Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of Jupiter trojans (Greek camp)

View on Wikipedia

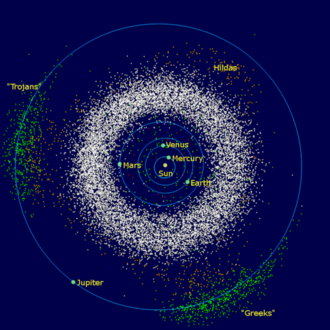

| Jupiter trojans Orbits of planets Sun | Hilda group Asteroid belt Near-Earth objects (some) |

This is a list of Jupiter trojans that lie in the Greek camp, an elongated curved region around the leading Lagrangian point (L4), 60° ahead of Jupiter in its orbit.

All the asteroids at Jupiter's L4 point have names corresponding to participants on the Greek side of the Trojan War, except for 624 Hektor, which was named before this naming convention was instituted. Correspondingly, 617 Patroclus is a Greek-named asteroid at the "Trojan" (L5) Lagrangian point. In 2018, at its 30th General Assembly in Vienna, the International Astronomical Union amended this naming convention, allowing Jupiter trojans with an H larger than 12 (that is, a mean diameter smaller than approximately 22 kilometers, for an assumed albedo of 0.057) to be named after Olympic athletes, as the number of known Jupiter trojans, currently more than 10,000, far exceeds the number of available names of heroes from the Trojan War in Greek mythology.[1][2][3]

Trojans in the Greek and Trojan camp are discovered mainly in turns, because they are separated by 120°, and for a period of time, one group of trojans will be behind the Sun, while the other will be visible.

Partial lists

[edit]As of July 2024[update], there are 8799 known objects in the Greek camp, of which 5099 are numbered and listed in the following partial lists:[2]

Largest members

[edit]This is a list of the largest 100+ Jupiter trojans of both the Greek and Trojan camps.

| Largest Jupiter Trojans by survey(A) (mean-diameter in kilometers; YoD: Year of Discovery) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | H | WISE | IRAS | Akari | Ln | RP | V–I | YoD | Ref |

| 624 Hektor | 7.2 | 225 | 233 | 230.99 | L4 | 6.92 | 0.930 | 1907 | list |

| 617 Patroclus | 8.19 | 140.362 | 140.92 | 140.85 | L5 | 102.80 | 0.830 | 1906 | list |

| 911 Agamemnon | 7.89 | 131.038 | 166.66 | 185.30 | L4 | 6.59 | 0.980 | 1919 | list |

| 588 Achilles | 8.67 | 130.099 | 135.47 | 133.22 | L4 | 7.31 | 0.940 | 1906 | list |

| 3451 Mentor | 8.4 | 126.288 | 116.30 | 117.91 | L5 | 7.70 | 0.770 | 1984 | list |

| 3317 Paris | 8.3 | 118.790 | 116.26 | 120.45 | L5 | 7.09 | 0.950 | 1984 | list |

| 1867 Deiphobus | 8.3 | 118.220 | 122.67 | 131.31 | L5 | 58.66 | 0.930 | 1971 | list |

| 1172 Äneas | 8.33 | 118.020 | 142.82 | 148.66 | L5 | 8.71 | 0.950 | 1930 | list |

| 1437 Diomedes | 8.3 | 117.786 | 164.31 | 172.60 | L4 | 24.49 | 0.810 | 1937 | list |

| 1143 Odysseus | 7.93 | 114.624 | 125.64 | 130.81 | L4 | 10.11 | 0.860 | 1930 | list |

| 2241 Alcathous | 8.64 | 113.682 | 114.63 | 118.87 | L5 | 7.69 | 0.940 | 1979 | list |

| 659 Nestor | 8.99 | 112.320 | 108.87 | 107.06 | L4 | 15.98 | 0.790 | 1908 | list |

| 3793 Leonteus | 8.7 | 112.046 | 86.26 | 87.58 | L4 | 5.62 | 0.780 | 1985 | list |

| 3063 Makhaon | 8.4 | 111.655 | 116.14 | 114.34 | L4 | 8.64 | 0.830 | 1983 | list |

| 1583 Antilochus | 8.6 | 108.842 | 101.62 | 111.69 | L4 | 31.54 | 0.950 | 1950 | list |

| 884 Priamus | 8.81 | 101.093 | 96.29 | 119.99 | L5 | 6.86 | 0.900 | 1917 | list |

| 1208 Troilus | 8.99 | 100.477 | 103.34 | 111.36 | L5 | 56.17 | 0.740 | 1931 | list |

| 1173 Anchises | 8.89 | 99.549 | 126.27 | 120.49 | L5 | 11.60 | 0.780 | 1930 | list |

| 2207 Antenor | 8.89 | 97.658 | 85.11 | 91.32 | L5 | 7.97 | 0.950 | 1977 | list |

| 2363 Cebriones | 9.11 | 95.976 | 81.84 | 84.61 | L5 | 20.05 | 0.910 | 1977 | list |

| 4063 Euforbo | 8.7 | 95.619 | 102.46 | 106.38 | L4 | 8.85 | 0.950 | 1989 | list |

| 2357 Phereclos | 8.94 | 94.625 | 94.90 | 98.45 | L5 | 14.39 | 0.960 | 1981 | list |

| 4709 Ennomos | 8.5 | 91.433 | 80.85 | 80.03 | L5 | 12.28 | 0.690 | 1988 | list |

| 2797 Teucer | 8.7 | 89.430 | 111.14 | 113.99 | L4 | 10.15 | 0.920 | 1981 | list |

| 2920 Automedon | 8.8 | 88.574 | 111.01 | 113.11 | L4 | 10.21 | 0.950 | 1981 | list |

| 15436 Dexius | 9.1 | 87.646 | 85.71 | 78.63 | L4 | 8.97 | 0.870 | 1998 | list |

| 3596 Meriones | 9.2 | 87.380 | 75.09 | 73.28 | L4 | 12.96 | 0.830 | 1985 | list |

| 2893 Peiroos | 9.23 | 86.884 | 87.46 | 86.76 | L5 | 8.96 | 0.950 | 1975 | list |

| 4086 Podalirius | 9.1 | 85.495 | 86.89 | 85.98 | L4 | 10.43 | 0.870 | 1985 | list |

| 4060 Deipylos | 9.3 | 84.043 | 79.21 | 86.79 | L4 | 9.30 | 0.760 | 1987 | list |

| 1404 Ajax | 9.3 | 83.990 | 81.69 | 96.34 | L4 | 29.38 | 0.960 | 1936 | list |

| 4348 Poulydamas | 9.5 | 82.032 | 70.08 | 87.51 | L5 | 9.91 | 0.840 | 1988 | list |

| 5144 Achates | 9.0 | 80.958 | 91.91 | 89.85 | L5 | 5.96 | 0.920 | 1991 | list |

| 4833 Meges | 8.9 | 80.165 | 87.33 | 89.39 | L4 | 14.25 | 0.940 | 1989 | list |

| 2223 Sarpedon | 9.41 | 77.480 | 94.63 | 108.21 | L5 | 22.74 | 0.880 | 1977 | list |

| 4489 Dracius | 9.0 | 76.595 | 92.93 | 95.02 | L4 | 12.58 | 0.950 | 1988 | list |

| 2260 Neoptolemus | 9.31 | 76.435 | 71.65 | 81.28 | L4 | 8.18 | 0.950 | 1975 | list |

| 5254 Ulysses | 9.2 | 76.147 | 78.34 | 80.00 | L4 | 28.72 | 0.970 | 1986 | list |

| 3708 Socus | 9.3 | 75.661 | 79.59 | 76.75 | L5 | 6.55 | 0.980 | 1974 | list |

| 2674 Pandarus | 9.1 | 74.267 | 98.10 | 101.72 | L5 | 8.48 | 1.000 | 1982 | list |

| 3564 Talthybius | 9.4 | 73.730 | 68.92 | 74.11 | L4 | 40.59 | 0.900 | 1985 | list |

| 4834 Thoas | 9.1 | 72.331 | 86.82 | 96.21 | L4 | 18.19 | 0.950 | 1989 | list |

| 7641 Cteatus | 9.4 | 71.839 | 68.97 | 75.28 | L4 | 27.77 | 0.980 | 1986 | list |

| 3540 Protesilaos | 9.3 | 70.225 | 76.84 | 87.66 | L4 | 8.95 | 0.940 | 1973 | list |

| 11395 Iphinous | 9.8 | 68.977 | 64.71 | 67.78 | L4 | 17.38 | – | 1998 | list |

| 4035 Thestor | 9.6 | 68.733 | 68.23 | 66.99 | L4 | 13.47 | 0.970 | 1986 | list |

| 5264 Telephus | 9.4 | 68.472 | 73.26 | 81.38 | L4 | 9.53 | 0.970 | 1991 | list |

| 1868 Thersites | 9.5 | 68.163 | 70.08 | 78.89 | L4 | 10.48 | 0.960 | 1960 | list |

| 9799 Thronium | 9.6 | 68.033 | 64.87 | 72.42 | L4 | 21.52 | 0.910 | 1996 | list |

| 4068 Menestheus | 9.5 | 67.625 | 62.37 | 68.46 | L4 | 14.40 | 0.950 | 1973 | list |

| 23135 Pheidas | 9.9 | 66.230 | 58.29 | 68.50 | L4 | 8.69 | 0.860 | 2000 | list |

| 2456 Palamedes | 9.3 | 65.916 | 91.66 | 99.60 | L4 | 7.24 | 0.920 | 1966 | list |

| 3709 Polypoites | 9.1 | 65.297 | 99.09 | 85.23 | L4 | 10.04 | 1.000 | 1985 | list |

| 1749 Telamon | 9.5 | 64.898 | 81.06 | 69.14 | L4 | 16.98 | 0.970 | 1949 | list |

| 3548 Eurybates | 9.6 | 63.885 | 72.14 | 68.40 | L4 | 8.71 | 0.730 | 1973 | list |

| 4543 Phoinix | 9.7 | 63.836 | 62.79 | 69.54 | L4 | 38.87 | 1.200 | 1989 | list |

| 12444 Prothoon | 9.8 | 63.835 | 64.31 | 62.41 | L5 | 15.82 | – | 1996 | list |

| 4836 Medon | 9.5 | 63.277 | 67.73 | 78.70 | L4 | 9.82 | 0.920 | 1989 | list |

| 16070 Charops | 9.7 | 63.191 | 64.13 | 68.98 | L5 | 20.24 | 0.960 | 1999 | list |

| 15440 Eioneus | 9.6 | 62.519 | 66.48 | 71.88 | L4 | 21.43 | 0.970 | 1998 | list |

| 4715 Medesicaste | 9.7 | 62.097 | 63.91 | 65.93 | L5 | 8.81 | 0.850 | 1989 | list |

| 34746 Thoon | 9.8 | 61.684 | 60.51 | 63.63 | L5 | 19.63 | 0.950 | 2001 | list |

| 38050 Bias | 9.8 | 61.603 | 61.04 | 50.44 | L4 | 18.85 | 0.990 | 1998 | list |

| 5130 Ilioneus | 9.7 | 60.711 | 59.40 | 52.49 | L5 | 14.77 | 0.960 | 1989 | list |

| 5027 Androgeos | 9.6 | 59.786 | 57.86 | n.a. | L4 | 11.38 | 0.910 | 1988 | list |

| 6090 Aulis | 9.4 | 59.568 | 74.53 | 81.92 | L4 | 18.48 | 0.980 | 1989 | list |

| 5648 Axius | 9.7 | 59.295 | 63.91 | n.a. | L5 | 37.56 | 0.900 | 1990 | list |

| 7119 Hiera | 9.7 | 59.150 | 76.40 | 77.29 | L4 | 400 | 0.950 | 1989 | list |

| 4805 Asteropaios | 10.0 | 57.647 | 53.16 | 43.44 | L5 | 12.37 | – | 1990 | list |

| 16974 Iphthime | 9.8 | 57.341 | 55.43 | 57.15 | L4 | 78.9 | 0.960 | 1998 | list |

| 4867 Polites | 9.8 | 57.251 | 58.29 | 64.29 | L5 | 11.24 | 1.010 | 1989 | list |

| 2895 Memnon | 10.0 | 56.706 | 55.67 | n.a. | L5 | 7.50 | 0.710 | 1981 | list |

| 4708 Polydoros | 9.9 | 54.964 | 55.67 | n.a. | L5 | 7.52 | 0.960 | 1988 | list |

| 21601 Aias | 10.0 | 54.909 | 55.67 | 56.08 | L4 | 12.65 | 0.970 | 1998 | list |

| 12929 Periboea | 9.9 | 54.077 | 61.04 | 55.34 | L5 | 9.27 | 0.880 | 1999 | list |

| 17492 Hippasos | 10.0 | 53.975 | 55.67 | n.a. | L5 | 17.75 | – | 1991 | list |

| 5652 Amphimachus | 10.1 | 53.921 | 53.16 | 52.48 | L4 | 8.37 | 1.050 | 1992 | list |

| 2759 Idomeneus | 9.9 | 53.676 | 61.01 | 52.55 | L4 | 32.38 | 0.910 | 1980 | list |

| 5258 Rhoeo | 10.2 | 53.275 | 50.77 | n.a. | L4 | 19.85 | 1.010 | 1989 | list |

| 12126 Chersidamas | 10.1 | 53.202 | n.a. | n.a. | L5 | n.a. | ? | 1999 | list |

| 15502 Hypeirochus | 10.0 | 53.100 | 55.67 | 50.86 | L5 | 15.13 | 0.875 | 1999 | list |

| 4754 Panthoos | 10.0 | 53.025 | 53.15 | 56.96 | L5 | 27.68 | – | 1977 | list |

| 4832 Palinurus | 10.0 | 52.058 | 53.16 | n.a. | L5 | 5.32 | 1.000 | 1988 | list |

| 5126 Achaemenides | 10.5 | 51.922 | 44.22 | 48.57 | L4 | 53.02 | – | 1989 | list |

| 3240 Laocoon | 10.2 | 51.695 | 50.77 | n.a. | L5 | 11.31 | 0.880 | 1978 | list |

| 4902 Thessandrus | 9.8 | 51.263 | 61.04 | 71.79 | L4 | 738 | 0.960 | 1989 | list |

| 11552 Boucolion | 10.1 | 51.136 | 53.16 | 53.91 | L5 | 32.44 | – | 1993 | list |

| 20729 Opheltius | 10.4 | 50.961 | 46.30 | n.a. | L4 | 5.72 | 1.000 | 1999 | list |

| 6545 Leitus | 10.1 | 50.951 | 53.16 | n.a. | L4 | 16.26 | 0.910 | 1986 | list |

| 4792 Lykaon | 10.1 | 50.870 | 53.16 | n.a. | L5 | 40.09 | 0.960 | 1988 | list |

| 21900 Orus | 10.0 | 50.810 | 55.67 | 53.87 | L4 | 13.45 | 0.950 | 1999 | list |

| 1873 Agenor | 10.1 | 50.799 | 53.76 | 54.38 | L5 | 20.60 | – | 1971 | list |

| 5028 Halaesus | 10.2 | 50.770 | 50.77 | n.a. | L4 | 24.94 | 0.900 | 1988 | list |

| 2146 Stentor | 9.9 | 50.755 | 58.29 | n.a. | L4 | 16.40 | – | 1976 | list |

| 4722 Agelaos | 10.0 | 50.378 | 53.16 | 59.47 | L5 | 18.44 | 0.910 | 1977 | list |

| 5284 Orsilocus | 10.1 | 50.159 | 53.16 | n.a. | L4 | 10.31 | 0.970 | 1989 | list |

| 11509 Thersilochos | 10.1 | 49.960 | 53.16 | 56.23 | L5 | 17.37 | – | 1990 | list |

| 5285 Krethon | 10.1 | 49.606 | 58.53 | 52.61 | L4 | 12.04 | 1.090 | 1989 | list |

| 4791 Iphidamas | 10.1 | 49.528 | 57.85 | 59.96 | L5 | 9.70 | 1.030 | 1988 | list |

| 9023 Mnesthus | 10.1 | 49.151 | 50.77 | 60.80 | L5 | 30.66 | – | 1988 | list |

| 5283 Pyrrhus | 9.7 | 48.356 | 64.58 | 69.93 | L4 | 7.32 | 0.950 | 1989 | list |

| 4946 Askalaphus | 10.2 | 48.209 | 52.71 | 66.10 | L4 | 22.73 | 0.940 | 1988 | list |

| 22149 Cinyras | 10.2 | 48.190 | 50.77 | 50.37 | L4 | 7.84 | 1.090 | 2000 | list |

| 32496 Deïopites | 10.2 | 48.017 | 50.77 | 51.63 | L5 | 23.34 | 0.950 | 2000 | list |

| 5120 Bitias | 10.2 | 47.987 | 50.77 | n.a. | L5 | 15.21 | 0.780 | 1988 | list |

| 12714 Alkimos | 10.1 | 47.819 | 61.04 | 54.62 | L4 | 28.48 | – | 1991 | list |

| 7352 Hypsenor | 9.9 | 47.731 | 55.67 | 47.07 | L5 | 648 | 0.850 | 1994 | list |

| 1870 Glaukos | 10.6 | 47.649 | 42.23 | n.a. | L5 | 5.99 | — | 1971 | list |

| 4138 Kalchas | 10.1 | 46.462 | 53.16 | 61.04 | L4 | 29.2 | 0.810 | 1973 | list |

| 23958 Theronice | 10.2 | 46.001 | 50.77 | 47.91 | L4 | 562 | 0.990 | 1998 | list |

| 4828 Misenus | 10.4 | 45.954 | 46.30 | 43.22 | L5 | 12.87 | 0.920 | 1988 | list |

| 4057 Demophon | 10.1 | 45.683 | 53.16 | n.a. | L4 | 29.82 | 1.060 | 1985 | list |

| 4501 Eurypylos | 10.4 | 45.524 | 46.30 | n.a. | L4 | 6.05 | – | 1989 | list |

| 4007 Euryalos | 10.3 | 45.515 | 48.48 | 53.89 | L4 | 6.39 | – | 1973 | list |

| 5259 Epeigeus | 10.3 | 44.741 | 42.59 | 44.42 | L4 | 18.42 | – | 1989 | list |

| 30705 Idaios | 10.4 | 44.546 | 46.30 | n.a. | L5 | 15.74 | – | 1977 | list |

| 16560 Daitor | 10.7 | 43.861 | 51.42 | 43.38 | L5 | – | – | 1991 | list |

| 15977 Pyraechmes | 10.4 | 43.530 | 46.30 | 51.53 | L5 | 250 | 0.906 | 1998 | list |

| 7543 Prylis | 10.6 | 42.893 | 42.23 | n.a. | L4 | 17.80 | – | 1973 | list |

| 4827 Dares | 10.5 | 42.770 | 44.22 | n.a. | L5 | 19.00 | – | 1988 | list |

| 1647 Menelaus | 10.5 | 42.716 | 44.22 | n.a. | L4 | 17.74 | 0.866 | 1957 | list |

| (A) Used sources: WISE/NEOWISE catalog (NEOWISE_DIAM_V1 PDS, Grav, 2012); IRAS data (SIMPS v.6 catalog); and Akari catalog (Usui, 2011); RP: rotation period and V–I (color index) taken from the LCDB

Note: missing data was completed with figures from the JPL SBDB (query) and from the LCDB (query form) for the WISE/NEOWISE and SIMPS catalogs, respectively. These figures are given in italics. Also, listing is incomplete above #100. | |||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ "MPEC 2024-P10 : DAILY ORBIT UPDATE". Minor Planet Electronic Circular. 1 August 2024. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b "List of Jupiter Trojans". Minor Planet Center. 19 July 2024. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ "Asteroid Size Estimator". CNEOS NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

List of Jupiter trojans (Greek camp)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and orbital position

Jupiter Trojans are small Solar System bodies that share Jupiter's heliocentric orbit, maintained in stable 1:1 mean motion resonance by librating around the planet's L4 or L5 Lagrangian points due to the balanced gravitational influences of the Sun and Jupiter. These points represent equilibrium locations in the circular restricted three-body problem, where the effective potential allows asteroids to oscillate without escaping for billions of years.[1][5] The Greek camp denotes the population of Trojans at the L4 Lagrangian point, situated roughly 60° ahead of Jupiter along its orbital path. This swarm occupies an elongated, tadpole-shaped domain formed by the libration of member orbits around L4, with the narrow "head" centered at the point and the broader "tail" extending asymmetrically in the direction of Jupiter's motion.[6][7] Greek camp Trojans exhibit orbital elements closely matching Jupiter's, including a semi-major axis of approximately 5.2 AU, low eccentricities below 0.1 for the majority, and inclinations relative to the ecliptic plane reaching up to 40°.[5][8] This distinguishes them from the Trojan camp at L5, located about 60° behind Jupiter, as well as from other Jupiter-resonant populations such as the Hildas, which occupy a 3:2 mean motion resonance at semi-major axes near 4 AU.[6][9]Discovery and naming conventions

The first Jupiter Trojan in the Greek camp, located at the L4 Lagrangian point ahead of the planet, was discovered on February 22, 1906, by German astronomer Max Wolf using photographic plates at Heidelberg Observatory; this object was later designated 588 Achilles after the Greek hero from Homer's Iliad.[10] Shortly thereafter, on February 10, 1907, August Kopff discovered another L4 Trojan at the same observatory, provisionally designated 1907 XM and soon numbered 624 Hektor.[11] These early finds were initially viewed as anomalous due to their unusual orbits sharing Jupiter's path, but they confirmed theoretical predictions of stable swarms at the planet's Lagrangian points made by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1772. Between 1906 and 1921, astronomers identified several prominent Greek camp Trojans through continued photographic observations, including 659 Nestor (discovered March 23, 1908, by Max Wolf) and others like 911 Agamemnon (March 19, 1919, by Karl Reinmuth). Discoveries remained sporadic during this period, with only about a dozen confirmed by the 1920s, as detection relied on manual scanning of glass photographic plates exposed over long nights.[12] The naming convention for L4 Trojans, established soon after these initial discoveries, requires names drawn from Greek mythology, specifically figures associated with the Greek side of the Trojan War, such as heroes like Odysseus (1143 Odysseus, discovered 1930).[1] The exception is 624 Hektor, named for a Trojan prince in violation of the later standard, as it predated the formal guideline proposed by Johann Palisa in 1906.[12] Upon orbital confirmation, the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center assigns sequential numbers to these objects, integrating them into the broader catalog of minor planets. Detection methods advanced significantly from visual and photographic techniques to charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging in the late 1980s and 1990s, enabling automated surveys to scan wider sky areas with greater sensitivity.[12] This shift spurred a post-1990 surge in discoveries, driven by programs like Spacewatch (operational since 1984 at Kitt Peak National Observatory) and the Catalina Sky Survey (initiated in 1998), which have collectively identified thousands of faint Trojans previously undetectable. As of November 2025, over 15,000 Jupiter Trojans are known in total, with the Greek camp comprising the majority due to observational biases and dynamical factors.[7][3]Population and characteristics

Current known count and estimates

As of November 2025, 9,694 Jupiter trojans in the Greek camp have been identified, comprising about 63% of the total known population of 15,357 Jupiter trojans across both camps.[13][14] Of these Greek camp objects, around 5,100 have received permanent numerical designations from the Minor Planet Center based on sufficiently precise orbital determinations.[15] The discovery history of Greek camp trojans reflects steady growth driven by advancing observational technology. In the mid-20th century, around 1950, fewer than 100 were known, increasing to 257 by 2000 and over 1,000 by 2003 through dedicated photographic surveys. This pace accelerated dramatically in the 21st century, with major contributions from wide-field surveys such as Pan-STARRS1, which cataloged thousands of faint objects, and early data from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), operational since 2025 and projected to uncover hundreds of thousands more.[16] Current estimates suggest the total population of Jupiter trojans exceeds 1 million objects with diameters greater than 1 km, with the Greek camp likely comprising the majority due to observational biases that favor detection in the L4 region, such as its position in the evening sky for Northern Hemisphere telescopes.[17] Observational completeness is estimated at over 90% for trojans larger than 100 km in diameter, where only a handful of the largest members remain undetected, but falls to about 50% for those exceeding 10 km, reflecting challenges in surveying fainter, smaller bodies.[18] All known Greek camp trojans reside in stable tadpole orbits librating around the L4 Lagrangian point. The overall distribution shows a slight asymmetry, with the Greek camp outnumbering the Trojan camp by approximately 1.7 to 1, attributed to both dynamical effects from Jupiter's early outward migration and persistent observational preferences for the leading swarm.[7][19]Size and compositional overview

The sizes of Jupiter trojans in the Greek camp range from approximately 250 km for the largest members down to sub-kilometer objects, reflecting a broad spectrum of planetesimal remnants captured in the L4 Lagrangian point. The cumulative size distribution for these bodies follows a power-law form, with an index of q ≈ -5 for diameters greater than 100 km, transitioning to a shallower slope of q ≈ -2.1 in the 10–100 km range, indicating fewer large bodies and a relative abundance of intermediates; for diameters above 5 km, the overall index approximates 3.5, consistent with collisional evolution over billions of years. This distribution underscores the Greek camp's similarity to the Trojan camp, with no significant asymmetry in size frequencies between the two swarms.[20] In terms of shapes, many Greek camp trojans exhibit elongated or irregular forms, with contact binaries being a common configuration among the population, as evidenced by their low bulk densities and photometric variability.[21] Rotation periods typically span 5–20 hours, though some display non-principal axis rotation characteristic of tumblers, contributing to complex lightcurve behaviors observed in surveys.[21] Compositionally, the Greek camp is dominated by D-type asteroids, comprising about 73% of the population under the Bus-DeMeo taxonomy, with primitive carbonaceous types such as P- and C-types making up roughly 20%, and a small fraction of S-types or X-types. These bodies display uniformly low albedos in the range of 0.04–0.10, averaging around 0.053, which aligns with their dark, primitive surfaces.[22] Spectroscopic analyses reveal featureless, red-sloped spectra indicative of fine-grained silicates and possible organic materials, with tentative evidence for hydration features like N-H absorptions near 3.1 μm, though no prominent water ice signatures are confirmed in visible-near-infrared observations.[22] Greek camp trojans share compositional affinities with outer main-belt asteroids, particularly in their D- and P-type classifications, but exhibit redder spectral slopes overall, suggesting a distinct processing history or source material.[8] As potential primordial planetesimals from the early Kuiper belt, captured during giant planet migrations, they preserve icy, organic-rich compositions that offer insights into solar system formation.[8]Notable members

Largest by diameter

The largest members of the Jupiter Trojans in the Greek camp, located at the L4 Lagrangian point ahead of Jupiter, are primarily primitive D- and P-type asteroids with diameters exceeding 100 km. These objects represent the most massive and voluminous in the swarm, offering insights into the early solar system's planetesimal population captured during planetary migration. Diameters are estimated using a combination of thermal infrared radiometry, which assumes spherical shapes for volume-equivalent sizes, and direct shape modeling from adaptive optics or occultations for irregular bodies. The top-ranked examples highlight the diversity in shapes, including binaries and elongated forms, with Hektor standing out as the dominant body.| Rank | Designation and Name | Estimated Diameter (km) | Discovery Year | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (624) Hektor | 225 ± 20 | 1907 | Contact binary with satellite Skamandrios (∼12 km diameter); bilobed shape (∼370 × 200 × 150 km axes); density ∼1.0 g/cm³ |

| 2 | (911) Agamemnon | 166 ± 10 | 1919 | Elongated (190.6 × 143.8 km from occultation); possible satellite (∼5 km) |

| 3 | (588) Achilles | 131 ± 8 | 1906 | Irregular shape from lightcurves; rotation period ∼17.4 hours |

| 4 | (1867) Deiphobus | 118 ± 10 | 1971 | Low albedo (∼0.06); primitive composition |

| 5 | (1172) Aeneas | 118 ± 8 | 1931 | Assumed spherical; albedo ∼0.06 |

| 6 | (1143) Odysseus | 115 ± 6 | 1930 | Rotation period ∼10.2 hours; potential regolith coverage |

| 7 | (659) Nestor | 112 ± 10 | 1908 | Low albedo (∼0.04); impact cratered surface inferred |

| 8 | (884) Priamus | 101 ± 5 | 1917 | Assumed spherical; low density inferred |

| 9 | (1208) Troilus | 100 ± 8 | 1931 | Albedo ∼0.04; primitive spectral type |

| 10 | (1173) Anchises | 100 ± 7 | 1931 | Albedo ∼0.05; unstable orbit on longer timescales |

Targets of space missions

The NASA Lucy mission, launched on October 16, 2021, represents the first spacecraft dedicated to exploring Jupiter's Trojan asteroids, including four targets in the Greek camp at the L4 Lagrange point.[26] These targets were selected for their diverse taxonomic types (C-type, P-type, and D-type), sizes ranging from 21 km to 64 km in diameter, and potential to represent the broader population of the swarm, providing insights into the Trojans' origins and evolution.[27] The mission's trajectory includes flybys of these objects during 2027–2028, following Earth gravity assists and a main-belt asteroid encounter in April 2025; as of November 2025, Lucy remains en route to the Greek camp with no Trojan flybys completed yet. The first Greek camp target is (3548) Eurybates, a 64 km-diameter C-type asteroid and the largest in Lucy's Trojan portfolio, with a flyby scheduled for August 2027 at a closest approach of about 1,000 km.[27] Eurybates, accompanied by its 1 km satellite Queta, belongs to a collisional family, and the encounter will use the spacecraft's instruments—including the L'LORRI imager, L'RISS high-resolution camera, and L'SS thermal emission spectrometer—for multispectral imaging, shape modeling, and compositional analysis to investigate why only C-type families dominate among Trojans.[28] Following closely, on September 15, 2027, Lucy will fly by (15094) Polymele, a smaller 21 km P-type asteroid rich in organics, at a distance of around 415 km, marking the first spacecraft visit to this spectral class; objectives include detecting potential satellites (a 5 km moon, nicknamed Shaun, was identified pre-flyby) and studying surface volatiles via spectroscopy.[27] In 2028, the mission targets two D-type asteroids: (11351) Leucus, a 40 km elongated body with an unusually slow 446-hour rotation, for a April flyby at 1,011 km to examine thermal properties and shape via thermal infrared observations; and (21900) Orus, a 51 km dark, reddish object, for a November flyby at 1,500 km to compare organic compositions and binary fractions with Leucus and other targets.[27] Overall, Lucy's Greek camp objectives focus on high-resolution imaging, visible- and infrared spectroscopy, and thermal mapping to determine shapes, surface compositions, crater distributions, and satellite presence, thereby constraining models of Trojan formation during the early Solar System, binary system prevalence (estimated at 20–30% in the population), and surface alteration processes over billions of years.[28] No other space missions have targeted Greek camp Trojans to date, with historical exploration limited to ground- and space-based telescopic observations rather than close flybys, unlike the Trojan camp's (617) Patroclus which awaits its first spacecraft visit later in Lucy's itinerary.[26] Proposed concepts, such as a 2012 French-led ESA reconnaissance mission for multiple Greek camp flybys, have not advanced to launch, though future opportunities like extended Lucy operations or new proposals could expand exploration of this swarm.[29]Partial lists

Numbered trojans 1–10,000

The numbered Jupiter trojans in the Greek camp with permanent designations from 1 to 10,000 represent the earliest discovered and best-studied members of this population, totaling approximately 1,013 objects as of late 2025.[3] These low-numbered trojans, primarily identified between 1906 and the early 2000s, form the foundational catalog of the L4 swarm and include many of the largest and most prominent bodies, such as (588) Achilles and (624) Hektor. Their discovery predates modern surveys, with most observed using ground-based telescopes before systematic sky patrols like those from the Catalina Sky Survey accelerated findings post-2000.[30][31] This subset exhibits a higher proportion of large-diameter objects compared to higher-numbered trojans, with about 10% exceeding 100 km in size, reflecting observational biases toward brighter, more accessible targets in the early 20th century. Spectrally, roughly 70-80% are classified as D-type asteroids, characterized by reddish colors and low albedos typical of primitive, carbon-rich compositions, while the remainder include P-type and rarer C-type variants.[33] Binaries are present but infrequent, with notable examples like (624) Hektor, which orbits a smaller satellite named Skamandrios, providing insights into Trojan formation and density (estimated at 2.2 g/cm³ for Hektor). These early trojans, often named after Greek figures from the Iliad such as Achilles and Nestor, highlight the pioneering phase of Trojan astronomy and serve as references for dynamical models of the L4 population. For reference, the following table lists the first 17 numbered Greek camp trojans by permanent designation (corrected to remove non-Trojan entries), including estimated mean diameters derived from infrared observations and discovery years. Diameters are approximate and assume typical albedos of 0.05-0.10 for D-types.[34]| Number | Name | Discovery Year | Diameter (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 588 | Achilles | 1906 | ~135 |

| 624 | Hektor | 1907 | ~225 |

| 659 | Nestor | 1908 | ~120 |

| 911 | Agamemnon | 1919 | ~166 |

| 1143 | Odysseus | 1930 | ~180 |

| 1172 | Aeneas | 1930 | ~150 |

| 1208 | Troilus | 1931 | ~135 |

| 1404 | Ajax | 1936 | ~123 |

| 1437 | Diomedes | 1937 | ~177 |

| 1583 | Antilochus | 1950 | ~130 |

| 1749 | Telamon | 1949 | ~115 |

| 1870 | Protesilaos | 1948 | ~45 |

| 2113 | Epimetheus | 1952 | ~80 |

| 2456 | Palamedes | 1978 | ~70 |

| 2597 | Artemis | 1978 | ~55 |

| 2797 | Teucer | 1971 | ~100 |

Numbered trojans 10,001 and above

The numbered Jupiter Trojans in the Greek camp with permanent designations 10,001 and above represent recent additions to the catalog, totaling over 3,500 objects as of 2025 and extending up to approximately 700,000. These high-numbered entries are primarily products of automated sky surveys conducted after 2010, including the Catalina Sky Survey and Pan-STARRS, which have systematically detected faint objects in the L4 region through wide-field imaging and follow-up observations. Unlike earlier discoveries focused on brighter targets, these surveys have prioritized completeness in magnitude-limited samples, leading to a rapid increase in the known population.[31] In the Minor Planet Center database, these Trojans are organized sequentially by number and often grouped into ranges for reference, such as 10,001–50,000 (encompassing early 21st-century finds), 50,001–100,000 (from mid-decade expansions), and higher brackets like 500,001–700,000 (reflecting ongoing numbering from recent data). Most lack mythological names, as naming conventions reserve them for objects with sufficient observational history or scientific interest; instead, they retain numerical designations post-orbit computation. Representative examples include (10052) Euantes in the 10,001–50,000 range and higher entries like those in the 500,000 series, which illustrate the catalog's growth driven by survey efficiency. Key trends among these higher-numbered Trojans include smaller average sizes, with diameters typically under 20 km corresponding to absolute magnitudes H > 12, due to observational biases favoring larger bodies in pre-2010 searches. Orbital elements show increasing diversity, with libration amplitudes spanning 10°–40° and eccentricities up to 0.2, revealing a broader phase-space occupation than in low-numbered samples, as bias-corrected distributions from decade-long surveys indicate. Approximately 60% of these objects have been observed on only a single occasion, limiting initial orbit quality and delaying full characterization. Challenges in studying these Trojans stem from their faintness (V > 20 mag at opposition), which complicates precise orbital determination and requires extended observation arcs for reliable numbering; many initially receive provisional status before confirmation. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), operational since 2025, is poised to address this by delivering multi-year light curves for over 100,000 Trojans, enabling the numbering of tens of thousands more and refining orbits for the Greek camp population.[36]Provisionally designated trojans

Provisionally designated Jupiter trojans in the Greek camp consist of unnumbered objects identified through short-term observations that confirm their libration around the L4 Lagrangian point, approximately 60° ahead of Jupiter. As of 2025, over 3,000 such objects have been cataloged by the Minor Planet Center, bearing temporary designations in the format YYYY CCNN (e.g., 2016 BV13), often based on single- or few-night astrometric data from surveys like Pan-STARRS and the Catalina Sky Survey. These detections typically require verification of co-orbital motion with Jupiter, distinguishing them from main-belt interlopers.[37][31] Confirmation of Trojan status involves astrometric follow-up to measure orbital elements, ensuring a semi-major axis near 5.2 AU and libration amplitude less than 30° around L4. Networks such as the NEO Confirmation Network (NEOCam, now NEO Surveyor) and amateur observatories provide critical observations to refine orbits and prevent loss. The Minor Planet Center assigns provisional designations upon initial reporting, with Trojan classification based on dynamical simulations showing stable tadpole orbits. Once sufficient observations (typically 3-4 oppositions) accumulate, objects qualify for permanent numbering.[7] These objects are generally faint, with apparent magnitudes exceeding V=20, limiting observations to large telescopes and making recovery challenging; approximately 20% become lost due to insufficient follow-up before fading from view. They are predominantly small, under 10 km in diameter, with estimated sizes derived from absolute magnitudes assuming albedos around 0.05-0.1. This faint, diminutive nature highlights their high potential for future numbering as survey sensitivities improve, potentially doubling the known population in the coming decade.[31][38] Recent additions from 2020–2025, driven by enhanced wide-field surveys, have expanded the catalog significantly. Objects are grouped by discovery year for organizational purposes, with rough orbital parameters (semi-major axis a ≈ 5.20 AU, eccentricity e < 0.15, inclination i < 40°) confirming L4 residency. The following table presents representative examples, including estimated diameters from thermal models where available.| Provisional Designation | Discovery Year | Survey | Semi-Major Axis (AU) | Est. Diameter (km) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 FW14 | 2023 | Pan-STARRS | 5.20 | ~2-5 | Short arc; L4 confirmed via dynamical fit. |

| 2016 BV13 | 2016 | Catalina | 5.19 | <5 | Few-night detection; high libration amplitude ~25°.[31] |

| 1999 XT160 | 1999 | NEAT | 5.21 | ~4 | Eurybates family member; unrecovered risk noted.[38] |

| 1989 AU1 | 1989 | Palomar | 5.20 | ~3-6 | Early provisional; orbit refined over years.[38] |

| 1973 SO | 1973 | Palomar | 5.22 | ~5 | Historic faint detection; stable L4 libration.[38] |

References

- https://www.jpl.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/news/nasas-wise-colors-in-unknowns-on-jupiter-asteroids/