Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

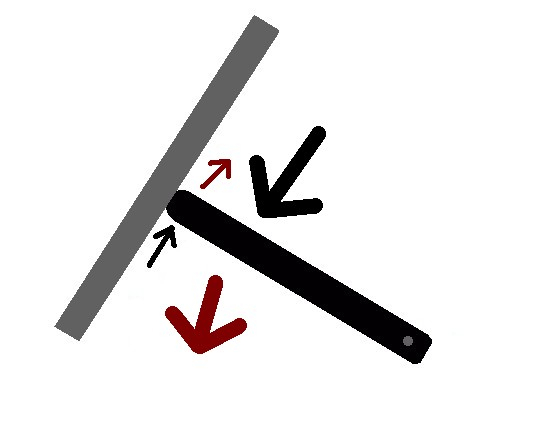

Friction torque

View on Wikipedia

In mechanics, friction torque is the torque caused by the frictional force working in couple that occurs when two objects in contact move.[1] Like all torques, it is a rotational force that may be measured in newton meters or pounds-feet.

Engineering

[edit]Friction torque can be disruptive in engineering. There are a variety of measures engineers may choose to take to eliminate these disruptions. Ball bearings are an example of an attempt to minimize the friction torque.[2]

Friction torque can also be an asset in engineering. Bolts and nuts, or screws are often designed to be fastened with a given amount of torque, where the friction is adequate during use or operation for the bolt, nut, or screw to remain safely fastened. This is true with such applications as lug nuts retaining wheels to vehicles, or equipment subjected to vibration with sufficiently well-attached bolts, nuts, or screws to prevent the vibration from shaking them loose.[3]

Examples

[edit]- When a cyclist applies the brake to the forward wheel, the bicycle tips forward due to the frictional torque between the wheel and the ground.[4]

- When a golf ball hits the ground it begins to spin in part because of the friction torque applied to the golf ball from the friction between the golf ball and the ground.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ Fischer, Alfons; Bobzin, Kirsten (2011-02-10). Friction, Wear and Wear Protection. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-62852-0.

- ^ Bloch, Heinz P. (1992-01-01), Lobanoff, Val S.; Ross, Robert R. (eds.), "Rolling Element Bearings and Lubrication*", Centrifugal Pumps (Second Edition), Boston: Gulf Professional Publishing, pp. 524–555, ISBN 978-0-08-050085-0, retrieved 2024-12-02

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ "How to Prevent Vibrational Loosening". provenproductivity.com. 2019-04-05. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ Allen, John (2024-12-02). "Understanding torque as it applies to bicycles". sheldonbrown.com. Retrieved 2024-02-12.

- ^ Normani, Franco. "Physics Of Golf". Real World Physics Problems. Retrieved 2024-12-02.