Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Factory Records

View on Wikipedia

Factory Records was a Manchester-based British independent record label founded in 1978 by Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus.

Key Information

The label featured several important acts on its roster, including Joy Division, New Order, A Certain Ratio, the Durutti Column, Happy Mondays, Northside, and (briefly) Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark and James. Factory also ran The Haçienda nightclub, in partnership with New Order.

Factory Records used a creative team (most notably record producer Martin Hannett and graphic designer Peter Saville) which gave the label and the artists recording for it a particular sound and image. The label employed a unique cataloguing system that gave a number not just to its musical releases, but also to various other related miscellany, including artwork, films, living beings, and even Wilson's own coffin.[1]

History

[edit]'The Factory'

[edit]The Factory name was first used for a club in May 1978; the first Factory night was on the 26 May 1978.[2] The club became a Manchester legend in its own right, being known variously as the Russell Club, Caribbean Club, PSV (Public Service Vehicles) Club (so titled as it was originally a social club for bus drivers[3] who worked from the nearby depot) and 'The Factory'.[4] The 'Factory' night at The Russell Club was launched by Alan Erasmus, Tony Wilson, and helped by promoter Alan Wise. As well as attracting numerous touring bands to the area and many upcoming post punk bands,[4] it featured local bands including the Durutti Column (managed at the time by Erasmus and Wilson), Cabaret Voltaire from Sheffield and Joy Division.[5] The club was demolished in 2001.[6] The club was located on the NE corner of the now demolished Hulme Crescents development,[7] on the corner of Royce Rd and Clayburn St (53°28′04.5″N 2°15′00.2″W / 53.467917°N 2.250056°W). Peter Saville designed advertising for the club, and in September Factory released an EP of music by acts who had played at the club (the Durutti Column, Joy Division, Cabaret Voltaire and comedian John Dowie) called A Factory Sample.[8]

1978 and 1979

[edit]As a follow-on from the successful 'Factory Nights' held at the Russell Club, Factory Records made their first release, A Factory Sample, in January 1979.[5][9] At that time there was a punk label in Manchester called Rabid Records, run by Tosh Ryan and Martin Hannett. It had several successful acts, including Slaughter & the Dogs (whose tour manager was Rob Gretton), John Cooper Clarke, and Jilted John. After his seminal TV series So It Goes, Tony Wilson was interested in the way Rabid Records ran, and was convinced that the real money and power were in album sales. With a lot of discussion, Tony Wilson, Rob Gretton and Alan Erasmus set up Factory Records, with Martin Hannett from Rabid.[10]

In 1978, Wilson compered the new wave afternoon at Deeply Vale Festival. This was actually the fourth live appearance by the fledgling Durutti Column and that afternoon Wilson also introduced an appearance (very early in their career) by the Fall, featuring Mark E. Smith and Marc "Lard" Riley on bass guitar.[11]

The Factory label set up an office in Erasmus' home on the first floor of 86 Palatine Road (53°25′38.0″N 2°14′06.2″W / 53.427222°N 2.235056°W), and the Factory Sample EP was released on 24 December 1978. Singles followed by A Certain Ratio (who would stay with the label) and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (who left for Virgin Records shortly afterwards). The first Factory LP, Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures, was released in June 1979.[12]

1980s

[edit]In January 1980, The Return of the Durutti Column was released, the first in a long series of releases by guitarist Vini Reilly. In May, Joy Division singer Ian Curtis committed suicide shortly before a planned tour of the US. The following month saw Joy Division's single "Love Will Tear Us Apart" reach the UK top twenty, and their second album Closer was released the following month. In late 1980, the remaining members of Joy Division decided to continue as New Order. Factory branched out, with Factory Benelux being run as an independent label in conjunction with Les Disques du Crepuscule, and Factory US organising distribution for the UK label's releases in America.[13]

In 1981, Factory and New Order opened a nightclub and preparations were made to convert a Victorian textile factory near the centre of Manchester, which had lately seen service as a motor boat showroom. Hannett left the label, as he had wanted to open a recording studio instead, and subsequently sued for unpaid royalties (the case was settled out of court in 1984). Saville also quit as a partner due to problems with payments, although he continued to work for Factory. Wilson, Erasmus and Gretton formed Factory Communications Ltd.[14]

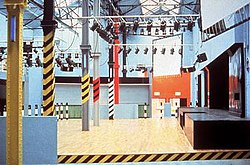

The Haçienda (FAC 51) opened in May 1982.[15][16] Although successful in terms of attendance, and attracting a lot of praise for Ben Kelly's interior design, the club lost large amounts of money in its first few years due largely to the low prices charged for entrance and at the bar, which was markedly cheaper than nearby pubs. Adjusting bar prices failed to help matters as crowds were increasingly preferring ecstasy to alcohol by the mid-1980s. Therefore, the Haçienda ended up costing tens of thousands of pounds every month.[9]

In 1983, New Order's "Blue Monday" (FAC 73) became an international chart hit.[17] However, the label did not make any money from it since the original sleeve, die-cut and designed to look like a floppy disk, was so costly to make that the label lost £0.05 (equivalent to £0.21 in 2023) on every copy they sold.[14][18] Saville noted that nobody at Factory expected "Blue Monday" to be a commercially successful record at all, so nobody expected the cost to be an issue.[19]

Happy Mondays released their first album in 1985. New Order and Happy Mondays became the most successful bands on the label, bankrolling a host of other projects.[14] Factory and the Haçienda became a cultural hub of the emerging techno and acid house genres and their amalgamation with post-punk guitar music (the "Madchester" scene). Mick Middles' book Joy Division to New Order published in 1986 by Virgin Books (later being reprinted under the title Factory). In 1989, the label extended its reach to fringe punk folk outfit To Hell With Burgundy. Factory also opened a bar (The Dry Bar, FAC 201) and a shop (The Area, FAC 281) in the Northern Quarter of Manchester.[13]

1990s

[edit]Factory's headquarters (FAC 251) on Charles Street, near the Oxford Road BBC building, were opened in September 1990; prior to this, the company was still registered at Alan Erasmus' flat in Didsbury.[citation needed]

In 1991, Factory suffered two tragedies: the deaths of Martin Hannett and Dave Rowbotham. Hannett had recently re-established a relationship with the label, working with Happy Mondays, and tributes including a compilation album and a festival were organised. Rowbotham was one of the first musicians signed by the label; he was an original member of the Durutti Column and shared the guitar role with Vini Reilly; he was murdered and his body was found in his flat in Burnage.[20] Saville's association with Factory was now reduced to simply designing for New Order and their solo projects (the band itself was in suspension, with various members recording as Electronic, Revenge and the Other Two).

By 1992, the label's two most successful bands caused the label serious financial trouble. The Happy Mondays were recording their troubled fourth album Yes Please! in Barbados, and New Order reportedly spent £400,000 on recording their comeback album Republic. London Records were interested in taking over Factory but the deal fell through when it emerged that, due to Factory's early practice of eschewing contracts, New Order rather than the label owned New Order's back catalogue.[9]

Factory Communications Ltd, the company formed in 1981, declared bankruptcy in November 1992. Many former Factory acts, including New Order, found a new home at London Records.[9]

The Haçienda closed in 1997 and the building was demolished shortly afterwards. It was replaced by a modern luxury apartment block in 2003, also called The Haçienda.[21] In October 2009, Peter Hook published his book on his time as co-owner of the Haçienda, How Not to Run a Club, and in 2010 he had six bass guitars made using wood from the Haçienda's dancefloor.[22][23][24]

2000s

[edit]

The 2002 film 24 Hour Party People is centred on Factory Records, the Haçienda, and the infamous, often unsubstantiated anecdotes and stories surrounding them. Many of the people associated with Factory, including Tony Wilson, have minor parts; the central character, based on Wilson, is played by actor and comedian Steve Coogan.[25]

Anthony Wilson, Factory Records' founder, died on 10 August 2007 at age 57, from complications arising from renal cancer.[26]

Colin Sharp, the Durutti Column singer during 1978 who took part in the A Factory Sample EP, died on 7 September 2009, after suffering a brain haemorrhage. Although his involvement with Factory was brief, Sharp was an associate for a short while of Martin Hannett and wrote a book called Who Killed Martin Hannett,[27] which upset Hannett's surviving relatives, who stated the book included numerous untruths and fiction. Only months after Sharp's death, Larry Cassidy, Section 25's bassist and singer, died of unknown causes, on 27 February 2010.[28]

In early 2010, Peter Hook, in collaboration with the Haçienda's original interior designer Ben Kelly and British audio specialists Funktion-One, renovated and reopened FAC 251 (the former Factory Records headquarters on Charles Street) as a nightclub.[5] The club still holds its original name, FAC 251, but people refer to it as "Factory". Despite Ben Kelly's design influences, Peter Hook insists, "It's not the Haçienda for fucks [sic] sake". The club has a weekly agenda, featuring DJs and live bands of various genres.[5]

In May 2010, James Nice, owner of LTM Recordings, published the book Shadowplayers. The book charts the rise and fall of Factory and offers detailed accounts and information about many key figures involved with the label.[29]

FAC numbers

[edit]Musical releases, and essentially anything closely associated with the label, were given a catalogue number in the form of either FAC, or FACT, followed by a number. FACT was reserved for full-length albums, while FAC was used for both single song releases and many other Factory "productions", including: posters (FAC 1 advertised a club night), The Haçienda (FAC 51), a lawsuit filed against Factory Records by Martin Hannett (FAC 61),[30] a hairdressing salon (FAC 98), a broadcast of Channel 4's The Tube TV series (FAC 104), customised packing tape (FAC 136), a bucket on a restored watermill (FAC 148), the Haçienda cat (FAC 191), a bet between Wilson and Gretton (FAC 253),[31] a radio advertisement (FAC 294), and a website (FAC 421).[32] Similar numbering was used for compact disc media releases (FACD), CD Video releases (FACDV), Factory Benelux releases (FAC BN or FBN), Factory US releases (FACTUS), and Gap Records Australia releases (FACOZ), with many available numbers restricted to record releases and other directly artist-related content.[33][13]

Numbers were not allocated in strict chronological order; numbers for Joy Division and New Order releases generally ended in 3, 5, or 0 (with most Joy Division and New Order albums featuring multiples of 25), A Certain Ratio and Happy Mondays in 2, and the Durutti Column in 4. Factory Classical releases were 226, 236 and so on.[33][13]

Despite the demise of Factory Records in 1992, the catalogue was still active. Additions included the 24 Hour Party People film (FAC 401), its website (FAC 433) and DVD release (FACDVD 424), and a book, Factory Records: The Complete Graphic Album (FAC 461).[33][13]

Even Tony Wilson's coffin received a Factory catalogue number; FAC 501.[34][13]

Factory Classical

[edit]In 1989, Factory Classical was launched with five albums by composer Steve Martland, the Kreisler String Orchestra, the Duke String Quartet (which included Durutti Column viola player John Metcalfe), oboe player Robin Williams and pianist Rolf Hind. Composers included Martland, Benjamin Britten, Paul Hindemith, Francis Poulenc, Dmitri Shostakovich, Michael Tippett, György Ligeti and Elliott Carter. Releases continued until 1992, including albums by Graham Fitkin, vocal duo Red Byrd, a recording of Erik Satie's Socrate, Piers Adams playing Handel's Recorder Sonatas, Walter Hus and further recordings both of Martland's compositions and of the composer playing Mozart.

Successor labels

[edit]In 1994, Wilson attempted to revive Factory Records, in collaboration with London Records, as "Factory Too". The first release was by Factory stalwarts the Durutti Column; the other main acts on the label were Hopper and Space Monkeys, and the label gave a UK release to the first album by Stephin Merritt's side project the 6ths, Wasps' Nests. A further release ensued: a compilation EP featuring previously unsigned Manchester acts East West Coast, the Orch, Italian Love Party, and K-Track. This collection of 8 tracks (2 per band) was simply entitled A Factory Sample Too (FACD2.02). The label was active until the late 1990s, latterly independent of London Records, as was "Factory Once", which organised reissues of Factory material.[13]

Wilson founded a short-lived fourth incarnation, F4 Records, in the early 2000s.[35]

In 2012, Peter Saville and James Nice formed a new company called Factory Records Ltd., in association with Alan Erasmus and Oliver Wilson (son of Tony). This released only a vinyl reissue of From the Hip by Section 25.[36] Nice subsequently revived the Factory Benelux imprint for Factory reissues, and for new recordings by Factory-associated bands.[37] In 2019, Warner Music Group marked the 40th anniversary of Factory as a record label with a website, exhibition, and select vinyl editions including Unknown Pleasures and box set compilation Communications 1978-1992.

Factory Records recording artists

[edit]The bands with the most numerous releases on Factory Records include Joy Division/New Order, Happy Mondays, Durutti Column and A Certain Ratio. Each of these bands has between 15 and 30 FAC numbers attributed to their releases.

Retrospective

[edit]An exhibition By Colin Gibbins took place celebrating the 20th anniversary of the closing of Factory Records (1978–1992) and its musical output, Colin's collection was displayed at the Ice Plant, Manchester, between 4 and 7 May 2012. The exhibition was called FACTVM (from the Latin for 'deed accomplished').[38][39]

In October 2019, a new box set was released containing both rarities and the label’s releases from its first two years.[40]

From 19 June 2021 until 3 January 2022, Manchester's Science and Industry Museum hosted an exhibition commemorating Factory Records entitled 'Use Hearing Protection: The early years of Factory Records' Featuring graphic designs by Peter Saville, previously unseen items from the Factory archives, and objects loaned from the estates of both Tony Wilson and Rob Gretton, the former manager of Joy Division and New Order.[41][42]

Further reading

[edit]- Golden, Audrey (4 May 2023). I Thought I Heard You Speak: Women at Factory Records. Orion. ISBN 978-1-3996-0620-2.

- Hook, Peter (1 October 2009). The Hacienda: How Not to Run a Club. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84737-847-7.

- Middles, Mick (11 July 2011). Factory: The Story of the Record Label. Random House. ISBN 978-0-7535-4754-0.

- Reade, Lindsay (15 August 2016). Mr Manchester and the Factory Girl: The Story of Tony and Lindsay Wilson. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85965-875-1.

- Robertson, Matthew (2007). Factory Records: The Complete Graphic Album. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28636-4.

- Nice, James (2010). Shadowplayers: The Rise and Fall of Factory Records. Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-540-9.

References

[edit]- ^ Lynskey, Dorian. "A fitting headstone for Tony Wilson's grave". The Guardian.

- ^ Charlton, Matt (27 September 2019). "Eight objects that tell the story of Factory Records' early days". Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Wright, Paul (27 May 2018). "No Place Like Hulme". British Culture Archive. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ a b "The Russell Club". Manchester Digital Music Archive.

- ^ a b c d "FAC251 Factory Manchester". Factory Manchester. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Artefact". Manchester Digital Music Archive. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "The Hulme Crescents". Manchester History. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Eight objects that tell the story of Factory Records' early days". Dazed. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d Nicolson, Barry (13 August 2015). "Why The Legacy Of Factory Records Boss Tony Wilson Can Still Be Felt Today". NME. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ McDonald, Heather. "Factory Records Profile". Factory Records. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Greene, Jo-Ann. "Live At Deeply Vale Review". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Macauley, Ray. "Pulsars, Pills, and Post-Punk". The Science And Entertainment Laboratory. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cooper, John (26 December 2014). "The Factory Records catalogue". Cerysmatic Design. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Factory Records – The Rise And Fall of UK's Legendary Indie Label". Live4ever. 22 November 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Kelly, Ben (21 May 2017). "Not the hippest bunch: Behind the scenes of the Hacienda's opening party". The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Jones, Josh (25 April 2020). "Opening Night at The Haçienda: New Order's Manchester Club Begins Its Legendary 15-Year Run in 1982". Flashbak. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Le Blanc, Ondine. "New Order". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Matthew Robertson (2007). Factory Records: The Complete Graphic Album. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-8118-5642-3.

- ^ "Design: Tony Wilson & Peter Saville In Conversation". 24 Hour Party People DVD commentary. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1995). Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Guinness Publications. p. 1274. ISBN 1-56159-176-9.

- ^ "Iconic Manchester nightclub the Hacienda recreated at Victoria and Albert Museum in London". Manchester Evening News. 28 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ "FAC 51 The Hacienda Limited Edition Peter Hook Bass Guitar". Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Ben Turner (12 January 2013). "Peter Hook's gig with bass guitar made from Hacienda floor". manchestereveningnews.

- ^ Rick Bowen (13 June 2013). "Altrincham shop lands rare guitar". messengernewspapers.co.uk.

- ^ "24 Hour Party People (2002) - IMDb". IMDb.com.

- ^ "Factory Records founder Anthony Wilson dies from cancer". Side-line.com. 10 August 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Staff (21 December 2007). "Zeroing in on Martin". BBC Manchester. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "The Independent - Obituaries: Larry Cassidy: Leader of the post-punk Factory group Section 25". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ "What Manchester learned from The Haçienda - 20 years on". Inews.co.uk. 18 July 2017.

- ^ BBC Film: Factory: From Joy Division to Happy Mondays

- ^ "Factory Records: FAC 253 Chairman Resigns". Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Tony (21 January 2004). "Signed FAC 421 confirmation card". Factory Communications Ltd. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Factory Records Profile". 20 March 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Dorian Lynskey (26 October 2010). "A fitting headstone for Tony Wilson's grave | Music". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Factory Records: F4 Records". Factoryrecords.org.

- ^ "Cerysmatic Factory: Section 25 FACT 90 From The Hip vinyl issue". News.cerysmaticfactory.info. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Cerysmatic Factory: A Factory Benelux Story". News.cerysmaticfactory.info. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ FACTVM 20th Anniversary Exhibition Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, PeterHook.co.uk, 11 April 2012. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ^ FACTVM Factory Records 1978-1992 Exhibition, 5-7 May 2012, Cerysmaticfactory.info. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ^ "Various Artists Use Hearing Protection: Factory Records 1978-79". Pitchfork.com. 20 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Factory records exhibition opens at Manchester's Science and Industry Museum". ITV News. 20 June 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Use Hearing Protection: The early years of Factory Records". Science and Industry Museum. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

External links

[edit]Factory Records

View on GrokipediaFounding and Early History

Origins in 'The Factory' Club

The Factory nightclub emerged in Manchester in May 1978 as a pivotal venue for the city's burgeoning post-punk and experimental music scene, founded by Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus.[3][4] The name "Factory" was suggested by Alan Erasmus after he saw a neon sign reading "Factory for Sale" while driving, and the club was established at the Russell Club in Hulme, transforming the space into a hub for avant-garde performances, art installations, and DJ sets that challenged conventional nightlife.[5] Wilson, an established Granada Television presenter known for his music program So It Goes, and Erasmus, an actor and musician, aimed to create a platform that prioritized cultural innovation over commercial gain, reflecting Manchester's industrial grit and creative rebellion.[6][4] Wilson's television role had already positioned him as a key promoter of the local punk movement, where he showcased emerging bands like the Buzzcocks on So It Goes, helping to ignite Manchester's punk explosion and connect it to broader national audiences.[6][7] This exposure fostered a vibrant ecosystem for underground acts, with the Factory club serving as a natural extension of Wilson's efforts to nurture the scene's raw energy and DIY ethos, drawing in performers and audiences eager for unfiltered artistic expression.[3] The club's early nights, starting around May 19, featured eclectic lineups that blended noise, performance art, and improvisation, cultivating an atmosphere of communal experimentation amid the venue's dimly lit, warehouse-like interior.[4][8] A landmark moment came in June 1978 when Joy Division headlined one of the club's initial events, marking their debut performance at the venue and underscoring its role in spotlighting Manchester's nascent post-punk talents.[9] This gig exemplified the club's influence, providing a stage for bands to refine their sound in front of receptive crowds and solidifying the Factory's reputation as a breeding ground for innovative music.[9] The transition toward a wider cultural initiative began with the involvement of designer Peter Saville, who created the promotional poster for the opening nights after being tipped off by Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon; this artwork, retrospectively cataloged as FAC 1, hinted at an emerging system for documenting the project's outputs.[4] Through such collaborations, the club evolved from a mere nightlife spot into the foundational element of a multifaceted arts enterprise.[10]Launch and Initial Releases (1978–1979)

Factory Records was formally established in late 1978 by Tony Wilson, a prominent Granada Television presenter known for his music show So It Goes, and Alan Erasmus, an actor and music enthusiast, as an independent record label based in Manchester, England. Martin Hannett, an experienced producer, joined as a partner and in-house producer, contributing his distinctive echo-laden sound that became synonymous with the label's output. Emerging directly from the Factory club nights—which Wilson and Erasmus had initiated earlier that year at the Russell Club in Hulme to showcase emerging local talent—the label aimed to capture and amplify the post-punk energy of the Manchester scene without the constraints of major industry players.[3][11][12] The label's inaugural musical release, the double 7-inch EP A Factory Sample (FAC 2), arrived in January 1979 and served as a manifesto for Factory's vision. Featuring contributions from Joy Division ("Digital" and "Glass"), The Durutti Column ("No Communication" and "Thin Ice (Detail)"), John Dowie (a comedy track), and Cabaret Voltaire ("Baader Meinhof" and "Sex in Secret"), the EP was recorded at Cargo Studios in Manchester and produced by Hannett, who emphasized atmospheric space and raw intensity in the recordings. Pressed in a limited run of 5,000 copies, its sleeve—designed by Peter Saville using translucent rice paper encased in a plastic bag—prioritized artistic innovation over standard packaging, setting a precedent for the label's aesthetic. This sampler played a pivotal role in the post-punk movement, introducing Joy Division's brooding sound to a wider audience and earning acclaim for its eclectic, forward-thinking curation that blended punk, industrial, and spoken word elements.[9][3] In May 1979, Factory followed with A Certain Ratio's debut EP All Night Party (FAC 5), a 7-inch single produced by Hannett that fused funk rhythms, angular guitars, and dub influences into a hypnotic post-punk groove. The release included "All Night Party" and "The Thin Boys," capturing the band's live energy from their Factory club performances; only 1,000 copies were pressed on deliberately low-fidelity vinyl, accompanied by a sticker declaring it a "limited edition on poor quality vinyl" to embrace punk's anti-perfectionist spirit. Though initial distribution was hampered by the label's independent status—relying on mail-order and select UK shops—the EP built a dedicated following and exemplified Factory's commitment to nurturing Manchester's experimental acts. Cabaret Voltaire's involvement in A Factory Sample further highlighted the label's early ties to industrial pioneers, with their abrasive tracks foreshadowing the genre's evolution.[3][9] From the outset, Factory operated on a radical business model that rejected traditional industry norms, forgoing formal contracts in favor of a "non-contract contract" that ensured artists retained ownership of their masters. Profits were split 50/50 between the label and artists after recouping costs, a structure Wilson championed to prioritize creative freedom over exploitation, though it created logistical hurdles in distribution and funding without major backing. This anti-commercial ethos, rooted in punk's DIY principles, positioned Factory as a haven for boundary-pushing music, even as early releases like A Factory Sample and All Night Party achieved modest sales but significant cultural impact within underground circles.[12][3]Growth in the 1980s

Key Artists and Successes

Factory Records signed Joy Division in late 1978, marking one of the label's earliest major commitments to a post-punk act with raw intensity and innovative production. Their debut album, Unknown Pleasures (FAC 10), released in June 1979 and produced by Martin Hannett, achieved modest initial sales of around 10,000 copies but garnered critical acclaim for its atmospheric sound and Peter Saville's iconic sleeve design. The follow-up, Closer (FAC 25), arrived in July 1980, shortly after frontman Ian Curtis's suicide in May of that year, which profoundly impacted the band's trajectory and elevated their mythic status in music history. Curtis's death not only halted Joy Division's live performances but also amplified the emotional resonance of their work, with Closer selling over 250,000 copies worldwide by 1982 and cementing the group's influence on alternative music.[13][14][15] Following Curtis's passing, the surviving members reformed as New Order in the summer of 1980, shifting Factory's sound toward electronic and dance influences inspired by New York club scenes. Their breakthrough single, Blue Monday (FAC 73), released in March 1983, became a global phenomenon despite its elaborate die-cut sleeve causing production losses; it sold over 1.16 million copies in the UK alone, making it the best-selling 12-inch single of all time. New Order's evolution peaked commercially with Technique (FAC 250), released in January 1989, which topped the UK Albums Chart—their first No. 1—and featured acid house elements, selling more than a million copies combined in the UK and US. This success was bolstered by international distribution deals, including a 1983 US partnership with Quincy Jones's Qwest Records for Power, Corruption & Lies, expanding Factory's reach beyond the UK indie scene.[13][16][17][18] Other pivotal acts contributed to Factory's 1980s roster, with A Certain Ratio delivering early funk-infused post-punk through albums like To Each (1981) and Sextet (1982), which explored Latin and dance rhythms and influenced later electronic acts. Factory also nurtured experimental acts like The Durutti Column, whose guitar-led ambient works such as LC (1981) exemplified the label's avant-garde ethos, and Cabaret Voltaire, whose industrial electronic albums like 2x45 (1980) expanded the roster's sonic diversity. Happy Mondays, signed in the mid-1980s as associates of New Order, built momentum with chaotic live shows and releases leading to their 1990 breakthrough Pills 'n' Thrills and Bellyaches (FAC 329), which peaked at No. 4 on the UK Albums Chart and achieved platinum status with over 300,000 UK sales, embodying the hedonistic baggy sound. The Haçienda nightclub, opened by Factory in May 1982 (FAC 51), played a crucial role in artist promotion and the emergence of the Madchester scene by the late 1980s, hosting rave nights that fused punk roots with acid house and drew crowds of up to 2,000, fostering a cultural hub for label acts amid Manchester's evolving music landscape. These developments underscored Factory's commercial zenith in the mid-1980s, with New Order's chart hits like Blue Monday reaching No. 12 in the UK (1983 release) and international licensing amplifying the label's global profile before financial strains emerged.[19][13][15][16]Innovations in Business and Design

Factory Records distinguished itself through groundbreaking approaches to visual design and business operations, prioritizing artistic expression over conventional commercial practices. As art director, Peter Saville crafted iconic album sleeves that elevated packaging to an integral part of the label's cultural output. For Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures (FAC 10, 1979), Saville employed a stark black-and-white image of radio waves from the pulsar CP 1919, resembling a tombstone or abstract waveform, sourced from an astronomical atlas to evoke themes of isolation and cosmic vastness.[20] Similarly, New Order's Power, Corruption & Lies (FAC 24, 1983) featured a reproduction of Henri Fantin-Latour's 19th-century painting A Basket of Roses, paired with a reverse-side color code wheel inspired by French color printing guides, symbolizing the album's exploration of societal themes while innovating in graphic reproduction techniques.[21] These designs often utilized experimental printing methods, such as thermographic embossing on early releases like Electricity (FAC 6, 1978), creating tactile, braille-like textures that challenged the era's standard glossy sleeves.[22] The label's anti-corporate philosophy further underscored its innovative ethos, rejecting traditional industry hierarchies in favor of collaborative equity. Founded by Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus, Factory operated without formal written contracts, relying instead on verbal agreements and a "gentleman's handshake" model that emphasized trust among partners.[23] Profits were shared equally—typically 50-50 splits—among artists, the label, and key collaborators like producer Martin Hannett, positioning Factory as a template for independent labels by ensuring creators retained ownership of their masters.[24] This approach, famously sealed in Wilson's blood on Joy Division's initial agreement, embodied a punk-inspired rejection of exploitative major-label deals, fostering an environment where artistic control trumped financial maximization.[23] Factory extended its creative numbering system, the FAC catalogue, beyond music to encompass merchandise and ephemera, blurring lines between art, product, and promotion. Every item, from records to club artifacts, received a unique FAC designation, treating non-musical outputs as equally significant cultural artifacts. For instance, posters and flyers for The Haçienda nightclub (FAC 51, opened 1982) were catalogued alongside releases, such as promotional materials featuring bold, minimalist graphics that reinforced the venue's industrial aesthetic.[22] This system also applied to clothing and other branded items, like T-shirts and bags, which carried FAC numbers to maintain a cohesive visual identity and commodify the label's ethos without diluting its artistic integrity.[25] Technological experimentation in production marked another pillar of Factory's innovations, particularly through Hannett's work at Strawberry Studios in Stockport. As the label's in-house producer, Hannett pioneered electronic sound manipulation, integrating early digital effects like the AMS DMX 15-80 delay unit to create expansive, reverberant drum sounds on Joy Division tracks such as "Digital."[26] His techniques embraced sampling precursors, using synthesizers like the ARP Omni-2 and Synare drum pads processed through fuzz boxes for metallic, industrial textures, as heard in "Atrocity Exhibition."[26] Sessions at Strawberry, often extending into all-night mixes, incorporated unconventional spaces for natural reverb—such as stairwells for echoes—while layering icy synthesizers and effected vocals to define post-punk's sonic landscape.[22] Hannett's vision even extended to advocating for a Fairlight CMI sampler for advanced electronic production, but financial constraints prevented its purchase.[22] These practices profoundly influenced independent label aesthetics, establishing a model where art superseded commerce and design became synonymous with identity. Factory's emphasis on high-cost, conceptual sleeves and equitable structures inspired subsequent indies like 4AD and Rough Trade, promoting a DIY visual language of die-cut packaging, overlaid photography, and regional symbolism that permeated 1980s post-punk and beyond.[25] By cataloguing everything from records to club nights under the FAC banner, the label cultivated a cult status, transforming Manchester into a global hub for innovative music culture and proving that anti-corporate ideals could yield enduring impact.[25]Challenges and Closure in the 1990s

Expansion to Factory Classical

In 1989, Factory Records expanded into classical music with the launch of its sub-label Factory Classical, spearheaded by co-founder Tony Wilson in partnership with John Metcalfe, a violinist and violist in the Factory-signed band The Durutti Column.[27][28] The initiative aimed to apply Factory's punk-inspired ethos of artistic freedom and innovative design to contemporary classical recordings, allowing musicians control over repertoire, production, and packaging while emphasizing 20th-century works, including at least one British composition per release.[29] This move reflected Wilson's broader vision for interdisciplinary art that blurred boundaries between post-punk experimentation and classical traditions, drawing on Manchester's rich cultural heritage as home to institutions like the Royal Northern College of Music.[30][31] Factory Classical's roster featured experimental contemporary composers and ensembles, such as Steve Martland, whose debut album Steve Martland (FACD 266, 1989) incorporated rhythmic intensity akin to post-punk energy; and Graham Fitkin, debuting with Flak (FACD 346, 1990), blending acoustic and electronic elements.[32][28] Other key releases included the debut sampler Factory Classical (FACT 226, 1989), featuring the Kreisler String Orchestra performing works by Britten, Shostakovich, and Martland's Drill, alongside recordings by oboist Robin Williams (FACT 236, 1989) and the Duke String Quartet (FACT 246, 1990).[29][33] The label's ties to Factory's rock roots were evident in Metcalfe's involvement, which facilitated orchestral integrations in projects like The Durutti Column's evolving sound, though releases remained firmly rooted in classical forms.[27] The sub-label ultimately released 14 albums before Factory's closure.[34] The sub-label received mixed critical reception upon launch, praised for its bold indie approach to classical music—eschewing stuffy traditions for vibrant, musician-led presentations—but it achieved limited commercial success.[34][13] Tony Wilson highlighted its potential to democratize the genre, noting in a 1989 NME interview that it could pioneer "the pop look" for classical sleeves and attract younger audiences to works by composers like Martland, though the venture ultimately underscored the challenges of diversifying an indie label into niche markets.[30]Financial Decline and Bankruptcy

By the late 1980s, Factory Records faced escalating financial pressures, primarily from the mounting losses at its flagship venue, The Haçienda nightclub. Opened in 1982 as a cultural hub, the club became synonymous with Manchester's rave scene but was plagued by rampant drug use and gang violence, which deterred paying customers and led to operational chaos. By 1991, these issues had resulted in losses exceeding £1 million for the club alone, with total subsidies from New Order reaching between £6 million and £9 million over its lifespan, including £7,000 monthly injections in its final years.[35][36] Poor management of artist advances compounded the strain, particularly with the Happy Mondays, whose recording of their 1992 album Yes Please! in Barbados ballooned from an initial £150,000 budget to over £250,000 due to the band's drug-fueled excesses, including the discovery of crack cocaine, further draining the label's resources.[35][37] Overexpansion exacerbated these problems, as Factory invested heavily in non-core assets during its 1980s peak. The label poured funds into property acquisitions, such as a lavish Ben Kelly-designed building that lost value amid a market crash, and unprofitable ventures like the Dry bar in Manchester's Northern Quarter, which failed to generate sustainable revenue. Efforts to establish international offices in cities like New York and London aimed to support global artist promotion but stretched finances thin without commensurate returns, reflecting a broader pattern of ambitious but undercapitalized growth.[35][12] A pivotal 1990 distribution deal with London Records initially promised stability but soured as Factory's debts mounted, leaving the label unable to meet obligations and leading to a £2 million shortfall by 1992. On November 23, 1992, Factory filed for bankruptcy, with its assets—including the catalogue—sold to London Records for a nominal £1, marking the end of the independent operation. Tony Wilson later reflected on these failures in interviews, admitting the label's idealistic "non-contract" philosophy—where artists retained ownership—proved naive and directly contributed to the collapse, stating, "That document that states 'We own nothing. The musicians own everything' in the end made Factory bankrupt." He also acknowledged broader mismanagement, noting, "You make money, you build a new office, and you go bankrupt."[35][8][12]Post-Closure Developments

2000s and Catalogue Management

Following the bankruptcy of Factory Records in November 1992, London Records acquired the rights to the label's extensive back catalogue, enabling the preservation and re-commercialization of its core artists' recordings.[37] This acquisition laid the groundwork for targeted reissues in the 2000s, focusing on remastered editions and compilations to capitalize on enduring interest in Manchester's post-punk and Madchester scenes. For instance, London Records released the limited-edition In Memory box set in 2007, compiling Joy Division's Unknown Pleasures, Closer, and Still on 180-gram vinyl, limited to 3,000 copies with minimalist artwork evoking the original Factory aesthetic.[38] Similarly, New Order's Singles compilation appeared in 2005, gathering key tracks from their Factory era alongside later material, presented in a two-disc format that highlighted the band's evolution.[39] Legal tensions over master rights emerged in the late 2000s, stemming from ambiguities in Factory's contract-free artist agreements that carried over post-acquisition. Peter Hook, who departed New Order in 2007 amid band fractures, initiated disputes regarding royalties and usage of Joy Division and New Order assets, with early conflicts arising from merchandising and touring promotions that questioned ownership of the Factory-era masters held by London Records.[40] These battles, which escalated into formal lawsuits in the 2010s, originated in the power struggles following Hook's exit and Factory's unresolved legacy issues, complicating catalogue management.[41] The digital era brought further shifts, with Factory's catalogue becoming available on platforms like iTunes starting in the mid-2000s, aligning with the rise of legal downloads following the 2003 launch of the service. Remastered albums, such as Joy Division's 2007 editions, were digitized for online sales, broadening access beyond physical reissues.[42] Streaming availability followed suit by the late 2000s, as labels adapted to services like Spotify, though initial rollouts focused on key titles from Joy Division and New Order to test market demand for Factory's analog-era recordings in a nascent digital landscape. Tony Wilson, despite Factory's closure, continued promoting its legacy through the In The City festival and conference, which he founded in 1992 and ran annually until 2010 in Manchester. This event served as a platform for industry networking and showcases, often featuring retrospectives on Factory artists and the label's cultural influence, sustaining its ethos in the post-bankruptcy era.[43] Complementing these efforts, the 2002 film 24 Hour Party People, directed by Michael Winterbottom, dramatized Factory's history from its punk origins to its 1990s decline, with Steve Coogan portraying Wilson and emphasizing the label's innovative spirit.[44] The movie, released by Pathé and United Artists, reignited public fascination with Factory's story early in the decade.Successor Labels

Following Factory Records' bankruptcy in 1992, its catalogue was acquired by London Records, which later became part of Warner Music before being divested. In 2017, Because Music purchased the majority of the London Records catalogue from Warner Music Group, including key Factory artists such as Happy Mondays and A Certain Ratio, but excluding New Order and Joy Division due to their retention of master rights.[45] This acquisition enabled Because Music to manage and reissue much of the original Factory output under the London Music Stream imprint, focusing on global distribution and digital optimization.[45] Factory Benelux, the original Belgian offshoot of Factory Records established in 1980, was revived in 2012 under the curation of James Nice of LTM Recordings, with the approval of its founders Michel Duval and Annik Honoré. The revived label specializes in reissues of classic Factory Benelux material—such as works by The Durutti Column, Crispy Ambulance, and Section 25—alongside new recordings from legacy acts including The Names and Tuxedomoon.[46] By 2025, Factory Benelux continues to release limited-edition vinyl and digital editions, preserving the imprint's post-punk and experimental ethos through archival remasters and contemporary projects.[46] New Order and the Joy Division estate maintain direct control over their masters, stemming from Factory's unconventional no-contract policy that effectively granted artists ownership of their recordings. This has allowed independent reissues and licensing decisions by the band members and heirs, independent of larger catalogue holders. Complementing these efforts, Haçienda Records, launched in 2022 as the official digital label tied to the FAC51 The Haçienda club, focuses on electronic music continuations with archival club-related releases and new commissions from artists like Robert Owens. As of 2025, ongoing licensing deals through Because Music and artist estates support compilations and streaming availability, ensuring Factory's legacy endures via these successor entities.[45]Artists and Catalogue

List of Recording Artists

Factory Records, operating from 1978 to 1992, amassed a roster exceeding 50 artists, spanning post-punk, electronic, experimental, and classical genres, with signings reflecting Manchester's evolving music scene and occasional forays into world music.[47] The label's artists were diverse, from seminal post-punk bands to Madchester pioneers and avant-garde acts, though it excluded non-contracted performers like Haçienda DJs.[47]Core Post-Punk Acts

These foundational artists, signed primarily in the late 1970s and early 1980s, defined Factory's early sound with raw, influential releases.- Joy Division (signed 1978; notable release: Unknown Pleasures, 1979)[47]

- A Certain Ratio (signed 1978; notable release: The Graveyard and the Ballroom, 1980)[47]

- Section 25 (signed 1980; notable release: Always Now, 1981)[47]

- The Wake (signed 1981; notable release: Harmony, 1982)[47]

- Stockholm Monsters (signed 1981; notable release: Alma Mater, 1984)[47]

- Crispy Ambulance (signed 1979; notable release: The Plateau Phase, 1982)[47]

- The Names (signed 1979; notable release: Swimming, 1982)[47]

- Minny Pops (signed 1980; notable release: Drastic, 1981)[47]

- The Distractions (signed 1978; notable release: You're Smiling, 1978)[47]

- Tiller Boys (signed 1978; notable release: early singles, 1978)[47]

Madchester Era Artists

Emerging in the late 1980s, these acts captured the baggy, rave-influenced Madchester movement, with some loose affiliations.- Happy Mondays (signed 1985; notable release: Squirrel and G-Man Twenty-Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out), 1986)[47]

- Northside (signed 1989; notable release: Chicken Rhythms, 1991)[47]

- James (signed 1986; notable release: Strip-Mine, 1988)[47]

- New Fast Automatic Daffodils (signed 1988; notable release: Pigeonhole, 1990)[47]

Experimental/Electronic Artists

Factory's experimental wing included industrial, synth, and dance acts, signed from 1978 onward, pushing boundaries in electronic music.- New Order (signed 1980; notable release: Movement, 1981)[47]

- Cabaret Voltaire (signed 1978; notable release: Mix-Up, 1979)[47]

- 23 Skidoo (signed 1981; notable release: Just Like Everybody, 1981)[8]

- Quando Quango (signed 1981; notable release: Pigs and Battleships, 1982)[47]

- Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (signed 1978; notable release: Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, 1980)[47]

- 52nd Street (signed 1980; notable release: Children of the Night, 1985)[47]

- Biting Tongues (signed 1979; notable release: In a Rhythm, 1981)[47]

- Kalima (signed 1982; notable release: Nightfall, 1986)[47]

- Electronic (signed 1989; notable release: Getting Away with It, 1990)[47]

- Revenge (signed 1989; notable release: One True Thing, 1990)[47]

- The Other Two (signed 1991; notable release: The Other Two & You, 1991)[47]

- Swamp Children (signed 1980; notable release: early EPs, 1980)[47]

- Royal Family and the Poor (signed 1978; notable release: The Sex of It, 1983)[47]

- Streetlife (signed 1984; notable release: Streetlife, 1985)[47]

- Life (signed 1982; notable release: World in Action, 1983)[47]

- Miaow (signed 1985; notable release: Bring It On Back, 1987)[47]

- Anna Domino (signed 1984; notable release: East and West, 1984)[47]

- The Wendys (signed 1986; notable release: Mambo into Timbuktu, 1987)[47]

- The Adventure Babies (signed 1987; notable release: early singles, 1987)[47]

- The Durutti Column (signed 1978; notable release: Vini Reilly, 1989)[47]

Factory Classical Artists

Through its Factory Classical imprint launched in 1988, the label explored contemporary classical and crossover works.- Gavin Bryars (signed 1988; notable release: The Sinking of the Titanic, 1990 reissue)[8]

- Steve Martland (signed 1988; notable release: Babi Yar, 1988)[47]

- Wim Mertens (signed 1988; notable release: At Home, 1988)[47]

- Rolf Hind (signed late 1980s; notable release: piano works, 1990)[47]

- Duke String Quartet (signed 1989; notable release: contemporary string repertoire, 1990)[47]

- I Fagiolini (signed 1990s transition; notable release: early music crossovers, 1990)[47]

Additional Roster Highlights

The label's broader experimentation included world music and solo ventures, with signings up to the early 1990s.- Fadela (signed 1980s; notable release: You Are My Love, 1985, world music fusion)[47]

- Ludus (signed 1978; notable release: The Visit, 1980)[47]

- John Dowie (signed 1978; notable release: spoken word EP, 1978)[47]

- Martin Hannett (signed as producer/artist, 1978; notable release: The Factory Sample, 1978)[47]

- Thick Pigeon (signed 1983; notable release: Tenebrae, 1984)[47]

- Abecedarians (signed 1985; notable release: Peyote, 1985)[47]

- Marcel King (signed 1984; notable release: Reach, 1984)[47]

- Cath Carroll (signed 1980s; notable release: solo works, 1988)[47]

- ESG (signed for UK release, 1980s; notable release: Come Away with ESG, 1983)[8]

- The Cassandra Complex (signed 1980s; notable release: Theomania, 1988)[8]

- The Chameleons (signed 1983; notable release: Script of the Bridge, 1983)[8]

- Kevin Hewick (signed 1980s; notable release: folk-punk singles, 1980s)[47]

- Nyam Nyam (signed 1980s; notable release: Youth of Today, 1985)[47]

- The Railway Children (signed 1988; notable release: Recurrence, 1988)[47]

- Tuxedomoon (signed 1980s; notable release: collaborations, 1980s)[8]