Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

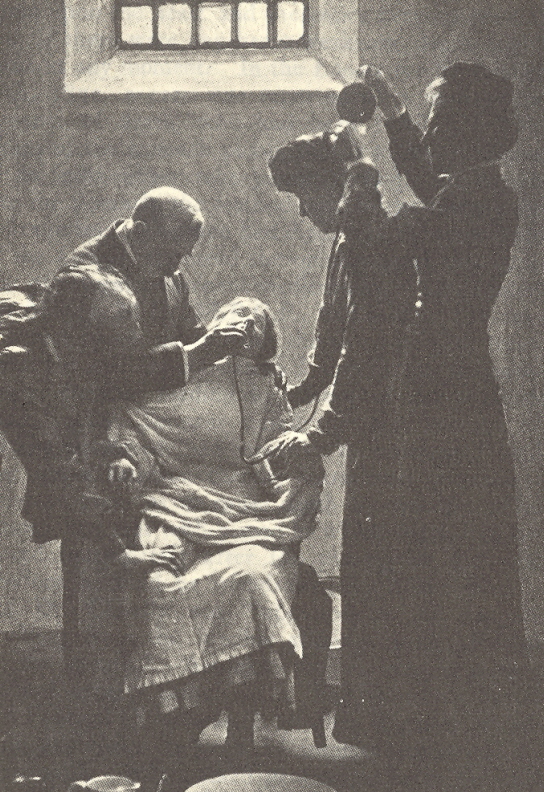

Force-feeding

View on Wikipedia

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term gavage (UK: /ˈɡævɑːʒ, ɡæˈvɑːʒ/,[2][3] US: /ɡəˈvɑːʒ/,[3][4] French: [ɡavaʒ] ⓘ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose (nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into the stomach.

Of humans

[edit]In psychiatric settings

[edit]Within some countries,[which?] in extreme cases, patients with anorexia nervosa who continually refuse significant dietary intake and weight restoration interventions may be involuntarily fed by force via nasogastric tube under restraint within specialist psychiatric hospitals.[5] Such a practice may be highly distressing for both anorexia patients and healthcare staff.[5]

In prisons

[edit]Some countries force-feed prisoners when they go on hunger strike. It has been prohibited since 1975 by the Declaration of Tokyo of the World Medical Association, provided that the prisoner is "capable of forming an unimpaired and rational judgment." The violation of this prohibition may be carried out in a manner that can be categorised as torture, as it may be extremely painful and result in severe bleeding and spreading of various diseases via the exchanged blood and mucus, especially when conducted with dirty equipment on a prison population.[6]

Canada

[edit]The Canadian government accepts the Declaration of Tokyo as made by the World Medical Association, and does not carry out the force-feeding of inmates against their will who reject any nourishment, however the Correction Service of Canada has stated that they reserve the right to do so since they have a legal obligation to maintain the health of individuals in their care. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act of 1992 directly prohibits the force feeding of inmates in Canada.[7][8][9]

United Kingdom

[edit]

Suffragettes who had been imprisoned while campaigning for votes for women went on hunger strike and were force fed. This lasted until the Prisoners Act of 1913, also known as the Cat and Mouse Act, whereby debilitated prisoners would be released, allowed to recover, and then re-arrested. Rubber tubes were inserted through the mouth (only occasionally through the nose) and into the stomach, and food poured down; the suffragettes were held down by force while the instruments were inserted into their bodies, which has been likened to rape.[10] In a smuggled letter, Sylvia Pankhurst described how the warders held her down and forced her mouth open with a steel gag. Her gums bled, and she vomited most of the liquid.[11]

Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women's Social and Political Union, was horrified by the screams of women being force-fed in HM Prison Holloway. She wrote: "Holloway became a place of horror and torment. Sickening scenes of violence took place almost every hour of the day, as the doctors went from cell to cell performing their hideous office. ... I shall never while I live forget the suffering I experienced during the days when those cries were ringing in my ears." When prison officials tried to enter her cell, Pankhurst, in order to avoid being force-fed, raised a clay jug over her head and announced: "If any of you dares so much as to take one step inside this cell, I shall defend myself."[12]

In 1911, Wiliam Ball, a male working class supporter who had broken two windows and consequently been sentenced to two months, was given this treatment and then separated from contact with his family, leading to his clandestine transfer to a mental hospital. This case was taken up by groups such as WSPU and the Men's League for Women's Suffrage, whose pamphlet on the case had the subtitle Official Brutality on the increase.[13]

The first woman in Scotland to be force fed was Ethel Moorhead, in Calton Jail, who despite being under medical supervision became seriously ill.[14] The governor, Major William Stewart, argued that her illness was not caused by the feeding regime, but also said:

We must face the fact that artificial feeding is attended with risk and we must teach [suffragette prisoners] that, while we appreciate the risks, we are quite prepared to go on and will not be deterred from detaining people like [Moorhead] because there is a risk to their health, if we take the necessary steps to make sure their detention is effective... They have the idea that they can frighten us by pointing out the risk to health.[15]

But the governor also recognised that there was a risk of the public deciding that prison authorities were "going too far".[15] After Moorhead's release, the WPSU published a handbill, Scotland Disgraced and Dishonoured, with Moorhead describing her experience being fed by force:

The tube filled up all my breathing space, I couldn't breathe. The young man began pouring in the liquid food.

I heard the noises I was making of choking and suffocation – uncouth noises human beings are not intended to make and which might be made by a vivisected dog. Still he kept on pouring.[16]

In 1914, Frances Parker, another Scottish suffragette, was being force-fed by the rectum (a nutrient enema, a standard procedure before the invention of intravenous therapy) and once by the vagina[15] in the Perth prison:

Thursday morning, 16th July ... the three wardresses appeared again. One of them said that if I did not resist, she would send the others away and do what she had come to do as gently and as decently as possible. I consented. This was another attempt to feed me by the rectum, and was done in a cruel way, causing me great pain. She returned some time later and said she had "something else" to do. I took it to be another attempt to feed me in the same way, but it proved to be a grosser and more indecent outrage, which could have been done for no other purpose than torture. It was followed by soreness, which lasted for several days.[17]

Djuna Barnes, an American journalist, agreed to submit to force-feeding for a 1914 New York World magazine article. Barnes wrote, "If I, play acting, felt my being burning with revolt at this brutal usurpation of my own functions, how they who actually suffered the ordeal in its acutest horror must have flamed at the violation of the sanctuaries of their spirits." She concluded, "I had shared the greatest experience of the bravest of my sex."[18]

British prison authorities force-fed Irish republican prisoners during the Irish revolutionary period and the Troubles. In 1917, Irish Republican Brotherhood leader Thomas Ashe died as a result of complications from force-feeding while incarcerated at Dublin's Mountjoy Jail. In 1973 four Irish Republican prisoners were force fed over a 200-day period. Gerry Kelly, Hugh Feeney, Dolours Price and Marian Price were force-fed while on hunger strike in separate British prisons.[19] In 1974, Provisional Irish Republican Army members Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg were force-fed while on hunger strike. Gaughan was subjected to 17 force-feedings during a hunger strike in HM Prison Wakefield. The force-feeding procedure was described: "Six to eight guards would restrain the prisoner and drag him or her by the hair to the top of the bed, where they would stretch the prisoner’s neck over the metal rail, force a block between his or her teeth and then pass a feeding tube, which extended down the throat, through a hole in the block." In 1974, Stagg was force-fed for 68 days and survived but died on another hunger strike in 1976.[20]

United States

[edit]Ethel Byrne was the first female political prisoner in the United States to be subjected to force feeding[21] after she was jailed at Blackwell Island workhouse on January 22, 1917, for her activism in advocating for the legalization of birth control. She subsequently went on a hunger strike and refused to drink water for 185 hours.[22]

Under United States jurisdiction, force-feeding is frequently used in the U.S. military prison in Guantanamo Bay, prompting in March 2006 an open letter by 250 doctors in The Lancet, warning that the participation of any doctor is contrary to the rules of the World Medical Association.[23][24][25]

In the 2009 case Lantz v. Coleman,[26] the Connecticut Superior Court authorized the state Department of Correction to force-feed a competent prisoner who had refused to eat voluntarily.[27] In 2009, terrorist Richard Reid, known as the "shoe bomber," was force-fed while on a hunger strike at the United States Penitentiary, Florence ADX, the federal supermax prison in Colorado.[28] Hundreds of force-feedings have been reported at ADX Florence.[29]

Forced feeding has also been used by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement against detained asylum seekers on hunger strike.[30] In February 2019, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed that such treatment of detainees could constitute a breach of the United Nations Convention against Torture.[30] The Associated Press quoted one 22-year old asylum seeker who alleged that "he was dragged from his cell three times a day and strapped down on a bed as a group of people poured liquid into tubes inserted into his nose."[30]

Soviet Union

[edit]Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky described how he was force-fed:

The feeding pipe was thick, thicker than my nostril, and would not go in. Blood came gushing out of my nose and tears down my cheeks, but they kept pushing until the cartilages cracked. I guess I would have screamed if I could, but I could not with the pipe in my throat. I could breathe neither in nor out at first; I wheezed like a drowning man — my lungs felt ready to burst. The doctor also seemed ready to burst into tears, but she kept shoving the pipe farther and farther down. Only when it reached my stomach could I resume breathing, carefully. Then she poured some slop through a funnel into the pipe that would choke me if it came back up. They held me down for another half-hour so that the liquid was absorbed by my stomach and could not be vomited back, and then began to pull the pipe out bit by bit.[31]

"The unfortunate patients had their mouth clamped shut, had a rubber tube inserted into their mouth or nostril. They keep on pressing it down until it reaches your esophagus. A funnel is attached to the other end of the tube and a cabbage-like mixture poured down the tube and through to the stomach. This was an unhealthy practice, as the food might have gone into their lungs and caused pneumonia."[32]

United Nations War Crimes Tribunal

[edit]On December 6, 2006, the United Nations War Crimes Tribunal at The Hague approved the use of force-feeding of Serbian politician Vojislav Šešelj. They decided it was not "torture, inhuman or degrading treatment if there is a medical necessity to do so... and if the manner in which the detainee is force-fed is not inhuman or degrading."[33]

Israel

[edit]In 2015, the Knesset passed a law allowing the force-feeding of prisoners in response to a hunger strike by a Palestinian detainee who had been held for months in administrative detention. Israeli doctors refused to feed Mohammad Allan against his will, and he resumed eating after the Supreme Court temporarily released him.[34]

Greece

[edit]Forced feeding has been ordered by Greek courts against hunger strikes at different times including in 2021 when a Greek prosecutor proposed the force-feeding of Dimitris Koufontinas in the effort of stopping Koufontinas's 65 day hunger and water strike which started in February 2021. The doctors of the hospital of Lamia, where Koufodinas was hospitalised refused to administer force feeding procedures,[35][36] a Greek doctors' union has called the practice torture.[37] A similar situation played out in 2014 when 21 year old convicted anarchist bank robber and childhood friend of Alexandros Grigoropoulos, Nikos Romanos who engaged in a hunger-strike for access to education which lead to a force-feeding being ordered.[38] Romanos successfully resisted the force-feeding order with the help of his doctors.[39] Romanos terminated his hunger-thirst strike after 30 days having won access to a university education.[40][41]

Other forms

[edit]Force-feeding of pernicious substances may be used as a form of torture and/or physical punishment. While in prison in northern Bosnia in 1996, some Serbian prisoners have described being forced to eat paper and soap.[42]

Sometimes it has been alleged that prisoners are forced to eat foods forbidden by their religion. The Washington Post has reported that Muslim prisoners in Abu Ghraib prison under the U.S.-led coalition described in sworn statements having been forced to eat pork and drink alcohol, both of which are strictly forbidden in Islam (see Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse).[43]

Of babies

[edit]

According to Infant feeding by artificial means: a scientific and practical treatise on the dietetics of infancy[44], a French system of feeding newborn or premature babies who could not suckle was known as gavage. Sadler dates its origin to 1874 and quotes Étienne Stéphane Tarnier, a pioneer perinatologist, describing the procedure. [45] Nowadays, infants in a neonatal intensive care unit are likely to be fed by nasogastric or sometimes orogastric tubes.[46]

For girls before marriage

[edit]Force-feeding used to be practiced in North Africa and still is in Mauritania. Fatness was considered a marriage asset in women; culturally, voluptuous figures were perceived as indicators of wealth. In this tradition, some girls are forced by their mothers or grandmothers to overeat, often accompanied by physical punishment (e.g., pressing a finger between two pieces of wood) should the girl not eat. The intended result is a rapid onset of obesity, and the practice may start at a young age and continue for years. This is still the tradition in the rather undernourished Sahel country Mauritania (where it is called leblouh), where it induces major health risks in the female population; some younger men no longer insist on voluptuous brides, but traditional beauty norms remain part of the culture.[47]

In slavery

[edit]Some Africans on the Middle Passage journey to slavery in the United States tried to take their own lives by starving themselves, and were force fed with a contraption called the speculum orum. This device forced the slave's mouth open in order to be fed.[48]

Of domestic animals

[edit]Force-feeding has been used to prepare animals for slaughter. In some cases, such as is the case with ducks and geese raised for foie gras and peking duck, it is still practiced today.

In farming

[edit]

Force-feeding is also known as gavage, from the verbal noun form of the French verb gaver meaning "to gorge". This term specifically refers to force-feeding of ducks or geese in order to fatten their livers in the production of foie gras.

Force-feeding of birds is practiced mostly on geese or male Moulard ducks, a Muscovy/Pekin hybrid. Preparation for gavage usually begins four to five months before slaughter. For geese, after an initial free-range period and treatment to assist in esophagus dilation (eating grass, for example), the force-feeding commences. Gavage is performed two to four times a day for two to five weeks, depending on the size of the fowl, using a funnel attached to a slim metal or plastic feeding tube inserted into the bird's throat to deposit the food into the bird's crop (the storage area in the esophagus). A grain mash, usually maize mixed with fats and vitamin supplements, is the feed of choice. Waterfowl are suited to the tube method due to a non-existent gag reflex and an extremely flexible esophagus, unlike other fowl such as chickens. These migratory waterfowl are also said to be ideal for gavage because of their natural ability to gain large amounts of weight in short periods of time before cold seasons.

In modern Egypt, the practice of fattening geese and male Muscovy ducks by force-feeding them various grains is present, unrelated to foie gras production, but for general consumption. This is done by hand rather than by tube, as is European force-feeding. However, this practice is not widespread on commercial farms, and is done mostly by individuals. The term used for this is tazġīṭ (تزغيط), from the verb zaġġaṭ(a) (زغّط).

Shen Dzu is a similar practice of force-feeding pigs.

In scientific research

[edit]Gavage is used in some scientific studies such as those involving the rate of metabolism. It is practiced upon various laboratory animals, such as mice. Liquids such as medicines may be administered to the animals via a tube or syringe.[49]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pankhurst, Sylvia (1911). The Suffragette. New York: Sturgis & Walton Company. p. 433.

- ^ "gavage". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ a b "Gavage". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ "gavage". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ a b Kodua, Michael; Mackenzie, Jay-Marie; Smyth, Nina (2020). "Nursing assistants' experiences of administering manual restraint for compulsory nasogastric feeding of young persons with anorexia nervosa". International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 29 (6): 1181–1191. doi:10.1111/inm.12758. ISSN 1447-0349. PMID 32578949. S2CID 220046454.

- ^ BBC News: "UN concern at Guantanamo feeding."

- ^ O'Hara, Jane (November 7, 1983). "Force feeding to end a fast". Maclean's. Canada: St. Joseph Communications. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Hunger Strike: Managing an Inmate's Health". Correctional Service Canada. Government of Canada. 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

As prolonged engagement in a hunger strike may cause serious personal injury/harm and/or death, Do Not Resuscitate Orders and directions regarding care within Advance Directives do not apply. For any inmate who loses capacity to make a conscious choice, or becomes unconscious, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) staff will intervene to preserve life.

- ^ Branch, Legislative Services (2024-10-10). "Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Corrections and Conditional Release Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2025-08-26.

- ^ Purvis, June; Emmeline Pankhurst, London: Routledge, p 134, ISBN 0-415-23978-8

- ^ Pugh, Martin; The Pankhursts, UK: Penguin Books, 2001, p 259, ISBN 0-14-029038-9

- ^ Pankhurst, Emmeline (1914). My Own Story. London: Virago Limited (1979). pp. 251 & 252. ISBN 978-0-86068-057-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Museum of London | Free museum in London". collections.museumoflondon.org.uk. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- ^ "Force Feeding Purvis Moorhead". www.johndclare.net. May 2009. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ^ a b c Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 471, 505. ISBN 978-1-4088-4404-5. OCLC 1016848621.

- ^ Bird, Jackie (2009-10-09). "Scottish suffragettes braved hunger strikers, prison and violence to win vote". dailyrecord. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ^ "Force-feeding extracts from Purvis". www.johndclare.net. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ^ Mills, Eleanor; with Kira Cochrane (eds.) (2005). Journalistas: 100 Years of the Best Writing and Reporting by Women Journalists. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1667-3. p 163–166.

- ^ Miller, Ian (2024). "Hunger Strikers and Force-Feeding during the Troubles". Epidemic Belfast. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ O'Hara, T (20 February 2004). "Michael Gaughan (1950-1974)". Irelands Own. the Hunger Strike Commemoration Committee. Archived from the original on 2007-02-11. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ Lepore, Jill (2014). The Secret Life of Wonder Woman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-385-35404-2.

- ^ "About Sanger". Margaret Sanger Papers Project. MSPP. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Doctors attack U.S. over Guantanamo". BBC News. 2006-03-10. Archived from the original on 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2006-03-15.

The letter, in the medical journal The Lancet, said doctors who used restraints and force-feeding should be punished by their professional bodies.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (2005-12-30). "46 Guantanamo detainees join hunger strike". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2010-03-14. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ "Gitmo Hunger Strikers' Numbers Grow". The New Standard. 2005-12-30. Archived from the original on 2010-03-14. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ Lantz v. Coleman, 978 A. 2d 164 (Conn. Super. Ct. 2009)

- ^ Appel, Jacob M. Beyond Guantanamo: Torture Thrives in Connecticut November 17, 2009

- ^ "'Shoe bomber' is on hunger strike". BBC News. June 11, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ "Supermax: A Clean Version Of Hell". CBS News. October 14, 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ a b c "UN: US force-feeding immigrants may breach torture agreement". Associated Press. 2019-02-08. Retrieved 2019-02-08.

- ^ Daily Kos: "The WaPo prints a torture story."

- ^ "Guidelines for Physicians Concerning Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in Relation to Detention and Imprisonment". wma.net. World Medical Association. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (December 7, 2006). "War crimes tribunal orders force-feeding of Serbian warlord". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ^ "Hunger Strike Raises Debate About Force-Feeding In Israeli Prisons". 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Convicted Terrorist Koufontinas Ends Hunger Strike". GreekReporter.com. 2021-03-14. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ "Greek Prosecutor Calls for Force-Feeding of Convicted Terrorist Koufontinas". 24 February 2021.

- ^ Presse, AFP-Agence France. "Greek Hitman On Hunger Strike Suffers Kidney Failure". www.barrons.com. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ Megaloudi, Fragkiska. "Greece hunger-striker". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ "As protests mount, Athens braces for the worst". The World from PRX. 30 July 2016. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Jailed Greek anarchist calls off hunger strike". news.yahoo.com. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ "Victory for the hunger strike of Nikos Romanos". libcom.org. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- ^ Banks, Lynne Reid (30 March 1996). "Serb prisoners 'forced to eat soap' during months of beatings in solitary confinement". The Independent. London.

- ^ "New Details of Prison Abuse Emerge". The Washington Post. 2004-05-21.

- ^ Sadler, S H (1896). Infant feeding by artificial means: a scientific and practical treatise on the dietetics of infancy (2nd ed.). London. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sadler, S H (1896). (2nd ed.).

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Enteral Feeding of the Neonate". www.starship.org.nz. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Women rethink a big size that is beautiful but brutal" Clare Soares 11 July 2006. Christian Science Monitor

- ^ "Africans in America/Part 1/The Middle Passage". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Ley, Ruth E.; Mahowald, Michael A.; Magrini, Vincent; Mardis, Elaine R.; Gordon, Jeffrey I. (2006). "An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest". Nature. 444 (7122): 1027–1031. Bibcode:2006Natur.444.1027T. doi:10.1038/nature05414. PMID 17183312. S2CID 4400297.

- BBC 1 TV programme "Force-fed" November 2, 2005

External links

[edit] Works related to How It Feels to Be Forcibly Fed at Wikisource

Works related to How It Feels to Be Forcibly Fed at Wikisource- Voluntary and Voluntary Total Fasting and Refeeding, Detention Hospital, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba

- Manifesto for the abolition of force-feeding

Force-feeding

View on GrokipediaForce-feeding is the practice of delivering nutrition to individuals or animals that refuse voluntary intake, typically through invasive techniques such as nasogastric tubes or oral intubation, distinguishing it from consensual artificial feeding by its coercive nature.[1]

Employed primarily in correctional settings to avert fatalities among hunger-striking detainees, it compels medical intervention against self-imposed starvation, often involving physical restraint and risking complications like esophageal perforation or aspiration pneumonia.[1][2]

In agriculture, force-feeding ducks and geese via repeated esophageal tubing induces hepatic steatosis for foie gras production over 12-15 days, yielding enlarged livers but prompting welfare critiques over documented injuries including trauma and inflammation.[3][4]

Historically prominent in the early 20th-century British suffragette campaigns, where imprisoned protesters rejecting food were tube-fed, the method fueled public outrage and propaganda depicting it as state-sanctioned violence, amplifying demands for political prisoner status.[5]

Ethically contentious, force-feeding pits preservation of life against bodily autonomy, with organizations like the World Medical Association condemning physician participation in penal contexts as unethical, while some legal frameworks permit it to counter self-harm absent consent revocation capacity.[6][7][8]