Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

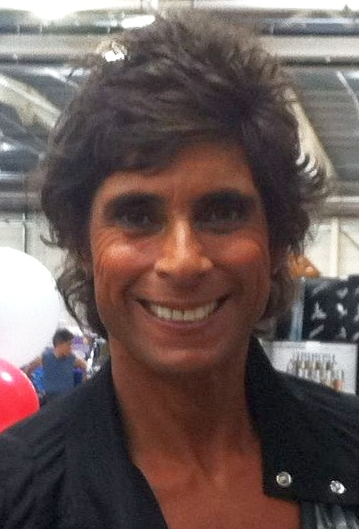

Fatima Whitbread

View on Wikipedia

Fatima Whitbread, MBE (née Vedad; born 3 March 1961) is a British retired javelin thrower. She broke the world record with a throw of 77.44 m (254 ft 3⁄4 in) in the qualifying round of the 1986 European Athletics Championships in Stuttgart, and became the first British athlete to set a world record in a throwing event. Whitbread went on to win the European title that year, and took the gold medal at the 1987 World Championships. She is also a two-time Olympic medallist, winning bronze at the 1984 Summer Olympics and silver at the 1988 Summer Olympics. She won the same medals, respectively, in the Commonwealth Games of 1982 and 1986.

Key Information

After a difficult early childhood, Fatima Vedad was adopted by the family of Margaret Whitbread, a javelin coach. Whitbread won the 1977 English Schools' Athletics Championships intermediate title, and was selected for the 1978 Commonwealth Games, where she finished sixth. The following year, she took gold at the 1979 European Athletics Junior Championships. During her career, she had a well-publicised rivalry with another British javelin athlete, Tessa Sanderson. Whitbread's later career was affected by a long-term shoulder injury, which she believed dated back to her world record throw in 1986. The 1990 UK Athletics Championships was the last event in which she participated, sustaining a further shoulder injury there. In 1992 she formally retired from competition.

She was named the Sports Writers' Association Sportswoman of the Year in 1986 and 1987. She was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 1987 Birthday Honours, for services to athletics. She was voted BBC Sports Personality of the Year in 1987 and received the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Helen Rollason Award in 2023 in recognition of her triumph over the adversity of her childhood, and her continued work on behalf of other children in care environments.

In later years, Whitbread has appeared on several television programmes, including I'm a Celebrity...Get Me Out of Here! in 2011 and 2023, in which she finished in third place both times.

Whitbread was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Roehampton in September 2025.

Early life

[edit]Fatima Vedad was born on 3 March 1961 in Stoke Newington, London,[2][3] to an unmarried Turkish Cypriot mother and Greek Cypriot father.[4] She said "I was abandoned as a baby and left to die in our flat." After being rescued, severely malnourished, "I spent the next 14 years living in institutions, among other traumatised children",[5] occasionally being left in the care of her abusive biological mother.[2] In a 2003 interview with The Observer, she said, "It was a nightmare of a childhood and it was only because I loved sport so much that I got through it and met my true [adoptive] mother."[4]

Some credit for my choice of sport must go to the javelin itself. It is not only a magical event, it is a beautiful one. The flight of the javelin is a glorious sight, and, as I very soon discovered, letting go was a fantastic feeling.

Vedad started throwing the javelin aged 11.[1] According to her account, she had taken up an interest in track and field events after being inspired by the myth of Atalanta, "whom no man could outrun except by cheating, and whose javelin killed a terrible monster"; and by Mary Peters, who won the gold medal at the 1972 Summer Olympics' women's pentathlon.[6]: 96

Vedad met javelin thrower David Ottley at a stadium and asked him if she could use his javelin. He asked her to wait until the coach arrived. The coach was Margaret Whitbread, a physical education teacher at a local school, whom Vedad had previously met when Whitbread refereed a netball match that she played in. After discovering that Vedad stayed at a children's home, Margaret Whitbread passed on some boots and a javelin from a girl who had retired from the event.[2] Three years later, Vedad was adopted by Margaret Whitbread and her family.[4] She spent her teenage years in Chadwell St Mary, Essex, where she attended the Torells School in nearby Grays.[7][8]: 152

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]Whitbread won the English Schools' Athletics Championships intermediate title in 1977,[9] and set a national intermediate record of 158 ft 5 in (48.28 m) in winning the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) women's championship the following month.[10] She placed sixth in the javelin throw at the 1978 Commonwealth Games, throwing 49.16 m (161 ft 3+1⁄4 in).[11] Whitbread won gold in the javelin event at the 1979 European Athletics Junior Championships, throwing 58.20 m (190 ft 11+1⁄4 in).[12] She was selected for the 1980 Summer Olympics event,[1] but, achieving only 49.74 m (163 ft 2+1⁄4 in), she failed to qualify for the final.[13] At the 1982 Commonwealth Games, Whitbread took the bronze medal, throwing 58.86 m (193 ft 1+1⁄4 in), which was 5.6 m (18 ft 4+1⁄4 in) behind champion Sue Howland, from Australia.[11][14]

Having finished behind fellow British competitor Tessa Sanderson in a run of 18 competitions, Whitbread finally defeated her rival with a throw of 62.14 m (203 ft 10+1⁄4 in) to win the UK Athletics Championship in 1983,[15][16] Whitbread won the silver medal at the inaugural World Championships in 1983, having narrowly qualified for the final.[15] She led throughout the final until Tiina Lillak bettered her mark with her last throw of the contest.[1] A few days before the 1984 Summer Olympics, Whitbread had a stomach operation but was still able to travel to the Games and compete.[17] She finished in the bronze medal position, with 67.14 m (220 ft 3+1⁄4 in), and Sanderson (69.56 m (228 ft 2+1⁄2 in)) won gold.[12][15][18] Lillak, who had a stress fracture in her right foot, won the silver medal. After the result, Whitbread commented that "I am so disappointed ... I was not right on the night."[17]

At the 1986 Commonwealth Games in July, Whitbread broke the Games record twice during her first three throws, and led with a distance of 68.54 m (224 ft 10+1⁄4 in), before Sanderson achieved 69.80 m (229 ft 0 in) and won.[19] Whitbread sat down crying on the field after the result for around 30 minutes. After the medal ceremony, she commented, while still visibly upset: "12 years of hard work. Still no [gold] medal ... I've waited two long years since [the 1984 Summer Olympics]. And now I'm humiliated."[20] Sanderson, who had placed behind Whitbread in all of their seven post-1984 Olympics meetings before the Games, said "I don't mind losing to Fatima in the smaller competitions, but not in the big ones."[21]

World record, and European and World championship wins

[edit]The following month, Whitbread broke the javelin world record with a throw of 77.44 m (254 ft 3⁄4 in) in the qualifying round of the 1986 European Championships, more than 2 m further than the record set by Petra Felke of East Germany the previous year. She was the first British athlete to set a world record in a throwing event.[22] Felke led for the first three rounds, before Whitbread produced a throw of 72.68 m (238 ft 5+1⁄4 in) in the fourth round, and 73.68 m (241 ft 8+3⁄4 in) in the fifth round to win her first major championship gold.[23][24] Whitbread later wrote that "All the years of training had finally come to something ... I went on my lap of honour ... Spontaneously, I wiggled my hips in happiness, a victory wiggle."[6]: 168 The record was beaten by Felke in July 1987 with a throw of 79.80 m (261 ft 9+1⁄2 in).[25]

Whitbread qualified for the final of the 1987 World Championships in second place behind Felke.[26] Her throw of 76.64 m (251 ft 5+1⁄4 in) was, at the time, the third-longest ever, and won her the title ahead of Felke. Sanderson was fourth.[27] Her celebratory wiggles after defeating Felke in the World and European event became well known in the UK. She was voted winner of the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award in 1987.[28] David Powell wrote in The Times, that "To that practiced smile, she has added the 'Whitbread wiggle'. She is succeeding in bringing personality to her event in the same way that Willie Banks did to the triple jump."[29]

Later career

[edit]In the months leading up to the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Whitbread suffered from several ailments: a shoulder injury, boils, glandular fever and problems with her gums.[30] Whitbread won the silver medal behind Felke,[15] with a throw that, although her best of the season, was some four metres less than her rival.[1][31] Whitbread commented "If I had to be beaten, I am glad it was by Petra."[31]

Whitbread's later career was affected by a long-term shoulder injury, which she believed dated back to her world record throw in 1986. The 1990 UK Athletics Championships was the last event that she participated in, and she sustained a further shoulder injury there. In 1992 she formally retired from competition.[1][32]

Rivalry with Tessa Sanderson

[edit]Alan Hubbard wrote in a 1990 article in The Observer about Whitbread and Sanderson that "their hate-hate relationship has been one of the most enduring in British sport," lasting almost a decade.[33] In 2009, Tom Lamont commented in The Guardian that "Whitbread and Sanderson were always uneasy rivals and the enmity that developed during their overlapping careers became as famous as their achievements, and seems to survive in their retirement."[34] Hubbard cited Sanderson's perception that Whitbread received preferential treatment from the British Amateur Athletic Board. The Board's promotions officer, Andy Norman, who had a role in setting British athletes' fees, was a family friend of Whitbread and her mother.[35][33] In 1985, Whitbread often participated in international events but Sanderson took part in only one in the season ending in June 1985. Sanderson claimed that this was because she lacked supporters in the meetings where representatives were determined; she said that "Fatima has Andy Norman looking after her in meetings ... and, of course, her mother, Margaret, is the national event coach".[36] In 1987, Sanderson threatened to boycott six official athletics events, for which she was to be paid £1,000 each by British Athletics compared to Whitbread's £10,000.[37][38] Sanderson also objected to the Whitbreads' endorsement of Howland, who competed at the 1990 Commonwealth Games after a two-year doping suspension, since Howland was Australian, and Sanderson felt they should have supported British athletes instead.[33][39]

During their respective careers, Whitbread gained one world and one European title; Sanderson won an Olympic and three Commonwealth golds.[40] In all, Sanderson placed higher in 27 of the 45 times that they faced each other in competition, although Whitbread had the better results of the pair from 1984 to 1987.[41] In 1993, coach Peter Lawler favourably compared Whitbread's technique to Sanderson's, writing in IAAF New Studies in Athletics that "the alignments of Whitbread and [Mick] Hill are as straight as a cricket text book's bat. Whitbread perfected the turning on to the shaft while Sanderson often sagged through the delivery."[42]

Personal life

[edit]Whitbread wrote in her 2012 autobiography that she began a personal relationship with Andy Norman shortly after his divorce in 1986.[8]: 242–244 In 1997, Whitbread married Norman in Copthorne, West Sussex.[43] The couple, who had a son together, divorced in 2006. Norman died of a heart attack in 2007.[44][45]

Whitbread has published two autobiographies written with Adrianne Blue, Fatima: The Autobiography of Fatima Whitbread in 1988, and Survivor: The Shocking and Inspiring Story of a True Champion in 2012.[6][8]

Whitbread is a Christian but, in her own words, "not devout."[46]

Honours and awards

[edit]Whitbread was runner-up to Nigel Mansell in the 1986 BBC Sports Personality of the Year Awards,[47] and won the title the following year.[48] She was named the Sports Writers' Association Sportswoman of the Year in 1986 and 1987.[49][50] She was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 1987 Birthday Honours, for services to athletics.[51][52] Whitbread received the 2023 BBC Sports Personality of the Year Helen Rollason Award, for "outstanding achievement in the face of adversity".[53] She was awarded Freedom of the Borough by the mayor of Thurrock Sue Shinnick and leader of Thurrock Council Lynn Worrall in 2025, alongside her mother Margaret.[54][55]

In September 2025, Whitbread was awarded an honorary doctorate by the university of Roehampton.

In media

[edit]Whitbread has been a guest on television programmes including A Question of Sport (on which she first appeared in 1984),[56] The Little and Large Show (1987 and 1988)[57][58] and The Wright Stuff (2012).[59] In 1989, she was one of the celebrities with experience of fostering or adoption who took part in Find a Family on ITV. The series featured the celebrities' own reflections, and also highlighted specific children, inviting viewers to contact the programme if they were interesting in fostering or adopting them.[60]

In January 1995 Whitbread was interviewed by Andrew Neil, on his one-on-one show Is This Your Life? on Channel 4 which included discussion of Cliff Temple's suicide.[61] Writing in The Guardian, Nancy Banks-Smith described how Whitbread had "stonewalled with stoicism and without sweating" and been unclear in her answers about this. Whitbread also spoke about her unhappiness at how Ben Johnson had been treated after being found doping with steroids.[61] Neil's treatment of Whitbread attracted viewer complaints.[62]

She was a featured "masked celebrity" on Celebrity Wrestling in 2005, and lost her bout against Victoria Silvstedt.[63]

In November 2011, Whitbread took part in the ITV show I'm a Celebrity ... Get Me Out of Here! Whitbread and fellow campmate Antony Cotton left on 2 December 2011, placing her third.[64] One of the challenges on the show involved her wearing a helmet containing about 7,500 cockroaches. The segment was halted after one of the insects crawled up her nose. It was removed by flushing it out through her mouth with water.[65]

In 2012, she was a regular fitness expert appearing on This Morning.[66] Later that year, the stand-alone documentary Fatima Whitbread: Growing Up in Care featured Whitbread's reflections on her own troubled childhood, and her conversations with others who had experienced serious problems from their parent and problems with the UK care system. In The Guardian, David Stubbs wrote "More emotional than forensic, this is compulsory viewing nonetheless."[67][68] In 2020, she trekked the Sultans Trail for BBC Two's Pilgrimage: Road to Istanbul.[69][70]

In 2023, she appeared in I'm a Celebrity... South Africa, placing third again after losing the penultimate trial to camp mates Jordan Banjo and Myleene Klass.[71]

Career statistics

[edit]International competitions

[edit]The table shows Whitbread's performances representing Great Britain and England in international competitions. (q) Indicates overall position in qualifying round.

| Year | Competition | Venue | Position | Distance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Commonwealth Games | Edmonton, Canada | 6th | 49.16 m | [11] |

| 1979 | European Junior Championships | Bydgoszcz, Poland | 1st | 58.20 m | [12] |

| 1980 | Olympic Games | Moscow, Soviet Union | 18th (q) | 49.74 m | [13] |

| 1982 | European Championships | Athens, Greece | 8th | 65.10 m | [12] |

| 1982 | Commonwealth Games | Brisbane, Australia | 3rd | 58.86 m | [11] |

| 1983 | World Championships | Helsinki, Finland | 2nd | 69.14 m | [12] |

| 1984 | Olympic Games | Los Angeles, United States | 3rd | 67.14 m | [12] |

| 1985 | IAAF World Cup | Canberra, Australia | 3rd | 65.12 m | [12] |

| 1986 | Commonwealth Games | Edinburgh, United Kingdom | 2nd | 68.54 m | [11] |

| 1986 | European Championships | Stuttgart, West Germany | 1st | 76.32 m | [12] |

| 1986 | Grand Prix Final | Rome, Italy | 2nd | 69.40 m | [72] |

| 1987 | World Championships | Rome, Italy | 1st | 76.64 m | [12] |

| 1988 | Olympic Games | Seoul, South Korea | 2nd | 70.32 m | [12] |

National titles

[edit]Publications

[edit]- Whitbread, Fatima; Blue, Adrianne (1988). Fatima: The Autobiography of Fatima Whitbread. London: Pelham. ISBN 978-0720718560.

- Whitbread, Fatima; Blue, Adrianne (2012). Survivor: The Shocking and Inspiring Story of a True Champion. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0753540961.

Television and radio

[edit]| Year | Programme | Role | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984, 1986 | A Question of Sport | guest | [56][76][77] |

| 1985 | Cockney Darts Classic | guest | [59] |

| 1987, 1988 | The Little and Large Show | guest | [57][58] |

| 1987 | Wogan | guest | [78] |

| 1989 | Find a Family | participant | [60] |

| 1995 | Is This Your Life? | guest | [61] |

| 2005 | Celebrity Wrestling | masked celebrity | [63] |

| 2009 | Total Wipeout Celebrity Special | contestant | [79] |

| 2011 | I'm a Celebrity ... Get Me Out of Here! | contestant | [64] |

| 2011 | Celebrity Come Dine with Me | participant | [80] |

| 2011 | Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?[a] | contestant | [81] |

| 2012 | This Morning | fitness expert | [66] |

| 2012 | The Wright Stuff | guest | [59] |

| 2012 | Question of Sport | guest | [82] |

| 2012 | Pointless Celebrities | guest | [83] |

| 2012 | Fatima Whitbread: Growing Up in Care | herself | [67] |

| 2015 | Eternal Glory | participant | [84] |

| 2017 | Pointless Celebrities[b] | guest | [85] |

| 2019 | Holiday of My Lifetime | guest | [86] |

| 2019 | Pointless Celebrities[c] | guest | [87] |

| 2020 | Pilgrimage: Road to Istanbul | participant | [69] |

| 2022 | Celebrity SAS: Who Dares Wins | participant | [88] |

| 2023 | I'm a Celebrity... South Africa | participant | [71] |

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Partnered with Russell Watson.

- ^ Sports Personality of the Year edition, partnered with Robin Cousins

- ^ 1980s edition, partnered with Robin Cousins

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Fatima Whitbread". Team GB. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Adie, Kate (2005). "2. What is your mother's name?". Nobody's Child (Digital ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1848943605. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Fatima Whitbread". United Kingdom Athletics. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Jamie (2 March 2003). "Triumph and despair: Fatima Whitbread". The Observer. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012.

- ^ Myers, Hayley (5 October 2024). "Fatima Whitbread: 'I was abandoned as a baby, but I'm one of the lucky ones'". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d Whitbread, Fatima; Blue, Adrianne (1988). Fatima: The Autobiography of Fatima Whitbread. London: Pelham. ISBN 978-0720718560.

- ^ Read, Julian (9 May 2016). "Joe Pasquale: Essex boy at heart". Great British Life. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Whitbread, Fatima; Blue, Adrianne (2012). Survivor: The Shocking and Inspiring Story of a True Champion. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0753540961.

- ^ a b "English schools championship (girls)". Athletics Weekly. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Temple, Cliff (23 August 1977). "A welcome British selection in Clover". The Times. p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e "Fatima Whitbread". The Commonwealth Games Federation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Fatima Whitbread: Honours Summary". World Athletics. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Athletics at the 1980 Moscow Summer Games: Women's Javelin Throw". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Today's medals". Reading Evening Post. 7 October 1982. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Henderson, Jason (2 March 2021). "Fatima Whitbread at 60". Athletics Weekly. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Athletics". Sandwell Evening Mail. 30 May 1983. p. 23.

- ^ a b Mays, Ken (8 August 1984). "How Sanderson buried Moscow miseries". The Daily Telegraph. p. 22.

- ^ "Theresa Sanderson". European Athletics. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Whitbread still bitter". Burton Mail. 1 August 1986. p. 28.

- ^ Keating, Frank (1 August 1986). "Whitbread's bitterness overflows". The Guardian. p. 22.

- ^ "Canadian wins 200 metres". The Daily Oklahoman. 1 August 1986. p. 28.

- ^ Rodda, John (29 August 1986). "Whitbread's world record earns morning glory". The Guardian. p. 20.

- ^ Mays, Ken (30 August 1986). "Whitbread finds her touch for first gold medal". The Daily Telegraph. p. 29.

- ^ "Another golden day". Western Daily Herald. 30 August 1986. p. 28.

- ^ Butcher, Pat (31 July 1987). "Felke throws out a new challenge". The Times. p. 30.

- ^ "Javelin duo lift GB hopes". Cambridge Evening News. 5 September 1987. p. 4.

- ^ Keating, Frank (7 September 1987). "Fatima spearheads British victories". The Guardian. p. 1.

- ^ "Sports Personality of the Year – Past Winners". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 22 July 2004. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ^ Powell, David (10 September 1987). "Whitbread's winter work". The Times. p. 42.

- ^ Mays, Ken (15 August 1988). "Whitbread has happy return". The Daily Telegraph. p. 30.

- ^ a b Mays, Ken (27 September 1988). "Whitbread and Jackson forced to settle for second best". The Daily Telegraph. p. 36.

- ^ Taylor, Louise (14 January 1992). "Javelin stalwart admits defeat". The Times. p. 36.

- ^ a b c Hubbard, Alan (28 October 1990). "Feuds corner: Sanderson v Whitbread". The Observer. p. 23.

- ^ Lamont, Tom (26 July 2009). "Frozen in time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Mays, Ken (1 July 1985). "Whitbread & Sanderson fall out". The Daily Telegraph. p. 22.

- ^ Brasher, Christopher (30 June 1985). "Cram shunted aside by flying Scotsman". The Observer. p. 39.

- ^ "Sport in Brief: Sanderson pay bid – Athletics". The Times. 29 May 1987. p. 42.

- ^ "Athletics: Sanderson offered improved pay deal". The Times. 3 June 1987. p. 54. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Engel, Matthew (2 February 1990). "Coe saves deposit as Sanderson loses her cool". The Guardian. p. 20.

- ^ Field, Pippa (16 August 2019). "Tessa Sanderson on race, rivalry and modelling – Exclusive interview". The Daily Telegraph. pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Tessa Sanderson". UK Athletics. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Lawler, Peter (2016) [1996]. "Javelin: Developments in the Technique". Modern Athlete & Coach. 54 (2): 18–21.

- ^ "Fatima fails in bid to be queen of jungle". East Grinstead Courier and Observer. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Former Olympian Fatima Whitbread: I'd love to dress up and do Strictly Come Dancing". Liverpool Echo. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Rodda, John (28 September 2007). "Andy Norman". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Dunn, Gemma (21 March 2020). "'It just made me realise that faith can in fact bring people together'". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Consolation prize for Nigel". Liverpool Echo. 15 December 1986. p. 30.

- ^ "Whitbread wins trophy". The Daily Telegraph. 14 December 1987. p. 26.

- ^ "Sport in brief: Awards". The Guardian. 14 November 1986. p. 28.

- ^ "Sport in brief: Awards". The Guardian. 11 December 1987. p. 28.

- ^ Sapsted, David (13 June 1987). "Life peerage for former Midlands chief constable". The Times. p. 4.

- ^ "No. 50948". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1987. p. 15.

- ^ "Sports Personality of the Year 2023: Fatima Whitbread wins Helen Rollason Award". BBC Sport. 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Inspirational duo receive borough's ultimate accolade". Thurrock Nub News. 9 August 2025. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Sexton, Christine (19 May 2025). "Quartet of Thurrock heroes honoured with borough freedom". Thurrock Nub News. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b "BBC1". Aberdeen Evening Express. 31 January 1984. p. 2.

- ^ a b "BBC1". Nottingham Evening Post. 21 February 1987. p. 34.

- ^ a b "BBC1". Gloucester News. 3 March 1988. p. 12.

- ^ a b c "Fatima Whitbread". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b Holt, John (11 February 1989). "Star search for a family". Nottingham Evening Post. p. 43.

- ^ a b c Banks-Smith, Nancy (30 January 1995). "Television: Cheap thrill". The Guardian. p. 10.

- ^ "Rocky meeting". The Times. 11 February 1995. p. 16.

- ^ a b Smith, Giles (25 April 2005). "Talent pool that has you wrestling for the remote – Sport on television". The Times. p. 64.

- ^ a b "Cotton and Whitbread voted off Celebrity". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 3 December 2011. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Smith, Giles (29 November 2011). "A question of snort after Whitbread smells danger". The Times. p. 59.

- ^ a b Jefferies, Mark (31 December 2011). "This Morning recruit I'm A Celebrity star Fatima Whitbread to be fat-fighter". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b Stubbs, David (7 August 2012). "TV highlights 08/08/2012: Fatima Whitbread: Growing Up In Care". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Warman, Matt (9 August 2012). "The Daily Telegraph: Painful reality behind the life of a sporting star". The Daily Telegraph. p. 30.

- ^ a b Rajani, Deepika (10 April 2020). "Pilgrimage: The Road to Istanbul line-up: cast, when it's on BBC One tonight and the route they take". i (newspaper). Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Baker, Emily (27 March 2020). "Pilgrimage: Road to Istanbul, BBC2, review: More Duke of Edinburgh than religious education". i (newspaper). Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b "I'm A Celebrity Unveils Line-Up For Upcoming All Stars Series In South Africa". HuffPost UK. 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "IAAF Grand Prix Final". GBR Athletics. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "AAA Junior Championships (women)". Athletics Weekly. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "AAA Championships (women)". Athletics Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "UK Championships". Athletics Weekly. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "BBC1". Aberdeen Press and Journal. 9 January 1986. p. 4.

- ^ "BBC1". Coventry Evening Telegraph. 11 December 1986. p. 24.

- ^ "BBC1". Cambridge Daily News. 9 September 1987. p. 2.

- ^ "BBC – Press Office – Total Wipeout celebrity special press pack: introduction". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Come Dine With Me Athletics Special". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "McFly duo set for Who Wants to Be a Millionaire special". Irish Independent. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Question of Sport". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Pointless Celebrities". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Seale, Jack (6 October 2015). "Tuesday's best TV: Eternal Glory; New Tricks; Alan Johnson: The Post Office and Me; Empire". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Pointless Celebrities". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Holiday of My Lifetime with Len Goodman". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Pointless Celebrities". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Earle, Toby (3 September 2022). "Critic's choice: Celebrity SAS: Who Dares Wins, Channel 4, 9pm". The Times. p. 28.

External links

[edit]- Fatima Whitbread at World Athletics

- Fatima Whitbread at Olympics.com

- Fatima Whitbread at Team GB

- Fatima Whitbread at Olympedia

- Fatima Whitbread at the Commonwealth Games Federation (archived)

- Fatima Whitbread at InterSportStats

- Team GB profile

Fatima Whitbread

View on GrokipediaEarly life

Childhood and family

Fatima Whitbread was born on 3 March 1961 in Stoke Newington, London, to Cypriot parents of Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot descent.[4][5][6] She was abandoned by her biological mother at around three months old, left alone in a council flat in a severely malnourished and ill state, and was rescued by police after a neighbor heard her cries and alerted authorities.[7][8][9] Following her rescue, Whitbread spent several months in hospital recovering before being placed into care around seven months old, where she remained separated from her biological family, including half-siblings, with limited early cultural influences from her Cypriot heritage due to the abandonment.[7][4][9] Whitbread's early years were marked by instability, as she moved through multiple foster homes and children's institutions, including a large Hertfordshire home with around 25 young children, where she lived from around seven months to age five, and later a smaller facility with 14 children.[9][10] These experiences fostered deep emotional challenges, including a persistent sense of abandonment and longing for familial love, yet also built her resilience amid the institutional environment filled with traumatized children. At age 11, she endured a traumatic rape during a visit with her biological mother, adding to the neglect and abuse she faced.[7][8] Key supportive figures during this period included caregivers like "Aunty Rae" and "Aunty Pete," who provided affection and a sense of purpose, helping to mitigate some of the emotional voids.[8][9][10] At age 14, Whitbread found stability when she was adopted by javelin coach Margaret Whitbread and her husband John, who offered her a nurturing home and changed her surname by deed poll to reflect their family.[7][10] Margaret's influence was pivotal, introducing Whitbread to sports as an outlet for her energy and providing the encouragement that shaped her path toward athletics.[7][10] This adoption marked a turning point, transforming the adversities of her foster care years into a foundation of determination.[8]Introduction to athletics

Fatima Whitbread discovered javelin throwing at the age of 11 through school athletics, where her interest in various sports led her to try the event during local competitions.[11] After excelling in a school athletics league and winning a cup, she joined Thurrock Harriers, a club in Essex, where she was introduced to Margaret Whitbread, the club's javelin coach and a former Great Britain thrower.[12] Margaret, who later became her adoptive mother, recognized Whitbread's potential and began coaching her, providing essential equipment like second-hand boots despite the young athlete's limited resources.[13] Whitbread's early training at Thurrock Harriers focused on fundamental techniques, such as grip, approach, and release, under Margaret's guidance in a supportive yet resource-constrained environment typical of local clubs in the 1970s.[14] She demonstrated remarkable dedication, training consistently even as a teenager, which helped build her physical strength and technical proficiency from basic drills onward.[7] At around age 13, Whitbread had her first competitive experiences in junior events, participating in local meets in Essex that allowed her to apply her developing skills against regional peers.[12] Her entry into athletics was deeply motivated by a desire to overcome the instability of her childhood spent in care homes, viewing the sport as an escape and a means to build self-worth through achievement.[7] The stability provided by her adoptive family, including Margaret's role as both coach and parent after formal adoption at age 14, further fueled this drive, transforming javelin into a pathway for personal empowerment.[10]Athletic career

Early competitions and breakthroughs

Whitbread's transition to competitive athletics in the late 1970s marked the beginning of her rise in the sport. At age 18, she achieved her first major international success by winning the gold medal at the 1979 European Athletics Junior Championships in Bydgoszcz, Poland, with a throw of 58.20 m, becoming the first British woman to claim the title in the event.[4] This victory highlighted her potential, following earlier domestic wins such as the 1978 UK junior title and a 53.88 m performance at a national junior meet in Grays.[15] Supported briefly by the stability of her adoption into the Whitbread family, she continued to build momentum through consistent training.[16] Under the guidance of her adoptive mother and coach Margaret Whitbread, a former national javelin thrower, Fatima refined her technique, emphasizing a more fluid crossover run-up and grip adjustments that enhanced her power and accuracy. These improvements propelled her into senior competition, where she captured her first senior national titles at the UK Athletics Championships in 1981 and 1982, solidifying her position as Britain's leading thrower.[4] Her distances progressed notably, reaching 60.14 m in 1980 and climbing to 65.82 m by 1981.[17] Whitbread's senior international breakthrough came in 1982 at the European Athletics Championships in Athens, where she debuted with a 6th-place finish of 65.10 m, demonstrating her competitiveness against elite European athletes. She followed this with a bronze medal at the Commonwealth Games in Brisbane, throwing 58.86 m despite challenging conditions.[4] In 1983, her form peaked with a personal best of 69.54 m at a meet in Grays in July, followed by another best of 69.14 m at the inaugural World Championships in Helsinki, where she earned silver after leading most of the final before Finland's Tiina Lillak's winning throw.[18][19] These results established her as a world-class contender entering the mid-1980s.World record and major championships

At the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, Fatima Whitbread secured the bronze medal in the women's javelin throw with a best distance of 67.14 meters in the final, finishing behind gold medalist Tessa Sanderson of Great Britain and silver medalist Tiina Lillak of Finland.[20] This performance marked Whitbread's breakthrough on the global stage, establishing her as a top contender in the event.[4] Whitbread's career peaked in 1986 at the European Athletics Championships in Stuttgart, where she first set a world record of 77.44 meters during the qualifying round on 28 August, surpassing the previous mark of 75.40 meters held by Petra Felke of East Germany.[21] This throw, the first world record by a British field athlete, was ratified by the International Association of Athletics Federations and immediately elevated the sport's standards, inspiring a new generation of throwers with its unprecedented distance.[22] In the final, Whitbread clinched the gold medal with a throw of 76.32 meters, defending her record-setting form against strong competition from Felke, who took silver with 72.52 meters.[23][24] The following year, at the 1987 World Championships in Rome, Whitbread captured the gold medal with a winning throw of 76.64 meters, becoming the first British woman to win a world title in a throwing event.[25][26] Despite challenging conditions, including extreme heat, her performance underscored her dominance, as she outdistanced silver medalist Felke by over four meters.[7] Whitbread's success stemmed from a technically refined throwing style that emphasized explosive speed and precise form to maximize release velocity, compensating for her relatively shorter stature compared to many rivals.[27] Her approach featured a classical crossover technique with rapid approach steps, a low center of gravity for stability, and a swift shoulder rotation that allowed the javelin to achieve optimal angle and velocity at release, as analyzed in biomechanical studies of elite throwers.[28][29] This method, often described as efficient and without unnecessary flourishes, contributed directly to her record-breaking distances by prioritizing linear momentum and arm extension.[30]Later years and retirement

Whitbread's performance at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul marked a resilient highlight amid mounting physical challenges, where she secured the silver medal with a throw of 70.32 meters despite ongoing shoulder issues and a recent surgical procedure to remove an abscess.[31][32] This achievement, her second Olympic medal, came after a year plagued by multiple injuries including hamstring and heel problems, yet it underscored her determination as she finished just behind East Germany's Petra Felke, who set an Olympic record of 74.68 meters.[31] A chronic shoulder injury, which Whitbread traced back to the strain of her 1986 world record throw, began severely impacting her from 1987 onward, leading to reduced throwing distances and multiple interventions including rotator cuff damage and at least one operation.[4][7] The physical strain culminated in further complications, such as glandular fever and recurring dislocations, forcing her to limit training and competition.[7][32] In a bid to extend her career, Whitbread attempted a comeback during the 1991-1992 season, but persistent shoulder problems prevented her from qualifying for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, leading to her formal retirement announcement on January 13, 1992, at age 30.[4][32] The injuries not only shortened her competitive tenure by an estimated eight years but also exacted a profound emotional toll, including a nervous breakdown in 1988 exacerbated by the stress of her autobiography and unfulfilled ambitions like an Olympic gold.[7][16] Whitbread later described the decision to retire as heartbreaking, likening athletics to her "religion" and mourning the end of a life defined by the sport.[32]Rivalry with Tessa Sanderson

The rivalry between Fatima Whitbread and Tessa Sanderson emerged in the early 1980s as both athletes rose to prominence in British javelin throwing, dominating the event nationally and internationally. Sanderson, who had established herself with Commonwealth golds in 1978 and strong showings at the 1980 and 1984 Olympics, faced increasing competition from Whitbread, who broke through with a silver at the 1983 World Championships. Their competition intensified at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, where Sanderson secured gold with a throw of 69.56 meters—setting an Olympic record—while Whitbread claimed bronze with 67.14 meters, marking the first time two British women medaled in the same Olympic event and drawing immediate media attention to their contrasting paths.[33][34] Key confrontations highlighted the intensity of their head-to-head battles throughout the mid-1980s. At the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Sanderson edged out Whitbread for gold with 69.80 meters to Whitbread's 68.54 meters, reversing Whitbread's recent dominance in direct meetings. However, Whitbread triumphed at the 1986 European Championships in Stuttgart, winning gold with 76.32 meters after setting a world record of 77.44 meters in qualifying, while Sanderson took silver with 72.52 meters. The following year at the World Championships in Rome, Whitbread captured gold with 76.64 meters—a championship record—while Sanderson, hampered by an Achilles injury sustained during the event, finished fourth with 67.54 meters before undergoing surgery on both tendons. These outcomes underscored the rivalry's competitiveness, with Sanderson leading overall in 27 of their 45 meetings.[23][35][34] Media coverage amplified their rivalry, often portraying it as a dramatic clash between Sanderson's raw power-driven style—rooted in her explosive athleticism—and Whitbread's precise, technique-focused approach, which emphasized form and distance optimization. Tensions extended beyond the field, including disputes over national team selection and funding; in 1987, Sanderson threatened to boycott events after learning British Athletics allocated her £1,000 compared to Whitbread's £10,000, citing perceived favoritism by officials like Andy Norman. This bitterness led to minimal communication, with Sanderson later describing the dynamic as "hard and tough" and the media as overly focused on their feud rather than achievements.[33][34] Following the 1988 Seoul Olympics—where Whitbread earned silver with 70.00 meters and Sanderson failed to reach the final due to ongoing injury recovery—the rivalry subsided as both transitioned toward retirement. Sanderson competed until 1996, securing further Commonwealth golds, while Whitbread retired in 1992 after persistent injuries. In later years, mutual respect surfaced; Sanderson expressed regret over their limited friendship during their careers, noting they "could have become better friends," though no full reconciliation occurred by 2024. Their competition ultimately elevated British women's javelin, inspiring future generations.[4][33][34]Personal life

Family and relationships

In 1997, Fatima Whitbread married Andy Norman, a prominent athletics promoter and agent, in Copthorne, West Sussex.[16][36] The couple welcomed their son, Ryan, in February 1998 following successful IVF treatment after years of infertility and a previous miscarriage.[7][37] Whitbread and Norman divorced in 2006 after nearly nine years of marriage, with the separation described as amicable and free of acrimony.[36][38] They maintained a close friendship post-divorce, supporting each other in co-parenting Ryan until Norman's sudden death from a heart attack in 2007 at age 64.[38][36] Whitbread has had limited contact with her biological mother since childhood, with no documented reconciliation in adulthood; instead, her enduring family bonds center on her adoptive mother, Margaret Whitbread, who fostered her at age 14 and provided lifelong support.[16] In August 2025, Fatima and Margaret jointly received the Freedom of the Borough of Thurrock, Essex—the council's highest honor—for their contributions to sport, community, and children's advocacy.[39][40] Today, Whitbread resides in the Essex commuter belt with her son Ryan, now in his mid-20s, and maintains a strong support network rooted in her adoptive family ties.[41][16]Health challenges

Whitbread's athletic career was derailed by a severe shoulder injury sustained during the 1987 World Championships in Rome, where initial damage to her rotator cuff occurred while competing under intense pressure. The injury worsened over the following year, culminating in a complete rupture of the rotator cuff muscle in 1988 as she pushed through pain to maintain her training regimen. This damage proved career-ending, severely limiting her throwing ability and preventing a full recovery despite medical interventions.[42][7] In 1989, Whitbread underwent major shoulder surgery to address the rotator cuff tear, a procedure complicated by the absence of advanced keyhole techniques at the time, which extended her recovery period and wiped out the entire season. A attempted comeback in 1990 resulted in a further fracture to the shoulder, audible to spectators during the UK Championships in Cardiff, necessitating additional medical treatment throughout the 1990s. These multiple surgeries, including interventions in the early 1990s, highlighted the long-term structural damage from repetitive javelin throwing, though full details of each procedure remain tied to her private medical history. The injury's persistence impacted her participation in competitions from 1988 to 1992, ultimately forcing her official retirement at age 31.[43][42][32] Post-retirement, Whitbread has dealt with chronic shoulder complications stemming from the rotator cuff damage, including ongoing pain that affects daily activities such as lifting and reaching. While specific accounts of limited mobility are not extensively documented, the chronic nature of the injury has required sustained management to mitigate its effects on her quality of life. She has incorporated regular physiotherapy sessions and lifestyle adaptations, such as modified strength training, to maintain functionality and prevent further deterioration. Describing herself as a dedicated gym enthusiast even after retiring, Whitbread credits consistent exercise and professional rehabilitation for helping her adapt to the persistent discomfort.[16][11][44] Whitbread has also openly discussed the mental health challenges stemming from her childhood experiences of neglect, abuse, and rape at age 11, which have caused long-term trauma triggers affecting her emotional well-being. She has undergone therapy to address these issues, emphasizing how sport and supportive relationships aided her resilience, and continues to integrate mental health management with her physical recovery efforts.[16][1]Post-athletic career

Media and public appearances

Following her retirement from athletics, Fatima Whitbread transitioned into media roles, leveraging her Olympic achievements to engage audiences through entertainment and broadcasting. In 2011, she participated in the eleventh series of the ITV reality show I'm a Celebrity...Get Me Out of Here!, where she entered the camp on the first day and finished in third place, noted for her fearless approach to Bushtucker Trials, including an infamous incident where a cockroach crawled up her nose during a challenge.[45][46] She returned for the 2023 all-stars spin-off I'm a Celebrity... South Africa, again placing third as a finalist, drawing on her prior experience to mentor fellow contestants.[47] Whitbread has also featured in other television segments, including as a fitness expert on ITV's This Morning with a dedicated segment called "Fatima's Fat Fight," where she promoted health and wellness based on her athletic background.[48] In radio, she appeared on Phoenix FM for interviews in 2024, discussing her career and personal campaigns during shows like Drive in March and Eat My Brunch in November.[49][50] As a sought-after motivational speaker, Whitbread delivers keynote addresses at corporate and public events, focusing on resilience, overcoming adversity, and lessons from her javelin career, such as at the UKISUG Connect 2023 conference where she shared her journey from childhood challenges to world champion.[51][52] Her public engagements emphasize inspirational storytelling, making her a popular choice for talks on personal triumph and determination.[53] In recognition of her inspirational narrative and media presence, Whitbread received the 2023 Helen Rollason Award at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year ceremony, honoring outstanding achievement in the face of adversity.[54]Advocacy and publications

Whitbread has authored several books detailing her athletic achievements and personal experiences. Her first autobiography, Fatima: The Autobiography of Fatima Whitbread, co-written with Adrianne Blue and published in 1988, chronicles her rise to prominence in javelin throwing alongside reflections on her early life challenges. In 2012, she released Survivor: The Shocking and Inspiring Story of a True Champion, also co-authored with Blue, which expands on her career triumphs and the hardships of her childhood in care. More recently, in 2024, Whitbread published the children's book My Bright Shining Star, an illustrated account of her youth in the care system aimed at inspiring young readers facing similar circumstances; she discussed the book's themes in an interview on Phoenix FM.[55][56][50] Following her retirement from competition, Whitbread transitioned into sports marketing, where she managed a highly successful athletics club in the 1990s and 2000s. She led the Chafford Hundred Elite Runners Club, overseeing 34 top athletes including Linford Christie, Dame Kelly Holmes, Steve Cram, and Colin Jackson, and facilitated promotional opportunities that elevated their profiles. This venture established her as a key figure in athlete management and sponsorship within European athletics.[42][57][58] Whitbread is a prominent advocate for foster care reform, drawing from her own experiences growing up in children's homes. As an ambassador for Action for Children, she promotes the importance of stable, loving environments for vulnerable youth and has shared how positive influences in her life shaped her resilience. In a 2024 interview with The Guardian, she highlighted the transformative role of her foster family and sport in overcoming abandonment and institutional care. She intensified her efforts in 2025 by publicly appealing to the UK government to overhaul the care system, criticizing cuts to therapy funding for children in care and calling for better outcomes through policy changes. Through her charity, Fatima's UK Campaign, she continues to push for systemic improvements, including increased support for foster carers and protections for care-experienced individuals. In June 2025, she was appointed the first official ambassador for Brathay Trust, an organization supporting young people through resilience-building programs, further extending her advocacy work.[9][8][59][60][61]Honors and achievements

Athletic awards

During her peak competitive years in the mid-1980s, Fatima Whitbread received several prestigious honors recognizing her dominance in javelin throwing, particularly following her world record and major championship successes. These awards highlighted her contributions to British athletics and her status as one of the sport's elite performers.[1] In 1986, Whitbread finished as runner-up to Formula 1 driver Nigel Mansell in the BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards, a recognition bolstered by her gold medal and world record throw at the European Championships earlier that year.[1] She was also named the Sports Writers' Association Sportswoman of the Year for her outstanding performances, including breaking the women's javelin world record with a throw of 77.44 meters.[62] The following year, 1987, marked an even greater accolades for Whitbread after her victory at the World Championships in Rome, where she secured Britain's only gold medal of the event. She won the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award outright, beating snooker player Steve Davis, who finished second, and golfer Ian Woosnam, who finished third.[63][64][65] Additionally, she received the Sports Writers' Association Sportswoman of the Year honor for the second consecutive year.[62] In the 1987 Birthday Honours, Whitbread was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for services to athletics.[3]Post-retirement recognitions

Following her retirement from competitive athletics in 1992, Fatima Whitbread has received numerous honors recognizing her lifetime achievements in sport and her advocacy efforts for vulnerable youth. In 2012, she was inducted into the England Athletics Hall of Fame, celebrating her pioneering role as the first British woman to break the javelin world record and her Olympic and world championship successes.[12] In December 2023, Whitbread was awarded the Helen Rollason Award at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year ceremony for outstanding achievement in the face of adversity, acknowledging her resilience in overcoming a childhood in care to become a global sporting icon and her subsequent work supporting young people in similar circumstances.[54] On August 8, 2025, Whitbread and her adoptive mother, Margaret Whitbread, were jointly presented with the Freedom of the Borough of Thurrock, the highest civic honor in the area, in recognition of their enduring impact on local sports development and community welfare, including advocacy for children in care.[39][40] In September 2025, during the University of Roehampton's graduation ceremonies, Whitbread received an honorary Doctor of Science for her extraordinary athletic career as an Olympic medallist and world champion, as well as her commitment to social care through initiatives aiding young people facing adversity.[66][67]Career statistics

International results

Fatima Whitbread's international career in the women's javelin throw spanned from 1982 to 1992, marked by consistent medal contention in major competitions and a progression of personal bests that culminated in world record-setting performances. Her debut at the senior level came at the 1982 European Championships, where she established herself as an emerging talent, and she went on to secure multiple medals at the Olympics, World Championships, European Championships, and Commonwealth Games. Key highlights include her breakthrough silver at the 1983 World Championships and her peak in 1986-1987, when she set the world record and won gold medals. The following table summarizes her results in major international competitions, focusing on placements, best distances, and notable achievements such as personal bests (PB) or records.| Year | Event | Location | Placement | Best Distance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | European Championships | Athens, Greece | 8th | 65.10 m | Qualifying throw; early international exposure. |

| 1982 | Commonwealth Games | Brisbane, Australia | 3rd | 58.86 m | Bronze medal; first major international medal. |

| 1983 | World Championships | Helsinki, Finland | 2nd | 69.14 m | PB; first major medal, behind Tiina Lillak's 70.82 m. [68] |

| 1984 | Olympic Games | Los Angeles, USA | 3rd | 67.14 m | Bronze medal; competed with the old javelin design. [69] |

| 1986 | Commonwealth Games | Edinburgh, UK | 2nd | 68.54 m | Silver medal; behind Tessa Sanderson's Games record of 69.80 m. [70] |

| 1986 | European Championships | Stuttgart, West Germany | 1st | 76.32 m | Gold medal; threw world record 77.44 m in qualifiers (PB and WR). [23] |

| 1987 | World Championships | Rome, Italy | 1st | 76.64 m | Gold medal; championship record (PB). [35] |

| 1988 | Olympic Games | Seoul, South Korea | 2nd | 70.32 m | Silver medal; behind Petra Felke's Olympic record of 74.68 m. [31] |