Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

G-flat major

View on Wikipedia| Relative key | E-flat minor |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | G-flat minor →enharmonic: F-sharp minor |

| Dominant key | D-flat major |

| Subdominant key | C-flat major |

| Enharmonic key | F-sharp major |

| Component pitches | |

| G♭, A♭, B♭, C♭, D♭, E♭, F | |

G-flat major is a major scale based on G♭, consisting of the pitches G♭, A♭, B♭, C♭, D♭, E♭, and F. Its key signature has six flats.

Its relative minor is E-flat minor (or enharmonically D-sharp minor). Its parallel minor, G-flat minor, is usually replaced by F-sharp minor, since G-flat minor's two double-flats make it generally impractical to use. Its enharmonic equivalent, F-sharp major, contains six sharps.

The G-flat major scale is:

Changes needed for the melodic and harmonic versions of the scale are written in with accidentals as necessary. The G-flat harmonic major and melodic major scales are:

Scale degree chords

[edit]The scale degree chords of G-flat major are:

- Tonic – G-flat major

- Supertonic – A-flat minor

- Mediant – B-flat minor

- Subdominant – C-flat major

- Dominant – D-flat major

- Submediant – E-flat minor

- Leading-tone – F diminished

Characteristics

[edit]Like F-sharp major, G-flat major is rarely chosen as the main key for orchestral works. It is more often used as a main key for piano works, such as the impromptus of Chopin and Schubert. It is the predominant key of Maurice Ravel's Introduction and Allegro for harp, flute, clarinet and string quartet, and is also used in the second movement "Le Gibet" of Ravel's famous Gaspard de la nuit.

A striking use of G-flat major can be found in the love duet "Tu l'as dit" that concludes the fourth act of Giacomo Meyerbeer's opera Les Huguenots.[citation needed]

When writing works in all 24 major and minor keys, Alkan, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Shchedrin and Winding used G-flat major over F-sharp major. Muzio Clementi chose F-sharp in his set for the prelude, but G-flat for the final "Grande Exercice" which modulates through all the keys.

Antonín Dvořák composed Humoresque No. 7 in G-flat major, while its middle section is in the parallel key (F-sharp minor, enharmonic equivalent to the theoretical G-flat minor).

Gustav Mahler was fond of using G-flat major in key passages of his symphonies. Examples include: the choral entry during the finale of his Second Symphony,[1] during the first movement of his Third Symphony,[2] the modulatory section of the Adagietto from his Fifth Symphony,[3] and during the Rondo–Finale of his Seventh Symphony.[4] Mahler's Tenth Symphony was composed in the enharmonic key of F-sharp major.

This key is more often found in piano music, as the use of all five black keys allows an easier conformity to the player's hands, despite the numerous flats. In particular, the black keys G♭, A♭, B♭, D♭, and E♭ correspond to the 5 notes of the G-flat pentatonic scale. Austrian composer Franz Schubert chose this key for his third impromptu from his first collection of impromptus (1827). Polish composer Frédéric Chopin wrote two études in the key of G-flat major: Étude Op. 10, No. 5 "Black Key" and Étude Op. 25, No. 9 "Butterfly" as well as a waltz in Op. 70. French composer Claude Debussy used this key for one of his most popular compositions, La fille aux cheveux de lin, the eighth prélude from his Préludes, Book I (1909–1910). The Flohwalzer can be played in G-flat major, or F-sharp major, for its easy fingering.

John Rutter has chosen G-flat major for a number of his compositions, including "Mary's Lullaby" and "What sweeter music".[5] In a charity interview[6] he explained several of the reasons that drew him to this key. In many soprano voices there is a break round about E (a tenth above middle C) with the result that it is not their best note, bypassed in the key of G-flat major. It is thus, he claims, a very vocal key. Additionally, writing for strings, there are no open strings in this key, so that vibrato can be used on any note, making it a warm and expressive key. He also cites its facility on a piano keyboard.

References

[edit]- ^ Mahler, Gustav. Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 in Full Score, Dover, ISBN 0-486-25473-9 (1987) p. 354.

- ^ Mahler, Gustav. Symphonies Nos. 3 and 4 in Full Score, Dover, ISBN 0-486-26166-2 (1989), p. 53.

- ^ Mahler, Gustav. Symphonies Nos. 5 and 6 in Full Score, Dover, ISBN 0-486-26888-8 (1991), p. 175.

- ^ Mahler, Gustav. Symphony No. 7 in Full Score, Dover, ISBN 0-486-27339-3 (1992), p. 223.

- ^ Rutter, John (2005). John Rutter Carols. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780193533813.

- ^ "'Confessions of a Carol Composer': John Rutter in conversation with Anna Lapwood. (video time index 35:16)". YouTube. 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2023-12-06.

External links

[edit]- https://www.academia.edu › 49275551 › G_Flat_Major_Repertoire

G-flat major

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Key Signature

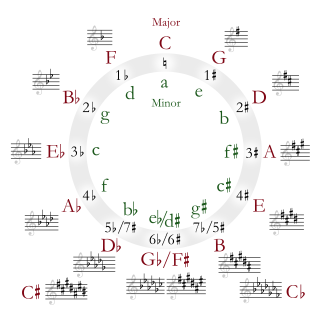

The key signature of G-flat major consists of six flats: B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, and C♭.[7] These accidentals are added in a fixed order derived from the circle of fifths, progressing counterclockwise from the key of F major: first B♭ for F major, then E♭ for B♭ major, A♭ for E♭ major, D♭ for A♭ major, G♭ for D♭ major, and finally C♭ for G-flat major.[1] This sequential addition ensures that each new flat lowers the fifth scale degree of the previous key, maintaining diatonic consistency across related tonalities.[8] In notation, the key signature is positioned immediately to the right of the clef at the beginning of the staff, with the flat symbols aligned vertically in their specific locations corresponding to the notes they alter. In the treble clef, B♭ appears on the middle line, E♭ in the space immediately above, A♭ on the line above that, D♭ in the subsequent space, G♭ on the next line, and C♭ in the space above.[9] In the bass clef, the flats are placed on: B♭ on the second line from the bottom, E♭ in the third space from the bottom, A♭ on the top line, D♭ on the third line from the bottom, G♭ on the bottom line, and C♭ in the second space from the bottom.[10] This placement adheres to standard conventions established in Western music notation, with each flat positioned on the line or space of the note it affects. Unlike sharp-based keys, the G-flat major signature contains no sharps, relying entirely on flats to define its tonal center, which visually clusters the accidentals toward the upper portion of the staff in both clefs.[1] This flat-exclusive notation contrasts with enharmonically equivalent keys that employ sharps, highlighting the systematic duality in key representation. G-flat major is enharmonically equivalent to F-sharp major. Historically, the six-flat signature is preferred over the six-sharp alternative for F-sharp major in contexts like orchestral writing for transposing instruments in flat keys (e.g., clarinets in B♭), where it reduces ledger lines and accidentals during modulations to nearby flat tonalities, a practice rooted in 19th-century orchestration conventions.[11]Scale Construction

The G-flat major scale is constructed by starting on the root note G♭ and following the standard major scale interval pattern of whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step (W-W-H-W-W-W-H), where a whole step spans two half steps and a half step spans one half step on the chromatic scale.[12][13] This pattern ensures the scale's characteristic major tonality, defined by the specific placement of half steps between the third and fourth degrees and between the seventh and eighth degrees, creating a bright and resolved sound distinct from minor scales.[14] The ascending natural G-flat major scale consists of the following pitches, corresponding to its scale degrees:- 1 (tonic): G♭

- 2 (supertonic): A♭

- 3 (mediant): B♭

- 4 (subdominant): C♭

- 5 (dominant): D♭

- 6 (submediant): E♭

- 7 (leading tone): F

- 8 (octave): G♭[15][13]

Harmonic Structure

Diatonic Chords

The diatonic chords in G-flat major are the triads constructed by stacking thirds on each degree of the G-flat major scale, which consists of the notes G♭, A♭, B♭, C♭, D♭, E♭, and F.[16] These chords form the foundational harmonic vocabulary of the key, following the standard pattern for major keys: major triads on the tonic (I), subdominant (IV), and dominant (V) degrees; minor triads on the supertonic (ii), mediant (iii), and submediant (vi) degrees; and a diminished triad on the leading tone (vii°).[17] This results in three major chords, three minor chords, and one diminished chord.[16] The following table enumerates the diatonic triads, including their Roman numeral notation, chord quality, and constituent notes (root, third, fifth):| Roman Numeral | Chord Quality | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | Major | G♭–B♭–D♭ |

| ii | Minor | A♭–C♭–E♭ |

| iii | Minor | B♭–D♭–F |

| IV | Major | C♭–E♭–G♭ |

| V | Major | D♭–F–A♭ |

| vi | Minor | E♭–G♭–B♭ |

| vii° | Diminished | F–A♭–C♭ |