Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

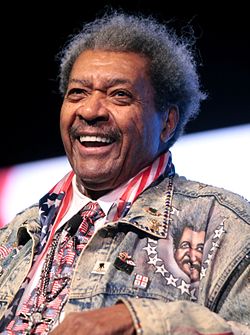

Don King

View on Wikipedia

Donald King (born August 20, 1931) is an American boxing promoter, known for his involvement in several historic boxing matchups.

Key Information

King's career highlights include, among multiple other enterprises, promoting "The Rumble in the Jungle" and the "Thrilla in Manila". King has promoted some of the most prominent names in boxing, including Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Tomasz Adamek, Roberto Duran, Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Chris Byrd, John Ruiz, Julio César Chávez, Ricardo Mayorga, Andrew Golota, Bernard Hopkins, Félix Trinidad, Roy Jones Jr., Azumah Nelson, Gerald McClellan, Marco Antonio Barrera, Salvador Sanchez, Wilfred Benitez, Wilfredo Gomez and Christy Martin. Many of these boxers sued him for allegedly defrauding them. Mike Tyson was quoted as saying, "He did more bad to black fighters than any white promoter ever in the history of boxing."[1]

King has been charged with killing two people in incidents 13 years apart. In 1954, King shot a man in the back after spotting him trying to rob one of his gambling houses; this incident was ruled a justifiable homicide.[2][1][3] In 1967, King was convicted of second-degree murder for stomping one of his employees to death because he owed him $600.[4] For this, he served three years and eleven months in prison, being released after the conviction was reduced to voluntary manslaughter on appeal.[5][6]

Early life

[edit]King was born in Cleveland, Ohio, as the fifth of six children to Clarence and Hattie King.[1][7] Clarence worked at the Otis Steel plant owned by the Jones & Laughlin company and was killed in a workplace accident on December 7, 1941, when a ladle exploded and engulfed him in molten steel. Hattie received $10,000 (equivalent to $213,778 in 2024) in compensation and relocated the family to the middle-class Mount Pleasant neighborhood. His mother made a living selling peanuts and homemade pies, helped by King and his younger sister and sold the wares at a local "policy house" that used the guise of a concession stand to run a numbers game. King and his older brothers all eventually became involved in the betting scheme, with King later stating "So now what we did is we capitalized off of this here, and we hustled. It was statutorily illegal, but who knew about the statutes?"[8][9] King graduated from John Adams High in 1951 and briefly attended Kent State University before dropping out.[10]

Bookmaking and killings

[edit]Beginning in 1951, King ran an illegal bookmaking operation out of the basement of a record store on Kinsman Road, earning the byname "The Kid", as well as the nicknames "Kingpin" and "the Numbers Czar".[9][11][12] During this time, King was charged with killing two men in incidents 13 years apart. On December 2, 1954, King fatally shot Hillary Brown in the back while he and two accomplices were attempting to rob one of King's gambling houses on East 123rd Street. This first killing was determined to be justifiable homicide.[13][14][15]

On April 20, 1966, King killed an employee, 34-year-old Sam Garrett, in an open street in front of several witnesses, for owing $600 in debt. King beat and kicked Garrett and held a .357 magnum revolver to his head; Garrett never regained consciousness and died of severe head trauma on April 24.[12][16] King claimed self-defense, while the prosecution, supported by witness testimony, including that of arresting police officer Bob Tonne, argued that Garrett was attacked by King, with Garrett's last words being quoted as "Don, I'll pay you the money."[12][17][18] He was convicted of second-degree murder for the second killing in 1967 and sentenced to one-to-twenty years imprisonment.[3][19] While he served his term at the Marion Correctional Institution,[20][21] he began self-education; according to his own words, he read everything in the prison library he could get his hands on.[22]

I learned this here, in the ... penitentiary, in reading everything that I can find my hands on, and didn't living the life that I live before I got to the penitentiary. That gave me an enlightenment on life that "don't get mad, get smart." That's why I want other kids to educate themselves, put it in their brain, they can't take that away.

In 1972 after serving three years and eleven months,[1] King was released when his attorney got the conviction reduced to manslaughter.[12] King was pardoned in 1983 by Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes, with letters from Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, George Voinovich, Art Modell, and Gabe Paul, among others, being written in support of King.[6]

Career

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

King entered the boxing world after persuading Muhammad Ali to box in a charity exhibition for a local hospital in Cleveland with the help of singer Lloyd Price. Early on, he formed a partnership with a local promoter named Don Elbaum, who already had a stable of fighters in Cleveland and years of experience in boxing. In 1974, King negotiated to promote a heavyweight championship fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire, popularly known as "The Rumble in the Jungle".[23] The fight between Ali and Foreman was a much-anticipated event. King's rivals all sought to promote the bout, but King was able to secure the then-record $10 million purse through an arrangement with the government of Zaire.

King arranged Ali's 1975 fight against journeyman Chuck Wepner.[24] It is widely believed the fight inspired Sylvester Stallone to write the screenplay for Rocky (1976).[25]

King solidified his position as one of boxing's preeminent promoters later that year with the third fight between Ali and Joe Frazier in Manila,[26] the capital of the Philippines, which King deemed the "Thrilla in Manila".[23] Aside from promoting the premier heavyweight fights of the 1970s, King was also busy expanding his boxing empire. Throughout the decade, he compiled an impressive roster of fighters, many of whom would finish their career with Hall of Fame credentials. Fighters including Larry Holmes, Wilfred Benítez, Roberto Durán, Salvador Sánchez, Wilfredo Gómez, and Alexis Argüello would all fight under the Don King Productions promotional banner in the 1970s.

For the next two decades, King continued to be among boxing's most successful promoters. Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Julio César Chávez, Aaron Pryor, Bernard Hopkins, Ricardo López, Félix Trinidad, Terry Norris, Carlos Zárate, Azumah Nelson, Andrew Gołota, Mike McCallum, Gerald McClellan, Meldrick Taylor, Marco Antonio Barrera, Tomasz Adamek, John Ruiz, and Ricardo Mayorga are some of the boxers who chose King to promote many of their biggest fights.[27]

Outside of boxing, he was the concert promoter for The Jacksons' 1984 Victory Tour.[28] In 1998, King purchased a Cleveland-based weekly newspaper serving the African American community in Ohio, the Call and Post, and as of 2011 continued as its publisher.[29][30]

King was elected to the Gaming Hall of Fame in 2008.[31]

In 2023, King was announced as the financier of the Bomaye Fight Club in Major League Wrestling.[32]

As of 2024, King still promoted world champions and was in talks with Canadian boxing promoter Dan Otter to stage a WBC cruiserweight world title bout sometime that year.[33][34]

Personal life

[edit]

Don King's wife, Henrietta, died on December 2, 2010, at the age of 87.[35] They had one biological daughter, Debbie, a son, Eric and adopted son Carl, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.[citation needed]

King is politically active and supported Barack Obama in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.[36] During the previous election, he had made media appearances promoting George W. Bush, which had included attendance at the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York City. He also has been a longtime supporter of Donald Trump.[37]

On June 10, 1987, King was made a 'Mason-at-Sight' by "Grand Master" Odes J. Kyle Jr. of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio, thereby making him a Prince Hall Freemason.[38][39] In the following year, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Humane letters degree from Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, by University President Dr. Arthur E. Thomas.[40]

King has conducted an annual turkey giveaway each Christmas for several years, in which he distributes two thousand free turkeys to needy South Floridians.[41]

In September 2024, King was hospitalized for an unspecified illness that required a blood transfusion.[42] Widespread concern for King's health was prompted by a Mike Tyson media interview where he said, "You know, Don is not doing well right now. He's probably close to 100 years old. He's not doing well."[43]

Lawsuits and prosecutions

[edit]King has been investigated for possible connections with organized crime. On May 20, 1957, the porch of King's house was bombed and in October of the same year, King was shot in the head and neck with a shotgun by unidentified gunmen, reportedly due to his refusal to pay $200 in monthly protection money to crime boss Shondor Birns. In December 1957, King's house was raided by the IRS for evasion of $32,029 (equivalent to $358,513 in 2024) in policy tax.[44] Charges of blackmail against Birns and five others were ultimately dropped in July 1958 when King declined to testify in court.[11][45] The attack on King's home eventually led to the landmark Supreme Court case Mapp v. Ohio. During a 1992 Senate investigation, King invoked the Fifth Amendment when questioned about his connection to mobster John Gotti.[46] When IBF president Robert W. Lee Sr. was indicted for racketeering in 1999, King was not indicted, nor did he testify at Lee's trial, though prosecutors reportedly "called him an unindicted co-conspirator who was the principal beneficiary of Lee's machinations."[47]

King has been involved in many fraud litigation cases with boxers. In 1982, he was sued by Muhammad Ali for underpaying him $1.1 million for a fight with Larry Holmes. King called in an old friend of Ali, Jeremiah Shabazz, and handed him a suitcase containing $50,000 in cash and a letter ending Ali's lawsuit against King. He asked Shabazz to visit Ali (who was in the hospital due to his failing health), get him to sign the letter, and then give Ali the $50,000. Ali signed it. The letter even gave King the right to promote any future Ali fights. According to Shabazz, "Ali was ailing by then and mumbling a lot. I guess he needed the money." Shabazz later regretted helping King. Ali's lawyer cried when he learned that Ali had ended the lawsuit without telling him.[48]

Larry Holmes has alleged that over the course of his career, King cheated him out of $10 million in fight purses, including claiming 25% of his purses as a hidden manager. Holmes says he received only $150,000 of a contracted $500,000 for his fight with Ken Norton, and $50,000 of $200,000 for facing Earnie Shavers, and claims King cut his purses for bouts with Muhammad Ali, Randall "Tex" Cobb, and Leon Spinks, underpaying him $2 million, $700,000, and $250,000, respectively. Holmes sued King over the accounting and auditing for the Gerry Cooney fight, charging that he was underpaid by $2 to $3 million.[49] Holmes sued King after King deducted a $300,000 'finder's fee' from his fight purse against Mike Tyson; Holmes settled for $150,000 and also signed a legal agreement pledging not to give any more negative information about King to reporters.[50]

Tim Witherspoon was threatened with being blackballed if he did not sign exclusive contracts with King and his stepson Carl. Not permitted to have his own lawyer present, he signed four "contracts of servitude" (according to Jack Newfield). One was an exclusive promotional contract with Don King, two were managerial contracts with Carl King, identical except one was "for show" that gave Carl King 33% of Witherspoon's purses and the other gave King a 50% share, more than is allowed by many boxing commissions. The fourth contract was completely blank.[51] Other examples include Witherspoon being promised $150,000 for his fight with Larry Holmes but receiving only $52,750. King's son Carl took 50% of Witherspoon's purse, illegal under Nevada rules, and the WBC sanctioning fee was also deducted from his purse.[52] He was forced to train at King's own training camp at Orwell, Ohio, instead of Ali's Deer Lake camp which Ali allowed Witherspoon to use for free. For his fight with Greg Page he received a net amount of $44,460 from his guaranteed purse of $250,000. King had deducted money for training expenses, sparring partners, fight and airplane tickets for his friends and family. Witherspoon was never paid a stipulated $100,000 for his training expenses and instead was billed $150 a day for using King's training camp. Carl King again received 50% of his purse, despite Don King Productions falsely claiming he had only been paid 33%.[53] HBO paid King $1,700,000 for Witherspoon to fight Frank Bruno. Witherspoon got a purse of $500,000 but received only $90,000 after King's deductions. Carl King received $275,000.[54] In 1987, Witherspoon sued King for $25 million in damages. He eventually settled for $1 million out of court.[55]

Former undisputed World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Mike Tyson has described King, his former promoter, as "ruthless", "deplorable", and "greedy".[56] In 1998, Tyson sued King for $100 million, alleging that the boxing promoter had cheated him out of millions over more than a decade.[57] The lawsuit was later settled out of court, with Tyson receiving $14 million.[58]

In 1996, Terry Norris sued King, alleging that King had stolen money from him and conspired with his manager to underpay him for fights. The case went to trial, but King settled out of court for $7.5 million in 2003. King also acceded to Norris's demand that the settlement be made public.[59][60]

In 2005, King launched a $2.5 billion defamation suit against the Walt Disney Pictures–owned ESPN, the makers of SportsCentury, after a documentary alleged that King had "killed, not once, but twice", threatened to break Larry Holmes' legs, had a hospital invest in a film that was never made, cheated Meldrick Taylor out of $1 million, and then threatened to have Taylor killed. Though the documentary repeated many claims that were already made, King said he had now had enough. King's attorney said "It was slanted to show Don in the worst way. It was one-sided from day one, Don is a strong man, but he has been hurt by this."[61] The case was dismissed on summary judgment with a finding that King could not show "actual malice" from the defendants, and that King had failed to prove that any of the challenged statements were false. The judgment also pointed out that the studio had tried on a number of occasions to interview King for the documentary, but he had declined; while not suggesting that King had a legal obligation to do so, the court sympathized with ESPN's circumstances on those grounds. King appealed the decision and three years later, the Second District Court of Appeals upheld the summary judgment, but disagreed with the original finding that none of the statements were false. In any case, Judge Dorian Damoorgian ruled, "Nothing in the record shows that ESPN purposefully made false statements about King in order to bolster the theme of the program or to inflict harm on King".[62]

In May 2003, King was sued by Lennox Lewis, who wanted $385 million from the promoter, claiming King used threats to pull Tyson away from a rematch with Lewis.[63]

In early 2006, Chris Byrd sued Don King for breach of contract, and the two eventually settled out of court under the condition that Byrd would be released from his contract with King.[64]

Media appearances

[edit]King appeared in the 2-part Miami Vice episode "Down for the Count" (season 3, episodes 12/13, 1987) as Mr. Cash.

King acted in a small role as more or less himself in The Last Fight (1982) and in the comedy Head Office (1985). He also had another brief cameo as himself in the film The Devil's Advocate (1997). He also appeared in a season 4 episode of Knight Rider, titled "Redemption of a Champion".

King made an appearance in the documentaries Beyond the Ropes (2008)[65] and Klitschko (2011).

King appeared in Moonlighting episode "Symphony in Knocked Flat" (season 3, episode 3, 1986) as himself & also made a brief cameo to the music video Liberian Girl by Michael Jackson filmed in April 1989 at A&M Chaplin Stage at A&M Studios in Los Angeles.

Media portrayals

[edit]As a character

[edit]- A puppet caricature of King appeared in a few episodes of the TV series DC Follies which ran from 1987 to 1989.

- In 1995, HBO aired Tyson, a television movie based upon the life of Mike Tyson, in which King was portrayed by actor Paul Winfield.

- In 1997, Ving Rhames played King in a television movie, Don King: Only in America, which aired on HBO.[66] Rhames won a Golden Globe Award for his portrayal of King.[67]

- In 1998, for the tenth episode of South Park's first season, "Damien", Jesus and Satan are pitted against one another in a boxing match to decide the conflict between good and evil; a character spoofing Don King appears, promoting Satan and the fight.

- In its first season, In Living Color featured a one-time sketch titled "King: The Early Years", set in a schoolyard in 1939, in which the narrator first leads viewers to believe that Martin Luther King Jr. got his start in childhood as a peacemaker between two fighting classmates – until "King" is revealed as a young Don King (portrayed by Damon Wayans), who promoted the schoolyard scuffle.

- In the episode "My Brother's Keeper" of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Carlton is portrayed as Don King in one of Will's dreams.

- In Celebrity Deathmatch, King's death was a running gag during the series' first season. In the final episode of the second season, he was matched against Donald Trump, with King being killed again, this time in the ring.[68]

- He was portrayed by Dave Chappelle in a skit about a "Gay America", as promoting a boxing match between two gay boxers.

- King helped create the video game Don King Presents: Prizefighter for the Xbox 360, which he promoted on IGN's podcast, Three Red Lights, and another called Don King Boxing for Wii and Nintendo DS.[69][70]

- King was featured in the 2001 film Ali, promoting the Rumble in the Jungle title fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. He was portrayed by Mykelti Williamson in the film.

Characters based on King

[edit]- The character of George Washington Duke, the flamboyant boxing promoter in the film Rocky V (1990), is modeled at least in part on Don King,[71] even using King's famous catchphrase "Only in America!"

- "The Homer They Fall", a 1996 episode in season 8 of the animated series The Simpsons, features a boxing promoter, Lucius Sweet (voiced by Paul Winfield), whose appearance is modeled on King, especially his hairstyle. In fact, Homer Simpson comments that Sweet is "exactly as rich and as famous as Don King, and he looks just like him, too!"

- The Great White Hype, a 1996 movie stars Rev. Fred Sultan (Samuel L. Jackson) as a manipulative boxing promoter.[72]

- In the 2005 Xbox video game Jade Empire, a character named Qui The Promoter is based on Don King, including personality and his speech patterns.

- In the 2016 indie video game Punch Club, a character named Ding Kong is modeled after King. In this game, Kong serves as the player's fight promoter in one of the conclusions of the game.[73]

Awards and honors

[edit]- 1997: International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee

- 2008: Gaming Hall of Fame inductee

- 2015: Street in Newark, New Jersey renamed Don King Way[74]

- 2016: Shaker Boulevard in Cleveland renamed Don King Way[75]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "ESPN Classic - Only in America". www.espn.com. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "From Hair To Eternity", December 10, 1990 - Franz Lidz, Sports Illustrated

- ^ a b Norris, Luke (December 31, 2020). "Never Forget Don King Killed 2 People (and Spent Less Than 4 Years in Prison) Before Becoming the Biggest Boxing Promoter in the World". Sportscasting | Pure Sports. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ Bonesteel, Matt. "Only in America! A Cleveland street where Don King killed someone might get renamed after him". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ Puma, Mike. "Only in America". ESPN Classic. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ a b "SPORTS PEOPLE; Don King Pardoned", The New York Times, January 5, 1983. Accessed May 29, 2011.

- ^ Iorfida, Chris (August 18, 2011). "Don King at 80: A wild ride". CBC Sports.

- ^ "KING or THE RING; Don King, a former numbers runner and convict (Murder 2) who quotes from Socrates and Galbraith, controls the heavyweight champ—and thus the game". The New York Times. September 28, 1975. pp. 19, 22. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Hauser, Thomas (February 1, 2000). The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing. University of Arkansas Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1557285973.

- ^ Williams, Bob. "Donald King's Mother Prays: God, Give Him Grace to Tell it all." Cleveland Call and Post, November 16, 1957, pg. 1.

- ^ a b Machado Zotti, Priscilla H. (January 31, 2005). Injustice for All: "Mapp vs. Ohio and the Fourth Amendment. Peter Lang Publishing Inc. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0820472676.

- ^ a b c d Donald, McRae (June 5, 2014). Dark Trade: Lost in Boxing. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 978-1471135385.

- ^ Kang, Jay Caspian (April 4, 2013). "The End and Don King". Grantland.

- ^ "Don King: Monarch of mayhem is loud and proud as lord of the rings". The Independent. March 8, 2009.

- ^ "Sports of The Times;'Trickeration' Trial Of Promoter Don King (Published 1995)". The New York Times. October 15, 1995. Archived from the original on June 19, 2024.

- ^ "Gambling Figure Dies Of Beating". Toledo Blade. April 25, 1966. p. 30.

- ^ Matthews, David (2000). Looking for a Fight. Headline. p. 131. ISBN 978-0747214397.

- ^ Newsfield, Jack (December 1, 2003). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. UNET 2 Corporation. p. 29. ISBN 978-0974020105.

- ^ "ESPN Classic - Only in America". www.espn.com. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ^ "Don King's Bouts Shift To Texas". The New York Times. March 27, 1977. p. 175.

- ^ "Sport: From Killer to King". Time. June 30, 1975.

- ^ METV Special Report Don King. Quote: "I learned this here, ... in the penitentiary, in reading everything that I can find my hands on, and didn't living the life that I live before I got to the penitentiary. That gave me an Enlightenment on life that don't get mad, get smart. That's why I want other kids to educate themselves, put it in their brain, they can't take that away."

- ^ a b Davies, Gareth A (August 24, 2008). "US Open: 'Apple Grapple' brings a gleam to Don King's eye. Don King, of the tall hair, celebrated his 77th birthday last week, dancing to the rhythm of a promotional pulse which shows no sign of abating". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Red (March 25, 1975). "But Wasn't It a Bleedin' Shame?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Child, Ben (February 23, 2016). "'Real-life Rocky' to sue over copycat film based on heavyweight contender's life". The Guardian. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). Only in America: The Life and Crimes of Don King (9780688101237): Jack Newfield: Books. William Morrow. ISBN 0688101232.

- ^ "54 Facts you probably don't know about Don King". Boxing News 24. January 14, 2008.

- ^ Connelly, Michael; Connelly, Christopher (March 15, 1984). "Michael Jackson: Trouble in Paradise?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History: Cleveland Call and Post". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "About Us". Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ "The Gaming Hall of Fame". University of Nevada, Las Vegas. February 12, 2009. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Pizzazz, Manolo Has (July 10, 2023). "Don King revealed as mystery money man in MLW". Cageside Seats. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Ringside (January 1, 2024). "Ryan Rozicki's promoter confirms WBC title talks with Don King". World Boxing News. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Hits, Random (December 5, 2023). "Ryan Rozicki Focused on WBC Title Showdown After Blasting Out Durodola". BoxingScene.com. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Rafael, Dan (December 3, 2010). "Don King's wife, Henrietta, dies at 87". ESPN. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ^ "Don King backs Obama for president, praises Bush". USA Today. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Strauss, Ben (July 14, 2017). "'Mr. President, You Know What It's Like To Be a Black Man'". Politico. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ 138th Proceedings of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio F&AM. Columbus: Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio. 1987. p. 20.

- ^ Gray, David (2012). The History of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio F&AM 1971–2011: The Fabric of Freemasonry. Columbus, Ohio: Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Ohio F&AM. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-615-63295-7. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ "Famed Promoter Don King Is Honored At Central State". Jet. Vol. 74. 1988. p. 2.

- ^ Scouten, Ted (December 16, 2011). "Don King's Turkey Giveaway Canceled After Truck 'Hijacked' « CBS Miami". Miami.cbslocal.com. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Larry (September 21, 2024). "Towering figure in boxing history dealing with health concerns". Yardbarker. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Mendez, Chris Malone (September 20, 2024). "Legendary Boxing Promoter Don King Is 'Not Doing Well' Amid Health Issues, Mike Tyson Says". Men's Journal. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ "Seize King Home In Cleveland For $32,000 Policy Tax". Jet. December 19, 1957. p. 47.

- ^ "Drop Charges Of Blackmail". Youngstown Vindicator. July 2, 1958. p. 10.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century, Volume 1, p. 99 (Oxford University Press, 2008).

- ^ CBS "Officials Want Promoters Out Of AC", CBSNews.com, October 5, 2000. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. pp. 162–4. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. pp. 147–8. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. pp. 216–7. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. pp. 221–2. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (1995). The Life and Crimes of Don King: The Shame of Boxing in America. William Morrow. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-9740201-0-5.

- ^ "Sports of The Times;'Trickeration' Trial Of Promoter Don King". The New York Times. October 15, 1995.

- ^ Tyson (film), 2008

- ^ "Mike Tyson files $100 million lawsuit against boxing promoter Don King". Jet. 1998. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012.

- ^ "NBC Sports". Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ "King to Pay $7.5 Million To Norris". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 11, 2003.

- ^ "Is King's Run as 'Teflon Don' Over?". Los Angeles Times. December 14, 2003.

- ^ "Promoter takes issue with SportsCentury piece". ESPN. ESPN.com news services. January 13, 2005. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (July 6, 2010). "ESPN scores TKO against Don King defamation lawsuit". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Springer, Steve (May 2003). "Lewis Sues Tyson and King Over No-Show at Stapled". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Neumeister, Larry (January 9, 2006). "Don King teams up with legal nemesis". USA Today. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Beyond the Ropes (Video 2008)". IMDb. October 14, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Don King: Only in America (TV Movie 1997)". IMDb. November 15, 1997. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Answers – The Most Trusted Place for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.com. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Celebrity Deathmatch". TV.com. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "2K". 2ksports.com. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "Don King Boxing (Wii)". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Iron Mike Gallego (May 14, 2014). "As long as boxing has Don King, it has an identity". Sports on Earth. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ Tucker, Ken. "The Great White Hype". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "References And Easter Eggs". Steam Community. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Carter, Barry (September 30, 2016). "Ding-Ding! 'Don King Way' may become permanent street name in Newark". NJ.com. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Kaily Cunningham (April 27, 2016). "Don King Way – Fox 8.com (WJW-TV)". Fox8.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2016.