Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Course (architecture)

View on Wikipedia

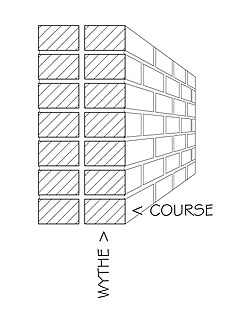

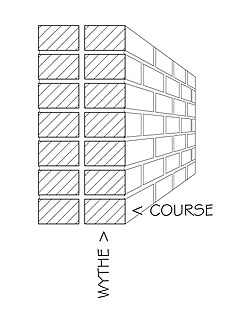

A course is a layer of the same unit running horizontally in a wall. It can also be defined as a continuous row of any masonry unit such as bricks, concrete masonry units (CMU), stone, shingles, tiles, etc.[1]

Coursed masonry construction arranges units in regular courses. In contrast, coursed rubble masonry construction uses random uncut units, infilled with mortar or smaller stones.[1]

If a course is the horizontal arrangement, then a wythe is a continuous vertical section of masonry[2] one unit in thickness. A wythe may be independent of, or interlocked with, the adjoining wythe(s). A single wythe of brick that is not structural in nature is referred to as a masonry veneer.

A standard 8-inch CMU block is exactly equal to three courses of brick.[3] A bond (or bonding) pattern) is the arrangement of several courses of brickwork.[2]

The corners of a masonry wall are built first, then the spaces between them are filled by the remaining courses.[4]

Orientations

[edit]

Masonry coursing can be arranged in various orientations, according to which side of the masonry unit is facing the outside and how it is positioned.[2]

Stretcher: Units are laid horizontally with their longest end parallel to the face of the wall.[1] This orientation can display the bedding of a masonry stone.

Header: Units are laid on their widest edge so that their shorter ends face the outside of the wall. They overlap four stretchers (two below and two above) and tie them together.[1]

Rowlock: Units laid on their narrowest edge so their shortest edge faces the outside of the wall.[1] These are used for garden walls and for sloping sills under windows, however these are not climate proof.[3] Rowlock arch has multiple concentric layers of voussoirs.[5]

Soldier: Units are laid vertically on their shortest ends so that their narrowest edge faces the outside of the wall.[1] These are used for window lintels or tops of walls.[3] The result is a row of bricks that looks similar to soldiers marching in formation, from a profile view.

Sailor: Units are laid vertically on their shortest ends with their widest edge facing the wall surface.[1] The result is a row of bricks that looks similar to sailors manning the rail.

Shiner or rowlock stretcher: Units are laid on the long narrow side with the broad face of the brick exposed.[6]

Types of courses

[edit]Different patterns can be used in different parts of a building, some decorative and some structural; this depends on the bond patterns.[2]

Stretcher course (Stretching course): This is a course made up of a row of stretchers.[1] This is the simplest arrangement of masonry units. If the wall is two wythes thick, one header is used to bind the two wythes together.[3]

Header course: This is a course made up of a row of headers.[1]

Bond course: This is a course of headers that bond the facing masonry to the backing masonry.[1]

Plinth: The bottom course of a wall.

String course (Belt course or Band course): A decorative horizontal row of masonry, narrower than the other courses, that extends across the façade of a structure or wraps around decorative elements like columns.[1][2][4]

Sill course: Stone masonry courses at the windowsill, projected out from the wall.[1]

Split course: Units are cut down so they are smaller than their normal thickness.[1]

Springing course: Stone masonry on which the first stones of an arch rest.[1]

Starting course: The first course of a unit, usually referring to shingles.[1]

Case course: Units form the foundation or footing course. It is the lowest course in a masonry wall used for multiple functions, mostly structural.[1]

Barge course: Units form the coping of a wall by bricks set on edge.[1]

See also

[edit]- Belt course

- Brickwork

- Plinth (architecture)

- Socle (architecture)

- Wythe

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Harris, Cyril (2006). Dictionary of Architecture and Construction (Forth ed.). United States of America: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071452373.

- ^ a b c d e Ballast, David; O'Hara, Steven (2016). ARE 5 Review Manual for the Architect Registration Exam. United States of America: Professional Publications Inc.

- ^ a b c d Allen, Edward; Iano, Joseph. Fundamentals of Building Construction (Sixth ed.). Wiley.

- ^ a b McKee, Harley (1973). Introduction to Early American Masonry. United States: National Trust for Historic Preservation.

- ^ "rowlock arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Sovinski, p. 43. "Those brick positions oriented in a horizontal alignment are called stretcher, header, rowlock stretcher, and rowlock. A rowlock stretcher is sometimes called a shiner."