Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cycloconverter

View on Wikipedia

A cycloconverter (CCV) or a cycloinverter converts a constant amplitude, constant frequency AC waveform to another AC waveform of a lower frequency by synthesizing the output waveform from segments of the AC supply without an intermediate DC link (Dorf 1993, pp. 2241–2243 and Lander 1993, p. 181). There are two main types of CCVs, circulating current type and blocking mode type, most commercial high power products being of the blocking mode type.[2]

Characteristics

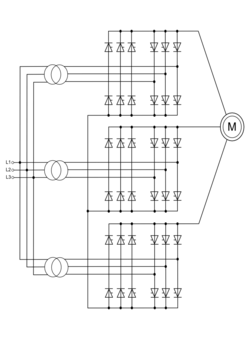

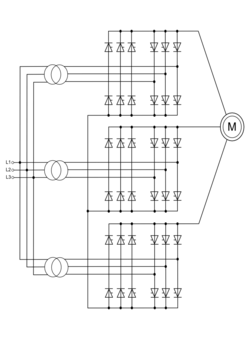

[edit]Whereas phase-controlled semiconductor controlled rectifier devices (SCR) can be used throughout the range of CCVs, low cost, low-power TRIAC-based CCVs are inherently reserved for resistive load applications. The amplitude and frequency of converters' output voltage are both variable. The output to input frequency ratio of a three-phase CCV must be less than about one-third for circulating current mode CCVs or one-half for blocking mode CCVs.(Lander 1993, p. 188)[3] Output waveform quality improves as the pulse number of switching-device bridges in phase-shifted configuration increases in CCV's input. In general, CCVs can be with 1-phase/1-phase, 3-phase/1-phase and 3-phase/3-phase input/output configurations, most applications however being 3-phase/3-phase.[1]

Applications

[edit]The competitive power rating span of standardized CCVs ranges from few megawatts up to many tens of megawatts. CCVs are used for driving mine hoists, rolling mill main motors,[4] ball mills for ore processing, cement kilns, ship propulsion systems,[5] slip power recovery wound-rotor induction motors (i.e., Scherbius drives) and aircraft 400 Hz power generation.[6] The variable-frequency output of a cycloconverter can be reduced essentially to zero. This means that very large motors can be started on full load at very slow revolutions, and brought gradually up to full speed. This is invaluable with, for example, ball mills, allowing starting with a full load rather than the alternative of having to start the mill with an empty barrel then progressively load it to full capacity. A fully loaded "hard start" for such equipment would essentially be applying full power to a stalled motor. Variable speed and reversing are essential to processes such as hot-rolling steel mills. Previously, SCR-controlled DC motors were used, needing regular brush/commutator servicing and delivering lower efficiency. Cycloconverter-driven synchronous motors need less maintenance and give greater reliability and efficiency. Single-phase bridge CCVs have also been used extensively in electric traction applications to for example produce 25 Hz power in the U.S. and 16 2/3 Hz power in Europe.[7][8]

Whereas phase-controlled converters including CCVs are gradually being replaced by faster PWM self-controlled converters based on IGBT, GTO, IGCT and other switching devices, these older classical converters are still used at the higher end of the power rating range of these applications.[3]

Harmonics

[edit]CCV operation creates current and voltage harmonics on the CCV's input and output. AC line harmonics are created on CCV's input accordance to the equation,

- fh = f1 (kq±1) ± 6nfo,[9]

where

- fh = harmonic frequency imposed on the AC line

- k and n = integers

- q = pulse number (6, 12 . . .)

- fo = output frequency of the CCV

- Equation's 1st term represents the pulse number converter harmonic components starting with six-pulse configuration

- Equation's 2nd term denotes the converter's sideband characteristic frequencies including associated interharmonics and subharmonics.

References

[edit]- In-line references

- ^ a b Bose, Bimal K. (2006). Power Electronics and Motor Drives : Advances and Trends. Amsterdam: Academic. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-12-088405-6.

- ^ Klug, Dieter-Rolf; Klaassen, Norbert (2005). "High Power Medium Voltage Drives - Innovations, Portfolio, Trends". European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications. p. 5. doi:10.1109/EPE.2005.219669.

- ^ a b Bose (2006), p. 153

- ^ Watzmann, Marcus Watzmann; Raskowetz, Steffen (Sep–Oct 1996). "Chinese rolling mill for extra high grade aluminium strip" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2014. Retrieved Aug 5, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pakaste, Risto; et al. (Feb 1999). "Experience with Azipod propulsion systems on board marine vessels" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bose (2006), p. 119

- ^ Heydt, G.T.; Chu, R.F. (Apr 2005). "The power quality impact of cycloconverter control strategies". IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery. 20 (2): 1711–1718. doi:10.1109/tpwrd.2004.834350. S2CID 7595032.

- ^ ACS 6000c. "Cycloconverter application for high performance speed and torque control of 1 to 27 MW synchronous motors" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ IEEE Std 519 (1992). IEEE Recommended Practices and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electrical Power Systems. IEEE. p. 25. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.1993.114370. ISBN 978-0-7381-0915-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- General references

- Dorf, Richard C., ed. (1993), The Electrical Engineering Handbook, Boca Raton: CRC Press, Bibcode:1993eeh..book.....D, ISBN 0-8493-0185-8

- Lander, Cyril W (1993), Power Electronics (3rd ed.), London: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-707714-8

Cycloconverter

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Overview

A cycloconverter is a direct AC-to-AC power converter that alters the frequency and voltage of an input AC waveform to produce an output AC waveform without requiring an intermediate DC link. It achieves this by using thyristors or silicon-controlled rectifiers (SCRs) arranged in converter banks to selectively connect portions of the input AC supply, thereby synthesizing the desired output through phase control and waveform segmentation.[4] The primary purpose of a cycloconverter is to enable frequency conversion for applications demanding variable speed operation, such as AC motor drives, where the output frequency is typically stepped down to less than one-third of the input frequency to ensure smooth waveform generation and minimize harmonics.[5][4] This direct conversion capability is particularly suited to high-power scenarios, including industrial variable speed drives.[4] In a high-level block diagram, the cycloconverter features an input AC source feeding into multiple thyristor-based converter groups—positive and negative for bidirectional operation—that are gated to produce the output AC. Typical configurations include single-phase to single-phase for simpler loads and three-phase to three-phase for balanced high-power systems.[4] Cycloconverters primarily operate in two modes: circulating current mode, which allows simultaneous conduction in positive and negative groups but requires an intergroup reactor to limit currents, and circulating current-free (blocking) mode, where only one group conducts at a time to avoid short circuits and reduce losses, making the latter the preferred modern approach.[4]Historical Development

The concept of the cycloconverter was first proposed in 1922 by Max Meyer and Louis Alan Hazeltine, who described a method to directly convert AC power from one frequency to another by selectively combining segments of the input waveform, though practical implementations were limited by contemporary technology.[6] Early prototypes emerged in the 1930s using mercury-arc valves, primarily for industrial drives such as railway traction systems; in 1931, German railways deployed the first commercial mercury-arc cycloconverters to convert three-phase 50 Hz power to single-phase 16 2/3 Hz for universal locomotives, marking the initial high-power application of the technology.[7] A notable milestone came in 1934 when Ernst F. W. Alexanderson at General Electric developed the first variable-frequency AC drive using a thyratron-based cycloconverter for a 400 hp wound-field synchronous motor, demonstrating frequency control from DC to near line frequency without an intermediate DC link.[7] Post-World War II advancements accelerated in the 1950s and 1960s with the invention of the silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR), also known as the thyristor, which General Electric engineers commercialized in 1957 after initial proposals from Bell Labs in 1950, enabling more reliable and efficient phase-controlled cycloconverters for high-power applications. This shift from gas-filled tubes to solid-state devices facilitated the first practical three-phase cycloconverters for induction motor speed control, with continuous output frequency adjustment up to one-third the input frequency; by the mid-1960s, these were adopted in steel mill drives and other industrial processes requiring variable low-speed operation.[8] GE engineers, including key contributors like Frank W. Gutzwiller, played a pivotal role in thyristor-based designs, leading to patents such as GB1352881A in 1971 for improved cycloconverter control circuits that enhanced output waveform quality and reduced harmonics.[9] The 1970s and 1980s represented the peak of cycloconverter adoption for megawatt-scale systems, particularly in demanding environments like mining and marine propulsion, where direct low-frequency conversion was advantageous for large synchronous machines.[7] In mining, Siemens introduced the first gearless mill drive (GMD) using a cycloconverter in 1980 for a ball mill in Norway, enabling precise speed control of multi-megawatt grinding mills without mechanical gears, a technology that proliferated for ore processing in the 1980s.[10] For marine applications, the 1986 launch of the Finnish icebreaker Otso featured twin 7.5 MW synchronous propulsion motors fed by cycloconverters, representing one of the earliest large-scale implementations for variable-speed ship drives and highlighting the technology's suitability for high-torque, low-speed operations.[11] Innovations like Toshiba's circulating current method in the 1980s further improved power factor control, solidifying cycloconverters' dominance in these sectors until the late 1980s.[7] By the 1990s, cycloconverters began to decline in favor of pulse-width modulated (PWM) voltage-source inverters, which offered superior harmonic performance, higher efficiency, and simpler control for medium-power variable-speed drives, rendering cycloconverters less competitive in many general applications.[7] Multilevel converter topologies, emerging in the 1990s, further accelerated this shift by providing scalable high-voltage solutions without the subharmonic issues inherent in cycloconverters.[7] However, a resurgence occurred in the 2000s for niche high-power, low-frequency needs, such as gearless mill drives exceeding 20 MW and specialized propulsion systems, where the direct AC-AC conversion without a DC link minimized losses and component count in environments demanding robustness over efficiency. Microprocessor-based controls, introduced in the late 1970s and refined through the 2000s, supported this revival by enabling precise firing angle management and harmonic mitigation.[8]Operating Principles

Basic Operation

A cycloconverter operates by directly converting alternating current (AC) from one frequency to another without an intermediate direct current (DC) link, typically achieving step-down frequency conversion where the output frequency is a fraction of the input frequency, such as or lower.[12] The process begins with the input AC waveform at frequency , which is fed into two converter groups: a positive group that selects portions of the positive half-cycles and a negative group that selects portions of the negative half-cycles from the input phases.[12] Thyristors in each group are fired sequentially to conduct for specific periods, typically lasting one full input cycle or a portion thereof, allowing the selection of input half-cycles to synthesize the desired output waveform at frequency .[12] For instance, to produce one output cycle, the positive group might connect three input cycles for the positive half, while the negative group does the same for the negative half, ensuring the output voltage polarity alternates appropriately. The commutation process in a thyristor-based cycloconverter relies primarily on natural commutation, also known as line or phase commutation, where the line voltages of the input AC supply naturally reverse the voltage across the conducting thyristor to turn it off once the current through it reaches zero. This occurs without additional circuitry for forced turn-off, as the thyristors are line-commutated devices that transfer current from one thyristor to the next in the sequence when the incoming line voltage exceeds the outgoing one, typically with a small overlap angle due to source inductance. In basic configurations, this natural process ensures reliable switching between input phases, limiting the output frequency to about one-third of the input to allow sufficient time for commutation without failure.[12] Cycloconverters can operate in two distinct modes: circulating current mode and blocking mode (also called circulating current-free mode). In circulating current mode, both the positive and negative converter groups are enabled simultaneously, allowing current to flow between them through an intergroup reactor that limits the circulating current to a safe level, such as 20-30% of rated current; this results in smoother output voltage waveforms with reduced discontinuities but introduces additional harmonics and higher conduction losses due to continuous thyristor operation.[12] Conversely, in blocking mode, only one converter group (positive or negative) is active at a time, determined by the direction of output current, while the other is blocked; during transitions between groups, the output voltage and current are forced to zero for a short delay period (typically 1-2 milliseconds) to prevent short circuits, leading to more harmonic distortion and waveform notches but eliminating the need for an intergroup reactor and reducing losses.[12] Blocking mode is preferred in high-power applications for its simplicity and lower component count, though it limits the maximum output voltage to about 70-80% of the theoretical value due to the zero periods. Regarding power flow, a standard thyristor-based cycloconverter exhibits bidirectional output power flow, enabling regenerative operation back to the input supply through four-quadrant operation (all combinations of voltage and current polarity).[12] The input side supports bidirectional power handling due to the AC nature of the supply, allowing reactive power exchange with the grid during operation.[12] This configuration makes it suitable for motoring and regenerative braking applications in motor drives.[12]Waveform Synthesis

In a cycloconverter, the output waveform is synthesized by extracting and concatenating short segments from successive cycles of the input AC waveform, enabling the direct generation of a lower-frequency output without an intermediate DC link. This process involves selecting portions of the input voltage during the conduction periods of thyristors in the positive and negative converter groups, effectively stitching together these segments to form the desired output shape. The resulting output is a stepped waveform that approximates the target AC form, with the steps corresponding to the input segments used.[4] The output frequency is determined by the ratio of input cycles to output pulses and is approximately given by , where is the number of pulses (or segments) per output cycle, is the input frequency, and is the number of input cycles contributing to the output cycle. Typically, practical designs limit to suppress low-order harmonics and ensure stable operation. For instance, in a step-down configuration with a 3:1 frequency ratio (), three full input cycles are used to construct one output cycle, with segments selected to follow the sinusoidal envelope.[4] Amplitude control of the synthesized output is achieved by adjusting the conduction angles of the thyristors through variable firing angles , which determines the duration and starting point of each input segment. By progressively varying across segments—often in a sinusoidal pattern relative to the desired output phase—the fundamental output voltage magnitude can be modulated, with the relation providing the average value for a basic case, where is the input RMS voltage. Segment selection further refines amplitude by choosing higher or lower portions of the input waveform, allowing up to 80-90% of the input amplitude at low output frequencies.[4] The output voltage waveform appears as a stepped approximation of a sine wave, where each step represents a controlled segment from the input. In the 3:1 frequency ratio example, the positive half-cycle of the output might use three ascending segments from consecutive input half-cycles (with decreasing to build the peak), followed by three descending segments for the negative half-cycle (with increasing ), resulting in a six-step waveform per output cycle that closely mimics a sine but with inherent stepping and some distortion. Increasing the number of segments per cycle (higher ) smooths the approximation, reducing harmonic content while maintaining the frequency reduction.[4]Configurations and Types

Single-Phase Cycloconverters

Single-phase cycloconverters are AC-to-AC power converters that directly transform a single-phase input at one frequency to a single-phase output at a typically lower frequency, without an intermediate DC link, making them suitable for low-power applications such as speed control of small motors or heating systems.[13] The basic topology employs two full-wave controlled rectifier bridges connected in anti-parallel, where each bridge consists of four thyristors to handle positive and negative half-cycles of the input voltage for bidirectional power flow and full-wave conversion.[4] Alternatively, the configuration can utilize four TRIACs, each capable of conducting in both directions, simplifying the structure for lower voltage ratings while achieving similar full-wave operation.[14] In step-down frequency operation, the output waveform is generated by selectively gating the thyristors to connect segments of the input half-cycles to the load, effectively reducing the output frequency to a fraction of the input—often one-third or less—by incorporating multiple input cycles into each output half-cycle.[4] For instance, with a 50 Hz input, an output frequency of 16.67 Hz can be achieved by firing the positive bridge thyristors for three input half-cycles and the negative bridge for the subsequent three, creating a lower-frequency envelope while the fundamental output relies on the average of these selected pulses.[13] This direct synthesis relies on natural commutation from the input voltage zero-crossings, ensuring the thyristors turn off without forced methods. These converters exhibit notable limitations, including increased harmonic distortion in the output voltage and current, which becomes more pronounced at low output frequencies due to the segmented waveform construction and discontinuous conduction modes.[15] Additionally, they are generally used in low-power applications, as higher loads can amplify commutation issues and thermal stresses on the semiconductor devices.[16] An example circuit diagram for a single-phase cycloconverter with a resistive or inductive load features the input AC source connected across two anti-parallel bridges: the positive bridge (thyristors T1-T4) for positive output half-cycles and the negative bridge (T5-T8) for negative ones, with the load (R or RL) linked between the bridge outputs and a common neutral. For visualization:Input AC ---o [T1-T4 Bridge (Positive)] ---o Load (R/RL) ---o Neutral

| |

o [T5-T8 Bridge (Negative)] -----o

Input AC ---o [T1-T4 Bridge (Positive)] ---o Load (R/RL) ---o Neutral

| |

o [T5-T8 Bridge (Negative)] -----o