Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hydrogen halide

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

In chemistry, hydrogen halides (hydrohalic acids when in the aqueous phase) are diatomic, inorganic compounds that function as Arrhenius acids. The formula is HX where X is one of the halogens: fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, astatine, or tennessine.[1] All known hydrogen halides are gases at standard temperature and pressure.[2]

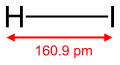

| Compound | Chemical formula | Bond length d(H−X) / pm (gas phase) |

model | Dipole μ / D |

Aqueous phase (acid) | Aqueous Phase pKa values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydrogen fluoride (fluorane) |

HF | 1.86 | hydrofluoric acid | 3.1 | ||

| hydrogen chloride (chlorane) |

HCl |  |

|

1.11 | hydrochloric acid | −3.9 |

| hydrogen bromide (bromane) |

HBr |  |

|

0.788 | hydrobromic acid | −5.8 |

| hydrogen iodide (iodane) |

HI |  |

|

0.382 | hydroiodic acid | −10.4 [3] |

| hydrogen astatide astatine hydride (astatane) |

HAt |  |

|

−0.06 | hydroastatic acid | ? |

| hydrogen tennesside tennessine hydride (tennessane) |

HTs |  |

−0.24 ? | hydrotennessic acid | ?[4] |

Comparison to hydrohalic acids

[edit]The hydrogen halides are diatomic molecules with no tendency to ionize in the gas phase (although liquified hydrogen fluoride is a polar solvent somewhat similar to water). Thus, chemists distinguish hydrogen chloride from hydrochloric acid. The former is a gas at room temperature that reacts with water to give the acid. Once the acid has formed, the diatomic molecule can be regenerated only with difficulty, but not by normal distillation. Commonly the names of the acid and the molecules are not clearly distinguished such that in lab jargon, "HCl" often means hydrochloric acid, not the gaseous hydrogen chloride.

Occurrence

[edit]Hydrogen chloride, in the form of hydrochloric acid, is a major component of gastric acid.

Hydrogen fluoride, chloride and bromide are also volcanic gases.

Synthesis

[edit]The direct reaction of hydrogen with fluorine and chlorine gives hydrogen fluoride and hydrogen chloride, respectively. Industrially these gases are, however, produced by treatment of halide salts with sulfuric acid. Hydrogen bromide arises when hydrogen and bromine are combined at high temperatures in the presence of a platinum catalyst. The least stable hydrogen halide, HI, is produced less directly, by the reaction of iodine with hydrogen sulfide or with hydrazine.[1]: 809–815

Physical properties

[edit]

The hydrogen halides are colourless gases at standard conditions for temperature and pressure (STP) except for hydrogen fluoride, which boils at 19 °C. Alone of the hydrogen halides, hydrogen fluoride exhibits hydrogen bonding between molecules, and therefore has the highest melting and boiling points of the HX series. From HCl to HI the boiling point rises. This trend is attributed to the increasing strength of intermolecular van der Waals forces, which correlates with numbers of electrons in the molecules. Concentrated hydrohalic acid solutions produce visible white fumes. This mist arises from the formation of tiny droplets of their concentrated aqueous solutions of the hydrohalic acid.

Reactions

[edit]Upon dissolution in water, which is highly exothermic, the hydrogen halides give the corresponding acids. These acids are very strong, reflecting their tendency to ionize in aqueous solution yielding hydronium ions (H3O+). With the exception of hydrofluoric acid, the hydrogen halides are strong acids, with acid strength increasing down the group. Hydrofluoric acid is complicated because its strength depends on the concentration owing to the effects of homoconjugation. As solutions in non-aqueous solvents, such as acetonitrile, the hydrogen halides are only modestly acidic however.

Similarly, the hydrogen halides react with ammonia (and other bases), forming ammonium halides:

- HX + NH3 → NH4X

In organic chemistry, the hydrohalogenation reaction is used to prepare halocarbons. For example, chloroethane is produced by hydrochlorination of ethylene:[5]

- C2H4 + HCl → CH3CH2Cl

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ The Acidity of the Hydrogen Halides. (2020, August 21). Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/3699

- ^ Schmid, Roland; Miah, Arzu M. (2001). "The Strength of the Hydrohalic Acids". Journal of Chemical Education. 78 (1). American Chemical Society (ACS): 116. Bibcode:2001JChEd..78..116S. doi:10.1021/ed078p116. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ de Farias, Robson Fernandes (January 2017). "Estimation of some physical properties for tennessine and tennessine hydride (TsH)". Chemical Physics Letters. 667: 1–3. Bibcode:2017CPL...667....1D. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2016.11.023.

- ^ M. Rossberg et al. "Chlorinated Hydrocarbons" in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2

Hydrogen halide

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and nomenclature

Hydrogen halides are diatomic molecules composed of one hydrogen atom bonded to one halogen atom, represented by the general formula HX, where X denotes a halogen from group 17 of the periodic table. The halogens include fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br), and iodine (I); astatine (At) is excluded due to its extreme rarity and radioactivity.[4][5] These group 17 elements are highly electronegative nonmetals that readily form covalent bonds with hydrogen, resulting in polar diatomic species.[6] As binary compounds consisting solely of hydrogen and a single halogen, hydrogen halides are classified both as binary acids—due to their capacity to release a proton—and as covalent hydrides of the halogens.[5][7] The nomenclature follows systematic IUPAC conventions, naming them as hydrogen followed by the halogen name: hydrogen fluoride (HF), hydrogen chloride (HCl), hydrogen bromide (HBr), and hydrogen iodide (HI). These abbreviations are widely used in chemical literature for brevity.[8] The discovery of hydrogen halides dates back to the 17th and 18th centuries, marking early advances in chemical synthesis and isolation. Hydrogen chloride was first prepared in 1648 by German chemist Johann Rudolf Glauber, who heated sodium chloride with sulfuric acid, producing the gas as a byproduct distinct from metal chloride salts.[9] In 1771, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated hydrogen fluoride by distilling fluorspar (calcium fluoride) with sulfuric acid, noting its unique etching properties on glass and recognizing it as a novel acidic substance separate from fluoride salts.[10] These early isolations highlighted the gaseous nature of hydrogen halides at standard conditions and laid the foundation for understanding their chemistry as pure compounds.[11]Comparison to hydrohalic acids

Hydrohalic acids are the aqueous solutions of hydrogen halides (HX), where X represents a halogen atom (F, Cl, Br, or I). For example, hydrochloric acid is the aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride, denoted as HCl(aq).[1] The anhydrous hydrogen halides exist primarily as molecular, diatomic gases at standard conditions, with hydrogen fluoride exhibiting a notably higher boiling point (19.5 °C) due to extensive hydrogen bonding, while the others (HCl, HBr, HI) are gases with lower boiling points. In contrast, hydrohalic acids are ionized in water, forming hydronium ions and halide ions: The completeness of this dissociation varies by halide; HF is a weak acid with partial ionization, whereas HCl, HBr, and HI are strong acids that fully dissociate.[12][1] Behaviorally, anhydrous hydrogen halides are employed in non-aqueous reactions, such as anhydrous HCl in pharmaceutical synthesis where moisture must be avoided, and they are typically stored as compressed gases or liquefied under pressure. Hydrohalic acids, however, are used in aqueous chemistry applications like pH adjustment or metal etching and are stored as liquid solutions, often at concentrations up to 38% for HCl to form azeotropes.[13][1] A unique aspect of HF arises from the fluoride ion's small size and high charge density, which promotes its reactivity in water to form complex ions such as the bifluoride ion [HF₂]⁻, enhancing its corrosive properties beyond simple proton donation.Sources

Natural occurrence

Hydrogen halides occur naturally in the atmosphere primarily through volcanic emissions, where HCl and HF are released as components of volcanic gases. Volcanoes emit HCl at concentrations up to 1-5% by volume in some fumarolic gases, contributing an estimated global flux of 0.4-11 Tg per year, while HF emissions are typically lower, around 0.06-6 Tg annually.[14] HBr and HI are less prominent in volcanic outputs but arise from sea spray aerosols and hydrothermal vents; sea salt debromination releases HBr into the troposphere, serving as a key source of reactive bromine.[15] In oceanic environments, hydrogen halides exist mainly as dissociated halide ions in seawater salts such as NaCl, KBr, and NaI. Chloride ions dominate at approximately 19 g/kg in open ocean water, comprising over half of the total salinity of 35 g/kg, while bromide and iodide are present at much lower levels (around 65 mg/kg and 60 µg/kg, respectively).[16] Biological sources include the accumulation of iodide in marine algae, particularly brown seaweeds, which can concentrate iodine up to thousands of times seawater levels, potentially releasing HI or related volatiles during decay or stress. Trace HF arises in plants through fluoride uptake from soil or atmospheric deposition, with species like tea and grapevines accumulating up to several hundred mg/kg in leaves under natural fluoride exposure.[17][18] Astatine halides do not occur naturally in significant amounts due to the element's extreme radioactivity and short half-lives, with trace astatine produced only as a decay product in uranium ores.[19] These natural emissions contribute to environmental processes, including acid rain formation from volcanic HCl, which dissolves in rainwater to lower pH near eruption sites, and limited ozone depletion primarily from chlorine and bromine species rather than HF, which remains largely inert in the stratosphere.[20][21]Synthesis

Hydrogen halides can be synthesized through both direct and indirect laboratory methods, as well as large-scale industrial processes. Historically, the preparation of hydrogen chloride (HCl) dates back to the 17th century, when German chemist Johann Rudolf Glauber heated a mixture of sodium chloride (common salt) and sulfuric acid (known as oil of vitriol) to produce HCl gas, marking one of the earliest practical methods for isolating the compound.[22] This approach laid the foundation for subsequent developments in halide synthesis. In laboratory settings, direct synthesis involves the exothermic reaction of hydrogen gas with the elemental halogen:where X represents F, Cl, Br, or I. For HCl, the reaction is initiated by an electric spark or exposure to light, as the mixture is explosive under certain conditions. Hydrogen bromide (HBr) and hydrogen iodide (HI) require platinum catalysts and elevated temperatures for efficient combination, while hydrogen fluoride (HF) demands specialized equipment due to its extreme reactivity with glass and most metals.[23] Indirect methods typically start from metal halides and a non-volatile acid to liberate the hydrogen halide gas. A common laboratory procedure for HCl involves heating sodium chloride with concentrated sulfuric acid at around 500°C:

Similar reactions apply to HBr and HI using sodium bromide or iodide, though HI synthesis prefers phosphoric acid (H3PO4) over sulfuric acid to prevent oxidation of iodide to iodine. These methods allow controlled generation of pure HX gases for experimental use.[24] On an industrial scale, HCl is predominantly produced as a byproduct of organic chlorination processes, such as the production of vinyl chloride or dichloromethane, generating approximately 10 million tons annually worldwide. The gas is captured and absorbed in water to form hydrochloric acid solutions. In contrast, HF is manufactured by reacting fluorspar (CaF2) with concentrated sulfuric acid in a rotary kiln or packed-bed reactor at elevated temperatures:

The HF vapor is then condensed and purified. HBr and HI see limited industrial production, often via direct synthesis or hydrolysis of phosphorus halides for niche applications.[25] Purification of the resulting hydrogen halides is essential for high-purity applications. HCl and HBr are typically purified by distillation, where impurities like moisture or residual acids are removed under controlled conditions to yield anhydrous gases. For HF, fractional distillation addresses challenges from its azeotrope with water (at 38% HF), often involving multiple stages or addition of sulfuric acid to break the azeotrope and produce anhydrous HF.[26][27] Safety considerations are paramount during synthesis due to inherent hazards. Direct combination of H2 and X2 (especially Cl2) poses explosion risks from ignition by light, heat, or sparks, necessitating inert atmospheres and remote initiation. HF synthesis and handling require corrosion-resistant nickel or Monel vessels, as it aggressively attacks glass, steel, and many alloys, leading to potential leaks or equipment failure.[28][29]

Properties

Physical properties

The hydrogen halides (HF, HCl, HBr, and HI) are all colorless, nonflammable gases at room temperature and standard pressure, though HF has a boiling point of 19.5°C, rendering it a liquid under conditions slightly below typical room temperature but still a gas above this threshold near standard temperature and pressure (STP).[30] Their melting and boiling points exhibit a general increasing trend from HCl to HI due to rising molecular weights, which enhance London dispersion forces; however, HF displays an anomaly with a significantly higher boiling point than expected, attributed to strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the highly electronegative fluorine and hydrogen atoms. Melting points follow a similar pattern, with HI highest and HCl lowest, influenced by intermolecular forces and molecular size. The following table summarizes these values:| Compound | Melting Point (°C) | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | -83.6 | 19.5 |

| HCl | -114.2 | -85.1 |

| HBr | -88.5 | -66.8 |

| HI | -50.8 | -35.6 |