Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Europa Clipper

View on Wikipedia

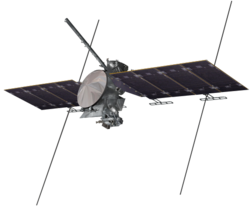

Artist's rendering of the Europa Clipper spacecraft | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Names | Europa Multiple Flyby Mission | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Europa reconnaissance | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Jet Propulsion Laboratory | ||||||||||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2024-182A | ||||||||||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 61507 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | europa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mission duration | Cruise: 5.5 years[1][2] Science phase: 4 years Elapsed: 1 year, 25 days | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 6,065 kg (13,371 lb),[3][4] including 2,750 kg (6,060 lb) propellant[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dry mass | 3,241 kg (7,145 lb)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Payload mass | 352 kg (776 lb) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dimensions | Height: 5 m (16 ft) Solar panel span: 30.5 m (100 ft)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Power | 600 watts from solar panels[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch date | October 14, 2024, 16:06:00 UTC (12:06 p.m. EDT) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rocket | Falcon Heavy Block 5[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39A | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Contractor | SpaceX | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Mars (gravity assist) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | March 1, 2025, 17:57 UTC (12:57 p.m. EST)[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 884 km (549 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Earth (gravity assist) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | December 3, 2026 4:15 PM EST[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Jupiter orbiter | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Orbital insertion | April 11, 2030 (first closest approach to Europa)[11] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Orbits | 49[6][12] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Europa Clipper mission patch Large Strategic Science Missions Planetary Science Division | |||||||||||||||||||||

Europa Clipper (previously known as Europa Multiple Flyby Mission) is a space probe developed by NASA to study Europa, a Galilean moon of Jupiter. It was launched on October 14, 2024.[14] The spacecraft used a gravity assist from Mars on March 1, 2025,[9] and it will use a gravity assist from Earth on December 3, 2026,[10] before arriving at Europa in April 2030.[15] The spacecraft will then perform a series of flybys of Europa while orbiting Jupiter.[16][17]

Europa Clipper is designed to study evidence for a subsurface ocean underneath Europa's ice crust, found by the Galileo spacecraft which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. Plans to send a spacecraft to Europa were conceived with projects such as Europa Orbiter and Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter, in which a spacecraft would be inserted into orbit around Europa. However, due to the effects of radiation from the magnetosphere of Jupiter in Europa orbit, it was decided that it would be safer to insert a spacecraft into an elliptical orbit around Jupiter and make 49 close flybys of the moon instead.[18] The Europa Clipper spacecraft is larger than any previous spacecraft for NASA planetary missions.[19]

The orbiter will analyze the induced magnetic field around Europa, and attempt to detect plumes of water ejecta from a subsurface ocean; in addition to various other tests.[20]

The mission's name is a reference to the lightweight, fast clipper ships of the 19th century that routinely plied trade routes, since the spacecraft will pass by Europa at a rapid cadence, as frequently as every two weeks. The mission patch, which depicts a sailing ship, references the moniker.[21]

Europa Clipper complements the ESA's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, launched in 2023, which will attempt to fly past Europa twice and Callisto multiple times before moving into orbit around Ganymede.

History

[edit]Early proposals and Galileo discoveries

[edit]In 1997, a Europa Orbiter mission was proposed by a team for NASA's Discovery Program[22] but was not selected. NASA's JPL announced one month after the selection of Discovery proposals that a NASA Europa orbiter mission would be conducted. JPL then invited the Discovery proposal team to be the Mission Review Committee (MRC).[citation needed]

At the same time as the proposal of the Discovery-class Europa Orbiter, the robotic Galileo spacecraft was already orbiting Jupiter. From December 8, 1995, to December 7, 1997, Galileo conducted the primary mission after entering the orbit of Jupiter. On that final date, the Galileo orbiter commenced an extended mission known as the Galileo Europa Mission (GEM), which ran until December 31, 1999. This was a low-cost mission extension with a budget of only US$30 million. The smaller team of about 40–50 people (compared with the primary mission's 200-person team from 1995 to 1997) did not have the resources to deal with problems, but when they arose, it was able to temporarily recall former team members (called "tiger teams") for intensive efforts to solve them. The spacecraft made several flybys of Europa (8), Callisto (4) and Io (2). On each flyby of the three moons it encountered, the spacecraft collected only two days' worth of data instead of the seven it had collected during the primary mission.[23] During GEM's eight flybys of Europa, it ranged from 196 to 3,582 km (122 to 2,226 mi), in two years.[23]

Europa has been identified as one of the locations in the Solar System that could possibly harbor microbial extraterrestrial life.[24][25][26] Immediately following the Galileo spacecraft's discoveries and the independent Discovery program proposal for a Europa orbiter, JPL conducted preliminary mission studies that envisioned a capable spacecraft such as the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (a US$16 billion mission concept),[27] the Jupiter Europa Orbiter (a US$4.3 billion concept), another orbiter (US$2 billion concept), and a multi-flyby spacecraft: Europa Clipper.[28]

A mission to Europa was recommended by the National Research Council in 2013.[24][26] The approximate cost estimate rose from US$2 billion in 2013 to US$4.25 billion in 2020.[29][30] The mission is a joint project between the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[1][31]

Funding put forward

[edit]In March 2013, US$75 million was authorized to expand on the formulation of mission activities, mature the proposed science goals, and fund preliminary instrument development,[32] as suggested in 2011 by the Planetary Science Decadal Survey.[1][26] In May 2014, a House bill substantially increased the Europa Clipper (referred to as Europa Multiple Flyby Mission) funding budget for the 2014 fiscal year from US$15 million[33][34] to US$100 million to be applied to pre-formulation work.[35][36] Following the 2014 election cycle, bipartisan support was pledged to continue funding for the Europa Multiple Flyby Mission project.[37][38] The executive branch also granted US$30 million for preliminary studies.[39][40]

Formulation

[edit]In April 2015, NASA invited the ESA to submit concepts for an additional probe to fly together with the Europa Clipper spacecraft, with a mass limit of 250 kg.[41] It could be a simple probe, an impactor,[42] or a lander.[43] An internal assessment at ESA considered whether there was interest and funds available,[44][45][46][47] opening a collaboration scheme similar to the very successful Cassini–Huygens approach.[47]

In May 2015, NASA chose nine instruments that would fly on board the orbiter, budgeted to cost about US$110 million over the next three years.[48] In June 2015, NASA approved the mission concept, allowing the orbiter to move to its formulation stage.[49] In January 2016, NASA approved the addition of a lander,[50][51] but this was canceled in 2017 because it was deemed too risky.[52] In May 2016, the Ocean Worlds Exploration Program was approved,[53] of which the Europa mission is part.[54]

In February 2017, the mission moved from Phase A to Phase B (the preliminary design phase).[55] On July 18, 2017, the House Space Subcommittee held hearings on the Europa Clipper as a scheduled Large Strategic Science Missions class, and to discuss a possible follow up mission simply known as the Europa Lander.[56] Phase B continued into 2019.[55] In addition, subsystem vendors were selected, as well as prototype hardware elements for the science instruments. Spacecraft sub-assemblies were built and tested as well.[55]

Fabrication and assembly

[edit]

On August 19, 2019, the Europa Clipper proceeded to Phase C: final design and fabrication.[57]

On March 3, 2022, the spacecraft moved on to Phase D: assembly, testing, and launch.[58] On June 7, 2022, the main body of the spacecraft was completed.[59] By August 2022, the high-gain antenna had completed its major testing campaigns.[60]

By January 30, 2024, all of the science instruments were added to the spacecraft. The reason the instrument's electronics were aboard the spacecraft is because, while its antennas were added to the spacecraft's solar arrays at Kennedy Space Center later in the year, the electronics were not.[61] In March 2024, it was reported that the spacecraft underwent successful testing and was on track for launch later in the year.[62] In May 2024, the spacecraft arrived at Kennedy Space Center for final launch preparations.[63] In September 2024, final pre-launch review was successfully completed, clearing the way for launch.[64] In early October 2024, due to the incoming Hurricane Milton, the spacecraft was placed in secure storage for safekeeping until the hurricane passed.[65]

Launch

[edit]In July 2024, the spacecraft faced concerns of delay and missing the launch window because of a discovery in June 2024 that its components were not as radiation-hardened as previously believed.[66] However, over the summer, intensive re-testing of the transistor components in question found that they would likely be annealed enough to 'self-heal'.[67][68] In September 2024, Europa Clipper was approved for a launch window opening on October 10, 2024;[67][69][68] however, on October 6, 2024, NASA announced that it would be standing down from the October 10 launch due to Hurricane Milton. Europa Clipper was finally launched on October 14, 2024.[65]

End of mission planning

[edit]The probe is scheduled to be crashed into Jupiter, Ganymede, or Callisto, to prevent it from crashing into Europa. In June 2022, lead project scientist Robert Pappalardo revealed that mission planners for Europa Clipper were considering disposing of the probe by crashing it into the surface of Ganymede in case an extended mission was not approved early in the main science phase. He noted that an impact would help the ESA's Juice mission collect more information about Ganymede's surface chemistry.[70][71] In a 2024 paper, Pappalardo said the mission would last four years in Jupiter orbit, and that the disposal was targeted for September 3, 2034, if NASA did not approve a mission extension.[72]

Objectives

[edit]

The goals of Europa Clipper are to explore Europa, investigate its habitability and aid in the selection of a landing site for the proposed Europa Lander.[51][73] This exploration is focused on understanding the three main requirements for life: liquid water, chemistry, and energy.[74] Specifically, the objectives are to study:[31]

- Ice shell and ocean: Confirm the existence and characterize the nature of water within or beneath the ice, and study processes of surface-ice-ocean exchange.

- Composition: Distribution and chemistry of key compounds and the links to ocean composition.

- Geology: Characteristics and formation of surface features, including sites of recent or current activity.

The spacecraft carries scientific instruments which will be used to analyze the potential presence of geothermal activity and the moon's induced magnetic field; which in turn will provide an indication to the presence of saline rich subsurface ocean(s).[75][76]

Strategy

[edit]

Because Europa lies well within the harsh radiation fields surrounding Jupiter, even a radiation-hardened spacecraft in near orbit would be functional for just a few months.[28] Most instruments can gather data far faster than the communications system can transmit it to Earth due to the limited number of antennas available on Earth to receive the scientific data.[28] Therefore, another key limiting factor on science for a Europa orbiter is the time available to return data to Earth. In contrast, the amount of time during which the instruments can make close-up observations is less important.[28]

Studies by scientists from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory show that by performing several flybys with many months to return data, the Europa Clipper concept will enable a US$2 billion mission to conduct the most crucial measurements of the canceled US$4.3 billion Jupiter Europa Orbiter concept.[28] Between each of the flybys, the spacecraft will have seven to ten days to transmit data stored during each brief encounter. That will let the spacecraft have up to a year of time to transmit its data compared to just 30 days for an orbiter. The result will be almost three times as much data returned to Earth, while reducing exposure to radiation.[28] Europa Clipper will not orbit Europa, but will instead orbit Jupiter and conduct 49 flybys of Europa, each at altitudes ranging from 25 to 2,700 km (16 to 1,678 mi) during its 3.5-year mission.[18][2][77] A key feature of the mission concept is that Europa Clipper would use gravity assists from Europa, Ganymede and Callisto to change its trajectory, allowing the spacecraft to return to a different close approach point with each flyby.[2] Each flyby would cover a different sector of Europa to achieve a medium-quality global topographic survey, including ice thickness.[78] Europa Clipper could conceivably fly by at low altitude through the plumes of water vapor erupting from the moon's ice crust, thus sampling its subsurface ocean without having to land on the surface and drill through the ice.[33][34]

The spacecraft is expected to receive a total ionizing dose of 2.8 megarads (28 kGy) during the mission. Shielding from Jupiter's harsh radiation belt will be provided by a radiation vault with 9.2 mm (0.36 in) thick aluminum alloy walls, which enclose the spacecraft electronics.[79] To maximize the effectiveness of this shielding, the electronics are also nested in the core of the spacecraft for additional radiation protection.[78]

Design and construction

[edit]

Europa Clipper is a NASA Planetary Science Division mission, designated a Large Strategic Science Mission, and funded under the Planetary Missions Program Office's Solar System Exploration program as its second flight.[56][80] It is also supported by the new Ocean Worlds Exploration Program.[54]

The spacecraft bus is a 5-meter-long combination of a 150-cm-wide aluminum cylindrical propulsion module and a rectangular box.[5] The electronic components are protected from the intense radiation by a 150-kilogram titanium, zinc and aluminum shielded vault in the box.[6][78]

Power

[edit]Both radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) and photovoltaic power sources were assessed to power the orbiter.[81] Although solar power is only 4% as intense at Jupiter as it is in Earth's orbit, powering a Jupiter orbital spacecraft by solar panels was demonstrated by the Juno mission. The alternative to solar panels was a multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG), fueled with plutonium-238.[2][78] The power source has already been demonstrated in the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission. Five units were available, with one reserved for the Mars 2020 rover mission and another as backup. In September 2013, it was decided that the solar array was the less expensive option to power the spacecraft, and on October 3, 2014, it was announced that solar panels were chosen to power Europa Clipper. The mission's designers determined that solar power was both cheaper than plutonium and practical to use on the spacecraft.[81] Despite the increased weight of solar panels compared to plutonium-powered generators, the vehicle's mass had been projected to still be within acceptable launch limits.[82]

Each panel has a surface area of 18 m2 (190 sq ft) and produces 150 watts continuously when pointed towards the Sun while orbiting Jupiter.[83] While in Europa's shadow, batteries will enable the spacecraft to continue gathering data. However, ionizing radiation can damage solar panels. The Europa Clipper's orbit will pass through Jupiter's intense magnetosphere, which is expected to gradually degrade the solar panels as the mission progresses.[78] The solar panels were provided by Airbus Defence and Space, Netherlands.[84]

Propulsion

[edit]The propulsion subsystem was built by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. It is part of the Propulsion Module,[5] delivered by Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. It is 3 metres (10 ft) tall, 1.5 metres (5 ft) in diameter and comprises about two-thirds of the spacecraft's main body. The propulsion subsystem carries nearly 2,700 kilograms (6,000 lb) of monomethyl hydrazine and dinitrogen tetroxide propellant, 50% to 60% of which will be used for the 6 to 8-hour Jupiter orbit insertion burn. The spacecraft has a total of 24 rocket engines rated at 27.5 N (6.2 lbf) thrust for attitude control and propulsion.[5]

Communication

[edit]

The spacecraft includes a suite of antennas for communication and scientific measurements. Chief among them is the high-gain antenna (HGA), which has a 3.1-meter (10-foot) diameter and is capable of both uplink and downlink communications over multiple frequency bands. The HGA operates on X-band frequencies of 7.2 GHz (uplink) and 8.4 GHz (downlink), as well as a Ka-band frequency of 32 GHz, approximately 12 times higher than typical cellular communications.[60]

The communication system includes additional antennas such as low-gain antennas (LGAs), medium-gain antennas (MGAs), and fan-beam antennas (FBAs), which are used for different mission phases depending on orientation and distance from Earth.[85]

The Ka-band is primarily used for high-rate data return, enabling faster transmission of scientific data. Data rates vary depending on antenna alignment, frequency, and ground station availability. Downlink data rates via X-band can reach approximately 16 kilobits per second, while Ka-band transmissions can reach up to 500 kilobits per second under optimal conditions.[72] Uplink rates for command transmission are typically around 2 kilobits per second.

The antenna system supports not only communications but also radio science and gravity science experiments. Using coherent two-way X-band Doppler tracking and radio occultation techniques, researchers will study Europa's internal structure, ice shell thickness, ocean characteristics, and gravity field. Small variations in the spacecraft's velocity—detected via Doppler shifts—will help scientists determine the moon's mass distribution and potential subsurface ocean.[86]

The HGA was designed and developed under the leadership of Matt Bray at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and underwent rigorous testing at Langley Research Center and Goddard Space Flight Center in 2022, including beam pattern, thermal vacuum, and vibration testing to ensure precision and reliability.[60]

Scientific equipment

[edit]The Europa Clipper mission is equipped with nine scientific instruments.[87] The nine science instruments for the orbiter, announced in May 2015, have a planned total mass of 82 kg (181 lb).[needs update][88]

Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS)

[edit]The Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System will provide high spatial resolution as well as multi-spectral imaging of the surface of Europa in the mid to far infrared bands to help detect heat which would suggest geologically active sites and areas, such as potential vents erupting plumes of water into space.[89]

The principal investigator is Philip Christensen of Arizona State University. This instrument is derived from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) on the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter, also developed by Philip Christensen.[90]

Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE)

[edit]

The Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa is an imaging near infrared spectrometer to probe the surface composition of Europa, identifying and mapping the distributions of organics (including amino acids and tholins[91][92]), salts, acid hydrates, water ice phases, and other materials.[92][93]

The principal investigator is Diana Blaney of Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the instrument was built in collaboration with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL).

Europa Imaging System (EIS)

[edit]The Europa Imaging System consists of visible spectrum cameras to map Europa's surface and study smaller areas in high resolution, as low as 0.5 m (20 in) per pixel. It consists of two cameras, both of which use 2048x4096 pixel CMOS detectors:[94][95]

- The Wide-angle Camera (WAC) has a field of view of 48° by 24° and a resolution of 11 m (36 ft) from a 50 km (31 mi) altitude. Optically the WAC uses 8 lens refractive optics with an 8 mm aperture and a 46 mm focal length which give it a f-number of f/5.75.[95] The WAC will obtain stereo imagery swaths throughout the mission.

- The Narrow-angle Camera (NAC) has a 2.3° by 1.2° field of view, giving it a resolution of 0.5 m (20 in) per pixel from a 50 km (31 mi) altitude. Optically the NAC uses a Ritchey Chrétien Cassegrain telescope with a 152 mm aperture and a 1000 mm focal length which give it a f-number of f/6.58.[95] The NAC is mounted on a 2-axis gimbal, allowing it to point at specific targets regardless of the main spacecraft's orientation. This will allow for mapping of >95% of Europa's surface at a resolution of ≤50 m (160 ft) per pixel. For reference, only around 14% of Europa's surface has previously been mapped at a resolution of ≤500 m (1,600 ft) per pixel.

The principal investigator is Elizabeth Turtle of the Applied Physics Laboratory.

Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (Europa-UVS)

[edit]The Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph instrument will be able to detect small erupting plumes, and will provide valuable data about the composition and dynamics of the moon's exosphere.[76]

The principal investigator is Kurt Retherford of Southwest Research Institute. Retherford was previously a member of the group that discovered plumes erupting from Europa while using the Hubble Space Telescope in the UV spectrum.[96]

Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON)

[edit]The Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON)[97][98] is a dual-frequency ice penetrating radar (9 and 60 MHz) instrument that is designed to sound Europa's ice crust from the near-surface to the ocean, revealing the hidden structure of Europa's ice shell and potential water pockets within. REASON will probe the exosphere, surface and near-surface and the full depth of the ice shell to the ice-ocean interface up to 30 km.[92][97]

The principal investigator is Donald Blankenship of the University of Texas at Austin.[99] This instrument was built by Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Europa Clipper Magnetometer (ECM)

[edit]The Europa Clipper Magnetometer (ECM) will be used to analyze the magnetic field around Europa. The instrument consists of three flux gates placed along an 8.5 metres (28 feet) boom, which were stowed during launch and deployed afterwards.[100] The magnetic field of Jupiter is thought to induce electric current in a salty ocean beneath Europa's ice, which in turn leads Europa to produce its own magnetic field, therefore by studying the strength and orientation of Europa's magnetic field over multiple flybys, scientists hope to be able to confirm the existence of Europa's subsurface ocean, as well as characterize the thickness of its icy crust and estimate the water's depth and salinity.[75]

The instrument team leader is Margaret Kivelson, University of Michigan.[101]

ECM replaced the proposed Interior Characterization of Europa using Magnetometry (ICEMAG) instrument, which was canceled due to cost overruns.[102] ECM is a simpler and cheaper magnetometer than ICEMAG would have been.[103]

Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS)

[edit]

The Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS) measures the plasma surrounding Europa to characterize the magnetic fields generated by plasma currents. These plasma currents mask the magnetic induction response of Europa's subsurface ocean. In conjunction with a magnetometer, it is key to determining Europa's ice shell thickness, ocean depth, and salinity. PIMS will also probe the mechanisms responsible for weathering and releasing material from Europa's surface into the atmosphere and ionosphere and understanding how Europa influences its local space environment and Jupiter's magnetosphere.[104][105]

The principal investigator is Joseph Westlake of the Applied Physics Laboratory.

Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration (MASPEX)

[edit]The Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration (MASPEX) will determine the composition of the surface and subsurface ocean by measuring Europa's extremely tenuous atmosphere and any surface materials ejected into space.[106][107]

Jack Waite, who led development of MASPEX, was also Science Team Lead of the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) on the Cassini spacecraft. The principal investigator is Jim Burch of Southwest Research Institute, who was previously the leader of the Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission.

Surface Dust Analyzer (SUDA)

[edit]

The SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA)[13] is a mass spectrometer that will measure the composition of small solid particles ejected from Europa, providing the opportunity to directly sample the surface and potential plumes on low-altitude flybys. The instrument is capable of identifying traces of organic and inorganic compounds in the ice of ejecta,[108] and is sensitive enough to detect signatures of life even if the sample contains less than a single bacterial cell in a collected ice grain.[109]

The principal investigator is Sascha Kempf of the University of Colorado Boulder.

Gravity & Radio Science

[edit]Although it was designed primarily for communications, the high-gain radio antenna will be used to perform additional radio observations and investigate Europa's gravitational field, acting as a radio science subsystem. Measuring the Doppler shift in the radio signals between the spacecraft and Earth will allow the spacecraft's motion to be determined in detail. As the spacecraft performs each of its 45 Europa flybys, its trajectory will be altered by the moon's gravitational field. The Doppler data will be used to determine the higher order coefficients of that gravity field, to determine the moon's interior structure, and to examine how Europa is deformed by tidal forces.[85]

The instrument team leader is Erwan Mazarico of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.[86]

Launch and trajectory

[edit]

Launch preparations

[edit]Congress had originally mandated that Europa Clipper be launched on NASA's Space Launch System (SLS) super heavy-lift launch vehicle, but NASA had requested that other vehicles be allowed to launch the spacecraft due to a foreseen lack of available SLS vehicles.[110] The United States Congress's 2021 omnibus spending bill directed the NASA Administrator to conduct a full and open competition to select a commercial launch vehicle if the conditions to launch the probe on a SLS rocket cannot be met.[111]

On January 25, 2021, NASA's Planetary Missions Program Office formally directed the mission team to "immediately cease efforts to maintain SLS compatibility" and move forward with a commercial launch vehicle.[15]

On February 10, 2021, it was announced that the mission would use a 5.5-year trajectory to the Jovian system, with gravity-assist maneuvers involving Mars (March 1, 2025) and Earth (December 3, 2026). Launch was targeted for a 21-day period between October 10 and 30, 2024, giving an arrival date in April 2030, and backup launch dates were identified in 2025 and 2026.[15]

The SLS option would have entailed a direct trajectory to Jupiter taking less than three years.[50][51][2] One alternative to the direct trajectory was identified as using a commercial rocket, with a longer 6-year cruise time involving gravity assist maneuvers at Venus, Earth and/or Mars. Additionally, a launch on a Delta IV Heavy with a gravity assist at Venus was considered.[112]

In July 2021 the decision was announced to launch on a Falcon Heavy rocket, in fully expendable configuration.[8] Three reasons were given: reasonable launch cost (ca. $178 million), questionable SLS availability, and possible damage to the payload due to strong vibrations caused by the solid boosters attached to the SLS launcher.[112] The move to Falcon Heavy saved an estimated US$2 billion in launch costs alone.[113][112] NASA was not sure an SLS would be available for the mission since the Artemis program would use SLS rockets extensively, and the SLS's use of solid rocket boosters (SRBs) generates more vibrations in the payload than a launcher that does not use SRBs. The cost to redesign Europa Clipper for the SLS vibratory environment was estimated at US$1 billion.

Launch

[edit]Europa Clipper was originally scheduled to launch on October 10, two days after a Falcon 9 launched the ESA's Hera to 65803 Didymos from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on a similar interplanetary trajectory. However, this launch attempt was scrubbed due to Hurricane Milton making landfall in Florida the previous day, resulting in the launch being finalized for several days later.[114] Europa Clipper was launched on October 14, 2024, at 12:06 p.m. EDT from Launch Complex 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center on a Falcon Heavy.[115] The rocket's boosters and first stage were both expended as a result of the spacecraft's mass and trajectory; the boosters were previously flown five times (including on the launch of Psyche for NASA and an X-37B for the United States Space Force), while the center stage was only flown for this mission.

Transit and observation

[edit]The trajectory of Europa Clipper started with a gravity assist from Mars on March 1, 2025,[9] causing the probe to slow down a little (speed reduced by 2 kilometers per second) and modifying its orbit around the Sun such that it will allow the spacecraft to fly by Earth on December 3, 2026, gaining additional speed.[116][10] The probe will then arc (reach aphelion) beyond Jupiter's orbit on October 4, 2029[117] before slowly falling into Jupiter's gravity well and executing its orbital insertion burn in April 2030.[118]

As of 2014[update], the trajectory in the Jupiter system is planned as follows.[needs update] After entry into the Jupiter system, Europa Clipper will perform a flyby of Ganymede at an altitude of 500 km (310 mi), which will reduce the spacecraft velocity by ~400 m/s (890 mph). This will be followed by firing the main engine at a distance of 11 Rj (Jovian radii), to provide a further ~840 m/s (1,900 mph) of delta-V, sufficient to insert the spacecraft into a 202-day orbit around Jupiter. Once the spacecraft reaches the apoapsis of that initial orbit, it will perform another engine burn to provide a ~122 m/s (270 mph) periapsis raise maneuver (PRM).[119][needs update]

The spacecraft's cruise and science phases will overlap with the ESA's Juice spacecraft, which was launched in April 2023 and will arrive at Jupiter in July 2031. Europa Clipper is due to arrive at Jupiter 15 months prior to Juice, despite a launch date planned 18 months later, owing to a more powerful launch vehicle and a faster flight plan with fewer gravity assists.

Public outreach

[edit]To raise public awareness of the Europa Clipper mission, NASA undertook a "Message in a Bottle" campaign, i.e. an actual "Send Your Name to Europa" campaign on June 1, 2023, through which people around the world were invited to send their names as signatories to a poem called "In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa" written by the U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón, for the 2.9-billion-kilometer (1.8-billion mi) voyage to Jupiter. The poem describes the connections between Earth and Europa.[120]

The poem is engraved on Europa Clipper inside a tantalum metal plate, about 7 by 11 inches (18 by 28 centimeters), that seals an opening into the vault. The inward-facing side of the metal plate is engraved with the poem in the poet's own handwriting. The public participants' names are etched onto a microchip attached to the plate, within an artwork of a wine bottle surrounded by the four Galilean moons.[121] After registering their names, participants received a digital ticket with details of the mission's launch and destination. According to NASA, 2,620,861 people signed their names to Europa Clipper's Message in a Bottle, most of whom were from the United States.[122] Other elements etched on the inwards side together with the poem and names are the Drake equation, representations of the spectral lines of a hydrogen atom and the hydroxyl radical, together known as the water hole, and a portrait of planetary scientist Ron Greeley.[123] The outward-facing panel features art that highlights Earth's connection to Europa. Linguists collected recordings of the word "water" spoken in 103 languages, from families of languages around the world. The audio files were converted into waveforms and etched into the plate. The waveforms radiate out from a symbol representing the American Sign Language sign for "water".[124] The research organization METI International gathered the audio files for the words for "water", and its president Douglas Vakoch designed the water hole component of the message.[125][126]

-

The outside of the Europa Clipper commemorative plate features waveforms that are visual representations of the sound waves formed by the word "water" in 103 languages

-

The inside of a commemorative plate mounted on NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft features U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón's handwritten "In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa" (blurred for copyright reasons)

See also

[edit]- Europa Orbiter – Cancelled NASA orbiter mission to Europa

- Europa Jupiter System Mission – Laplace – Canceled orbiter mission concept to Jupiter

- Exploration of Jupiter – Overview of the exploration of the planet Jupiter and its moons

- Galileo (spacecraft) – First NASA mission to orbit Jupiter (1989–2003)

- Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer – European mission to study Jupiter and its moons since 2023

- Laplace-P – Proposed Russian spacecraft to study the Jovian moon system and land on Ganymede

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Leone, Dan (July 22, 2013). "NASA's Europa Mission Concept Progresses on the Back Burner". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Phillips, Cynthia B.; Pappalardo, Robert T. (May 20, 2014). "Europa Clipper Mission Concept". Eos Transactions. 95 (20). Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union: 165–167. Bibcode:2014EOSTr..95..165P. doi:10.1002/2014EO200002.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (January 29, 2021). "NASA seeks input on Europa Clipper launch options". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Barry; Kastner, Jason (March 2018). "Weigh Your Options Carefully" (PDF). The Sextant – Europa Clipper Newsletter. Vol. 2, no. 1. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d Rehm, Jeremy (June 7, 2022). "Johns Hopkins APL Delivers Propulsion Module for NASA Mission to Europa". JHUAPL. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Europa Clipper Mission Overview". NASA. June 25, 2025. Retrieved October 13, 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Goldstein, Barry; Pappalardo, Robert (February 19, 2015). "Europa Clipper Update" (PDF). Outer Planets Assessment Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Potter, Sean (July 23, 2021). "NASA Awards Launch Services Contract for the Europa Clipper Mission" (Press release). NASA. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Eyes on the Solar System - NASA/JPL".

- ^ a b c "Eyes on the Solar System - NASA/JPL".

- ^ "Eyes on the Solar System - NASA/JPL".

- ^ "All Systems Go for NASA's Mission to Jupiter Moon Europa" (Press release). NASA. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Thompson, Jay R. (2022). "Instruments". Europa Clipper. NASA. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Europa Clipper launches aboard SpaceX rocket, bound for Jupiter's icy ocean moon". Los Angeles Times. October 14, 2024. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (February 10, 2021). "NASA to use commercial launch vehicle for Europa Clipper". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Clark, Stuart (March 5, 2023). "'It's like finding needles in a haystack': the mission to discover if Jupiter's moons support life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ King, Lucinda; Conversation, The. "If life exists on Jupiter's moon Europa, scientists might soon be able to detect it". phys.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Europa Clipper - NASA Science". NASA. December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "How our vision of Europa's habitability is changing". April 19, 2024. Archived from the original on April 24, 2024. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ "In Depth". NASA's Europa Clipper. December 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ Dyches, Preston (March 9, 2017). "NASA Mission Named 'Europa Clipper'". JPL (NASA). Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Edwards, Bradley C.; Chyba, Christopher F.; Abshire, James B.; Burns, Joseph A.; Geissler, Paul; Konopliv, Alex S.; Malin, Michael C.; Ostro, Steven J.; Rhodes, Charley; Rudiger, Chuck; Shao, Xuan-Min; Smith, David E.; Squyres, Steven W.; Thomas, Peter C.; Uphoff, Chauncey W.; Walberg, Gerald D.; Werner, Charles L.; Yoder, Charles F.; Zuber, Maria T. (July 11, 1997). The Europa Ocean Discovery mission. Proc. SPIE 3111, Instruments, Methods, and Missions for the Investigation of Extraterrestrial Microorganisms. doi:10.1117/12.278778.

- ^ a b Meltzer, Michael (2007). Mission to Jupiter: A History of the Galileo Project (PDF). The NASA History Series. NASA. OCLC 124150579. SP-4231. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Dreier, Casey (December 12, 2013). "Europa: No Longer a 'Should', But a 'Must'". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Irwin, Louis N. (2001). "Alternative Energy Sources Could Support Life on Europa" (PDF). Departments of Geological and Biological Sciences. University of Texas at El Paso. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2006.

- ^ a b c Zabarenko, Deborah (March 7, 2011). "Lean U.S. missions to Mars, Jupiter moon recommended". Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Project Prometheus final report" (PDF). 2005. p. 178. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f Kane, Van (August 26, 2014). "Europa: How Less Can Be More". Planetary Society. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ Jeff Foust (August 22, 2019). "Europa Clipper passes key review". Space News. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ NASA Europa Mission Could Potentially Spot Signs of Alien Life Archived January 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Mike Wall, Space.com, October 26, 2019

- ^ a b Pappalardo, Robert; Cooke, Brian; Goldstein, Barry; Prockter, Louise; Senske, Dave; Magner, Tom (July 2013). "The Europa Clipper" (PDF). OPAG Update. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "Destination: Europa". Europa SETI. March 29, 2013. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Wall, Mike (March 5, 2014). "NASA Eyes Ambitious Mission to Jupiter's Icy Moon Europa by 2025". Space.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (March 14, 2014). "Economics, water plumes to drive Europa mission study". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ Zezima, Katie (May 8, 2014). "House gives NASA more money to explore planets". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Morin, Monte (May 8, 2014). "US$17.9-billion funding plan for NASA would boost planetary science". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Nola Taylor Redd (November 5, 2014). "To Europa! Mission to Jupiter's Moon Gains Support in Congress". Space.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Dreier, Casey (February 3, 2015). "It's Official: We're On the Way to Europa". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Kane, Van (February 3, 2015). "2016 Budget: Great Policy Document and A Much Better Budget". Future Planetary Exploration. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (March 10, 2015). "Europa Multiple Flyby Mission concept team aims for launch in 2022". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Di Benedetto, Mauro; Imperia, Luigi; Durantea, Daniele; Dougherty, Michele; Iessa, Luciano (September 26–30, 2016). Augmenting NASA Europa Clipper by a small probe: Europa Tomography Probe (ETP) mission concept. 67th International Astronautical Congress (IAC).

- ^ Akon – A Penetrator for Europa Archived August 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Geraint Jones, Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 18, EGU2016-16887, 2016, EGU General Assembly 2016

- ^ Clark, Stephen (April 10, 2015). "NASA invites ESA to build Europa piggyback probe". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (April 19, 2016). "European scientists set eyes on ice moon Europa". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- ^ Blanc, Michel; Jones, Geraint H.; Prieto-Ballesteros, Olga; Sterken, Veerle J. (2016). "The Europa initiative for ESA's cosmic vision: a potential European contribution to NASA's Europa mission" (PDF). Geophysical Research Abstracts. 18: EPSC2016-16378. Bibcode:2016EGUGA..1816378B. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Joint Europa Mission: ESA and NASA together towards Jupiter icy moon". ResearchItaly - Joint Europa Mission: ESA and NASA together towards Jupiter icy moon. Research Italy. May 16, 2017. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Joint Europa Mission (JEM): A multi-scale study of Europa to characterize its habitability and search for life Archived August 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Michel Blanc, Olga Prieto Ballesteros, Nicolas Andre, and John F. Cooper, Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 19, EGU2017-12931, 2017, EGU General Assembly 2017

- ^ Klotz, Irene (May 26, 2015). "NASA's Europa Mission Will Look for Life's Ingredients". Gazette Herald. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (June 20, 2015). "NASA's Europa Mission Approved for Next Development Stage". Space.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Kornfeld, Laurel (January 4, 2016). "Additional US$1.3 billion for NASA to fund next Mars rover, Europa mission". The Space Reporter. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Kane, Van (January 5, 2016). "A Lander for NASA's Europa Mission". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ "NASA Receives Science Report on Europa Lander Concept". NASA. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA'S FY2017 Budget Request – Status at the End of the 114th Congress" (PDF). spacepolicyonline.com. December 28, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "NASA'S FY2016 Budget Request – Overview" (PDF). spacepolicyonline.com. May 27, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Greicius, Tony (February 21, 2017). "NASA's Europa Flyby Mission Moves into Design Phase". NASA. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Wolfe, Alexis; McDonald, Lisa (July 21, 2017). "Balance of NASA Planetary Science Missions Explored at Hearing". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ McCartney, Gretchen; Johnson, Alana (August 19, 2019). "Mission to Jupiter's Icy Moon Confirmed". NASA. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ McCartney, Gretchen; Johnson, Alana (March 3, 2022). "NASA Begins Assembly of Europa Clipper Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ McCartney, Gretchen; Johnson, Alana (June 7, 2022). "NASA's Europa Clipper Mission Completes Main Body of the Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Europa Clipper High-Gain Antenna Undergoes Precision Testing at NASA Langley". NASA. August 4, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ McCartney, Gretchen; Fox, Karen; Johnson, Alana (January 30, 2024). "Poised for Science: NASA's Europa Clipper Instruments Are All Aboard". NASA. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Europa Clipper Survives and Thrives in 'Outer Space' on Earth – NASA". March 27, 2024. Archived from the original on March 28, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "NASA's Europa Clipper Makes Cross-Country Flight to Florida". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Archived from the original on May 25, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 9, 2024). "Europa Clipper passes pre-launch review". SpaceNews. Retrieved September 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "SpaceX, NASA stand down from Oct. 10 Europa Clipper launch due to Hurricane Milton". Space.com. October 7, 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (July 12, 2024). "NASA's flagship mission to Europa has a problem: Vulnerability to radiation". Ars Technica. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Brown, David W. (September 17, 2024). "A $5 Billion NASA Mission Looked Doomed. Could Engineers Save It?". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Harwood, William (September 9, 2024). "NASA clears $5 billion Jupiter mission for launch after review of suspect transistors". CBS News. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ "NASA clears Europa Clipper mission for Oct. 10 launch despite Jupiter radiation worries". Space.com. September 4, 2024.

- ^ "14 OPAG June 2022 Day 2 Bob Pappalardo Jordan Evans (unlisted)". July 19, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Waldek, Stefanie (June 29, 2022). "NASA's Europa Clipper may crash into Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, at mission's end". Space.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Pappalardo, Robert T.; Buratti, Bonnie J.; Korth, Haje; Senske, David A.; et al. (May 23, 2024). "Science Overview of the Europa Clipper Mission". Space Science Reviews. 220 (4) 40. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. Bibcode:2024SSRv..220...40P. doi:10.1007/s11214-024-01070-5. hdl:1721.1/155077. ISSN 0038-6308.

- ^ Pappalardo, Robert T.; Vance, S.; Bagenal, F.; Bills, B.G.; Blaney, D.L.; Blankenship, D.D.; Brinckerhoff, W.B.; Connerney, J.E.P.; Hand, K.P.; Hoehler, T.M.; Leisner, J.S.; Kurth, W.S.; McGrath, M.A.; Mellon, M.T.; Moore, J.M.; Patterson, G.W.; Prockter, L.M.; Senske, D.A.; Schmidt, B.E.; Shock, E.L.; Smith, D.E.; Soderlund, K.M. (2013). "Science Potential from a Europa Lander" (PDF). Astrobiology. 13 (8): 740–773. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13..740P. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1003. hdl:1721.1/81431. PMID 23924246. S2CID 10522270. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ Bayer, Todd; Buffington, Brent; Castet, Jean-Francois; Jackson, Maddalena; Lee, Gene; Lewis, Kari; Kastner, Jason; Schimmels, Kathy; Kirby, Karen (March 4, 2017). "Europa mission update: Beyond payload selection". 2017 IEEE Aerospace Conference. Big Sky, Montana. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1109/AERO.2017.7943832. ISBN 978-1-5090-1613-6.

- ^ a b "ECM: How We'll Use It". NASA. December 2017. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Retherford, K. D.; Gladstone, R.; Greathouse, T. K.; Steffl, A.; Davis, M. W.; Feldman, P. D.; McGrath, M. A.; Roth, L.; Saur, J.; Spencer, J. R.; Stern, S. A.; Pope, S.; Freeman, M. A.; Persyn, S. C.; Araujo, M. F.; Cortinas, S. C.; Monreal, R. M.; Persson, K. B.; Trantham, B. J.; Versteeg, M. H.; Walther, B. C. (2015). "The Ultraviolet Spectrograph on the Europa Mission (Europa-UVS)". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2015. Bibcode:2015AGUFM.P13E..02R.

- ^ "Europa Clipper". NASA (JPL). Archived from the original on March 23, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e Kane, Van (May 26, 2013). "Europa Clipper Update". Future Planetary Exploration. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "Meet Europa Clipper". NASA. April 29, 2025. Archived from the original on April 30, 2025. Retrieved October 6, 2025.

- ^ "Solar System Exploration Missions List". Planetary Missions Program Office (PMPO). NASA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b A. Eremenko et al., "Europa Clipper spacecraft configuration evolution", 2014 IEEE Aerospace Conference, pp. 1–13, Big Sky, MT, March 1–8, 2014

- ^ Foust, Jeff (October 8, 2014). "Europa Clipper Opts for Solar Power over Nuclear". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Dreier, Casey (September 5, 2013). "NASA's Europa Mission Concept Rejects ASRGs – May Use Solar Panels at Jupiter Instead". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ "Spacecraft Highlights" (PDF). The Sextant – Europa Clipper Newsletter. Vol. 2, no. 1. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. March 2018. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Mazarico, Erwan; et al. (June 2023). "The Europa Clipper Gravity and Radio Science Investigation". Space Science Reviews. 219 (4) 30. Bibcode:2023SSRv..219...30M. doi:10.1007/s11214-023-00972-0. hdl:11585/939921.

- ^ a b "Gravity / Radio Science Instruments". NASA. April 29, 2025. Archived from the original on April 30, 2025. Retrieved October 6, 2025.

- ^ Becker, T. M.; Zolotov, M. Y.; Gudipati, M. S.; Soderblom, J. M.; McGrath, M. A.; Henderson, B. L.; Hedman, M. M.; Choukroun, M.; Clark, R. N.; Chivers, C.; Wolfenbarger, N. S.; Glein, C. R.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Mousis, O.; Scanlan, K. M.; et al. (August 2024). "Exploring the Composition of Europa with the Upcoming Europa Clipper Mission". Space Science Reviews. 220 (5): 49. Bibcode:2024SSRv..220...49B. doi:10.1007/s11214-024-01069-y. hdl:1721.1/155425. ISSN 1572-9672.

- ^ "NASA's Europa Mission Begins with Selection of Science Instruments". NASA (JPL). May 26, 2015. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "OPAG Meeting" (PDF). lpi.usra.edu.

- ^ "E-THEMIS | Christensen Research Group". Christensen Research Group. Arizona State University. April 25, 2019. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ MISE: A Search for Organics on Europa Archived November 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Whalen, Kelly; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Blaney, Diana L.; American Astronomical Society, AAS Meeting No. 229, id.138.04, January 2017

- ^ a b c "Europa Mission to Probe Magnetic Field and Chemistry". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. May 27, 2015. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Blaney, Diana L. (2010). "Europa Composition Using Visible to Short Wavelength Infrared Spectroscopy". JPL. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 42, #26.04; Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, Vol. 42, p. 1025.

- ^ Turtle, Elizabeth; Mcewen, Alfred; Collins, G.; Fletcher, L.; Hansen, C.; Hayes, A.; Hurford, T.; Kirk, R.; Mlinar, A.C. "THE EUROPA IMAGING SYSTEM (EIS): HIGH RESOLUTION IMAGING AND TOPOGRAPHY TO INVESTIGATE EUROPA'S GEOLOGY, ICE SHELL, AND POTENTIAL FOR CURRENT ACTIVITY" (PDF). Universities Space Research Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Europa Clipper Instrument Summaries" (PDF). December 2017.

- ^ Roth, Lorenz (2014). "Transient Water Vapor at Europa's South Pole". Science. 343 (171): 171–174. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..171R. doi:10.1126/science.1247051. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 24336567. S2CID 27428538.

- ^ a b "Radar Techniques Used in Antarctica Will Scour Europa for Life-Supporting Environments". University of Texas Austin. June 1, 2015. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Grima, Cyril; Schroeder, Dustin; Blakenship, Donald D.; Young, Duncan A. (November 15, 2014). "Planetary landing-zone reconnaissance using ice-penetrating radar data: Concept validation in Antarctica". Planetary and Space Science. 103: 191–204. Bibcode:2014P&SS..103..191G. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2014.07.018.

- ^ Blankenship, Donald D.; Moussessian, Alina; Chapin, Elaine; Young, Duncan A.; Patterson, G.; Plaut, Jeffrey J.; Freedman, Adam P.; Schroeder, Dustin M.; Grima, Cyril; Steinbrügge, Gregor; Soderlund, Krista M.; Ray, Trina; Richter, Thomas G.; Jones-Wilson, Laura; Wolfenbarger, Natalie S. (June 2024). "Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-Surface (REASON)". Space Science Reviews. 220 (5): 51. Bibcode:2024SSRv..220...51B. doi:10.1007/s11214-024-01072-3. ISSN 1572-9672. PMC 11211191. PMID 38948073.

- ^ "ECM Instruments – NASA's Europa Clipper". NASA. December 2017. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Kivelson, Margaret G.; et al. (September 2023). "The Europa Clipper Magnetometer". Space Science Reviews. 219 (6): 48. Bibcode:2023SSRv..219...48K. doi:10.1007/s11214-023-00989-5. hdl:1721.1/152366.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (March 6, 2019). "NASA to replace Europa Clipper instrument". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "NASA Seeks New Options for Science Instrument on Europa Clipper". NASA. March 5, 2019. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Westlake, Joseph; Rymer, A. M.; Kasper, J. C.; McNutt, R. L.; Smith, H. T.; Stevens, M. L.; Parker, C.; Case, A. W.; Ho, G. C.; Mitchell, D. G. (2014). The Influence of Magnetospheric Plasma on Magnetic Sounding of Europa's Interior Oceans (PDF). Workshop on the Habitability of Icy Worlds (2014). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Joseph, Westlake (December 14, 2015). "The Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS): Enabling Required Plasma Measurements for the Exploration of Europa". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2015. AGU: 13E–09. Bibcode:2015AGUFM.P13E..09W. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ "Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration / Europa (MASPEX)". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. NASA. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Waite, Jack; Lewis, W.; Kasprzak, W.; Anicich, V.; Block, B.; Cravens, T.; Fletcher, G.; Ip, W.; Luhmann, J (August 13, 1998). "THE CASSINI ION AND NEUTRAL MASS SPECTROMETER (INMS) INVESTIGATION" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. University of Arizona. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Kempf, Sascha; et al. (May 2012). "Linear high resolution dust mass spectrometer for a mission to the Galilean satellites". Planetary and Space Science. 65 (1): 10–20. Bibcode:2012P&SS...65...10K. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2011.12.019.

- ^ Klenner, Fabian; Bönigk, Janine; Napoleoni, Maryse; Hillier, Jon; Khawaja, Nozair; Olsson-Francis, Karen; Cable, Morgan L.; Malaska, Michael J.; Kempf, Sascha; Abel, Bernd; Postberg, Frank (2024). "How to identify cell material in a single ice grain emitted from Enceladus or Europa". Science Advances. 10 (12) eadl0849. Bibcode:2024SciA...10L.849K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl0849. PMC 10959401. PMID 38517965.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (July 10, 2020). "Cost growth prompts changes to Europa Clipper instruments". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (December 22, 2020). "NASA receives US$23.3 billion for 2021 fiscal year in Congress' omnibus spending bill". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Berger, Eric (July 23, 2021). "SpaceX to launch the Europa Clipper mission for a bargain price". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (July 25, 2021). "SpaceX Falcon Heavy to launch NASA ocean moon explorer, saving the US billions". Teslarati. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Harwood, William (October 6, 2024). "FAA clears European asteroid probe for launch, but stormy weather threatens delay". CBS News. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket launches NASA's Europa Clipper probe to explore icy Jupiter ocean moon". Space.com. October 14, 2024.

- ^ "NASA's Europa Clipper Uses Mars to Go the Distance". NASA. 2025. Retrieved May 18, 2025.

- ^ "Eyes on the Solar System: October 4, 2029". NASA. November 7, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2024. See also the point at which deldot equals 0 for Clipper relative to the Sun in the Horizons system app.

- ^ Manley, Scott (October 21, 2024). SpaceX Ditched an Entire Falcon Heavy To Launch NASA's Massive Probe To Europa! (YouTube video). YouTube. Scott Manley. Event occurs at 3 minutes 40 seconds. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ Buffington, Brent (August 5, 2014), Trajectory Design for the Europa Clipper Mission Concept (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2024, retrieved May 11, 2024

- ^ "In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa". NASA. May 2025. Archived from the original on May 2, 2025. Retrieved October 5, 2025.

- ^ "Europa Clipper Vault Plate". NASA. April 30, 2025. Archived from the original on September 13, 2025. Retrieved October 5, 2025.

- ^ "Participation Map | Message in a Bottle". NASA's Europa Clipper. Archived from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ "NASA Unveils Design for Message Heading to Jupiter's Moon Europa". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (March 9, 2024). "An Astrobiology Droid Asks And Answers 'How Many Ways Can You Say Water'?". Astrobiology. Archived from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Vakoch, Douglas (March 27, 2024). "See the messages NASA is sending to Jupiter's icy moon, Europa". New Scientist. Archived from the original on May 28, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Vakoch, Douglas (March 28, 2024). "NASA's mission to an ice-covered moon will contain a message between water worlds". The Conversation. Archived from the original on June 16, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Cochrane, Corey J.; et al. (June 2023). "Magnetic Field Modeling and Visualization of the Europa Clipper Spacecraft". Space Science Reviews. 219 (4): 34. Bibcode:2023SSRv..219...34C. doi:10.1007/s11214-023-00974-y. PMC 10220138. PMID 37251605.

- Pappalardo, Robert T.; et al. (June 2024). "Science Overview of the Europa Clipper Mission". Space Science Reviews. 220 (4): 40. Bibcode:2024SSRv..220...40P. doi:10.1007/s11214-024-01070-5. hdl:1721.1/155077. ISSN 0038-6308.

- Roberts, James H.; et al. (September 2023). "Exploring the Interior of Europa with the Europa Clipper". Space Science Reviews. 219 (6): 46. Bibcode:2023SSRv..219...46R. doi:10.1007/s11214-023-00990-y. PMC 10457249. PMID 37636325.

External links

[edit]Europa Clipper

View on GrokipediaMission overview

Primary objectives

The Europa Clipper mission's primary goal is to assess the habitability of Jupiter's moon Europa by determining whether environments beneath its icy surface could support life, focusing on the presence of liquid water, essential chemical compounds, and energy sources without attempting a landing.[9] This evaluation targets the three key ingredients for habitability: a vast subsurface ocean of liquid water, organic building blocks, and sustained energy from tidal interactions with Jupiter.[10] The mission's three main science objectives center on characterizing Europa's ice shell and underlying ocean, including their extent, composition, and interactions. It will investigate the thickness of the ice crust, potentially varying from a few to tens of kilometers, with estimates around 20-30 km, and how it exchanges material with the ocean below, such as through cryovolcanic processes or subsurface reservoirs.[4] Additionally, the spacecraft will examine the moon's surface composition and geology to identify signs of recent activity, including cracks, chaos terrain, and possible water vapor plumes venting from the interior, which could indicate ongoing geological dynamism and ocean-crust connectivity.[5] A critical component involves measuring Europa's induced magnetic field to confirm the ocean's existence, depth, and salinity, as the conductive saltwater layer generates a detectable signature in response to Jupiter's powerful magnetosphere.[11] These investigations will be conducted during the mission's primary phase, orbiting Jupiter for over four years starting in 2030, with 49 close flybys of Europa at altitudes ranging from 25 to 100 kilometers to gather high-resolution data.[3]Scientific strategy

The Europa Clipper mission adopts a non-orbiting strategy to investigate Europa's habitability, performing more than 45 targeted flybys of the moon over the course of approximately 45 orbits around Jupiter during its 3.5-year science phase. This approach enables nearly global coverage of Europa's surface and subsurface without entering a high-radiation orbit around the moon itself, with closest-approach altitudes tailored to instrument requirements, such as 25 km for ice-penetrating radar observations to sound the ice shell thickness.[4][12] Data collection occurs in distinct phases to maximize scientific return: remote sensing instruments operate during distant passes to map composition, geology, and the broader plasma environment, while close flybys facilitate in-situ measurements like particle analysis and magnetic field sampling for detailed subsurface and ocean insights. Flyby geometries are optimized to align with these phases, allowing repeated revisits to key regions for temporal studies.[13][9] Instrument integration emphasizes coordinated observations across the payload, such as the simultaneous use of the Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) and Europa Imaging System (EIS) to detect water vapor plumes and characterize their composition and distribution during flybys. This synergy supports multi-wavelength analysis, combining ultraviolet spectroscopy with wide- and narrow-angle imaging to identify active geological processes potentially linked to the subsurface ocean.[14][15] Radiation mitigation is critical given Jupiter's intense magnetospheric belts, with the spacecraft oriented to direct high-radiation flux away from sensitive avionics by positioning the high-gain antenna as a shield during transits through hazardous zones. Safe orientations behind the antenna's gold-plated molybdenum dish, along with a dedicated radiation vault for electronics, limit cumulative exposure to extend operational life.[16][17] The mission anticipates acquiring over 10,000 images and spectra, necessitating onboard prioritization to transmit the highest-value data given bandwidth constraints from the distant Jupiter system. Compression and selective downlinking ensure efficient use of the limited 160 kbps average rate via NASA's Deep Space Network.[18][19]Historical development

Background and early proposals

The discoveries made by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from December 1995 to September 2003, provided the foundational evidence for a subsurface ocean on Europa. Galileo's magnetometer detected an induced magnetic field around the moon, indicating the presence of a global layer of electrically conductive material—likely a salty ocean—beneath the icy surface, as Jupiter's magnetic field interacted with this layer to generate secondary fields.[20] Additionally, high-resolution images from Galileo revealed extensive "chaos terrain" regions, characterized by disrupted and fractured ice plates, suggesting recent geological activity and possible connections between the surface and underlying ocean through cryovolcanic processes or upwelling.[21] Following these findings, scientists estimated Europa's ice shell to be approximately 10–30 km thick, overlaying a vast ocean potentially twice the volume of Earth's combined surface and groundwater. This structure raised key questions about the ocean's chemistry, habitability, and interaction with the ice shell, necessitating missions with higher-resolution imaging and in-situ measurements to assess factors like salinity, pH, and organic compounds that could support life.[22] In the 1990s, as Galileo data emerged, NASA and ESA scientists began advocating for dedicated Europa exploration, emphasizing the moon's potential as a prime target for astrobiology in the outer solar system. This early push culminated in the 2003 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which prioritized a Europa mission as a flagship opportunity.[7] Early mission concepts in the 2000s built on this momentum, including NASA's Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JIMO), proposed in 2003 to study Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto using nuclear propulsion for multiple flybys and orbits, but canceled in 2005 due to technical and budgetary challenges.[23] Subsequently, the international Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM), jointly developed by NASA and ESA and announced in 2009, envisioned complementary orbiters—the NASA-led Jupiter Europa Orbiter and the ESA-led Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter—to comprehensively investigate the Jovian system, though it was canceled in 2011 amid rising costs and shifting priorities.[24]Funding and project approval

The 2013-2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, identified a flagship mission to Jupiter's moon Europa as the highest priority for exploration of the outer solar system, emphasizing its potential habitability due to evidence of a subsurface ocean. The survey estimated the cost of a full orbiter mission at approximately $4.7 billion, but budgetary constraints led NASA to pursue a more affordable multiple-flyby architecture known as the Europa Clipper, designed to achieve key science objectives through dozens of close passes by the moon without entering orbit.[25] This scaled-down approach aimed to reduce costs while maintaining the mission's focus on assessing Europa's ice shell, ocean, and composition. In April 2015, NASA officially selected the multiple-flyby mission concept for further development, marking a pivotal step in project approval after years of concept studies.[3] Later that year, in May 2015, NASA announced the selection of nine science instruments through a competitive peer-review process involving proposals from U.S. research institutions, prioritizing those that could best investigate Europa's habitability despite radiation challenges in the Jovian environment.[26] The initial funding proposal for the Clipper mission targeted a lifecycle cost of around $2 billion, excluding launch, with NASA requesting $15 million in fiscal year 2015 to initiate formulation activities; however, Congress appropriated significantly more—$80 million—to accelerate progress and affirm the mission's priority over other potential outer planet explorations.[27] This congressional support reflected the Decadal Survey's influence and helped secure the mission's trajectory amid competing demands within NASA's Planetary Science Division. Project approval advanced in April 2017 when the mission passed Key Decision Point B, authorizing entry into the implementation phase with a confirmed development plan and projected total cost of approximately $4.25 billion at the time, encompassing spacecraft build, instruments, and operations but excluding launch vehicle costs.[28] The mission is led by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, which manages overall development, while the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, leads spacecraft design and integration in close collaboration with JPL, leveraging expertise from prior missions like New Horizons.[29] This partnership structure, established early in the approval process, distributed responsibilities to optimize costs and technical execution. Despite disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused schedule delays and minor cost increases due to remote work and supply chain issues, NASA confirmed the mission's path forward in February 2021 by selecting a commercial launch vehicle—SpaceX's Falcon Heavy—for an October 2024 liftoff, avoiding reliance on the more expensive Space Launch System and saving an estimated $2 billion.[30][31] This decision, coupled with stable congressional appropriations averaging $400-500 million annually through fiscal year 2023, solidified funding stability and enabled continued progress toward launch.[32] By launch in October 2024, the mission's total estimated cost had risen to about $5.2 billion, reflecting adjustments for inflation, enhanced radiation shielding, and extended operations planning, yet remaining aligned with flagship mission benchmarks.[32]Design formulation and construction

The formulation phase of NASA's Europa Clipper mission, from 2017 to 2020, focused on refining the spacecraft's baseline design after entering Phase B in February 2017. Engineers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), serving as the mission's lead, established the core architecture to achieve the mission's habitability objectives while developing descope options to address budget limitations, including potential reductions in the number of Europa flybys from the planned 45 to fewer passes if funding required adjustments. This phase emphasized cost-effective strategies, drawing from earlier studies that explored reduced-scope configurations to ensure feasibility within congressional allocations.[25][33] A pivotal milestone was the Critical Design Review in 2021, which scrutinized the detailed engineering plans for the spacecraft, instruments, and operations, confirming readiness to transition from design to fabrication. This review incorporated feedback on descope scenarios and validated the integration of science payloads with the spacecraft bus.[34] Fabrication and assembly occurred primarily from 2020 to 2023 at APL's facilities in Laurel, Maryland, where teams constructed the spacecraft bus and integrated its nine science instruments. Key milestones included the initial hardware assembly starting in March 2022 and the deployment testing of the 28-foot (8.5-meter) magnetometer boom in June 2023 to verify its extension mechanism for measuring Europa's magnetic field. Assembly faced significant challenges in sourcing and incorporating radiation-hardened electronics, shielded within a titanium and aluminum vault to endure Jupiter's intense radiation belts, which can deliver doses equivalent to millions of rads over the mission lifetime. The fully fueled spacecraft reached a launch mass of approximately 5,800 kilograms (12,800 pounds), balancing structural integrity with propulsion needs for its 1.8-billion-mile journey.[35][36][37] Environmental testing commenced in 2023, simulating vibration, thermal extremes, and vacuum conditions to qualify the assembled spacecraft for launch, with full integration completing ahead of shipment to Kennedy Space Center in May 2024.[38]Testing and launch preparations