Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Compactification (physics)

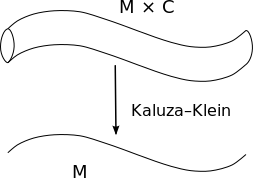

View on WikipediaIn theoretical physics, compactification means changing a theory with respect to one of its space-time dimensions. Instead of having a theory with this dimension being infinite, one changes the theory so that this dimension has a finite length, and may also be periodic.

Compactification plays an important part in thermal field theory where one compactifies time, in string theory where one compactifies the extra dimensions of the theory, and in two- or one-dimensional solid state physics, where one considers a system which is limited in one of the three usual spatial dimensions.

At the limit where the size of the compact dimension goes to zero, no fields depend on this extra dimension, and the theory is dimensionally reduced.

In string theory

[edit]In string theory, compactification is a generalization of Kaluza–Klein theory.[1] It tries to reconcile the gap between the conception of our universe based on its four observable dimensions with the ten, eleven, or twenty-six dimensions which theoretical equations lead us to suppose the universe is made with.

For this purpose it is assumed the extra dimensions are "wrapped" up on themselves, or "curled" up on Calabi–Yau spaces, or on orbifolds. Models in which the compact directions support fluxes are known as flux compactifications. The coupling constant of string theory, which determines the probability of strings splitting and reconnecting, can be described by a field called a dilaton. This in turn can be described as the size of an extra (eleventh) dimension which is compact. In this way, the ten-dimensional type IIA string theory can be described as the compactification of M-theory in eleven dimensions. Furthermore, different versions of string theory are related by different compactifications in a procedure known as T-duality.

The formulation of more precise versions of the meaning of compactification in this context has been promoted by discoveries such as the mysterious duality.

Flux compactification

[edit]A flux compactification is a particular way to deal with additional dimensions required by string theory.

It assumes that the shape of the internal manifold is a Calabi–Yau manifold or generalized Calabi–Yau manifold which is equipped with non-zero values of fluxes, i.e. differential forms, that generalize the concept of an electromagnetic field (see p-form electrodynamics).

The hypothetical concept of the anthropic landscape in string theory follows from a large number of possibilities in which the integers that characterize the fluxes can be chosen without violating rules of string theory. The flux compactifications can be described as F-theory vacua or type IIB string theory vacua with or without D-branes.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dean Rickles (2014). A Brief History of String Theory: From Dual Models to M-Theory. Springer, p. 89 n. 44.

Further reading

[edit]- Chapter 16 of Michael Green, John H. Schwarz and Edward Witten (1987). Superstring theory. Cambridge University Press. Vol. 2: Loop amplitudes, anomalies and phenomenology. ISBN 0-521-35753-5.

- Brian R. Greene, "String Theory on Calabi–Yau Manifolds". arXiv:hep-th/9702155.

- Mariana Graña, "Flux compactifications in string theory: A comprehensive review", Physics Reports 423, 91–158 (2006). arXiv:hep-th/0509003.

- Michael R. Douglas and Shamit Kachru "Flux compactification", Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 733 (2007). arXiv:hep-th/0610102.

- Ralph Blumenhagen, Boris Körs, Dieter Lüst, Stephan Stieberger, "Four-dimensional string compactifications with D-branes, orientifolds and fluxes", Physics Reports 445, 1–193 (2007). arXiv:hep-th/0610327.