Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

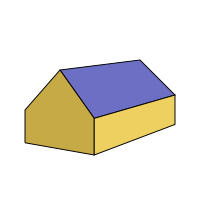

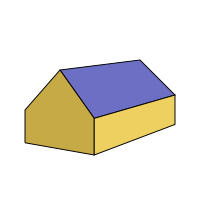

Gable roof

View on Wikipedia

A gable roof[1] is a roof consisting of two sections whose upper horizontal edges meet to form its ridge. The most common roof shape in cold or temperate climates, it is constructed of rafters, roof trusses or purlins. The pitch of a gable roof can vary greatly.

Distribution

[edit]The gable roof[2] is so common because of the simple design of the roof timbers and the rectangular shape of the roof sections. This avoids details which require a great deal of work or cost and which are prone to damage. If the pitch or the rafter lengths of the two roof sections are different, it is described as an 'asymmetrical gable roof'. A gable roof on a church tower (gable tower) is usually called a 'cheese wedge roof' (Käsbissendach) in Switzerland.

Its versatility means that the gable roof is used in many regions of the world.[3] In regions with strong winds and heavy rain, gable roofs are built with a steep pitch in order to prevent the ingress of water. By comparison, in alpine regions, gable roofs have a shallower pitch which reduces wind exposure and supports snow better, reducing the risk of an uncontrolled avalanche and more easily retaining an insulating layer of snow.[4]

Gable roofs are most common in cold climates. They are the traditional roof style of New England and the east coast of Canada. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables and Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, the authors of which are from these respective regions, both reference this roof style in their titles.[5]

Pros and cons

[edit]Gable roofs have several advantages.[6] They are:

- Inexpensive

- May be designed in many different ways.

- Are based on a simple design principle.[7]

- More weather-resistant than flat roofs

- May allow an attic to be turned into living space if the pitch is sufficient to at least allow dormers. A steeper pitch will be sufficient on its own.

Disadvantages:

German terminology

[edit]In German-speaking countries, the types of gable roof are referred to as:

- Shallow gable roof (flaches Satteldach) with a pitch of ≤ 30°

- New German (neudeutsches Dach) or angled roof (Winkeldach) with a pitch of 45°

- When the pitch it greater than 62° it is called a Gothic (gotisches) or Old German roof (altdeutsches Dach)

- If the roof has the shape of an equilateral triangle and 60° pitch it is called an Old Franconian (altfränkisches) (commonly found in the region of Franconia) or Old French roof (altfranzösisches Dach)[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fritz Baumgart: DuMont’s kleines Sachlexikon der Architektur. Cologne, 1977.

- ^ "Your Guide to Gable Roof – House Discreet". Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved 2022-05-13.

- ^ Davidorr, Robert. "What Is A Gable Roof? Everything You Need To Know". remodelreality.com. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Herrera, Paulo. Learn that word.

- ^ "Hip Roof vs. Gable Roof". IKO website. IKO Industries Ltd. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ "Informationen rund ums Satteldach. Retrieved 20 June 2012". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "Satteldach: Die einfache Konstruktion hat sich bewährt. Retrieved 20 June 2012". Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680-1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. p. 106. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- ^ Willibald Mannes, Franz-Josef Lips-Ambs: Dachkonstruktionen in Holz, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1981, ISBN 3-421-03283-1.