Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ur[a] (/ʊr/ or /ɜːr/[3]) was a major Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar[b] (Arabic: تَلّ ٱلْمُقَيَّر, lit. 'mound of bitumen') in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. Although Ur was a coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, the coastline has shifted and the site is now well inland, on the south bank of the Euphrates, 16 km (10 mi) southwest of Nasiriyah in modern-day Iraq.[4] The city dates from the Ubaid period c. 3800 BC, and is recorded in written history as a city-state from the 26th century BC, its first recorded king being Mesannepada.

Key Information

The city's patron deity was the moon god Nanna (Sin in Akkadian), and the name of the city is derived from UNUGKI, literally "the abode (of Nanna)".[4] The site is marked by the partially restored ruins of the Ziggurat of Ur, which contained the shrine of Nanna, excavated in the 1930s. The temple was built in the 21st century BC (short chronology), during the reign of Ur-Nammu and was reconstructed in the 6th century BC by Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon.[5]

Society and culture

[edit]Archaeological discoveries have shown that Ur was a major Sumerian urban center on the Mesopotamian plain. The discovery of Ur's Royal Tombs further confirmed this. These tombs, which date to the Early Dynastic IIIa period (approximately in the 25th or 24th century BC), contained many luxury items made of precious metals and semi-precious stones imported from long distances (Ancient Iran, Afghanistan, India, Asia Minor, the Levant and the Persian Gulf).[5] This immense wealth shows Ur's economic importance during the Early Bronze Age.[6]

Excavation in the old city of Ur in 1929 revealed the Lyres of Ur, instruments similar to the modern harp but in the shape of a bull and with eleven strings.[7]

History

[edit]The site consists of a mound, roughly 1200 by 800 metres with a height of about 20 metres above the plain. The mound is split by the remnants of an ancient canal into north and south portions.[8] The remains of a city wall are visible surrounding the site. The occupation size ranged from about 15 hectares in the Jemdet Nasr period to 90 hectares in the Early Dynastic period and then peaking in the Ur III period at 108 hectares and the Isin-Larsa period at 140 hectares, extending beyond the city walls. Subsequent period had varying lesser degrees of occupation.[9]

Prehistory

[edit]When Ur was founded, the Persian Gulf's water level was two-and-a-half metres higher than today. Ur is thought, therefore, to have had marshy surroundings; irrigation would have been unnecessary, and the city's evident canals likely were used for transportation. Fish, birds, tubers, and reeds might have supported Ur economically without the need for an agricultural revolution sometimes hypothesized as a prerequisite to urbanization.[10]

Prehistoric Ubaid period

[edit]Archaeologists have discovered evidence of early occupation at Ur during the Ubaid period (c. 5500–3700 BC), a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia.[11] The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.[12]

Later, a layer of soil covered the occupation levels from the Ubaid period. Excavators of the 1920s interpreted the layer of soil as evidence for the Great Flood of the Epic of Gilgamesh and Book of Genesis. It is now understood that the South Mesopotamian plain was exposed to regular floods from the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, with heavy erosion from water and wind, which may have given rise to the Mesopotamian and derivative Biblical Great Flood stories.[13]

Early Bronze Age

[edit]There are various main sources informing scholars about the importance of Ur during the Early Bronze Age.

Early Dynastic period II

[edit]Proto-cuneiform tablets from the Early Dynastic period, c. 2900 BC, have been recovered.[14][15]

Early Dynastic period III

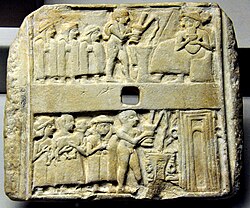

[edit]The First Dynasty of Ur seems to have had great wealth and power, as shown by the lavish remains of the Royal Cemetery at Ur. The Sumerian King List provides a tentative political history of ancient Sumer and mentions, among others, several rulers of Ur. Mesannepada is the first king mentioned in the Sumerian King List, and appears to have lived in the 26th century BC. That Ur was an important urban centre already then seems to be indicated by a type of cylinder seal called the City Seals. These seals contain a set of Proto-Cuneiform signs which appear to be writings or symbols of the name of city-states in ancient Mesopotamia. Many of these seals have been found in Ur, and the name of Ur is prominent on them.[16]

-

Empire of the Third Dynasty of Ur. West is at top, north at right.

-

Gold helmet of King of Ur I Meskalamdug, c. 2600–2500 BC

-

Mesopotamian female deity seated on a chair, Old-Babylonian fired clay plaque from Ur

-

Sumer and Elam c. 2350 BC. Ur was located close to the coastline near the mouth of the Euphrates.

Akkadian period

[edit]Ur came under the control of the Semitic-speaking Akkadian Empire (c. 2334–2154 BC) founded by Sargon the Great between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC. This was a period when the Semitic-speaking Akkadians, who had entered Mesopotamia in approximately 3000 BC, gained ascendancy over the Sumerians, and indeed much of the ancient Near East.

Ur III period

[edit]

After a short period of chaos following the fall of the Akkadian Empire the third Ur dynasty was established when the king Ur-Nammu came to power, ruling between c. 2047 BC and 2030 BC. During his rule, temples, including the Ziggurat of Ur, were built, and agriculture was improved through irrigation. His code of laws, the Code of Ur-Nammu (a fragment was identified in Istanbul in 1952) is one of the oldest such documents known, preceding the Code of Hammurabi by 300 years. He and his successor Shulgi were both deified during their reigns, and after his death he continued as a hero-figure: one of the surviving works of Sumerian literature describes the death of Ur-Nammu and his journey to the underworld.[17]

Ur-Nammu was succeeded by Shulgi, the greatest king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, who solidified the hegemony of Ur and reformed the empire into a highly centralized bureaucratic state. Shulgi ruled for a long time (at least 42 years) and deified himself halfway through his rule.[18]

The Ur empire continued through the reigns of three more kings with Akkadian names, Amar-Sin, Shu-Sin, and Ibbi-Sin. It fell around 1940 BC to the Elamites in the 24th regnal year of Ibbi-Sin, an event commemorated by the Lament for Ur.[19][20]

According to one estimate, Ur was the largest city in the world from c. 2030 to 1980 BC. Its population was approximately 65,000 (or 0.1 per cent share of global population then).[citation needed]

Middle Bronze Age

[edit]The site was occupied in the Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian periods. The city of Ur lost its political power after the demise of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Nevertheless, its important position which kept on providing access to the Persian Gulf ensured the ongoing economic importance of the city during the second millennium BC. The city came to be ruled by the Amorite first dynasty of Babylon which rose to prominence in southern Mesopotamia in the 19th century BC. During the Old Babylonian Empire, in the reign of Samsu-iluna, Ur was abandoned. It later became a part of the native Sealand Dynasty for several centuries.

Late Bronze Age

[edit]It then came under the control of the Kassites in the 16th century BC, and sporadically under the control of the Middle Assyrian Empire between the 14th and 11th centuries BC.[21]

Iron Age

[edit]The city, along with the rest of southern Mesopotamia and much of the Near East, Asia Minor, North Africa and southern Caucasus, fell to the north Mesopotamian Neo-Assyrian Empire from the 10th to late 7th centuries BC. From the end of the 7th century BC Ur was ruled by the so-called Chaldean Dynasty of Babylon. In the 6th century BC there was new construction in Ur under the rule of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. The last Babylonian king, Nabonidus, improved the ziggurat. However, the city started to decline from around 530 BC after Babylonia fell to the Persian Achaemenid Empire, and was no longer inhabited by the early 5th century BC. The demise of Ur was perhaps owing to drought, changing river patterns, and the silting of the outlet to the Persian Gulf.

Identification with the Biblical Ur

[edit]

Ur is possibly the city of Ur Kasdim mentioned in the Book of Genesis as the birthplace of the Jewish and Muslim patriarch Abraham (Avraham in Hebrew, Ibrahim in Arabic), traditionally believed to have lived some time in the 2nd millennium BC.[22] There are, however, conflicting traditions and scholarly opinions identifying Ur Kasdim with the sites of Şanlıurfa, Urkesh, Urartu, or Kutha.

The biblical Ur is mentioned four times in the Torah or Hebrew Bible (Tanakh in Hebrew), with the distinction "of the Kasdim"—traditionally rendered in English as "Ur of the Chaldees". The Chaldeans had settled in the vicinity by around 850 BC, but were not extant anywhere in Mesopotamia during the 2nd millennium BC period when Abraham is traditionally held to have lived. The Chaldean dynasty did not rule Babylonia (and thus become the rulers of Ur) until the late 7th century BC, and held power only until the mid 6th century BC. The name is found in Genesis 11:28, Genesis 11:31, and Genesis 15:7. In Nehemiah 9:7, a single passage mentioning Ur is a paraphrase of Genesis.[citation needed]

Pope John Paul II wanted to visit the city according to the biblical tradition as part of his trip to Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian territories but the visit was cancelled due to a dispute between the Government of Saddam Hussein and representatives of the Holy See.[23]

In March 2021, Pope Francis visited Ur during his journey through Iraq.[24]

Archaeology

[edit]

In 1625, the site was visited by Pietro Della Valle, who recorded the presence of ancient bricks stamped with strange symbols, cemented together with bitumen, as well as inscribed pieces of black marble that appeared to be seals. He retrieved several inscribed bricks.[25] It was visited in 1835 by James Baillie Fraser and John Ross who provided a detailed description.[26] In January 1850 William Loftus and H. A. Churchill visited the site and collected brick inscriptions.[27] European archaeologists did not identify Tell el-Muqayyar as the site of Ur until Henry Rawlinson successfully deciphered some bricks from that location, brought to England by William Loftus.[28]

The site was first excavated, on behalf of the British Museum and with instructions from the Foreign Office, by John George Taylor, British vice consul at Basra in 1853, 1854, and again in 1858.[29][30][31] It had long been thought that Taylor only worked at the site in 1853 and 1854 but a 48 page handwritten report of his work there in 1858 has now come to light. Finds from the dig included a carved stone with integral handle, a plaque with woman's face, and a foundation cone of A'annepada.[32] Taylor uncovered the Ziggurat of Ur and a structure with an arch later identified as part of the "Gate of Judgment".[33] Among the finds were copies of a standard cylinder of Nabonidus, Neo-Babylonian ruler, mentioning the prince regent Belshar-uzur, usually thought to be the Belshazzar of the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible.[34] Between 1854 and 1918 locals excavated over two hundred tablets from the site, mostly from the temple Ê-nun-maḫ, of the moon god Sin.[35] Built by the Ur III ruler Ur-Nammu, the ziggurat was later repaired by Isin ruler Ishme-Dagan early in the 2nd millennium BC.[36] Stamped bricks on the ziggurat detail the rebuilding of the temple of Ningal by 14th century BC Kassite ruler Kurigalzu I.[37]

Some cuneiform tablets were found. Thirty four of these tablets were inadvertently mixed in with those excavated at Kutalla. Only in recent years has this error been recognized.[38] Typical of the era, his excavations destroyed information and exposed the tell. Natives used the now loosened, 4,000-year-old bricks and tile for construction for the next 75 years, while the site lay unexplored, the British Museum having decided to prioritize archaeology in Assyria.[39]

The site was considered rich in remains, and relatively easy to explore. After some soundings were made during a week in 1918 by Reginald Campbell Thompson, H. R. Hall worked the site for one season (using 70 Turkish prisoners of war) for the British Museum in 1919, laying the groundwork for more extensive efforts to follow. Some cuneiform tablets from the Isin-Larsa period were found, including omen and medical texts. They are now in the British Museum.[40][41][42]

Excavations from 1922 to 1934 were funded by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania and led by the archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley.[43] The last two seasons focused on closing the site properly.[44][39][45] A total of about 1,850 burials were uncovered, including 16 that were described as "royal tombs" containing many valuable artifacts, including the Standard of Ur. Most of the royal tombs were dated to about 2600 BC. The finds included the unlooted tomb of a queen thought to be Queen Puabi (formerly transcribed as Shub-ab), known from a cylinder seal found in the tomb, although there were two other different and unnamed seals found in the tomb. Many other people had been buried with her, in a form of human sacrifice.[46] Near the ziggurat were uncovered the temple E-nun-mah and buildings E-dub-lal-mah (built for a king), E-gi-par (residence of the high priestess) and E-hur-sag (a temple building).

Outside the temple area, many houses used in everyday life were found. Excavations were also made below the royal tombs layer: a 3.5-metre-thick (11 ft) layer of alluvial clay covered the remains of earlier habitation, including pottery from the Ubaid period, the first stage of settlement in southern Mesopotamia. Woolley later wrote many articles and books about the discoveries.[47] One of Woolley's assistants on the site was the British archaeologist Max Mallowan.[48]

A number of royal inscriptions were found during the Woolley excavations.[49][50] Numerous cuneiform tablets were also recovered. These included archives, temple and domestic, from the Early Dynastic and Sargonic periods,[51][52][53][54] the Ur III period,[55][56] Old and Middle Babylonian period,[57][58] and the Neo-Babylonian and Persian periods.[59] Many literary and religious texts were also recovered.[60][61][62]

The discoveries at the site reached the headlines in mainstream media in the world with the discoveries of the Royal Tombs. As a result, the ruins of the ancient city attracted many visitors. One of these visitors was the already famous Agatha Christie, who as a result of this visit ended up marrying Max Mallowan.[63][64] During this time the site was accessible from the Baghdad–Basra railway, from a stop called "Ur Junction".[65]

In 2009, an agreement was reached for a joint University of Pennsylvania and Iraqi team to resume archaeological work at the site of Ur.[66] Excavations began in 2015 under the direction of Elizabeth C Stone and Paul Zimansky of the State University of New York. In part of the section they planned to work (designated AH) they found that a large area had been leveled to build a modern reconstruction of the fictional "House of Abraham" and another area have been paved over for a Papal visit.[67] The first excavation season was primarily to re-excavate Woolley's work in an Old Babylonian housing area with two new trenches for confirmation. Among the finds were a cylinder seal and balance pan weights. A number of cuneiform tablets were unearthed, a few Ur III period, a few from the Isin-Larsa period (including one from Rim-Sîn I year 24), a few Old Babylonian period, and a number of Old Akkadian period.[68] A similar though smaller dig was made in a Neo-Babylonian housing area. [69][70] In the 2017 season an urban area adjacent to Wooleys very large AH area was excavated. The burial vault of a Babylonian general Abisum was found. Abisum is known from year 36 of Hammurabi into the reign of Samsu-iluna. Thirty cuneiform tablets were found around the vault and another 12 inside the tomb itself. A 3rd excavation season was conducted in 2019 (the University of Pennsylvania excavated in 2023 though nothing has yet been published of that work).[71] A notable find was a large cuneiform tablet dated to the 6th year of Ur III ruler Ibbi-Sin on the swap of two large residences between private individuals (Munimah and Gayagama). One home was about 240 square meters and the other 423 square meters which is especially large for a home in that time.[72]

Some distance south of Area AH in 2017 and 2019 a German team of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München directed by Adelheid Otto excavated a large home of Sîn-nādā (mid 19th century BC) chief administrator of the Temple of Ningal in the Isin-Larsa period. In levels below the final occupation were found tablets dating to Sin-Eribam and Silli-Adad, rulers of Larsa. They included a new copy of the Lament for Sumer and Ur.[73][74][75]

The Royal Tomb Excavation

[edit]

When the Royal Tombs at Ur were discovered, their size was unknown. Excavators started digging two trenches in the middle of the desert to see if they could find anything that would allow them to keep digging. They split into two teams – A and team B. Both teams spent the first few months digging a trench and found evidence of burial grounds by collecting small pieces of golden jewelry and pottery. This was called the "gold trench". After the first season of digging finished, Woolley returned to England. In Autumn, Woolley returned and started the second season. By the end of the second season, he had uncovered a courtyard surrounded by many rooms.[77] In their third season of digging archaeologists had uncovered their biggest find yet, a building that was believed to have been constructed by order of the king, and a second building thought to be where the high priestess lived. As the fourth and fifth season came to a close, they had discovered so many items that most of their time was now spent recording the objects they found instead of actually digging objects.[78] Items included gold jewelry, clay pots and stones. One of the most significant objects was the Standard of Ur. By the end of their sixth season they had excavated 1850 burial sites and deemed 17 of them to be "Royal Tombs". Some clay sealings and cuneiform tablet fragment were found in an underlying layer.[79]

Woolley finished his work excavating the Royal Tombs in 1934, uncovering a series of burials. Many servants were killed and buried with the royals, who he believed went to their deaths willingly. Computerized tomography scans on some of the surviving skulls have shown signs that they were killed by blows to the head that could be from the spiked end of a copper axe, which showed Woolley's initial theory of mass suicide via poison to be incorrect.[80]

Inside Puabi's tomb there was a chest in the middle of the room. Underneath that chest was a hole in the ground that led to what was called the "King's Grave": PG-789. It was believed to be the king's grave because it was buried next to the queen. In this grave, there were 63 attendants who were all equipped with copper helmets and swords. It is thought to be his army buried with him. Another large room was uncovered, PG-1237, called the "Great death pit". This large room had 74 bodies, 68 of which were women. This was based on artifacts found with the bodies, weapons and whetstones in the case of males and simple, non-gold, jewelry in the case of females. There is some debate about the gender of one body. Two large ram statues were found in PG-1237 which are believed to be the remains of lyres. Several lyres were found just outside the entrance. The bodies were found to have perimortem blunt force injuries which caused their death. They also had skeleton markers for long term manual labor.[81][82][83]

Most of the treasures excavated at Ur are in the British Museum, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the Baghdad Museum. At the Penn Museum the exhibition "Iraq's Ancient Past",[84] which includes many of the most famous pieces from the Royal Tombs, opened to visitors in late Spring 2011. Previously, the Penn Museum had sent many of its best pieces from Ur on tour in an exhibition called "Treasures From the Royal Tombs of Ur." It traveled to eight American museums, including those in Cleveland, Washington and Dallas, ending the tour at the Detroit Institute of Art in May 2011.[citation needed]

Samples from two stratigraphic layers in the royal cemetery area, from before the royal burials, have been radiocarbon dated. The ED Ia layer dated to c. 2900 BC and the ED Ic layer to c. 2679 BC.[85][86]

Current status and preservation

[edit]Though some of the areas that were cleared during modern excavations have sanded over again, the Great Ziggurat is fully cleared and stands as the best-preserved and most visible landmark at the site.[87] The famous Royal tombs, also called the Neo-Sumerian Mausolea, located about 250 metres (820 ft) south-east of the Great Ziggurat in the corner of the wall that surrounds the city, are nearly totally cleared. Parts of the tomb area appear to be in need of structural consolidation or stabilization.[citation needed]

There are cuneiform (Sumerian writing) on many walls, some entirely covered in script stamped into the mud-bricks. The text is sometimes difficult to read, but it covers most surfaces. Modern graffiti has also found its way to the graves, usually in the form of names made with coloured pens (sometimes they are carved).[citation needed]

The Great Ziggurat itself has far more graffiti, mostly lightly carved into the bricks. The graves are completely empty. A small number of the tombs are accessible. Most of them have been cordoned off. The whole site is covered with pottery debris, to the extent that it is virtually impossible to set foot anywhere without stepping on some. Some have colours and paintings on them. Some of the "mountains" of broken pottery are debris that has been removed from excavations.

Pottery debris and human remains form many of the walls of the royal tombs area. In May 2009, the United States Army returned the Ur site to the Iraqi authorities, who hope to develop it as a tourist destination.[88]

Since 2009, the non-profit organization Global Heritage Fund (GHF) has been working to protect and preserve Ur against the problems of erosion, neglect, inappropriate restoration, war and conflict. GHF's stated goal for the project is to create an informed and scientifically grounded Master Plan to guide the long-term conservation and management of the site, and to serve as a model for the stewardship of other sites.[89]

Since 2013, the institution for Development Cooperation of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs DGCS[90] and the SBAH, the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of the Iraqi Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, have started a cooperation project for "The Conservation and Maintenance of Archaeological site of UR". In the framework of this cooperation agreement, the executive plan, with detailed drawings, is in progress for the maintenance of the Dublamah Temple (design concluded, works starting), the Royal Tombs—Mausolea 3rd Dynasty (in progress)—and the Ziqqurat (in progress). The first updated survey in 2013 has produced a new aerial map derived by the flight of a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) operated in March 2014. This is the first high-resolution map, derived from more than 100 aerial photograms, with an accuracy of 20 cm or less. A preview of the ortho-photomap of Archaeological Site of Ur is available online.[91]

Tell Sakhariya

[edit]The site (30º 58’ 33.84” N by 46º 08’ 28.36” E) was first noted, as Tell Abu Ba’arura Shimal ("Father of Sheep Droppings, North"), as a Kassite period occupation (300 NE X 150 X 2.5. Cassite: 3.5 ha) during an archaeological survey of the region in the 1960s.[92] The site, which lies 6.45 kilometers northeast of Ur, was excavated in a five week season from December to January 2011 – 2012 by a joint Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage and the State University of New York at Stony Brook team led by Elizabeth Stone and Paul Zimansky. It was measured at about 250 meters by 200 meters with two high points, about 3.5 meters above the plain, separated by a saddle. Seven trenches were dug, some small, and three yielded simple slope wash.[93] On the surface were found Kassite and Old Babylonian period ceramics and satellite imagery suggested the presence of a large square building and a number of other walls but the excavators found no building remains in surface or magnetic gradiometry surveys, or in the later trenches. Three occupational levels were determined. The top layer contained Kassite pottery fragments, a late Kassite kiln, and a number of late Kassite burials. The second held Sealand Dynasty ceramics along with lithic (grinding stones, cuboids and one balance weight), metal, floral and faunal (primarily cattle, sheep, and goats) remains.[94] The excavators deemed the occupations to be repeated but transient. Neither level showed signs of formal or residential architecture.

The final, earliest level also lacked notable architecture but featured a very large mud or clay platform, made from clean material, devoid of sherds, bones, or other living debris. Coring to a depth of 4 meters (1 meter below the plain) failed to find the bottom of the platform. Part of the platform is underlain by a square baked brick pavement and remains of a fish pond were found. Two 5 meter by 10 meter trenches, 55 meters apart, were excavated in this platform. An inscribed brick of the first Ur III ruler Ur-Nammu (c. 2112-2094 BC) "describing the construction of a barag - a pedestal or podium and a garden" was found out of context. Also found were four fragmentary inscribed bricks (surface finds), three inscribed cones (one datable to Larsa ruler Rim-Sîn I (c. 1822-1763 BC) year 15), and two Sumerian language cuneiform tablets. One tablet was from the early Kassite period and the other tablet was a receipt for copper utensils is dated to year 28 of Ur III ruler Shulgi (c. 2094-2046 BC). After this excavation season a nearby prison was expanded by the Iraqi government blocking access to the site and precluding further campaigns.[95] It has been proposed as the site of Ur III Ga’eš. The ziggurat at Ur can be seen from the summit of the site.[96][97][98][99]

Ga’eš

[edit]Based on the archaeology the site of Tell Sakhariya has been proposed as the Ur III period city of Ga’eš (ga-eški and ga-eš5ki), site of the Akiti festival of Nanna/Sin, held every year for 11 days in the seventh month of the year and 7 days in the first month of the year. The festival began at Nanna’s temple in Ur and ended in Ga’eš, possibly traveling via a canal.[100] The temple of Nanna/Sin there was called the Karzida (kar-zi-da) was located at Ga’eš (the names Karzida and Ga’eš appear to have been used interchangeably for the city). The 36th year name of Ur III ruler Shulgi read "Year Nanna of Ga’eš was brought into his temple" and the 9th year name of Ur III ruler Amar-Sin read "Year En-Nanna-Amar-Sin-kiagra, was installed for the third time as en-priestess of Nanna of Ga’eš / of Karzida". Amar-Sin established a Giparu (nunnery) for the en-priestess of Nanna at Karzida saying "he caused En-aga-zi-ana, his beloved priestess (en), to enter there".[101] When the en-priestess died she was buried a with "golden crown (aga), which is followed by five other golden objects".[102][103][104] From tablets found at Ur it is known that wrestling competitions were held at Ga’eš reading "for the ‘house of wrestling’ in the Akiti (building), issued in Ga’eš, during the Akiti month" and "100 liters of ordinary beer, the beer for the ‘house of wrestling’ … issued in Ga’eš", for example.[105] All that is known with certainty about its location is that it lay one days journey from Ur and was on a canal. A sketch in a 1990's paper concerning the Iturungal Canal placed Ga’eš in a location corresponding to Tell Sakhariya.[106] It has been suggested that Ga’eš was mentioned in Early Dynastic II period administrative texts.[107] The final textual mention of was from the time of Larsa ruler Sin-Iddinam (c. 1849-1843 BC) a cone reading "Sm-i[ddinam], mighty man, [s]on [born] in Ga’eš provider of U[r], king of Lars[a], king of the land of S[umer] and Akkad] ...".[108] Apparently Ga’eš had a gate tower based on a text from Drehem "1 fattened sheep for the great gate tower in Ga’eš" dating to the reign of Su-Sin.[109]

One of the Temple Hymns of Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2334-2279 BC), is dedicated to Ga’eš and the Karzida temple of Nanna/Sin there.[110]

"Shrine, great sanctuary?, founded at a cattle-pen, ‘Small’ city, . . . . of Suen Karzida, your interior is a . . . . place, your foundation is holy and clean, Shrine, your Gipar is founded in purity, Your door is (of) strong copper, set up at a great place, Cattle-pen (filled with) the lowing (of the cows), like a young bull you . . . the horn,Your prince, the lord of heaven, standing in the . . . ., At noon (like the sun) radiating . . . ., O Karzida, he, Ašimbabbar, has placed the house upon your . . . . has taken his place on your dais. The house of Nanna in Ga’eš"[95]

Ga’eš was also mentioned in the Sumerian literary composition Lament for Sumer and Ur

"... Mighty strength was set against the banks of the Id-nuna-Nanna canal. The settlements of the E-danna of Nanna, like substantial cattle-pens, were destroyed. Their refugees, like stampeding goats, were chased (?) by dogs. They destroyed Gaeš like milk poured out to dogs, and shattered its finely fashioned statues. 'Alas, the destroyed city, my destroyed house,' Its sacred Ĝipar of en priesthood was defiled. Its en priestess was snatched from the Ĝipar and carried off to enemy territory. A lament was raised at the dais that stretches out toward heaven. Its heavenly throne was not set up, was not fit to be crowned (?)."[111][112]

And in another composition:

"O, sanctuary, big chamber built like ? a stall, mighty beaming city of Suen, Karzida, your interior is a powerful place, your foundation is holy and clean. O, sanctuary, your Ĝipar is established in purity, your door is copper, something (very) strong, established in the Underworld. O, cattle-pen, which rai[ses] the horns like a breeding bull, your prince, the lord of heaven standing in ... joy. ... at midday and ... O Karzida, Ašimbabbar, a house has established in your holy space and took (his) residence in your sanctuary!"[113]

List of rulers

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2024) |

The Sumerian King List (SKL) gives a list of only thirteen rulers from three dynasties of Ur. The once supposed second dynasty of Ur may have never existed.[114] The first dynasty of Ur may have been preceded by one other dynasty of Ur (the "Kalam dynasty") unnamed on the SKL—which had extensive influence over the area of Sumer and apparently led a union of south Mesopotamian polities. This predynastic period of Ur may include at least two rulers out of the first eight on this list (Meskalamdug and Akalamdug). The following list should not be considered complete:

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Titles | Approx. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic IIIa period (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

| Predynastic Ur (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

|

A-Imdugud 𒀀𒀭𒅎𒂂 |

Governor of Ur | c. 2600 BC |

| ||

|

Ur-Pabilsag 𒌨𒀭𒉺𒉋𒊕 |

Possibly son of A-Imdugud[116] | King of Ur | c. 2550 BC | ||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Titles | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BC) | ||||||

| Kalam dynasty (c. 2550 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

|

Akalamdug 𒀀𒌦𒄭 |

Possibly son of Meskalamdug | King of Ur | c. 2550 BC | ||

|

Meskalamdug 𒈩𒌦𒄭 |

Possibly son of Akalamdug | King of Kish | c. 2550 BC | ||

|

Puabi 𒅤𒀜 |

Possibly Coregent with Meskalamdug | Queen of Ur | c. 2550 BC |

| |

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Titles | Approx. dates | Notes |

| First dynasty of Ur / Ur I dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2340 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1 |

|

Mesannepada 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 |

Son of Meskalamdug | King of Sumer King of Kish King of Ur |

c. 2550 - c. 2525 BC |

|

| 2 |

|

Meskiagnun 𒈩𒆠𒉘𒉣 |

Son of Mesannepada | King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2485 - c. 2450 BC |

|

| 3 |

|

Elulu 𒂊𒇻𒇻 |

King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2445 BC | ||

| 4 |

|

Balulu 𒁀𒇻𒇻 |

King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2445 BC |

| |

— SKL | ||||||

|

Lugal-kinishe-dudu 𒈗𒆠𒉌𒂠𒌌𒌌 |

King of Sumer King of Uruk and Ur[117] King of Kish King of Uruk Governor of Uruk Lord of Uruk |

c. 2400 BC |

| ||

|

Lugal-kisal-si 𒈗𒆦𒋛 |

Son of Lugal-kinishe-dudu[117] | King of Uruk and Ur[117] King of Kish King of Uruk King of Ur |

c. 2400 BC | ||

|

Enshakushanna 𒂗𒊮𒊨𒀭𒈾 |

Lord of Sumer and King of all the Land King of Sumer King of Uruk King of Ur |

c. 2350 BC | |||

| Proto-Imperial period (c. 2350 – c. 2334 BC) | ||||||

| A'annepada 𒀀𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 |

Son of Mesannepada | King of Ur | c. 2350 BC | |||

| Lunanna 𒇽𒀭𒋀𒆠 |

King of Ur | Uncertain; this ruler may have r. c. 2350 – c. 2112 BC sometime during the Proto-Imperial period.[117] | ||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Titles | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Akkadian period (c. 2334 – c. 2154 BC) | ||||||

| Second dynasty of Ur / Ur II dynasty (c. 2340 – c. 2112 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1 |

|

Nanni 𒈾𒀭𒉌 |

King of Sumer King of Ur |

r. c. 2340 BC (54 or 120 years) |

| |

| 2 | Meskiagnun II 𒈩𒆠𒉘𒉣 |

Son of Nanni | King of Sumer King of Ur |

Uncertain (48 years) |

| |

| 3 | Unknown | King of Sumer King of Ur |

Uncertain (2 years) |

| ||

— SKL | ||||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Titles | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Ur III period (c. 2154 – c. 2004 BC) | ||||||

| Third dynasty of Ur / Ur III dynasty (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1 |

|

Ur-Nammu 𒌨𒀭𒇉 |

Possibly son of Utu-hengal | King of Sumer and Akkad King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2112 – c. 2094 BC | |

| 2 |

|

Shulgi 𒀭𒂄𒄀 |

Son of Ur-Nammu and Watartum | King of the Four Corners King of Sumer and Akkad King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC | |

| 3 |

|

Amar-Sin 𒀭𒀫𒀭𒂗𒍪 |

Possibly son of Shulgi | King of the Four Corners King of Sumer and Akkad King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2046 – c. 2037 BC | |

| 4 |

|

Shu-Sin 𒀭𒋗𒀭𒂗𒍪 |

Possibly son of Amar-Sin | King of the Four Corners King of Sumer and Akkad King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2037 – c. 2028 BC | |

| 5 |

|

Ibbi-Sin 𒀭𒄿𒉈𒀭𒂗𒍪 |

Son of Shu-Sin | King of the Four Corners King of Sumer and Akkad King of Sumer King of Ur |

c. 2028 – c. 2004 BC | |

— SKL | ||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Literal transliteration: Urim2 = ŠEŠ. ABgunu = ŠEŠ.UNUG (𒋀𒀕) and Urim5 = ŠEŠ.AB (𒋀𒀊), where ŠEŠ=URI3 (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.)

References

[edit]- ^ Kramer, S. N. (1963). The Sumerians, Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28, 298.

- ^ Edwards, I. E. S.; et al. (December 2, 1970). The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. Part 1, p. 149. ISBN 9780521070515.

- ^ Agnes, Michael, ed. (2001). Webster's New World College Dictionary (4th ed.).

- ^ a b Ebeling, Erich; Meissner, Bruno; Edzard, Dietz Otto (1997). Meek – Mythologie. Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German). De Gruyter. p. 360. ISBN 978-3-11-014809-1.

- ^ a b R. L. Zettler, L. Horne, "Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur", University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1998 ISBN 978-0924171550

- ^ Aruz, J., ed. (2003), Art of the First Cities. The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, New York, the U.S.A.: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Galpin, F. W. (1929). "The Sumerian Harp of Ur, c. 3500 B. C.". Music & Letters. 10 (2). Oxford University Press: 108–123. doi:10.1093/ml/X.2.108. ISSN 0027-4224. JSTOR 726035.

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild, "The Waters of Ur", Iraq, vol. 22, pp. 174–85, 1960

- ^ [1] Hammer, Emily, and Angelo Di Michele, "The Suburbs of the Early Mesopotamian City of Ur (Tell al-Muqayyar, Iraq)", American Journal of Archaeology 127.4, pp. 449-479, 2023

- ^ Jennifer R. Pournelle, "KLM to CORONA: A Bird's Eye View of Cultural Ecology and Early Mesopotamian Urbanization"; in Settlement and Society: Essays Dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams ed. Elizabeth C. Stone; Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, and Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2007.

- ^ [2] Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham, "Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East", Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 63, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2010 ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0

- ^ [3]Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard, "Al-Ubaid: a report on the work carried out at Al-Ubaid for the British museum in 1919 and for the Joint expedition in 1922-3", Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927

- ^ "Secrets of Noah's Ark – Transcript". Nova. PBS. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ Lecompte, Camille. "Observations on Diplomatics, Tablet Layout and Cultural Evolution of the Early Third Millennium: The Archaic Texts from Ur". Materiality of Writing in Early Mesopotamia, edited by Thomas E. Balke and Christina Tsouparopoulou, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 133-164, 2016

- ^ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, "An Archaic Recording System and the Origin of Writing." Syro Mesopotamian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 1977

- ^ Matthews, R.J., "Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur", Berlin, 1993

- ^ Amélie Kuhrt (1995). The Ancient Near East: C.3000-330 B.C. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16762-0.

- ^ Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-521-56496-4. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Ur III Period (2112–2004 BC) by Douglas Frayne, University of Toronto Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8020-4198-1

- ^ Dahl, Jacob Lebovitch (2003). The ruling family of Ur III Umma. A Prosopographical Analysis of an Elite Family in Southern Iraq 4000 Years ago (PDF). UCLA dissertation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-12.

- ^ Brinkman, J. A., "Review of 'Ur: The Kassite Period and the Period of the Assyrian Kings'", Orientalia, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 310–48, 1969

- ^ "Journey of Faith". National Geographic Magazine. May 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ Pullella, Philip (2020-12-07). "Pope Francis to make risky trip to Iraq in early March". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ Lowen, Mark (2021-03-05). "Pope Francis on Iraq visit calls for end to violence and extremism". BBC News. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ P. Delia Valle, "Les fameux voyages de Pietro Delia Valle, gentil-homme Romain, surnomm? l'illustre voyageur", Vol. 4, Paris, 1663-1665

- ^ [4]Fraser, James Baillie, "Travels in Koordistan, Mesopotamia, Etc: Including an Account of Parts of Those Countries Hitherto Unvisited by Europeans", R. Bentley, 1840

- ^ Curtis, J. E., "William Kennett Loftus: A 19th-Century Archaeologist in Mesopotamia. Letters Transcribed and Introduced by John Curtis", London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2023

- ^ [5]William Loftus, "Travels and researches in Chaldæa and Susiana; with an account of excavations at Warka, the Erech of Nimrod, and Shúsh, Shushan the Palace of Esther, in 1849-52", J. Nisbet and Co, 1857

- ^ [6] J.E. Taylor, "Notes on the Ruins of Muqeyer", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 15, pp. 260–276, 1855.

- ^ [7] JE Taylor, "Notes on Abu Shahrein and Tel-el-Lahm", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 15, pp. 404–415, 1855

- ^ E. Sollberger, "Mr. Taylor in Chaldaea", Anatolian Studies, vol. 22, pp. 129–139, 1972.

- ^ Curtis, John, "Two Babylonian beakers and an unpublished report on excavations at Ur in 1858", TRACING TRANSITIONS & CONNECTING COMMUNITIES, pp. 119-134, 2025

- ^ Crawford 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Langdon, S., "New Inscriptions of Nabuna’id", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 102–17, 1916

- ^ Grice, E. M., "Records from Ur and Larsa Dated in the Larsa Dynasty", YOS 5, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1919

- ^ Clayden, Tim, "Ur in the Kassite Period", Babylonia under the Sealand and Kassite Dynasties, edited by Susanne Paulus and Tim Clayden, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 88-124, 2020

- ^ T. Clayden, "The Date of the Foundation Deposit in the Temple of Ningal at Ur", Iraq, vol. 57, pp. 61–70, 1995

- ^ Charpin, Dominique, "Archives familiales et propriéte privée en Babylonie ancienne: étude des documents de" Tell Sifr", Vol. 12, Librairie Droz, 1980

- ^ a b Leonard Woolley, "Excavations at Ur: A Record of Twelve Years' Work", Apollo, 1965 ISBN 0-8152-0110-9.

- ^ H. R. Hall, "The Excavations of 1919 at Ur, el-'Obeid, and Eridu, and the History of Early Babylonia", Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 25, pp. 1–7, 1925.

- ^ H. R. Hall, "Ur and Eridu: The British Museum Excavations of 1919", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 9, no. 3/4, pp. 177–195, 1923.

- ^ Hall, H. R., "A Season’s Work at Ur, Al-‘Ubaid, Abu Sharain (Eridu), and Elsewhere Being an Unofficial Account of the British Museum Archaeological Mission to Babylonia, 1919", London: Methuen Co. Ltd., 1930

- ^ Woolley, C. L., "Excavations at Ur of the Chaldees", Antiquaries Journal, 3, pp. 312–333 and pl. XXIV, 1923

- ^ Leonard Woolley, Ur: The First Phases, Penguin, 1946.

- ^ Leonard Woolley and P. R. S. Moorey, "Ur of the Chaldees: A Revised and Updated Edition of Sir Leonard Woolley's Excavations at Ur", Cornell University Press, 1982 ISBN 0-8014-1518-7.

- ^ [8]Zimmerman, Paul C., and Richard L. Zettler, "Two Tombs or Three? PG 789 and PG 800 Again!.", From Sherds to Landscapes: Studies on the Ancient Near East in Honor of McGuire Gibson 71, Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 283–296, 2021 ISBN 978-1-61491-063-3

- ^ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ^ Mallowan, M. E. L., "Memories of Ur", Iraq 22, pp. 1–19, 1960

- ^ [9] C. J. Gadd & L. Legrain, with contributions by Sidney Smith and E. R. Burrows, "Royal Inscriptions", UET 1, London, 1928

- ^ E. Sollberger, "Royal Inscriptions Part II", UET 8, London, 1965

- ^ [10] E. Burrows, "Archaic Texts", UET 2, London, 1935

- ^ Alberti, A./F. Pomponio, "Pre-Sargonic and Sargonic Texts from Ur Edited in UET 2, Supplement", Studia Pohl Series Minor 13, Rome, 1986

- ^ Visicato, G./A. Westenholz, "An Early Dynastic Archive from Ur Involving the Lugal", Kaskal 2, pp. 55–7, 2005

- ^ Saadoon, Abather and Kraus, Nicholas, "The Lost Months of Ur: New Early Dynastic and Sargonic Tablets from the British Museum", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 1-11, 2024

- ^ L. Legrain, "Business Documents of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Plates", UET 3, London, 1937

- ^ [11] D. Loding, "Economic Texts from the Third Dynasty", UET 9, Philadelphia, 1976

- ^ H. H. Figulla & W. J. Martin, "Letters and Documents of the Old-Babylonian Period", UET 5, London, 1953

- ^ O. R. Gurney, "Middle Babylonian Legal Documents and Other Texts", UET 7, London, 1974

- ^ H. Figulla, "Business Documents of the New Babylonian Period", UET 4, London, 1949

- ^ C. J. Gadd & S. N. Kramer, "Literary and Religious Texts. First Part", UET 6/1, London, 1963

- ^ C. J. Gadd & S. N. Kramer, "Literary and Religious Texts. Second Part", UET 6/2, London, 1966

- ^ A. Shaffer, "Literary and Religious Texts. Third Part", UET 6/3, London, 2006

- ^ Brunsdale, Mitzi M. (26 July 2010). Icons of Mystery and Crime Detection: From Sleuths to Superheroes [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-313-34531-9.

- ^ "The World This Weekend - Sir Max Mallowan". BBC Archive. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Crawford 2015. p. 5. "It used to be close to the Basra to Baghdad railway, part of the proposed Berlin to Basra line that was never completed. It was possible to get off the train from Baghdad at the grandly named Ur Junction, where a branch line turned off to Nasariyah, and drive a mere two miles across the desert to the site itself, but the station was closed sometime after the Second World War, leaving a long, hot journey in a four-wheeled vehicle as the only option."

- ^ [12] U.S. Archaeologists To Excavate In Iraq - Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

- ^ Hammer, Emily, "The City and Landscape of UR: An Aerial, Satellite, and Ground Reassessment", Iraq. Journal of the British Institute for the Study of Iraq, vol. 81, pp. 173–206, 2019

- ^ Charpin, Dominique, "Epigraphy of Ur: Past, Present, and Future", Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016, edited by Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 181-194, 2021

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth C; Zimansky, Paul, Archaeology Returns to Ur: A New Dialog with Old Houses, Near Eastern Archaeology; Chicago, vol. 79, iss. 4, pp. 246–259 Dec 2016

- ^ Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman ed., "Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE", "Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016", Penn State University Press, 2021 ISBN 9781646021512

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth, and Paul Zimansky, "“Alas the destroyed city!” A search for private houses of the Ur III period at Ur", TRACING TRANSITIONS & CONNECTING COMMUNITIES, pp. 301-313, 2025

- ^ Charpin, D., "L’habitat à Ur, capitale de la IIIe dynastie. Le témoignage d’un document de 2021 av. J.-C. découvert en février 2019", in Béranger, M., Nebiolo, F. and Ziegler, N. eds. Dieux, rois et capitales dans le Proche-Orient ancien. Compte Rendu de la LXVe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. (Paris, 8-12 juillet 2019). PIPOAC 5, Louvain/Paris/Bristol: Peeters, pp. 27-60, 2023

- ^ [13] Charpin, Dominique, "Priests of Ur in the Old Babylonian Period: a Reappraisal in Light of the 2017 Discoveries at Ur/Tell Muqayyar", Journal of ancient near eastern religions 19.1-2, pp. 18-34, 2019

- ^ D. Charpin, "Les tablettes retrouvées dans les tombes de maisons à Ur à l'époque paléo-babylonienne", in: D. Charpin (ed.), Archibab 4. Nouvelles recherches sur la ville d'Ur à l'époque paléo-babylonienne, Mémoires de NABU 22, Paris, 2019

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth, et al., "Two Great Households of Old Babylonian Ur", Near Eastern Archaeology 84.3, pp. 182-191, 2021

- ^ Taylor, Jonathan, "Sîn-City: New Light from Old Excavations at Ur", Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016, edited by Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 35-48, 2021

- ^ "The Royal Tombs of Ur – Story". Mesopotamia.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ Hauptmann, Andreas, Klein, Sabine, Paoletti, Paola, Zettler, Richard L. and Jansen, Moritz. "Types of Gold, Types of Silver: The Composition of Precious Metal Artifacts Found in the Royal Tombs of Ur, Mesopotamia" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 108, no. 1, 2018, pp. 100–131

- ^ Benati, Giacomo and Lecompte, Camille. "From Field Cards to Cuneiform Archives: Two Inscribed Artifacts from Archaic Ur and Their Archaeological Context" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 106, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1–15

- ^ McCorriston Joy, Field Julie (2019). World Prehistory and the Anthropocene An Introduction to Human History. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-500-843185.

- ^ Vidale, Massimo, "PG 1237, Royal Cemetery of Ur: Patterns in Death", Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21.3, pp. 427-451, 2011

- ^ Molleson, Theya, and Dawn Hodgson, "The Human Remains from Woolley's Excavations at Ur", Iraq, vol. 65, pp. 91-129, 2003

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni, "Who was Buried in the Royal Tombs of Ur? the Epigraphic and Textual Data", Orientalia (Roma), vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 153-197, 2004

- ^ "Iraq's Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur's Royal Cemetery". Penn.museum. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Camille Lecompte, and Giacomo Benati, "Nonadministrative Documents from Archaic Ur and from Early Dynastic I–II Mesopotamia: A New Textual and Archaeological Analysis", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 69, pp. 3–31, 2017

- ^ Wencel, M. M., "Radiocarbon Dating of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia: Results, Limitations, and Prospects", Radiocarbon 59, pp. 635–45, 2017

- ^ "Soldiers visit historical ruins of Ur", Nov 18, 2009, by 13th Sustainment Command Expeditionary Public Affairs, web: Army-595.

- ^ [14] US returns Ur, birthplace of Abraham, to Iraq AFP 2009-05-14

- ^ Ur preservation project at the Global Heritage Fund

- ^ Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs DGCS Ur funding

- ^ "UAV aerial Ur Photograph". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ^ [15] Wright, H.T., "The southern margins of Sumer: archaeological survey of the area of Eridu and Ur", in R.M. Adams (ed.) Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 323–45, 1981

- ^ SBU Faculty Conduct Archaeological Excavations in Iraq - Stony Brook University - March 12, 2012

- ^ Wolfhagen, Jesse, and Max D. Price, "A probabilistic model for distinguishing between sheep and goat postcranial remains", Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 12, pp. 625-631, 2017

- ^ a b Zimansky, Paul, "Was the Karzida of Ur’s Akītu Festival at Tell Sakhariya?", Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016, edited by Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 525-532, 2021

- ^ Twiss, Katheryn C., "Animals of the Sealands: Ceremonial Activities in the Southern Mesopotamian “Dark Age”", Iraq 79, pp. 257-267, 2017

- ^ Zimansky, Paul, et al., "Tell Sakhariya and Gaeš", Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 3, pp. 57-66, 2016

- ^ Al-Hamdani, A., "Excavation at Tell Sakhariya in Dhiqar Province in Southern Iraq", Taarii Newsletter 7.1, pp. 17-19, 2012

- ^ Zimansky, Paul, and Elizabeth C. Stone, "Excavations at Tell Sakhariya: A Sealand Site near Ur", 58e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, July 2012

- ^ Falkenstein, A., "akiti-Fest und akiti-Festhaus", R. von Kienle et a!. (eds.), Festschrift Johannes Friedrich. Heidelberg, pp. 147-182, 1959

- ^ Nett, Seraina, "The Office and Responsibilities of the En Priestess of Nanna: Evidence from Votive Inscriptions and Documentary Texts", Women and Religion in the Ancient Near East and Asia, edited by Nicole Maria Brisch and Fumi Karahashi, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 93-120, 2023

- ^ Ga’eš year names at CDLI

- ^ Sallaberger, W., "Der Kultische Kalender der Ur ril-Zeit Teill", Untersuchungen zur Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archaologie 7/1, Berlin, 1993

- ^ Stol, Marten, "Priestesses", Women in the Ancient Near East, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 555-583, 2016

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "The Reluctant En of Inana — or the Persona of Gilgameš in the Perspective of Babylonian Political Philosophy", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 5, no. 1-2, pp. 149-177, 2018

- ^ Carroue, F., "Etudes de Geographie et de Topographie Sumeriennes III. L'lturungal et le Sud Sumerien", Acta Sumerologica 15, pp. 11-69, 1993

- ^ Sallaberger, W., Schrakamp, I., "History and Philology", ARCANE III, Turnhout, 2015

- ^ Douglas Frayne, "Larsa", Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 107-322, 1990

- ^ Owen, David I., "Transliterations, Translations, and Brief Comments", The Nesbit Tablets, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 13-110, 2016

- ^ Helle, Sophus, "The Temple Hymns", Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 53-94, 2023

- ^ "CDLI Literary 000380 (Lament for Sumer and Ur) Composite Artifact Entry", (2014) 2024. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI), July 15, 2024

- ^ Kröll, N., & Fink, S.,"How to Destroy Sanctity? Some Insights from Sumerian Cuneiform Texts", in The Human and the Divine, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 124-147, 2025

- ^ [16] D'Agostino, Franco, and Angela Greco, "Abu Tbeirah. philological and epigraphic point of view", Abu Tbeirah. Excavations I. Area 1. Last Phase and Building A – Phase 1, pp. 465-477, 2019

- ^ "The so-called Second Dynasty of Ur is a phantom and is not recorded in the SKL" in Frayne, Douglas (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). University of Toronto Press. p. 910. ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9.

- ^ Woolley, Leonard; Hall, Henry; Legrain, L. (1900). Ur excavations (Report). Vol. II. Trustees of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. ISBN 9780598629883.

{{cite report}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) Alt URL - ^ Aruz, J.; Wallenfels, R. (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art Series. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300098839.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Marchesi, Gianni (January 2015). Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (eds.). "Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia". History and Philology (ARCANE 3; Turnhout): 139–156.

- ^ "Queen Puabi's Headdress from the Royal Cemetery at Ur". Penn Museum. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

Further reading

[edit]- [17] Benati, Giacomo, "Re-modeling political economy in early 3rd millennium BC Mesopotamia: patterns of socio-economic organization in Archaic Ur (Tell al-Muqayyar, Iraq)", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2015.2, 2015

- Benati, Giacomo, "The Beginning of the Early Dynastic Period at Ur", Iraq, vol. 76, 2014, pp. 1–17, 2014

- Black, J. and Spada, G., "Texts from Ur: Kept in the Iraq Museum and the British Museum.", Nisaba 19, Messina: Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichitá 2008 ISBN 9788882680107

- [18] Chambon, Grégory "Archaic metrological systems from Ur", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2003.5, 2003

- D. Charpin, "Le Clergé d'Ur au siècle d'Hammurabi (XIXe-XVIIIe siècles av. J.-C.)", HEO 22, Geneva-Paris, 1986

- D. Charpin, "Le pillage d'Ur et la protection du temple de Ningal en l'an 12 de Samsu-iluna", in: D. Charpin (ed.), Archibab 4. Nouvelles recherches sur la ville d'Ur à l'époque paléo babylonienne, Mémoires de NABU 22, Paris, 2019

- Charvát, Petr, "Signs from Silence: Ur of the First Sumerians (Late Uruk Through ED I)", Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016, edited by Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 195–204, 2021

- Crawford, Harriet, "Ur: The City of the Moon God", London: Bloomsbury, 2015. ISBN 978-1-47252-419-5

- D’Agostino, F., Pomponio, F., and Laurito, R., "Neo-Sumerian Texts from Ur in the British Museum.", Nisaba 5, Messina: Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichitá, 2004 ISBN 9788882680107

- C. J. Gadd, "History and monuments of Ur, Chatto & Windus", 1929 (Dutton 1980 reprint: ISBN 0-405-08545-1).

- [19] Leon Legrain, "Archaic seal-impressions", Ur Excavations III, Publications of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, to Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1936

- [20] Leon Legrain, "Seal cylinders", Ur Excavations X, Publications of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, to Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1951

- P. R. S. Morrey, "Where Did They Bury the Kings of the IIIrd Dynasty of Ur?", Iraq, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 1–18, 1984.

- [21] P.R.S. Morrey, "What Do We Know About the People Buried in the Royal Cemetery?", Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum, vol. 20, iss. 1, pp. 24–40, 1977

- [22]Notizia, Palmiro, "The Burial Pit of the ensi₂ of Gizuna (ŠID. NUNki) and the Cemetery of Ur Between the Late Early Dynastic and Early Sargonic Periods", KASKAL, pp. 23-32, 2024

- J. Oates, "Ur and Eridu: The Prehistory", Iraq, vol. 22, pp. 32–50, 1960.

- Pardo Mata, Pilar, "Ur, ciudad de los sumerios". Cuenca: Alderaban, 2006. ISBN 978-84-95414-38-0.

- Susan Pollock, "Chronology of the Royal Cemetery of Ur", Iraq, vol. 47, pp. 129–158, British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 1985

- Susan Pollock, "Of Priestesses, Princes and Poor Relations: The Dead in the Royal Cemetery of Ur", Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol. 1, iss. 2, 1991

- Wencel, M. M., "New radiocarbon dates from southern Mesopotamia (Fara and Ur)", Iraq, 80, pp. 251–261, 2018

- [23] Woolley, Leonard, "The Royal Cemetery: a report on the predynastic and Sargonid graves excavated between 1926 and 1931", Ur Excavations II, Publications of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, to Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1927

- [24] Woolley, Leonard, "The early periods: a report on the sites and objects prior in date to the third dynasty of Ur discovered in the course of the excavations", Ur excavations IV, London : Published for the Trustees of the Two Museums, Oxford University Press, 1955

- [25] Woolley, Leonard, "The Ziggurat and Its Surroundings", Ur Excavations V, Oxford University Press, 1939

- [26] Woolley, Leonard, "The buildings of the third dynasty", Ur Excavations VI, London : Published for the Trustees of the Two Museums, 1974

- [27] Woolley, Leonard and with M.E.L. Mallowan, "The Old Babylonian Period", Ur Excavations VII, Oxford University Press, 1976

- [28] Woolley, Leonard, "The Kassite period and the period of the Assyrian kings", Ur Excavations VIII, London : Published for the Trustees of the Two Museums, 1965

- [29] Woolley, Leonard and M.E.L. Mallowan, "The Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods", Ur Excavations IX, London : Published for the Trustees of the Two Museums, 1962

- [30] Woolley, Leonard, "Ur of the Chaldees: A record of seven years of excavation", Ernest Benn Limited, 1920

- C. L. Woolley, "The Excavations at Ur, 1923–1924", Antiquaries Journal 5, pp. 1–20, 1925

- C. L. Woolley, "The Excavations at Ur, 1924–1925", Antiquaries Journal 5, pp. 347–402, 1925

- C. L. Woolley, "The Excavations at Ur, 1925–1926", Antiquaries Journal 6, pp. 365–401, 1926

- C. L. Woolley, "The Excavations at Ur, 1926–1927", Antiquaries Journal 7, pp. 385–423, 1927

- C. L. Woolley, "Excavations at Ur, 1927–1928", Antiquaries Journal 8, pp. 415–448, 1928

- C. L. Woolley, "Excavations at Ur, 1928–1929", Antiquaries Journal 9, pp. 305–343, 1929

- C. L. Woolley, "Excavations at Ur, 1929–1930", Antiquaries Journal 10, pp. 315–343 and pl. XXVIII, 1930

- C. L. Woolley, "Excavations at Ur, 1930–1931", Antiquaries Journal 11, pp. 343–381, 1931

- C. L. Woolley, "Excavations at Ur, 1931–1932", Antiquaries Journal 12, pp. 355–392 and pl. LVIII, 1932

External links

[edit]- City of the Moon New Excavations at Ur – Penn Museum – 2017

- An exploration of the Royal Tombs of Ur, with a comprehensive selection of high-resolution photographs detailing the treasures found in the tombs

- Explore some of the Royal Tombs, Mesopotamia website from the British Museum

- Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur Archived 2008-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- British Museum and Penn Museum Ur site – has field reports

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Ur

- Woolley’s Ur Revisited, Richard L. Zettler, BAR 10:05, September/October 1984.

- Ur Excavations of the University of Pennsylvania Museum

- At Ur, Ritual Deaths That Were Anything but Serene on The New York Times

Geography and Environment

Location and Topography

Ur is located at the site of Tell al-Muqayyar in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq, at coordinates 30°57′45″N 46°06′11″E, approximately 16 kilometers southwest of the modern city of Nasiriyah.[2] [3] The site lies on the alluvial plain of southern Mesopotamia, characterized by flat, low-lying terrain formed by sediment deposits from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, with elevations near sea level.[2] The ancient city occupies a prominent tell, or mound, resulting from millennia of occupational debris accumulation, measuring roughly 1,200 meters northwest-southeast by 800 meters northeast-southwest and rising up to 20 meters above the surrounding plain.[4] This elevated platform supported key structures, including the ziggurat of the moon god Nanna, and provided defense against seasonal flooding in the riverine environment.[5] In Sumerian times, around the third millennium BCE, Ur was positioned near the Euphrates River's mouth, directly adjacent to the Persian Gulf, enabling it as a major port for maritime commerce; subsequent silting of the river and delta progradation has shifted the coastline southward, rendering the site now about 10 kilometers west of the Euphrates and over 200 kilometers inland from the Gulf.[4] [6]Riverine and Climatic Context

Ur lay along the Euphrates River in southern Mesopotamia, near its outlet to the Persian Gulf around 2500 BCE. This position enabled irrigation agriculture and supported trade through riverine and maritime routes.[7] Branches of the river ran through the city, with paleochannels defining ancient suburbs and harbors, as revealed by aerial and satellite imagery analysis.[1] Avulsions shifted the river's course eastward between 2500 and 2000 BCE, leaving the site now about 16 km inland from the Shatt al-Arab.[7] The region has a semi-arid climate with hot, dry summers exceeding 40°C, mild winters averaging 10–15°C, and annual rainfall of 100–250 mm, mostly from November to April.[8] Seasonal flooding and engineered irrigation networks were essential to sustain crop yields in the alluvial soils, driving Ur's prosperity.[9] Unpredictable floods and droughts, however, challenged these systems and influenced settlement patterns and resource management.[10]Etymology and Historical Names

Sumerian and Akkadian Designations

In Sumerian texts, the city now known as Ur was designated Urim, written in cuneiform as URIM𒋀𒀊𒆠, under the patronage of the moon god Nanna.[11] The name appears in administrative and royal inscriptions from the Early Dynastic period onward, reflecting its role as a major urban center in southern Mesopotamia.[12] The etymology of Urim remains uncertain, though it may derive from the Sumerian ur or uru, meaning "city" or "abode."[13] Akkadian sources adapted the name to Uru, preserving phonetic similarity under Semitic conventions during periods of Akkadian influence, such as the Sargonic Empire (c. 2334–2154 BCE).[11] This form appears in bilingual texts and royal annals, illustrating linguistic continuity amid shifts from Sumerian to Akkadian dominance.[14] Some interpretations link Urim to "the shining city" or Nanna's luminous attributes, but these lack direct cuneiform evidence and rely on associative rather than philological analysis.[15]Later References

In Mesopotamian texts from the Old Babylonian period onward—including Kassite, Assyrian, and Neo-Babylonian eras—the city was known as Uru or Uri, cuneiform variants of the earlier Sumerian Urim. Neo-Babylonian inscriptions, such as those from Nabonidus (556–539 BCE), consistently use Uru and record restorations to the ziggurat and temples of the moon god Nanna/Sin.[16] This continuity reflects enduring local usage despite political changes, with Ur serving as a provincial center under Babylonian control.[17] The Hebrew Bible refers to it as ʾŪr Kaśdīm (Ur of the Chaldees), naming it as Abraham's birthplace in Genesis 11:28, 31; 15:7; and Nehemiah 9:7. The term Kaśdīm denotes the Chaldean tribes that dominated southern Mesopotamia from the 9th century BCE, especially during the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BCE). Scholars view this specifier as a later redaction, since the Chaldeans rose to prominence long after Ur's Early Dynastic and Ur III peaks (ca. 2600–2000 BCE) but controlled the region—including Tell el-Muqayyar—by the 8th–6th centuries BCE, aiding geographic identification for exilic or post-exilic readers.[18] Archaeological and textual evidence supports linking this to southern Babylonian Ur, though a minority view proposes northern sites such as Urfa based on Genesis migration routes; most data favors the Muqayyar location. Classical Greek sources rarely mention Ur by name, as the city had declined in prominence by the Achaemenid Persian (539–330 BCE) and Hellenistic periods. Historians like Herodotus addressed broader Babylonian geography rather than specific Sumerian sites. Berossus, a 3rd-century BCE Babylonian priest writing in Greek, refers to Mesopotamian cities and kings but does not single out Ur, underscoring its reduced visibility after the Neo-Babylonian era.[19]Prehistoric Development

Ubaid Period Settlements

Archaeological evidence shows that Ur was first settled during the Early Ubaid period, around 5500–5000 BC, as permanent village communities emerged in southern Mesopotamia.[1] Leonard Woolley's early 20th-century excavations uncovered Ubaid layers beneath later strata, revealing tripartite mud-brick houses used for domestic activities such as food processing and storage.[20] These early settlements remained small, typically under 4 hectares, with self-sufficient households focused on subsistence agriculture—including cultivation of barley and emmer wheat—supported by basic irrigation channels from nearby waterways.[21] By the Late Ubaid phase (c. 4500–4000 BC), Ur expanded to about 10 hectares, comparable to sites like Eridu, with denser occupation and possible communal structures for ritual or administrative functions.[1] [21] Pottery from these levels includes painted buff wares with geometric motifs and Coba bowls, reflecting regional cultural continuity alongside local adaptations to the floodplain setting.[22] Beveled-rim bowls found in Woolley's trenches suggest early standardization in production, potentially linked to organized labor for irrigation maintenance.[2] Burial practices featured flexed inhumations in simple pits, often accompanied by grave goods such as shell beads and copper tools, indicating emerging social differentiation through access to materials from the Persian Gulf.[1] Environmental evidence from nearby sites points to a wetter climate phase with fertile alluvial soils that supported flood-based farming, though risks of salinization were already present.[20] The transition to the Uruk period at Ur displayed continuity in settlement layout, with Ubaid houses gradually developing into more complex compounds, reflecting steady intensification rather than sudden change.[23]Historical Periods

Early Dynastic Era

The Early Dynastic period (c. 2900–2350 BCE) marked the maturation of Ur as a Sumerian city-state, with temple-palace institutions centralizing economic and political control amid competition among roughly 20–30 regional powers.[24] Population growth to over 200,000 in southern Mesopotamia supported urban expansion, with Ur featuring large settlements exceeding 40 hectares.[24] The First Dynasty of Ur commenced with Mesannepada, identified as the foundational ruler through contemporary seals and later king lists, contemporary with Eannatum of Lagash who briefly conquered the city.[25] Subsequent kings included Mes-kiagnuna, Elulu, and Balulu, though reign lengths in textual sources like the Sumerian King List—such as 80 years for Mesannepada—are likely exaggerated for legendary effect.[25] Seals of Meskalamdug and Akalamdug from royal contexts suggest familial or dynastic continuity, linking rulers to military campaigns and divine patronage under the moon god Nanna.[25] Archaeological evidence from the Royal Cemetery, spanning Early Dynastic IIIA (c. 2600–2500 BCE) and comprising about 660 burials including 16 elite tombs, attests to Ur's wealth and ritual sophistication.[25][26] These featured vaulted chambers stocked with gold, silver, lapis lazuli jewelry, copper weapons, and musical instruments, alongside "death pits" containing 6–74 human attendants sacrificed to accompany the deceased, indicating a hierarchical society where elites held semi-divine status.[26][25] Prominent interments include Queen Puabi's tomb (PG 800), equipped with a headdress, cylinder seal, and banquet wares, and PG 755 of Meskalamdug, yielding a gold helmet and weapons symbolizing martial prowess.[26] Artifacts like the Standard of Ur, inlaid with shell, lapis, and limestone mosaics depicting warfare, chariots, and captives on one side alongside peaceful banqueting on the other, illustrate the era's militarism and tributary economy.[25] Ur's prosperity derived from irrigated barley and date cultivation, sheep-goat herding, and trade networks importing copper, tin, and lapis lazuli from afar, managed by temple estates that owned land and mobilized labor.[24] Rulers, evolving from priestly to hereditary kings, mediated between divine cults and assemblies, fostering stability until external conquests disrupted the dynasty c. 2350 BCE.[24]Akkadian and Gutian Interregnum

After Sargon of Akkad conquered Ur around 2334 BC, the city was incorporated into the Akkadian Empire, establishing the first centralized imperial rule over southern Mesopotamia. Ur served as a major provincial center, where Akkadian governors handled administration, taxation, and military duties, while temples to the moon god Nanna preserved Sumerian religious traditions despite Akkadian becoming the official administrative language.[27] Standardization of weights, measures, and cuneiform script under rulers such as Rimush and Naram-Sin supported Ur’s integration into empire-wide trade networks, including imports of lapis lazuli from the east and timber. Archaeological evidence shows growing Semitic influences in pottery and seals, yet urban infrastructure remained largely intact.[4][1] The Akkadian Empire collapsed amid internal revolts, Elamite attacks, and severe aridification around 2200 BC, leading to the Gutian invasion circa 2154 BC. Originating from the Zagros Mountains, the Gutians established loose overlordship focused on tribute collection with limited administrative control. The Sumerian King List records 21 Gutian rulers whose reigns averaged less than five years each.[28][29] This interregnum (c. 2154–2113 BC) led to regional fragmentation and economic decline in Sumerian city-states like Ur, as evidenced by reduced textual records and diminished temple endowments. In Ur itself, Gutian influence appears in fifteen high-status burials dated 2150–2100 BC, containing distinctive artifacts that suggest elite Gutian settlers or allies integrated into local hierarchies. Sumerian officials likely continued to govern locally under Gutian suzerainty, paying tribute while retaining some autonomy. The period brought reduced monumental building, lower agricultural production, famine, and social instability—later condemned in Sumerian laments as rule by “mountain shepherds” unfamiliar with urban governance.[30][31] The Gutian period ended when Utu-hengal of Uruk defeated the final Gutian king, Tirigan, around 2113 BC, paving the way for Ur’s revival under Ur-Nammu.[28]Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–2004 BCE, middle chronology) revived Sumerian power in southern Mesopotamia after the Gutian interregnum. Ur-Nammu, governor of Ur under Utu-hengal of Uruk, defeated the Gutians around 2112 BCE and founded the dynasty, creating a centralized empire covering Sumer, Akkad, and parts of Elam. Over 65,000 cuneiform tablets from sites such as Umma and Girsu document an advanced bureaucracy that tightly controlled labor, agriculture, and resources.[32][33][34] Ur-Nammu (r. 2112–2095 BCE) built the Great Ziggurat of Ur dedicated to the moon god Nanna, a 30-meter-high stepped platform of baked bricks. He issued the Code of Ur-Nammu, the earliest known legal code, which featured a prologue and laws emphasizing restitution for offenses such as murder or theft over retribution.[35][36] His successor Shulgi (r. 2094–2047 BCE) expanded the empire through military campaigns, deified himself to strengthen absolute rule, and reformed administration by standardizing weights, measures, and a decimal-based taxation system. His reign produced royal hymns praising his divinity, scholarly works, and extensive canal construction that improved irrigation and increased yields of barley and dates.[33][37] Later rulers Amar-Sin (r. 2046–2038 BCE) and Shu-Sin (r. 2037–2029 BCE) preserved the bureaucratic system. Amar-Sin focused on temple construction, while Shu-Sin built the "Amorite Wall," a 270-kilometer defense against western incursions. The economy centered on state-directed agriculture through temple and palace estates, using corvée labor for irrigation and harvesting, and supplemented by trade in metals, timber, and lapis lazuli. Administrative records show provincial ensi governors reporting to Ur, with detailed tracking of grain, wool, and livestock to curb corruption.[32][37][38] Decline set in under Ibbi-Sin (r. 2028–2004 BCE) amid drought, soil salinization, heavy taxation, unrest, and external pressures. Elamite forces exploited these weaknesses, sacking Ur around 2004 BCE and capturing Ibbi-Sin, which fragmented the empire into smaller states such as Isin and Larsa. This collapse ended Sumerian dominance and shifted Mesopotamia toward Amorite and Babylonian influences, although Ur III administrative innovations influenced later empires.[39][37][32]Post-Ur III Decline

The Third Dynasty of Ur collapsed around 2004 BCE when Elamite forces under the Simashki ruler Kindattu invaded southern Mesopotamia, sacked Ur, and captured its final king, Ibbi-Sin (r. ca. 2028–2004 BCE).[32] [40] This defeat followed prolonged internal pressures, including administrative overextension, droughts, and Amorite incursions, which had already weakened control over outlying provinces—as shown in administrative texts and royal letters requesting grain shipments during famines.[41] The sack ended Sumerian imperial dominance and reduced Ur to a subordinate city-state in a fragmented political landscape.[32] During the ensuing Isin-Larsa period (ca. 2004–1763 BCE), Ur lost its political independence. It first came under the Dynasty of Isin, established by Ishbi-Erra (a former governor under Ibbi-Sin) around 2017 BCE.[40] Kings of Isin, such as Lipit-Ishtar (ca. 1934–1924 BCE), retained some authority over Ur’s temples and economy, with evidence of temple maintenance and local administration. However, Ur functioned primarily as a regional cult center rather than an administrative hub.[42] By the mid-20th century BCE, Larsa rose under Gungunum (ca. 1932–1906 BCE) and incorporated Ur into its sphere of influence. Archaeological layers from this era show continued occupation on a reduced scale, including merchants’ houses but less monumental construction than in Ur III times.[43] Archaeological evidence indicates no complete abandonment after the sack. Instead, Ur experienced population decline and a shift toward local trade and agriculture, compounded by ongoing salinization in irrigation canals that reduced crop yields.[44] The ziggurat and Nanna temple remained active religious centers, supported by endowments from later rulers. Yet Ur’s influence steadily diminished amid competition from emerging powers such as Babylon, leading to greater marginalization in the Old Babylonian period.[4] This decline stemmed from broader factors—ecological stress and the unsustainability of Ur III’s centralized bureaucracy—beyond mere external conquest.[41]Governance and Rulers

Dynastic Structures