Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

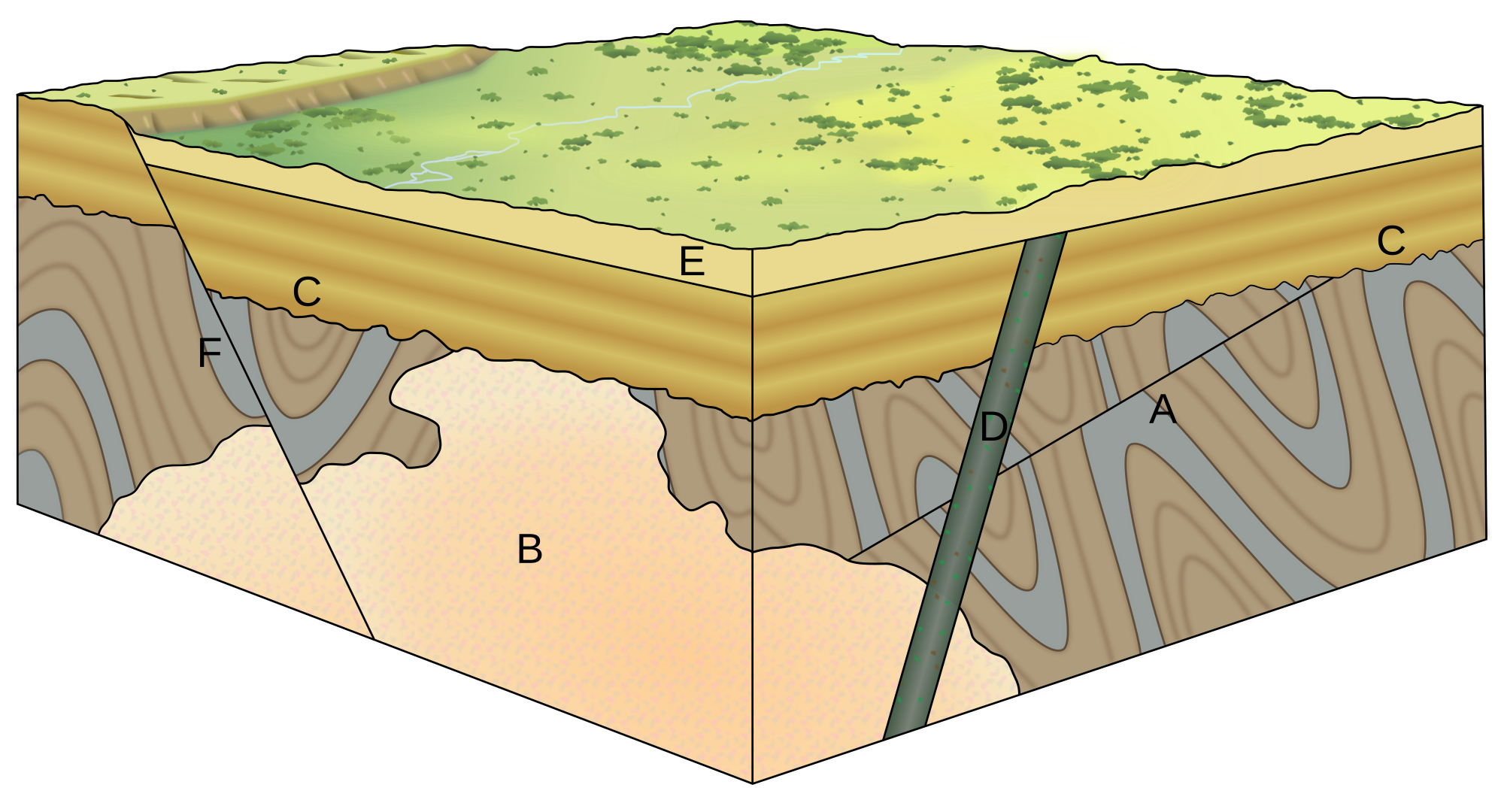

Cross-cutting relationships

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (July 2012) |

Cross-cutting relationships is a principle of geology that states that the geologic feature which cuts another is the younger of the two features. It is a relative dating technique in geology. It was first developed by Danish geological pioneer Nicholas Steno in Dissertationis prodromus (1669) and later formulated by James Hutton in Theory of the Earth (1795) and embellished upon by Charles Lyell in Principles of Geology (1830).

Types

[edit]There are several basic types of cross-cutting relationships:

- Structural relationships may be faults or fractures cutting through an older rock.

- Intrusional relationships occur when an igneous pluton or dike is intruded into pre-existing rocks.

- Stratigraphic relationships may be an erosional surface (or unconformity) cuts across older rock layers, geological structures, or other geological features.

- Sedimentological relationships occur where currents have eroded or scoured older sediment in a local area to produce, for example, a channel filled with sand.

- Paleontological relationships occur where the animal activity or plant growth produces truncation. This happens, for example, when animal burrows penetrate into pre-existing sedimentary deposits.

- Geomorphological relationships may occur where a surficial feature, such as a river, flows through a gap in a ridge of rock. In a similar example, an impact crater excavates into a subsurface layer of rock.

Cross-cutting relationships may be compound in nature. For example, if a fault were truncated by an unconformity, and that unconformity cut by a dike. Based upon such compound cross-cutting relationships it can be seen that the fault is older than the unconformity which in turn is older than the dike. Using such rationale, the sequence of geological events can be better understood.

Scale

[edit]Cross-cutting relationships may be seen cartographically, megascopically, and microscopically. In other words, these relationships have various scales. A cartographic crosscutting relationship might look like, for example, a large fault dissecting the landscape on a large map. Megascopic cross-cutting relationships are features like igneous dikes, as mentioned above, which would be seen on an outcrop or in a limited geographic area. Microscopic cross-cutting relationships are those that require study by magnification or other close scrutiny. For example, penetration of a fossil shell by the drilling action of a boring organism is an example of such a relationship.

Other use

[edit]Cross-cutting relationships can also be used in conjunction with radiometric age dating to effect an age bracket for geological materials that cannot be directly dated by radiometric techniques. For example, if a layer of sediment containing a fossil of interest is bounded on the top and bottom by unconformities, where the lower unconformity truncates dike A and the upper unconformity truncates dike B (which penetrates the layer in question), this method can be used. A radiometric age date from crystals in dike A will give the maximum age date for the layer in question and likewise, crystals from dike B will give us the minimum age date. This provides an age bracket, or range of possible ages, for the layer in question.

Gallery

[edit]-

Cross-cutting relationships involving an andesitic dike in Peru that cuts across the lower sedimentary strata. Both the dike and the lower strata are cut by an unconformity

-

Dike below Puray Falls in Rodriguez, Rizal Philippines intruding pinkish-brown trachyte

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Cross Cutting. World of Earth Science. Ed. K. Lee Lerner and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner. Gale Cengage, 2003.

- Nicolai Stenonis solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus ... Florentiae : ex typographia sub signo Stellae (1669)

- Hutton, James. Theory of the Earth, 1795

- Lyell, Charles. Principles of Geology, 1830