Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Extensor hallucis longus muscle

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

| Extensor hallucis longus muscle | |

|---|---|

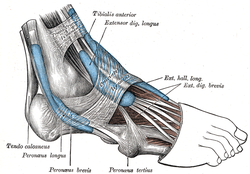

The mucous sheaths of the tendons around the ankle. Lateral aspect. (Ext. hall. long. labeled at upper left.) | |

Animation | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Arises from the middle portion of the fibula on the anterior surface and the interosseous membrane |

| Insertion | Inserts on the dorsal side of the base of the distal phalanx of the big toe |

| Artery | Anterior tibial artery |

| Nerve | Deep fibular nerve, L5 (L4-S1) |

| Actions | Extends (raises) the big toe and assists in dorsiflexion of the foot at the ankle. Also is a weak evertor/invertor |

| Antagonist | Flexor hallucis longus, flexor hallucis brevis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus extensor hallucis longus |

| TA98 | A04.7.02.040 |

| TA2 | 2650 |

| FMA | 22533 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The extensor hallucis longus muscle is a thin skeletal muscle, situated between the tibialis anterior and the extensor digitorum longus. It extends the big toe and causes dorsiflexion of the foot. It also assists with foot eversion and inversion.

Structure

[edit]The muscle ends as a tendon of insertion. The tendon passes through a distinct compartment in the inferior extensor retinaculum of foot. It crosses anterior tibial vessels lateromedially near the bend of the ankle.[citation needed] In the foot, its tendon is situated at along the medial side of the dorsum of the foot.[1] Opposite the metatarsophalangeal articulation, the tendon gives off a thin prolongation on either side, to cover the surface of the joint. An expansion from the medial side of the tendon is usually inserted into the base of the proximal phalanx.[citation needed]

Origin

[edit]The extensor hallucis longus muscle arises from the middle portion of[2] the anterior surface[citation needed] of the fibula and adjacent interosseous membrane of the leg.[3] Its origin is medial to the origin of the extensor digitorum longus muscle.[citation needed]

Insertion

[edit]The muscle inserts at the base of the distal phalanx of the great toe.[4]

Nerve supply

[edit]The muscle receives motor innervation from the deep fibular nerve (L5)[3] (a branch of common fibular nerve).

Relations

[edit]The anterior tibial vessels and deep fibular nerve pass between this muscle and the tibialis anterior muscle.

Variation

[edit]Occasionally united at its origin with the extensor digitorum longus.

The extensor ossis metatarsi hallucis, a small muscle, sometimes found as a slip from the extensor hallucis longus, or from the tibialis anterior, or from the extensor digitorum longus, or as a distinct muscle; it traverses the same compartment of the transverse ligament with the extensor hallucis longus.

Actions/movements

[edit]The muscle extends the big toe (primary action), and causes dorsiflexion of the foot (secondary action).[3]

Additional images

[edit]-

Cross-section through middle of leg. (Extensores longi digitorum et hallucis labeled at upper left.)

-

Dorsum of Foot. Deep dissection.

-

Dorsum of Foot. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Medial view

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Lateral view.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 481 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 481 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ a b c Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:15:st-0402 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Leg: Muscles"

- University of Washington