Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

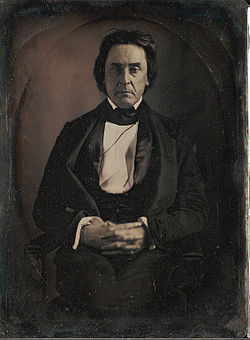

David Rice Atchison

View on Wikipedia

David Rice Atchison (August 11, 1807 – January 26, 1886) was a mid-19th-century Democratic[1] United States Senator from Missouri.[1] He served as president pro tempore of the United States Senate for six years.[2] Atchison served as a major general in the Missouri State Militia in 1838 during Missouri's Mormon War and as a Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War under Major General Sterling Price in the Missouri Home Guard. Some of Atchison's associates claimed that for 24 hours—Sunday, March 4, 1849, through noon on Monday—he may have been acting president of the United States. This belief, however, is dismissed by most scholars.[2][3]

Key Information

Atchison, owner of many slaves and a plantation, was a prominent pro-slavery activist and border ruffian leader, deeply involved with violence against abolitionists and other free-staters during the "Bleeding Kansas" events that preceded admission of the state to the Union.[4][5][6][7]

Early life

[edit]Atchison was born to William Atchison and his wife in Frogtown (later Kirklevington), which is now part of Lexington, Kentucky. He was educated at Transylvania University in Lexington. Classmates included five future Democratic senators (Solomon Downs of Louisiana, Jesse Bright of Indiana, George Wallace Jones of Iowa, Edward Hannegan of Indiana, and Jefferson Davis of Mississippi). Atchison completed law studies and was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1829.[8]

Missouri lawyer and politician

[edit]In 1830, he moved to Liberty in Clay County in western Missouri,[8] and set up practice there. He also acquired a farm or plantation, with labor provided by enslaved African Americans. Atchison's law practice flourished, and his best-known client was Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint Movement.[9] Atchison represented Smith in land disputes with non-Mormon settlers in Caldwell County[9] and Daviess County.[9]

Alexander William Doniphan joined Atchison's law practice in Liberty in May 1833.[10] The two became fast friends and spent many leisure time hours playing cards, going to horse races, hunting, fishing, and attending social functions and political events. Atchison, already a member of the Liberty Blues, a volunteer militia in Missouri, got Doniphan to join.[11]

Atchison was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives in 1834.[12][13] He worked hard for the Platte Purchase, which required Native American tribes to cede land to the United States and extended the northwestern boundary of Missouri to the Missouri River in 1837.

When early disputes broke out into the Mormon War of 1838, Atchison was appointed a major general in the state militia.[14] He took part in suppressing violence by both sides.

Active in the Democratic Party, Atchison was re-elected to the Missouri State House of Representatives in 1838. In 1841, he was appointed a circuit court judge for the six-county area of the Platte Purchase. In 1843, he was named a county commissioner in Platte County, where he then lived.

Senate career

[edit]

In October 1843,[9] Atchison was appointed to the U.S. Senate to fill the vacancy left by the death of Lewis F. Linn. He was the first senator from western Missouri to serve in this position.[9] At age 36, he was the youngest senator from Missouri up to that time.[9] Atchison was re-elected to a full term on his own account in 1849.[9]

Atchison was very popular with his fellow Senate Democrats. When the Democrats took control of the US Senate in December 1845, they chose Atchison as president pro tempore,[14] placing him second in succession for the presidency.[15] He also was responsible for presiding over the Senate when the vice president was absent. At 38, he was a young man with low seniority in the Senate after two years to gain such a position.

In 1849, Atchison stepped down as president pro tempore in favor of William R. King.[14] King, in turn, yielded the office back to Atchison in December 1852, after being elected Vice President of the United States. Atchison continued as president pro tempore until December 1854.[14]

As a senator, Atchison was a fervent advocate of slavery[14] and territorial expansion. He supported the annexation of Texas and the U.S.-Mexican War. Atchison and Thomas Hart Benton, Missouri's other senator, became rivals and finally enemies, although both were Democrats. Benton declared himself to be against slavery in 1849. In 1851 Atchison allied with the Whigs to defeat incumbent Benton for re-election.

Benton, intending to challenge Atchison in 1854, began to agitate for territorial organization of the area west of Missouri (now the states of Kansas and Nebraska) so that it could be opened to settlement. To counter this, Atchison proposed that the area be organized and that the section of the Missouri Compromise banning slavery there be repealed in favor of popular sovereignty. Under this plan, settlers in each territory would vote to decide whether they would allow slavery.

At Atchison's request, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois introduced the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which embodied this idea, in November 1853. The act was passed and became law in May 1854, establishing the Territories of Kansas and Nebraska.

Border ruffians

[edit]Both Douglas and Atchison had believed that Nebraska would be settled by Free-State men from Iowa and Illinois, and Kansas by pro-slavery Missourians and other Southerners, thus preserving the numerical balance between free states and slave states in the nation. In 1854 Atchison helped found the town of Atchison, Kansas, as a pro-slavery settlement. The town (and county) were named for him.[16]

While Southerners supported the idea of settling in Kansas, few migrated there. Most free-soilers preferred Kansas to Nebraska. Furthermore, anti-slavery activists throughout the North came to view Kansas as a battleground and formed societies to encourage free-soil settlers to go to Kansas, to ensure there would be enough voters in both Kansas and Nebraska to approve their entry as free states.[17]

It appeared as if the Kansas Territorial legislature to be elected in March 1855 would be controlled by free-soilers and ban slavery. Atchison and his supporters viewed this as a breach of faith. An angry Atchison called on pro-slavery Missourians to uphold slavery by force and "to kill every God-damned abolitionist in the district" if necessary.[18] He recruited an immense mob of heavily armed Missourians, the infamous "border ruffians". On election day, March 30, 1855, Atchison led 5,000 border ruffians into Kansas. They seized control of all polling places at gunpoint, cast tens of thousands of fraudulent votes for pro-slavery candidates, and elected a pro-slavery legislature.[17]

The outrage was nonetheless accepted by the Federal government. When Territorial Governor Andrew Reeder objected, President Franklin Pierce fired him.

Despite this show of force, far more free-soilers than pro-slavery settlers migrated to Kansas. There were continual raids and ambushes by both sides in "Bleeding Kansas". In spite of the best efforts of Atchison and the Ruffians, Kansas rejected slavery and finally became a free state in 1861.

Charles Sumner, in the epic "Crimes Against Kansas" speech on May 19, 1856, exposed Atchison's role in the invasion, tortures, and killings in Kansas. Speaking in the flamboyant style he and others used, lacing his prose with references to Roman history, Sumner compared Atchison to Roman Senator Catiline, who betrayed his country in a plot to overthrow the existing order. For two days, Sumner listed crime, after crime, in detail, complete with documentation by newspapers and letters of the time, showing the tortures and violence by Atchison and his men.[19]

Two days later, Atchison gave his own speech, totally unaware that he had been exposed on the Senate floor in such a fashion. Atchison's speech was to the Texas men he had just met, hired, and paid for, Atchison reveals in his speech, by "authorities in Washington". They are about to invade Lawrence, Kansas. Atchison makes the men promise to kill and "draw blood," and boasts of his flag, which was red in color for "Southern Rights" and the color of blood. They would press "to blood" the spread of slavery into Kansas. He revealed in this speech that the immediate goal of the invasion was to stop the newspaper in Lawrence from publishing anti-slavery material. Atchison's men had made it a crime to publish anti-slavery newspapers in Kansas.[20]

Atchison made it clear the men were to kill and draw blood, told the men they would be "well paid," and encouraged them to plunder from the homes that they invaded. That was after the hundreds of dozens of tortures and killings that Sumner had detailed in his Crimes Against Kansas speech. In other words, things were about to get much worse since Atchison had his hired men from Texas.[19]

Defeated for re-election

[edit]Atchison's Senate term expired on March 3, 1855. He sought election to another term, but the Democrats in the Missouri legislature were split between him and Benton, while the Whig minority put forward their own man. No senator was elected until January 1857, when James S. Green was chosen.

Railroad proposal

[edit]When the first transcontinental railroad was proposed in the 1850s, Atchison called for it to be built along the central route (from St. Louis through Missouri, Kansas, and Utah), rather than the southern route (from New Orleans through Texas and New Mexico). Naturally, his suggested route went through Atchison.

American Civil War

[edit]Atchison and his law partner Doniphan fell out over politics in 1859–1861, disagreeing on how Missouri should proceed. Atchison favored secession, while Doniphan was torn and would remain, for the most part, non-committal. Privately, Doniphan favored the Union, but found it difficult to oppose his friends and associates.[11]

During the secession crisis in Missouri at the beginning of the American Civil War, Atchison sided with Missouri's pro-Confederate governor, Claiborne Jackson. He was appointed a major general in the Missouri State Guard. Atchison actively recruited State Guardsmen in northern Missouri and served with Guard commander General Sterling Price in the summer campaign of 1861. In September 1861, Atchison led 3,500 State Guard recruits across the Missouri River to reinforce Price and defeated Union troops that tried to block his force in the Battle of Liberty.

Atchison served in the State Guard through the end of 1861. In March 1862, Union forces in the Trans-Mississippi theater won a decisive victory at Pea Ridge in Arkansas and secured Union control of Missouri. Atchison then resigned from the army over reported strategy arguments with Price and moved to Texas for the duration of the war. After the war, he retired to his farm near Gower. He denied many of his pro-slavery public statements made prior to the Civil War. Then, his retirement cottage outside of Plattsburg, Missouri burned to the ground before he died in 1886. This entailed the complete loss of his library containing books, documents, and letters documenting his role in the Mormon War, Indian affairs, pro-slavery activities, Civil War activities, and other legislation covering his career as a lawyer, senator, and soldier.

Purported one-day presidency

[edit]Inauguration Day—March 4—fell on a Sunday in 1849, and so president-elect Zachary Taylor did not take the presidential oath of office until the next day out of religious concerns. Even so, the term of the outgoing president, James K. Polk, ended at noon on March 4. On March 2, outgoing vice president George M. Dallas relinquished his position as president of the Senate. Congress had previously chosen Atchison as president pro tempore. In 1849, according to the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, the Senate president pro tempore immediately followed the vice president in the presidential line of succession. As Dallas's term also ended at noon on the 4th, and as neither Taylor nor vice president-elect Millard Fillmore had been sworn into office on that day, it was claimed by some of Atchison's friends and colleagues that from March 4 to 5, 1849, Atchison was acting president of the United States.[21][22]

Historians, constitutional scholars, and biographers dismiss the claim. They point out that Atchison's Senate term had also ended on March 4.[3] When the Senate of the new Congress convened on March 5 to allow new senators and the new vice president to take the oath of office, the secretary of the Senate called members to order, as the Senate had no president pro tempore.[21] Although an incoming president must take the oath of office before any official acts, the prevailing view is that presidential succession does not depend on the oath.[3] Even supposing that an oath was necessary, Atchison never took it, so he was no more the president than Taylor.[3]

In September 1872, Atchison, who never himself claimed that he was technically president,[3] told a reporter for the Plattsburg Lever:

It was in this way: Polk went out of office on March 3, 1849, on Saturday at 12 noon. The next day, the 4th, occurring on Sunday, Gen. Taylor was not inaugurated. He was not inaugurated till Monday, the 5th, at 12 noon. It was then canvassed among Senators whether there was an interregnum (a time during which a country lacks a government). It was plain that there was either an interregnum or I was the President of the United States being chairman of the Senate, having succeeded Judge Mangum of North Carolina. The judge waked me up at 3 o'clock in the morning and said jocularly that as I was President of the United States he wanted me to appoint him as secretary of state. I made no pretense to the office, but if I was entitled in it I had one boast to make, that not a woman or a child shed a tear on account of my removing any one from office during my incumbency of the place. A great many such questions are liable to arise under our form of government.[23]

Death

[edit]

Atchison died on January 26, 1886, at his home near Gower, Missouri at the age of 78. He was buried at Greenlawn Cemetery in Plattsburg, Missouri. His grave marker reads "President of the United States for One Day."

Legacy

[edit]- Atchison, Kansas[24] county seat of Atchison County, Kansas.

- The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad utilized the town name.

- Atchison County, Missouri

- Atchison Township, Clinton County, Missouri

- Atchison Township, Nodaway County, Missouri

- USS Atchison County (LST-60) ship

- In 1991, Atchison was inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians, and a bronze bust depicting him is on permanent display in the rotunda of the Missouri State Capitol.[25]

- The Atchison County Historical Museum, in Atchison, Kansas, includes an exhibit titled the "World's Smallest Presidential Library".[26]

- A historical marker designating the approximate site of Atchison's birth is located along Highway 1974 in the Landsdowne neighborhood of Lexington, Kentucky.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "David Rice Atchison Biography". Who2.com. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ a b "1801: President for a Day – March 4, 1849". United States Senate. May 29, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Christopher Klein (February 18, 2013). "The 24-Hour President". The History Channel. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ McPherson, James M., Battle Cry of Freedom, Penguin Books, 1990, ISBN 978-0-14-012518-4 pp. 145–148

- ^ Stampp, Kenneth, America in 1857: a nation on the brink, Oxford University Press US, 1992, ISBN 0-19-507481-5, p. 145

- ^ Grimsted, David, American Mobbing, 1828–1861: Toward Civil War, Oxford University Press US, 2003, ISBN 0-19-517281-7, p. 256

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Secessionists triumphant, 1854–1861, Oxford University Press US, 2007, ISBN 0-19-505815-1, pp. 72–73

- ^ a b "Atchison, David Rice (1807–1886)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Hall of Famous Missourians". House.mo.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ "Kansas Bogus Legislature – Alexander W. Doniphan". Kansasboguslegislature.org. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Muench, James F., (2006). Five Stars: Missouri's Most Famous Generals. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-8262-1656-4.

- ^ "Index to Politicians: Ashley-Cotleur to Ather". The Political Graveyard. 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ "Missouri History: Missouri State Legislators, 1820–2000". Office of the Missouri Secretary of State. 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "The Other 12th U.S. President: David Rice Atchison". Trivia-Library. 2013. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Kansas Profile – Now That's Rural Archived September 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of the State of Kansas by William G. Cutler – 1883". Kancoll.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2003. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ a b Billings, R. A. (1949). Westward Expansion. New York: Macmillan. pp. 599–601.

- ^ David M. Potter, Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Impending Crisis 1848–1861 at 203 (Harper, 1976)

- ^ a b "Full text of 'The crime against Kansas. Speech of Hon. Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts. In the Senate of the United States, May 19, 1856'". archive.org. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ "Copy of David R. Atchison speech to proslavery forces – Kansas Memory". www.kansasmemory.org. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b "President for a Day: March 4, 1849". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Feerick, John D.; Freund, Paul A. (1965). From Failing Hands: the Story of Presidential Succession. New York City: Fordham University Press. pp. 100–101. LCCN 65-14917.

- ^ "Clinton Co. Historical Society".

- ^ "Profile for Atchison, Kansas". ePodunk. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ Winterton, Wayne (2015). Stories from History's Dust Bin. Xlibris US. ISBN 9781514419922.

- ^ "Thanks for visiting Atchison County's Museum". Atchison County Historical Museum. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "Lexington, Kentucky: One-Day President Birthplace". roadsideamerica.com. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "David Rice Atchison (id: A000322)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- David Rice Atchinson: On Being President For A Day – Original Letters Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Atchison, David R.". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 158.

Johnson, Rossiter, ed. (1906). "Atchison, David R.". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. Boston: American Biographical Society. p. 158.- Urban Legends: President for a Day

- Another view of the President for a Day claim

- Useless Information: David Rice Atchison

- U.S. Senate Historical Minute Essay

- McAfee, John J. (1886). Kentucky politicians : sketches of representative Corncrackers and other miscellany. Louisville, Kentucky: Press of the Courier-Journal job printing company. pp. 10–16.

David Rice Atchison

View on GrokipediaDavid Rice Atchison (August 11, 1807 – January 26, 1886) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician from Missouri who served as a United States Senator from 1843 to 1855.[1] Born in Kentucky and educated at Transylvania University, he moved to Missouri in 1830, where he practiced law, served in the state legislature, and acted as a circuit judge before his appointment to the Senate to fill a vacancy.[1] Elected president pro tempore of the Senate a record sixteen times between 1846 and 1854, Atchison presided over the chamber during the frequent absences of Vice President George M. Dallas.[2] A leading advocate for the expansion of slavery into western territories, he chaired the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and played a pivotal role in securing the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and introduced popular sovereignty on the issue of slavery, thereby igniting the border conflicts later termed Bleeding Kansas.[2][3] Atchison organized pro-slavery incursions from Missouri into Kansas to influence territorial elections and ensure slavery's foothold, aligning with "Border Ruffians" in efforts that escalated violence between pro- and anti-slavery settlers.[4][3] After leaving the Senate, he sympathized with the Confederate cause during the Civil War but did not hold military office.[1] He is also associated with a longstanding myth claiming he acted as president for one day on March 4, 1849—due to a gap between President James K. Polk's term ending at noon and President-elect Zachary Taylor's inauguration delayed until March 5 amid a Sunday Sabbath observance—but Atchison denied ever assuming or exercising presidential powers, and constitutional scholars dismiss the notion as he was not sworn into the role and the presidency's continuity precluded any vacancy.[4][5]