Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kingdom of East Anglia

View on Wikipedia

The Kingdom of the East Angles,[1] informally known as the Kingdom of East Anglia, was a small independent kingdom of the Angles during the Anglo-Saxon period comprising what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens;[2] the area still known as East Anglia.

Key Information

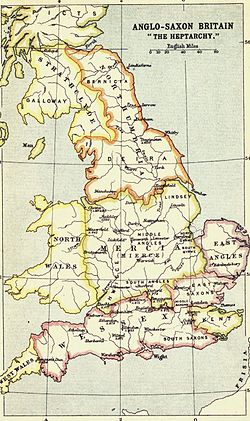

The kingdom formed in the 6th century in the wake of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and was one of the kingdoms of the Heptarchy. It was ruled by the Wuffingas dynasty in the 7th and 8th centuries, but the territory was taken by Offa of Mercia in 794. Mercian control lapsed briefly following the death of Offa but was reestablished. The Danish Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia in 865; after taking York it returned to East Anglia, killing King Edmund ("the Martyr") and making it Danish land in 869. After Alfred the Great forced a treaty with the Danes, East Anglia was left as part of the Danelaw.

It was taken back from Danish control by Edward the Elder and incorporated into the Kingdom of England in 918.

History

[edit]The Kingdom of East Anglia was organised in the first or second quarter of the 6th century, with Wehha listed as the first king of the East Angles, followed by Wuffa.[2] The Anglo-Saxon genealogy for East Angles gives Wehha as descended from Woden via Caesar.

Until 749 the kings of East Anglia were Wuffingas, named after the semi-historical Wuffa. During the early 7th century under Rædwald, East Anglia was a powerful Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Rædwald, the first East Anglian king to be baptised a Christian, is seen by many scholars to be the person buried within (or commemorated by) the ship burial at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge. During the decades that followed his death in about 624, East Anglia became increasingly dominated by the kingdom of Mercia. Several of Rædwald's successors were killed in battle, such as Sigeberht, under whose rule and with the guidance of his bishop, Felix of Burgundy, Christianity was firmly established.[citation needed]

From the death of Æthelberht II by the Mercians in 794 until 825, East Anglia ceased to be an independent kingdom, apart from a brief reassertion under Eadwald in 796. It survived until 869, when the Vikings defeated the East Anglians in battle and their king, Edmund the Martyr, was killed. After 879, the Vikings settled permanently in East Anglia. In 903 the exiled Æthelwold ætheling induced the East Anglian Danes to wage a disastrous war on his cousin Edward the Elder. By 918, after a succession of Danish defeats, East Anglia submitted to Edward and was incorporated into the Kingdom of England.

Settlement

[edit]East Anglia was settled by the Anglo-Saxons earlier than many other regions, possibly at the start of the 5th century.[3] It emerged from the political consolidation of the Angles in the approximate area of the former territory of the Iceni and the Roman civitas, with its centre at Venta Icenorum, close to Caistor St Edmund.[4] The region that was to become East Anglia seems to have been depopulated to some extent around the 4th century. Ken Dark writes that "in this area at least, and possibly more widely in eastern Britain, large tracts of land appear to have been deserted in the late 4th century, possibly including whole 'small towns' and villages. This does not seem to be a localised change in settlement location, size or character but genuine desertion."[5]

According to Bede, the East Angles (and the Middle Angles, Mercians and Northumbrians) were descended from natives of Angeln (now in modern Germany).[6] The first reference to the East Angles is from about 704–713, in the Whitby Life of St Gregory.[7] While the archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that a large-scale migration and settlement of the region by continental Germanic speakers occurred,[8] with a computer simulation showing that a migration of 250,000 people from Denmark to East Anglia could have been accomplished in 38 years with a reasonably small number of boats,[9] it has been questioned whether all of the migrants self-identified as Angles.[10][11]

The East Angles formed one of seven kingdoms known to post-medieval historians as the Heptarchy, a scheme used by Henry of Huntingdon in the 12th century. Some modern historians have questioned whether the seven ever existed contemporaneously and claim the political situation was far more complicated.[12]

Pagan rule

[edit]

The East Angles were initially ruled by the pagan Wuffingas dynasty, apparently named after an early king Wuffa, although his name may be a back-creation from the name of the dynasty, which means "descendants of the wolf".[4] An indispensable source on the early history of the kingdom and its rulers is Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People,[a] but he provided little on the chronology of the East Anglian kings or the length of their reigns.[14] Nothing is known of the earliest kings, or how the kingdom was organised, although a possible centre of royal power is the concentration of ship-burials at Snape and Sutton Hoo in eastern Suffolk. The "North Folk" and "South Folk" may have existed before the arrival of the first East Anglian kings.[15]

The most powerful of the Wuffingas kings was Rædwald, "son of Tytil, whose father was Wuffa",[4] according to the Ecclesiastical History. For a brief period in the early 7th century, whilst Rædwald ruled, East Anglia was among the most powerful kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England: he was described by Bede as the overlord of the kingdoms south of the Humber.[16] and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle identifies him as Bretwalda. In 616, he had been strong enough to defeat and kill the Northumbrian king Æthelfrith at the Battle of the River Idle and enthrone Edwin of Northumbria.[17] He was probably the individual honoured by the sumptuous ship burial at Sutton Hoo.[18] It has been suggested by Blair, on the strength of parallels between some objects found under Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo and those discovered at Vendel in Sweden, that the Wuffingas may have been descendants of an eastern Swedish royal family. However, the items previously thought to have come from Sweden are now believed to have been made in England, and it seems less likely that the Wuffingas were of Swedish origin.[15]

Christianisation

[edit]

Anglo-Saxon Christianity became established in the 7th century. The extent to which paganism was displaced is exemplified by a lack of any East Anglian settlement named after the old gods.[19]

In 604, Rædwald became the first East Anglian king to be baptised. He maintained a Christian altar, but at the same time continued to worship pagan gods.[20] From 616, when pagan monarchs briefly returned in Kent and Essex, East Anglia until Rædwald's death was the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom with a reigning baptised king. On his death in around 624, he was succeeded by his son Eorpwald, who was soon afterwards converted from paganism under the influence of Edwin,[4] but his new religion was evidently opposed in East Anglia and Eorpwald met his death at the hands of a pagan, Ricberht. After three years of apostasy, Christianity prevailed with the accession of Eorpwald's brother (or step-brother) Sigeberht, who had been baptised during his exile in Francia.[21] Sigeberht oversaw the establishment of the first East Anglian see for Felix of Burgundy at Dommoc, probably Dunwich.[22] He later abdicated in favour of his brother Ecgric and retired to a monastery.[23]

The three daughters of Anna of East Anglia, Æthelthryth, Wendreda, Seaxburh of Ely, are associated with the founding of abbeys.

Mercian aggression

[edit]The eminence of East Anglia under Rædwald fell victim to the rising power of Penda of Mercia and successors. From the mid-7th to early 9th centuries Mercian power grew, until a vast region from the Thames to the Humber, including East Anglia and the south-east, came under Mercian hegemony.[24] In the early 640s, Penda defeated and killed both Ecgric and Sigeberht,[20] who, having retired to religious life was later venerated as a saint.[25] Ecgric's successor Anna and Anna's son Jurmin were killed in 654 at the Battle of Bulcamp, near Blythburgh.[26] Freed from Anna's challenge, Penda subjected East Anglia to the Mercians.[27] In 655 Æthelhere of East Anglia joined Penda in a campaign against Oswiu that ended in a massive Mercian defeat at the Battle of the Winwaed, where Penda and his ally Æthelhere were killed.[28]

The last Wuffingas king was Ælfwald, who died in 749.[29] During the late 7th and 8th centuries East Anglia continued to be overshadowed by Mercian hegemony until, in 794, Offa of Mercia had the East Anglian king Æthelberht executed and then took control of the kingdom for himself.[30] A brief revival of East Anglian independence under Eadwald, after Offa's death in 796, was suppressed by the new Mercian king, Coenwulf.[31]

East Anglian independence was restored by a rebellion against Mercia led by Æthelstan in 825. Beornwulf of Mercia's attempt to restore Mercian control resulted in his defeat and death, and his successor Ludeca met the same end in 827. The East Angles appealed to Egbert of Wessex for protection against the Mercians and Æthelstan then acknowledged Egbert as his overlord. Whilst Wessex took control of the south-eastern kingdoms absorbed by Mercia in the 8th century, East Anglia could retain its independence.[32]

Viking attacks and eventual settlement

[edit]

In 865, East Anglia was invaded by the Danish Great Heathen Army, which occupied winter quarters and secured horses before departing for Northumbria.[33] The Danes returned in 869 to winter at Thetford, before being attacked by the forces of Edmund of East Anglia, who was defeated and killed at Hægelisdun[b] and then buried at Beodericsworth. Following his death Edmund became known as 'the Martyr' and venerated as patron saint and the town of Bury St Edmunds was established there.

From then on East Anglia effectively ceased to be an independent kingdom. Having defeated the East Angles, the Danes installed puppet-kings to govern on their behalf, while they resumed their campaigns against Mercia and Wessex.[36] In 878 the last active portion of the Great Heathen Army was defeated by Alfred the Great and withdrew from Wessex after making peace and agreeing that the Danes would treat the Christians equally. The treaty between Alfred and Guthrum acknowledged the latter's landholdings in East Anglia. In 880 the Vikings returned to East Anglia under Guthrum, who according to the medieval historian Pauline Stafford, "swiftly adapted to territorial kingship and its trappings, including the minting of coins."[37]

Along with the traditional territory of East Anglia, Cambridgeshire and parts of Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, Guthrum's kingdom probably included Essex, the one portion of Wessex to come under Danish control.[38] A peace treaty was made between Alfred and Guthrum sometime in the 880s.[39]

Under Scandinavian control, there are settlements in East Anglia which have names with Old Norse elements, e.g. '-thorp', '-by'

Absorption into the Kingdom of England

[edit]In the early 10th century, the East Anglian Danes came under increasing pressure from Edward, King of Wessex. In 901, Edward's cousin Æthelwold ætheling,[c] having been driven into exile after an unsuccessful bid for the throne, arrived in Essex after a stay in Northumbria. He was apparently accepted as king by some or all Danes in England and induced the East Anglian Danes to wage war on Edward in Mercia and Wessex. This ended in disaster with the death of Æthelwold and of Eohric of East Anglia in battle in December 902.[40]

From 911 to 917, Edward expanded his control over the rest of England south of the Humber, establishing in Essex and Mercia burhs, often designed to control the use of a river by the Danes.[41] In 917, the Danish position in the area suddenly collapsed. A rapid succession of defeats culminated in the loss of the territories of Northampton and Huntingdon, along with the rest of Essex: a Danish king, probably from East Anglia, was killed at Tempsford. Despite reinforcement from overseas, the Danish counter-attacks were crushed, and after the defection of many of their English subjects as Edward's army advanced, the Danes of East Anglia and of Cambridge capitulated.[42]

East Anglia was absorbed into the Kingdom of England in 918. Norfolk and Suffolk became part of a new earldom of East Anglia in 1017, when Thorkell the Tall was made earl by Cnut the Great.[43] The restored ecclesiastical structure saw two former East Anglian bishoprics (Elmham and Dunwich) replaced by a single one at North Elmham.[4]

Old East Anglian dialect

[edit]The East Angles spoke Old English. Their language is historically important, as they were among the first Germanic settlers to arrive in Britain during the 5th century: according to Kortmann and Schneider, East Anglia "can seriously claim to be the first place in the world where English was spoken."[44]

The evidence for dialects in Old English comes from the study of texts, place-names, personal names and coins.[45] A. H. Smith was the first to recognise the existence of a separate Old East Anglian dialect, in addition to the recognised dialects of Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon and Kentish. He acknowledged that his proposal for such a dialect was tentative, acknowledging that "the linguistic boundaries of the original dialects could not have enjoyed prolonged stability."[46] As no East Anglian manuscripts, Old English inscriptions or literary records such as charters have survived, there is little evidence to support the existence of such a dialect. According to a study by Von Feilitzen in the 1930s, the recording of many place-names in Domesday Book was "ultimately based on the evidence of local juries" and so the spoken form of Anglo-Saxon places and people was partly preserved in this way.[47] Evidence from Domesday Book and later sources suggests that a dialect boundary once existed, corresponding with a line that separates from their neighbours the English counties of Cambridgeshire (including the once sparsely-inhabited Fens), Norfolk and Suffolk.[48]

Geography

[edit]

The kingdom of the East Angles bordered the North Sea to the north and the east, with the River Stour historically dividing it from the East Saxons to the south. The North Sea provided a "thriving maritime link to Scandinavia and the northern reaches of Germany", according to the historian Richard Hoggett. The port of Ipswich (Gipeswic) was established in 7th century.

The kingdom's western boundary varied from the rivers Ouse, Lark and Kennett to further westwards, as far as the Cam in what is now Cambridgeshire. At its greatest extent, the kingdom comprised the modern-day counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and parts of eastern Cambridgeshire.[49]

Erosion on the eastern border and deposition on the north coast altered the East Anglian coastline in Roman and Anglo-Saxon times (and continues to do so). In the latter, the sea flooded the low-lying Fens. As sea levels fell alluvium was deposited near major river estuaries and the "Great Estuary" (which the Saxon Shore forts at Burgh Castle and Caister had guarded) became closed off by a large spit of land.[50]

Sources

[edit]No East Anglian charters (and few other documents) have survived, while the medieval chronicles that refer to the East Angles are treated with great caution by scholars. So few records from the Kingdom of the East Angles have survived because of a complete destruction of the kingdom's monasteries and disappearance of the two East Anglian sees as a result of Viking raids and settlement.[51] The main documentary source for the early period is Bede's 8th-century Ecclesiastical History of the English People. East Anglia is first mentioned as a distinct political unit in the Tribal Hidage, thought to have been compiled somewhere in England during the 7th century.[52]

Anglo-Saxon sources that include information about the East Angles or events relating to the kingdom:[53]

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

- The Tribal Hidage, where the East Angles are assessed at 30,000 hides, evidently superior in resources to lesser kingdoms such as Sussex and Lindsey.[54]

- Historia Brittonum

- Life of Foillan, written in the 7th century

Post-Norman sources (of variable historical validity):

- The 12th century Liber Eliensis

- Florence of Worcester's Chronicle, written in the 12th century

- Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum, written in the 12th century

- Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum, written in the 13th century

List of monarchs

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See Hoggett, 2010, pp. 24–27, for a detailed discussion of Bede's original sources and an account of the events in East Anglia that he refers to in the Ecclesiastical History.[13]

- ^ identified variously as Bradfield St Clare in 983, Hellesdon in Norfolk (documented as Hægelisdun c. 985) or Hoxne in Suffolk,[34] and now with Maldon in Essex.[4][29][35]

- ^ Ætheling was a title for a prince of the royal family who was eligible to become king

References

[edit]- ^ (Old English: Ēastengla Rīċe; Latin: Regnum Orientalium Anglorum)

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "East Anglia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Catherine Hills, The Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain: an archaeological perspective (2016)

- ^ a b c d e f Higham, N. J. (1999). "East Anglia, Kingdom of". In M. Lapidge; et al. (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Blackwell. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- ^ Dark, Ken R. "Large-scale population movements into and from Britain south of Hadrian's Wall in the 4th to 6th centuries AD" (PDF).

- ^ Warner, 1996, p. 61.

- ^ Kirby, p. 20.

- ^ Coates, Richard (1 May 2017), "Celtic whispers: revisiting the problems of the relation between Brittonic and Old English", Namenkundliche Informationen, German Society for Name Research: 147–173, doi:10.58938/ni576, ISSN 0943-0849

- ^ Härke, Heinrich (2011). "Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis". Medieval Archaeology. 55 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1179/174581711X13103897378311. S2CID 162331501.

- ^ Toby F. Martin, The Cruciform Brooch and Anglo-Saxon England, Boydell and Brewer Press (2015), pp. 174-178

- ^ Hills, Catherine (2015), "The Anglo-Saxon Migration: An Archaeological Case Study of Disruption", in Baker, Brenda J.; Tsuda, Takeyuki (eds.), Migrations and Disruptions, University Press of Florida, pp. 45–48, doi:10.2307/j.ctvx0703w, JSTOR j.ctvx0703w

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Hoggett, East Anglian Conversion, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Yorke, 2002, p. 58.

- ^ a b Yorke, 2002, p. 61.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 54.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 52.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 55.

- ^ Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 24, p. 68.

- ^ a b Yorke, 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Warner, 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Warner, 1996, p. 84.

- ^ Brown and Farr, 2001, pp. 2 and 4.

- ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1897). The Lives of the Saints. Vol. 12. p. 712 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Warner, The Origins of Suffolk, p. 142.

- ^ Yorke, 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Volume 6, p. 328.

- ^ Brown and Farr, 2001, p. 215.

- ^ Brown and Farr, 2001, p. 310.

- ^ Brown and Farr, 2001, pp. 222 and 313.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 173.

- ^ "Edmund of East Anglia Part 5 – The Last Mystery: Where Did Edmund Die?". Hidden East Anglia. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Briggs, Keith (2011). "Was Hægelisdun in Essex? A new site for the martyrdom of Edmund". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. XLII: 277–291.

- ^ Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard D.; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- ^ Stafford, A Companion to the early Middle Ages, p. 205.

- ^ Hunter Blair, Peter; Keynes, Simon (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-521-29219-1.

- ^ Lavelle, Ryan (2010). Alfred's wars: sources and interpretations of Anglo-Saxon warfare in the Viking Age. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-84383-569-1.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Wilson, David Mackenzie (1976). The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. pp. 135–6. ISBN 978-0-416-15090-2.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 328.

- ^ Harper-Bill, Christopher; Van Houts, Elisabeth (2002). A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84383-341-3.

- ^ Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: a Multimedia Reference Tool. Vol. 1 Phonology. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

- ^ Fisiak, 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Fisiak, 2001, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Fisiak, 2001, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Fisiak, 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Hoggett, 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Hoggett, 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 58.

- ^ Carver, The Age of Sutton Hoo, p. 3.

- ^ Carver, Age of Sutton Hoo, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Kirby, 2000, p. 11.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (2001). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London, New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Carver, M. O. H., ed. (1992). The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-Western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-361-2.

- Fisiak, Jacek (2001). "Old East Anglian: a problem in Old English dialectology". In Fisiak, Jacek; Trudgill, Peter (eds.). East Anglian English. Boydell and Brewer. doi:10.1017/9781846150678. ISBN 978-1-84615-067-8.

- Hadley, Dawn (2009). "Viking Raids and Conquest". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c. 500–c. 1100. Chichester: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0628-3.

- Hoggett, Richard (2010). The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-595-0.

- Hoops, Johannes (1986) [1911–1919]. Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde [Encyclopedia of Germanic Antiquity] (in German). Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-010468-4.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0.

- Stenton, Sir Frank (1988) [1943]. Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821716-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3.

- Warner, Peter (1996). The Origins of Suffolk. Origins of the Shire. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3817-4.

- Williams, Gareth (2001). "Mercian Coinage and Authority". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Grossi, Joseph (2021). Angles on a Kingdom: East Anglian Identities from Bede to Ælfric. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-14875-0-573-8.

- Metcalf, D. M. (2000). "Determining the mint-attribution of East Anglian Sceattas through regression analysis" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 70: 1–11.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1972). "The pre-Viking age church in East Anglia". Anglo-Saxon England. 1. Cambridge University Press: 1–22. doi:10.1017/S0263675100000053. JSTOR 44510584. S2CID 161209303.

Kingdom of East Anglia

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Early Development

Anglo-Saxon Settlement and Tribal Consolidation

Following the Roman withdrawal from Britain around 410 AD, Angle settlers from regions in northern Germany and southern Denmark, particularly the Angeln area, began migrating to the eastern territories now encompassing Norfolk and Suffolk. Archaeological evidence from 5th- and 6th-century burial sites, such as those at Spong Hill in Norfolk and early cemeteries in Suffolk, reveals cremation and inhumation practices with continental-style grave goods, including brooches and weapons, indicating direct cultural importation rather than gradual diffusion. Place-name evidence further supports this, with the majority of Norfolk and Suffolk toponyms deriving from Old English elements like "-ham" (homestead) and "-inga" (people of), reflecting Angle linguistic dominance and replacement of fewer than a dozen surviving Celtic names in the region.[11][1][12] Genetic and isotopic analyses corroborate substantial population movement, with ancient DNA from East Anglian sites showing up to 76% continental northern European ancestry in early medieval individuals, challenging models of minimal migration and elite dominance in favor of broader demographic replacement of Romano-British populations. Strontium and oxygen isotope ratios in tooth enamel from early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, such as Oakington in Cambridgeshire near East Anglia's bounds, identify non-local origins in 25-40% of sampled individuals, pointing to migrants from the North Sea coastal zones. This influx likely displaced or assimilated indigenous groups, as evidenced by the sharp decline in Roman-style villa occupation and the emergence of new settlement patterns by the mid-5th century.[13][14][15] Settlement consolidated into tribal groupings known as the North Folk in Norfolk and South Folk in Suffolk, organized around kinship and warrior elites rather than centralized kingship, as inferred from dispersed farmstead clusters and weapon-inclusive burials denoting status hierarchies. Excavations at sites like West Stow in Suffolk uncover early 5th-6th century farmsteads with sunken-featured buildings, timber halls, and evidence of mixed arable-pastoral economies suited to the region's fertile loams and coastal marshes. Pollen records from East Anglian peat bogs indicate shifts toward increased pastoralism and woodland clearance post-400 AD, aligning with immigrant agricultural practices and the exploitation of fens for grazing and resources, facilitated by maritime access for initial arrivals and trade. Tribal cohesion emerged through shared Germanic customs and elite patronage, setting the stage for later political unification without early evidence of overarching authority.[16][17][11]Emergence of Kingship and Earliest Rulers

The emergence of kingship in East Anglia during the 6th century marked a shift from dispersed tribal leadership among Anglo-Saxon settlers to more centralized authority, as reflected in the royal genealogies preserved in later Anglian collections. These genealogies trace the origins of the Wuffingas dynasty to Wehha, a figure active in the mid-6th century, who is named as the progenitor without direct contemporary evidence but positioned as the initial ruler consolidating control over the East Angles.[3] Wehha's successor, Wuffa, from whom the dynasty derives its name meaning "wolf kin," is similarly semi-historical, with king-lists suggesting his reign around 571, representing the foundational claim to patrilineal descent that later kings invoked to legitimize their rule.[1] This dynastic narrative, compiled in 9th-century manuscripts like those in the Anglian collection, underscores pragmatic kin-based alliances essential for coordinating defense and tribute extraction amid rival kingdoms.[18] The Tribal Hidage, a Mercian-era document assessing tribute obligations, estimates the East Angles' territory at 30,000 hides, indicating substantial land under proto-monarchical oversight by the late 7th century and implying earlier unification of sub-groups like the North Folk and South Folk into a single polity under figures like Wehha.[19] This hidage figure, representing taxable units rather than precise population, highlights the kingdom's scale relative to neighbors, with East Anglia's assessment exceeding that of smaller entities like the East Saxons at 7,000 hides, facilitating the ruler's ability to mobilize resources for warfare and alliances.[19] Such consolidation likely arose from necessity, as fragmented tribal structures proved vulnerable to incursions from Britons or neighboring Germanic groups, prompting the adoption of hereditary kingship to ensure continuity in leadership and loyalty networks. Early indicators of centralized power include the development of royal vills—fortified estate centers serving administrative and symbolic functions—though archaeological traces from the 6th century remain elusive, with firmer evidence appearing in the subsequent Wuffingas reigns. Patrilineal succession, as enshrined in the genealogies, prioritized male heirs within the kin-group to maintain stability, reflecting causal adaptations to the competitive landscape rather than ideological constructs, and avoiding diffusion of authority through elective or egalitarian means that could invite internal strife.[3] These structures laid the groundwork for the kingdom's expansion, enabling rulers to project power beyond mere tribal defense toward regional hegemony in the early 7th century.Political History

Pagan Period and Internal Consolidation

Rædwald, king of East Anglia from around 599 to circa 624, played a pivotal role in the kingdom's internal consolidation during the early 7th century by leveraging military victories to assert regional dominance. In circa 616, he led East Anglian forces to victory over Northumbrian king Æthelfrith at the Battle of the River Idle in present-day Nottinghamshire, where Æthelfrith was killed and his sons fled, allowing Rædwald to install the exiled Edwin as Northumbrian ruler under East Anglian overlordship.[20][21] This triumph, which reportedly cost the life of Rædwald's son Rægenshere, elevated East Anglia's status among Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, enabling tribute extraction and establishing Rædwald as a bretwalda, or paramount ruler, over southern England.[22] Pagan religious practices reinforced warrior cohesion under royal sponsorship, as evidenced by elaborate barrow burials containing grave goods symbolizing status and martial prowess. The Sutton Hoo ship burial, dated to the early 7th century and provisionally associated with Rædwald, yielded a wealth of artifacts including a ceremonial helmet, shield, sword, and garnet-inlaid jewelry, arranged to convey the deceased's authority and provisions for an afterlife journey, consistent with pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon funerary rites.[23] Excavations near Rendlesham have uncovered a 7th-century structure interpreted as a possible pagan temple or cult house, aligning with historical accounts of royal centers hosting rituals to ancestral deities for societal unity.[24] Economic consolidation stemmed from East Anglia's strategic control of North Sea trade routes linking to continental emporia, fostering wealth accumulation through imports and local production. Grave goods at Sutton Hoo included Byzantine silverware, Swedish gold bracteates, and 37 Merovingian gold tremisses, indicating direct exchange networks with Francia and Scandinavia that bypassed intermediaries and supported military endeavors without reliance on later institutional frameworks.[23]Christianization and Ecclesiastical Foundations

The Christianization of the Kingdom of East Anglia proceeded primarily through royal initiative in the mid-7th century, driven by alliances with Christian kingdoms like Kent and Northumbria rather than widespread popular conversion. King Sigeberht, who had been baptized during exile in Kent, invited the Burgundian bishop Felix around 630 to evangelize his realm, establishing the first bishopric at Dommoc (likely near modern Dunwich or Felixstowe) as a base for missionary work among the pagan Angles.[5] This elite-led effort aligned East Anglia with broader Christian networks, facilitating diplomatic ties and access to literate clergy for governance, though hagiographic accounts in Bede's Ecclesiastical History emphasize Felix's miracles over empirical conversion rates.[25] Sigeberht's successor, Anna (r. c. 640–654), further patronized Irish missionary Fursey, who arrived circa 633 and founded a monastery at Cnobheresburg (modern Burgh Castle) with royal support, converting local elites and establishing monastic communities that served as administrative outposts.[26] Fursey's efforts, documented in his vita, focused on preaching and ascetic discipline, yielding verifiable foundations like the Burgh site, but relied on Anna's protection amid persistent pagan resistance; Anna's death in battle against Mercian pagans in 654 underscored the precariousness of top-down adoption without full military dominance.[27] By 673, Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury reorganized the East Anglian church, splitting the single see into two: Dommoc for the south and North Elmham for the north, enhancing ecclesiastical control and literacy through scriptoria that preserved charters and aided royal record-keeping.[28] Tensions with expansionist Mercia later highlighted the church's role in stabilizing state power, as seen in the 794 martyrdoms of East Anglian kings Æthelred and Æthelberht, beheaded on orders from Offa of Mercia during a failed marriage alliance.[29] These executions, recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle without motive but linked in later passiones to Offa's dynastic ambitions, did not reverse Christian integration; instead, Æthelberht's prompt local veneration and burial at Hereford integrated martyrdom narratives into East Anglian identity, reinforcing church loyalty to offset Mercian overlordship.[30] Church foundations empirically advanced administration by introducing monastic education, where clergy trained in Latin facilitated legal documentation and diplomacy, though without evidence of transformative pacifism—kings like Anna continued warfare post-conversion.[31]Conflicts with Mercia and Regional Power Dynamics

During the mid-8th century, King Beonna of East Anglia (r. c. 749–760) issued a distinctive coinage featuring his name and title "rex," marking a temporary assertion of royal autonomy amid growing Mercian dominance. This numismatic independence, including reformed silver pennies modeled after Northumbrian styles, suggests East Anglia briefly escaped direct subjugation, though likely through tribute payments to Mercia to avert invasion, as evidenced by the kingdom's subordinate position in regional power structures.[32] Beonna's reign ended around 760, coinciding with Mercian King Offa's consolidation of midland resources, which enabled sustained military campaigns against peripheral kingdoms.[33] Offa's expansionist policies from the 760s onward systematically eroded East Anglian sovereignty, culminating in direct conquest by the 780s.[34] Mercian forces imposed control through overstriking East Anglian coin dies with Offa's name and imagery, symbolizing economic subordination and the redirection of minting authority to serve Mercian interests.[32] Charters from Offa's reign, while sparse for East Anglia due to limited ecclesiastical preservation, reflect Mercian oversight of land grants and ecclesiastical appointments, effectively integrating the region into Mercia's administrative orbit.[25] The 794 execution of East Anglian King Æthelberht II, ordered by Offa at Sutton Walls, exemplified this brutal realism, eliminating potential resistance and affirming Mercian hegemony; Æthelberht's beheading, possibly motivated by alliance intrigues with Wessex, prompted no effective retaliation due to East Anglia's military disparities.[33][35] These conflicts underscored causal imbalances rooted in resource and terrain asymmetries: Mercia's populous heartlands and fortified core supported larger levies and sustained logistics, overwhelming East Anglia's agrarian base, while the latter's expansive fens and flat lowlands offered scant natural defenses against incursions, facilitating rapid Mercian advances absent chokepoints like hills or rivers.[1] East Anglian resistance proved futile against such structural vulnerabilities, with subjugation manifesting not as mutual rivalry but as unidirectional expansionism driven by Offa's strategic imperatives, unmitigated by contemporary narratives of balanced heptarchic competition.[33] By Offa's death in 796, East Anglia functioned as a Mercian dependency, its kingship hollowed and regional autonomy curtailed until transient revival under Coenwulf's weaker successors.[1]Viking Invasions, Resistance, and Subjugation

The Great Heathen Army, a coalition of Norse warriors, arrived in England in 865 and established winter quarters in East Anglia, marking the onset of sustained Viking campaigns against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.[36] This strategic overwintering allowed the invaders to replenish supplies from local resources while exploiting the fragmented defenses of the region, as East Anglian forces lacked the unity to mount an effective coordinated response.[37] After subduing Northumbria in 866–867, the army returned to East Anglia in 869, overran the kingdom, and killed King Edmund, whose death underscored the East Anglians' military disorganization against the Vikings' superior mobility and numbers.[36] Edmund's demise, dated to 869 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, involved his capture and execution for refusing to submit to pagan overlords; contemporary hagiographer Abbo of Fleury detailed how the king was bound to a tree, scourged, shot with arrows until resembling a "hideous hedgehog," and finally beheaded after defying demands to renounce Christianity. [36] This martyrdom symbolized the collapse of native royal authority, with no significant recorded resistance from successors, as the Vikings imposed settlement and control, integrating East Anglia into the emerging Danelaw territories under Danish legal customs.[38] The kingdom's fall stemmed from internal divisions and inadequate fortifications, contrasting with the invaders' logistical advantages, including ship-based reinforcements and winter campaigning that disrupted Anglo-Saxon harvest cycles.[39] Following Alfred the Great's victory at Edington in 878, Viking forces under Guthrum relocated to East Anglia, where he assumed kingship around 880 and ruled until 890, adopting the Christian name Æthelstan to legitimize governance. Guthrum's administration maintained continuity by issuing silver pennies in the Anglo-Saxon style, blending Scandinavian oversight with existing minting practices to stabilize the economy amid subjugation, as evidenced by coins bearing his name from probable East Anglian or London workshops. [40] This monetary reform facilitated Danish settlement without total disruption, though it reinforced the Danelaw's imposition, dividing land among warriors and enforcing Norse law over former East Anglian holdings.[38] Sporadic resistance, such as local skirmishes, proved futile against the entrenched Viking presence, sealing the kingdom's absorption into Scandinavian-dominated regions by the late ninth century.[39]Integration into Unified England

Following the coordinated offensive launched in 917 by Edward the Elder, King of the Anglo-Saxons, and his sister Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, the Danish forces in East Anglia submitted to Edward after the construction of strategic fortresses at sites including Towcester and Wigingamere, alongside broader campaigning that secured control over eastern territories.[41] This military reabsorption ended the semi-independent Danish rule established after the Great Heathen Army's conquest in 869, with East Anglia's armies of Northampton, Cambridge, and East Anglia itself pledging allegiance, reflecting a pragmatic consolidation driven by Wessex's need to neutralize persistent Viking threats rather than ideological unification.[42] Upon Æthelflæd's death on 12 June 918, Edward assumed direct overlordship of Mercia and completed the incorporation of East Anglia by late 918 or early 919, expelling remaining Danish elements and redistributing lands through grants to loyal thegns, as evidenced by surviving charters confirming Wessex-style tenurial arrangements in former East Anglian territories.[42] Coinage provides numismatic corroboration: the anonymous "St. Edmund" penny series, minted primarily at Thetford and Ipswich under Danish rule from circa 890, persisted briefly post-conquest before transitioning to regal issues bearing Edward's name or bust, signaling the cessation of local symbolic autonomy and alignment with Wessex minting standards by the early 920s. Administrative integration preserved East Anglia's pre-existing shires of Norfolk and Suffolk, which were subdivided into hundreds for fiscal and judicial purposes, adapting Alfred the Great's burh-based defensive network—originally Wessex-centric—to the region through refortification of sites like Thetford and incorporation of Danish-era strongholds into a unified system of mutual support against raids.[38] Edward extended burh construction into frontier zones adjacent to East Anglia, such as Buckingham and Maldon, to anchor control, fostering economic continuity via trade routes while subordinating local elites to ealdormen appointed from Wessex.[43] Under Æthelstan (r. 924–939), who inherited this expanded domain, East Anglia functioned as an eastern buffer province governed by appointed ealdormen, with military campaigns focused northward but leveraging the region's ports and flatlands for rapid deployment against residual Scandinavian incursions, solidifying its role in a causally defensive reconfiguration of English power rather than mere territorial accretion.[44] This phase emphasized evidentiary land grants and fiscal assessments over royal titles specific to East Anglia, marking the kingdom's effective dissolution into the emergent English state by the mid-10th century.[42]Government and Rulers

Structure of Monarchy and Succession Practices

The monarchy of East Anglia operated within a framework typical of Anglo-Saxon kingships, where authority derived from a combination of dynastic descent and endorsement by assemblies of ealdormen, thegns, and ecclesiastical leaders, functioning as a proto-witan to confer legitimacy on claimants. Hereditary succession predominated within the Wuffingas dynasty from the late sixth century onward, with kings tracing lineage to the semi-legendary Wuffa, but claims were frequently contested through military demonstrations of prowess, as rival kin or external powers like Mercia intervened in transitions. Unlike later medieval emphases on divine right or strict primogeniture, East Anglian kingship prioritized the ruler's role as a war-leader capable of protecting the realm and distributing patronage, including appointments to comital offices that oversaw shire administration, judicial functions, and fyrd mobilization.[3][1] Royal governance involved itinerant oversight of territories, with kings traveling between vills such as Rendlesham—identified by Bede as a primary seat—and other estates to hold assemblies, dispense justice, and collect renders, as evidenced by archaeological remains of multiple high-status halls and artifact scatters indicating periodic royal presence rather than fixed residence. Surviving charters, though scarce for East Anglia compared to Wessex or Mercia, reference such mobility in land grants witnessed at varied locations, underscoring the decentralized nature of control over core regions like the Norfolk and Suffolk folklands. Kings rewarded loyalty by alienating bookland to followers, but ultimate authority rested on maintaining martial coalitions, with ealdormen serving as deputies who enforced royal edicts and led regional defenses.[45][46] Dynastic continuity faced rupture after the martyrdom of King Edmund in 869, when no direct Wuffingas heir consolidated power amid Viking conquest, leading to a break in native succession and the imposition of Danish kingship under figures like Guthrum, who adapted local structures by integrating Scandinavian military hierarchies while retaining Anglo-Saxon administrative elements like shire-based governance. This period highlighted the monarchy's pragmatic flexibility, as subsequent English overlords from Wessex reasserted control by 918 through appointed ealdormen rather than reviving the old dynasty, prioritizing stable integration over genealogical purity. Such breaks underscored that legitimacy hinged on effective defense and alliance-building over unyielding heredity, with assemblies playing a key role in transitions even under foreign influence.[3][47]List of Kings and Notable Reigns

The recorded kings of East Anglia derive mainly from Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (completed c. 731), entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (compiled from the 9th century onward), and surviving coinage, which provide numismatic evidence for later rulers amid chronological gaps. The Wuffingas dynasty, named after the eponymous Wuffa, dominated from the late 6th to mid-8th century, with succession often marked by kin-strife evidenced by short reigns and depositions. Archaeological finds, such as those at Sutton Hoo, corroborate the status of certain kings like Rædwald but do not resolve all regnal uncertainties.[1][5]| King | Reign (approximate) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wehha | Mid-6th century (d. c. 571) | Earliest attested ruler; pagan king during initial Anglo-Saxon consolidation in the region; father of Wuffa; no specific achievements recorded, but his rule marks the foundation of monarchical tradition per later genealogies.[1] |

| Wuffa | c. 571–578 | Son of Wehha; eponym of the Wuffingas dynasty; limited details, but his reign reflects tribal unification without noted expansions or conflicts.[1] |

| Tytila | c. 578–616 | Son of Wuffa; father of Rædwald; unremarkable reign with no major events attested in primary sources.[48] |

| Rædwald | c. 599/616–624/627 | Son of Tytila; achieved temporary hegemony as a bretwalda (overlord) among Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, evidenced by his victory over Northumbrian king Æthelfrith c. 616, which installed Edwin of Deira; converted to Christianity c. 605 but retained pagan practices; associated with the Sutton Hoo ship burial (c. 625), indicating high wealth and status; death led to succession disputes.[5][48] |

| Eorpwald | c. 627 | Son of Rædwald; brief reign ended by assassination; baptized under Northumbrian influence, marking early Christian adoption; short duration suggests instability from rival claimants.[48] |

| Ricberht | c. 627 | Possible usurper or short-term successor to Eorpwald; reign of under one year per Bede, highlighting kin-strife and vulnerability to external pressures; no surviving achievements.[1] |

| Sigeberht | c. 630–c. 640 | Co-ruled initially with Ecgric; abdicated to pursue monastic life after baptism by Northumbrian missionaries; his flight during Mercian invasion c. 640 exposed military weaknesses, leading to defeat and death of Ecgric.[1] |

| Anna | c. 640–654 | Brother of Eni; multiple short intervals of rule amid depositions; father of several East Anglian kings; killed in Mercian conflicts, underscoring repeated subjugation to Mercia; supported church foundations but failed to prevent territorial losses.[48] |

| Æthelhere | 654–655 | Brother of Anna; allied with Penda of Mercia but died at Winwæd; brief tenure reflects dependence on external powers.[1] |

| Æthelwald | c. 654–664 | Son of Æthelric; extended reign but overshadowed by Mercian dominance; no major independent successes recorded.[1] |

| Ealdwulf | 664–713 | Son of Æthelric; longest reign (49 years), providing stability; supported synod at Hatfield (680) but maintained pagan elements; death marked end of direct Wuffingas male line continuity. |

| Ælfwald | 713–749 | Son or kinsman of Ealdwulf; last Wuffingas king; promoted minsters and literacy, per charters; peaceful but subordinate to Mercia; coins attest rule, but no expansions.[49] |

| Beonna | c. 749–760 | Post-Wuffingas; known from coins indicating independent minting; short reign amid Mercian overlordship; limited records suggest internal consolidation failures.[32] |

| Æthelberht II | c. 760–794 | Killed by Offa of Mercia c. 794, per Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; attempted independence led to execution, evidencing subjugation; coins confirm rule.[32] |

| Edmund | c. 855–869 | Last independent native king; ascended young (c. 14); refused submission to Great Heathen Army, leading to capture and execution on 20 November 869, as recorded in Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; defiance preserved in hagiographic accounts but resulted in Viking conquest without military success.[50] |

Society and Economy

Social Structure and Daily Life

Anglo-Saxon society in the Kingdom of East Anglia exhibited a rigid hierarchy, with the king supported by elite thegns who held hereditary bookland grants conferring privileges over estates and dependents.[52] Below them ranked ceorls, freeborn peasants organized in vill communities who cultivated communal fields, rendered labor services, and participated in the local fyrd militia.[52] At the base were slaves, known as theows, comprising war captives from inter-kingdom conflicts and debtors, who performed menial tasks without legal rights.[53] Daily life for the majority ceorls centered on agrarian routines, involving seasonal ploughing with ard tools, sowing crops like barley and emmer wheat, and herding livestock in open fields delineated by place-names such as -ham (homestead) and -tun (farmstead) across East Anglian landscapes.[54] Archaeological evidence from rural sites reveals iron sickles, querns for grinding grain, and weaving tools, underscoring a subsistence economy tied to the land's fertility.[55] Burial practices highlighted gender-differentiated roles, with female graves frequently containing brooches, beads, and girdle-hangers symbolizing household management and textile production, while male interments featured knives or tools indicative of provisioning duties.[56] Such distinctions in East Anglian cemeteries, including those near Sutton Hoo, reflect customary divisions rather than fluid identities, with women's jewelry denoting status through marital and familial ties.[57] Dispute resolution relied on kinship networks, where extended families enforced wergild payments for offenses like homicide, drawing from Germanic customary law that prioritized collective liability over individual adjudication.[58] In East Anglia, lacking codified provincial laws, these practices mirrored broader Anglo-Saxon norms, fostering social cohesion through oaths and blood-feud settlements among ceorls and thegns alike.[59]Agricultural Base, Trade, and Material Wealth

The agricultural economy of the Kingdom of East Anglia centered on arable cultivation suited to the region's light, sandy soils, which supported the growth of wheat and barley as primary crops. Archaeobotanical evidence from sites such as West Stow in Suffolk reveals carbonized grains and crop weed seeds indicative of winter-sown wheat and spring-sown barley, integrated with early forms of communal field management precursors to later open-field systems.[60] Marginal fenland areas, spanning parts of Norfolk and Suffolk, contributed limited arable output but served for seasonal grazing and resource extraction like reeds and fish, with settlement patterns reflecting adaptation to wetland conditions rather than extensive drainage until later medieval periods.[61][62] Animal husbandry complemented arable farming, with faunal assemblages from Middle Saxon sites like West Stow and Ipswich demonstrating a shift toward sheep dominance for wool, meat, and manure, alongside cattle for draft power and dairy, and pigs for opportunistic foraging. Analysis of bone remains indicates kill-off patterns optimized for sustained production, with sheep comprising up to 50% or more of livestock in early Anglo-Saxon contexts, reflecting self-sufficiency in protein and traction needs.[16][63][64] Trade networks, facilitated by coastal access and emporia like Ipswich, involved export of local pottery and import of continental goods, evidenced by the widespread distribution of Ipswich ware—a gritty, wheel-turned pottery mass-produced from circa 680 to 870 AD and found across East Anglia and in Frisian contexts. Quern-stones of Rhineland lava, used for grinding grain, appear in archaeological deposits, pointing to exchanges with Gaul and Frisia, while silver sceattas minted in East Anglia circulated in North Sea trade routes by the 7th-8th centuries.[65][66][67] Material wealth accumulated unevenly, concentrating in royal and elite hands as seen in the 7th-century Sutton Hoo ship burial, which contained over 200 gold and garnet artifacts, Byzantine silver, and Swedish cloisonné, valued at equivalents of thousands of shillings and signaling tribute extraction, gifting, and prestige economies rather than broad commercial prosperity. Such treasures, including the iconic belt buckle, underscore incentives for loyalty among warriors and kin, derived from agricultural surpluses and intermittent trade rather than industrialized output.[23][68][69]Religion and Culture

Pre-Christian Beliefs and Practices

The ruling Wuffingas dynasty of East Anglia traced its lineage to Woden, the paramount Germanic deity associated with war, wisdom, and kingship, as recorded in early medieval genealogies such as those derived from the Historia Brittonum.[3] This mythical descent underscored Woden's centrality in East Anglian cosmology, positioning rulers as divinely sanctioned figures whose authority derived from ancestral ties to the god, thereby integrating religious reverence with monarchical legitimacy to maintain social order among warrior elites.[3] Elite burials, exemplified by the early 7th-century Sutton Hoo ship burial, incorporated extensive grave goods including swords, helmets, shields, and garnet-inlaid artifacts, indicating beliefs in a postmortem existence where the deceased retained martial prowess and status.[23] Weapons positioned deliberately around the burial chamber—such as a sword on the right side and helmet near the head—reflect ritual preparations for an afterlife analogous to warrior paradises in broader Germanic traditions, equipping the dead for perpetual conflict or divine assembly.[23] Associated interments at Sutton Hoo reveal ritual violence, with multiple bodies showing decapitation, binding, and contorted poses—such as folded or spread-eagled forms—consistent with human sacrifices to accompany principal burials or appease supernatural forces.[70] These practices, centered on monumental ship mounds and potentially sacred natural sites, functioned to perpetuate hierarchical structures by dramatizing the king's semi-divine role and the perils of the otherworld, compelling loyalty through awe-inspiring displays of power and continuity beyond death.[70]Christian Institutions and Monastic Influence

The Christian diocese of East Anglia was established in the mid-7th century under Bishop Felix, a Burgundian missionary consecrated around 631 by Archbishop Honorius of Canterbury and dispatched to the kingdom at the invitation of King Sigeberht I, who had converted during exile in Kent. Felix, operating from a base at Dunwich, structured the episcopal see to oversee evangelization and ecclesiastical administration across the East Anglian territories, founding churches and at least one monastery, such as at Soham, which supported local governance through literate clergy capable of documenting royal decrees and alliances. This diocesan framework mirrored the kingdom-based organization of the Anglo-Saxon church, where bishops served dual roles in spiritual oversight and secular diplomacy, enabling kings to leverage ecclesiastical networks for legitimacy and intertribal relations without reliance on Roman imperial precedents.[25][71] Monastic foundations further entrenched Christianity's practical utility, providing centers for scriptoria that preserved Latin literacy amid a largely oral Germanic culture, thus facilitating the drafting of charters for land transactions and oaths that stabilized royal authority. The monastery at Ely, initially established around 633 under Sigeberht's patronage and later refounded as a double house by Queen Æthelthryth in 673, exemplified this role, managing estates that buffered economic disruptions and trained clerics for diplomatic envoys to neighboring kingdoms like Kent and Northumbria. Similarly, early monastic sites in Suffolk, evolving into the community at Bury (Beodricsworth), offered repositories for records and relics, enhancing the kingdom's administrative resilience before Viking incursions fragmented these institutions.[25][72] After the Great Heathen Army's conquest in 869 and the execution of King Edmund, his veneration as a martyr-king crystallized into a cult that symbolized defiance against Danish overlordship, with his relics—initially buried at Sutton and translated to Bury around 903—drawing endowments that rebuilt ecclesiastical infrastructure during recovery under West Saxon hegemony. This cult, evidenced by coinage bearing Edmund's legend from the late 9th century, promoted regional cohesion by framing resistance as a Christian imperative, aiding diplomacy with Alfred's successors who restored East Anglian sees to counter pagan relapse.[73][74] Surviving post-conquest charters, though sparse due to Viking depredations, record royal confirmations of church lands, such as those under King Edgar in the 960s, which allocated estates to monasteries like Ely and Bury to incentivize loyalty and agrarian restoration, thereby integrating clerical influence into the territorial stabilization that preceded full incorporation into unified England. These grants underscored the church's causal role in recovery, as monastic demesnes provided fixed assets for reconstruction, independent of volatile lay tenures disrupted by warfare.[75][25]Language, Artifacts, and Archaeological Evidence

The Old English spoken in the Kingdom of East Anglia belonged to the Anglian branch of dialects, distinct from the West Saxon variety that predominated in later literary records. Direct textual evidence is limited, primarily consisting of place-names featuring elements like -inga denoting tribal or kin-group settlements, charters from religious houses such as Bury St Edmunds, and scattered glosses that align with broader Anglian phonological and morphological traits, including variations in vowel reflexes and verb forms not fully palatalized as in West Saxon.[76] These sources indicate a dialect shaped by migration from northern Germania, with sparse but consistent markers of regional divergence observable in onomastic data.[77] Archaeological finds illuminate the material culture supporting linguistic inferences of a cohesive Anglian identity. The Sutton Hoo ship burial, radiocarbon dated to around 625 CE and linked to King Rædwald through its scale and grave goods, yielded a face-mask helmet, shoulder-clasps, and a purse lid inlaid with garnets and cloisonné work, reflecting technical expertise and stylistic parallels to Swedish Vendel-period artifacts and continental Migration-era metalwork.[23] [68] The garnets, imported via long-distance trade networks possibly extending to the Mediterranean, underscore elite access to exotic materials and cultural exchanges with Gothic and Byzantine influences.[68] Excavations at Rendlesham, a site identified by Bede as a royal vills, have recently transformed understandings of early elite infrastructure. Publications from 2021–2023 digs, detailed in 2024 analyses, uncovered a sprawling settlement complex active from the 5th to 8th centuries, featuring a large timber hall, craft workshops, and a possible pre-Christian temple structure akin to Scandinavian cult buildings, yielding over 5,000 artifacts including high-status metalwork and ceramics.[78] [79] This evidence revises prior models positing delayed kingship consolidation, demonstrating sustained royal presence and economic centrality from migration-era phases onward, with material continuity linking to Sutton Hoo's sophistication.[45] [80]Geography and Territories

Core Regions and Boundaries

The Kingdom of East Anglia's core territory centered on the lands of the North Folk and South Folk, encompassing areas that provided a cohesive agricultural and settlement base amid low-lying plains and river valleys.[81] This heartland, assessed at 30,000 hides in the late seventh-century Tribal Hidage—a Mercian tribute document enumerating subject peoples' fiscal capacities—reflected substantial resources relative to smaller kingdoms like Sussex at 7,000 hides.[19] [82] The hidage figure underscores the kingdom's extent beyond mere tribal cores, incorporating fringes toward Essex under certain rulers, though fluid alliances often dictated effective control rather than fixed lines.[1] Natural features defined defensible boundaries, with the expansive Fens to the west and north serving as marshy barriers that deterred large-scale incursions from Mercian forces.[81] These wetlands, intersected by Roman-era roads like the Fen Causeway, limited access while enabling localized defenses, prioritizing environmental obstacles over expansive territorial claims. Southern limits aligned roughly with river estuaries such as the Stour and Orwell, transitioning into Essex territories sometimes under East Anglian influence.[1] Eastern seaboard exposure to North Sea raids reinforced reliance on internal cohesion rather than linear fortifications. Territorial shifts occurred amid external pressures, notably Mercian conquests from the mid-seventh century onward, evidenced by linear earthworks like the Devil's Dyke and Fleam Dyke—Anglo-Saxon constructions spanning Cambridgeshire into Suffolk to check western advances.[83] These remnants, up to 10 meters high and ditched on the eastern side, indicate adaptive boundary reinforcement during periods of subjugation, such as under Penda of Mercia around 630 or Offa in the late eighth century. Viking incursions from 865 further contracted the realm, reducing it to fragmented holdings by 878, with fenland refuges providing temporary havens amid collapsing frontiers.[1]Key Settlements and Strategic Sites

Ipswich developed as a key trading hub during the Middle Saxon period, with archaeological evidence including the production of distinctive Ipswich ware pottery dated to circa 650–850 AD and a mint that struck silver sceattas around 730–750 AD.[84][85] Thetford functioned as a prominent Late Saxon urban center, hosting a mint and serving as the East Anglian bishopric seat from 1071 to 1095, with earlier roots as a potential royal or ecclesiastical estate repurposed after Viking wintering there in 869–870 AD.[86][87] North Elmham held strategic ecclesiastical importance as the primary seat of the Bishops of East Anglia in the late Saxon era, anchoring a major episcopal estate; excavations have uncovered foundations of an Anglo-Saxon timber cathedral predating the Norman chapel on the site.[88][89] Rendlesham operated as a royal vill and site for assemblies, evidenced by geophysical surveys and excavations from 2015 onward revealing a large timber hall, high-status artifacts, and structures spanning the 6th to 7th centuries AD, positioning it as a core power center adjacent to the Sutton Hoo ship burial.[90][78] In the wake of Viking incursions, post-Alfredian defensive adaptations included burhs in East Anglia, such as fortified elements at Thetford, which evolved into Anglo-Danish strongholds blending Wessex-inspired earthwork ramparts with Viking military practices for regional control.[86][91]