Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

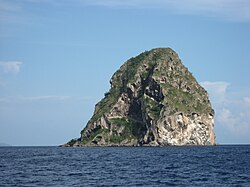

Diamond Rock

View on WikipediaDiamond Rock (French: Rocher du Diamant) is a 175-meter-high (574-foot)[1] basalt island located south of "Grande Anse du Diamant" before arriving from the south at Fort-de-France, the main port of the Caribbean island of Martinique. The uninhabited island is about 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) from Pointe Diamant and its area is 5.3 ha ( 13.1 acres ) .

Key Information

The island gets its name from the reflections that its sides cast at certain hours of the day, which evoke images of a precious stone. It is notable for having been commissioned into the Royal Navy as the stone frigate HMS Diamond Rock in February 1804 during the Napoleonic Wars. In mid-1805, a Franco-Spanish squadron captured the rock in the Battle of Diamond Rock and held it until the British recaptured it in the invasion of Martinique in 1809. Diamond Rock was returned to French control as part of a postwar trade of Martinique in 1815, and it remains part of Martinique.

HMS Diamond Rock

[edit]

Diamond Rock occupies a strategic position at the north end of the Saint Lucia Channel. Possession of the rock permits interdiction of navigation between Martinique and its southern neighbour, Saint Lucia.

In September 1803 Commodore Sir Samuel Hood sailed to the rock aboard Centaur (Captain Murray Maxwell). Hood had received the assignment to blockade the bays at Fort Royal and Saint Pierre, Martinique.

Centaur was lying at anchor in Fort Royal Bay, Martinique, on the morning of 1 December when lookouts sighted a schooner with a sloop in tow about six miles (9.7 km) off making for Saint Pierre. Hood sent his advice boat, Sarah, after the sloop, and had Maxwell sail Centaur in pursuit of the schooner. After a pursuit of some 24 leagues (120 km; 63 nmi), Centaur captured the schooner, which turned out to be the privateer Ma Sophie, out of Guadeloupe. She had a crew of 45 men, and was armed with eight guns, which she had jettisoned during the chase.[2][a]

Hood took Ma Sophie into service as a tender, charging her captain, Lieutenant William Donnett, with watching the channel between Diamond Rock and Martinique for enemy vessels. Donnett made frequent visits to the rock to gather the thick, broad-leaved grass to be woven into sailors' hats, and a spinach-like plant called callaloo, that when boiled and served daily, kept the crews of Centaur and Ma Sophie from scurvy and was a nice addition to a menu too long dominated by salt beef.[3]

Aided by calm weather, the British were able to run lines ashore and hoist two 18-pounder cannons to the summit of the rock.[1][4] The British hastily built fortifications and supplied the position with food and water for a garrison of two lieutenants and 120 men under the command of Lieutenant James Wilkes Maurice, Hood's first lieutenant.[b] Hood officially commissioned the island as the "sloop" HMS Diamond Rock (a "stone frigate"). A six-gun sloop, designated HMS Fort Diamond, supported the fort.[5] In honour of his admiral, Maurice designated as "Hood Battery" the one 24-pounder that he placed to fire from a cave halfway up the side of the rock. The British also placed two 24-pounder guns in batteries ("Centaur" and "Queen's") at the base of the rock, and a 24-pounder carronade to cover the only landing-place.[c] One account puts two 24-pounders on the summit, but all other accounts put 18-pounders there.[d] At some point during this, Ma Sophie exploded for unknown reasons, killing all but one of her crew.[9]

With work complete by 7 February, Hood decided to formalise the administration of the island, and wrote to the Admiralty, announcing that he had commissioned the rock as a sloop-of-war, under the name Diamond Rock.[10] Lieutenant Maurice, who had impressed Hood with his efforts while establishing the position, was rewarded by being made commander.[11]

While HMS Diamond Rock was in commission as a stone frigate, Royal Navy ships were required, when passing the island, to show due respect, personnel on the upper deck standing at attention and facing the rock whilst the bridge saluted.[12] Caves on the rock served as sleeping quarters for the men; the officers used tents. A court martial would reprimand Lieutenant Roger Woolcombe at Plymouth on 7 December 1805 for "conduct unbecoming a gentleman" for having messed (eaten) at the top of the rock with part of the ship's company.[13] The sailors used pulleys and ropes to raise supplies to the summit. To augment their uncertain food supply, the garrison had a small herd of goats and a flock of guinea hens and chickens that survived on the meager foliage. The British also established a hospital in a cave at the base of the rock that became a popular place to put sailors and marines recovering from fevers or injuries.[14]

Just before Centaur left the rock, a party of slaves made a clandestine visit to the rock at night to trade fruits and bananas. They brought the news that a French lieutenant colonel of engineers had arrived at their plantation to survey the heights opposite for a mortar battery with which to shell the rock. One of the slaves had been sold by his English owner to the French when the owner left the islands. He did not like his new master and claimed the protection of the British flag. Hood granted him that protection, and promised that the man could serve in the Royal Navy as a free man in return for guiding a landing party to his now-former master's house. A 23-man landing party, including the guide, and under Lieutenant Reynolds, landed at midnight, walked the four kilometers to the plantation house, and took the engineer and 17 soldiers prisoner, before returning safely to Centaur. Apparently the lieutenant colonel was the only engineer on Martinique, and so no mortar battery materialized.[15]

On 23 June 1804, whilst Fort Diamond was on a provisioning expedition at Roseau Bay, St. Lucia, a French boarding party from a schooner came up to her in two rowboats, boarding her at night while most of the crew were asleep below decks. A subsequent court-martial aboard HMS Galatea at English Harbour, Antigua, convicted Acting Lieutenant Benjamin Westcott of allowing his vessel to be captured.[16] The board dismissed him from the Royal Navy, never to be permitted to serve in the navy again.[4][17] He became an American citizen three years later.

For 17 months, the fort was able to harass French shipping trying to enter Fort-de-France.[4][18] The guns on the rock completely dominated the channel between it and the main island, and because of their elevation, were able to fire far out to sea. This forced vessels to give the rock a wide berth, with the result that the currents and strong winds would make it impossible for them to reach Fort Royal in a single tack, allowing them to be intercepted by the other blockading ships.[19] During this time the French troops on Martinique made several unsuccessful attempts to retake the rock.

Napoleonic Wars

[edit]

When Admiral Villeneuve embarked on his 1805 voyage to Martinique, he was under orders from Napoleon to recapture Diamond Rock. The French-Spanish combined naval force of 16 ships[20] under French Captain Cosmao-Kerjulien attacked Diamond Rock. Between 16 May and 29 May, the French fleet completely blockaded the rock. On the 25th, the French were able to cut out from under Maurice's guns a British sloop that arrived from St. Lucia with some supplies.[21]

The actual assault came on 31 May, and the French were able to land some troops on the rock. Maurice had anticipated the landing and had moved his men from the indefensible lower works to positions further up, and on the summit. Once the French landed, the British fire trapped the landing party in two caves near sea level.[22]

Unfortunately for the garrison, their stone cistern had cracked due to an earth tremor. This meant they were short of water and after exchanging fire with the French, they were also almost out of ammunition.[23] After enduring a fierce bombardment, Maurice surrendered to the superior force on 3 June 1805,[20] having resisted two French seventy-fours, a frigate, a corvette, a schooner, and eleven gunboats.[1] The British lost two men killed and one wounded, and the French 20 dead and 40 wounded (English account), or 50 dead and wounded (French account), and three gunboats.[e]

The French took the garrison of 107 men as prisoners, splitting them between their two 74-gun ships of the line, Pluton and the ex-British Berwick.[26] The French repatriated the prisoners to Barbados by 6 June.[27] The subsequent court-martial of Commander Maurice for the loss of his "ship" (i.e. the fort) exonerated him, his officers, and men and commended him for his defence.[24] Maurice took dispatches to England, where he arrived on 3 August, and was given command of the brig-sloop Savage.

The rock remained in French hands until 1809, when the British recaptured it in the invasion of Martinique.[28] When Martinique was traded back to France in 1815, Diamond Rock was included, and it has not traded hands since.

Battle of Diamond Rock in literature

[edit]There is a now-obscure poem of some forty four-line stanzas based on the incident, titled "The Diamond Rock".[29]

The author "Sea Lion" (the pseudonym of Geoffrey Bennett, a career naval officer), based his 1950 novel The Diamond Rock on the 1804 event, as did Dudley Pope in his 1976 novel Ramage's Diamond.

A song called "The Island of Diamond Rock" released in January 2024, by Keyes, has the British classification of the island as a ship as its main subject.[30]

Natural history

[edit]The rock is a volcanic plug, a remnant of the strong volcanic activity that affected the region some one million years ago. However, a Captain Hansen of the Norwegian steamship Talisman reported that on 13 May 1902, he observed what he took to be a volcanic eruption from a hole in the rock. This was at the time of the devastating volcanic eruption of Mount Pelée that destroyed Saint Pierre. Hansen did not investigate further.[31]

Like the other 47 islets that circle Martinique, the rock has its own ecological characteristics. It is sunnier than the main island, drier, and subject to a long seasonal dry period. Today[when?] it is covered in undergrowth and cacti.

Relatively inaccessible and inhospitable, the island is uninhabited, which has permitted it to remain a sanctuary for a species that had been believed to be extinct.[32] A nature survey has suggested that Diamond Rock is probably the last refuge for a species of reptile once endemic to Martinique, the couresse grass snake (Liophis cursor).[33][34] This snake was last seen on Martinique in 1962 and has not been encountered since then. It is now considered to be extinct.[35]

Important Bird Area

[edit]The rock has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports breeding populations of brown boobies, brown noddies and bridled terns.[36]

Diving around the island

[edit]Below water, the Diamond Rock cavern, a deep triangular cave, is a popular attraction for scuba divers. The cave is said to contain prolific quantities of beautiful sea fans and corals, though strong currents make diving around the island a risky venture.[citation needed]

One of the rock's cannon that the French had toppled from the summit has been reported to have been found on a dive.[37]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sarah too captured the sloop she had pursued. The sloop was a prize that Ma Sophie had cut out of Courland Bay, Tobago, and that had on board only a few hogsheads of sugar.

- ^ A contemporary print of the main characters involved spells his name "Morris".

- ^ The 24-pounders came from Centaur.[6]

- ^ Boswall is the source for there being 24-pounders on the summit.[7] Aspinall mentions that the two 18-pounders hauled to the top came from Hippomenes.[8] Actually, Hippomenes brought the two 18-pounders from the gun wharf at English Harbour, Antigua.[6]

- ^ For full English and French accounts, see the Naval Chronicle.[24][25]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Tour Of The Caribbean – No Flint Grey and the Stone Ship (1925) Old and Sold Antiques Digest

- ^ "No. 15669". The London Gazette. 24 January 1804. p. 111.

- ^ Boswall (1833), p. 210.

- ^ a b c The Diamond Rock Affair Genealogy of The Westcotts of Honiton

- ^ "Letter from Lieutenant Benjamin Westcott to parents, 1804". Afinitas.org. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ a b Rowbotham (1949).

- ^ Boswall (1833), pp. 212–3..

- ^ Aspinall (1969), p. 131.

- ^ Boswall (1833), p. 212.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 127.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 130.

- ^ L'affaire du Rocher du Diamant (31 mai – 2 juin 1805): "les Anglais considéraient le rocher comme un bâtiment de la Royal Navy. Dés lors, la tradition voulait qu'à chaque fois qu'un vaisseau britannique passe au large, il tire un coup de canon afin de saluer His Majesty's sloop-of-war Diamond Rock."

- ^ Byrne (1989), p. 101.

- ^ Boswall (1833), p. 214.

- ^ Boswall (1833), p. 215.

- ^ Byrne (1989), p. 180.

- ^ "Lieutenant Benjamin Westcott, 1804". Afinitas.org. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ "The Unsinkable HMS "Diamond Rock"". Maxingout.com. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ Boswall (1833), p. 213.

- ^ a b The Trafalgar Campaign: The Atlantic and the West Indies Rickard, J. Military History Encyclopedia on the Web

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 155.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 156.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 157.

- ^ a b Naval Chronicle, Vol. 15, pp.123–9.

- ^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 15, pp. 129–136.

- ^ Adkins & Adkins (2011), p. 158.

- ^ Marley (1997), pp. 366–7.

- ^ Adkins. The War for all the Oceans. p. 327.

- ^ Breen (1849), pp. 1–8.

- ^ The Island of Diamond Rock by Keyes. on Apple Music, 2024-01-17, retrieved 2024-04-19

- ^ Garesché (1902), p. 200.

- ^ Michel Brueil, L'herpertofaune de la réserve biologique domaniale de la Montagne Pelée, ONF Martinique, 1997, p. 22 Lire en ligne. Consulté le 8 juin 2008.

- ^ État des lieux publié par la DIREN, p. 6-10. Lire en ligne Archived 2008-11-23 at the Wayback Machine. Consulté le 8 juin 2008.

- ^ (in English) Fiche de la Couleuvre couresse sur iucnredlist.org. Consulté le 8 juin 2008.

- ^ "Diamond Rock (Le Rocher du Diamant)". Wondermondo. 21 December 2012.

- ^ "Diamond Rock". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Fine (2005), p. 75.

References

[edit]- Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (2011). The War For All The Oceans: From Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-4055-1343-2.

- Aspinall, Sir Algernon Edward (1969). West Indian tales of old. New York: Negro Universities Press.

- Boswall (1833). "Narrative of the Capture of the Diamond Rock, effected by Sir Samuel Hood, in the Centaur'". In Pollock, Arthur William Alsager (ed.). The United Service Magazine: With which are Incorporated the Army and Navy Magazine and Naval and Military Journal. Vol. Part 2. H. Colburn. pp. 210–215. (This article has a detailed account of the fortifying of the rock, and two diagrams showing the placement of the cannons, the batteries, and the mechanics of raising the cannons to the summit. The author is probably John Donaldson Boswall, who served in the cutting out expedition that captured Curieux, and went on to serve in her under George Edmund Byron Bettesworth).

- Breen, Henry Hegart (1849). The Diamond Rock, and Other Poems. William Pickering.

- Byrne, John D. (1989). Crime and punishment in the Royal Navy: discipline on the Leeward Islands station, 1784–1812. Aldershot, Hants, England: Scolar Press.

- Eckstein, John (1805) Picturesque Views of the Diamond Rock taken on the spot and dedicated to Sir Samuel Hood, K.B., Commodore and Commander in Chief of His Majesty's Ships and Vessels employed in the Windward and Leeward Charibbee Islands. (London: published for the author by J.C. Stadler).

- Fine, John Christopher (2005). Lost on the Ocean Floor: Diving the World's Ghost Ships. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press.

- Garesché, William A. (1902). Complete story of the Martinique and St. Vincent horrors. Chicago: L.G. Stahl.

- Marley, David (1997). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World from 1492 to the Present. London: ABC Clio.

- Southey, Thomas (1827) Chronological history of the West Indies. Vol. 3. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, & Green.

- Rowbotham, W.B. (1949). "The Diamond Rock". Naval Review. 37 (Nov. 4): 385–395.

- Stuart, Vivian & George T. Eggleston (1978). His Majesty's Sloop-of-war, Diamond Rock. London: Hale. ISBN 978-0709166924.