Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Foams are two-phase material systems where a gas is dispersed in a second, non-gaseous material, specifically, in which gas cells are enclosed by a distinct liquid or solid material.[1]: 6 [2]: 4 [3] Foam "may contain more or less liquid [or solid] according to circumstances",[1]: 6 although in the case of gas-liquid foams, the gas occupies most of the volume.[2]: 4

In most foams, the volume of gas is large, with thin films of liquid or solid separating the regions of gas.[4]

Etymology

[edit]The word derives from Old English fām, from Proto-Germanic *faimaz, ultimately related to Sanskrit phéna.

Structure

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

One scale is the bubble: material foams are typically disordered and have a variety of bubble sizes.[5] At larger sizes, the study of idealized foams is closely linked to the mathematical problems of minimal surfaces and three-dimensional tessellations, also called honeycombs.[citation needed] The Weaire–Phelan structure is reported in one primary philosophical source to be the best possible (optimal) unit cell of a perfectly ordered foam,[6][better source needed] while Plateau's laws describe how soap-films form structures in foams.[7]

Foams are examples of dispersed media. In general, gas is present, so it divides into gas bubbles of different sizes (i.e., the material is polydisperse)—separated by liquid regions that may form films, thinner and thinner when the liquid phase drains out of the system films.[8][page needed] When the principal scale is small, i.e., for a very fine foam, this dispersed medium can be considered a type of colloid.[not verified in body]

Formation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Several conditions are needed to produce foam: there must be mechanical work, surface active components (surfactants) that reduce the surface tension, and the formation of foam faster than its breakdown. To create foam, work (W) is needed to increase the surface area (ΔA):

where γ is the surface tension.

One of the ways foam is created is through dispersion, where a large amount of gas is mixed with a liquid. A more specific method of dispersion involves injecting a gas through a hole in a solid into a liquid. If this process is completed very slowly, then one bubble can be emitted from the orifice at a time as shown in the picture below.

One of the theories for determining the separation time is shown below; however, while this theory produces theoretical data that matches the experimental data, detachment due to capillarity is accepted as a better explanation.

The buoyancy force acts to raise the bubble, which is

where is the volume of the bubble, is the acceleration due to gravity, and ρ1 is the density of the gas ρ2 is the density of the liquid. The force working against the buoyancy force is the surface tension force, which is

- ,

where γ is the surface tension, and is the radius of the orifice. As more air is pushed into the bubble, the buoyancy force grows quicker than the surface tension force. Thus, detachment occurs when the buoyancy force is large enough to overcome the surface tension force.

In addition, if the bubble is treated as a sphere with a radius of and the volume is substituted in to the equation above, separation occurs at the moment when

Examining this phenomenon from a capillarity viewpoint for a bubble that is being formed very slowly, it can be assumed that the pressure inside is constant everywhere. The hydrostatic pressure in the liquid is designated by . The change in pressure across the interface from gas to liquid is equal to the capillary pressure; hence,

where R1 and R2 are the radii of curvature and are set as positive. At the stem of the bubble, R3 and R4 are the radii of curvature also treated as positive. Here the hydrostatic pressure in the liquid has to take into account z, the distance from the top to the stem of the bubble. The new hydrostatic pressure at the stem of the bubble is p0(ρ1 − ρ2)z. The hydrostatic pressure balances the capillary pressure, which is shown below:

Finally, the difference in the top and bottom pressure equals the change in hydrostatic pressure:

At the stem of the bubble, the shape of the bubble is nearly cylindrical; consequently, either R3 or R4 is large while the other radius of curvature is small. As the stem of the bubble grows in length, it becomes more unstable as one of the radius grows and the other shrinks. At a certain point, the vertical length of the stem exceeds the circumference of the stem and due to the buoyancy forces the bubble separates and the process repeats.[9]

Stability

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Stabilization

[edit]The stabilization of foam is caused by van der Waals forces between the molecules in the foam, electrical double layers created by dipolar surfactants, and the Marangoni effect, which acts as a restoring force to the lamellae.

The Marangoni effect depends on the liquid that is foaming being impure. Generally, surfactants in the solution decrease the surface tension. The surfactants also clump together on the surface and form a layer as shown below.

For the Marangoni effect to occur, the foam must be indented as shown in the first picture. This indentation increases the local surface area. Surfactants have a larger diffusion time than the bulk of the solution—so the surfactants are less concentrated in the indentation.

Also, surface stretching makes the surface tension of the indented spot greater than the surrounding area. Consequentially—since the diffusion time for the surfactants is large—the Marangoni effect has time to take place. The difference in surface tension creates a gradient, which instigates fluid flow from areas of lower surface tension to areas of higher surface tension. The second picture shows the film at equilibrium after the Marangoni effect has taken place.[10]

Curing a foam solidifies it, making it indefinitely stable at STP.[11]

Destabilization

[edit]Witold Rybczynski and Jacques Hadamard developed an equation to calculate the velocity of bubbles that rise in foam with the assumption that the bubbles are spherical with a radius .

with velocity in units of centimeters per second. ρ1 and ρ2 is the density for a gas and liquid respectively in units of g/cm3 and ῃ1 and ῃ2 is the dynamic viscosity of the gas and liquid respectively in units of g/cm·s and g is the acceleration of gravity in units of cm/s2.

However, since the density and viscosity of a liquid is much greater than the gas, the density and viscosity of the gas can be neglected, which yields the new equation for velocity of bubbles rising as:

However, through experiments it has been shown that a more accurate model for bubbles rising is:

Deviations are due to the Marangoni effect and capillary pressure, which affect the assumption that the bubbles are spherical. For laplace pressure of a curved gas liquid interface, the two principal radii of curvature at a point are R1 and R2.[12] With a curved interface, the pressure in one phase is greater than the pressure in another phase. The capillary pressure Pc is given by the equation of:

- ,

where is the surface tension. The bubble shown below is a gas (phase 1) in a liquid (phase 2) and point A designates the top of the bubble while point B designates the bottom of the bubble.

At the top of the bubble at point A, the pressure in the liquid is assumed to be p0 as well as in the gas. At the bottom of the bubble at point B, the hydrostatic pressure is:

where ρ1 and ρ2 is the density for a gas and liquid respectively. The difference in hydrostatic pressure at the top of the bubble is 0, while the difference in hydrostatic pressure at the bottom of the bubble across the interface is gz(ρ2 − ρ1). Assuming that the radii of curvature at point A are equal and denoted by RA and that the radii of curvature at point B are equal and denoted by RB, then the difference in capillary pressure between point A and point B is:

At equilibrium, the difference in capillary pressure must be balanced by the difference in hydrostatic pressure. Hence,

Since, the density of the gas is less than the density of the liquid the left hand side of the equation is always positive. Therefore, the inverse of RA must be larger than the RB. Meaning that from the top of the bubble to the bottom of the bubble the radius of curvature increases. Therefore, without neglecting gravity the bubbles cannot be spherical. In addition, as z increases, this causes the difference in RA and RB too, which means the bubble deviates more from its shape the larger it grows.[9]

Foam destabilization occurs for several reasons. First, gravitation causes drainage of liquid to the foam base, which Rybczynski and Hadamar include in their theory; however, foam also destabilizes due to osmotic pressure causes drainage from the lamellas to the Plateau borders due to internal concentration differences in the foam, and Laplace pressure causes diffusion of gas from small to large bubbles due to pressure difference. In addition, films can break under disjoining pressure, These effects can lead to rearrangement of the foam structure at scales larger than the bubbles, which may be individual (T1 process) or collective (even of the "avalanche" type).

Mechanical properties

[edit]Liquid foams

[edit]This section needs expansion with: as thorough a treatment as is included in the solid foam subsection. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

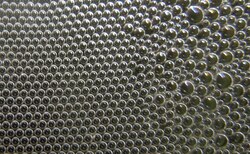

Solid foams

[edit]In closed-cell foam, the gas forms discrete pockets, each completely surrounded by the solid material. In open-cell foam, gas pockets connect to each other. Solid foams, both open-cell and closed-cell, are considered as a sub-class of cellular structures. They often have lower nodal connectivity[jargon] as compared to other cellular structures like honeycombs and truss lattices, and thus, their failure mechanism is dominated by bending of members. Low nodal connectivity and the resulting failure mechanism ultimately lead to their lower mechanical strength and stiffness compared to honeycombs and truss lattices.[13][14]

The strength of foams can be impacted by the density, the material used, and the arrangement of the cellular structure (open vs closed and pore isotropy).[citation needed] To characterize the mechanical properties of foams, compressive stress-strain curves are used to measure their strength and ability to absorb energy since this is an important factor in foam based technologies.[citation needed]

Elastomeric foam

[edit]For elastomeric cellular solids, as the foam is compressed, first it behaves elastically as the cell walls bend, then as the cell walls buckle there is yielding and breakdown of the material until finally the cell walls crush together and the material ruptures.[15] This is seen in a stress-strain curve as a steep linear elastic regime, a linear regime with a shallow slope after yielding (plateau stress), and an exponentially increasing regime. The stiffness of the material can be calculated from the linear elastic regime [16] where the modulus for open celled foams can be defined by the equation:

where is the modulus of the solid component, is the modulus of the honeycomb structure, is a constant having a value close to one, is the density of the honeycomb structure, and is the density of the solid. The elastic modulus for closed cell foams can be described similarly by:

where the only difference is the exponent in the density dependence. However, in real materials, a closed-cell foam has more material at the cell edges which makes it more closely follow the equation for open-cell foams.[17] The ratio of the density of the honeycomb structure compared with the solid structure has a large impact on the modulus of the material. Overall, foam strength increases with density of the cell and stiffness of the matrix material.

Energy of deformation

[edit]Another important property which can be deduced from the stress strain curve is the energy that the foam is able to absorb. The area under the curve (specified to be before rapid densification at the peak stress), represents the energy in the foam in units of energy per unit volume. The maximum energy stored by the foam prior to rupture is described by the equation:[15]

This equation is derived from assuming an idealized foam with engineering approximations from experimental results. Most energy absorption occurs at the plateau stress region after the steep linear elastic regime.[citation needed]

Directional dependence

[edit]The isotropy of the cellular structure and the absorption of fluids can also have an impact on the mechanical properties of a foam. If there is anisotropy present, then the materials response to stress will be directionally dependent, and thus the stress-strain curve, modulus, and energy absorption will vary depending on the direction of applied force.[18] Also, open-cell structures which have connected pores can allow water or other liquids to flow through the structure, which can also affect the rigidity and energy absorption capabilities.[19]

Differences between liquid and solid foams

[edit]Theories regarding foam formation, structure, and properties—in physics and physical chemistry—differ somewhat between liquid and solid foams in that the former are dynamic (e.g., in their being "continuously deformed"), as a result of gas diffusing between cells, liquid draining from the foam into a bulk liquid, etc.[1]: 1–2 Theories regarding liquid foams have as direct analogs theories regarding emulsions,[1]: 3 two-phase material systems in which one liquid is enclosed by another.[20]

Examples

[edit]

- Bath sponge - A bath sponge is an example of an open-cell foam; water easily flows through the entire structure, displacing the air.

- The head on a glass of beer

- Soap foam[21] (also known as suds)

- Sleeping mat - A sleeping mat is an example of a product composed of closed-cell foam.

Foam can also refer to something that is analogous to foam, such as quantum foam.

Applications

[edit]

Liquid foams

[edit]Liquid foams can be used in fire retardant foam, such as those that are used in extinguishing fires, especially oil fires.[citation needed]

The dough of leavened bread has traditionally been understood as a closed-cell foam—yeast causing bread to rise via tiny bubbles of gas that become the bread pores—where the cells do not connect with each other. Cutting the dough releases the gas in the bubbles that are cut, but the gas in the rest of the dough cannot escape.[citation needed] When dough is allowed to rise too far, it becomes an open-cell foam, in which the gas pockets are connected; cutting the dough surface at that point would cause a large volume of gas to escape, and the dough to collapse.[citation needed][22] Recent research has indicated that the pore structure in bread is 99% interconnected into one large vacuole, thus the closed-cell foam of the moist dough is transformed into an open cell solid foam in the bread.[23][non-primary source needed]

The unique property of gas-liquid foams having very high specific surface area is exploited in the chemical processes of froth flotation and foam fractionation.[citation needed]

Solid foams

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Solid foams are a class of lightweight cellular engineering materials. These foams are typically classified into two types based on their pore structure: open-cell-structured foams (also known as reticulated foams) and closed-cell foams. At high enough cell resolutions, any type can be treated as continuous or "continuum" materials and are referred to as cellular solids,[24] with predictable mechanical properties.

Open-cell foams can be used to filter air. For example, a foam embedded with catalyst has been shown to catalytically convert formaldehyde to benign substances when formaldehyde polluted air passes through the open cell structure.[25]

Open-cell-structured foams contain pores that are connected to each other and form an interconnected network that is relatively soft. Open-cell foams fill with whatever gas surrounds them. If filled with air, a relatively good insulator results, but, if the open cells fill with water, insulation properties would be reduced. Recent studies have put the focus on studying the properties of open-cell foams as an insulator material. Wheat gluten/TEOS bio-foams have been produced, showing similar insulator properties as for those foams obtained from oil-based resources.[26] Foam rubber is a type of open-cell foam.

Closed-cell foams do not have interconnected pores. The closed-cell foams normally have higher compressive strength due to their structures. However, closed-cell foams are also, in general more dense, require more material, and as a consequence are more expensive to produce. The closed cells can be filled with a specialized gas to provide improved insulation. The closed-cell structure foams have higher dimensional stability, low moisture absorption coefficients, and higher strength compared to open-cell-structured foams. All types of foam are widely used as core material in sandwich-structured composite materials.

The earliest known engineering use of cellular solids is with wood, which in its dry form is a closed-cell foam composed of lignin, cellulose, and air. From the early 20th century, various types of specially manufactured solid foams came into use. The low density of these foams makes them excellent as thermal insulators and flotation devices and their lightness and compressibility make them ideal as packing materials and stuffings.

An example of the use of azodicarbonamide[27] as a blowing agent is found in the manufacture of vinyl (PVC) and EVA-PE foams, where it plays a role in the formation of air bubbles by breaking down into gas at high temperature.[28][29][30]

The random or "stochastic" geometry of these foams makes them good for energy absorption, as well. In the late 20th century to early 21st century, new manufacturing techniques have allowed for geometry that results in excellent strength and stiffness per weight. These new materials are typically referred to as engineered cellular solids.[24]

Syntactic foam

[edit]Integral skin foam

[edit]Integral skin foam, also known as self-skin foam, is a type of foam with a high-density skin and a low-density core. It can be formed in an open-mold process or a closed-mold process. In the open-mold process, two reactive components are mixed and poured into an open mold. The mold is then closed and the mixture is allowed to expand and cure. Examples of items produced using this process include arm rests, baby seats, shoe soles, and mattresses. The closed-mold process, more commonly known as reaction injection molding (RIM), injects the mixed components into a closed mold under high pressures.[31]

Gallery

[edit]-

Micrograph of temper (memory) foam

-

Industrial CT scanning of a foam ball [clarification needed]

-

Polystyrene foam cushioning

Foam scales and properties

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Weaire, D.L.; Hutzler, Stefan (1999). The Physics of Foams. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198510977. Retrieved August 30, 2024. Note, this source focuses only on liquid foams.

- ^ a b Cantat, I; Cohen-Addad, S; Elias, F; Graner, F; Höhler, R; Pitois, O; Rouyer, F & Saint-Jalmes, A (2013). Foams: Structure and Dynamics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199662890. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Note, this source also focuses on liquid foams. - ^ The general use of the term, which includes both noun and verb forms, is both narrower and broader than the one from material science described here. In general use, it is narrower, in that it most often refers to liquid foams; it is broader in that it includes all manners of such, and the actions to produce them, hence, according to Merriam-Webster, the term refers to "a light frothy mass of fine bubbles formed in or on the surface of a liquid or from a liquid", giving the examples of those produced by "salivating or sweating", ones stably produced to fight fires, ones that are the product of gas bubbles introduced during manufacturing, and then the further broad examples of sea foam, and then anything resembling the foregoing. Finally, the general definition includes actions to produce all of the above. See "Foam". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014.

- ^ "Foam Explained". Accushape Die Cutting. Retrieved June 13, 2025.

- ^ "Particle-stabilized foams", Bubble and Foam Chemistry, Cambridge University Press, pp. 269–306, July 31, 2016, doi:10.1017/cbo9781316106938.009, ISBN 978-1-107-09057-6, retrieved May 24, 2025

- ^ Morgan, F. (2008). "Existence of Least-perimeter Partitions". Philosophical Magazine Letters. 88 (9–10): 647–650. arXiv:0711.4228. Bibcode:2008PMagL..88..647M. doi:10.1080/09500830801992849.

- ^ Ball, Philip (January 18, 2008). "The maths behind group showers". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2007.352. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Lucassen, J. (1981). Lucassen-Reijnders, E. H. (ed.). Anionic Surfactants – Physical Chemistry of Surfactant Action. NY, USA: Marcel Dekker.[page needed]

- ^ a b Bikerman, J.J. "Formation and Structure" in Foams New York, Springer-Verlag, 1973. ch 2. sec 24–25

- ^ "The Foam" (PDF). IHC News. January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Stevenson, Paul (January 3, 2012). Foam Engineering: Fundamentals and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119961093.

- ^ Wilson, A.J, "Principles of Foam Formation and Stability." Foams: Physics, Chemistry, and Structure. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1989, ch 1

- ^ Queheillalt, Douglas T.; Wadley, Haydn N.G. (January 2005). "Cellular metal lattices with hollow trusses". Acta Materialia. 53 (2): 303–313. Bibcode:2005AcMat..53..303Q. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2004.09.024.

- ^ Kooistra, Gregory W.; Deshpande, Vikram S.; Wadley, Haydn N.G. (August 2004). "Compressive behavior of age hardenable tetrahedral lattice truss structures made from aluminium". Acta Materialia. 52 (14): 4229–4237. Bibcode:2004AcMat..52.4229K. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2004.05.039. S2CID 13958881.

- ^ a b Courtney, Thomas H. (2005). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Waveland Press, Inc. pp. 686–713. ISBN 1-57766-425-6.

- ^ M. Liu et al. Multiscale modeling of effective elastic properties of fluid-filled porous materials International Journal of Solids and Structures (2019) 162, 36-44

- ^ Ashby, M. F. (1983). "The Mechanical Properties of Cellular Solids". Metallurgical Transactions. 14A (9): 1755–1769. Bibcode:1983MTA....14.1755A. doi:10.1007/bf02645546. S2CID 135765088.

- ^ Li, Pei; Guo, Y. B.; Shim, V. P. W. (2020). "A rate-sensitive constitutive model for anisotropic cellular materials - Application to a transversely isotropic polyurethane foam". International Journal of Solids and Structures. 206: 43–58. doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2020.08.007. S2CID 225310568 – via Elsevier.

- ^ Yu, Y. J.; Hearon, K.; Wilson, T. S.; Maitland, D. J. (2011). "The effect of moisture absorption on thephysical properties of polyurethane shapememory polymer foams". Smart Materials and Structures. 20 (8). Bibcode:2011SMaS...20h5010Y. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/20/8/085010. PMC 3176498. PMID 21949469.

- ^ IUPAC (1997). "Emulsion". Compendium of Chemical Terminology (The "Gold Book"). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02065. ISBN 978-0-9678550-9-7. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012.

- ^ Crystal (August 14, 2023). "The Science Behind Natural Soaps' Bubbles". The Freckled Farm Soap Company. Retrieved May 31, 2025.

- ^ The open structure of an over-risen dough is easy to observe: instead of consisting of discrete gas bubbles, the dough consists of a gas space filled with threads of the flour-water paste.[original research?][citation needed]

- ^ Wang, Shuo; Austin, Peter; Chakrabati-Bell, Sumana (2011). "It's a maze: The pore structure of bread crumbs". Journal of Cereal Science. 54 (2): 203–210. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2011.05.004.

- ^ a b Gibson, Ashby (1999). Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316025420.

- ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Kirschman, David L. (January 23, 2023). "Catalytic Surgical Smoke Filtration Unit Reduces Formaldehyde Levels in a Simulated Operating Room Environment". ACS Chemical Health & Safety. 30 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1021/acs.chas.2c00071. ISSN 1871-5532. S2CID 255047115.

- ^ Wu, Qiong; Andersson, Richard L.; Holgate, Tim; Johansson, Eva; Gedde, Ulf W.; Olsson, Richard T.; Hedenqvist, Mikael S. (2014). "Highly porous flame-retardant and sustainable biofoams based on wheat gluten and in situ polymerized silica". Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2 (48). 20996–21009. doi:10.1039/C4TA04787G.

- ^ Reyes-Labarta, J.A.; Marcilla, A. (2008). "Kinetic Study of the Decompositions Involved in the Thermal Degradation of Commercial Azodicarbonamide". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 107 (1): 339–346. doi:10.1002/app.26922. hdl:10045/24682.

- ^ Reyes-Labarta, J.A.; Marcilla, A. (2012). "Thermal Treatment and Degradation of Crosslinked Ethylene Vinyl Acetate-Polyethylene-Azodicarbonamide-ZnO Foams. Complete Kinetic Modelling and Analysis". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 51 (28): 9515–9530. doi:10.1021/ie3006935.

- ^ Reyes-Labarta, J.A.; Marcilla, A. (2008). "Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis of the Thermal Treatment of Ternary Mixtures of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate, Polyethylene and Azodicarbonamide". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 110 (5): 3217–3224. doi:10.1002/app.28802. hdl:10045/13312.

- ^ Reyes-Labarta, J.A.; Olaya, M.M.; Marcilla, A. (2006). "DSC Study of the Transitions Involved in the Thermal Treatment of Foamable Mixtures of PE and EVA Copolymer with Azodicarbonamide". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 102 (3): 2015–2025. doi:10.1002/app.23969. hdl:10045/24680.

- ^ Ashida, Kaneyoshi (2006). Polyurethane and related foams: chemistry and technology. CRC Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-1-58716-159-9. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Weaire, D.L.; Hutzler, Stefan (1999). The Physics of Foams. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198510977. Retrieved August 30, 2024. A modern treatise almost exclusively focused on liquid foams.

- Gibson, Lorna J.; Ashby, Michael F. (1997). Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties. Cambridge Solid State Science. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521499119. Retrieved August 30, 2024. A treatise termed a classic by Weaire & Hutzler (1999), on solid foams, and the reason they limit their focus to liquid foams.

- Cantat, I; Cohen-Addad, S; Elias, F; Graner, F; Höhler, R; Pitois, O; Rouyer, F; Saint-Jalmes, A (2013). Foams: Structure and Dynamics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199662890. Retrieved August 30, 2024. Note, this source also focuses on liquid foams.

- Thomas Hipke, Günther Lange, René Poss: Taschenbuch für Aluminiumschäume. Aluminium-Verlag, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-87017-285-5.

- Hannelore Dittmar-Ilgen: Metalle lernen schwimmen. In: Dies.: Wie der Kork-Krümel ans Weinglas kommt. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-7776-1440-3, S. 74.

External links

[edit]- Andrew M. Kraynik, Douglas A. Reinelt, Frank van Swol Structure of random monodisperse foam

- Moriarty, Philip (2010). "Foam Physics". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

.jpg/250px-The_top_of_foamy_drink_(Unsplash).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-The_top_of_foamy_drink_(Unsplash).jpg)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {W_{max}}{E_{s}}}=0.05\left({\frac {\rho ^{*}}{\rho _{s}}}\right)^{2}\left[0.975-1.4\left({\frac {\rho ^{*}}{\rho _{s}}}\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/037551eb3a9f7c6a5595941b2b2336f792664d2f)

![Silicone foam penetration seal [clarification needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/Silikonschaum_riesenblase_verfuellungsversuch.jpg/120px-Silikonschaum_riesenblase_verfuellungsversuch.jpg)

![Industrial CT scanning of a foam ball [clarification needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Foam_ball.png/120px-Foam_ball.png)

![Foamed aluminum [clarification needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/Aluminium_foam.jpg/120px-Aluminium_foam.jpg)