Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Three-dimensional space

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2016) |

In geometry, a three-dimensional space (3D space, 3-space or, rarely, tri-dimensional space) is a mathematical space in which three values (coordinates) are required to determine the position of a point. Most commonly, it is the three-dimensional Euclidean space, that is, the Euclidean space of dimension three, which models physical space. More general three-dimensional spaces are called 3-manifolds. The term may also refer colloquially to a subset of space, a three-dimensional region (or 3D domain),[1] a solid figure.

Technically, a tuple of n numbers can be understood as the Cartesian coordinates of a location in a n-dimensional Euclidean space. The set of these n-tuples is commonly denoted and can be identified to the pair formed by a n-dimensional Euclidean space and a Cartesian coordinate system. When n = 3, this space is called the three-dimensional Euclidean space (or simply "Euclidean space" when the context is clear).[2] In classical physics, it serves as a model of the physical universe, in which all known matter exists. When relativity theory is considered, it can be considered a local subspace of space-time.[3] While this space remains the most compelling and useful way to model the world as it is experienced,[4] it is only one example of a 3-manifold. In this classical example, when the three values refer to measurements in different directions (coordinates), any three directions can be chosen, provided that these directions do not lie in the same plane. Furthermore, if these directions are pairwise perpendicular, the three values are often labeled by the terms width/breadth, height/depth, and length.

History

[edit]Books XI to XIII of Euclid's Elements dealt with three-dimensional geometry. Book XI develops notions of perpendicularity and parallelism of lines and planes, and defines solids including parallelepipeds, pyramids, prisms, spheres, octahedra, icosahedra and dodecahedra. Book XII develops notions of similarity of solids. Book XIII describes the construction of the five regular Platonic solids in a sphere.

In the 17th century, three-dimensional space was described with Cartesian coordinates, with the advent of analytic geometry developed by René Descartes in his work La Géométrie and Pierre de Fermat in the manuscript Ad locos planos et solidos isagoge (Introduction to Plane and Solid Loci), which was unpublished during Fermat's lifetime. However, only Fermat's work dealt with three-dimensional space.

In the 19th century, developments of the geometry of three-dimensional space came with William Rowan Hamilton's development of the quaternions. In fact, it was Hamilton who coined the terms scalar and vector, and they were first defined within his geometric framework for quaternions. Three dimensional space could then be described by quaternions which had vanishing scalar component, that is, . While not explicitly studied by Hamilton, this indirectly introduced notions of basis, here given by the quaternion elements , as well as the dot product and cross product, which correspond to (the negative of) the scalar part and the vector part of the product of two vector quaternions.

It was not until Josiah Willard Gibbs that these two products were identified in their own right, and the modern notation for the dot and cross product were introduced in his classroom teaching notes, found also in the 1901 textbook Vector Analysis written by Edwin Bidwell Wilson based on Gibbs' lectures.

Also during the 19th century came developments in the abstract formalism of vector spaces, with the work of Hermann Grassmann and Giuseppe Peano, the latter of whom first gave the modern definition of vector spaces as an algebraic structure.

In Euclidean geometry

[edit]Coordinate systems

[edit]| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

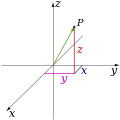

In mathematics, analytic geometry (also called Cartesian geometry) describes every point in three-dimensional space by means of three coordinates. Three coordinate axes are given, each perpendicular to the other two at the origin, the point at which they cross. They are usually labeled x, y, and z. Relative to these axes, the position of any point in three-dimensional space is given by an ordered triple of real numbers, each number giving the distance of that point from the origin measured along the given axis, which is equal to the distance of that point from the plane determined by the other two axes.[5]

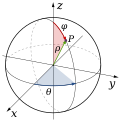

Other popular methods of describing the location of a point in three-dimensional space include cylindrical coordinates and spherical coordinates, though there are an infinite number of possible methods. For more, see Euclidean space.

Below are images of the above-mentioned systems.

Lines and planes

[edit]Two distinct points always determine a (straight) line. Three distinct points are either collinear or determine a unique plane. On the other hand, four distinct points can either be collinear, coplanar, or determine the entire space.

Two distinct lines can either intersect, be parallel or be skew. Two parallel lines, or two intersecting lines, lie in a unique plane, so skew lines are lines that do not meet and do not lie in a common plane.

Two distinct planes can either meet in a common line or are parallel (i.e., do not meet). Three distinct planes, no pair of which are parallel, can either meet in a common line, meet in a unique common point, or have no point in common. In the last case, the three lines of intersection of each pair of planes are mutually parallel.

A line can lie in a given plane, intersect that plane in a unique point, or be parallel to the plane. In the last case, there will be lines in the plane that are parallel to the given line.

A hyperplane is a subspace of one dimension less than the dimension of the full space. The hyperplanes of a three-dimensional space are the two-dimensional subspaces, that is, the planes. In terms of Cartesian coordinates, the points of a hyperplane satisfy a single linear equation, so planes in this 3-space are described by linear equations. A line can be described by a pair of independent linear equations—each representing a plane having this line as a common intersection.

Varignon's theorem states that the midpoints of any quadrilateral in form a parallelogram, and hence are coplanar.

Spheres and balls

[edit]

A sphere in 3-space (also called a 2-sphere because it is a 2-dimensional object) consists of the set of all points in 3-space at a fixed distance r from a central point P. The solid enclosed by the sphere is called a ball (or, more precisely a 3-ball).

The volume of the ball is given by

and the surface area of the sphere is Another type of sphere arises from a 4-ball, whose three-dimensional surface is the 3-sphere: points equidistant to the origin of the euclidean space R4. If a point has coordinates, P(x, y, z, w), then x2 + y2 + z2 + w2 = 1 characterizes those points on the unit 3-sphere centered at the origin.

This 3-sphere is an example of a 3-manifold: a space which is 'looks locally' like 3-D space. In precise topological terms, each point of the 3-sphere has a neighborhood which is homeomorphic to an open subset of 3-D space.

Polytopes

[edit]In three dimensions, there are nine regular polytopes: the five convex Platonic solids and the four nonconvex Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra.

| Class | Platonic solids | Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Td | Oh | Ih | ||||||

| Coxeter group | A3, [3,3] | B3, [4,3] | H3, [5,3] | ||||||

| Order | 24 | 48 | 120 | ||||||

| Regular polyhedron |

{3,3} |

{4,3} |

{3,4} |

{5,3} |

{3,5} |

{5/2,5} |

{5,5/2} |

{5/2,3} |

{3,5/2} |

Surfaces of revolution

[edit]A surface generated by revolving a plane curve about a fixed line in its plane as an axis is called a surface of revolution. The plane curve is called the generatrix of the surface. A section of the surface, made by intersecting the surface with a plane that is perpendicular (orthogonal) to the axis, is a circle.

Simple examples occur when the generatrix is a line. If the generatrix line intersects the axis line, the surface of revolution is a right circular cone with vertex (apex) the point of intersection. However, if the generatrix and axis are parallel, then the surface of revolution is a circular cylinder.

Quadric surfaces

[edit]In analogy with the conic sections, the set of points whose Cartesian coordinates satisfy the general equation of the second degree, namely, where A, B, C, F, G, H, J, K, L and M are real numbers and not all of A, B, C, F, G and H are zero, is called a quadric surface.[6]

There are six types of non-degenerate quadric surfaces:

- Ellipsoid

- Hyperboloid of one sheet

- Hyperboloid of two sheets

- Elliptic cone

- Elliptic paraboloid

- Hyperbolic paraboloid

The degenerate quadric surfaces are the empty set, a single point, a single line, a single plane, a pair of planes or a quadratic cylinder (a surface consisting of a non-degenerate conic section in a plane π and all the lines of R3 through that conic that are normal to π).[6] Elliptic cones are sometimes considered to be degenerate quadric surfaces as well.

Both the hyperboloid of one sheet and the hyperbolic paraboloid are ruled surfaces, meaning that they can be made up from a family of straight lines. In fact, each has two families of generating lines, the members of each family are disjoint and each member one family intersects, with just one exception, every member of the other family.[7] Each family is called a regulus.

In linear algebra

[edit]Another way of viewing three-dimensional space is found in linear algebra, where the idea of independence is crucial. Space has three dimensions because the length of a box is independent of its width or breadth. In the technical language of linear algebra, space is three-dimensional because every point in space can be described by a linear combination of three independent vectors.

Dot product, angle, and length

[edit]A vector can be pictured as an arrow. The vector's magnitude is its length, and its direction is the direction the arrow points. A vector in can be represented by an ordered triple of real numbers. These numbers are called the components of the vector.

The dot product of two vectors A = [A1, A2, A3] and B = [B1, B2, B3] is defined as:[8]

The magnitude of a vector A is denoted by ||A||. The dot product of a vector A = [A1, A2, A3] with itself is

which gives

the formula for the Euclidean length of the vector.

Without reference to the components of the vectors, the dot product of two non-zero Euclidean vectors A and B is given by[9]

where θ is the angle between A and B.

Cross product

[edit]The cross product or vector product is a binary operation on two vectors in three-dimensional space and is denoted by the symbol ×. The cross product A × B of the vectors A and B is a vector that is perpendicular to both and therefore normal to the plane containing them. It has many applications in mathematics, physics, and engineering.

In function language, the cross product is a function .

The components of the cross product are , and can also be written in components, using Einstein summation convention as where is the Levi-Civita symbol. It has the property that .

Its magnitude is related to the angle between and by the identity

The space and product form an algebra over a field, which is not commutative nor associative, but is a Lie algebra with the cross product being the Lie bracket. Specifically, the space together with the product, is isomorphic to the Lie algebra of three-dimensional rotations, denoted . In order to satisfy the axioms of a Lie algebra, instead of associativity the cross product satisfies the Jacobi identity. For any three vectors and

One can in n dimensions take the product of n − 1 vectors to produce a vector perpendicular to all of them. But if the product is limited to non-trivial binary products with vector results, it exists only in three and seven dimensions.[10]

Abstract description

[edit]It can be useful to describe three-dimensional space as a three-dimensional vector space over the real numbers. This differs from in a subtle way. By definition, there exists a basis for . This corresponds to an isomorphism between and : the construction for the isomorphism is found here. However, there is no 'preferred' or 'canonical basis' for .

On the other hand, there is a preferred basis for , which is due to its description as a Cartesian product of copies of , that is, . This allows the definition of canonical projections, , where . For example, . This then allows the definition of the standard basis defined by where is the Kronecker delta. Written out in full, the standard basis is

Therefore can be viewed as the abstract vector space, together with the additional structure of a choice of basis. Conversely, can be obtained by starting with and 'forgetting' the Cartesian product structure, or equivalently the standard choice of basis.

As opposed to a general vector space , the space is sometimes referred to as a coordinate space.[11]

Physically, it is conceptually desirable to use the abstract formalism in order to assume as little structure as possible if it is not given by the parameters of a particular problem. For example, in a problem with rotational symmetry, working with the more concrete description of three-dimensional space assumes a choice of basis, corresponding to a set of axes. But in rotational symmetry, there is no reason why one set of axes is preferred to say, the same set of axes which has been rotated arbitrarily. Stated another way, a preferred choice of axes breaks the rotational symmetry of physical space.

Computationally, it is necessary to work with the more concrete description in order to do concrete computations.

Affine description

[edit]A more abstract description still is to model physical space as a three-dimensional affine space over the real numbers. This is unique up to affine isomorphism. It is sometimes referred to as three-dimensional Euclidean space. Just as the vector space description came from 'forgetting the preferred basis' of , the affine space description comes from 'forgetting the origin' of the vector space. Euclidean spaces are sometimes called Euclidean affine spaces for distinguishing them from Euclidean vector spaces.[12]

This is physically appealing as it makes the translation invariance of physical space manifest. A preferred origin breaks the translational invariance.

Inner product space

[edit]The above discussion does not involve the dot product. The dot product is an example of an inner product. Physical space can be modelled as a vector space which additionally has the structure of an inner product. The inner product defines notions of length and angle (and therefore in particular the notion of orthogonality). For any inner product, there exist bases under which the inner product agrees with the dot product, but again, there are many different possible bases, none of which are preferred. They differ from one another by a rotation, an element of the group of rotations SO(3).

In calculus

[edit]Gradient, divergence and curl

[edit]In a rectangular coordinate system, the gradient of a (differentiable) function is given by

and in index notation is written

The divergence of a (differentiable) vector field F = U i + V j + W k, that is, a function , is equal to the scalar-valued function:

In index notation, with Einstein summation convention this is

Expanded in Cartesian coordinates (see Del in cylindrical and spherical coordinates for spherical and cylindrical coordinate representations), the curl ∇ × F is, for F composed of [Fx, Fy, Fz]:

where i, j, and k are the unit vectors for the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively. This expands as follows:[13]

In index notation, with Einstein summation convention this is where is the totally antisymmetric symbol, the Levi-Civita symbol.

Line, surface, and volume integrals

[edit]For some scalar field f : U ⊆ Rn → R, the line integral along a piecewise smooth curve C ⊂ U is defined as

where r: [a, b] → C is an arbitrary bijective parametrization of the curve C such that r(a) and r(b) give the endpoints of C and .

For a vector field F : U ⊆ Rn → Rn, the line integral along a piecewise smooth curve C ⊂ U, in the direction of r, is defined as

where · is the dot product and r: [a, b] → C is a bijective parametrization of the curve C such that r(a) and r(b) give the endpoints of C.

A surface integral is a generalization of multiple integrals to integration over surfaces. It can be thought of as the double integral analog of the line integral. To find an explicit formula for the surface integral, we need to parameterize the surface of interest, S, by considering a system of curvilinear coordinates on S, like the latitude and longitude on a sphere. Let such a parameterization be x(s, t), where (s, t) varies in some region T in the plane. Then, the surface integral is given by

where the expression between bars on the right-hand side is the magnitude of the cross product of the partial derivatives of x(s, t), and is known as the surface element. Given a vector field v on S, that is a function that assigns to each x in S a vector v(x), the surface integral can be defined component-wise according to the definition of the surface integral of a scalar field; the result is a vector.

A volume integral is an integral over a three-dimensional domain or region. When the integrand is trivial (unity), the volume integral is simply the region's volume.[14][1] It can also mean a triple integral within a region D in R3 of a function and is usually written as:

Fundamental theorem of line integrals

[edit]The fundamental theorem of line integrals, says that a line integral through a gradient field can be evaluated by evaluating the original scalar field at the endpoints of the curve.

Let . Then

Stokes' theorem

[edit]Stokes' theorem relates the surface integral of the curl of a vector field F over a surface Σ in Euclidean three-space to the line integral of the vector field over its boundary ∂Σ:

Divergence theorem

[edit]Suppose V is a subset of (in the case of n = 3, V represents a volume in 3D space) which is compact and has a piecewise smooth boundary S (also indicated with ∂V = S). If F is a continuously differentiable vector field defined on a neighborhood of V, then the divergence theorem says:[15]

The left side is a volume integral over the volume V, the right side is the surface integral over the boundary of the volume V. The closed manifold ∂V is quite generally the boundary of V oriented by outward-pointing normals, and n is the outward pointing unit normal field of the boundary ∂V. (dS may be used as a shorthand for ndS.)

In topology

[edit]

Three-dimensional space has a number of topological properties that distinguish it from spaces of other dimension numbers. For example, at least three dimensions are required to tie a knot in a piece of string.[16]

In differential geometry the generic three-dimensional spaces are 3-manifolds, which locally resemble .

In finite geometry

[edit]Many ideas of dimension can be tested with finite geometry. The simplest instance is PG(3,2), which has Fano planes as its 2-dimensional subspaces. It is an instance of Galois geometry, a study of projective geometry using finite fields. Thus, for any Galois field GF(q), there is a projective space PG(3,q) of three dimensions. For example, any three skew lines in PG(3,q) are contained in exactly one regulus.[17]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "IEC 60050 — Details for IEV number 102-04-39: "three-dimensional domain"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ "Euclidean space - Encyclopedia of Mathematics". encyclopediaofmath.org. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ "Details for IEV number 113-01-02: "space"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ "Euclidean space | geometry". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- ^ Hughes-Hallett, Deborah; McCallum, William G.; Gleason, Andrew M. (2013). Calculus : Single and Multivariable (6 ed.). John wiley. ISBN 978-0470-88861-2.

- ^ a b Brannan, Esplen & Gray 1999, pp. 34–35

- ^ Brannan, Esplen & Gray 1999, pp. 41–42

- ^ Anton 1994, p. 133

- ^ Anton 1994, p. 131

- ^ Massey, WS (1983). "Cross products of vectors in higher dimensional Euclidean spaces". The American Mathematical Monthly. 90 (10): 697–701. doi:10.2307/2323537. JSTOR 2323537.

If one requires only three basic properties of the cross product ... it turns out that a cross product of vectors exists only in 3-dimensional and 7-dimensional Euclidean space.

- ^ Lang 1987, ch. I.1

- ^ Berger 1987, Chapter 9.

- ^ Arfken, p. 43.

- ^ "IEC 60050 — Details for IEV number 102-04-40: "volume"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ M. R. Spiegel; S. Lipschutz; D. Spellman (2009). Vector Analysis. Schaum's Outlines (2nd ed.). US: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7.

- ^ Rolfsen, Dale (1976). Knots and Links. Berkeley, California: Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-16-0.

- ^ Albrecht Beutelspacher & Ute Rosenbaum (1998) Projective Geometry, page 72, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-48277-1

References

[edit]- Anton, Howard (1994), Elementary Linear Algebra (7th ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-58742-2

- Arfken, George B. and Hans J. Weber. Mathematical Methods For Physicists, Academic Press; 6 edition (June 21, 2005). ISBN 978-0-12-059876-2.

- Berger, Marcel (1987), Geometry I, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 3-540-11658-3

- Brannan, David A.; Esplen, Matthew F.; Gray, Jeremy J. (1999), Geometry, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-59787-6

- Lang, Serge (1987), Linear algebra, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (3rd ed.), Springer, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-1949-9, ISBN 978-1-4757-1949-9

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of three-dimensional at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of three-dimensional at Wiktionary- Weisstein, Eric W. "Four-Dimensional Geometry". MathWorld.

- Elementary Linear Algebra - Chapter 8: Three-dimensional Geometry Keith Matthews from University of Queensland, 1991

Three-dimensional space

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient and medieval perspectives

In ancient Greek philosophy, space was conceptualized not as an abstract void but as an integral aspect of the physical world, serving as a container for material bodies. Aristotle, in his Physics (Book IV), defined place (topos) as the innermost boundary of the containing body, emphasizing that space is relational and dependent on the presence of bodies rather than an independent entity.[10] This view portrayed three-dimensional space as a plenum filled with substances, where extension arises from the arrangement of matter, influencing later understandings of spatial containment without invoking empty voids.[11] Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BCE) further shaped early intuitions of three-dimensional geometry through synthetic methods, describing solids such as polyhedra and spheres via axioms and postulates without coordinate systems or algebraic formalism. Books XI–XIII of the Elements establish properties of planes and volumes intuitively, treating space as a continuous medium for geometric constructions observable in everyday objects like buildings and celestial bodies.[12] These works provided a foundational framework for visualizing spatial relations, prioritizing empirical deduction over measurement.[13] Contributions from Indian and Islamic scholars expanded observational approaches to three-dimensional space, particularly through astronomy. Aryabhata, in his Aryabhatiya (499 CE), developed spherical trigonometry for modeling celestial motions, treating the Earth and heavens as embedded in a three-dimensional spherical framework to compute planetary positions and eclipses.[14] In the 11th century, Al-Biruni advanced geodetic measurements by determining the Earth's radius using trigonometric observations from mountain elevations, confirming its sphericity and curvature with an accuracy close to modern values, thus refining conceptions of global spatial extent.[15] During the medieval European period, scholastic thinkers synthesized these ideas with Christian theology. Thomas Aquinas, drawing on Aristotle in works like Summa Theologica, integrated the notion of space as a bounded container into a cosmological hierarchy where the finite, three-dimensional universe reflects divine order, with heavenly spheres encompassing earthly bodies in a geocentric model.[16] This reconciliation portrayed space as a created medium, harmonious with faith, bridging philosophical inquiry and religious worldview.[17] A pivotal development bridging medieval and Renaissance views occurred in the 15th century through artistic innovations, exemplified by Filippo Brunelleschi's experiments in Florence around 1420. Using mirrors and peepholes to project the Baptistery's facade onto a painted panel, Brunelleschi demonstrated linear perspective, enabling two-dimensional representations that mimicked three-dimensional depth and spatial recession, thus enhancing perceptual understanding of volume and distance.[18] These techniques, while artistic, laid groundwork for later mathematical formalizations of space.Modern mathematical development

The modern mathematical development of three-dimensional space began in the 17th century with René Descartes' introduction of Cartesian coordinates in his 1637 work La Géométrie, which allowed for the algebraic representation of points, lines, and surfaces in 3D space through ordered triples of numbers, transforming geometry into an analytic discipline.[19] This innovation enabled the precise description of spatial relationships using equations, bridging algebra and geometry and laying the foundation for subsequent advancements in vector analysis and coordinate-based modeling.[19] In the 18th century, Leonhard Euler advanced the study of polyhedra and space-filling structures, culminating in his 1752 formulation of the relation for convex polyhedra, where denotes vertices, edges, and faces, providing a topological invariant that characterizes the connectivity of 3D polyhedral forms.[20] Euler's explorations also included analyses of regular polyhedra and tessellations, contributing to understandings of how shapes fill 3D space without gaps or overlaps.[21] The 19th century saw significant progress in projective and differential geometry relevant to 3D space. Carl Friedrich Gauss's 1827 Theorema Egregium demonstrated that the Gaussian curvature of a surface embedded in 3D space is an intrinsic property, independent of its embedding, which was later generalized to surfaces in higher dimensions. August Ferdinand Möbius, in his 1827 Der barycentrische Calcül, introduced barycentric coordinates, facilitating projective treatments of points and figures in 3D projective space by expressing positions as weighted combinations relative to reference points.[22] Julius Plücker extended projective geometry to lines in 3D space through his line coordinates, introduced in works from the 1840s and elaborated in 1868's Theorie der Flächen, representing lines via six homogeneous coordinates and enabling algebraic studies of line complexes. Bernhard Riemann's 1854 habilitation lecture Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen developed the framework of Riemannian geometry, describing curved 3D spaces via metrics on manifolds and providing the mathematical basis for non-Euclidean geometries.[23] Entering the 20th century, Henri Poincaré's foundational work in topology, particularly his 1895 Analysis Situs and subsequent papers, analyzed 3D manifolds as abstract spaces, introducing concepts like fundamental groups to classify their connectivity and homology, which distinguished simply connected spaces and influenced the study of 3D topological structures.Euclidean geometry

Coordinate systems

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, the Cartesian coordinate system provides a standard framework for locating points using three mutually perpendicular axes intersecting at the origin. A point is represented by an ordered triple , where , , and denote the signed distances from the origin along the respective axes, typically oriented as the x-axis (horizontal), y-axis (depth), and z-axis (vertical). The assignment of terms such as depth (for horizontal extension) or height (for vertical) is conventional and varies by context; these are labels for the same three perpendicular axes rather than distinct dimensions. This system, introduced by René Descartes in his 1637 work La Géométrie, extends the two-dimensional plane to allow precise positioning in space.[24][25] The distance between two points and in this system is given by the Euclidean metric: which generalizes the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions.[26] Alternative coordinate systems, such as cylindrical and spherical, simplify representations when symmetry about an axis or radial structure is present. Cylindrical coordinates describe a point by its radial distance from the z-axis in the xy-plane, the azimuthal angle (measured from the positive x-axis), and the height along the z-axis. The conversion to Cartesian coordinates is: For volume integrals, the Jacobian determinant yields the volume element , accounting for the scaling in the radial direction.[27][28] Spherical coordinates use the radial distance from the origin, the polar angle (from the positive z-axis, ), and the azimuthal angle (from the positive x-axis in the xy-plane, ). The conversion formulas are: This system is particularly useful for problems exhibiting radial symmetry, such as those involving spheres or isotropic fields.[29] Coordinate transformations, such as rotations, preserve distances and angles in Euclidean space and are represented by orthogonal matrices with determinant 1. For a counterclockwise rotation by angle around the z-axis, the transformation matrix applied to a point's Cartesian coordinates is: Such matrices facilitate changing the orientation of axes or objects while maintaining the underlying geometry.[30]Lines, planes, and distances

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a line can be defined using parametric equations that describe its position as a function of a parameter . The parametric form passing through a point with direction vector is given by where ./01%3A_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.05%3A_Equations_of_Lines_in_3d) The direction vector indicates the orientation and scaling of the line, and any scalar multiple of it yields an equivalent representation.[31] To determine if two lines intersect, their parametric equations are set equal to solve for parameters and . For lines and , intersection occurs if there exist scalars and such that , which rearranges to ; a unique solution implies intersection at that point, while no solution indicates skew or parallel non-intersecting lines.[31] If the direction vectors are parallel (one is a scalar multiple of the other) and the lines do not coincide, they are parallel and do not intersect unless the vector between points on each lies in the span of the direction.[32] A plane in three-dimensional space is defined by the general equation , where is the normal vector perpendicular to the plane.[33] This normal vector determines the plane's orientation, and the equation can be derived from a point on the plane and the normal via ./01%3A_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.05%3A_Equations_of_Lines_in_3d) The distance from a point to the plane is the length of the perpendicular from the point to the plane, calculated as This formula arises from projecting the vector from a point on the plane to onto the unit normal vector.[34][35] The angle between two lines is found using the cosine of the angle between their direction vectors and , given by , where the acute angle is considered.[36] Similarly, the angle between two planes is the angle between their normal vectors and , with .[36] For the angle between a line with direction and a plane with normal , the setup involves the complement of the angle between and , using for the acute angle ./01%3A_Vectors_and_Geometry_in_Two_and_Three_Dimensions/1.05%3A_Equations_of_Lines_in_3d) For two skew lines (non-intersecting and non-parallel) with parametric forms and , the shortest distance is the length of the common perpendicular, given by This expression uses the cross product to find the direction perpendicular to both lines, and the scalar triple product to project the vector between points onto that direction.[37]Spheres, balls, and polytopes

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, a sphere is defined as the set of all points equidistant from a fixed center point, with that distance being the radius . Using Cartesian coordinates, the equation of a sphere centered at is given by This locus represents the surface of the sphere.[38] The surface area of the sphere is , derived by considering the sphere as the limit of polyhedral approximations or through integration in spherical coordinates.[39] The volume enclosed by the sphere, known as the ball of radius , is , which can be obtained via triple integration over the region or by the method of Cavalieri's principle.[39] A ball in three dimensions is the solid object comprising the sphere and its interior, defined as the set of points whose distance from the center is at most .[40] On the sphere's surface, great circles—formed by the intersection of the sphere with any plane passing through its center—represent the geodesics, or shortest paths connecting two points along the surface. These curves are the three-dimensional analogues of straight lines and have constant curvature equal to that of the sphere.[41] Convex polytopes in three dimensions are polyhedra, bounded by flat polygonal faces, straight edges, and vertices. The regular convex polyhedra, called Platonic solids, are classified into five types: the tetrahedron (4 triangular faces), cube (6 square faces), octahedron (8 triangular faces), dodecahedron (12 pentagonal faces), and icosahedron (20 triangular faces); each has congruent regular polygonal faces and the same number meeting at every vertex.[42] For any convex polyhedron that is topologically equivalent to a sphere, the Euler characteristic satisfies , where , , and denote the numbers of vertices, edges, and faces, respectively; this relation holds due to the polyhedron's spherical topology and can be verified inductively by decomposition.[43] Some convex polyhedra admit space-filling tessellations, partitioning three-dimensional space without gaps or overlaps. The cubic honeycomb, consisting of identical cubes arranged in a lattice, is a prominent example, with each cube sharing faces with six neighbors.[44] Volumes of Platonic solids provide concrete measures of their spatial extent; for instance, a cube of side length has volume , while a regular tetrahedron of side length has volume , computed by dividing the tetrahedron into pyramids or using vector cross products for the enclosed space.[45]Quadric surfaces and surfaces of revolution

Quadric surfaces in three-dimensional Euclidean space are defined by second-degree polynomial equations in the variables , , and . The general equation takes the form where the coefficients determine the specific type of surface through the eigenvalues of the associated quadratic form or by completing the square and translating coordinates.[46] These surfaces are classified into non-degenerate types—ellipsoids, hyperboloids of one or two sheets, elliptic and hyperbolic paraboloids—and degenerate cases such as cones, cylinders, and pairs of planes, based on the signs and ranks of the quadratic terms after canonical reduction.[47] Among these, the ellipsoid represents a bounded, closed surface analogous to an ellipse stretched in three dimensions, with the standard equation where , , and are positive semi-axes lengths; when , it reduces to a sphere.[47] The hyperbolic paraboloid, a ruled surface known for its saddle-like shape, features hyperbolic cross-sections and is given by in canonical form, exhibiting both positive and negative curvatures along principal directions.[48] Surfaces of revolution arise by rotating a curve in a plane around an axis lying in that plane but not intersecting the curve, producing rotationally symmetric surfaces in three dimensions.[49] For instance, revolving a semicircle about its diameter yields a sphere, while rotating a circle offset from the axis generates a torus, whose implicit equation is with denoting the major and minor radii, respectively.[50] Pappus's centroid theorem provides a method to compute areas and volumes of such surfaces without integration: the lateral surface area equals the arc length of the generating curve times the circumference described by its centroid (i.e., times the centroid's distance to the axis), and the enclosed volume equals the area under the curve times the same circumferential distance.[49] This theorem, attributed to Pappus of Alexandria in the 4th century CE, relies on the centroid's definition as the average position weighted by arc length or area.[51]Linear algebra

Vectors, dot product, and norms

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, vectors are commonly represented as ordered triples of real numbers, , where , , and are the components along the respective Cartesian axes.[25] This representation corresponds to the displacement from the origin to a point in . Vector addition is performed component-wise: , which geometrically corresponds to the parallelogram rule.[52] Scalar multiplication scales the vector by a real number , yielding , altering its magnitude while preserving direction (or reversing it if ).[53] The dot product of two vectors and in three dimensions is defined algebraically as .[54] Geometrically, it equals , where is the angle between the vectors and denotes the Euclidean norm; this relation links the algebraic form to the spatial orientation.[55] Two nonzero vectors are orthogonal if their dot product is zero, as implies .[56] The Euclidean norm, or length, of a vector is given by , providing a measure of magnitude invariant under rotations.[57] A unit vector, with norm 1, is obtained by normalizing: for .[58] The vector projection of onto (nonzero) is , representing the component of parallel to .[59] These concepts find applications in determining the angle between vectors via , essential for geometric computations.[60] In physics, the dot product computes work as , where is force and is displacement, capturing only the component of force along the path.[61]Cross product and orientations

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, the cross product of two vectors and is a vector defined by the determinant-like formula /01:_Vectors_in_Euclidean_Space/1.04:_Cross_Product) This operation yields a vector perpendicular to both and , with magnitude , where is the angle between them; geometrically, this magnitude equals the area of the parallelogram formed by and as adjacent sides./01:_Vectors_in_Euclidean_Space/1.04:_Cross_Product) Key properties of the cross product include anticommutativity, , and orthogonality to its input vectors, and ./01:_Vectors_in_Euclidean_Space/1.04:_Cross_Product) The direction follows the right-hand rule: aligning the fingers of the right hand with and curling them toward points the thumb in the direction of .[62] These attributes make the cross product useful for determining a normal vector to the plane spanned by and , essential in applications like surface parameterization./01:_Vectors_in_Euclidean_Space/1.04:_Cross_Product) In physics, the cross product computes torque as , where is the position vector from the pivot to the force application point and is the force, yielding a vector whose magnitude is and direction indicates the rotation axis.[63] For volumes, the scalar triple product gives the signed volume of the parallelepiped spanned by , , and , with the absolute value representing the actual volume.[64] The cross product inherently encodes orientations through its handedness, distinguishing chiral (handed) structures in 3D space via the right-hand rule, which selects one of two possible perpendicular directions.[62] This vector-valued binary operation is unique to three dimensions; in higher dimensions, analogous constructions yield higher-rank tensors or subspaces rather than vectors.[65]Abstract vector spaces

In the context of three-dimensional space, the algebraic structure can be abstracted to a finite-dimensional vector space over the real numbers , providing a foundation for linear operations independent of specific geometric embeddings. A vector space over is a set equipped with two operations: vector addition and scalar multiplication , satisfying the following axioms: for all and ,- Associativity of addition: ,

- Commutativity of addition: ,

- Existence of zero vector: there exists such that ,

- Additive inverses: for each , there exists such that ,

- Distributivity over vector addition: ,

- Distributivity over scalar addition: ,

- Compatibility: ,

- Identity for scalar multiplication: .[66]

Calculus

Vector calculus operators

In three-dimensional Euclidean space, vector calculus operators such as the gradient, divergence, curl, and Laplacian provide essential tools for analyzing scalar and vector fields, capturing local properties like rates of change, sources, rotations, and diffusion.[71] These operators, collectively denoted using the del (or nabla) symbol ∇, are defined primarily in Cartesian coordinates but extend to other systems like cylindrical and spherical coordinates, facilitating computations in diverse geometric contexts.[71] The gradient of a scalar field , denoted , is a vector field that points in the direction of the steepest ascent of and whose magnitude equals the rate of that ascent.[72] In Cartesian coordinates, it is expressed as This operator transforms a scalar into a vector, highlighting directional derivatives aligned with the field's increase.[72] The divergence of a vector field , denoted , quantifies the net flux emanating from a point, positive for sources and negative for sinks, representing the rate at which the field's density exits a local volume.[73] In Cartesian coordinates, it takes the form This scalar operator measures expansion or contraction within the field.[73] The curl of a vector field , denoted , is a vector field whose magnitude indicates the maximum rotation (circulation per unit area) at a point and whose direction aligns with the axis of that rotation, following the right-hand rule.[74] A field is irrotational if . In Cartesian coordinates, it is given by This antisymmetric operator detects local vorticity.[74] The Laplacian of a scalar field , denoted or , is the divergence of the gradient, , and serves as a measure of the field's variation or diffusivity, appearing in equations for heat, waves, and potentials.[75] Functions satisfying are harmonic, exhibiting mean-value properties over spheres. In Cartesian coordinates, This second-order scalar operator is fundamental in many physical laws.[75] These operators adapt to curvilinear coordinates for problems with symmetry. The table below summarizes their expressions in Cartesian, cylindrical , and spherical coordinates, where scale factors account for the geometry.[76][77]| Operator | Cartesian | Cylindrical | Spherical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient | |||

| Divergence | |||

| Curl | |||

| Laplacian |

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {A} \times \mathbf {B} =[A_{2}B_{3}-B_{2}A_{3},A_{3}B_{1}-B_{3}A_{1},A_{1}B_{2}-B_{1}A_{2}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a586a3bca8700c41c66803055590a4ff5fd15326)

![{\displaystyle \varphi \left(\mathbf {q} \right)-\varphi \left(\mathbf {p} \right)=\int _{\gamma [\mathbf {p} ,\,\mathbf {q} ]}\nabla \varphi (\mathbf {r} )\cdot d\mathbf {r} .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b27cdd0377931a70cbb0635e37781a42e7fe33f9)