Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Binary decision diagram

View on Wikipedia

In computer science, a binary decision diagram (BDD) or branching program is a data structure that is used to represent a Boolean function. On a more abstract level, BDDs can be considered as a compressed representation of sets or relations. Unlike other compressed representations, operations are performed directly on the compressed representation, i.e. without decompression.

Similar data structures include negation normal form (NNF), Zhegalkin polynomials, and propositional directed acyclic graphs (PDAG).

Definition

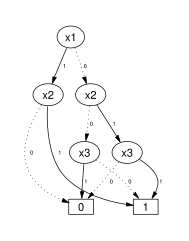

[edit]A Boolean function can be represented as a rooted, directed, acyclic graph, which consists of several (decision) nodes and two terminal nodes. The two terminal nodes are labeled 0 (FALSE) and 1 (TRUE). Each (decision) node is labeled by a Boolean variable and has two child nodes called low child and high child. The edge from node to a low (or high) child represents an assignment of the value FALSE (or TRUE, respectively) to variable . Such a BDD is called 'ordered' if different variables appear in the same order on all paths from the root. A BDD is said to be 'reduced' if the following two rules have been applied to its graph:

- Merge any isomorphic subgraphs.

- Eliminate any node whose two children are isomorphic.

In popular usage, the term BDD almost always refers to Reduced Ordered Binary Decision Diagram (ROBDD in the literature, used when the ordering and reduction aspects need to be emphasized). The advantage of an ROBDD is that it is canonical (unique up to isomorphism) for a particular function and variable order.[1] This property makes it useful in functional equivalence checking and other operations like functional technology mapping.

A path from the root node to the 1-terminal represents a (possibly partial) variable assignment for which the represented Boolean function is true. As the path descends to a low (or high) child from a node, then that node's variable is assigned to 0 (respectively 1).

Example

[edit]The left figure below shows a binary decision tree (the reduction rules are not applied), and a truth table, each representing the function . In the tree on the left, the value of the function can be determined for a given variable assignment by following a path down the graph to a terminal. In the figures below, dotted lines represent edges to a low child, while solid lines represent edges to a high child. Therefore, to find , begin at x1, traverse down the dotted line to x2 (since x1 has an assignment to 0), then down two solid lines (since x2 and x3 each have an assignment to one). This leads to the terminal 1, which is the value of .

The binary decision tree of the left figure can be transformed into a binary decision diagram by maximally reducing it according to the two reduction rules. The resulting BDD is shown in the right figure.

|

|

Another notation for writing this Boolean function is .

Complemented edges

[edit]

An ROBDD can be represented even more compactly, using complemented edges, also known as complement links.[2][3] The resulting BDD is sometimes known as a typed BDD[4] or signed BDD. Complemented edges are formed by annotating low edges as complemented or not. If an edge is complemented, then it refers to the negation of the Boolean function that corresponds to the node that the edge points to (the Boolean function represented by the BDD with root that node). High edges are not complemented, in order to ensure that the resulting BDD representation is a canonical form. In this representation, BDDs have a single leaf node, for reasons explained below.

Two advantages of using complemented edges when representing BDDs are:

- computing the negation of a BDD takes constant time

- space usage (i.e., required memory) is reduced (by a factor at most 2)

However, Knuth[5] argues otherwise:

- Although such links are used by all the major BDD packages, they are hard to recommend because the computer programs become much more complicated. The memory saving is usually negligible, and never better than a factor of 2; furthermore, the author's experiments show little gain in running time.

A reference to a BDD in this representation is a (possibly complemented) "edge" that points to the root of the BDD. This is in contrast to a reference to a BDD in the representation without use of complemented edges, which is the root node of the BDD. The reason why a reference in this representation needs to be an edge is that for each Boolean function, the function and its negation are represented by an edge to the root of a BDD, and a complemented edge to the root of the same BDD. This is why negation takes constant time. It also explains why a single leaf node suffices: FALSE is represented by a complemented edge that points to the leaf node, and TRUE is represented by an ordinary edge (i.e., not complemented) that points to the leaf node.

For example, assume that a Boolean function is represented with a BDD represented using complemented edges. To find the value of the Boolean function for a given assignment of (Boolean) values to the variables, we start at the reference edge, which points to the BDD's root, and follow the path that is defined by the given variable values (following a low edge if the variable that labels a node equals FALSE, and following the high edge if the variable that labels a node equals TRUE), until we reach the leaf node. While following this path, we count how many complemented edges we have traversed. If when we reach the leaf node we have crossed an odd number of complemented edges, then the value of the Boolean function for the given variable assignment is FALSE, otherwise (if we have crossed an even number of complemented edges), then the value of the Boolean function for the given variable assignment is TRUE.

An example diagram of a BDD in this representation is shown on the right, and represents the same Boolean expression as shown in diagrams above, i.e., . Low edges are dashed, high edges solid, and complemented edges are signified by a circle at their source. The node with the @ symbol represents the reference to the BDD, i.e., the reference edge is the edge that starts from this node.

History

[edit]The basic idea from which the data structure was created is the Shannon expansion. A switching function is split into two sub-functions (cofactors) by assigning one variable (cf. if-then-else normal form). If such a sub-function is considered as a sub-tree, it can be represented by a binary decision tree. Binary decision diagrams (BDDs) were introduced by C. Y. Lee,[6] and further studied and made known by Sheldon B. Akers[7] and Raymond T. Boute.[8] Independently of these authors, a BDD under the name "canonical bracket form" was realized Yu. V. Mamrukov in a CAD for analysis of speed-independent circuits.[9] The full potential for efficient algorithms based on the data structure was investigated by Randal Bryant at Carnegie Mellon University: his key extensions were to use a fixed variable ordering (for canonical representation) and shared sub-graphs (for compression). Applying these two concepts results in an efficient data structure and algorithms for the representation of sets and relations.[10][11] By extending the sharing to several BDDs, i.e. one sub-graph is used by several BDDs, the data structure Shared Reduced Ordered Binary Decision Diagram is defined.[2] The notion of a BDD is now generally used to refer to that particular data structure.

In his video lecture Fun With Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs),[12] Donald Knuth calls BDDs "one of the only really fundamental data structures that came out in the last twenty-five years" and mentions that Bryant's 1986 paper was for some time one of the most-cited papers in computer science.

Adnan Darwiche and his collaborators have shown that BDDs are one of several normal forms for Boolean functions, each induced by a different combination of requirements. Another important normal form identified by Darwiche is decomposable negation normal form or DNNF.

Applications

[edit]BDDs are extensively used in CAD software to synthesize circuits (logic synthesis) and in formal verification. There are several lesser known applications of BDD, including fault tree analysis, Bayesian reasoning, product configuration, and private information retrieval.[13][14][citation needed]

Every arbitrary BDD (even if it is not reduced or ordered) can be directly implemented in hardware by replacing each node with a 2 to 1 multiplexer; each multiplexer can be directly implemented by a 4-LUT in a FPGA. It is not so simple to convert from an arbitrary network of logic gates to a BDD[citation needed] (unlike the and-inverter graph).

BDDs have been applied in efficient Datalog interpreters.[15]

Variable ordering

[edit]The size of the BDD is determined both by the function being represented and by the chosen ordering of the variables. There exist Boolean functions for which depending upon the ordering of the variables we would end up getting a graph whose number of nodes would be linear (in n) at best and exponential at worst (e.g., a ripple carry adder). Consider the Boolean function Using the variable ordering , the BDD needs nodes to represent the function. Using the ordering , the BDD consists of nodes.

|

|

It is of crucial importance to care about variable ordering when applying this data structure in practice. The problem of finding the best variable ordering is NP-hard.[16] For any constant c > 1 it is even NP-hard to compute a variable ordering resulting in an OBDD with a size that is at most c times larger than an optimal one.[17] However, there exist efficient heuristics to tackle the problem.[18]

There are functions for which the graph size is always exponential—independent of variable ordering. This holds e.g. for the multiplication function.[1] In fact, the function computing the middle bit of the product of two -bit numbers does not have an OBDD smaller than vertices.[19] (If the multiplication function had polynomial-size OBDDs, it would show that integer factorization is in P/poly, which is not known to be true.[20]) Another notorious example is the hidden weight bit function, regarded as the simplest function with an exponential-sized BDD.[21]

Researchers have suggested refinements on the BDD data structure giving way to a number of related graphs, such as BMD (binary moment diagrams), ZDD (zero-suppressed decision diagrams), FBDD (free binary decision diagrams), FDD (functional decision diagrams), PDD (parity decision diagrams), and MTBDDs (multiple terminal BDDs).

Logical operations on BDDs

[edit]Many logical operations on BDDs can be implemented by polynomial-time graph manipulation algorithms:[22]: 20

However, repeating these operations several times, for example forming the conjunction or disjunction of a set of BDDs, may in the worst case result in an exponentially big BDD. This is because any of the preceding operations for two BDDs may result in a BDD with a size proportional to the product of the BDDs' sizes, and consequently for several BDDs the size may be exponential in the number of operations. Variable ordering needs to be considered afresh; what may be a good ordering for (some of) the set of BDDs may not be a good ordering for the result of the operation. Also, since constructing the BDD of a Boolean function solves the NP-complete Boolean satisfiability problem and the co-NP-complete tautology problem, constructing the BDD can take exponential time in the size of the Boolean formula even when the resulting BDD is small.

Computing existential abstraction over multiple variables of reduced BDDs is NP-complete.[23]

Model-counting, counting the number of satisfying assignments of a Boolean formula, can be done in polynomial time for BDDs. For general propositional formulas the problem is ♯P-complete and the best known algorithms require an exponential time in the worst case.

See also

[edit]- Boolean satisfiability problem, the canonical NP-complete computational problem

- L/poly, a complexity class that strictly contains the set of problems with polynomially sized BDDs[citation needed]

- Model checking

- Radix tree

- Barrington's theorem

- Hardware acceleration

- Karnaugh map, a method of simplifying Boolean algebra expressions

- Zero-suppressed decision diagram

- Algebraic decision diagram, a generalization of BDDs from two-element to arbitrary finite sets

- Sentential Decision Diagram, a generalization of OBDDs

- Influence diagram

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bryant, Randal E. (August 1986). "Graph-Based Algorithms for Boolean Function Manipulation" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-35 (8): 677–691. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.2952. doi:10.1109/TC.1986.1676819. S2CID 10385726.

- ^ a b Brace, Karl S.; Rudell, Richard L.; Bryant, Randal E. (1990). "Efficient Implementation of a BDD Package". Proceedings of the 27th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC 1990). IEEE Computer Society Press. pp. 40–45. doi:10.1145/123186.123222. ISBN 978-0-89791-363-8.

- ^ Somenzi, Fabio (1999). "Binary decision diagrams" (PDF). Calculational system design. NATO Science Series F: Computer and systems sciences. Vol. 173. IOS Press. pp. 303–366. ISBN 978-90-5199-459-9.

- ^ Jean-Christophe Madre; Jean-Paul Billon (1988). "Proving Circuit Correctness Using Formal Comparison Between Expected and Extracted Behaviour". Proceedings of the 25th ACM/IEEE Conference on Design Automation, DAC '88, Anaheim, CA, USA, June 12-15, 1988. pp. 205–210. doi:10.1109/DAC.1988.14759. ISBN 0-8186-0864-1.

- ^ Knuth, D.E. (2009). Fascicle 1: Bitwise tricks & techniques; Binary Decision Diagrams. The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 4. Addison–Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-58050-4. Draft of Fascicle 1b Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine available for download

- ^ Lee, C.Y. (1959). "Representation of Switching Circuits by Binary-Decision Programs". Bell System Technical Journal. 38 (4): 985–999. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1959.tb01585.x.

- ^ Akers, Jr., Sheldon B (June 1978). "Binary Decision Diagrams". IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-27 (6): 509–516. doi:10.1109/TC.1978.1675141. S2CID 21028055.

- ^ Boute, Raymond T. (January 1976). "The Binary Decision Machine as a programmable controller". EUROMICRO Newsletter. 1 (2): 16–22. doi:10.1016/0303-1268(76)90033-X.

- ^ Mamrukov, Yu. V. (1984). Analysis of aperiodic circuits and asynchronous processes (PhD). Leningrad Electrotechnical Institute.

- ^ Bryant., Randal E. (1986). "Graph-Based Algorithms for Boolean Function Manipulation" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-35 (8): 677–691. doi:10.1109/TC.1986.1676819. S2CID 10385726.

- ^ Bryant, Randal E. (September 1992). "Symbolic Boolean Manipulation with Ordered Binary Decision Diagrams". ACM Computing Surveys. 24 (3): 293–318. doi:10.1145/136035.136043. S2CID 1933530.

- ^ "Stanford Center for Professional Development". scpd.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ^ Jensen, R.M. (2004). "CLab: A C++ library for fast backtrack-free interactive product configuration". Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3258. Springer. p. 816. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30201-8_94. ISBN 978-3-540-30201-8.

- ^ Lipmaa, H.L. (2009). "First CPIR Protocol with Data-Dependent Computation" (PDF). International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5984. Springer. pp. 193–210. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14423-3_14. ISBN 978-3-642-14423-3.

- ^ Whaley, John; Avots, Dzintars; Carbin, Michael; Lam, Monica S. (2005). "Using Datalog with Binary Decision Diagrams for Program Analysis". In Yi, Kwangkeun (ed.). Programming Languages and Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3780. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 97–118. doi:10.1007/11575467_8. ISBN 978-3-540-32247-4. S2CID 5223577.

- ^ Bollig, Beate; Wegener, Ingo (September 1996). "Improving the Variable Ordering of OBDDs Is NP-Complete". IEEE Transactions on Computers. 45 (9): 993–1002. doi:10.1109/12.537122.

- ^ Sieling, Detlef (2002). "The nonapproximability of OBDD minimization". Information and Computation. 172 (2): 103–138. doi:10.1006/inco.2001.3076.

- ^ Rice, Michael. "A Survey of Static Variable Ordering Heuristics for Efficient BDD/MDD Construction" (PDF).

- ^ Woelfel, Philipp (2005). "Bounds on the OBDD-size of integer multiplication via universal hashing". Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 71 (4): 520–534. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.138.6771. doi:10.1016/j.jcss.2005.05.004.

- ^ Richard J. Lipton. "BDD's and Factoring". Gödel's Lost Letter and P=NP, 2009.

- ^ Méaux, Pierrick; Seuré, Tim; Deng, Tang (2024). "The Revisited Hidden Weight Bit Function" (PDF). IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive: 24. Retrieved 2025-06-19.

- ^ Andersen, H. R. (1999). "An Introduction to Binary Decision Diagrams" (PDF). Lecture Notes. IT University of Copenhagen.

- ^ Huth, Michael; Ryan, Mark (2004). Logic in computer science: modelling and reasoning about systems (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–. ISBN 978-0-52154310-1. OCLC 54960031.

Further reading

[edit]- Ubar, R. (1976). "Test Generation for Digital Circuits Using Alternative Graphs". Proc. Tallinn Technical University (in Russian) (409). Tallinn, Estonia: 75–81.

- Meinel, C.; Theobald, T. (2012) [1998]. Algorithms and Data Structures in VLSI-Design: OBDD – Foundations and Applications (PDF). Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-58940-9. Complete textbook available for download.

- Ebendt, Rüdiger; Fey, Görschwin; Drechsler, Rolf (2005). Advanced BDD optimization. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-25453-1.

- Becker, Bernd; Drechsler, Rolf (1998). Binary Decision Diagrams: Theory and Implementation. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-5047-5.

External links

[edit]- Fun With Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs), lecture by Donald Knuth

- List of BDD software libraries for several programming languages.

Binary decision diagram

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A binary decision diagram (BDD) is a rooted, directed acyclic graph (DAG) used to represent a Boolean function of n variables, where the vertex set consists of nonterminal vertices (decision nodes) and terminal vertices. Each decision node is labeled with a variable index v from the set {1, ..., n} and has two outgoing edges: a low edge (labeled 0) to the child low(v) and a high edge (labeled 1) to the child high(v), both of which are other vertices in the graph. The terminal vertices are labeled with values 0 (false) or 1 (true), and no decision node points to itself or creates a cycle, ensuring the acyclic property.[5] The structure of a BDD is recursively defined based on the Shannon expansion theorem, which decomposes a Boolean function f(x_1, ..., x_n) at variable x_i as: where denotes the negation of x_i, and is the cofactor of f with x_i fixed to b ∈ {0,1}. This expansion corresponds to traversing the low or high edge from the decision node for x_i, leading to subgraphs representing the cofactors, until reaching a terminal node that evaluates the function for a given input assignment.[5] A specific form known as the reduced ordered binary decision diagram (ROBDD) imposes two key restrictions: variables appear in a fixed linear order along any path from root to terminal (ordered), and no decision node has identical low and high children, with isomorphic subgraphs shared to eliminate redundancy (reduced). Under a fixed variable ordering, ROBDDs provide a canonical representation, meaning that every Boolean function has a unique ROBDD, and two ROBDDs represent the same function if and only if they are isomorphic as graphs.[5] ROBDDs inherit basic properties from general BDDs, including that any Boolean function over a finite set of variables has a finite BDD representation, as the graph size is bounded by the number of possible subfunctions. Equivalent functions yield isomorphic BDDs, enabling efficient equivalence checking by structural comparison rather than exhaustive truth table evaluation.[5]Example

To illustrate the construction of a binary decision diagram (BDD), consider the three-variable Boolean function representing odd parity, , where the prime denotes negation. This function evaluates to true for input combinations with an odd number of 1s: specifically, the minterms 001, 010, 100, and 111. Assume a fixed variable ordering , meaning decisions are made first on , then , and finally . The BDD is built recursively via Shannon decomposition: , where and are the cofactors obtained by substituting and , respectively. The cofactor . Decomposing further on : and . Thus, the low branch from the root -node leads to a -node whose low child is a -node (low edge to 0-terminal, high to 1-terminal) and high child is a -node (low to 1-terminal, high to 0-terminal). The cofactor (where denotes XNOR). Decomposing on : and . Thus, the high branch from the root leads to another -node whose low child is the -node and high child is the -node. In the resulting diagram, the root is an -node with a low edge to one -node and a high edge to a distinct -node. These -nodes branch to shared - and -nodes, which connect to the 0- and 1-terminals. Path compression occurs through subgraph sharing: the -node (low: 0, high: 1) and -node (low: 1, high: 0) are common substructures referenced by both -nodes, avoiding duplication. Each path from the root to a 1-terminal corresponds to a minterm of the function. For instance, the path root -low → -low → -high traces the assignment (minterm ), while root -high → -high → -high traces (minterm ). Paths to the 0-terminal represent the complementary minterms (000, 011, 101, 110). This path-based evaluation directly encodes the function's truth table in graphical form. Before reduction, the full decision tree would require 7 non-terminal nodes (1 for , 2 for , 4 for ) due to separate copies of the terminal subtrees under each branch. After applying reduction rules—eliminating duplicate subgraphs—the shared - and -nodes reduce the non-terminal count to 5 (1 -node, 2 -nodes, 2 -nodes), plus 2 terminals, demonstrating how BDDs compactly represent the function through isomorphism detection.Variants

Reduced Ordered BDDs

An ordered binary decision diagram (OBDD) is a binary decision diagram in which the variables appear in a fixed linear order along each path from the root to a leaf, with no variable repeating on any path. This ordering ensures that the decision nodes for each variable are encountered in a consistent sequence, typically indexed from 1 to n for n variables, where the index of a node is strictly less than the indices of its children.[5] To achieve a canonical representation, OBDDs are reduced by applying two key rules: first, merging any isomorphic subgraphs, meaning distinct nodes with identical structures and labels (including child pointers) are replaced by a single shared node; second, eliminating redundant nodes where the low and high children are the same, as such a node does not depend on its variable and can be bypassed. These reductions transform the OBDD into a directed acyclic graph that is minimal in size while preserving the represented Boolean function. The resulting structure, known as a reduced ordered binary decision diagram (ROBDD), ensures no further applications of these rules are possible.[5] A fundamental property of ROBDDs is their uniqueness: for a given variable ordering, every Boolean function has exactly one ROBDD representation, up to isomorphism. This canonical form implies that two ROBDDs represent the same function if and only if their root nodes are identical, as the reduction process eliminates all non-canonical variations. Formally, if and are Boolean functions with ROBDDs having roots and , then if . This theorem enables efficient equivalence checking by simple pointer comparison rather than full function evaluation.[5]Complemented Edge BDDs

Complemented edge binary decision diagrams (BDDs) extend reduced ordered BDDs by incorporating complemented edges, where the low (0) edge from a node can be marked as complemented, often denoted as , to represent the negation of the subfunction it points to. This feature allows a single subgraph to represent both a Boolean function and its complement, avoiding the need for duplicate structures in standard BDDs.[6] The negation operation on a complemented edge BDD is performed in constant time by inverting the complement attribute at the root node, which effectively flips the polarity of the entire represented function without reconstructing the diagram. Modified reduction rules ensure canonicity: during the isomorphism check, subgraphs are considered equivalent if they match exactly or if one is the complement of the other, eliminating redundant nodes and obviating the need for a separate negative terminal—only the positive terminal (1) is required, with represented via a complemented edge to it.[7] By enabling subgraph sharing for complementary functions, this variant improves space efficiency, potentially reducing the total number of nodes by up to a factor of two in representations involving frequent negations. In particular, for circuits with many XOR operations, which rely heavily on complements, complemented edge BDDs minimize duplication, leading to substantial memory savings during construction and manipulation.[6][8] For example, the ROBDD for a multiplexer function consists of a root node for with a high edge to and a low edge to . To represent the complement , the complemented edge variant simply applies a complement mark to the root's incoming edge, inverting the polarity and reusing the same subgraph structure without additional nodes.[7]Multiterminal and Zero-Suppressed BDDs

Multiterminal binary decision diagrams (MTBDDs) extend standard binary decision diagrams by allowing terminal nodes to hold arbitrary values, such as integers or real numbers, rather than just 0 or 1. This generalization enables the compact representation of multi-output Boolean functions, arithmetic circuits, and matrix operations, where the value at each terminal corresponds to the function's output for a given input path. For instance, MTBDDs can efficiently encode the weights or coefficients in polynomial expressions or the entries in dense matrices, leveraging the shared substructure of decision diagrams to reduce storage. The structure maintains the ordered variable traversal of reduced ordered BDDs (ROBDDs) but replaces the binary terminals with a finite set of distinct values, ensuring uniqueness through reduction rules that eliminate redundant nodes where both children are identical. Zero-suppressed binary decision diagrams (ZDDs) represent a variant optimized for encoding families of sparse sets or combinations, such as subsets in combinatorial problems, by applying a specialized reduction rule. In ZDDs, a node for variable is deleted if its low child (corresponding to ) points to the zero-terminal, preventing the representation of paths that exclude elements unless necessary. This rule contrasts with standard BDD reduction, which skips nodes only when low and high children are identical, allowing ZDDs to compactly store sparse structures like all -subsets of an -element set without enumerating dense Boolean functions. The resulting diagram is isomorphic to the set family it represents, with paths from root to the one-terminal corresponding exactly to valid combinations.[9] The key differences between MTBDDs and ZDDs lie in their terminal semantics and reduction strategies: MTBDDs generalize to non-binary values for multi-valued functions while preserving Boolean-like operations, whereas ZDDs modify the suppression rule to eliminate zero-low nodes, enabling efficient subset enumeration and manipulation without the overhead of representing absent elements. This distinction makes ZDDs particularly suited for set-theoretic operations, such as union or intersection of combinatorial families, where the diagram size scales logarithmically with the number of sets rather than exponentially. In contrast to complemented-edge BDDs, which optimize binary negation, both MTBDDs and ZDDs address non-standard domains—multi-output or sparse—by altering terminal handling and node elimination criteria.[10] Recent advancements since 2020 have applied MTBDDs to quantum circuit simulation. For example, MTBDD-based simulators with symbolic execution and loop summarization accelerate the evaluation of quantum gate operations, achieving several orders of magnitude speedup on iterative circuits like Grover's algorithm compared to state-of-the-art simulators.[11]Historical Development

Origins and Early Work

The foundational concepts underlying binary decision diagrams emerged from early work in switching theory, particularly Claude Shannon's 1938 master's thesis, "A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits." In this work, Shannon applied Boolean algebra to model the behavior of relay networks symbolically, demonstrating how switching functions could be analyzed and synthesized using logical expressions rather than physical trial-and-error. This approach provided the theoretical groundwork for decomposing Boolean functions into decision-based structures, influencing subsequent graphical representations of logic circuits.[12] A significant advancement came in 1959 with C. Y. Lee's invention of binary-decision programs, the first explicit structure resembling a binary decision diagram, designed for minimizing relay contact networks in switching circuits. Lee's method represented a switching function as a binary tree, where each internal node tests a binary variable (e.g., a contact's state), with branches leading to sub-programs that resolve the function recursively until reaching a terminal decision (true or false). This tree-based approach enabled systematic enumeration of contact configurations and optimization for minimal series-parallel networks, offering a practical tool for circuit design at Bell Laboratories.[13] Early binary-decision structures, including Lee's programs, suffered from key limitations: they lacked mechanisms for sharing common subgraphs across branches, resulting in redundant computations and exponential space complexity for functions with many variables, particularly without a consistent variable ordering to guide the decomposition.[14] Preceding modern refinements, S. B. Akers advanced these ideas in 1978 with his introduction of binary decision diagrams as graphical models for digital functions, emphasizing path-based representations that allowed multiple paths to converge on shared decision points. Akers' diagrams served as direct precursors to shared directed acyclic graphs, facilitating analysis and functional testing of combinational logic while highlighting the potential for compact representations despite persistent space challenges in unrestricted forms.[3]Modern Advancements

A pivotal advancement in the field of binary decision diagrams (BDDs) came in 1986 with Randal E. Bryant's introduction of reduced ordered BDDs (ROBDDs), which impose a fixed variable ordering and ensure unique representation of subgraphs through sharing and reduction rules. This structure allows for canonical representations of Boolean functions, enabling manipulation operations such as conjunction and quantification to be performed in polynomial time relative to the size of the diagram.[5] In the 1990s, extensions broadened the applicability of BDDs. Complemented edges were introduced in 1990 by Brace, Rudell, and Bryant, permitting efficient representation of function negations by marking edges without duplicating nodes, thereby reducing memory usage by up to a factor of two while maintaining constant-time negation. Multi-terminal BDDs (MTBDDs), proposed by Coudert et al. in 1993, generalize BDDs to represent multi-valued functions and matrices by allowing multiple terminals, facilitating applications in numerical computations and algebraic manipulations. Similarly, zero-suppressed BDDs (ZDDs), developed by Minato in 1993, optimize for sparse sets by suppressing nodes where the zero-child leads to the zero function, enhancing compactness for combinatorial problems. From the 2000s to the 2020s, BDDs integrated with other paradigms, including Boolean satisfiability (SAT) solvers, as exemplified by McMillan's 2003 work combining BDDs with CNF representations for hybrid solving in verification tasks.[15] In quantum computing, decision diagrams evolved into variants like quantum MDDs (QMDDs) by Miller and Thornton in 2006. A notable 2024 contribution by Méaux and Seuré revisited the hidden weight bit function (HWBF), a benchmark for BDD complexity, proposing a quadratic variant with enhanced cryptographic resistance while preserving high BDD sizes against structural attacks.[16] These developments marked a shift from theoretical constructs to practical tools in electronic design automation (EDA), where BDDs underpin model checking and synthesis in industry-standard flows. Ongoing research focuses on scalable variants, such as multi-core implementations like HermesBDD by Capogrosso et al. in 2023, to handle big data challenges in verification of large-scale systems.[17]Construction and Operations

Building BDDs

Binary decision diagrams (BDDs) are constructed from Boolean expressions or truth tables using algorithms that leverage the Shannon expansion theorem, which decomposes a function with respect to a variable as , where denotes the cofactor obtained by setting . This recursive decomposition forms the basis for building the diagram top-down, starting from the root variable and proceeding to terminal nodes (0 or 1). The process ensures sharing of subgraphs through memoization, avoiding redundant computations.[5] The core of the recursive construction is the If-Then-Else (ITE) operator, defined as , which directly corresponds to the Shannon expansion for variable . To build a BDD for a function , the algorithm recursively applies ITE: if is constant, return the terminal node; otherwise, select the next variable in the ordering, compute the BDDs for the cofactors and , and create a new decision node with low child , high child , and variable . A unique table, typically implemented as a hash table mapping triples to existing nodes, enforces sharing and reduction by returning a preexisting node if one matches, or inserting a new one otherwise. This top-down approach has a time complexity bounded by the size of the resulting BDD, often in the worst case for variables, but efficient in practice due to memoization.[5] The following pseudocode outlines the recursive build function for a Boolean expression, assuming a fixed variable ordering and access to the unique table:function Build(f, vars):

if f is constant c:

return terminal(c)

if f is already memoized:

return memo[f]

xi = next variable in vars for f

f1 = Build(f|_{xi=1}, vars)

f0 = Build(f|_{xi=0}, vars)

node = UniqueTable.lookup(xi, f0, f1)

if node is null:

node = new Node(xi, f0, f1)

UniqueTable.insert(xi, f0, f1, node)

memo[f] = node

return node

function Build(f, vars):

if f is constant c:

return terminal(c)

if f is already memoized:

return memo[f]

xi = next variable in vars for f

f1 = Build(f|_{xi=1}, vars)

f0 = Build(f|_{xi=0}, vars)

node = UniqueTable.lookup(xi, f0, f1)

if node is null:

node = new Node(xi, f0, f1)

UniqueTable.insert(xi, f0, f1, node)

memo[f] = node

return node