Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

D-flat major

View on Wikipedia| Relative key | B-flat minor |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | D-flat minor →enharmonic: C-sharp minor |

| Dominant key | A-flat major |

| Subdominant key | G-flat major |

| Enharmonic key | C-sharp major |

| Component pitches | |

| D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭, B♭, C | |

D-flat major is a major scale based on D♭, consisting of the pitches D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭, B♭ and C. Its key signature has five flats.

The D-flat major scale is:

Changes needed for the melodic and harmonic versions of the scale are written in with accidentals as necessary. The D-flat harmonic major and melodic major scales are:

Its relative minor is B-flat minor. Its parallel minor, D-flat minor, is usually replaced by C-sharp minor, since D-flat minor features a B![]() (B-double-flat) in its key signature making it less convenient to use. C-sharp major, the enharmonic equivalent to D-flat major, has seven sharps, whereas D-flat major only has five flats; thus D-flat major is often used as the parallel major for C-sharp minor. (The same enharmonic situation occurs with the keys of A-flat major and G-sharp minor, and to some extent, with the keys of G-flat major and F-sharp minor).

(B-double-flat) in its key signature making it less convenient to use. C-sharp major, the enharmonic equivalent to D-flat major, has seven sharps, whereas D-flat major only has five flats; thus D-flat major is often used as the parallel major for C-sharp minor. (The same enharmonic situation occurs with the keys of A-flat major and G-sharp minor, and to some extent, with the keys of G-flat major and F-sharp minor).

For example, in his Prelude No. 15 in D-flat major ("Raindrop"), Frédéric Chopin switches from D-flat major to C-sharp minor for the middle section in the parallel minor, while in his Fantaisie-Impromptu and Scherzo No. 3, primarily in C-sharp minor, he switches to D-flat major for the middle section for the opposite reason. Claude Debussy likewise switches from D-flat major to C-sharp minor in the significant section in his famous "Clair de lune" for a few measures. Antonín Dvořák's New World Symphony also switches to C-sharp minor for a while for the significant section in the slow movement.

In music for the harp, D-flat major is preferred enharmonically not only because harp strings are more resonant in the flat position and the key has fewer accidentals, but also because modulation to the dominant key is easier (by putting the G pedal in the natural position, whereas there is no double-sharp position in which to put the F pedal for G-sharp major).

Scale degree chords

[edit]The scale degree chords of D-flat major are:

- Tonic – D-flat major

- Supertonic – E-flat minor

- Mediant – F minor

- Subdominant – G-flat major

- Dominant – A-flat major

- Submediant – B-flat minor

- Leading-tone – C diminished

Compositions in D-flat major

[edit]Hector Berlioz called the key "majestic" in his 1856 Grand Traité d'Instrumentation et d'Orchestration modernes, while having a much different opinion of its enharmonic counterpart, calling it "Less vague; and more elegant".[1] Despite this, when he came to orchestrate Carl Maria von Weber's piano piece Invitation to the Dance in 1841, he transposed it from D-flat to D major, to give the strings a more manageable key and to produce a brighter sound.[2]

Charles-Marie Widor considered D-flat major to be the best key for flute music.[3]

Although this key was unexplored during the Baroque and Classical periods and was rarely used as the main key for orchestral works of the 18th century, Franz Schubert used it quite frequently in his sets of écossaises, valses and so on, as well as entering it and even flatter keys in his sonatas, impromptus and the like. Ludwig van Beethoven, too, used this key extensively in his second piano concerto. D-flat major was used as the key for the slow movements of Joseph Haydn's Piano Sonata Hob XVI:46 in A-flat major, and Beethoven's "Moonlight" and "Appassionata" sonatas. Chopin's Minute Waltz from Op. 64 is in D-flat major.

A part of the trio of Scott Joplin's "Maple Leaf Rag" is written in D-flat major.

The flattened pitches of D-flat major correspond to the black keys of the piano, and there is much significant piano music written in this key. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 is written in B-flat minor, but the famous opening theme is in D-flat major. Tchaikovsky composed the second movement of Piano Concerto No. 1 also in D-flat. Sergei Rachmaninoff composed the famous 18th variation of his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in this key, perhaps emphasizing the generally held view that D-flat major is the most romantically flavored of the major keys; and his friend Nikolai Medtner similarly chose it for the sensually romantic "big tune" in the last movement of his Piano Concerto No. 3 ("Ballade"). Claude Debussy also composed the famous "Clair de lune" in this key, with a significant section in C-sharp minor. Edvard Grieg composed the second movement of his Piano Concerto in D-flat. Frédéric Chopin's Nocturne in D-flat, Op. 27 and Berceuse, Op. 57 are in this key. Franz Liszt composed heavily in this key, with his most recognizable piece being the third movement of his piano composition Trois études de concert, dubbed "Un sospiro". Liszt took advantage of the piano's configuration of the key and used it to create an arpeggiating melody using alternating hands. Several of his Consolations are also written in this key.

In orchestral music, the examples are fewer. Gustav Mahler concluded his Ninth Symphony with an Adagio in D-flat major, rather than the home key of D major of the first movement. Anton Bruckner wrote the third movement of his Symphony No. 8 in D-flat major, while every other movement is in C minor. Antonín Dvořák wrote the second movement of his Symphony No. 9 in D-flat major, while every other movement is in E minor. The first piano concerto of Sergei Prokofiev is also written in D-flat major, with a short slow movement in G-sharp minor. Aram Khachaturian wrote his Piano Concerto, Op. 38 in the key of D-flat major. Choral writing explores D-flat infrequently, notable examples being Robert Schumann's Requiem, Op. 148, Gabriel Fauré's Cantique de Jean Racine[4] and Sergei Rachmaninoff's "Nunc Dimittis" from his All-Night Vigil, Op. 37. Vincent d'Indy's String Quartet No. 3, Op. 96, which is in D-flat.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Berlioz, Hector (1882). A Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration: To which is Appended the Chef D'Orchestre. Novello, Ewer. p. 24. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ The Hector Berlioz Website

- ^ Charles-Marie Widor, Manual of Practical Instrumentation translated by Edward Suddard, Revised edition. London: Joseph Williams. (1946) Reprinted Mineola, New York: Dover (2005): 11. "No key suits it [the flute] better than D-flat [major]."

- ^ Cantique de Jean Racine: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- ^ String Quartet No. 3, Op. 96 (Indy): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

External links

[edit] Media related to D-flat major at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to D-flat major at Wikimedia Commons

D-flat major

View on GrokipediaScale and Characteristics

Notes and intervals

The D-flat major scale is constructed starting from the tonic note D♭ and follows the standard major scale pattern, resulting in the ascending sequence of pitches: D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭, B♭, C, and returning to D♭ at the octave above.[1] This one-octave span demonstrates octave equivalence, where the upper D♭ sounds identical in pitch class to the starting tonic but at double the frequency, a fundamental principle in Western music theory that allows scales to be transposed across instruments and registers. The intervals between these consecutive notes adhere to the major scale formula of whole step (W), whole step (W), half step (H), whole step (W), whole step (W), whole step (W), and half step (H), providing the structural skeleton for the scale's melodic and harmonic potential.[8] This pattern ensures the scale's characteristic stepwise progression, with whole steps spanning two semitones and half steps one semitone on the chromatic scale. Acoustically, the D-flat major scale derives its bright and consonant quality from the prevalence of major thirds (four semitones) and perfect fifths (seven semitones) within its triadic constructions, intervals historically recognized for their harmonic stability and pleasing resonance due to simple frequency ratios.[9] [10] These properties contribute to the scale's uplifting tonal character, distinguishing it from more tense or ambiguous modes. The scale can be conceptually divided into two identical tetrachords separated by a whole step: the lower tetrachord comprising D♭–E♭–F–G♭ (following W–W–H) and the upper tetrachord A♭–B♭–C–D♭ (mirroring the same pattern), a pedagogical framework that highlights the scale's symmetrical construction.[11] This division underscores how the major scale builds tonal hierarchy from its foundational intervals.Key signature

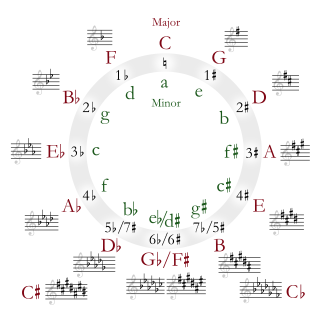

The key signature of D-flat major consists of five flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, and G♭, added in that order according to the cycle of fifths starting from B.[12][1] These flats alter the corresponding natural notes to produce the pitches required for the D-flat major scale: D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭, B♭, and C.[13] In the treble clef, the flats are positioned on the staff as follows: B♭ on the third line from the bottom (B line), E♭ on the top space (E space), A♭ on the second space from the bottom (A space), D♭ on the fourth line from the bottom (D line), and G♭ on the second line from the bottom (G line).[14] In the bass clef, the positions are: B♭ on the second line from the bottom (fourth line from the top), E♭ on the third space from the bottom, A♭ on the first space from the bottom, D♭ on the third line from the bottom (third line from the top), and G♭ on the first line from the bottom (fifth line from the top).[14] This placement ensures each flat symbol aligns precisely with the line or space of the note it modifies, facilitating clear notation at the beginning of the staff.[15] Key signatures like that of D-flat major, with five flats, represent the fifth position in the flatward direction of the circle of fifths, a diagrammatic tool that emerged in the 17th century to organize tonal relationships amid evolving tuning practices.[16] Prior to the widespread adoption of equal temperament in the 18th century, earlier systems such as meantone tuning limited the practical use of remote flat keys like D-flat major, as their multiple flattened fifths introduced dissonant "wolf" intervals that sounded out of tune.[17] The standardization of key signatures with ordered flats, including five, became common in the Baroque era as composers explored chromatic modulations, though such keys remained less frequent than those with fewer accidentals until well-tempered tunings allowed purer intonation across all keys.[18] Within compositions in D-flat major, additional accidentals beyond the key signature are relatively uncommon due to the diatonic structure of the scale, which relies on the five flats for its core pitches.[19] However, temporary sharps or naturals, such as F♯, may appear as leading tones during modulations to neighboring keys like G major, introducing chromatic tension without altering the primary signature.[20]Key Relationships

Relative and parallel keys

The relative minor of D-flat major is B-flat minor, which shares the identical key signature of five flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭).[3] This key is derived by beginning on the sixth scale degree of D-flat major—B♭—and applying the natural minor scale's interval pattern of whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step.[21] The parallel minor, D-flat minor, maintains the same tonic note (D♭) as D-flat major but features a minor third above it (D♭ to F♭), yielding the natural minor scale degrees D♭, E♭, F♭, G♭, A♭, B double flat, C♭.[22] Its key signature includes seven flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭), the same as its relative major F-flat major, explicitly notating the lowered degrees relative to D-flat major.[4] These relationships highlight structural and emotional contrasts: the relative minor facilitates modal interchange, allowing chords from B-flat minor—such as the i or iv—to be borrowed into D-flat major progressions for added color while preserving the key signature.[23] In opposition, the parallel minor enables shifts to the same tonic in a minor mode, juxtaposing the inherent brightness and optimism of D-flat major against the melancholy and introspection typical of D-flat minor.[24] B-flat minor and D-flat minor each possess enharmonic equivalents in sharp notation, A-sharp minor and C-sharp minor, respectively.[3]Enharmonic equivalents

The enharmonic equivalent of D-flat major is C-sharp major, which employs a key signature of seven sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯) rather than the five flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭) of D-flat major, resulting in identical pitches when performed.[3] This equivalence arises because both keys produce the same set of notes on instruments tuned to equal temperament, differing only in notation.[3] In practice, composers and performers often prefer D-flat major over C-sharp major due to its simpler key signature with fewer accidentals, which facilitates reading and reduces errors in performance.[25] D-flat major is particularly favored for orchestration involving flat-keyed brass instruments, such as horns in F, where the transposed parts align more naturally with the instrument's fingering and avoid excessive sharps.[26] For vocal music, the flat notation of D-flat major enhances ease of reading and singing by minimizing complex sharp alterations.[25] Conversely, C-sharp major may be selected when modulating to or from other sharp keys, or in theoretical analyses emphasizing chromatic ascent within equal temperament.[27] Historically, enharmonic equivalents like C-sharp major were rare in the Baroque era, as period tuning systems such as meantone temperament rendered the seven-sharp signature impractical due to dissonant intervals and limited usability on keyboard instruments.[28] Composers like J.S. Bach occasionally employed C-sharp major, as in the Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, but D-flat major was virtually absent, reflecting the era's avoidance of extreme flat keys.[29] In the Romantic period, however, such enharmonics became more common for coloristic effects, with Franz Liszt frequently using them in modulations to exploit dramatic tonal shifts and emotional intensity, as seen in works involving enharmonic reinterpretations via the mediant or diminished seventh chords. Regarding tuning, enharmonic equivalents like D-flat and C-sharp major are pitch-identical in equal temperament, where all semitones are evenly spaced, allowing seamless interchange.[30] In just intonation, however, slight discrepancies arise because intervals are derived from simple frequency ratios tuned to a specific key, making the two notations non-equivalent in pitch.[30] The relative minor of D-flat major, B-flat minor, shares a similar enharmonic relationship with A-sharp minor.[3]Diatonic Harmony

Scale degree chords

The diatonic chords of the D-flat major scale are constructed by stacking alternate scale degrees in root position to form triads and adding another third to create seventh chords, using only notes from the scale: D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭, B♭, C.[31][1] Roman numerals denote these chords, with uppercase indicating major quality, lowercase for minor, and ° for diminished; seventh chord symbols specify the interval above the root (M7 for major seventh, 7 for minor seventh, ø7 for half-diminished).[31] In root position, the lowest note is the root (scale degree on which the chord is built).[32] The following table lists the triads and seventh chords for each scale degree:| Scale Degree | Roman Numeral (Triad) | Triad Notes | Roman Numeral (Seventh Chord) | Seventh Chord Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | I | D♭–F–A♭ | IM7 | D♭–F–A♭–C |

| ii | ii | E♭–G♭–B♭ | ii7 | E♭–G♭–B♭–D♭ |

| iii | iii | F–A♭–C | iii7 | F–A♭–C–E♭ |

| IV | IV | G♭–B♭–D♭ | IVM7 | G♭–B♭–D♭–F |

| V | V | A♭–C–E♭ | V7 | A♭–C–E♭–G♭ |

| vi | vi | B♭–D♭–F | vi7 | B♭–D♭–F–A♭ |

| vii° | vii° | C–E♭–G♭ | viiø7 | C–E♭–G♭–B♭ |