Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

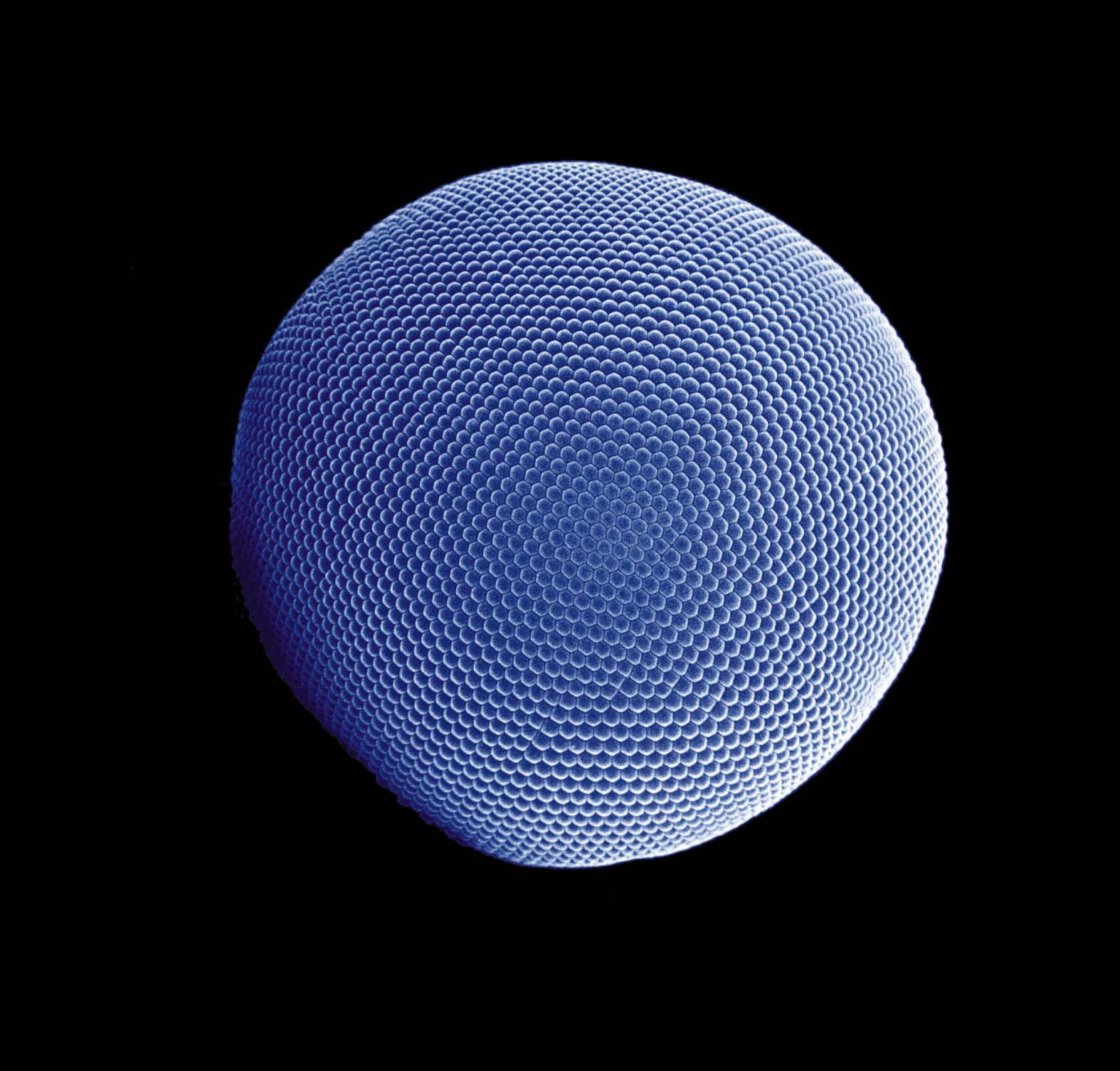

Compound eye

View on Wikipedia

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia,[1] which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which distinguish brightness and color. The image perceived by this arthropod eye is a combination of inputs from the numerous ommatidia, which are oriented to point in slightly different directions. Compared with single-aperture eyes, compound eyes have poor image resolution; however, they possess a very large view angle and the ability to detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light.[2] Because a compound eye is made up of a collection of ommatidia, each with its own lens, light will enter each ommatidium instead of using a single entrance point. The individual light receptors behind each lens are then turned on and off due to a series of changes in the light intensity during movement or when an object is moving, creating a flicker-effect known as the flicker frequency, which is the rate at which the ommatidia are turned on and off– this facilitates faster reaction to movement; honey bees respond in 0.01s compared with 0.05s for humans.[3]

Types

[edit]Compound eyes are typically classified as either apposition eyes, which form multiple inverted images, or superposition eyes, which form a single erect image.[4]

Apposition eyes

[edit]

Apposition eyes can be divided into two groups. The typical apposition eye has a lens focusing light from one direction on the rhabdom, while light from other directions is absorbed by the dark wall of the ommatidium. The mantis shrimp is the most advanced example of an animal with this type of eye. In the other kind of apposition eye, found in the Strepsiptera, each lens forms an image, and the images are combined in the brain.[5] This is called the schizochroal compound eye or the neural superposition eye (which, despite its name, is a form of the apposition eye).

Superposition eyes

[edit]The superposition eye is divided into three subtypes; the refracting, the reflecting, and the parabolic superposition eye. The refracting superposition eye has a gap between the lens and the rhabdom, and no side wall. Each lens takes light at an angle to its axis and reflects it to the same angle on the other side. The result is an image at half the radius of the eye, which is where the tips of the rhabdoms are. This kind is used mostly by nocturnal insects. In the parabolic superposition eye, seen in arthropods such as mayflies, the parabolic surfaces of the inside of each facet focus light from a reflector to a sensor array. Long-bodied decapod crustaceans such as shrimp, prawns, crayfish and lobsters are alone in having reflecting superposition eyes, which also have a transparent gap but use corner mirrors instead of lenses.

Other

[edit]

Good fliers like flies or honey bees, or prey-catching insects like praying mantises or dragonflies, have specialized zones of ommatidia organized into a fovea area which gives acute vision. In the acute zone the eye is flattened and the facets larger. The flattening allows more ommatidia to receive light from a spot and therefore higher resolution.

There are some exceptions from the types mentioned above. Some insects have a so-called single lens compound eye, a transitional type which is something between a superposition type of the multi-lens compound eye and the single lens eye found in animals with simple eyes. Then there is the mysid shrimp, Dioptromysis paucispinosa. The shrimp has an eye of the refracting superposition type, in the rear behind this in each eye there is a single large facet that is three times in diameter the others in the eye and behind this is an enlarged crystalline cone. This projects an upright image on a specialized retina. The resulting eye is a mixture of a simple eye within a compound eye.

Another version is the pseudofaceted eye, as seen in Scutigera. This type of eye consists of a cluster of numerous ocelli on each side of the head, organized in a way that resembles a true compound eye.

Asymmetries in compound eyes may be associated with asymmetries in behaviour. For example, Temnothorax albipennis ant scouts show behavioural lateralization when exploring unknown nest sites, showing a population-level bias to prefer left turns. One possible reason for this is that its environment is partly maze-like and consistently turning in one direction is a good way to search and exit mazes without getting lost.[6] This turning bias is correlated with slight asymmetries in the ants' compound eyes (differential ommatidia count).[7]

The body of Ophiomastix wendtii, a type of brittle star, was previously thought to be covered with ommatidia, turning its whole skin into a compound eye, but this has since been found to be erroneous; the system does not rely on lenses or image formation.[8]

Cultural references

[edit]"Dragonfly eyes" (Chinese: 蜻蜓眼 qingting yan) is a term for knobbly multi-coloured glass beads made in Western and Eastern Asia 2000–2500 years ago.[9] Owing to the multiple views and stimuli, compound eyes or dragonfly eyes have become a feature in art, film and literature, particularly in the 2010s. For example:

- The Man with the Compound Eyes, novel (2011) by Wu Ming-yi, English translation (2013) by Darryl Sterk

- Dragonfly Eyes, movie (2017) by Xu Bing

- Dragonfly Eyes, novel (2016) by Cao Wenxuan, English translation (2021) by Helen Wang

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Senses. Insect eyes". Insects and Spiders of the World. Volume 8: Scorpion fly - Stinkbug. New York: Marshall Cavendish. 2003. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-7614-7342-8.

- ^ Völkel, R.; Eisner, M.; Weible, K.J. (June 2003). "Miniaturized imaging systems" (PDF). Microelectronic Engineering. 67–68 (8): 461–472. doi:10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00102-3. Archived from the original on 2008-10-01.

- ^ Biologically Inspired Computer Vision: Fundamentals and Applications

- ^ Gaten, Edward (1998). "Optics and phylogeny: is there an insight? The evolution of superposition eyes in the Decapoda (Crustacea)". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (4): 223–236. doi:10.1163/18759866-06704001.

- ^ Buschbeck, Elke K. (1 July 2005). "The compound lens eye of Strepsiptera: morphological development of larvae and pupae". Arthropod Structure & Development. 34 (3): 315–326. Bibcode:2005ArtSD..34..315B. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2005.04.002. ISSN 1467-8039. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Hunt ER, et al. (2014). "Ants show a leftward turning bias when exploring unknown nest sites". Biology Letters. 10 (12) 20140945. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0945. PMC 4298197. PMID 25540159.

- ^ Hunt ER, et al. (11 April 2018). "Asymmetric ommatidia count and behavioural lateralization in the ant Temnothorax albipennis". Scientific Reports. 8 (1) 5825. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.5825H. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23652-4. PMC 5895843. PMID 29643429.

- ^ Sumner-Rooney L, Rahman IA, Sigwart JD, Ullrich-Lüter E (January 2018). "Whole-body photoreceptor networks are independent of 'lenses' in brittle stars". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 285 (1871) 20172590. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2590. PMC 5805950. PMID 29367398.

- ^ https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/microscopy-and-microanalysis/article/abs/nondestructive-analysis-of-dragonfly-eye-beads-from-the-warring-states-period-excavated-from-a-chu-tomb-at-the-shenmingpu-site-henan-province-china/E2FCF854D5324115F503E1643C33BDBD DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927612014201