Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

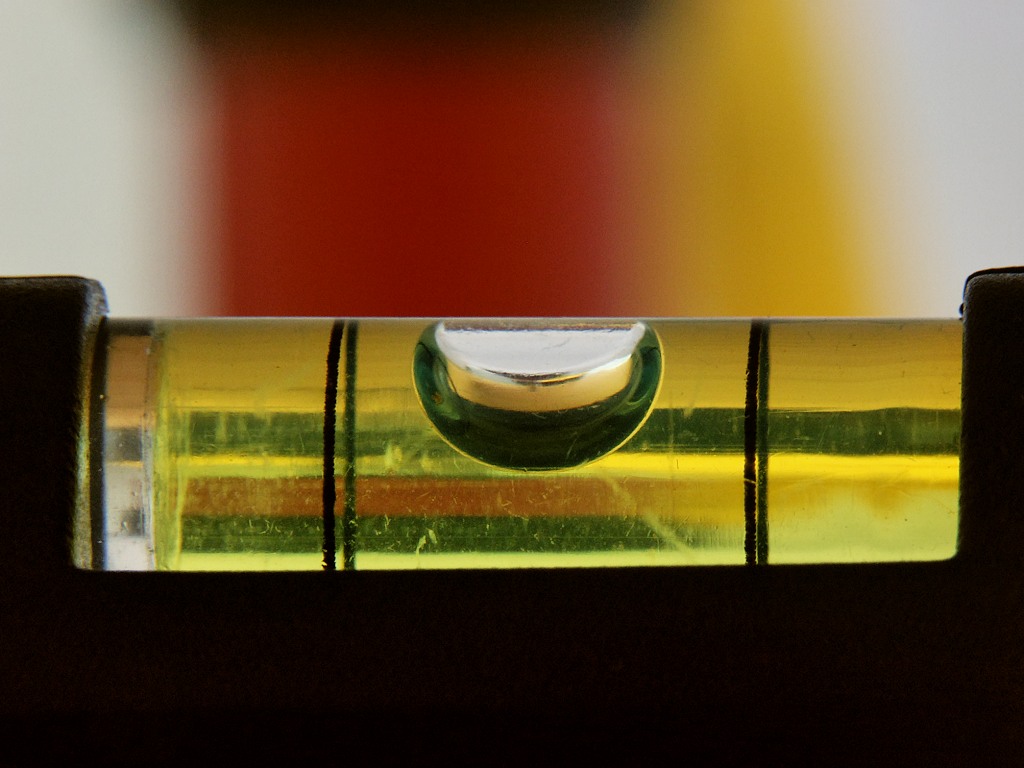

Spirit level

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

A spirit level, bubble level, or simply a level, is an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is horizontal (level) or vertical (plumb). It is called a "spirit level" because the liquid inside its vial is commonly alcohol, or "spirit". The name refers to this alcohol-based solution, which, along with an air bubble, indicates whether a surface is level or plumb. Alcohol was historically preferred over water because it has a wider temperature range, won't freeze, and provides less friction for the bubble, ensuring greater accuracy and longevity of the tool. Two basic designs exist: tubular (or linear) and bull's eye (or circular). Different types of spirit levels may be used by carpenters, stonemasons, bricklayers, other building trades workers, surveyors, millwrights and other metalworkers, and in some photographic or videographic work.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

The history of the spirit level was discussed in brief in an 1887 article appearing in Scientific American.[1] Melchisédech Thévenot, a French scientist, invented the instrument some time before February 2, 1661. This date can be established from Thevenot's correspondence with scientist Christiaan Huygens. Within a year of this date the inventor circulated details of his invention to others, including Robert Hooke in London and Vincenzo Viviani in Florence. It is occasionally argued that these "bubble levels" did not come into widespread use until the beginning of the 18th century — the earliest surviving examples being from that time — but Adrien Auzout had recommended that the Académie Royale des Sciences take "levels of the Thevenot type" on its expedition to Madagascar in 1666. It is very likely that these levels were in use in France and elsewhere long before the turn of the century.

The Fell All-Way precision level, one of the first successful American made bull's eye levels for machine tool use, was invented by William B. Fell of Rockford, Illinois in 1939.[2] The device was unique in that it could be placed on a machine bed and show tilt on the x-y axes simultaneously, eliminating the need to rotate the level 90 degrees. The level was so accurate it was restricted from export during World War II. The device set a new standard of .0005 inches per foot resolution (five ten thousands per foot or five arc seconds tilt). Production of the level stopped around 1970, and was restarted in the 1980s by Thomas Butler Technology, also of Rockford, Illinois, but finally ended in the mid-1990s. However, there are still hundreds of the devices in existence.

Design and construction

[edit]

Early tubular spirit levels had very slightly curved glass vials with constant inner diameter at each viewing point. These vials are filled, incompletely, with a liquid — usually a colored spirit or alcohol — leaving a bubble in the tube. They have a slight upward curve, so that the bubble naturally rests in the center, the highest point. At slight inclinations the bubble travels away from the marked center position. Where a spirit level must also be usable upside-down or on its side, the curved constant-diameter tube is replaced by an uncurved barrel-shaped tube with a slightly larger diameter in its middle.

Alcohols such as ethanol are often used rather than water. Alcohols have low viscosity and surface tension, which allows the bubble to travel the tube quickly and settle accurately with minimal interference from the glass surface. Alcohols also have a much wider liquid temperature range, and will not break the vial as water could due to ice expansion. A colorant such as fluorescein, typically yellow or green, may be added to increase the visibility of the bubble.

A variant of the linear spirit level is the bull's eye level: a circular, flat-bottomed device with the liquid under a slightly convex glass face with a circle at the center. It serves to level a surface across a plane, while the tubular level only does so in the direction of the tube.

Calibration

[edit]

To check the accuracy of a carpenter's type level, a perfectly horizontal surface is not needed. The level is placed on a flat and roughly level surface and the reading on the bubble tube is noted. This reading indicates to what extent the surface is parallel to the horizontal plane, according to the level, which at this stage is of unknown accuracy. The spirit level is then rotated through 180 degrees in the horizontal plane, and another reading is noted. If the level is accurate, it will indicate the same orientation with respect to the horizontal plane. A difference implies that the level is inaccurate.

Adjustment of the spirit level is performed by successively rotating the level and moving the bubble tube within its housing to take up roughly half of the discrepancy, until the magnitude of the reading remains constant when the level is flipped.

A similar procedure is applied to more sophisticated instruments such as a surveyor's optical level or a theodolite and is a matter of course each time the instrument is set up. In this latter case, the plane of rotation of the instrument is levelled, along with the spirit level. This is done in two horizontal perpendicular directions.

Sensitivity

[edit]Sensitivity is an important specification for a spirit level, as the device's accuracy depends on its sensitivity. The sensitivity of a level is given as the change of angle or gradient required to move the bubble by unit distance. If the bubble housing has graduated divisions, then the sensitivity is the angle or gradient change that moves the bubble by one of these divisions. 2 mm (0.079 in) is the usual spacing for graduations; on a surveyor's level, the bubble will move 2 mm (0.079 in) when the vial is tilted about 0.005 degree. For a precision machinist level with 2 mm (0.079 in) divisions, when the vial is tilted one division, the level will change 0.04 mm (0.0016 in) one meter from the pivot point, referred to by machinists as 5 tenths per foot. This terminology is unique to machinists and indicates a length of 5 tenths of 1 thousandth of an inch.[3][4]

Types

[edit]

There are different types of spirit levels for different uses:

- Carpenter's level (either wood, aluminium or composite materials)

- Mason's level

- Torpedo level — a level with a torpedo-shaped frame with vertical, horizontal, and sometimes 45° tube levels

- Post level

- Line level

- Engineer's precision level

- Electronic level

- Inclinometer

- Slip or skid indicator

- Bull's eye level

A spirit level is usually found on the head of combination squares.

Carpenter's level

[edit]

A traditional carpenter's spirit level looks like a short plank of wood and often has a wide body to ensure stability, and that the surface is being measured correctly. In the middle of the spirit level is a small window where the bubble and the tube is mounted. Two notches (or rings) designate where the bubble should be if the surface is level. Often an indicator for a 45 degree inclination is included.[citation needed]

Engineer's precision levels

[edit]An engineer's precision level permits leveling items to greater accuracy than a plain spirit level. They are used to level the foundations, or beds of machines to ensure the machine can output workpieces to the accuracy pre-built in the machine.

Line level

[edit]

A line level is a level designed to hang on a builder's string line. The body of the level incorporates small hooks to allow it to attach and hang from the string line. The body is lightweight, so as not to weigh down the string line, and small in size as the string line in effect becomes the body; when the level is hung in the center of the string, each 'leg' of the string line extends the level's plane.

Torpedo level

[edit]

A torpedo level is a level enclosed inside of a roughly torpedo-shaped frame with small vertical, horizontal, and sometimes 45° tube levels. Torpedo levels are especially useful in small spaces. The frames are usually made of plastic or metal.[5]

Surveyor's leveling instrument

[edit]

Combining a spirit level with an optical telescope results in a tilting level or dumpy level.[6] These leveling instruments as used in surveying to measure height differences over larger distances. A surveyor's leveling instrument has a spirit level mounted on a telescope (perhaps 30 power) with cross-hairs, itself mounted on a tripod. The observer reads height values off two graduated vertical rods, one 'behind' and one 'in front', to obtain the height difference between the ground points on which the rods are resting. Starting from a point with a known elevation and going cross country (successive points being perhaps 100 meters (328 ft) apart) height differences can be measured cumulatively over long distances and elevations can be calculated. Precise levelling is supposed to give the difference in elevation between two points one kilometer (0.62 miles) apart correct to within a few millimeters.

Alternatives

[edit]Alternatives include:

- Cross laser level or line laser level, a type of modern electronic laser levels commonly used in construction and home projects

- Rotary laser level, with a rotating, strong laser dot suitable for outdoor use

- Reed level

- Water level

Today level tools are available in most smartphones by using the device's accelerometer. These mobile apps come with various features and easy designs.[7] Also new web standards allow websites to get orientation of devices.

Digital spirit levels are increasingly common in replacing conventional spirit levels, particularly in civil engineering applications such as traditional building construction and steel structure erection, for on-site angle alignment and leveling tasks. The industry practitioners often refer to those levelling tools as a "construction level", "heavy duty level", "inclinometer", or "protractor". These modern electronic levels are capable of displaying precise numeric angles within 360° with 0.1° to 0.05° accuracy, can be read from a distance with clarity, and are affordably priced due to mass adoption. They provide features that traditional levels are unable to match. Typically, these features enable steel beam frames under construction to be precisely aligned and levelled to the required orientation, which is vital to ensure the stability, strength and rigidity of steel structures on sites. Digital levels, embedded with angular MEMS technology effectively improve productivity and quality of many modern civil structures. Some recent models feature waterproof IP65 and impact resistance features for harsh working environments.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Scientific American. Munn & Company. 1887-08-27. p. 136.

- ^ William B Fell (1940-08-01). "Machinist's precision level (US2316777A)". Google Patents. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Beginner's Guide to Reading Machine Shop Numbers & Values". 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Sensitivity & Accuracy of Spirit Level Vials". 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Small Torpedo Levels: The Ultimate Level for Tight Spaces". Keson. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2025.

- ^ "Equipment Database Menu". Sli.unimelb.edu.au. 1998-10-19. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "How do I access the spirit level?". iPhoneFAQ. Retrieved 2 August 2018.