Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Geminal

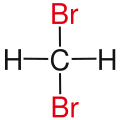

View on WikipediaIn chemistry, the descriptor geminal (from Latin gemini 'twins'[1]) refers to the relationship between two atoms or functional groups that are attached to the same atom. A geminal diol, for example, is a diol (a molecule that has two alcohol functional groups) attached to the same carbon atom, as in methanediol. Also the shortened prefix gem may be applied to a chemical name to denote this relationship, as in a gem-dibromide for "geminal dibromide".[citation needed]

The concept is important in many branches of chemistry, including synthesis and spectroscopy, because functional groups attached to the same atom often behave differently from when they are separated. Geminal diols, for example, are easily converted to ketones or aldehydes with loss of water.[2]

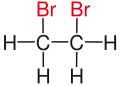

| Alkane | geminal | vicinal | isolated | |

| Methane |

|

|

not existing | not existing |

| Ethane |

|

|

|

not existing |

| Propane |

|

|

|

|

| Substituents on selected dibromoalkanes labeled red. | ||||

The related term vicinal refers to the relationship between two functional groups that are attached to adjacent atoms. This relative arrangement of two functional groups can also be described by the descriptors α and β.

1H NMR spectroscopy

[edit]In 1H NMR spectroscopy, the coupling of two hydrogen atoms on the same carbon atom is called a geminal coupling. It occurs only when two hydrogen atoms on a methylene group differ stereochemically from each other. The geminal coupling constant is referred to as 2J since the hydrogen atoms couple through two bonds. Depending on the other substituents, the geminal coupling constant takes values between −23 and +42 Hz.[3][4]

Synthesis

[edit]The following example shows the conversion of a cyclohexyl methyl ketone to a gem-dichloride through a reaction with phosphorus pentachloride. This gem-dichloride can then be used to synthesize an alkyne.

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of GEMINI". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Peter Taylor (2002), Mechanism and synthesis, Book 10 of Molecular world. Open University, Royal Society of Chemistry; ISBN 0-85404-695-X. 368 pages

- ^ H. Günther: NMR-Spektroskopie; Grundlagen,Konzepte und Anwendungen der Protonen- und Kohlenstoff-13-Kernresonanzspektroskopie in der Chemie. 3. neubearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 1992, S. 103.

- ^ D. H. Williams, I. Fleming: Strukturaufklärung in der organischen Chemie; Eine Einführung in die spektroskopischen Methoden. 6. überarbeitete Auflage, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 1991, S. 109.

Geminal

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Definition

In chemistry, the term geminal refers to the relationship between two atoms, functional groups, or substituents that are attached to the same central atom in a molecule.[7][8] This positioning distinguishes geminal arrangements from vicinal ones, where substituents are on adjacent atoms./Alkyl_Halides/Reactivity_of_Alkyl_Halides/Alkyl_Halide_Reactions/Reactions_of_Dihalides) The general structural formula for a geminal system is , where and represent the geminal substituents (which may be identical or different) and denotes hydrogen or other groups bonded to the central carbon./Alkyl_Halides/Properties_of_Alkyl_Halides/Geminal_Dihalide) This configuration often influences molecular reactivity and stability, as the proximity of the substituents on a single atom can lead to unique electronic and steric effects. The term geminal originates from the Latin word geminus, meaning "twin," reflecting the paired nature of the substituents on the same atom; it was first recorded in English usage around 1967.[1] A classic example is dichloromethane (), where two chlorine atoms are geminally attached to the carbon, forming a simple geminal dihalide./Alkyl_Halides/Properties_of_Alkyl_Halides/Geminal_Dihalide)Related Terms

In organic chemistry, the term "geminal" describes two substituents or functional groups attached to the same atom of a parent structure, often denoted by the prefix "gem-" in common nomenclature, such as gem-dichloride for compounds of the general formula R₂CCl₂.[9][8] While the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) primarily employs numerical locants for precise positioning (e.g., 1,1-dichloroethane), the "gem-" prefix remains widely used in descriptive contexts to highlight the adjacency on a single atom, facilitating clear communication in structural discussions.[10] Geminal positioning contrasts with vicinal, where substituents occupy adjacent atoms, and with 1,3-diaxial interactions in stereochemistry, which involve non-bonded steric repulsions between axial substituents on the same side of a cyclohexane ring but separated by two carbons.[8][11] To illustrate these positional relationships in simple alkanes, consider propane (C₃H₈) with hypothetical substituents X (e.g., halogens):| Positional Descriptor | Example Structure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Geminal | CH₃-CH₂-CHX₂ | Both X groups on the same carbon (C3). |

| Vicinal | CH₃-CHX-CH₂X | X groups on adjacent carbons (C2 and C3). |

| 1,3-Diaxial (stereochemical, in cyclic analogs) | N/A (acyclic example; applies to chair cyclohexane with axial groups at C1 and C3) | Steric interaction between substituents two carbons apart in axial positions. |

Types of Geminal Compounds

Geminal Dihalides

Geminal dihalides are organic compounds featuring two halogen atoms attached to the same carbon atom, with the general formula R₂CX₂, where R is typically hydrogen or an alkyl group and X denotes a halogen such as chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), or iodine (I).[14] These compounds are commonly encountered with smaller halogens like Cl and Br, as larger halogens such as I introduce greater steric demands that can influence reactivity patterns in synthetic applications.[15] Prominent examples include dichloromethane (CH₂Cl₂) and chloroform (CHCl₃). Dichloromethane is a volatile, colorless liquid with a boiling point of 39.6 °C, a density of 1.33 g/cm³ at 20 °C, and significant polarity (dielectric constant of 8.93), making it miscible with many organic solvents and moderately soluble in water (13 g/L at 20 °C).[16] Chloroform, similarly colorless and volatile, exhibits a higher boiling point of 61.2 °C and density of 1.49 g/cm³ at 20 °C, with a lower dielectric constant of 4.81 due to its more symmetric structure, yet it remains polar and widely soluble in organic media (8 g/L in water at 20 °C).[17] These physical properties—low boiling points and polarity—render them effective as extractants and reaction media in laboratory and industrial settings. The reactivity of geminal dihalides stems from the strong electron-withdrawing inductive effect of the halogen atoms, which activates the central carbon toward nucleophilic attack, often facilitating substitution or elimination pathways.[18] For example, the geminal chlorines in CH₂Cl₂ and CHCl₃ enhance electrophilicity, enabling reactions with nucleophiles like hydroxide or alkoxides to form substitution products, though steric factors around the carbon can modulate rates compared to monohalides.[19] In organic synthesis, they serve as versatile reagents, such as in the generation of dihalocarbenes under basic conditions, and as solvents that stabilize polar transition states without participating in hydrogen bonding.[20] Industrially, geminal dihalides like dichloromethane and chloroform are produced on a massive scale, with global dichloromethane output reaching approximately 1.68 million metric tons in 2024, primarily via chlorination of methane or chloromethane.[21] Chloroform production, estimated at approximately 757,000 metric tons in 2024, is predominantly directed toward the synthesis of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), such as HCFC-22 (chlorodifluoromethane), via fluorination with hydrogen fluoride.[22] These HCFCs function as refrigerants and foam-blowing agents, though phase-out efforts under the Montreal Protocol are reducing reliance on such precursors due to ozone depletion concerns.[23] Overall, geminal dihalides underpin key processes in chemical manufacturing, from solvent applications to fluorocarbon production.Geminal Diols

Geminal diols possess the general structure , featuring two hydroxyl groups bonded to the same carbon atom, and typically arise as the hydrated forms of aldehydes or ketones in equilibrium with their carbonyl tautomers, quantified by the hydration constant .[24] The stability of these diols is influenced by substituent effects, with electron-withdrawing groups adjacent to the geminal carbon favoring the diol form by increasing the electrophilicity of the carbonyl carbon in the parent compound. For instance, in chloral hydrate (), the trichloromethyl group exerts a strong inductive withdrawal, rendering the diol highly stable and isolable as a colorless crystalline solid.[25][26] Equilibrium constants highlight these differences: formaldehyde exhibits , resulting in nearly complete hydration in water, while acetone shows , with the carbonyl form overwhelmingly favored.[27] Chloral hydrate exemplifies a practically significant geminal diol, employed historically as a sedative and hypnotic since the 1870s to manage insomnia, anxiety, and procedural sedation in pediatrics, though its use has declined due to safer alternatives.[26] In natural contexts, geminal diols feature in carbohydrate chemistry, where aldose sugars like glucose maintain an equilibrium between their open-chain aldehyde and hydrated forms, with hydrate-to-aldehyde ratios ranging from 1.5 to 13 across aldohexoses, facilitating reactions such as periodate oxidation for structural analysis.Spectroscopic Properties

1H NMR Spectroscopy

Geminal coupling constants () between protons attached to the same carbon atom in organic compounds typically range from -20 to +5 Hz; for unstrained sp³ CH₂ groups with innocuous substituents, the value is around -12 Hz, influenced by factors such as the H-C-H bond angle, substituents, and hybridization. In cases of free rotation around the C-X bonds, as in symmetric gem-dihalides (CHX), the two protons are chemically and magnetically equivalent, resulting in an effective Hz and no observable splitting in the H NMR spectrum. This equivalence arises because the rapid conformational averaging prevents differentiation of the protons' environments.[28] Electronegative geminal substituents, such as halogens, exert a strong deshielding effect on the attached protons, shifting their H NMR signals significantly downfield relative to unsubstituted alkanes like methane (δ 0.2 ppm). This deshielding increases with the electronegativity of the substituents, though it decreases down the halogen group due to inductive effects. For instance, in dichloromethane (CHCl), the methylene protons resonate at δ 5.3 ppm as a sharp singlet. Representative chemical shifts for common gem-dihalides are summarized below:| Compound | H Chemical Shift (δ, ppm) |

|---|---|

| CHF | 5.2 |

| CHCl | 5.3 |

| CHBr | 4.9 |

| CHI | 3.9 |