Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flat (music)

View on WikipediaIn music, flat means lower in pitch. It may either be used in a general sense to mean any lowering of pitch, or to specifically refer to lowering pitch by a semitone. A flat is the opposite of a sharp (♯) which indicates a raised pitch in the same way.

| ♭ | |

|---|---|

Flat (music) | |

| In Unicode | U+266D ♭ MUSIC FLAT SIGN (♭) |

| Different from | |

| Different from | U+0062 b LATIN SMALL LETTER B |

| Related | |

| See also | U+1D12B 𝄫 MUSICAL SYMBOL DOUBLE FLAT U+1D12C 𝄬 MUSICAL SYMBOL FLAT UP |

The flat symbol (♭) appears in key signatures to indicate which notes are flat throughout a section of music, and also in front of individual notes as an accidental, indicating that the note is flat until the next bar line.

Pitch change

[edit]The symbol ♭ is a stylised lowercase b, derived from Italian be molle for "soft B" and German blatt for "planar, dull". It indicates that the note to which it is applied is played one semitone lower. In the standard modern tuning system, 12 tone equal temperament, this corresponds to 100 cents.[1][2]

In older tuning systems (from the 16th and 17th century), and in modern microtonal tunings, the difference in pitch indicated by a sharp or flat is normally smaller than the standard semitone. For example, in the old quarter-comma meantone system a flat lowers a note's pitch by 76.05 cents,, and in just intonation a flat commonly lowers a note's pitch by 70.57 cents. In Pythagorean tuning a flat lowers the pitch by 113.7 cents, and in well temperaments, a flat may be different sizes. Intricate systems of microtuning may replace the standard flat or sharp with different symbols for raising and lowering pitch. In 53 equal temperament tuning sharps and flats have two or three different sub-levels, and notation for flattening notes varies, but usually involves several different symbols; one of the sets of 53 TET flat symbols is ♭ (67.9 cents), ![]() (45.3 cents), and ↓ (22.6 cents), used both separately and in combinations.

(45.3 cents), and ↓ (22.6 cents), used both separately and in combinations.

Related symbols

[edit]A double flat (𝄫) lowers a note by two semitones (a whole step).

A quarter-tone flat, half flat or demiflat indicates the use of quarter tones; it may be marked with various symbols including a flat with a slash (![]() ), a flat with a 4 (𝄳),[citation needed] or a reversed flat sign (

), a flat with a 4 (𝄳),[citation needed] or a reversed flat sign (![]() ). A three-quarter-tone flat, flat and a half or sesquiflat is represented by a demiflat and a whole flat (

). A three-quarter-tone flat, flat and a half or sesquiflat is represented by a demiflat and a whole flat (![]() ). The symbols -, ↓,

). The symbols -, ↓, ![]() , among others, represent comma flat or eighth-tone flat.[a]

, among others, represent comma flat or eighth-tone flat.[a]

A triple flat (♭𝄫 or 𝄫♭) is very rare. As expected, it lowers a note by three semitones (a whole tone and semitone).[3] (For example, B♭𝄫 is enharmonic with A♭.)[4]

While this system allows for higher multiples of flats, there are only a few examples of triple flats in the literature. However, quadruple flats or beyond may be required in some non-standard tuning systems such as 53 equal temperament. A quadruple flat would be indicated by the symbol 𝄫𝄫.[citation needed]

Flats in key signatures

[edit]| Order of flats in key signatures | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The order of flats in key signatures is

- B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭

The corresponding order of keys also follows the circle of fifths sequence:

- F, B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭

Starting with no flats or sharps (C major), adding the first flat (B♭) indicates F major; adding the next (E♭) indicates B♭ major, and so on, backwards through the circle of fifths.

Some keys (such as C♭ major with seven flats) may be written as an enharmonically equivalent key (B major with five sharps in this case). In rare cases the flat keys may be extended further:

- F♭ → B𝄫 → E𝄫 → A𝄫 → D𝄫 → G𝄫 → C𝄫

requiring double flats in the key signature. These are generally avoided as impractical, and the simpler, equivalent key signature is used instead. This principle applies similarly to the sharp keys.

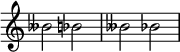

The staff below shows a key signature with three flats (E♭ major or its relative minor C minor), followed by a note with a flat preceding it: The flat symbol placed on the note indicates that it is a D♭.

In standard 12 tone equal temperament tuning, lowering a note's pitch by a semitone results in a note that is enharmonically equivalent to the adjacent named note. In this system, B♭ and A♯ are considered to be equivalent. In other, non-standard tuning systems, however, this is not the case.

Accidentals

[edit]Accidentals are placed to the left of the note head.

They apply to the note on which they are placed and to subsequent similar notes in the same measure and octave. In modern notation they do not apply to notes in other octaves, but this was not always the convention. To cancel an accidental later in the same measure and octave, another accidental such as a natural (♮) or a sharp (♯) may be used.

Other notation and usage

[edit]- Historically, raising a double flat to a single flat would be notated using a natural and flat sign (♮♭) or vice-versa (♭♮) instead of using only a flat sign (♭). In modern notation the leading natural sign is often omitted. The combination ♮♭ can be also written when changing a sharp to flat.[citation needed]

- In environments where the 𝄫 symbol is not supported, or in specific text notation, a double flat can be written with ♭♭, two lower-case b's (bb), etc. Likewise, a triple flat can also be written as ♭♭♭, etc.[citation needed]

- In environments where the

or 𝄳 symbol is not supported, or in specific text notation, a half flat can be written as a lower-case d. Likewise, a flat and a half can also be written as d♭ or db.[citation needed]

or 𝄳 symbol is not supported, or in specific text notation, a half flat can be written as a lower-case d. Likewise, a flat and a half can also be written as d♭ or db.[citation needed] - To allow extended just intonation, composer Ben Johnston uses a flat as an accidental to indicate a note is lowered 70.6 cents.[5]

Unicode

[edit]The Unicode character ♭ (U+266D) can be found in the block Miscellaneous Symbols; its HTML entity is ♭. Other assigned flat signs can be found in the Musical Symbols block and are as follows:

- U+1D12B 𝄫 MUSICAL SYMBOL DOUBLE FLAT

- U+1D12C 𝄬 MUSICAL SYMBOL FLAT UP

- U+1D12D 𝄭 MUSICAL SYMBOL FLAT DOWN

- U+1D133 𝄳 MUSICAL SYMBOL QUARTER TONE FLAT

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The size of the lowering of pitch by a "comma" varies, depending on the tuning system; it is normally 21 + 1 / 2 cents but can vary between 20–25 cents.

See also

[edit]- Electronic tuner – Device used to tune musical instruments

References

[edit]- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. 1 (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 6.

Flat (♭) lowers the pitch a half step.

- ^ Flat. Glossary. Naxos Records. Archived from the original on 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ^ a b Byrd, Donald (October 2018). "Extremes of conventional music notation". luddy.indiana.edu. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. Archived from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ a b "B-triple-flat note". Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Fonville, J. (Summer 1991). "Ben Johnston's extended just intonation – a guide for interpreters". Perspectives of New Music. 29 (2): 106–137.

... the 25 / 24 ratio is the sharp (♯) ratio ... this raises a note approximately 70.6 cents.(p 109)

External links

[edit] Media related to Flats (music) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flats (music) at Wikimedia Commons

Flat (music)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Pitch Alteration

In music, the flat symbol (♭) is an accidental that lowers the pitch of a note by one semitone, or half step, within the standard 12-tone equal temperament system prevalent in Western music.[1] A semitone represents the smallest interval in this tuning, equivalent to 100 cents, where one cent is 1/1200 of an octave.[8] For example, applying a flat to B produces B♭, which sounds at a pitch between B and A natural.[9] The precise pitch alteration effected by a flat varies across historical tuning systems, reflecting differences in how intervals are divided. In quarter-comma meantone tuning, a common Renaissance-era temperament, the lowering corresponds to the chromatic semitone of approximately 76 cents. Just intonation, which prioritizes simple frequency ratios like 3:2 for perfect fifths, yields variable semitone sizes depending on the context, with certain intervals—such as the 25:24 minor diesis—lowering by about 70.6 cents in extended applications.[10] Pythagorean tuning, based on stacking 3:2 fifths, features unequal semitones, where the flat typically lowers by either the diatonic semitone (around 90 cents) or chromatic semitone (around 114 cents), depending on the note's position in the scale.[11] Multiple flats extend this alteration: a double flat (𝄫) lowers a note by two semitones, equivalent to a diatonic whole step or 200 cents in equal temperament, such that B𝄫 equals A natural.[9] The triple flat (♭𝄫), which lowers by three semitones or 300 cents, is rare and primarily appears in extended microtonal contexts, such as 53 equal temperament, where it facilitates precise approximations of just intervals beyond standard notation.[12] Quadruple flats remain a theoretical extreme, seldom used in practice.[13]Notation and Appearance

The flat symbol (♭) is a stylized glyph resembling a lowercase "b" rotated 180 degrees, with a curved stem and a compact loop, designed for clarity within the dense layout of a musical staff. This visual form derives from the medieval "b molle" (soft b), a rounded variant of the letter "b" used in Gregorian chant notation to denote the lowered pitch associated with B-flat in the hexachord system, distinguishing it from the "b durum" (hard b) for B-natural.[14] In standard notation, the flat is placed immediately to the left of the note head it modifies, centered vertically at the same level as the note head's centerline to maintain optical alignment and avoid cluttering the staff. For key signatures, flats follow a fixed sequence (B, E, A, D, G, C, F) and occupy specific positions on the staff lines or spaces corresponding to those notes; for example, in the treble clef, the initial flat for B♭ appears on the middle line, while in the bass clef, it is placed on the third line from the bottom to align with the B position in that clef. This placement ensures the symbol integrates seamlessly with the staff's grid, applying the alteration to all instances of the affected note within the designated range.[15][16] The symbol's size is standardized to match the diameter of the note head, promoting uniformity and readability across the page. In printed editions, flats adhere to precise typographic fonts, appearing crisp and proportional, whereas handwritten manuscripts often feature more fluid, italicized styles with variable thickness, reflecting the engraver's or copyist's personal flourish. For illustration, a single flat preceding an F on the staff is rendered as ♭F in the treble clef, positioning the symbol just left of the note head on the top line; the same convention applies in the bass clef, where ♭F would align similarly but affect the note's pitch relative to the lower register.[16] Historically, flats in pre-19th-century manuscripts varied in execution, appearing as larger, more ornate rounded "b"s occasionally fused with neighboring marks or drawn with irregular curves due to quill-based copying. From the mid-19th century onward, advancements in pewter plate engraving and later lithographic processes established consistent sizing, spacing, and curvature, as codified in professional guidelines, ensuring the symbol's modern, compact appearance across printed scores. The double flat (𝄫), formed by vertically stacking two flats with minimal overlap, follows analogous placement rules for greater alterations.[17]Related Symbols

Standard Alterations: Sharps, Naturals, and Double Flats

In standard Western music notation, accidentals are symbols placed before a note to temporarily alter its pitch from that indicated by the key signature. The flat (♭) lowers the pitch by one semitone, the sharp (♯) raises it by one semitone, and the natural (♮) cancels any previous sharp or flat, restoring the original pitch dictated by the key signature.[1][4] The double flat (𝄫), visually represented as two flat symbols stacked vertically, lowers a pitch by two semitones (a whole step). It is employed to maintain logical voice leading or to avoid excessive ledger lines; for instance, notating B𝄫 (equivalent to A natural) keeps the note on the staff line in contexts where changing to A might disrupt melodic continuity.[1][18] Accidentals interact cumulatively within a measure unless canceled. A natural sign cancels a preceding flat, returning the note to its unaltered state, while applying a sharp to a flatted note results in the natural pitch, as the alterations offset each other.[19][1] To illustrate stepwise alterations, consider the note C as the starting point: C natural is the baseline; C♯ raises it by one semitone; C♭ lowers it by one semitone (enharmonically equivalent to B natural); and C𝄫 lowers it by two semitones (enharmonically equivalent to B♭). Similarly, B𝄫 equates to A natural, demonstrating enharmonic equivalence where different notations produce the same sound.[20][4] Double flats appear frequently in minor keys, particularly for chromatic alterations, and in modal music to adjust sensible notes within scales. Historically, they emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries to facilitate modal adjustments during the transition to tonal systems, such as notating B𝄫 in certain modal passages to maintain voice leading.[18]Extended and Microtonal Variants

The triple flat, denoted as ♭♭♭ or ♭𝄫 (proposed Unicode U+1D260, not yet encoded as of 2025), lowers a note by three semitones and is employed in rare instances within atonal or microtonal compositions to maintain intervallic relationships in complex harmonic structures.[21][22] For example, in 53 equal temperament, where each step approximates 22.64 cents, the triple flat facilitates precise pitch adjustments beyond standard 12-tone equal temperament. Its usage remains experimental, primarily in contemporary works exploring extended tonalities. Their usage is highly experimental and not part of standard Western notation, appearing mainly in theoretical discussions or avant-garde compositions.[22] The quadruple flat, represented as stacked ♭♭♭♭ or ♭𝄫♭ (proposed but not yet encoded in Unicode as of 2025), theoretically lowers a pitch by four semitones and appears in discussions of non-standard tuning systems, such as extended equal temperaments, though practical implementations are scarce.[22] This symbol underscores the adaptability of accidental notation to accommodate finer divisions of the octave in theoretical contexts. Microtonal variants of the flat extend pitch alteration to fractions of a semitone, enabling notations for intervals smaller than 100 cents. The quarter-tone flat, symbolized as 𝄳 (U+1D133) or approximately ♭̰, lowers a note by 50 cents, commonly used in 24-tone equal temperament to represent quarter-tone inflections in Middle Eastern or contemporary Western music.[23] In just intonation systems, Ben Johnston's extended framework uses the flat to lower by the 25:24 ratio (approximately 70 cents from equal temperament), distinct from the standard demiflat (quarter-tone flat at 50 cents), often notated with additional modifiers like slashes for further precision.[24] Notation for these extended flats typically involves stacked symbols for multiples, such as triple flats combining three flat signs, or modified forms like slashed flats for microtonal adjustments, ensuring clarity in scores for non-diatonic tunings.[23] In informal or textual contexts, abbreviations like "bbb" denote triple flats, building on conventions for double flats ("bb").[25] These variants find application in contemporary genres such as spectralism, where harmonic spectra demand precise microtonal deviations, and xenharmonics, an experimental field exploring novel scale structures beyond 12 tones.[25] Their status as non-standard symbols highlights ongoing efforts to standardize microtonal representation in music theory.[22]Core Applications in Music Theory

As Accidentals

In music notation, the flat (♭) functions as an accidental that temporarily lowers the pitch of a note by one semitone from its position in the prevailing key signature. This alteration applies to the affected note and all subsequent instances of the same pitch within the same octave in that measure, extending until the next bar line or until another accidental—such as a natural (♮), sharp (♯), or different flat—cancels it. Unlike key signature flats, which apply persistently throughout the score, these measure-specific flats create chromatic variations without altering the overall tonality.[26] By the 18th century, accidentals began to apply specifically to the same note in the same octave within a bar, a convention that became standardized in modern notation to reduce ambiguity in multi-octave passages. Courtesy flats, often parenthesized for clarity, serve as optional reminders at the start of a new measure when the same pitch was altered in the previous one, helping performers avoid errors without being strictly required by notation rules.[27] For instance, if a B♭ appears near the end of one measure, a courtesy ♭ may precede the B at the measure's start to confirm the continuation of the lowered pitch.[27] Accidentals override any flats present in the key signature for their duration. In the key of F major, which includes a B♭, a double flat (♭♭) before a B would lower it to B♭♭ (enharmonically A), demonstrating how accidentals can intensify or modify established key alterations.[9] A common example occurs in C major, which has no key flats: placing a ♭ before an E produces E♭, altering all subsequent E's in that octave for the measure and introducing a minor third interval from the tonic.[28] In chromatic progressions, subsequent accidentals on the same pitch override prior ones, applying their alteration to remaining notes in the measure until canceled. In vocal music, a flat accidental applies to the specific note sung on its corresponding syllable, ensuring precise intonation within melodic lines that align text and pitch.[29] Rare cases arise in orchestral scores involving transposing instruments, such as clarinets in B♭, where imported or multi-instrument notations may produce unusual stacked flats (e.g., ♭♭ in transposed contexts) to maintain correct sounding pitch, though these are avoided in standard engraving.[30]In Key Signatures

In key signatures, flats are arranged in a specific order at the beginning of the musical staff to indicate the tonal center of a piece, following the counterclockwise progression of the circle of fifths, which corresponds to descending perfect fifths or subdominant relationships between keys.[31] The standard order of flats is B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, added sequentially as the number of flats increases.[5] A common mnemonic to remember this sequence is "Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles' Father."[32] This ordering ensures that each new flat lowers the subdominant note by a perfect fifth from the previous key, facilitating diatonic harmony.[31] The number of flats in a key signature determines the associated major and relative minor keys, with the penultimate flat (second-to-last) identifying the tonic for major keys. For instance, one flat indicates F major or its relative D minor, while six flats indicate G♭ major or E♭ minor. The following table summarizes the major and minor keys by the number of flats:| Number of Flats | Major Key | Relative Minor Key |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | C major | A minor |

| 1 | F major | D minor |

| 2 | B♭ major | G minor |

| 3 | E♭ major | C minor |

| 4 | A♭ major | F minor |

| 5 | D♭ major | B♭ minor |

| 6 | G♭ major | E♭ minor |

| 7 | C♭ major | A♭ minor |