Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Event camera

View on Wikipedia

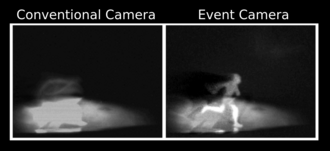

An event camera, also known as a neuromorphic camera,[1] silicon retina,[2] or dynamic vision sensor,[3] is an imaging sensor that responds to local changes in brightness. Event cameras do not capture images using a shutter as conventional (frame) cameras do. Instead, each pixel inside an event camera operates independently and asynchronously, reporting changes in brightness as they occur, and staying silent otherwise.

Functional description

[edit]Event camera pixels independently respond to changes in brightness as they occur.[4] Each pixel stores a reference brightness level, and continuously compares it to the current brightness level. If the difference in brightness exceeds a threshold, that pixel resets its reference level and generates an event: a discrete packet that contains the pixel address and timestamp. Events may also contain the polarity (increase or decrease) of a brightness change, or an instantaneous measurement of the illumination level,[5] depending on the specific sensor model. Thus, event cameras output an asynchronous stream of events triggered by changes in scene illumination.

Event cameras typically report timestamps with a microsecond temporal resolution, 120 dB dynamic range, and less under/overexposure and motion blur[4][6] than frame cameras. This allows them to track object and camera movement (optical flow) more accurately. They yield grey-scale information. Initially (2014), resolution was limited to 100 pixels.[citation needed] A later entry reached 640x480 resolution in 2019.[citation needed] Because individual pixels fire independently, event cameras appear suitable for integration with asynchronous computing architectures such as neuromorphic computing. Pixel independence allows these cameras to cope with scenes with brightly and dimly lit regions without having to average across them.[7] It is important to note that, while the camera reports events with microsecond resolution, the actual temporal resolution (or, alternatively, the bandwidth for sensing) is on the order of tens of microseconds to a few milliseconds, depending on signal contrast, lighting conditions, and sensor design.[8]

| Sensor | Dynamic

range (dB) |

Equivalent

framerate (fps) |

Spatial

resolution (MP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human eye | 30–40 | 200-300* | - |

| High-end DSLR camera (Nikon D850) | 44.6[9] | 120 | 2–8 |

| Ultrahigh-speed camera (Phantom v2640)[10] | 64 | 12,500 | 0.3–4 |

| Event camera[11] | 120 | 50,000 – 300,000** | 0.1–1 |

* Indicates human perception temporal resolution, including cognitive processing time. **Refers to change recognition rates, and varies according to signal and sensor model.

Types

[edit]Temporal contrast sensors (such as DVS[4] (Dynamic Vision Sensor), or sDVS[12] (sensitive-DVS)) produce events that indicate polarity (increase or decrease in brightness), while temporal image sensors[5] indicate the instantaneous intensity with each event. The DAVIS[13] (Dynamic and Active-pixel Vision Sensor) contains a global shutter active pixel sensor (APS) in addition to the dynamic vision sensor (DVS) that shares the same photosensor array. Thus, it has the ability to produce image frames alongside events. The CSDVS (Center Surround Dynamic Vision Sensor) adds a resistive center surround network to connect adjacent DVS pixels.[14][15] This center surround implements a spatial high-pass filter to further reduce output redundancy. Many event cameras additionally carry an inertial measurement unit (IMU).

Retinomorphic sensors

[edit]

Another class of event sensors are so-called retinomorphic sensors. While the term retinomorphic has been used to describe event sensors generally,[16][17] in 2020 it was adopted as the name for a specific sensor design based on a resistor and photosensitive capacitor in series.[18] These capacitors are distinct from photocapacitors, which are used to store solar energy,[19] and are instead designed to change capacitance under illumination. They (dis)charge slightly when the capacitance is changed, but otherwise remain in equilibrium. When a photosensitive capacitor is placed in series with a resistor, and an input voltage is applied across the circuit, the result is a sensor that outputs a voltage when the light intensity changes, but otherwise does not.

Unlike other event sensors (typically a photodiode and some other circuit elements), these sensors produce the signal inherently. They can hence be considered a single device that produces the same result as a small circuit in other event cameras. Retinomorphic sensors have to-date[as of?] only been studied in a research environment.[20][21][22][23]

Algorithms

[edit]

Image reconstruction

[edit]Image reconstruction from events has the potential to create images and video with high dynamic range, high temporal resolution, and reduced motion blur. Image reconstruction can be achieved using temporal smoothing, e.g. high-pass or complementary filter.[24] Alternative methods include optimization[25] and gradient estimation[26] followed by Poisson integration. It has been also shown that the image of a static scene can also be recovered from noise events only by analyzing their correlation with scene brightness.[27]

Spatial convolutions

[edit]The concept of spatial event-driven convolution was postulated in 1999[28] (before the DVS), but later generalized during EU project CAVIAR[29] (during which the DVS was invented) by projecting event-by-event an arbitrary convolution kernel around the event coordinate in an array of integrate-and-fire pixels.[30] Extension to multi-kernel event-driven convolutions[31] allows for event-driven deep convolutional neural networks.[32]

Motion detection and tracking

[edit]Segmentation and detection of moving objects viewed by an event camera can seem to be a trivial task, as it is done by the sensor on-chip. However, these tasks are difficult, because events carry little information[33] and do not contain useful visual features like texture and color.[34] These tasks become even more challenging given a moving camera,[33] because events are triggered everywhere on the image plane, produced by moving objects and the static scene (whose apparent motion is induced by the camera's ego-motion). Some of the recent[when?] approaches to solving this problem include the incorporation of motion-compensation models[35][36] and traditional clustering algorithms.[37][38][34][39]

Potential applications

[edit]Potential applications include most tasks classically fitting conventional cameras, but with emphasis on machine vision tasks (such as object recognition, autonomous vehicles, and robotics.[22]). The US military is[as of?] considering infrared and other event cameras because of their lower power consumption and reduced heat generation.[7]

Considering the advantages the event camera possesses, compared to conventional image sensors, it is considered fitting for applications requiring low power consumption and latency, and where it is difficult to stabilize the camera's line of sight. These applications include the aforementioned autonomous systems, but also space imaging, security, defense, and industrial monitoring. Research into color sensing with event cameras is[when?] underway,[40] but it is not yet[when?] convenient for use with applications requiring color sensing.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Li, Hongmin; Liu, Hanchao; Ji, Xiangyang; Li, Guoqi; Shi, Luping (2017). "CIFAR10-DVS: An Event-Stream Dataset for Object Classification". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 11 309. doi:10.3389/fnins.2017.00309. ISSN 1662-453X. PMC 5447775. PMID 28611582.

- ^ Sarmadi, Hamid; Muñoz-Salinas, Rafael; Olivares-Mendez, Miguel A.; Medina-Carnicer, Rafael (2021). "Detection of Binary Square Fiducial Markers Using an Event Camera". IEEE Access. 9: 27813–27826. arXiv:2012.06516. Bibcode:2021IEEEA...927813S. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3058423. ISSN 2169-3536. S2CID 228375825.

- ^ Liu, Min; Delbruck, Tobi (May 2017). "Block-matching optical flow for dynamic vision sensors: Algorithm and FPGA implementation". 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS). pp. 1–4. arXiv:1706.05415. doi:10.1109/ISCAS.2017.8050295. ISBN 978-1-4673-6853-7. S2CID 2283149.

- ^ a b c Lichtsteiner, P.; Posch, C.; Delbruck, T. (February 2008). "A 128×128 120 dB 15μs Latency Asynchronous Temporal Contrast Vision Sensor" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 43 (2): 566–576. Bibcode:2008IJSSC..43..566L. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2007.914337. ISSN 0018-9200. S2CID 6119048. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-03. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b Posch, C.; Matolin, D.; Wohlgenannt, R. (January 2011). "A QVGA 143 dB Dynamic Range Frame-Free PWM Image Sensor With Lossless Pixel-Level Video Compression and Time-Domain CDS". IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 46 (1): 259–275. Bibcode:2011IJSSC..46..259P. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2010.2085952. ISSN 0018-9200. S2CID 21317717.

- ^ Longinotti, Luca. "Product Specifications". iniVation. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- ^ a b "A new type of camera". The Economist. 2022-01-29. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ Hu, Yuhuang; Liu, Shih-Chii; Delbruck, Tobi (2021-04-19). "v2e: From Video Frames to Realistic DVS Events". arXiv:2006.07722 [cs.CV].

- ^ DxO. "Nikon D850: Tests and Reviews | DxOMark". www.dxomark.com. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ "Phantom v2640". www.phantomhighspeed.com. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ Longinotti, Luca. "Product Specifications". iniVation. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- ^ Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Linares-Barranco, B. (March 2013). "A 128x128 1.5% Contrast Sensitivity 0.9% FPN 3μs Latency 4mW Asynchronous Frame-Free Dynamic Vision Sensor Using Transimpedance Amplifiers" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 48 (3): 827–838. Bibcode:2013IJSSC..48..827S. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2012.2230553. ISSN 0018-9200. S2CID 6686013.

- ^ Brandli, C.; Berner, R.; Yang, M.; Liu, S.; Delbruck, T. (October 2014). "A 240 × 180 130 dB 3 µs Latency Global Shutter Spatiotemporal Vision Sensor". IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 49 (10): 2333–2341. Bibcode:2014IJSSC..49.2333B. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2014.2342715. ISSN 0018-9200.

- ^ Delbruck, Tobi; Li, Chenghan; Graca, Rui; Mcreynolds, Brian (October 2022). "Utility and Feasibility of a Center Surround Event Camera". 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). pp. 381–385. doi:10.1109/ICIP46576.2022.9897354. ISBN 978-1-6654-9620-9.

- ^ Di Girolamo, Arturo; Metzner, Christian; Urhan, Özcan (May 2025). "An Event-Based Line Sensor with Configurable Antagonistic Center Surround". 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS). pp. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ISCAS56072.2025.11043186. ISBN 979-8-3503-5683-0.

- ^ Boahen, K. (1996). "Retinomorphic vision systems". Proceedings of Fifth International Conference on Microelectronics for Neural Networks. pp. 2–14. doi:10.1109/MNNFS.1996.493766. ISBN 0-8186-7373-7. S2CID 62609792.

- ^ Posch, Christoph; Serrano-Gotarredona, Teresa; Linares-Barranco, Bernabe; Delbruck, Tobi (2014). "Retinomorphic Event-Based Vision Sensors: Bioinspired Cameras With Spiking Output". Proceedings of the IEEE. 102 (10): 1470–1484. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2014.2346153. hdl:11441/102353. ISSN 1558-2256. S2CID 11513955.

- ^ Trujillo Herrera, Cinthya; Labram, John G. (2020-12-07). "A perovskite retinomorphic sensor". Applied Physics Letters. 117 (23): 233501. Bibcode:2020ApPhL.117w3501T. doi:10.1063/5.0030097. ISSN 0003-6951. S2CID 230546095.

- ^ Miyasaka, Tsutomu; Murakami, Takurou N. (2004-10-25). "The photocapacitor: An efficient self-charging capacitor for direct storage of solar energy". Applied Physics Letters. 85 (17): 3932–3934. Bibcode:2004ApPhL..85.3932M. doi:10.1063/1.1810630. ISSN 0003-6951.

- ^ "Perovskite sensor sees more like the human eye". Physics World. 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Simple Eyelike Sensors Could Make AI Systems More Efficient". Inside Science. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ a b Hambling, David. "AI vision could be improved with sensors that mimic human eyes". New Scientist. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "An eye for an AI: Optic device mimics human retina". BBC Science Focus Magazine. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ a b Scheerlinck, Cedric; Barnes, Nick; Mahony, Robert (2019). "Continuous-Time Intensity Estimation Using Event Cameras". Computer Vision – ACCV 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11365. Springer International Publishing. pp. 308–324. arXiv:1811.00386. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-20873-8_20. ISBN 978-3-030-20873-8. S2CID 53182986.

- ^ Pan, Liyuan; Scheerlinck, Cedric; Yu, Xin; Hartley, Richard; Liu, Miaomiao; Dai, Yuchao (June 2019). "Bringing a Blurry Frame Alive at High Frame-Rate With an Event Camera". 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Long Beach, CA, USA: IEEE. pp. 6813–6822. arXiv:1811.10180. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00698. ISBN 978-1-7281-3293-8. S2CID 53749928.

- ^ Scheerlinck, Cedric; Barnes, Nick; Mahony, Robert (April 2019). "Asynchronous Spatial Image Convolutions for Event Cameras". IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters. 4 (2): 816–822. arXiv:1812.00438. Bibcode:2019IRAL....4..816S. doi:10.1109/LRA.2019.2893427. ISSN 2377-3766. S2CID 59619729.

- ^ Cao, Ruiming; Galor, Dekel; Kohli, Amit; Yates, Jacob L.; Waller, Laura (20 January 2025). "Noise2Image: noise-enabled static scene recovery for event cameras". Optica. 12 (1): 46. arXiv:2404.01298. Bibcode:2025Optic..12...46C. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.538916.

- ^ Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Andreou, A.; Linares-Barranco, B. (Sep 1999). "AER Image Filtering Architecture for Vision Processing Systems". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Fundamental Theory and Applications. 46 (9): 1064–1071. doi:10.1109/81.788808. hdl:11441/76405. ISSN 1057-7122.

- ^ Serrano-Gotarredona, R.; et, al (Sep 2009). "CAVIAR: A 45k-Neuron, 5M-Synapse, 12G-connects/sec AER Hardware Sensory-Processing-Learning-Actuating System for High Speed Visual Object Recognition and Tracking". IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks. 20 (9): 1417–1438. Bibcode:2009ITNN...20.1417S. doi:10.1109/TNN.2009.2023653. hdl:10261/86527. ISSN 1045-9227. PMID 19635693. S2CID 6537174.

- ^ Serrano-Gotarredona, R.; Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Acosta-Jimenez, A.; Linares-Barranco, B. (Dec 2006). "A Neuromorphic Cortical-Layer Microchip for Spike-Based Event Processing Vision Systems". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers. 53 (12): 2548–2566. Bibcode:2006ITCSR..53.2548S. doi:10.1109/TCSI.2006.883843. hdl:10261/7823. ISSN 1549-8328. S2CID 8287877.

- ^ Camuñas-Mesa, L.; et, al (Feb 2012). "An Event-Driven Multi-Kernel Convolution Processor Module for Event-Driven Vision Sensors". IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits. 47 (2): 504–517. Bibcode:2012IJSSC..47..504C. doi:10.1109/JSSC.2011.2167409. hdl:11441/93004. ISSN 0018-9200. S2CID 23238741.

- ^ Pérez-Carrasco, J.A.; Zhao, B.; Serrano, C.; Acha, B.; Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Chen, S.; Linares-Barranco, B. (November 2013). "Mapping from Frame-Driven to Frame-Free Event-Driven Vision Systems by Low-Rate Rate-Coding and Coincidence Processing. Application to Feed-Forward ConvNets". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 35 (11): 2706–2719. Bibcode:2013ITPAM..35.2706P. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2013.71. hdl:11441/79657. ISSN 0162-8828. PMID 24051730. S2CID 170040.

- ^ a b Gallego, Guillermo; Delbruck, Tobi; Orchard, Garrick Michael; Bartolozzi, Chiara; Taba, Brian; Censi, Andrea; Leutenegger, Stefan; Davison, Andrew; Conradt, Jorg; Daniilidis, Kostas; Scaramuzza, Davide (2020). "Event-based Vision: A Survey". IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. PP (1): 154–180. arXiv:1904.08405. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3008413. ISSN 1939-3539. PMID 32750812. S2CID 234740723.

- ^ a b Mondal, Anindya; R, Shashant; Giraldo, Jhony H.; Bouwmans, Thierry; Chowdhury, Ananda S. (2021). "Moving Object Detection for Event-based Vision using Graph Spectral Clustering". 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW). pp. 876–884. arXiv:2109.14979. doi:10.1109/ICCVW54120.2021.00103. ISBN 978-1-6654-0191-3. S2CID 238227007 – via IEEE Xplore.

- ^ Mitrokhin, Anton; Fermuller, Cornelia; Parameshwara, Chethan; Aloimonos, Yiannis (October 2018). "Event-Based Moving Object Detection and Tracking". 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Madrid: IEEE. pp. 1–9. arXiv:1803.04523. doi:10.1109/IROS.2018.8593805. ISBN 978-1-5386-8094-0. S2CID 3845250.

- ^ Stoffregen, Timo; Gallego, Guillermo; Drummond, Tom; Kleeman, Lindsay; Scaramuzza, Davide (2019). "Event-Based Motion Segmentation by Motion Compensation". 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). pp. 7244–7253. arXiv:1904.01293. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00734. ISBN 978-1-7281-4803-8. S2CID 91183976.

- ^ Piątkowska, Ewa; Belbachir, Ahmed Nabil; Schraml, Stephan; Gelautz, Margrit (June 2012). "Spatiotemporal multiple persons tracking using Dynamic Vision Sensor". 2012 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. pp. 35–40. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2012.6238892. ISBN 978-1-4673-1612-5. S2CID 310741.

- ^ Chen, Guang; Cao, Hu; Aafaque, Muhammad; Chen, Jieneng; Ye, Canbo; Röhrbein, Florian; Conradt, Jörg; Chen, Kai; Bing, Zhenshan; Liu, Xingbo; Hinz, Gereon (2018-12-02). "Neuromorphic Vision Based Multivehicle Detection and Tracking for Intelligent Transportation System". Journal of Advanced Transportation. 2018 e4815383. doi:10.1155/2018/4815383. ISSN 0197-6729.

- ^ Mondal, Anindya; Das, Mayukhmali (2021-11-08). "Moving Object Detection for Event-based Vision using k-means Clustering". 2021 IEEE 8th Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON). pp. 1–6. arXiv:2109.01879. doi:10.1109/UPCON52273.2021.9667636. ISBN 978-1-6654-0962-9. S2CID 237420620.

- ^ "CED: Color Event Camera Dataset". rpg.ifi.uzh.ch. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

Event camera

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Basic Principles

An event camera is a neuromorphic imaging sensor that asynchronously records per-pixel brightness changes rather than capturing full frames at fixed intervals. Unlike traditional cameras, it outputs a stream of discrete events triggered only by significant local intensity variations, enabling high temporal resolution and low latency in dynamic scenes. The basic principles of event cameras rely on pixel-independent operation, where each pixel continuously monitors its own logarithmic intensity and generates an event independently when a brightness change exceeds a predefined threshold. This threshold is typically parameterized by a contrast sensitivity value , such that an event is triggered if , where is the intensity at time and is the intensity at the last event time . After an event, the pixel resets its reference intensity to the current value, ensuring subsequent events capture relative changes rather than absolute levels. Event cameras draw inspiration from biological vision systems, particularly the asynchronous spiking behavior of retinal ganglion cells, which respond selectively to temporal contrast changes in the visual field. This neuromorphic approach, rooted in engineering principles that mimic neural processing, prioritizes efficiency by transmitting sparse data only where and when motion or illumination varies. Key terminology includes address events (AEs), which encode the spatial coordinates of the pixel, a timestamp for the event occurrence, and polarity (ON for positive brightness increase or OFF for decrease). These events form an asynchronous data stream that represents dynamic scene information with microsecond precision.History and Development

The concept of event cameras emerged from neuromorphic engineering, a field initiated by Carver Mead at the California Institute of Technology in the 1980s, where he developed analog very-large-scale integration (VLSI) circuits modeled after biological neural systems to process visual information efficiently.[4] Mead's foundational work laid the groundwork for bio-inspired vision hardware, emphasizing low-power, parallel computation akin to the retina.[5] In the early 1990s, Mead's student Misha Mahowald advanced this by creating the first practical silicon retina, an adaptive and energy-efficient device that replicated early visual processing through logarithmic compression and spatial filtering directly on the chip, achieving dynamic ranges far exceeding traditional sensors.[6] Subsequent refinements in the 1990s and early 2000s at institutions like the Institute of Neuroinformatics (INI) in Zurich focused on asynchronous, change-detection mechanisms, bridging the gap from theoretical models to functional prototypes.[7] A major milestone occurred in 2008 with the invention of the first practical Dynamic Vision Sensor (DVS) by Patrick Lichtsteiner, Christoph Posch, and Tobi Delbrück at INI, University of Zurich and ETH Zurich; this 128×128 pixel sensor achieved a 120 dB dynamic range and 15 μs latency by outputting asynchronous events only for significant brightness changes, enabling high temporal resolution without frame-based overhead. This device marked the transition from research prototypes to viable neuromorphic vision systems.[8] Commercialization accelerated in the 2010s through iniLabs, a spin-off from INI founded by Tobi Delbrück and colleagues in 2010, which produced and sold DVS-based cameras to researchers and early adopters, facilitating broader adoption in robotics and machine vision.[9] By the mid-2010s, iniLabs' efforts evolved into iniVation AG in 2018, expanding production of event-based sensors like the DAVIS series for industrial and academic use.[10] The 2020s brought significant industry advancements, including Sony's IMX636 event-based vision sensor in 2021, co-developed with Prophesee, featuring 1280×720 resolution, 1.06 Geps event rate, and over 86 dB dynamic range in a compact 1/2.5-inch format to enable integration into consumer and automotive devices.[11] Prophesee contributed further with the open-sourcing of its Metavision 3.0 platform in 2022, providing tools for event data processing that supported ongoing ecosystem growth into 2024-2025.[12] Key 2024-2025 milestones included the 5th International Workshop on Event-based Vision at CVPR 2025, which highlighted progress in hardware, algorithms, and datasets, fostering collaboration among over 100 researchers.[13] Influential research from institutions like EPFL (e.g., advances in event-driven SLAM by Davies et al.) and UZH/INI (e.g., Delbrück's sensor innovations) has been synthesized in IEEE surveys, such as Gallego et al.'s comprehensive review of event-based methods, which has over 1,000 citations and underscores the field's shift toward real-time, low-latency vision. Market projections indicate the event camera sector will reach USD 6.19 billion by 2032, driven by demand in autonomous systems and edge AI.[3]Operating Mechanism

Functional Description

The pixel architecture of an event camera consists of an asynchronous delta modulator integrated within each pixel, comprising a logarithmic photoreceptor, a comparator, and an event generator. The logarithmic photoreceptor converts incoming light intensity into a logarithmic voltage signal, enabling a high dynamic range exceeding 120 dB by compressing the photocurrent logarithmically. This photoreceptor continuously tracks the logarithmic brightness , where is the light intensity at pixel coordinates and time . The comparator then monitors the difference between the current logarithmic brightness and the last value that triggered an event, while the event generator handles the asynchronous output when a threshold is crossed.[14] Intensity change detection occurs asynchronously and independently per pixel, with the comparator firing an event when the absolute change in logarithmic brightness exceeds a predefined contrast threshold. Specifically, an event is generated at time if , where is the time of the previous event from that pixel and is the contrast sensitivity threshold, typically set between 0.1 and 0.5 to detect relative changes of 10% to 50%. This mechanism ensures events represent significant temporal contrast rather than absolute intensity, mimicking biological retinal processing. To prevent bursts of events from noise or rapid fluctuations, a refractory period—lasting on the order of microseconds—is enforced after each event, during which the pixel ignores further changes and resets its internal memory.[14] The output from all pixels is serialized using the Address Event Representation (AER) protocol, which employs an asynchronous arbiter to manage a shared digital bus and transmit events without frame synchronization. This protocol prioritizes events from active pixels, achieving readout rates from several MHz to over 1 GHz depending on the sensor design. The resulting data stream is a sparse sequence of discrete events, each encoded as a tuple , where and are the pixel coordinates, indicates the polarity of the brightness change (increase or decrease), and is a timestamp with microsecond resolution, enabling sub-millisecond latency in event reporting.[14]Event Generation and Data Output

Event cameras produce an asynchronous stream of events that is inherently sparse, with output data rates proportional to the dynamics in the scene. In static scenes under constant illumination, the event generation is minimal, often limited to noise-induced activity and resulting in data volumes significantly lower than those of frame-based cameras, which capture the entire sensor array regardless of changes. This sparsity can reduce bandwidth requirements by orders of magnitude in low-motion scenarios, enabling efficient processing for applications requiring real-time responsiveness.[15] The latency of event generation is exceptionally low, with individual pixels responding to intensity changes in the microsecond range—typically around 15 μs—independent of any global frame rate. This per-pixel asynchronous operation allows for sub-millisecond overall system latency, making event cameras suitable for high-speed tasks where traditional cameras suffer from readout delays. Output bandwidth varies dynamically with scene activity, reaching up to several million events per second in fast-moving or high-contrast environments, though it drops substantially in quiescent conditions. However, the stream includes noise events arising from thermal fluctuations in the sensor circuitry and fixed-pattern noise due to transistor mismatch across pixels, which can introduce spurious outputs even in static scenes.[16][15][17] Each event in the output stream is represented as a discrete packet containing the pixel coordinates (x, y), a precise timestamp (t), and a binary polarity (p) indicating whether the intensity change was an increase (ON event, p=+1) or decrease (OFF event, p=-1). This compact format encodes only the occurrence and direction of changes exceeding a threshold, without magnitude information. For visualization and processing, events are often accumulated into derived representations such as time surfaces, which map the most recent timestamp per pixel to create a pseudo-intensity image highlighting recent activity, or voxel grids, which bin events into 3D histograms along spatial and temporal dimensions to preserve asynchronous timing.[15] Bias tuning plays a crucial role in shaping the event stream, as adjustable bias currents in each pixel set the contrast thresholds for triggering ON and OFF events, typically ranging from 10% to 50% relative illumination change. Lower thresholds increase sensitivity to subtle dynamics but amplify noise, while higher thresholds enhance robustness to lighting variations at the cost of missing faint changes; tuning is thus optimized per application to balance event rate, sparsity, and signal quality under specific environmental conditions.[15]Types and Variants

Dynamic Vision Sensors

Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVS) represent the foundational architecture of event cameras, designed to detect and output only changes in light intensity across the visual field, thereby providing asynchronous streams of events rather than fixed-frame images. The original DVS was developed by researchers at the Institute of Neuroinformatics, with the seminal 128×128 pixel implementation introduced in 2008, featuring a temporal contrast sensitivity of approximately 10% and a latency of 15 μs for event generation based on logarithmic changes in pixel illumination.[2] This design draws inspiration from biological retinas, where each pixel independently monitors intensity variations and signals an event only when the logarithmic brightness change exceeds a threshold, typically around 10-15% in early models but improved to 1% or better in subsequent iterations.[18] At the core of a DVS is a two-dimensional array of independent pixels, each equipped with a photodiode and change-detection circuitry that employs an asynchronous delta modulator to track logarithmic light intensity. When a pixel detects a sufficient change, it generates an address event, which is routed to an off-pixel Address Event Representation (AER) readout system that arbitrates and serializes these events for output without buffering or framing.[19] This AER mechanism ensures sparse, timestamped data streams, where each event includes the pixel's (x, y) coordinates, polarity (ON for increase, OFF for decrease), and a precise timestamp, enabling microsecond-level temporal resolution.[19] Unlike frame-based sensors, DVS pixels lack a global frame buffer, allowing purely asynchronous operation that scales with scene dynamics rather than fixed clock rates.[8] Typical DVS implementations feature pixel resolutions ranging from VGA (640×480) to HD (1280×720), balancing spatial detail with readout bandwidth demands.[20] For instance, early pure DVS models like the CeleX-IV from Celex Technologies offer 768×640 resolution with integrated AER for high-speed event output up to 200 million events per second.[21] Similarly, Prophesee's Metavision sensors, such as the GEN 2.3 series, provided 640×480 arrays focused on standalone event detection without hybrid framing.[20] These specifications support applications requiring low-latency motion capture, with power consumption typically in the range of 10-20 mW for the full array under moderate activity, owing to per-pixel event-driven activation that minimizes idle power. Performance hallmarks of DVS include a dynamic range exceeding 120 dB, far surpassing conventional cameras' 60-90 dB, due to the logarithmic encoding that handles extreme lighting variations from 0.1 lux to full sunlight without saturation. Temporal contrast sensitivity, measuring the minimum detectable relative intensity change, achieves values as low as 1% in optimized designs, enabling detection of subtle motions even in low-light conditions.[18] These metrics establish DVS as efficient for sparse, high-fidelity event data, with event rates scaling from kiloevents per second in static scenes to millions under rapid motion.[19]Hybrid and Specialized Variants

Hybrid event cameras integrate asynchronous event-based sensing with traditional frame-based imaging or additional intensity measurements, enabling multimodal data capture that combines the strengths of both approaches for enhanced versatility in dynamic environments.[22] The Dynamic and Active-pixel Vision Sensor (DAVIS) exemplifies this hybrid design by embedding dynamic vision sensor (DVS) pixels alongside active pixel sensor (APS) elements within the same array, allowing simultaneous output of asynchronous events triggered by brightness changes and synchronous grayscale frames at configurable rates.[23] This dual-output capability facilitates applications requiring both high temporal resolution events and conventional intensity images, with commercial models like the DAVIS346 achieving 346 × 260 pixel resolution, over 120 dB dynamic range for events, and frame rates up to 40 fps (as of 2019).[23] An extension, the RGB-DAVIS, incorporates a color filter array (CFA) over the pixels to produce color events and frames, marking an early prototype for chromatic event sensing.[8] The Asynchronous Time-based Image Sensor (ATIS) represents another hybrid variant, augmenting standard DVS event generation with per-pixel absolute intensity encoding through time-to-first-spike measurements, which capture logarithmic light levels via asynchronous exposure periods.[24] This addition provides frame-free absolute luminance data alongside change-detection events, supporting high dynamic range (over 120 dB) and microsecond temporal precision without global shuttering.[25] ATIS pixels operate autonomously, outputting events only for significant changes while periodically signaling intensity, which reduces data volume compared to full-frame sensors and enables efficient processing in resource-constrained systems.[26] Specialized variants optimize event cameras for extreme performance in speed, color fidelity, or integration. High-speed configurations leverage the asynchronous pixel architecture to achieve effective frame rates exceeding 1,000 fps equivalents through sparse event streams, far surpassing traditional cameras in motion-heavy scenarios like vibration analysis or droplet tracking.[27] Color event cameras, such as 2023 prototypes using RGB filters or dichroic separations, extend monochromatic DVS to multichannel event output, enabling wavelength-specific change detection for applications in textured or illuminated scenes.[28] In 2021, advancements like Sony's stacked event-based vision sensors (EVS) (as of 2021) incorporate integrated logic processing in a Cu-Cu bonded pixel-logic chip structure, reducing output latency to microsecond levels by filtering noise events on-chip and minimizing data transmission.[29] These sensors, such as the IMX636 series, maintain 1,280 × 720 resolution with 4.86 μm pixels while achieving up to 92% data reduction through hardware event processing (as of 2021).[29] Other variants include the ESIM sensors, which provide high-resolution event detection for advanced imaging tasks.[30]Related Neuromorphic Technologies

Retinomorphic Sensors

Retinomorphic sensors represent a class of event-driven vision devices that integrate on-chip neural processing to emulate the functional architecture of biological retinas. Unlike conventional frame-based cameras, these sensors detect asynchronous changes in light intensity and perform preliminary signal processing directly at the pixel level, generating sparse spiking outputs that mimic retinal ganglion cell activity. This bio-inspired approach incorporates elements such as center-surround receptive fields, which enhance contrast by comparing illumination in central and surrounding regions of each pixel's field of view.[31] Key features of retinomorphic sensors include hierarchical event processing, where multiple layers of computation filter and refine raw events before output, enabling functions like edge enhancement and motion adaptation at the sensor itself. For instance, center-surround mechanisms suppress uniform illumination changes while amplifying boundaries and dynamic features, reducing noise and computational load downstream. This on-sensor adaptation allows for real-time processing with low power consumption, drawing from neuromorphic engineering principles to achieve efficiencies unattainable in traditional imaging systems.[31] Early prototypes in the 2010s, such as silicon-based implementations of retinomorphic event-based vision sensors, demonstrated these capabilities through asynchronous address-event representation (AER) hardware that outputs spikes only for significant visual changes. More recent advancements, including 2024 integrations of retinomorphic arrays with spiking neural networks, have shown enhanced performance in dynamic scene analysis by embedding temporal memory and adaptive filtering directly into the sensor fabric, such as in perovskite-based designs that support embodied intelligent vision tasks.[31][32][33] In contrast to standard event cameras, which primarily output raw pixel-level events without integrated filtering, retinomorphic sensors incorporate built-in neural-like processing to significantly reduce data volume—often by orders of magnitude—through on-chip suppression of redundant signals, thereby streamlining subsequent computational pipelines.[31]Intensity-Modulated Event Sensors

In event cameras such as dynamic vision sensors (DVS), events in static scenes are generated due to noise processes that are influenced by the absolute intensity of light incident on each pixel, in addition to temporal changes. This arises from adaptive photoreceptors that implement logarithmic compression of the input light intensity, allowing the sensor to convey information about steady-state illumination levels through variations in event frequency. In these designs, the event rate in static scenes increases with intensity at low light levels due to shot noise, enabling asynchronous estimation of ambient light conditions without relying on framed imaging.[34] The core mechanism involves pixel circuits with adaptive feedback loops that adjust the photoreceptor's gain and baseline to handle wide dynamic ranges, typically exceeding 120 dB. These loops stabilize the output voltage to a value corresponding to log(I), while any deviation due to intensity fluctuations or noise triggers events. For static scenes, residual events from thermal or photon noise provide a baseline rate that scales with intensity, facilitating environmental sensing such as illumination estimation. This approach draws bio-inspiration from retinal ganglion cells, where firing rates encode sustained light levels.[34] Notable examples include variants of dynamic vision sensors (DVS) incorporating adaptive elements, such as those tested in parametric benchmarks under varying illumination. The 2025 JRC INVISIONS Neuromorphic Sensors Parametric Tests dataset captures sequences from multiple event cameras across illumination levels from low-light to high-contrast conditions, demonstrating how intensity influences event statistics and noise characteristics for applications like adaptive thresholding. These tests highlight improved performance in intensity-varying environments compared to non-adaptive sensors.[35] A key advantage of this intensity-dependent behavior in event sensors is their ability to perform ambient light estimation directly from event streams, supporting real-time adaptation in low-light scenarios without additional hardware. For instance, by analyzing the noise-induced event rate, systems can dynamically adjust biases to maintain optimal sensitivity, reducing false positives in dim conditions. This is particularly beneficial for robotics in uncontrolled lighting.[34][36] Recent developments from 2024 to 2025 have focused on hardware-efficient implementations using memristors to realize adaptive photoreceptors and rate-modulation circuits. Memristor-based designs enable compact, low-power integration of logarithmic compression and event triggering, with demonstrated energy efficiencies below 1 pJ per event in spiking neuromorphic systems. These advances enhance scalability for edge devices, as shown in hybrid memristor-CMOS prototypes for intensity-sensitive event processing.[37][38]Algorithms and Processing

Image Reconstruction

Image reconstruction in event cameras involves transforming the sparse, asynchronous stream of per-pixel brightness change events into dense visual representations, such as grayscale frames or video sequences, to enable compatibility with conventional computer vision algorithms. This process addresses the inherent sparsity of event data, where only pixels undergoing significant changes are reported, by aggregating events over spatial and temporal dimensions to infer underlying intensity maps. Early methods focused on simple accumulation techniques, while more advanced approaches incorporate temporal weighting and learning-based models to improve fidelity and handle high dynamic range (HDR) conditions. A fundamental technique is event accumulation into time slices, where events within fixed temporal bins are binned to form 2D images, often as binary maps indicating event presence (with polarity for positive/negative changes) or event counts per pixel. This method preserves temporal resolution by creating stacked frames at rates up to several kHz, effectively converting the event stream into a voxel grid for further processing. For instance, binary images per timestamp bin highlight edges and motion contours without intensity values, serving as a basic proxy for visual scenes. To better approximate continuous intensity, weighted accumulation applies decay functions to prioritize recent events, mitigating the effects of historical data accumulation. A common formulation is the time surface or intensity map , where denotes pixel coordinates, are event timestamps at that pixel, is a decay constant (typically 10-100 ms), and the sum is over recent events . This exponential decay models the recency of brightness changes, producing a grayscale-like representation that fades older events, as introduced in seminal work on event-based feature representation. Advanced algorithms leverage these accumulation principles for HDR reconstruction and video synthesis. Fast-HDR methods integrate event data with optional frame inputs from hybrid sensors to recover wide dynamic range images in real-time, using variational optimization or filters to estimate absolute intensities while exploiting the event camera's 120+ dB sensitivity. Deep learning approaches, such as the recurrent convolutional network in E2VID (Events-to-Video), reconstruct high-speed videos from events by predicting frame-to-frame intensity changes, achieving up to 240 fps with low latency on embedded hardware. More recent 2024 methods, like E2HQV, enhance this with model-aided diffusion models for higher-quality outputs, incorporating theoretical priors on event generation to reduce artifacts in sparse regions. These techniques address key challenges inherent to event data, including the absence of motion blur—due to microsecond temporal resolution that captures instantaneous changes—and resolution limits from event sparsity, which can underrepresent static areas but are mitigated through temporal integration and learning-based upsampling. Evaluation typically employs peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) to compare reconstructed frames against ground-truth intensity images, with state-of-the-art methods achieving around 10-12 dB on benchmark datasets like MVSEC, establishing perceptual quality for downstream tasks.[39]Feature Extraction and Convolutions

Feature extraction in event cameras involves processing asynchronous event streams to identify spatial patterns, leveraging the sensors' sparse and temporally precise outputs for efficient computation. Unlike traditional frame-based methods, event-based feature extraction employs local receptive fields applied directly to event surfaces, where events are represented as point clouds in space-time. These fields capture neighborhood interactions around each event, enabling the detection of edges, corners, and textures without full image reconstruction. This approach draws from neuromorphic principles, mimicking retinal processing for low-latency spatial analysis.[40] A key method is time-surface convolutions, which represent the temporal history of events in a local neighborhood as a continuous surface. For an event at position (x, y) and time t, the time surface τ(x, y, t) is defined as τ(x, y, t) = t - t_last(x, y), where t_last(x, y) is the timestamp of the most recent event at that pixel. Convolutions with kernels, such as Gaussian or oriented filters, are then applied to this surface to extract features like gradients or orientations, preserving the asynchronous nature of the data. This technique, introduced in hierarchical event-based processing frameworks, allows for robust pattern recognition by propagating features across layers. Algorithms for feature extraction often integrate spiking convolutions within spiking neural networks (SNNs), where events trigger sparse activations that propagate through convolutional layers. These networks process events as spikes, using surrogate gradients for training to approximate backpropagation while maintaining biological plausibility and energy efficiency. Seminal work demonstrated their use in gesture recognition with low-power consumption, achieving high accuracy on event data. Recent advancements from 2023 to 2025 have focused on event-based convolutional neural networks (CNNs) tailored for tasks like edge detection, incorporating sparsity-aware operations to handle the irregular event distribution. For instance, hybrid architectures combine time-surface representations with CNN backbones to detect edges in high-speed scenarios, outperforming traditional methods in dynamic range. These developments emphasize adaptive kernels that update only on active events, enhancing real-time performance. The efficiency of these methods stems from the inherent sparsity of event data, which reduces the number of parameters and computations compared to dense frame-based convolutions—often by orders of magnitude, as only changed pixels are processed. Implementations on GPUs leverage batched event representations for parallel kernel applications, while neuromorphic chips like SENECA enable on-chip spiking convolutions with sub-milliwatt power draw, suitable for edge devices. Representative examples include orientation-selective filters applied to time surfaces for texture analysis, where multi-scale Gabor-like kernels identify directional patterns in event streams, facilitating applications in material inspection without motion artifacts. These filters, learned hierarchically, achieve selectivity to specific angles, improving discrimination of fine textures in varying lighting. In hybrid approaches, features extracted from event convolutions can complement reconstructed images for enhanced spatial detail, though direct event processing remains preferred for speed.[40]Motion Detection and Object Tracking

Event cameras excel in motion detection by leveraging the temporal patterns of asynchronous events, which encode pixel-level brightness changes over time, enabling precise estimation of motion vectors without relying on full frame reconstruction. A foundational technique for motion detection involves local plane fitting, where events are modeled as lying on a plane in space-time coordinates. This approach assumes that events generated by a moving edge align approximately on a plane defined by the equation , where are the spatial and temporal coordinates of event , and parameters and correspond to the inverse components of the motion velocity. Optimization minimizes the residuals, such as , to estimate local velocity, providing a computationally efficient way to compute normal flow or edge motion.[41] Contrast maximization enhances this plane-fitting method by warping events along hypothesized motion trajectories to maximize the sharpness of the resulting event image, effectively aligning events from the same edge. Introduced as a unifying framework for event-based vision tasks, this technique iteratively optimizes motion parameters to minimize variance in warped event timestamps, yielding robust estimates even under high-speed motion or noise. For instance, in ego-motion scenarios, contrast maximization has demonstrated sub-pixel accuracy in aligning event streams from dynamic scenes.[42][43] Optical flow estimation in event cameras builds on event alignment principles, treating the sparse event stream as a continuous motion field. Methods align events by solving for dense flow fields that map event positions across time, often extending contrast maximization to produce sharp images of warped events (IWEs) despite large displacements or complex scenes. This alignment-based optical flow achieves high temporal resolution, capturing motions at microsecond scales, and outperforms traditional frame-based methods in low-light or high-dynamic-range conditions.[44][45] Advanced object tracking algorithms integrate filtering techniques with event clustering to handle multiple dynamic objects. Event clusters, formed by grouping spatially and temporally proximate events, serve as compact representations of moving objects, upon which Kalman filters predict and update trajectories by fusing cluster centroids with motion models. Particle filters extend this for non-linear scenarios, sampling possible object states from event clusters to robustly track under occlusions or erratic motion, achieving real-time performance on resource-constrained hardware. Since 2024, spiking neural network (SNN)-based trackers have emerged as efficient alternatives, processing event streams directly through bio-inspired spiking neurons to estimate object positions with low power consumption, suitable for edge deployment.[46][47] Performance metrics for these methods emphasize precision and speed: tracking errors are typically reported in pixels, with state-of-the-art approaches achieving 1-2 pixel accuracy on benchmark datasets, while end-to-end latencies remain below 1 ms due to the asynchronous nature of event processing. By 2025, integrations with simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) systems have advanced ego-motion estimation, combining event-based optical flow with geometric solvers for full six-degree-of-freedom pose recovery, enabling robust tracking in unstructured environments like autonomous navigation.[17][48]Applications

Robotics and Autonomous Navigation

Event cameras have enabled significant advancements in robotics by providing asynchronous, high-temporal-resolution sensing that supports real-time perception for autonomous navigation in challenging environments. In high-speed obstacle avoidance, these sensors detect brightness changes with microsecond latency, allowing robots to distinguish static from dynamic obstacles using temporal event patterns and react swiftly without the delays inherent in frame-based cameras. For instance, a quadrotor system equipped with an event camera achieved reliable avoidance of fast-moving obstacles at relative speeds up to 10 m/s, with an end-to-end latency of 3.5 milliseconds, demonstrating onboard computation feasibility for agile flight.[49] Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) in dynamic environments benefits from event-based Visual Odometry (VO) algorithms like EVO, which perform 6-DOF parallel tracking and mapping in real-time by leveraging geometric constraints on event streams to estimate camera poses at hundreds per second. EVO excels in GPS-denied settings, such as planetary terrains, where traditional cameras suffer from motion blur and low dynamic range, enabling robust trajectory estimation during rapid maneuvers. Recent extensions, including event-based SLAM frameworks, further enhance accuracy by up to 130% in high-dynamic-range or high-speed scenarios compared to event-only baselines.[50][51] Practical deployments highlight these capabilities in aerial and legged robotics. For quadruped robots, event cameras facilitate terrain adaptation by providing sparse, motion-compensated event data to adjust locomotion controllers in real-time; one implementation enabled agile object catching at speeds up to 15 m/s from 4 meters away, with an 83% success rate, by fusing events with inertial measurements for precise pose estimation.[52] Key benefits include low power consumption, suitable for edge devices in resource-constrained robots, as event cameras only transmit data on intensity changes, reducing bandwidth and energy needs compared to continuous frame capture. Additionally, their asynchronous output inherently avoids motion blur, ensuring reliable perception during high-acceleration movements. Case studies from the University of Zurich (UZH) and collaborations with EPFL, such as the Robotics and Perception Group projects, demonstrate these advantages through Visual-Inertial Odometry (VIO) integrations. For example, continuous-time VIO fuses event streams with IMU data at 1 kHz, improving pose accuracy by up to fourfold in dynamic scenes and enabling scale estimation with position errors below 1% of scene depth. These systems reference event-based motion detection for feature tracking but prioritize sensor fusion for closed-loop control.[53][54]Computer Vision and Machine Learning

Event cameras have revolutionized computer vision and machine learning by providing asynchronous, high-temporal-resolution data that enables efficient processing of dynamic scenes, particularly in low-light or high-speed conditions. Unlike traditional frame-based cameras, event data consists of sparse, pixel-wise brightness changes, which must be adapted for integration into standard CV/ML pipelines. Key datasets facilitate this adaptation, including N-MNIST, a neuromorphic version of the MNIST dataset where static images are converted to event streams via simulated saccades on a dynamic vision sensor (DVS), enabling benchmarking of digit recognition tasks with spiking neural networks (SNNs). Similarly, the DVS Gesture dataset captures 11 hand gesture classes from 29 subjects under varying lighting, providing over 2,900 samples for action recognition and achieving baseline accuracies above 90% with convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Recent benchmarks from the 2025 CVPR Event Vision Workshop, including challenges on the 3ET dataset for eye-tracking and MouseSIS for instance segmentation, highlight ongoing advancements.[55][56][13] To leverage event data in ML models, common techniques involve event-to-frame conversion, where asynchronous events are aggregated into image-like representations such as time surfaces or voxel grids to feed into CNNs, allowing the application of established architectures like ResNet for classification. For instance, events within fixed time windows are binned into 2D or 3D histograms, preserving temporal information while enabling end-to-end training with backpropagation. More bio-inspired approaches use SNNs, trained directly on event streams via surrogate gradient methods, which approximate the non-differentiable Heaviside spike function with smooth surrogates (e.g., sigmoid or fast sigmoid) to enable gradient descent optimization. This surrogate gradient learning has been applied to event-based inputs, achieving over 99% accuracy on simplified classification tasks like four-class pattern recognition from DVS recordings. These methods bridge the gap between event sparsity and dense neural computations, reducing latency compared to frame-based processing.[57][58] In specific CV tasks, event cameras excel in gesture recognition, where models like CNNs on DVS Gesture data attain 96.5% accuracy across 11 classes, outperforming frame-based methods in speed and power efficiency due to the sensor's microsecond latency. For anomaly detection in videos, event streams enable sparse, real-time identification of unusual patterns, such as in surveillance, by exploiting the sensor's sensitivity to motion changes while ignoring static backgrounds. Advancements in 2024 introduced hybrid models fusing event data with RGB frames, enhancing robustness in challenging environments; for example, combining a 20-fps RGB camera with events matches the latency of high-frame-rate sensors while reducing bandwidth by orders of magnitude, improving mean average precision (mAP) by up to 3.4 in scenarios with partially observable objects, including low-light dynamic scenes, over RGB alone. These integrations, often via feature sharing in multimodal networks, underscore event cameras' role in scalable, energy-efficient ML for vision tasks.[56][17]Emerging and Specialized Uses

In biomedicine, event cameras have enabled precise tracking of microparticles undergoing Brownian motion, offering advantages in speed and sensitivity over traditional frame-based imaging. A 2025 study demonstrated that neuromorphic cameras, through optical modulation techniques, significantly enhance the detection and centroid estimation of inert microparticles by generating sparse, high-frequency event streams that capture subtle motion changes without invasive interventions.[59] This approach has been applied to both passive Brownian particles and active matter, achieving sub-millisecond temporal resolution for analyzing thermal fluctuations in microfluidic environments.[60] Additionally, event-based sensors are being integrated into retinal prosthesis interfaces to simulate natural visual processing, mimicking the asynchronous activity of retinal ganglion cells for more efficient phosphene generation in prosthetic vision systems.[61] These systems process dynamic scenes with low power, reducing latency in visual feedback for users with retinal degeneration.[62] In the automotive sector, event cameras from Prophesee, such as the 2024-released GenX320 sensor, support advanced driver assistance by providing high-dynamic-range imaging that maintains performance in challenging lighting conditions, including rapid transitions from dark to bright environments.[63] These sensors enable low-latency object detection and tracking, as evidenced by a large-scale 2024 dataset comprising over 39 hours of diverse driving scenarios, which facilitates robust perception for autonomous vehicles.[64] Their asynchronous event generation helps mitigate issues like sensor saturation from intense light sources, contributing to safer navigation in high-contrast scenes.[17] Beyond these domains, event cameras are applied in astronomy to capture fast transient events, leveraging their microsecond-level temporal resolution and wide dynamic range to observe rapid celestial phenomena that conventional telescopes might miss.[65] In virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), they facilitate ultra-low-latency hand and eye tracking, enabling seamless interaction in head-mounted displays; for instance, hybrid event-frame systems achieve gaze estimation updates exceeding 10,000 Hz with accuracy comparable to high-end commercial trackers.[66] Collaborations like Prophesee and Ultraleap have integrated event-based hand tracking into AR devices, reducing motion-to-photon latency for immersive experiences.[67] In human-centered applications, particularly emotion detection through neuromorphic face analysis, event cameras capture subtle facial dynamics for real-time affective computing. The NEFER dataset, featuring paired RGB-event videos of emotional expressions, supports models that recognize seven basic emotions with improved efficiency over frame-based methods, achieving high accuracy in sparse data regimes.[68] Surveys highlight neuromorphic approaches for facial landmark detection and expression analysis, enabling low-power, privacy-preserving interfaces in wearables and social robotics.[69] These advancements underscore event cameras' role in bridging biological inspiration with practical, latency-sensitive human interaction systems.Advantages, Challenges, and Future Outlook

Key Advantages

Event cameras provide exceptionally low latency in capturing visual changes, with temporal resolutions on the order of 1 microsecond, enabling near-instantaneous response to dynamic scenes without the delays inherent in frame-based sampling of traditional CMOS sensors. This is complemented by their high dynamic range, typically exceeding 120–140 dB, far surpassing the 60 dB capability of conventional CMOS cameras, which allows them to operate effectively across extreme lighting conditions from direct sunlight to near-darkness without saturation or loss of detail.[71][72] Their asynchronous, event-driven output results in significant data efficiency, particularly in sparse-motion environments where only changes in pixel intensity are recorded, leading to bandwidth reductions of up to 100 times compared to the continuous full-frame data streams of traditional cameras. This sparsity minimizes redundant information transmission, making event cameras suitable for resource-constrained systems while preserving essential temporal and spatial details.[73][1] Power consumption is another key benefit, with event camera sensors operating at levels below 100 mW—often around 10–16 mW at the die level—contrasted against the watt-scale requirements of frame-based cameras that continuously process and transmit pixel data. This efficiency stems from the selective activation of pixels only when intensity thresholds are crossed, drastically reducing energy use in static or low-activity scenes.[74][1][20] In terms of robustness, event cameras eliminate motion blur entirely by timestamping individual pixel events rather than integrating exposures over fixed intervals, effectively supporting high-speed capture equivalent to over 10,000 frames per second for fast-moving objects. This enables precise tracking of rapid dynamics that would otherwise degrade in conventional imaging. Additionally, their bio-inspired design, drawing from the asynchronous signaling of biological retinas, mimics human visual processing by focusing on salient changes, facilitating more natural and efficient downstream analysis.[71][75][76]Limitations and Technical Challenges

Event cameras, while excelling in dynamic range and temporal resolution, do not capture absolute intensity values, instead recording only relative changes in logarithmic brightness, which necessitates calibration to reconstruct meaningful photometric information and can introduce errors in static or uniform scenes.[77] This limitation stems from the asynchronous nature of event generation, where pixels trigger based on contrast thresholds without providing baseline luminance, requiring additional techniques like neural reconstruction for applications demanding absolute measurements.[78] In low-light conditions, event cameras suffer from increased noise due to photon shot noise and thermal leakage currents, which generate spurious background activity events that degrade signal quality and complicate downstream processing.[79] This noise is particularly pronounced below 1 lux, where the sparse event stream becomes overwhelmed by random triggers, reducing the sensor's effectiveness despite its high dynamic range advantage over frame-based cameras.[80] Current commercial event cameras are limited to resolutions up to approximately 1 megapixel (e.g., HD 1280x720 formats like Sony's IMX636), constrained by pixel circuitry complexity and fabrication challenges that hinder scaling without compromising event rate or sensitivity.[81] Higher-resolution prototypes, such as those exceeding 1MP, are under development to address this, but they remain experimental due to increased power and bandwidth requirements.[82] A key challenge is the lack of standardization in event data formats, with no unified representation for asynchronous streams (x, y, polarity, timestamp), leading to fragmented interoperability across hardware and software ecosystems.[83] Efforts like JPEG XE aim to establish common codecs, but as of 2025, proprietary formats persist, complicating integration in multi-vendor systems.[83] Processing dense scenes with high event rates poses significant computational demands, as the asynchronous, high-throughput data (up to millions of events per second) requires efficient algorithms to avoid bottlenecks on resource-constrained devices like mobile platforms. This sparsity benefit turns into a liability in cluttered environments, where event volumes explode, necessitating specialized hardware accelerators or approximations to maintain real-time performance.[84] Recent research in 2024-2025 has focused on machine learning-based noise suppression, with methods like EDmamba using spatiotemporal state space models to decouple spatial artifacts and temporal inconsistencies, achieving up to 2.1% accuracy gains on benchmarks while processing 100K events in 68ms.[85] Similarly, unsupervised 3D spatiotemporal filters have demonstrated effective background activity reduction in low-light scenarios through adaptive learning.[86] Scalability to consumer devices remains hindered by high costs—often exceeding $300 per module due to specialized neuromorphic architectures—and integration barriers, including the need for custom drivers and power management in standard smartphone or IoT ecosystems.[87] Limited production volumes further elevate prices, delaying widespread adoption beyond industrial and research applications.[87]Recent Developments and Market Trends

In 2024, significant hardware advancements in event cameras included the widespread adoption of the Sony IMX636 sensor, developed in collaboration with Prophesee, which achieves a peak output of 1 billion events per second and supports 1280x720 resolution with over 120 dB dynamic range.[88] This sensor powers compact evaluation kits like Prophesee's EVK4 HD, enabling high-throughput applications in dynamic environments.[89] Prophesee also expanded its ecosystem through partnerships, including with LUCID Vision Labs for the Triton2 EVS camera series and AMD for the Kria KV260 Starter Kit integrating IMX636-based sensors, facilitating easier integration into embedded systems.[90] These developments build on Prophesee's 2022 acquisition of iniVation (formerly iniLabs), enhancing neuromorphic sensor portfolios for industrial and research use.[91] Software tools have matured alongside hardware, with Prophesee's Metavision SDK 5 PRO emerging as a leading open-source platform, offering over 64 algorithms, 105 code samples, and support for event-based processing in C++ and Python.[92] The SDK enables developers to handle high-speed event streams and has been updated to support new sensors like the IMX636. In 2025, the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) released the INVISIONS Neuromorphic Sensors Parametric Tests dataset, comprising 2,156 scenes captured with commercial event cameras under controlled conditions to benchmark performance in computer vision tasks such as motion estimation and vibration analysis.[93] This resource addresses gaps in standardized evaluation, providing ground-truth data for bias tuning, illumination robustness, and artifact reduction.[35] Market growth for event cameras is projected at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 25.2% from USD 0.86 billion in 2024 to USD 5.2 billion by 2032, driven by demand in autonomous systems and surveillance.[94] In automotive applications, event cameras enable low-latency vision, with a 2024 study demonstrating that combining them with 20 fps RGB cameras achieves sub-millisecond response times comparable to 5,000 fps systems while reducing bandwidth by orders of magnitude.[17] Adoption is accelerating in consumer electronics, evidenced by Prophesee's €15 million investment in neuromorphic AI for mobile devices and partnerships like with Ultraleap for XR gesture control and Zinn Labs for smart eyewear gaze tracking.[90] Emerging trends include hybrid neuromorphic chips that integrate event sensors with spiking neural networks for energy-efficient processing, as explored in 2025 research on edge AI architectures for real-time object detection.[95] Efforts toward data format standardization are gaining traction in academia and industry, with proposals for efficient event encoding to facilitate interoperability across datasets and hardware.[96] These advancements position event cameras for broader commercialization by 2030, particularly in resource-constrained environments.References

- https://arxiv.org/html/2502.18490v1