes aim at Adobe… or Android?". 9 April 2010.

- ^ "Statement by Apple on App Store Review Guidelines".

Based on their input, today we are making some important changes to our iOS Developer Program license in sections 3.3.1, 3.3.2 and 3.3.9 to relax some restrictions we put in place earlier this year. In particular, we are relaxing all restrictions on the development tools used to create iOS apps, as long as the resulting apps do not download any code. This should give developers the flexibility they want, while preserving the security we need.

- ^ "Great News for MonoTouch Users".

With these new terms, the ambiguity is gone and C# lovers and enthusiasts can go back to using MonoTouch. Developers that like garbage collection and their strongly typed languages can resume their work.

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel. "MonoTouch 1.0 goes live".

- ^ "MonoTouch 2.0.0". Xamarin.

- ^ "MonoTouch 3.0.0". Xamarin.

- ^ "MonoTouch 4.0.0". Xamarin.

- ^ "MonoTouch 5.0". Xamarin.

- ^ "MonoTouch 6.0". Xamarin.

- ^ "Xamarin.iOS 6.2". Xamarin. 28 January 2023.

- ^ "Xamarin.iOS 6.4". Xamarin. 8 July 2022.

- ^ "iOS 7 and Xamarin: Ready When You Are". Xamarin Blog. 2013-09-18. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ "iOS 8 Bigger and Better with Xamarin". Xamarin Blog. 2014-09-10. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ "Xamarin for iOS 9: Search Deeper". Xamarin Blog. 2015-09-16. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ "Major Updates: iOS 10, Android Nougat, and Other Tasty Bits". Xamarin Blog. 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ spouliot (19 September 2017). "Xamarin.iOS 11.0 Release Notes - Xamarin". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ spouliot (14 September 2018). "Xamarin.iOS 12.0 Release Notes - Xamarin". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ spouliot (13 September 2019). "Xamarin.iOS 13.0 Release Notes - Xamarin". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ spouliot (21 September 2020). "Xamarin.iOS 14.0 Release Notes - Xamarin". docs.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ "How is Mono for Android licensed?". Mono for Android FAQ. 2011-08-28. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ "Novell's Mono project bringing .Net development to Android". NetworkWorld.

- ^ "Novell's Mono project bringing .Net development to Android". InfoWorld. 16 March 2010.

- ^ "MonoDroid: .NET Support Coming to Android". TechieBuzz. 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Mono for Android brings C# to Android". Heise Online. 2011-04-07. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ^ "Novell (Mono/C#) is developing MonoDroid". Android Community. 18 February 2010.

This will make it easier for developers to make cross platform apps as well as bring some of the existing apps that are made using MonoTouch to Android.

- ^ "Mono for Android". H-Online.

Our vision is to allow developers to reuse their engine and business logic code across all mobile platforms and swapping out the user interface code for a platform-specific API.

- ^ "Microsoft won't stop (Mono) .NET on Android". TechWorld.

The type of action Oracle is taking against Google over Java is not going to happen. If a .NET port to Android was through Mono it would fall under the Microsoft Community Promise Agreement.

- ^ "Microsoft says .NET on Android is safe, no litigation like Oracle". Developer Fusion.

- ^ "Xamarin Designer for Android". Visual Studio Magazine.

On May 14, Xamarin announced Mono for Android 4.2.

- ^ "Cocoa# is Shaping up; First Screenshots Available – OSnews".

- ^ "macOS | Mono". www.mono-project.com. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ^ davidortinau. "Xamarin.Mac - Xamarin". learn.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2023-02-04.

- ^ "Mono C# Compiler Under MIT X11 License". Novell Inc. 2008-04-08. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ de Icaza, Miguel. "Mono C# compiler now also MIT X11 licensed".

- ^ "Xamarin for Everyone". Xamarin Blog. Xamarin. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ Anderson, Tim (31 March 2016). "Microsoft to make Xamarin tools and code free and open-source". The Register.

- ^ a b Ferraira, Bruno (31 March 2016). "Xamarin now comes free with Visual Studio". The Tech Report.

- ^ "Microsoft Patent Promise for Mono". Mono on GitHub. Mono Project. 2016-03-28. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ "The ECMA C# and CLI Standards". Port 25. July 6, 2009. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

Under the Community Promise, Microsoft provides assurance that it will not assert its Necessary Claims against anyone who makes, uses, sells, offers for sale, imports, or distributes any Covered Implementation under any type of development or distribution model, including open-source licensing models such as the LGPL or GPL.

- ^ Babcock, Charles (August 7, 2001). "Will open source get snagged in .Net?". ZDNet Asia. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Brett (July 16, 2009). "Microsoft's Empty Promise". fsf.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Mono Position Statement". Canonical Ltd. June 30, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

It is common practice in the software industry to register patents as protection against litigation, rather than as an intent to litigate. Thus mere existence of a patent, without a claim of infringement, is not sufficient reason to warrant exclusion from the Ubuntu Project.

- ^ "Why free software shouldn't depend on Mono or C#". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Microsoft's Empty Promise". Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Fedora is concerned about Mono". internetnews.com. June 12, 2009. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

We haven't come to a legal conclusion that is pat enough for us to make the decision to take mono out

- ^ "'Bansheegeddon' may see Banshee, Mono dropped from Ubuntu default". ITWorld. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "Companies using Mono". Mono-project. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Paul Chote: OpenRA: Playtest 20190825, 2019-08-25

- ^ "Mono Releases". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "OldReleases". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Mono 1.0 Release Notes". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Mono 1.1.1: Development Release". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Mono 1.2: Release Notes". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.0". Mono-project.com. 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.2". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Linear IR - Mono". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.4". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.6". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.8". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 2.10". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.0". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.2". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.4". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.6". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.8". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.10". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 3.12". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 4.0". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ "Release Notes Mono 5.0". Mono-project.com. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ "Mono 5.2.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.4.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.8.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.10.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.12.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.14.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.16.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.18.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 5.20.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.0.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.4.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.6.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.8.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.10.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Mono 6.12.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "mono-6.14.0 Mono / Framework Mono GitLab".

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from Mono's homepage, which was then under the GNU Free Documentation License.

- de Icaza, Miguel (October 13, 2003). "[Mono-list] Mono early history.". mono-list (Mailing list). Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2005.

- Dumbill, Edd (March 11, 2004). "Will Mono Become the Preferred Platform for Linux Development?". ONLamp. Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- Loli-Queru, Eugenia (February 22, 2005). "Mono Applications? Aplenty!". OSNews. Retrieved December 6, 2005.

- Kerner, Sean Michael (November 18, 2005). "Mono Project Goes Virtual". Internet News. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- Kerner, Sean Michael (November 9, 2006). "Months Late, Novell Ships Mono 1.2". internetnews.com.

- Northcutt, Corey (October 12, 2006). "In the World of mod_mono". Ubiquity. Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- Campbell, Sean (October 8, 2008). "Interview with Joseph Hill - Product Manager - Mono - Novell". How Software is Built. Microsoft. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2025.

- Smith, Tim (September 9, 2010). "A Brief Introduction to the Java and .NET Patent Issues". InfoQ. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- MonoTouch Main Page for the port to Apple Inc.'s hand-held products

Mono (software)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Early Development

The Mono project originated at Ximian, a company co-founded by Miguel de Icaza and Nat Friedman, as an effort to implement an open-source version of Microsoft's .NET Framework, specifically targeting the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) and C# specifications for non-Windows platforms like Linux.[15] De Icaza, already known for co-creating the GNOME desktop environment, initiated the project following the public release of .NET documentation in December 2000, viewing it as an opportunity to enable cross-platform development with modern languages and tools.[16] The initiative was driven by the goal of fostering a free software ecosystem compatible with .NET, leveraging ECMA-standardized components to avoid proprietary dependencies.[4] The project was formally announced on June 30, 2001, during de Icaza's presentation at the O'Reilly Open Source Convention (OSCON), where Ximian outlined plans for a runtime, C# compiler, and class libraries to support .NET applications on Unix-like systems.[17] Initial development emphasized rapid prototyping, with a small team including de Icaza focusing on core components. By August 28, 2001, the Mono runtime executed its first "Hello World" program, processing 1821 Common Intermediate Language (CIL) instructions across 12 classes.[4] On September 5, 2001, the self-written C# compiler (mcs) compiled a basic program on Windows using Microsoft's runtime, producing an executable that ran on Linux, demonstrating early cross-platform viability.[4] Subsequent milestones in late 2001 included the release of Mono 0.7 on September 18, providing initial compiler and runtime functionality, and the C# compiler achieving self-compilation on Linux by November 14.[4] Key early contributors comprised Paolo Molaro for runtime optimization, Dietmar Maurer for just-in-time compilation, Dick Porter for class library foundations, and Sergey Lukyanov for metadata handling.[4] By 2002, the compiler advanced to full self-hosting: bootstrapping with the .NET runtime on January 3, operating independently on Linux by March 12, and compiling the core mscorlib library by June 30, marking a foundational step toward a complete, independent .NET-compatible stack under Ximian's stewardship.[4]Novell Acquisition and Expansion

Novell acquired Ximian, the primary sponsor of the Mono project, on August 4, 2003, for an undisclosed sum, integrating Mono's development into its broader Linux and open-source strategy.[18] This move positioned Mono as a key component for enabling .NET compatibility on Linux, with Novell committing resources to accelerate its maturation into a viable enterprise alternative to Microsoft's .NET Framework.[19] Following the acquisition, Novell expanded Mono's development team from five engineers at Ximian to 20 dedicated staff, fostering contributions from a community of approximately 300 to 400 developers.[20] This investment supported the release of Mono 1.0 on June 30, 2004, marking the project's first stable version with a runtime environment, C# compiler, and core class libraries compliant with ECMA standards.[21] The release emphasized cross-platform interoperability, allowing .NET applications to run on Linux while enabling developers to target multiple environments from a single codebase.[22] Under Novell, Mono saw integration into enterprise products, including SUSE Linux Enterprise, with plans announced in 2008 to include Mono 2.0 in SUSE Linux Enterprise 11 for running .NET applications natively on Linux servers.[23] Novell also developed commercial extensions, such as Mono Tools for Visual Studio in 2009, which allowed .NET developers to build and debug Linux-targeted applications within Microsoft's IDE.[24] These efforts prioritized enterprise features like Windows Forms support, enhancing Mono's appeal for porting Windows applications to open-source platforms.[25]Xamarin and Microsoft Integration

Xamarin was founded in May 2011 by Miguel de Icaza and other former Mono developers following the acquisition of Novell by Attachmate, which discontinued active development of Mono and related projects.[26] The company leveraged the Mono runtime to create cross-platform mobile development tools, including Xamarin.iOS (previously MonoTouch) for iOS applications and Xamarin.Android (previously Mono for Android) for Android, enabling C# and .NET-based app development on non-Windows platforms.[27] These tools used Mono's just-in-time (JIT) compiler and ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation to address platform-specific restrictions, such as Apple's ban on JIT on iOS devices.[8] On February 24, 2016, Microsoft announced an agreement to acquire Xamarin, integrating its technology into the Visual Studio ecosystem to enhance cross-platform development for Windows, Android, and iOS.[28] The acquisition positioned Microsoft as the steward of the Mono Project, with Xamarin obtaining a perpetual license to Mono's intellectual property prior to the deal.[8] Post-acquisition, Microsoft relicensed Mono under the MIT License to broaden its adoption and aligned it with emerging .NET initiatives, while making Xamarin tools freely available to reduce barriers for developers.[29] Integration efforts included embedding Xamarin capabilities directly into Visual Studio, such as Xamarin Studio rebranded as Visual Studio for Mac announced on November 16, 2016, and improved support for Mono-based workloads in Unity game development.[17] Microsoft's stewardship maintained Mono's role in scenarios requiring full .NET Framework compatibility on Linux and macOS, distinct from the newer cross-platform .NET Core, though development emphasis shifted toward unifying .NET ecosystems.[1] This move facilitated tighter interoperability between Mono-derived mobile tools and Microsoft's cloud services like Azure, while preserving open-source contributions under community governance.[30]Decline and Transfer to WineHQ

Following the acquisition of Xamarin by Microsoft in February 2016, development focus shifted toward .NET Core, a modular, cross-platform evolution of .NET that rendered the original Mono runtime largely redundant for new applications.[31] Mono's last major upstream release occurred in 2019, after which maintenance stagnated as Microsoft prioritized its dotnet/runtime repository fork for legacy compatibility needs.[32] This transition reflected broader industry movement away from Mono's full-framework emulation toward lightweight, native cross-platform support in .NET 5 and later versions, reducing Mono's relevance for mainstream .NET development.[33] By 2024, Microsoft determined that the upstream Mono project no longer aligned with active development priorities, as most workloads had migrated to modern .NET equivalents.[34] On August 27, 2024, Microsoft announced the donation of the Mono Project to WineHQ, citing synergies with Wine's requirements for executing legacy Windows .NET applications that resist translation to .NET Core due to proprietary or outdated dependencies.[35] Wine, which had long incorporated a Mono variant for .NET interoperability in its Windows compatibility layer, assumed stewardship to sustain support for such edge cases.[36] Under WineHQ's management, the project relocated to GitLab at gitlab.winehq.org/mono/mono, with the first release—version 6.14.0—issued on March 8, 2025, incorporating five years of prior unmerged contributions.[37] This handover ensured continued availability for niche uses, such as Wine's Framework Mono integration, while Microsoft explicitly advised developers to adopt contemporary .NET runtimes over the donated legacy codebase.[35] The move closed a chapter on Mono's role as a pioneering open-source .NET bridge, now preserved primarily for compatibility rather than innovation.[33]Technical Architecture

Core Runtime Components

The Mono runtime serves as the core execution engine, implementing the ECMA Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) standard (ECMA-335) to provide a virtual machine for running managed code across platforms. It handles just-in-time (JIT) and ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation of Common Intermediate Language (CIL) bytecode into native machine code, automatic memory management via garbage collection, assembly loading, and threading support, enabling compatibility with .NET Framework applications on non-Windows systems.[2][38] The JIT compiler dynamically translates CIL instructions to optimized native code at runtime, supporting architectures such as x86, x86-64, ARM, and PowerPC, with features like inlining, loop unrolling, and exception handling tailored for performance on diverse hardware. For scenarios requiring reduced startup latency or static linking—such as mobile or embedded deployments—the AOT compiler pre-compiles assemblies into native executables via commands likemono --aot, producing bundles that merge code, libraries, and runtime elements while allowing full static AOT for self-contained binaries.[38][2]

Garbage collection in Mono defaults to the SGen collector in the mono executable, a precise, generational, and compacting mechanism designed for low-latency server and client workloads, which scans and relocates objects to mitigate fragmentation; alternatively, the Boehm conservative collector is available via mono-boehm for conservative root scanning without relocation, though it may introduce higher memory overhead. The runtime's library loader dynamically resolves and loads assemblies, supporting metadata reflection and interoperability with native code through platform invocation (P/Invoke). Threading primitives align with CLI specifications, providing managed threads with synchronization constructs like monitors and mutexes, integrated with host OS threading models.[38][39][40]

Embedding capabilities allow the runtime to integrate into C/C++ applications, exposing the CLI virtual machine for scripted extensions while reusing existing native infrastructure, with APIs for initialization, assembly execution, and domain isolation to prevent interference between execution contexts. These components collectively ensure portable, verifiable execution of CLI-compliant code, though Mono's implementation deviates from Microsoft's CLR in optimizations and platform-specific adaptations, such as tailored JIT for ARM in mobile contexts.[38][2]

Class Libraries and Compatibility

Mono's class libraries form the foundational assemblies that enable application development and execution, mirroring the structure of Microsoft's .NET Framework base class library (BCL) while prioritizing cross-platform portability. The core library, known as mscorlib, provides essential types for basic operations, including collections, threading, and I/O, implemented primarily in C# within the Mono compiler suite (mcs) module. Additional namespaces such as System, System.Collections, System.IO, and System.Threading replicate .NET equivalents, adhering to ECMA-335 standards for the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) to ensure interoperability. These libraries are organized into assemblies stored in directories corresponding to their namespaces, facilitating modular development and reducing dependencies on platform-specific code.[41] To achieve compatibility, Mono implements profiles that align with various .NET Framework versions, allowing developers to target subsets of the full framework. For instance, Mono's full profile supports most of .NET 4.7 features, encompassing LINQ, Entity Framework compatibility layers, and generic collections, but excludes Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF), Windows Workflow Foundation (WWF), and offers partial support for Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) and asynchronous ASP.NET operations. Earlier profiles, such as those emulating .NET 2.0 or 3.5, enable legacy application porting, with Mono providing Unix-specific extensions like POSIX interop in assemblies such as System.IO.FileSystem. This profiled approach ensures that CIL assemblies compiled against compatible .NET versions can execute on Mono without recompilation, provided they avoid Windows-exclusive APIs like WinForms or DirectX dependencies.[42][42] Binary compatibility between .NET Framework-compiled libraries and Mono is generally high for pure managed code, as both adhere to the same CLI specification; a library targeting .NET Standard or earlier frameworks will load via Mono's runtime if no proprietary Microsoft extensions are invoked. However, discrepancies arise in areas requiring native Windows integrations, such as cryptography providers or registry access, where Mono substitutes cross-platform alternatives, potentially leading to behavioral differences verifiable through runtime profiling tools. Post-2014 Microsoft open-sourcing of .NET Core components, Mono incorporated compatible subsets, enhancing alignment with modern .NET Standard libraries up to version 2.1, though full .NET 5+ equivalence remains partial due to Mono's emphasis on Framework-era support. Developers can verify compatibility using Mono'smcs compiler flags for specific profiles or tools like mono --verify to detect assembly mismatches.[43][44]

Execution Engines and Optimizations

Mono employs a just-in-time (JIT) compiler as its core execution engine, translating Common Intermediate Language (CIL) bytecode from .NET assemblies into native machine code at runtime to enable platform-specific execution. This JIT supports multiple architectures, including x86, ARM, and PowerPC, and operates with configurable optimization levels such as-O=all to enable comprehensive passes like inlining and register allocation.[38]

In addition to JIT, Mono provides ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation, which precompiles assemblies into native code artifacts—such as ELF shared objects on Linux systems—stored alongside the original bytecode files (e.g., assembly.exe.so). The runtime loads these AOT images preferentially over JIT compilation for available methods, reducing initial JIT overhead and enabling code sharing via position-independent code (PIC) mapped with mmap, though PIC incurs a minor performance penalty relative to non-PIC JIT output.[45] [46]

AOT integrates with the JIT in hybrid modes, where unloaded or dynamically generated methods fall back to JIT, but full AOT (--full-aot) disables JIT entirely to comply with runtime restrictions on platforms like iOS, precomputing elements like generic virtual tables to minimize metadata processing. This mode supports platforms limited to x86, AMD64, and ARM, but restricts features requiring dynamic code emission, such as Reflection.Emit or certain LINQ expressions.[45] [46]

Optimizations in both engines include high-level intermediate representation (IR) transformations, loop unrolling, and dead code elimination, with AOT allowing additional passes not feasible in standard JIT due to precompilation, such as full program analysis when combined with profile-guided data. Mono can leverage the LLVM backend for enhanced code generation and optimization in JIT or AOT scenarios via flags like --llvm, improving instruction selection and vectorization on supported hardware. Profile-guided optimization profiles execution to prioritize hot paths, further tuning code layout and inlining decisions.[38] [47]

Differences from Microsoft's .NET

Mono implements the ECMA-334 standard for C# and ECMA-335 for the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI), enabling binary compatibility with .NET Framework assemblies up to version 4.7, but excludes Windows-specific components such as Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF), Windows Workflow Foundation (WWF), and provides only limited support for Windows Communication Foundation (WCF) and asynchronous ASP.NET features.[42] In contrast, Microsoft's .NET Framework incorporates proprietary extensions beyond these ECMA standards, with deep integration into Windows APIs for desktop technologies like WPF and full WCF functionality optimized for Windows environments.[48] The runtime engines diverge significantly: Mono employs its own JIT compiler, which supports a lightweight "mini JIT" for rapid startup or an LLVM-based backend for advanced optimizations, alongside Boehm-Demers-Weiser garbage collection tailored for multi-platform use.[49] Microsoft's .NET implementations use RyuJIT in the CoreCLR runtime (for .NET Core/5+), which features tiered compilation, aggressive inlining, SIMD vectorization, and profile-guided optimizations, often yielding superior performance in benchmarks compared to Mono's engine, particularly for compute-intensive workloads.[50] Mono's design emphasizes a minimal footprint and ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation for scenarios like mobile and embedded devices, where .NET's runtime may require additional configuration for similar deployments.[51] Class libraries in Mono are independent re-implementations of core namespaces (e.g., mscorlib, System, System.Data), achieving compatibility with .NET Standard across all versions and allowing most portable .NET Framework code to run without modification on non-Windows platforms, provided it avoids Windows-exclusive APIs.[42] However, gaps persist in proprietary or platform-dependent areas, such as incomplete emulation of Windows registry access or Active Directory integration, necessitating alternatives like Gtk# for UI or custom providers for data access.[44] Microsoft's .NET libraries, especially in the modern unified .NET platform, include updated, high-performance implementations with broader ecosystem support, including native AOT for reduced startup times and container optimization, which Mono approximates but does not fully match in feature parity or ongoing innovation.[51] Both projects share MIT licensing under the .NET Foundation since Microsoft's acquisition of Xamarin in 2016, but Mono's independent origins enable community-driven extensions for niche uses like Unity scripting, while Microsoft's .NET prioritizes enterprise-scale cloud and web scenarios with official tooling and security updates.[1] Historically, Mono faced scrutiny over potential patent risks from Microsoft's proprietary .NET elements, mitigated by a 2009 community promise not to assert patents against implementers, though this did not cover all extensions.[2]Development Tools and Ecosystem

IDEs and Editors

MonoDevelop served as the primary integrated development environment (IDE) for Mono, initially released in 2005 as a GNOME-oriented IDE built on the Mono runtime and GTK#, supporting C#, ASP.NET, and cross-platform .NET application development on Linux, Windows, and macOS.[52] It featured code completion, refactoring tools, integrated debugging with the Mono runtime, and graphical designers for WinForms and GTK# interfaces.[53] Over time, MonoDevelop evolved through acquisitions: rebranded as Xamarin Studio in 2013 following Xamarin's involvement in mobile development, and later integrated into Visual Studio for Mac in 2016 after Microsoft's acquisition of Xamarin, retaining core Mono compatibility for building and debugging.[17] However, the original MonoDevelop project ceased active maintenance around 2020, with its GitHub repository abandoned by Microsoft earlier that year.[54] Visual Studio for Mac, which inherited MonoDevelop's codebase, provided enhanced Mono support including workload templates for console, GUI, and web apps, but shifted toward .NET Core/.NET 6 by 2022, reducing reliance on the Mono framework.[55] Microsoft retired Visual Studio for Mac entirely on August 31, 2024, recommending alternatives like Visual Studio Code or JetBrains Rider for cross-platform .NET tasks.[56] In contemporary Mono workflows, particularly for legacy projects or embedded uses like Unity (which embeds Mono), Visual Studio Code with the official C# extension (powered by OmniSharp and Roslyn) is widely adopted, offering IntelliSense, debugging, and build integration directly with the Mono runtime on Linux, macOS, and Windows.[57] This setup supports Mono-specific compilation viamcs or mono commands while providing language server protocol features for code navigation and error detection.[58]

General-purpose editors such as Vim or Emacs can handle Mono development through plugins for C# syntax highlighting, OmniSharp integration for autocompletion, and shell integration for invoking Mono tools like mkbundle for standalone executables, though they lack the full IDE debugging and project management of dedicated environments.[58] JetBrains Rider offers another robust option with native support for Mono projects, including runtime selection and cross-platform profiling, suitable for professional development despite not being Mono-exclusive.

Mobile and Cross-Platform Frameworks

Mono's contributions to mobile development originated with MonoTouch, released in 2010, which provided an implementation of the Mono runtime for iOS devices, enabling C# applications to access native iOS APIs while adhering to Apple's ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation requirements due to restrictions on just-in-time (JIT) execution in App Store apps.[59] Similarly, Mono for Android, introduced in 2011, integrated the Mono runtime with the Android platform, allowing managed code to run alongside the Android Runtime (ART) and interact with native Java-based APIs through bindings.[60] These tools formed the foundation for cross-platform mobile app development by permitting code reuse across iOS and Android while generating native performance applications. In 2012, these efforts evolved into the Xamarin platform, which rebranded MonoTouch as Xamarin.iOS and Mono for Android as Xamarin.Android, unifying them under a shared C# codebase for building mobile apps with access to platform-specific features.[61] Xamarin.Android specifically embeds a shared Mono runtime instance for debugging and deployment, supporting both JIT and AOT modes to optimize for device constraints.[62] This architecture allowed up to 90% code sharing between platforms, reducing development time compared to separate native implementations in Objective-C/Swift for iOS and Java/Kotlin for Android.[63] Xamarin.Forms, introduced in 2014, extended Mono's cross-platform capabilities by providing a declarative UI framework for shared user interfaces across iOS, Android, and later Windows, abstracting platform differences while leveraging the underlying Mono runtime for execution.[1] Following Microsoft's 2016 acquisition of Xamarin, these frameworks integrated deeper into the .NET ecosystem, influencing subsequent tools like .NET MAUI, though Mono's runtime remained integral to Xamarin-based deployments until broader .NET unification efforts.[64] Frameworks such as MvvmCross, built atop Xamarin, further utilized Mono for model-view-viewmodel (MVVM) patterns in cross-platform apps, demonstrating its versatility beyond core Xamarin tooling.[1]Related Runtimes and Projects

Microsoft's .NET implementation, encompassing .NET Core and subsequent unified versions from .NET 5 onward, evolved as a cross-platform successor incorporating Mono's contributions for non-Windows environments, including shared runtime components like garbage collection and JIT compilation.[51][1] The dotnet/runtime repository maintains a fork of Mono's source code, integrating it into the broader .NET ecosystem for workloads requiring legacy .NET Framework compatibility on Linux and other platforms.[65] In August 2024, Microsoft transferred stewardship of the original Mono project to WineHQ, enabling enhanced .NET Framework support within Wine for executing Windows-specific .NET applications on Linux without native porting.[35][66] This aligns with Mono's historical role in bridging proprietary Microsoft technologies to open-source systems, though Microsoft now directs developers toward .NET for new projects.[31] Key projects leveraging Mono include Unity, which employs a customized fork of the Mono runtime as its default scripting backend for C# code execution across game consoles, desktops, and mobile devices, prioritizing embeddability and just-in-time compilation.[67] Another is Moonlight, an open-source Silverlight runtime developed by the Mono team to run Silverlight 1.0 through 4.0 content on Unix-like systems, though it is no longer actively maintained.[68][69] These efforts highlight Mono's influence on cross-platform media and game development tools prior to .NET's maturation.Platform Support and Deployment

Linux and Unix-like Systems