Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Toes | |

|---|---|

Toes on the human left foot. The innermost toe (left in image), which is normally called the big toe, is the hallux. | |

Bones of the foot (the toe bones are the ones in green, blue and orange) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | digiti pedis |

| MeSH | D014034 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.046 |

| TA2 | 170 |

| FMA | 25046 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Toes are the digits of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being digitigrade. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being plantigrade; unguligrade animals are those that walk on hooves at the tips of their toes.

Structure

[edit]

There are normally five toes present on each human foot. Each toe consists of three phalanx bones, the proximal, middle, and distal, with the exception of the big toe (Latin: hallux). For a minority of people, the little toe also is missing a middle bone. The hallux only contains two phalanx bones, the proximal and distal. The joints between each phalanx are the interphalangeal joints. The proximal phalanx bone of each toe articulates with the metatarsal bone of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal joint. Each toe is surrounded by skin, and present on all five toes is a toenail.

The toes are, from medial to lateral:

- the first toe, also known as the hallux ("big toe", "great toe", "thumb toe"), the innermost toe;

- the second toe, ("index toe", "pointer toe");

- the third toe, ("middle toe");

- the fourth toe, ("fore toe", "ring toe");

- the fifth toe, ("baby toe", "little toe", "pinky toe", "small toe"), the outermost toe.

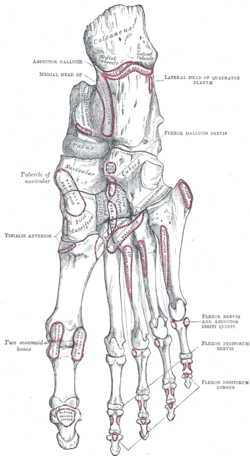

Muscles

[edit]Toe movement is generally flexion and extension (movement toward the sole or the back of the foot, resp.) via muscular tendons that attach to the toes on the anterior and superior surfaces of the phalanx bones.[1]: 573

With the exception of the hallux, toe movement is generally governed by action of the flexor digitorum brevis and extensor digitorum brevis muscles. These attach to the sides of the bones,[1]: 572–75 making it impossible to move individual toes independently. Muscles between the toes on their top and bottom also help to abduct and adduct the toes.[1]: 579 The hallux and little toe have unique muscles:

- The hallux is primarily flexed by the flexor hallucis longus muscle, located in the deep posterior of the lower leg, via the flexor hallucis longus tendon. Additional flexion control is provided by the flexor hallucis brevis. It is extended by the abductor hallucis muscle and the adductor hallucis muscle.

- The little toe has a separate set of control muscles and tendon attachments, the flexor and abductor digiti minimi. Numerous other foot muscles contribute to fine motor control of the foot. The connective tendons between the minor toes account for the inability to actuate individual toes.

Blood supply

[edit]The toes receive blood from the digital branches of the plantar metatarsal arteries and drain blood into the dorsal venous arch of the foot.[1]: 580–81

Nerve supply

[edit]Sensation to the skin of the toes is provided by five nerves. The superficial fibular nerve supplies sensation to the top of the toes, except between the hallux and second toe, which is supplied by the deep fibular nerve, and the outer surface of the fifth toe, supplied by the sural nerve. Sensation to the bottom of the toes is supplied by the medial plantar nerve, which supplies sensation to the great toe and inner three-and-a-half toes, and the lateral plantar nerve, which supplies sensation to the little toe and half of the sensation of the fourth toe.

In humans, the hallux is usually longer than the second toe, but in some individuals, it may not be the longest toe. There is an inherited trait in humans, where the dominant gene causes a longer second toe ("Morton's toe" or "Greek foot") while the homozygous recessive genotype presents with the more common trait: a longer hallux.[2] People with the rare genetic disease fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva characteristically have a short hallux which appears to turn inward, or medially, in relation to the foot.

Variation

[edit]Humans usually have five toes on each foot. When more than five toes are present, this is known as polydactyly. Other variants may include syndactyly or arachnodactyly. Forefoot shape, including toe shape, exhibits significant variation among people; these differences can be measured and have been statistically correlated with ethnicity.[3] Such deviations may affect comfort and fit for various shoe types. Research conducted for the U.S. Army indicated that larger feet may still have smaller arches, toe length, and toe-breadth.[4]

Function

[edit]The human foot consists of multiple bones and soft tissues which support the weight of the upright human. Specifically, the toes assist the human while walking,[5] providing balance, weight-bearing, and thrust during gait.

Clinical significance

[edit]A sprain or strain to the small interphalangeal joints of the toe is commonly called a stubbed toe. A sprain or strain where the toe joins to the foot is called turf toe.

Long-term use of improperly sized shoes can cause misalignment of toes, as well as other orthopedic problems.

Morton's neuroma commonly results in pain and numbness between the third and fourth toes of the sufferer, due to it affecting the nerve between the third and fourth metatarsal bones.[6]

The big toe is also the most common locus of ingrown nails, and its proximal phalanx joint is the most common locus for gout attacks.

Deformity

[edit]Deformities of the foot include hammer toe, trigger toe, and claw toe. Hammer toe can be described as an abnormal contraction or “buckling” of a toe. This is done by a partial or complete dislocation of one of the joints, which form the toes. Since the toes are deformed further, these may press against a shoe and cause pain. Deformities of the foot can also be caused by rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus. Deformities may predispose to ulcers and pain, especially when shoe-wearing.

A common problem involving the big toe is the formation of bunions. These are structural deformities of the bones and the joint between the foot and big toe, and may be painful.[7] Similar deformity involving the fifth toe is described as tailor's bunion or bunionette.

In polydactyly (which can also affect the fingers) one or more extra toes are present.

In reconstruction

[edit]A favourable option for the reconstruction of missing adjacent fingers[8]/multiple digit amputations, i.e. such as a metacarpal hand reconstruction, is to have a combined second and third toe transplantation.[9] Third and fourth toe transplantation to the hand in replacing lost fingers is also a viable option.[10]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Tā

[edit]The Old English term for toe is tā (plural tān). This is a contraction of tāhe, and derives from Proto-Germanic *taihwǭ (cognates: Old Norse tá, Old Frisian tāne, Middle Dutch tee, Dutch teen (perhaps originally a plural), Old High German zēha, German Zehe), perhaps originally meaning 'fingers' as well (many Indo-European languages use one word to mean both 'fingers' and 'toes', e.g. digit), and thus from PIE root *deyḱ- — 'to show'.[11]

Hallux

[edit]

In classical Latin, hallex,[12][13] allex,[12][14] hallus[12] and allus,[12] with genitive (h)allicis and (h)alli, are used to refer to the big toe. The form hallux (genitive, hallucis) currently in use is however a blend word of the aforementioned forms.[12][15] Compare pollex, the equivalent term for the thumb.

Evolution

[edit]Haeckel traces the standard vertebrate five-toed schema from fish fins via amphibian ancestors.[16]

Other animals

[edit]

In birds with anisodactyl or heterodactyl feet, the hallux is opposed or directed backwards and allows for grasping and perching.

While the thumb is often mentioned[by whom?] as one of the signature characteristics in humans, this manual digit remains partially primitive and is actually present in all primates. In humans, the most derived digital feature is the hallux.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Toes – relative lengths of first and second - 189200

- ^ Hawes, MR; Sovak, D; Miyashita, M; Kang, SJ; Yoshihuku, Y; Tanaka, S (Jan 1994). "Ethnic differences in forefoot shape and the determination of shoe comfort". Ergonomics. 37 (1): 187–96. doi:10.1080/00140139408963637. PMID 8112275.

- ^ Freedman, A., Huntington, E.C., Davis, G.C., Magee, R.B., Milstead, V.M. and Kirkpatrick, C.M.. 1946. Foot Dimensions of Soldiers (Third Partial Report), Armored Medical Research Laboratory, Fort Knox, Kentucky.

- ^ Janey Hughes, Peter Clark, & Leslie Klenerman. The Importance of the Toes in Walking. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Vol. 72-B, No. 2. March, 1990. [1] Archived 2008-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Morton's Neuroma". Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. "Bunions". Archived from the original on 2011-12-08. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ Wei, Fu-Chan; Colony, Lee H.; Chen, Hung-Chi; Chuang, Chwei-Chin; Noordhoff, Samuel M. (1989). "Combined Second and Third Toe Transfer". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 84 (4): 651–61. doi:10.1097/00006534-198984040-00016. PMID 2780906.

- ^ Cheng, Ming-Huei; Wei, Fu-Chan; Santamaria, Eric; Cheng, Shao-Lung; Lin, Chih-Hung; Chen, Samuel H. T. (1998). "Single versus Double Arterial Anastomoses in Combined Second- and Third-Toe Transplantation". Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 102 (7): 2408–12, discussion 2413. doi:10.1097/00006534-199812000-00021. PMID 9858177. S2CID 12036342.

- ^ Lutz, Barbara S.; Wei, Fu-Chan (2002). "Basic Principles on Toe-to-Hand Transplantation" (PDF). Gung Medical Journal. 25 (9): 568–76. PMID 12479617. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Toe.

- ^ a b c d e Hyrtl, J. (1880). Onomatologia Anatomica. Geschichte und Kritik der anatomischen Sprache der Gegenwart. Wien: Wilhelm Braumüller. K.K. Hof- und Universitätsbuchhändler. p. 248–249. online at Biodiversity Library.

- ^ Triepel, H. (1908). Memorial on the anatomical nomenclature of the anatomical society. In A. Rose (Ed.), Medical Greek. Collection of papers on medical onomatology and a grammatical guide to learn modern Greek (pp. 176–93). New York: Peri Hellados publication office.

- ^ Lewis, C.T. & Short, C. (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Triepel, H. (1910). Die anatomischen Namen. Ihre Ableitung und Aussprache. Mit einem Anhang: Biographische Notizen.(Dritte Auflage). Wiesbaden: Verlag J.F. Bergmann.

- ^

Haeckel, Ernst Heinrich Philipp August (1874). The Evolution of Man. Library of Alexandria. Vol. 1. Library of Alexandria (published 1923). ISBN 9781465548931. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

The thorough investigations of Gegenbaur have shown that the fish's fins [...] are many-toed feet. The various cartilaginous or bony radii that are found in large numbers in each fin correspond to the fingers of toes of the higher Vertebrates. The several joints of each fin-radius correspond to the various parts of the toe. Even in the Dipneusta the fin is of the same construction as in the fishes; it was afterwards gradually evolved into the five-toed form, which we first encounter in the Amphibia. The reduction of the number of toes to six, and then to five, probably took place in the second half of the Devonian period - at the latest, in the subsequent Carboniferous period - in those Dipneusta which we regard as the ancestors of the Amphibia. [...] The fact that the toes number five is of great importance, because they have clearly been transmitted from the Amphibia to all the higher Vertebrates. Man entirely resembles his amphibian ancestors in this respect, and indeed in the whole structure of the bony skeleton of his five-toed extremities. A careful comparison of the skeleton of the frog with our own is enough to show this. [...] There is absolutely no reason why there should be five toes in the fore and hind feet in the lowest Amphibia, the reptiles, and the higher Vertebrates, unless we ascribe it to inheritance from a common stem-form. Heredity alone can explain it. It is true that we find less than five toes in many of the Amphibia and of the higher Vertebrates. But in all these cases we can prove that some of the toes atrophied, and were in time lost altogether.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Lovejoy, C. Owen; Suwa, Gen; Simpson, Scott W.; Matternes, Jay H.; White, Tim D. (October 2009). "The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus Reveals the Postcrania of Our Last Common Ancestors with African Apes". Science. 326 (5949): 100–6. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..100L. doi:10.1126/science.1175833. PMID 19810199. S2CID 19629241.