Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Farnesene

View on Wikipedia | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

α: 3,7,11-trimethyl-1,3,6,10-dodecatetraene

| |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1840984, 1840982, 1840983, 2204279 | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H24 | |

| Molar mass | 204.36 g/mol |

| Density | 0.813 g/mL |

| Boiling point | α-(Z): 125 at 12 mmHg (1.6 kPa) β-(E): 124 °C β-(Z): 95-107 at 3 mmHg (0.40 kPa) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

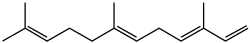

The term farnesene refers to a set of six closely related chemical compounds which all are sesquiterpenes. α-Farnesene and β-farnesene are isomers, differing by the location of one double bond. α-Farnesene is 3,7,11-trimethyl-1,3,6,10-dodecatetraene and β-farnesene is 7,11-dimethyl-3-methylene-1,6,10-dodecatriene. The alpha form can exist as four stereoisomers that differ about the geometry of two of its three internal double bonds (the stereoisomers of the third internal double bond are identical). The beta isomer exists as two stereoisomers about the geometry of its central double bond.

Two of the α-farnesene stereoisomers are reported to occur in nature. (E,E)-α-Farnesene is the most common isomer. It is found in the coating of apples, and other fruits, and it is responsible for the characteristic green apple odour.[1] Its oxidation by air forms compounds that are damaging to the fruit. The oxidation products injure cell membranes which eventually causes cell death in the outermost cell layers of the fruit, resulting in a storage disorder known as scald. (Z,E)-α-Farnesene has been isolated from the oil of perilla. Both isomers are also insect semiochemicals; they act as alarm pheromones in termites[2] or food attractants for the apple tree pest, the codling moth.[3] α-Farnesene is also the chief compound contributing to the scent of gardenia, making up ~65% of the headspace constituents.[4]

β-Farnesene has one naturally occurring isomer. The E isomer is a constituent of various essential oils. It is also released by aphids as an alarm pheremone upon death to warn away other aphids.[5] Several plants, including potato species, have been shown to synthesize this pheromone as a natural insect repellent.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ HUELIN, F.E.; Murray, K.E. (18 June 1966). "α-Farnesene in the Natural Coating of Apples". Nature. 210 (5042): 1260–1261. Bibcode:1966Natur.210.1260H. doi:10.1038/2101260a0. PMID 5967802. S2CID 4287146.

- ^ Šobotník, J.; Hanus, R.; Kalinová, B.; Piskorski, R.; Cvačka, J.; Bourguignon, T.; Roisin, Y. (April 2008), "(E,E)-α-Farnesene, an Alarm Pheromone of the Termite Prorhinotermes canalifrons", Journal of Chemical Ecology, 34 (4): 478–486, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.673.1337, doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9450-2, PMID 18386097, S2CID 8755176

- ^ Hern, A.; Dorn, S. (July 1999), "Sexual dimorphism in the olfactory orientation of adult Cydia pomonella in response to alpha-farnesene", Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 92 (1): 63–72, doi:10.1046/j.1570-7458.1999.00525.x, S2CID 85009862

- ^ Liu, BZ; Gao, Y (September 2000), "Analysis of headspace constituents of Gardenia flower by GC/MS with solid-phase microextraction and dynamic headspace sampling", Chinese Journal of Chromatography, 18 (5): 452–455, PMID 12541711

- ^ Gibson, R. W.; Pickett, J. A. (14 April 1983), "Wild potato repels aphids by release of aphid alarm pheromone", Nature, 302 (5909): 608–609, Bibcode:1983Natur.302..608G, doi:10.1038/302608a0, S2CID 4345998

- ^ Avé, D. A.; Gregory, P.; Tingey, W. M. (July 1987), "Aphid repellent sesquiterpenes in glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii and S. tuberosum", Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 44 (2): 131–138, doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.1987.tb01057.x, S2CID 85582590