Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Near-Earth object

View on Wikipedia

| Near-Earth object | |

|---|---|

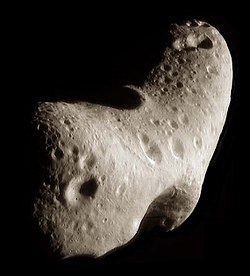

Nucleus of near-Earth comet 103P/Hartley as seen by NASA's Deep Impact probe | |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | Small Solar System body |

| Found | within 1.3 AU from the Sun |

| External links | |

A near-Earth object (NEO) is any small Solar System body orbiting the Sun whose closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) is less than 1.3 times the Earth–Sun distance (astronomical unit, AU).[2] This definition applies to the object's orbit around the Sun, rather than its current position, thus an object with such an orbit is considered an NEO even at times when it is far from making a close approach of Earth. If an NEO's orbit crosses the Earth's orbit, and the object is larger than 140 meters (460 ft) across, it is considered a potentially hazardous object (PHO).[3] Most known PHOs and NEOs are asteroids, but about a third of a percent are comets.[1]

There are over 37,000 known near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) and over 120 known short-period near-Earth comets (NECs).[1] A number of solar-orbiting meteoroids were large enough to be tracked in space before striking Earth. It is now widely accepted that collisions in the past have had a significant role in shaping the geological and biological history of Earth.[4] Asteroids as small as 20 metres (66 ft) in diameter can cause significant damage to the local environment and human populations.[5] Larger asteroids penetrate the atmosphere to the surface of the Earth, producing craters if they impact a continent or tsunamis if they impact the sea. Interest in NEOs has increased since the 1980s because of greater awareness of this risk. Asteroid impact avoidance by deflection is possible in principle, and methods of mitigation are being researched.[6]

Two scales, the simple Torino scale and the more complex Palermo scale, rate the risk presented by an identified NEO based on the probability of it impacting the Earth and on how severe the consequences of such an impact would be. Some NEOs have had temporarily positive Torino or Palermo scale ratings after their discovery. Since 1998, the United States, the European Union, and other nations have been scanning the sky for NEOs in an effort called Spaceguard.[7] The initial US Congress mandate to NASA to catalog at least 90% of NEOs that are at least 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) in diameter, sufficient to cause a global catastrophe, was met by 2011.[8] In later years, the survey effort was expanded[9] to include smaller objects[10] which have the potential for large-scale, though not global, damage.

NEOs have low surface gravity, and many have Earth-like orbits that make them easy targets for spacecraft.[11][12] As of December 2024[update], five near-Earth comets[13][14][15] and six near-Earth asteroids,[16][17][18][19][20] one of them with a moon,[20] have been visited by spacecraft. Samples of three have been returned to Earth,[21][22] and one successful deflection test was conducted.[23] Similar missions are in progress. Preliminary plans for commercial asteroid mining have been drafted by private startup companies, but few of these plans were pursued.[24]

Definitions

[edit]

Near-Earth objects (NEOs) are formally defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as all small Solar System bodies with orbits around the Sun that are at least partially closer than 1.3 astronomical units (AU; Sun–Earth distance) from the Sun.[25] This definition excludes larger bodies such as planets, like Venus; natural satellites which orbit bodies other than the Sun, like Earth's Moon; and artificial bodies orbiting the Sun. A small Solar System body can be an asteroid or a comet, thus an NEO is either a near-Earth asteroid (NEA) or a near-Earth comet (NEC). The organisations cataloging NEOs further limit their definition of NEO to objects with an orbital period under 200 years, a restriction that applies to comets in particular,[2][26] but this approach is not universal.[25] Some authors further restrict the definition to orbits that are at least partly further than 0.983 AU away from the Sun.[27][28] NEOs are thus not necessarily currently near the Earth, but they can potentially approach the Earth relatively closely. Many NEOs have complex orbits due to constant perturbation by the Earth's gravity, and some of them can temporarily change from an orbit around the Sun to one around the Earth, but the term is applied flexibly for these objects, too.[29]

The orbits of some NEOs intersect that of the Earth, so they pose a collision danger.[3] These are considered potentially hazardous objects (PHOs) if their estimated diameter is above 140 meters. PHOs include potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs).[30][31] PHAs are defined based on two parameters relating to respectively their potential to approach the Earth dangerously closely and the estimated consequences that an impact would have if it occurs.[2] Objects with both an Earth minimum orbit intersection distance (MOID) of 0.05 AU or less and an absolute magnitude of 22.0 or brighter (a rough indicator of large size) are considered PHAs. Objects that either cannot approach closer to the Earth than 0.05 AU (7,500,000 km; 4,600,000 mi), or which are fainter than H = 22.0 (about 140 m (460 ft) in diameter with assumed albedo of 14%), are not considered PHAs.[2]

History of human awareness of NEOs

[edit]

The first near-Earth objects to be observed by humans were comets. Their extraterrestrial nature was recognised and confirmed only after Tycho Brahe tried to measure the distance of a comet through its parallax in 1577 and the lower limit he obtained was well above the Earth diameter; the periodicity of some comets was first recognised in 1705, when Edmond Halley published his orbit calculations for the returning object now known as Halley's Comet.[32] The 1758–1759 return of Halley's Comet was the first comet appearance predicted.[33]

The extraterrestrial origin of meteors (shooting stars) was only recognised on the basis of the analysis of the 1833 Leonid meteor shower by astronomer Denison Olmsted. The 33-year period of the Leonids led astronomers to suspect that they originate from a comet that would today be classified as an NEO, which was confirmed in 1867, when astronomers found that the newly discovered comet 55P/Tempel–Tuttle has the same orbit as the Leonids.[34]

The first near-Earth asteroid to be discovered was 433 Eros in 1898.[35] The asteroid was subject to several extensive observation campaigns, primarily because measurements of its orbit enabled a precise determination of the then imperfectly known distance of the Earth from the Sun.[36]

Encounters with Earth

[edit]If a near-Earth object is near the part of its orbit closest to Earth's at the same time Earth is at the part of its orbit closest to the near-Earth object's orbit, the object has a close approach, or, if the orbits intersect, could even impact the Earth or its atmosphere.

Close approaches

[edit]As of May 2019[update], only 23 comets have been observed to pass within 0.1 AU (15,000,000 km; 9,300,000 mi) of Earth, including 10 which are or have been short-period comets.[37] Two of these near-Earth comets, Halley's Comet and 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann, have been observed during multiple close approaches.[37] The closest observed approach was 0.0151 AU (5.88 LD) for Lexell's Comet on July 1, 1770.[37] After an orbit change due to a close approach of Jupiter in 1779, this object is no longer an NEC. The closest approach ever observed for a current short-period NEC is 0.0229 AU (8.92 LD) for Comet Tempel–Tuttle in 1366.[37] Orbital calculations show that P/1999 J6 (SOHO), a faint sungrazing comet and confirmed short-period NEC observed only during its close approaches to the Sun,[38] passed Earth undetected at a distance of 0.0120 AU (4.65 LD) on June 12, 1999.[39]

In 1937, 800 m (2,600 ft) asteroid 69230 Hermes was discovered when it passed the Earth at twice the distance of the Moon.[40] On June 14, 1968, the 1.4 km (0.87 mi) diameter asteroid 1566 Icarus passed Earth at a distance of 0.0425 AU (6,360,000 km), or 16.5 times the distance of the Moon.[41] During this approach, Icarus became the first minor planet to be observed using radar.[42][43] This was the first close approach predicted years in advance, since Icarus had been discovered in 1949.[44] The first near-Earth asteroid known to have passed Earth closer than the distance of the Moon was 1991 BA, a 5–10 m (16–33 ft) body which passed at a distance of 170,000 km (110,000 mi).[45] As NEA surveys were enhanced, at least one such object was observed each year from 2001, at least a dozen from 2005, and over a hundred from 2020.[46][47]

As astronomers became able to discover ever smaller and fainter and ever more numerous near-Earth objects, they began to routinely observe and catalogue close approaches.[46][47] As of December 2024[update], the closest approach without atmospheric or ground impact ever detected was an encounter with 5–11 m (16–36 ft) asteroid 2020 VT4 on November 14, 2020,[47] with a minimum distance of about 6,750 km (4,190 mi) from the Earth's centre, or about 380 km (240 mi) above its surface.[48] On November 8, 2011, asteroid (308635) 2005 YU55, relatively large at about 400 m (1,300 ft) in diameter, passed within 324,930 km (201,900 mi) (0.845 lunar distances) of Earth.[49] On February 15, 2013, the 30 m (98 ft) asteroid 367943 Duende (2012 DA14) passed approximately 27,700 km (17,200 mi) above the surface of Earth, closer than satellites in geosynchronous orbit.[50] The asteroid was not visible to the unaided eye. This was the first sub-lunar close passage of an object discovered during a previous passage, and was thus the first to be predicted well in advance.[51] On October 8, 2025, asteroid 2025 TN2, approximately 87 feet (≈27 m) in diameter, passed safely by Earth at a distance of 1.34 million km (≈0.00895 AU). On the same day, three additional small asteroids — 2025 SJ29, 2025 TF1, and 2020 QU5, measuring about 55 ft, 65 ft, and 81 ft respectively — also made close approaches, all without any risk of impact.[52]

Earth-grazers

[edit]Some small asteroids that enter the upper atmosphere of Earth at a shallow angle remain intact and leave the atmosphere again, continuing on a solar orbit. During the passage through the atmosphere, due to the burning of its surface, such an object can be observed as an Earth-grazing fireball.

On August 10, 1972, a meteor that became known as the 1972 Great Daylight Fireball was witnessed by many people and even filmed as it moved north over the Rocky Mountains from the U.S. Southwest to Canada.[53] It passed within 58 km (36 mi) of the Earth's surface.[54]

On October 13, 1990, Earth-grazing meteoroid EN131090 was observed above Czechoslovakia and Poland, moving at 41.74 km/s (93,370 mph; 150,264 km/h) along a 409 km (254 mi) trajectory from south to north. The closest approach to the Earth was 98.67 km (61.31 mi) above the surface. It was captured by two all-sky cameras of the European Fireball Network, which for the first time enabled geometric calculations of the orbit of such a body.[55]

Impacts

[edit]When a near-Earth object impacts Earth, objects up to a few tens of metres across ordinarily explode in the upper atmosphere (most of them harmlessly), with most or all of the solids vaporized and only small amounts of meteorites arriving to the Earth surface. Larger objects, by contrast, hit the water surface, forming tsunami waves, or the solid surface, forming impact craters.[56]

The frequency of impacts of objects of various sizes is estimated on the basis of orbit simulations of NEO populations, the frequency of impact craters on the Earth and the Moon, and the frequency of close encounters.[57][58] The study of impact craters indicates that impact frequency has been more or less steady for the past 3.5 billion years, which requires a steady replenishment of the NEO population from the asteroid main belt.[27] One impact model based on widely accepted NEO population models estimates the average time between the impact of two stony asteroids with a diameter of at least 4 m (13 ft) at about one year; for asteroids 7 m (23 ft) across (which impacts with as much energy as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, approximately 15 kilotonnes of TNT) at five years, for asteroids 60 m (200 ft) across (an impact energy of 10 megatons, comparable to the Tunguska event in 1908) at 1,300 years, for asteroids 1 km (0.62 mi) across at 440 thousand years, and for asteroids 5 km (3.1 mi) across at 18 million years.[59] Some other models estimate similar impact frequencies,[27] while others calculate higher frequencies.[58] For Tunguska-sized (10 megaton) impacts, the estimates range from one event every 2,000–3,000 years to one event every 300 years.[58]

The second-largest observed event after the Tunguska meteor was a 1.1 megaton air blast in 1963 near the Prince Edward Islands between South Africa and Antarctica. However, this event was detected only by infrasound sensors,[60][61] which led to speculation that this may have been a nuclear test.[62] The third-largest, but by far best-observed impact, was the Chelyabinsk meteor of 15 February 2013. A previously unknown 20 m (66 ft) asteroid exploded above this Russian city with an equivalent blast yield of 400–500 kilotons.[60] The calculated orbit of the pre-impact asteroid is similar to that of Apollo asteroid 2011 EO40, making the latter the meteor's possible parent body.[63]

On October 7, 2008, 20 hours after it was first observed and 11 hours after its trajectory has been calculated and announced, 4 m (13 ft) asteroid 2008 TC3 blew up 37 km (23 mi) above the Nubian Desert in Sudan. It was the first time that an asteroid was observed and its impact was predicted prior to its entry into the atmosphere as a meteor. 10.7 kilograms (23.6 lb) of meteorites were recovered after the impact.[64] As of December 2024[update], eleven impacts have been predicted, all of them small bodies that produced meteor explosions,[65] with some impacts in remote areas only detected by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization's International Monitoring System (IMS), a network of infrasound sensors designed to detect the detonation of nuclear devices.[66] Asteroid impact prediction remains in its infancy and successfully predicted asteroid impacts are rare. The vast majority of impacts recorded by IMS are not predicted.[67]

Observed impacts aren't restricted to the surface and atmosphere of Earth. Dust-sized NEOs have impacted man-made spacecraft, including the space probe Long Duration Exposure Facility, which collected interplanetary dust in low Earth orbit for six years from 1984.[68] Impacts on the Moon can be observed as flashes of light with a typical duration of a fraction of a second.[69] The first lunar impacts were recorded during the 1999 Leonid storm.[70] Subsequently, several continuous monitoring programs were launched.[69][71][72] A lunar impact that was observed on September 11, 2013, lasted 8 seconds, was likely caused by an object 0.6–1.4 m (2.0–4.6 ft) in diameter,[71] and created a new crater 40 m (130 ft) across, was the largest ever observed as of July 2019[update].[73]

Risk

[edit]

Through human history, the risk that any near-Earth object poses has been viewed having regard to both the culture and the technology of human society. Through history, humans have associated NEOs with changing risks, based on religious, philosophical or scientific views, as well as humanity's technological or economical capability to deal with such risks.[6] Thus, NEOs have been seen as omens of natural disasters or wars; harmless spectacles in an unchanging universe; the source of era-changing cataclysms[6] or potentially poisonous fumes (during Earth's passage through the tail of Halley's Comet in 1910);[74] and finally as a possible cause of a crater-forming impact that could even cause extinction of humans and other life on Earth.[6]

The potential of catastrophic impacts by near-Earth comets was recognised as soon as the first orbit calculations provided an understanding of their orbits: in 1694, Edmond Halley presented a theory that Noah's flood in the Bible was caused by a comet impact.[75]

Human perception of near-Earth asteroids as benign objects of fascination or killer objects with high risk to human society has ebbed and flowed during the short time that NEAs have been scientifically observed.[12] The 1937 close approach of Hermes and the 1968 close approach of Icarus first raised impact concerns among scientists. Icarus earned significant public attention due to alarmist news reports, while Hermes was considered a threat because it was lost after its discovery; thus its orbit and potential for collision with Earth were not known precisely.[44] Hermes was only re-discovered in 2003, and it is now known to be no threat for at least the next century.[40]

Scientists have recognised the threat of impacts that create craters much bigger than the impacting bodies and have indirect effects on an even wider area since the 1980s, with mounting evidence for the theory that the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (in which the non-avian dinosaurs died out) 65 million years ago was caused by a large asteroid impact.[6][76] On March 23, 1989, the 300 m (980 ft) diameter Apollo asteroid 4581 Asclepius (1989 FC) missed the Earth by 700,000 km (430,000 mi). If the asteroid had impacted it would have created the largest explosion in recorded history, equivalent to 20,000 megatons of TNT. It attracted widespread attention because it was discovered only after the closest approach.[77]

From the 1990s, a typical frame of reference in searches for NEOs has been the scientific concept of risk. The awareness of the wider public of the impact risk rose after the observation of the impact of the fragments of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 into Jupiter in July 1994.[6][76] In March 1998, early orbit calculations for recently discovered asteroid (35396) 1997 XF11 showed a potential 2028 close approach 0.00031 AU (46,000 km) from the Earth, well within the orbit of the Moon, but with a large error margin allowing for a direct hit. Further data allowed a revision of the 2028 approach distance to 0.0064 AU (960,000 km), with no chance of collision. By that time, inaccurate reports of a potential impact had caused a media storm.[44]

In 1998, the movies Deep Impact and Armageddon popularised the notion that near-Earth objects could cause catastrophic impacts.[76] Also at that time, a conspiracy theory arose about a supposed 2003 impact of a planet called Nibiru with Earth, which persisted on the internet as the predicted impact date was moved to 2012 and then 2017.[78]

Risk scales

[edit]There are two schemes for the scientific classification of impact hazards from NEOs, as a way to communicate the risk of impacts to the general public.

The simple Torino scale was established at an IAU workshop in Turin (Italian: Torino) in June 1999, in the wake of the public confusion about the impact risk of 1997 XF11.[79] It rates the risks of impacts in the next 100 years according to impact energy and impact probability, using integer numbers between 0 and 10:[80][81]

- ratings of 0 and 1 are of no concern to astronomers or the public,

- ratings of 2 to 4 are used for events with increasing magnitude of concern to astronomers trying to make more precise orbit calculations, but not yet a concern for the public,

- ratings of 5 to 7 are meant for impacts of increasing magnitude which are not certain but warrant public concern and governmental contingency planning over an increasing timescale,

- 8 to 10 would be used for certain collisions of increasing severity.

The more complex Palermo scale, established in 2002, compares the likelihood of an impact at a certain date to the probable number of impacts of a similar energy or greater until the possible impact, and takes the logarithm of this ratio. Thus, a Palermo scale rating can be any positive or negative real number, and risks of any concern are indicated by values above zero. Unlike the Torino scale, the Palermo scale is not sensitive to newly discovered small objects with an orbit known with low confidence.[82]

Highly rated risks

[edit]The National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA maintains an automated system to evaluate the threat from known NEOs over the next 100 years, which generates the continuously updated Sentry Risk Table.[83] All or nearly all of the objects are highly likely to drop off the list eventually as more observations come in, reducing the uncertainties and enabling more accurate orbital predictions.[83][84] When the close approach of a newly discovered asteroid is first put on a risk list with a significant risk, it is normal for the risk to first increase, regardless of whether the potential impact will eventually be ruled out or confirmed with the help of additional observations.[85] Similar tables are maintained by the Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre (NEOCC) of the European Space Agency (ESA)[86] and on the NEODyS (Near Earth Objects Dynamic Site) by the University of Pisa spin-off company SpaceDyS.[87]

In March 2002, (163132) 2002 CU11 became the first asteroid with a temporarily positive rating on the Torino Scale, with about a 1 in 9,300 chance of an impact in 2049.[88] Additional observations reduced the estimated risk to zero, and the asteroid was removed from the Sentry Risk Table in April 2002.[89] It is now known that within the next two centuries, 2002 CU11 will pass the Earth at a safe closest distance (perigee) of 0.00425 AU (636,000 km; 395,000 mi) on August 31, 2080.[90]

Asteroid (29075) 1950 DA has a diameter of about a kilometer (0.6 miles), and an impact would therefore be globally catastrophic. Although this asteroid will not strike for at least 800 years and thus has no Torino scale rating, it was added to the Sentry list in April 2002 as the first object with a Palermo scale value greater than zero.[25][91] The then-calculated 1 in 300 maximum chance of impact and +0.17 Palermo scale value was roughly 50% greater than the background risk of impact by all similarly large objects until 2880.[91][92] After additional radar[93] and optical observations, as of March 2025[update], the probability of this impact is assessed at 1 in 2,600.[83] The corresponding Palermo scale value of −0.92 is the second-highest for all objects on the Sentry List Table.[83]

On December 24, 2004, five days after discovery, 370 m (1,210 ft) asteroid 99942 Apophis was assigned a 4 on the Torino scale, the highest rating given to date, as the information available at the time translated to a 1.6% chance of Earth impact in April 2029.[94] As observations were collected over the next three days, the calculated chance of impact first increased to as high as 2.7%,[95] then fell back to zero, as the shrinking uncertainty zone for this close approach no longer included the Earth.[96] There was at that time still some uncertainty about potential impacts during later close approaches. However, as the precision of orbital calculations improved due to additional observations, the risk of impact at any date was eliminated[97] and Apophis was removed from the Sentry Risk Table in February 2021.[89]

As of March 2025[update], 2010 RF12 was listed on the Sentry List Table with the highest chance of impacting Earth, at 1 in 10 on September 5, 2095.[83] At only 7 m (23 ft) across, the asteroid however is much too small to be considered a potentially hazardous asteroid and it poses no serious threat: the possible 2095 impact therefore rates only −2.97 on the Palermo Scale.[83]

In January 2025, 55 m (180 ft) asteroid 2024 YR4 reached a 3 rating on the Torino scale for a possible impact on December 22, 2032, triggering an action plan to schedule observations with more powerful telescopes as the object recedes and gets dimmer, to determine its orbit with more precision and thus refine the impact risk prediction.[98] In February 2025, the impact risk peaked at 1 in 32, then dropped below 1 in 1000 and the Torino scale rating was reduced to 0.[99] As of 2 March 2025[update], the impact risk for the 2032 encounter was down to 1 in 120,000.[83] By April, 2024 YR4 was on the other hand estimated to have a 4% chance of impacting a 70% waning gibbous moon on 22 December 2032[100] around 15:17 to 15:21 UTC.[101]

Projects to minimize the threat

[edit]A year before the 1968 close approach of asteroid Icarus, Massachusetts Institute of Technology students launched Project Icarus, devising a plan to deflect the asteroid with rockets in case it was found to be on a collision course with Earth.[102] Project Icarus received wide media coverage, and inspired the 1979 disaster movie Meteor, in which the US and the USSR join forces to blow up an Earth-bound fragment of an asteroid hit by a comet.[103]

The first astronomical program dedicated to the discovery of near-Earth asteroids was the Palomar Planet-Crossing Asteroid Survey. The link to impact hazard, the need for dedicated survey telescopes and options to head off an eventual impact were first discussed at a 1981 interdisciplinary conference in Snowmass, Colorado.[76] Plans for a more comprehensive survey, named the Spaceguard Survey, were developed by NASA from 1992, under a mandate from the United States Congress.[104][105] To promote the survey on an international level, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) organised a workshop at Vulcano, Italy in 1995,[104] and set up The Spaceguard Foundation also in Italy a year later.[7] In 1998, the United States Congress gave NASA a mandate to detect 90% of near-Earth asteroids over 1 km (0.62 mi) diameter (that threaten global devastation) by 2008.[105][106]

Several surveys have undertaken "Spaceguard" activities (an umbrella term), including Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR), Spacewatch, Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT), Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search (LONEOS), Catalina Sky Survey (CSS), Campo Imperatore Near-Earth Object Survey (CINEOS), Japanese Spaceguard Association, Asiago-DLR Asteroid Survey (ADAS) and Near-Earth Object WISE (NEOWISE). As a result, the ratio of the known and the estimated total number of near-Earth asteroids larger than 1 km in diameter rose from about 20% in 1998 to 65% in 2004,[7] 80% in 2006,[106] and 93% in 2011. The original Spaceguard goal has thus been met, only three years late.[8][107] As of December 2024[update], 867 NEAs larger than 1 km have been discovered, of which one was discovered in 2024 and two in 2023.[1]

In 2005, the original USA Spaceguard mandate was extended by the George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey Act, which calls for NASA to detect 90% of NEOs with diameters of 140 m (460 ft) or greater, by 2020.[9] In January 2016, NASA announced the creation of the Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) to coordinate an effective threat assessment, response and mitigation effort, which reinforced the goal to detect 90% of NEOs 140 m (460 ft) or greater, but without a deadline.[10][108] In September 2020, it was estimated that about half of these have been found, but objects of this size hit the Earth only about once in 30,000 years.[109] In December 2023, using a lower absolute brightness estimate for smaller asteroids, the ratio of discovered NEOs with diameters of 140 m (460 ft) or greater was estimated at 38%.[110] The Chile-based Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which will survey the southern sky for transient events from 2025, is expected to increase the number of known asteroids by a factor of 10 to 100 and increase the ratio of known NEOs with diameters of 140 m (460 ft) or greater to at least 60%,[111] while the NEO Surveyor satellite, to be launched in 2027, is expected to push the ratio to 76% during its 5-year mission.[110]

Survey programs aim to identify threats years in advance, giving humanity time to prepare a space mission to avert the threat.

REP. STEWART: ... are we technologically capable of launching something that could intercept [an asteroid]? ...

DR. A'HEARN: No. If we had spacecraft plans on the books already, that would take a year ... I mean a typical small mission ... takes four years from approval to start to launch ...

— Rep. Chris Stewart (R, UT) and Dr. Michael F. A'Hearn, April 10, 2013, United States Congress[112]

The ATLAS project, by contrast, aims to find impacting asteroids shortly before impact, much too late for deflection maneuvers but still in time to evacuate and otherwise prepare the affected Earth region.[113] Another project, the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), which surveys for objects that change their brightness rapidly,[114] also detects asteroids passing close to Earth.[115]

Scientists involved in NEO research have also considered options for actively averting the threat if an object is found to be on a collision course with Earth.[76] All viable methods aim to deflect rather than destroy the threatening NEO, because the fragments would still cause widespread destruction.[13] Deflection, which means a change in the object's orbit months to years prior to the predicted impact, also requires orders of magnitude less energy.[13]

Number and classification

[edit]

When an NEO is detected, like all other small Solar System bodies, its positions and brightness are submitted to the (IAU's) Minor Planet Center (MPC) for cataloging. The MPC maintains separate lists of confirmed NEOs and potential NEOs.[116][117] The MPC maintains a separate list for the potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs).[30] NEOs are also catalogued by two separate units of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) of NASA: the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS)[118] and the Solar System Dynamics Group.[119] CNEOS's catalog of near-Earth objects includes the approach distances of asteroids and comets.[47] NEOs are also catalogued by a unit of ESA, the Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre (NEOCC).[120]

Near-Earth objects are classified as meteoroids, asteroids, or comets depending on size, composition, and orbit. Those which are asteroids can additionally be members of an asteroid family, and comets create meteoroid streams that can generate meteor showers.

As of December 30, 2024[update] and according to statistics maintained by CNEOS, 37,378 NEOs have been discovered. Only 123 (0.33%) of them are comets, whilst 37,255 (99.67%) are asteroids. 2,465 of those NEOs are classified as potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs).[1]

As of February 2, 2025[update], 1,886 NEAs appear on the Sentry impact risk page at the NASA website.[83] All but 106 of these NEAs are less than 50 meters in diameter, only one recently discovered object has an impact risk meriting a Torino Scale rating higher than zero, while none have a Palermo scale rating higher than zero.[80]

Observational biases

[edit]The main problem with estimating the number of NEOs is that the probability of detecting one is influenced by a number of aspects of the NEO, starting naturally with its size but also including the characteristics of its orbit and the reflectivity of its surface.[121] What is easily detected will be more counted, and these observational biases need to be compensated when trying to calculate the number of bodies in a population from the list of its detected members.[121]

Bigger asteroids reflect more light, and the two biggest near-Earth objects, 433 Eros and 1036 Ganymed, were naturally also among the first to be detected.[122] 1036 Ganymed is about 35 km (22 mi) in diameter and 433 Eros is about 17 km (11 mi) in diameter.[122] Meanwhile, the apparent brightness of objects that are closer is higher, introducing a bias that favours the discovery of NEOs of a given size that get closer to Earth.[123]

Earth-based astronomy requires dark skies and hence nighttime observations, and even space-based telescopes avoid looking into directions close to the Sun, thus most NEO surveys are blind towards objects passing Earth on the side of the Sun.[123][124] This bias is further enhanced by the effect of phase: the narrower the angle of the asteroid and the Sun from the observer, the lesser part of the observed side of the asteroid will be illuminated.[123] Another bias results from the different surface brightness or albedo of the objects, which can make a large but low-albedo object as bright as a small but high-albedo object.[123][125] In addition, the reflexivity of asteroid surfaces is not uniform but increases towards the direction opposite of illumination, resulting in the phenomenon of phase darkening, which makes asteroids even brighter when the Earth is close to the axis of sunlight.[123] An asteroid's observed albedo usually has a strong peak or opposition surge very close to the direction opposite of the Sun.[123] Different surfaces display different levels of phase darkening, and research showed that, on top of albedo bias, this favours the discovery of silicon-rich S-type asteroids over carbon-rich C types, for example.[123] As a result of these observational biases, in Earth-based surveys, NEOs tended to be discovered when they were in opposition, that is, opposite from the Sun when viewed from the Earth.[110]

The most practical way around many of these biases is to use thermal infrared telescopes in space that observe their thermal emissions instead of the visible light they reflect, with a sensitivity that is almost independent of the illumination.[110][125] In addition, space-based telescopes in an orbit around the Sun in the shadow of the Earth can make observations as close as 45 degrees to the direction of the Sun.[124]

Further observational biases favour objects that have more frequent encounters with the Earth, which makes the detection of Atens more likely than that of Apollos; and objects that move slower when encountering the Earth, which makes the detection of NEAs with low eccentricities more likely.[126]

Such observational biases must be identified and quantified to determine NEO populations, as studies of asteroid populations then take those known observational selection biases into account to make a more accurate assessment.[127] In the year 2000 and taking into account all known observational biases, it was estimated that there are approximately 900 near-Earth asteroids of at least kilometer size, or technically and more accurately, with an absolute magnitude brighter than 17.75.[121]

Near-Earth asteroids

[edit]

These are asteroids in a near-Earth orbit without the tail or coma of a comet. As of December 2024[update], 37,255 near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) are known, 2,465 of which are both sufficiently large and may come sufficiently close to Earth to be classified as potentially hazardous.[1]

NEAs survive in their orbits for just a few million years.[27] They are eventually eliminated by planetary perturbations, causing ejection from the Solar System or a collision with the Sun, a planet, or other celestial body.[27] With orbital lifetimes short compared to the age of the Solar System, new asteroids must be constantly moved into near-Earth orbits to explain the observed asteroids. The accepted origin of these asteroids is that main-belt asteroids are moved into the inner Solar System through orbital resonances with Jupiter.[27] The interaction with Jupiter through the resonance perturbs the asteroid's orbit and it comes into the inner Solar System. The asteroid belt has gaps, known as Kirkwood gaps, where these resonances occur as the asteroids in these resonances have been moved onto other orbits. New asteroids migrate into these resonances, due to the Yarkovsky effect that provides a continuing supply of near-Earth asteroids.[128] Compared to the entire mass of the asteroid belt, the mass loss necessary to sustain the NEA population is relatively small; totalling less than 6% over the past 3.5 billion years.[27] The composition of near-Earth asteroids is comparable to that of asteroids from the asteroid belt, reflecting a variety of asteroid spectral types.[129]

A small number of NEAs are extinct comets that have lost their volatile surface materials, although having a faint or intermittent comet-like tail does not necessarily result in a classification as a near-Earth comet, making the boundaries somewhat fuzzy. The rest of the near-Earth asteroids are driven out of the asteroid belt by gravitational interactions with Jupiter.[27][130]

Many asteroids have natural satellites (minor-planet moons). As of December 2024[update], 104 NEAs were known to have at least one moon, including five known to have two moons.[131] The asteroid 3122 Florence, one of the largest PHAs[30] with a diameter of 4.5 km (2.8 mi), has two moons measuring 100–300 m (330–980 ft) across, which were discovered by radar imaging during the asteroid's 2017 approach to Earth.[132]

In May 2022, an algorithm known as Tracklet-less Heliocentric Orbit Recovery or THOR and developed by University of Washington researchers to discover asteroids in the solar system was announced as a success.[133] The International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center confirmed a series of first candidate asteroids identified by the algorithm.[134]

Size distribution

[edit]

While the size of a very small fraction of these asteroids is known to better than 1%, from radar observations, from images of the asteroid surface, or from stellar occultations, the diameter of the vast majority of near-Earth asteroids has only been estimated on the basis of their brightness and a representative asteroid surface reflectivity or albedo, which is commonly assumed to be 14%.[118] Such indirect size estimates are uncertain by over a factor of 2 for individual asteroids, since asteroid albedos can range at least as low as 5% and as high as 30%. This makes the volume of those asteroids uncertain by a factor of 8, and their mass by at least as much, since their assumed density also has its own uncertainty. Using this crude method, an absolute magnitude of 17.75 roughly corresponds to a diameter of 1 km (0.62 mi)[118] and an absolute magnitude of 22.0 to a diameter of 140 m (460 ft).[2] Diameters of intermediate precision, better than from an assumed albedo but not nearly as precise as good direct measurements, can be obtained from the combination of reflected light and thermal infrared emission, using a thermal model of the asteroid to estimate both its diameter and its albedo. The reliability of this method, as applied by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer and NEOWISE missions, has been the subject of a dispute between experts, with the 2018 publication of two independent analyses, one criticising and another giving results consistent with the WISE method.[135] A 2023 study re-evaluated the relationship of brightness, albedo and diameter. For many objects with a diameter larger than 1 km, brightness estimates were reduced slightly. Meanwhile, based on new albedo estimates of smaller objects, the study found that H = 23 best corresponds to a diameter of 140 m.[110]

In 2000, NASA reduced from 1,000–2,000 to 500–1,000 its estimate of the number of existing near-Earth asteroids over one kilometer in diameter, or more exactly brighter than an absolute magnitude of 17.75.[136][137] Shortly thereafter, the LINEAR survey provided an alternative estimate of 1,227+170

−90.[138] In 2011, on the basis of NEOWISE observations, the estimated number of one-kilometer NEAs was narrowed to 981±19 (of which 93% had been discovered at the time), while the number of NEAs larger than 140 meters across was estimated at 13,200±1,900.[8][107] The NEOWISE estimate differed from other estimates primarily in assuming a slightly lower average asteroid albedo, which produces larger estimated diameters for the same asteroid brightness. This resulted in 911 then known asteroids at least 1 km across, as opposed to the 830 then listed by CNEOS from the same inputs but assuming a slightly higher albedo.[139] In 2017, two studies using an improved statistical method reduced the estimated number of NEAs brighter than absolute magnitude 17.75 (approximately over one kilometer in diameter) slightly to 921±20.[140][141] The estimated number of near-Earth asteroids brighter than absolute magnitude of 22.0 (approximately over 140 m across) rose to 27,100±2,200, double the WISE estimate, of which about a fourth were known at the time.[141] The number of asteroids brighter than H = 25, which corresponds to about 40 m (130 ft) in diameter, is estimated at 840,000±23,000—of which about 1.3 percent had been discovered by February 2016; the number of asteroids brighter than H = 30 (larger than 3.5 m (11 ft)) is estimated at 400±100 million—of which about 0.003 percent had been discovered by February 2016.[141]

A September 2021 study revised the estimated number of NEAs with a diameter larger than 1 km (using both WISE data and the absolute brightness lower than 17.75 as proxy) slightly upwards to 981±19, of which 911 were discovered at the time, but reduced the estimated number of asteroids brighter than absolute magnitude of 22.0 (as proxy for a diameter of 140 m) to under 20,000, of which about half were discovered at the time.[109] The 2023 study that re-evaluated the relationship of average absolute brightness, albedo and diameter confirmed the ratios of the number of discovered and estimated total asteroids of different sizes in the 2021 study, but by changing the proxy for a diameter of 140 m to H = 23, it estimated that only about 44% of the estimated 35,000 total larger than that have been discovered by the end of 2022.[110] As of January 2024[update], NEO catalogues still use H = 22 as proxy for a diameter of 140 m.[2]

As of December 30, 2024[update], and using diameters mostly estimated crudely from a measured absolute magnitude and an assumed albedo, 867 NEAs listed by CNEOS, including 152 PHAs, measure at least 1 km in diameter, and 11,167 known NEAs, including 2,465 PHAs, are larger than 140 m in diameter.[1]

The smallest known near-Earth asteroid is 2015 FF415 with an absolute magnitude of 34.34,[119] corresponding to an estimated diameter of about 0.5 m (1.6 ft).[142] The largest such object is 1036 Ganymed,[119] with an absolute magnitude of 9.18 and directly measured irregular dimensions which are equivalent to a diameter of about 38 km (24 mi).[143]

Orbital classification

[edit]

Near-Earth asteroids are divided into groups based on their semi-major axis (a), perihelion distance (q), and aphelion distance (Q):[2][26]

- The Atiras or Apoheles have orbits strictly inside Earth's orbit: an Atira asteroid's aphelion distance (Q) is smaller than Earth's perihelion distance (0.983 AU). That is, Q < 0.983 AU, which implies that the asteroid's semi-major axis is also less than 0.983 AU.[144] This group includes asteroids on orbits that never get close to Earth, including the sub-group of ꞌAylóꞌchaxnims, which orbit the Sun entirely within the orbit of Venus[145] and which include the hypothetical sub-group of Vulcanoids, which have orbits entirely within the orbit of Mercury.[146]

- The Atens have a semi-major axis of less than 1 AU and cross Earth's orbit. Mathematically, a < 1.0 AU and Q > 0.983 AU. (0.983 AU is Earth's perihelion distance.)

- The Apollos have a semi-major axis of more than 1 AU and cross Earth's orbit. Mathematically, a > 1.0 AU and q < 1.017 AU. (1.017 AU is Earth's aphelion distance.)

- The Amors have orbits strictly outside Earth's orbit: an Amor asteroid's perihelion distance (q) is greater than Earth's aphelion distance (1.017 AU). Amor asteroids are also near-Earth objects so q < 1.3 AU. In summary, 1.017 AU < q < 1.3 AU. (This implies that the asteroid's semi-major axis (a) is also larger than 1.017 AU.) Some Amor asteroid orbits cross the orbit of Mars.

Some authors define Atens differently: they define it as being all the asteroids with a semi-major axis of less than 1 AU.[147][148] That is, they consider the Atiras to be part of the Atens.[148] Historically, until 1998, there were no known or suspected Atiras, so the distinction wasn't necessary.

Atiras and Amors do not cross the Earth's orbit and are not immediate impact threats, but their orbits may change to become Earth-crossing orbits in the future.[27][149]

As of December 30, 2024[update], 34 Atiras, 2,952 Atens, 21,132 Apollos and 13,137 Amors have been discovered and cataloged.[1]

Co-orbital asteroids

[edit]

Most NEAs have orbits that are significantly more eccentric than that of the Earth and the other major planets and their orbital planes can tilt several degrees relative to that of the Earth. NEAs which have orbits that do resemble the Earth's in eccentricity, inclination and semi-major axis are grouped as Arjuna asteroids.[150] Within this group are NEAs that have the same orbital period as the Earth, or a co-orbital configuration, which corresponds to an orbital resonance at a ratio of 1:1. All co-orbital asteroids have special orbits that are relatively stable and, paradoxically, can prevent them from getting close to Earth:

- Trojans: Near the orbit of a planet, there are five gravitational equilibrium points, the Lagrangian points, in which an asteroid would orbit the Sun in fixed formation with the planet. Two of these, 60 degrees ahead and behind the planet along its orbit (designated L4 and L5 respectively) are stable; that is, an asteroid near these points would stay there for thousands or even millions of years in spite of light perturbations by other planets and by non-gravitational forces. Trojans circle around L4 or L5 on paths resembling a tadpole.[151] As of October 2023[update], Earth has two confirmed Trojans:[152] (706765) 2010 TK7 and (614689) 2020 XL5, both circling Earth's L4 point.[153][154]

- Horseshoe librators: The region of stability around L4 and L5 also includes orbits for co-orbital asteroids that run around both L4 and L5. Relative to the Earth and Sun, the orbit can resemble the circumference of a horseshoe, or may consist of annual loops that wander back and forth (librate) in a horseshoe-shaped area. In both cases, the Sun is at the horseshoe's center of gravity, Earth is in the gap of the horseshoe, and L4 and L5 are inside the ends of the horseshoe. Among Earth's known co-orbitals, those with the most stable orbits as well as those with the least stable orbits are horseshoe librators.[151] As of October 2023[update], at least 13 horseshoe librators of Earth have been discovered.[152] The most-studied and, at about 5 km (3.1 mi), largest is 3753 Cruithne, which travels along bean-shaped annual loops and completes its horseshoe libration cycle every 770–780 years.[155][156] (419624) 2010 SO16 is an asteroid on a relatively stable circumference-of-a-horseshoe orbit, with a horseshoe libration period of about 350 years.[157]

- Quasi-satellites: Quasi-satellites are co-orbital asteroids on a normal elliptic orbit with a higher eccentricity than Earth's, which they travel in a way synchronised with Earth's motion. Since the asteroid orbits the Sun slower than Earth when further away and faster than Earth when closer to the Sun, when observed in a rotating frame of reference fixed to the Sun and the Earth, the quasi-satellite appears to orbit Earth in a retrograde direction in one year, even though it is not bound gravitationally. As of October 2023[update], six asteroids were known to be a quasi-satellite of Earth.[152] 469219 Kamoʻoalewa is Earth's closest quasi-satellite, in an orbit that has been stable for almost a century.[158] This asteroid is thought to be a piece of the Moon ejected during an impact.[152][159] Orbit calculations show that almost all quasi-satellites and many horseshoe librators repeatedly transfer between horseshoe and quasi-satellite orbits.[158][160] One of these objects, 2003 YN107, was observed during its transition from a quasi-satellite orbit to a horseshoe orbit in 2006; it is expected to transfer back to a quasi-satellite orbit sometime around year 2066.[161] A quasi-satellite discovered in 2023 but then found in old photographs back to 2012, 2023 FW13, was found to have an orbit that is stable for about 4,000 years, from 100 BC to AD 3700.[162]

- Asteroids on compound orbits: orbital calculations show that some co-orbital asteroids transit between horseshoe and quasi-satellite orbits during every horseshoe resp. quasi-satellite cycle. Theoretically, similar continuous transitions between Trojan and horseshoe orbits are possible, too. As of January 2023[update], at least 20 Earth co-orbital NEAs are thought to be in the horseshoe-like phase of compound orbits.[160]

2020 CD3 · Moon · Earth

- Temporary satellites: NEAs can also transfer between solar orbits and distant Earth orbits, becoming gravitationally bound temporary satellites. According to simulations, temporary satellites are typically caught when they pass Earth's L1 or L2 Lagrangian points at the time Earth is either at the point in its orbit closest or farthest from the Sun, complete a couple of orbits around Earth, and then return to a heliocentric orbit due to perturbations from the Moon.[29] Strictly speaking, temporary satellites aren't co-orbital asteroids, and they can have orbits of the broader Arjuna type before and after capture by Earth, but simulations show that they can be captured from, or transfer to, horseshoe orbits.[150] The simulations also indicate that Earth typically has at least one temporary satellite 1 m (3.3 ft) across at any given time, but they are too faint to be detected by current surveys.[29] As of December 2024[update], five temporary satellites have been observed:[150] 1991 VG,[163] 2006 RH120, 2020 CD3,[164][165] 2022 NX1[150] and 2024 PT5.[166] Calculations for the 5 m (16 ft) asteroid 2023 FY3 showed repeated transitions into temporary satellite orbits both in the past and the future 10,000 years.[150]

Near-Earth asteroids also include the co-orbitals of Venus. As of January 2023[update], all known co-orbitals of Venus have orbits with high eccentricity, also crossing Earth's orbit.[160][167]

Meteoroids

[edit]In 1961, the IAU defined meteoroids as a class of solid interplanetary objects distinct from asteroids by their considerably smaller size.[68] This definition was useful at the time because, with the exception of the Tunguska event, all historically observed meteors were produced by objects significantly smaller than the smallest asteroids then observable by telescopes.[68] As the distinction began to blur with the discovery of ever smaller asteroids and a greater variety of observed NEO impacts, revised definitions with size limits have been proposed from the 1990s.[68] In April 2017, the IAU adopted a revised definition that generally limits meteoroids to a size between 30 μm and 1 m in diameter, but permits the use of the term for any object of any size that caused a meteor, thus leaving the distinction between asteroid and meteoroid blurred.[168]

Near-Earth comets

[edit]

Near-Earth comets (NECs) are objects in a near-Earth orbit with a tail or coma made up of dust, gas or ionized particles emitted by a solid nucleus. Comet nuclei are typically less dense than asteroids but they pass Earth at higher relative speeds, thus the impact energy of a comet nucleus is slightly larger than that of a similar-sized asteroid.[170] NECs may pose an additional hazard due to fragmentation: the meteoroid streams which produce meteor showers may include large inactive fragments, effectively NEAs.[171] Although no impact of a comet in Earth's history has been conclusively confirmed, the Tunguska event may have been caused by a fragment of Comet Encke.[172]

Comets are commonly divided between short-period and long-period comets. Short-period comets, with an orbital period of less than 200 years, originate in the Kuiper belt, beyond the orbit of Neptune; while long-period comets originate in the Oort Cloud, in the outer reaches of the Solar System.[13] The orbital period distinction is of importance in the evaluation of the risk from near-Earth comets because short-period NECs are likely to have been observed during multiple apparitions and thus their orbits can be determined with some precision, while long-period NECs can be assumed to have been seen for the first and last time when they appeared since the start of precise observations, thus their approaches cannot be predicted well in advance.[13] Since the threat from long-period NECs is estimated to be at most 1% of the threat from NEAs, and long-period comets are very faint and thus difficult to detect at large distances from the Sun, Spaceguard efforts have consistently focused on asteroids and short-period comets.[104][170] Both NASA's CNEOS[2] and ESA's NEOCC[26] restrict their definition of NECs to short-period comets. As of December 30, 2024[update], 123 such objects have been discovered.[1]

Comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle, which is also the source of the Perseid meteor shower every year in August, has a roughly 130-year orbit that passes close to the Earth. During the comet's September 1992 recovery, when only the two previous returns in 1862 and 1737 had been identified, calculations showed that the comet would pass close to Earth during its next return in 2126, with an impact within the range of uncertainty. By 1993, even earlier returns (back to at least 188 AD) had been identified, and the longer observation arc eliminated the impact risk. The comet will pass Earth in 2126 at a distance of 23 million kilometers. In 3044, the comet is expected to pass Earth at less than 1.6 million kilometers.[173]

Artificial near-Earth objects

[edit]

Defunct space probes and final stages of rockets can end up in near-Earth orbits around the Sun. Examples of such artificial near-Earth objects include a Tesla Roadster used as dummy payload in a 2018 rocket test[174] and the Kepler space telescope.[175] Some of these objects have been re-discovered by NEO surveys when they returned to Earth's vicinity and classified as asteroids before their artificial origin was recognised.

An object classified as asteroid 1991 VG was discovered during its transition from a temporary satellite orbit around Earth to a solar orbit in November 1991, and could only be observed until April 1992. Some scientists suspected it to be a returning piece of man-made space debris. After new observations in 2017 provided better data on its orbit and surface characteristics, a new study found the artificial origin unlikely.[163]

In September 2002, astronomers found an object designated J002E3. The object was on a temporary satellite orbit around Earth, leaving for a solar orbit in June 2003. Calculations showed that it was also on a solar orbit before 2002, but was close to Earth in 1971. J002E3 was identified as the third stage of the Saturn V rocket that carried Apollo 12 to the Moon.[176][177] In 2006, two more apparent temporary satellites were discovered which were suspected of being artificial.[177] One of them was eventually confirmed as an asteroid and classified as the temporary satellite 2006 RH120.[177] The other, 6Q0B44E, was confirmed as an artificial object, but its identity is unknown.[177] Another temporary satellite was discovered in 2013, and was designated 2013 QW1 as a suspected asteroid. It was later found to be an artificial object of unknown origin. 2013 QW1 is no longer listed as an asteroid by the Minor Planet Center.[177][178] In September 2020, an object detected on an orbit very similar to that of the Earth was temporarily designated 2020 SO. However, orbital calculations and spectral observations confirmed that the object was the Centaur rocket booster of the 1966 Surveyor 2 uncrewed lunar lander.[179][180]

In some cases, active space probes on solar orbits have been observed by NEO surveys and erroneously catalogued as asteroids before identification. During its 2007 flyby of Earth on its route to a comet, ESA's space probe Rosetta was detected unidentified and classified as asteroid 2007 VN84, with an alert issued due to its close approach.[181] The designation 2015 HP116 was similarly removed from asteroid catalogues when the observed object was identified with Gaia, ESA's space observatory for astrometry.[182]

Exploratory missions

[edit]Some NEOs are of special interest because the sum total of changes in orbital speed required to send a spacecraft on a mission to physically explore an NEO – and thus the amount of rocket fuel required for the mission – is lower than what is necessary for even lunar missions, due to their combination of low velocity with respect to Earth and weak gravity. They may present interesting scientific opportunities both for direct geochemical and astronomical investigation, and as potentially economical sources of extraterrestrial materials for human exploitation.[11] This makes them an attractive target for exploration.[183]

Missions to NEAs

[edit]

The IAU held a minor planets workshop in Tucson, Arizona, in March 1971. At that point, launching a spacecraft to asteroids was considered premature; the workshop only inspired the first astronomical survey specifically aiming for NEAs.[12] Missions to asteroids were considered again during a workshop at the University of Chicago held by NASA's Office of Space Science in January 1978. Of all of the near-Earth asteroids (NEA) that had been discovered by mid-1977, it was estimated that spacecraft could rendezvous with and return from only about 1 in 10 using less propulsive energy than is necessary to reach Mars. It was recognised that due to the low surface gravity of all NEAs, moving around on the surface of an NEA would cost very little energy, and thus space probes could gather multiple samples.[12] Overall, it was estimated that about one percent of all NEAs might provide opportunities for human-crewed missions, or no more than about ten NEAs known at the time. A five-fold increase in the NEA discovery rate was deemed necessary to make a crewed mission within ten years worthwhile.[12]

The first near-Earth asteroid to be visited by a spacecraft was 433 Eros when NASA's NEAR Shoemaker probe orbited it from February 2000, landing on the surface of the 17 km (11 mi) asteroid in February 2001.[16] A second NEA, the 535 m (1,755 ft) long peanut-shaped 25143 Itokawa, was explored from September 2005 to April 2007 by JAXA's Hayabusa mission, which succeeded in taking material samples back to Earth.[184] A third NEA, the 2.26 km (1.40 mi) long elongated 4179 Toutatis, was explored by CNSA's Chang'e 2 spacecraft during a flyby in December 2012.[17][25]

The 980 m (3,220 ft) Apollo asteroid 162173 Ryugu was explored from June 2018[185] until November 2019[18] by JAXA's Hayabusa2 space probe, which returned a sample to Earth.[21] A second sample-return mission, NASA's OSIRIS-REx probe, targeted the 500 m (1,600 ft) Apollo asteroid 101955 Bennu,[186] which, as of January 2025[update], has the third-highest cumulative Palermo scale rating (−1.40 for several close encounters between 2178 and 2290).[83] On its journey to Bennu, the probe had searched unsuccessfully for Earth's Trojan asteroids,[187] entered into orbit around Bennu in December 2018, touched down on its surface in October 2020,[19] and was successful in returning samples to Earth three years later.[22] China launched its own sample-return mission, Tianwen-2, in May 2025, targeting Earth quasi-satellite 469219 Kamoʻoalewa and returning samples to Earth in late 2027.[188]

After completing its mission to Bennu, the probe OSIRIS-REx was redirected towards 99942 Apophis, which it is planned to orbit from April 2029.[19] After completing its exploration of 162173 Ryugu, the mission of the Hayabusa2 space probe was extended, to include flybys of S-type Apollo asteroid 98943 Torifune in July 2026 and fast-rotating Apollo asteroid 1998 KY26 in July 2031.[189] In 2025, JAXA plans to launch another probe, DESTINY+, to explore Apollo asteroid 3200 Phaethon, the parent body of the Geminid meteor shower, during a flyby.[190]

Asteroid deflection tests

[edit]

On September 26, 2022, NASA's DART spacecraft reached the system of 65803 Didymos and impacted the Apollo asteroid's moon Dimorphos, in a test of a method of planetary defense against near-Earth objects.[20] In addition to telescopes on or in orbit around the Earth, the impact was observed by the Italian mini-spacecraft or CubeSat LICIACube, which separated from DART 15 days before impact.[20] The impact shortened the orbital period of Dimorphos around Didymos by 33 minutes, indicating that the moon's momentum change was 3.6 times the momentum of the impacting spacecraft, thus most of the change was due to the ejected material of the moon itself.[23]

In October 2024, ESA launched the spacecraft Hera, which is to enter orbit around Didymos in December 2026, to study the consequences of the DART impact.[191] China plans to launch its own pair of asteroid deflection and observation probes in 2027, which are to target 30 m (98 ft) Aten asteroid 2015 XF261.[192]

Space mining

[edit]From the 2000s, there were plans for the commercial exploitation of near-Earth asteroids, either through the use of robots or even by sending private commercial astronauts to act as space miners, but few of these plans were pursued.[24]

In April 2012, the company Planetary Resources announced its plans to mine asteroids commercially. In a first phase, the company reviewed data and selected potential targets among NEAs. In a second phase, space probes would be sent to the selected NEAs; mining spacecraft would be sent in a third phase.[193] Planetary Resources launched two testbed satellites in April 2015[194] and January 2018,[195] and the first prospecting satellite for the second phase was planned for a 2020 launch prior to the company closing and its assets purchased by ConsenSys Space in 2018.[194][196]

Another American company established with the goal of space mining, AstroForge, launched the probe Odin (formerly Brokkr-2) on February 26, 2025, to perform a flyby of asteroid 2022 OB5, but the probe showed technical problems.[197] The goal of the mission was to confirm if 2022 OB5 is a metal-rich M-type asteroid.[198] Regardless of the success of Odin, AstroForge plans to follow it up a year later with the probe Vestri, which is to land on the same asteroid.[197]

Missions to NECs

[edit]

The first near-Earth comet visited by a space probe was 21P/Giacobini–Zinner in 1985, when the NASA/ESA probe International Cometary Explorer (ICE) passed through its coma. In March 1986, ICE, along with Soviet probes Vega 1 and Vega 2, ISAS probes Sakigake and Suisei and ESA probe Giotto flew by the nucleus of Halley's Comet. In 1992, Giotto also visited another NEC, 26P/Grigg–Skjellerup.[13]

In November 2010, after completing its primary mission to non-near-Earth comet Tempel 1, the NASA probe Deep Impact flew by the near-Earth comet 103P/Hartley.[14]

In August 2014, ESA probe Rosetta began orbiting near-Earth comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, while its lander Philae landed on its surface in November 2014. After the end of its mission, Rosetta was crashed into the comet's surface in 2016.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Discovery Statistics – Cumulative Totals". NASA/JPL CNEOS. December 30, 2024. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "NEO Basics. NEO Groups". NASA/JPL CNEOS. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Chapman, Clark R. (May 2004). "The hazard of near-Earth asteroid impacts on earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 222 (1): 1–15. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.222....1C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.03.004.

- ^ Monastersky, Richard (March 1, 1997). "The Call of Catastrophes". Science News Online. Archived from the original on March 13, 2004. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Rumpf, Clemens M.; Lewis, Hugh G.; Atkinson, Peter M. (March 23, 2017). "Asteroid impact effects and their immediate hazards for human populations". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (8): 3433–3440. arXiv:1703.07592. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.3433R. doi:10.1002/2017gl073191. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 34867206.

- ^ a b c d e f Fernández Carril, Luis (May 14, 2012). "The evolution of near Earth objects risk perception". The Space Review. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c "NASA on the Prowl for Near-Earth Objects". NASA/JPL. May 26, 2004. Archived from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c "WISE Revises Numbers of Asteroids Near Earth". NASA/JPL. September 29, 2011. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b "Public Law 109–155–DEC.30, 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Templeton, Graham (January 12, 2016). "NASA is opening a new office for planetary defense". ExtremeTech. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Vergano, Dan (February 2, 2007). "Near-Earth asteroids could be 'steppingstones to Mars'". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Portree, David S. (March 23, 2013). "Earth-Approaching Asteroids as Targets for Exploration (1978)". Wired. Archived from the original on June 1, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

People in the early 21st century have been encouraged to see asteroids as the interplanetary equivalent of sea monsters. We often hear talk of "killer asteroids," when in fact there exists no conclusive evidence that any asteroid has killed anyone in all of human history. ... In the 1970s, asteroids had yet to gain their present fearsome reputation ... most astronomers and planetary scientists who made a career of studying asteroids rightfully saw them as sources of fascination, not of worry.

- ^ a b c d e f Report of the Task Force on potentially hazardous Near Earth Objects (PDF). London: British National Space Centre. September 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Beatty, Kelly (November 4, 2010). "Mr. Hartley's Amazing Comet". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Aron, Jacob (September 30, 2016). "Rosetta lands on 67P in grand finale to two year comet mission". New Scientist. Archived from the original on December 3, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Savage, Donald & Buckley, Michael (January 31, 2001). "NEAR Mission Completes Main Task, Now Will Go Where No Spacecraft Has Gone Before". Press Releases. NASA. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Lakdawalla, Emily (December 14, 2012). "Chang'e 2 imaging of Toutatis". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on December 3, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Bartels, Meghan (November 13, 2019). "Farewell, Ryugu! Japan's Hayabusa2 Probe Leaves Asteroid for Journey Home". Space.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c Taylor Tillman, Nola (September 25, 2023). "OSIRIS-REx: A complete guide to the asteroid-sampling mission". Space.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Bardan, Roxana (September 27, 2022). "NASA's DART Mission Hits Asteroid in First-Ever Planetary Defense Test". Press Releases. NASA. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Rincon, Paul (December 6, 2020). "Hayabusa-2: Capsule with asteroid samples in 'perfect' shape". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on October 24, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Loeffer, John (January 23, 2024). "NASA finally opens OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample canister after freeing stuck lid". Space.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Merzdorf, Jessica (December 15, 2022). "Early Results from NASA's DART Mission". Press Releases. NASA. Archived from the original on January 2, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b Dorminey, Bruce (August 31, 2021). "Does Commercial Asteroid Mining Still Have A Future?". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 4, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Near Earth Objects". IAU. Archived from the original on December 17, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Definitions & Assumptions". ESA NEOCC. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Morbidelli, Alessandro; Bottke, William F. Jr.; Froeschlé, Christiane; Michel, Patrick (January 2002). "Origin and Evolution of Near-Earth Objects". In Bottke Jr., W. F.; et al. (eds.). Asteroids III (PDF). pp. 409–422. Bibcode:2002aste.book..409M. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1v7zdn4.33. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Waszczak, Adam; Prince, Thomas A.; et al. (2017). "Small Near-Earth Asteroids in the Palomar Transient Factory Survey: A Real-Time Streak-detection System". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 129 (973). part 034402. arXiv:1609.08018. Bibcode:2017PASP..129c4402W. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/129/973/034402. ISSN 1538-3873. S2CID 43606524.

- ^ a b c Carlisle, Camille M. (December 30, 2011). "Pseudo-moons orbit Earth". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on May 30, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c "List Of Potentially Hazardous Minor Planets (by designation)". IAU/MPC. Archived from the original on January 2, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Perna, D.; Barucci, M. A.; Fulchignoni, M. (2013). "The near-Earth objects and their potential threat to our planet". The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review. 21 (1): 65. Bibcode:2013A&ARv..21...65P. doi:10.1007/s00159-013-0065-4.

- ^ Halley, Edmund (1705). A synopsis of the astronomy of comets. London: John Senex. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Stoyan, Ronald (2015). Atlas of Great Comets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-1-107-09349-2. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Dick, S. J. (June 1998). "Observation and interpretation of the Leonid meteors over the last millennium". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 1 (1): 1–20. Bibcode:1998JAHH....1....1D. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.1998.01.01.

- ^ Scholl, Hans; Schmadel, Lutz D. (2002). "Discovery Circumstances of the First Near-Earth Asteroid (433) Eros". Acta Historica Astronomiae. 15: 210–220. Bibcode:2002AcHA...15..210S.

- ^ "Eros comes on stage, finally a useful asteroid". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 3, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Closest Approaches to the Earth by Comets". IAU/MPC. May 16, 2019. Archived from the original on August 7, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ Sekanina, Zdenek; Chodas, Paul W. (December 2005). "Origin of the Marsden and Kracht Groups of Sunskirting Comets. I. Association with Comet 96P/Machholz and Its Interplanetary Complex". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 151 (2): 551–586. Bibcode:2005ApJS..161..551S. doi:10.1086/497374. S2CID 85442034.

- ^ "Small-Body Database Lookup. P/1999 J6 (SOHO)". NASA/JPL. April 16, 2021. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b "Radar observations of long-lost asteroid 1937 UB (Hermes)". UCLA. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Small-Body Database Lookup. 1566 Icarus (1949 MA)". NASA/JPL. August 4, 2024. Archived from the original on January 3, 2025. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Pettengill, G. H.; Shapiro, I. I.; Ash, M. E.; Ingalls, R. P.; Rainville, L. P.; Smith, W. B.; et al. (May 1969). "Radar observations of Icarus". Icarus. 10 (3): 432–435. Bibcode:1969Icar...10..432P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(69)90101-8. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Goldstein, R. M. (November 1968). "Radar Observations of Icarus". Science. 162 (3856): 903–904. Bibcode:1968Sci...162..903G. doi:10.1126/science.162.3856.903. PMID 17769079. S2CID 129644095.

- ^ a b c Marsden, Brian G. (March 29, 1998). "How the Asteroid Story Hit: An Astronomer Reveals How a Discovery Spun Out of Control". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Scotti, J. V.; Rabinowitz, D. L.; Marsden, B. G. (November 28, 1991). "Near miss of the Earth by a small asteroid". Nature. 354 (6351): 287–289. Bibcode:1991Natur.354..287S. doi:10.1038/354287a0.

- ^ a b "Closest Approaches to the Earth by Minor Planets". IAU/MPC. May 16, 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "NEO Earth Close Approaches". NASA/JPL CNEOS. January 2, 2025. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ Irizarry, Eddie (November 16, 2020). "This asteroid just skimmed Earth's atmosphere". EarthSky. Archived from the original on December 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Small-Body Database Lookup. 308635 (2005 YU55)". NASA/JPL. January 7, 2022. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Palmer, Jason (February 15, 2013). "Asteroid 2012 DA14 in record-breaking Earth pass". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Chodas, Paul; Giorgini, Jon & Yeomans, Don (March 6, 2012). "Near-Earth Asteroid 2012 DA14 to Miss Earth on February 15, 2013". News. NASA/JPL CNEOS. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Aeroplane-sized asteroids approaching earth fast. Check details from NASA". The Indian Express. 2025-10-09. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ "Grand Teton Meteor (video)". YouTube. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Ceplecha, Z. (March 1994). "Earth-grazing daylight fireball of August 10, 1972". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 283 (1): 287−288. Bibcode:1994A&A...283..287C.

- ^ Borovička, J.; Ceplecha, Z. (April 1992). "Earth-grazing fireball of October 13, 1990". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 257 (1): 323–328. Bibcode:1992A&A...257..323B. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Chapman, Clark R. & Morrison, David (January 6, 1994). "Impacts on the Earth by asteroids and comets: Assessing the hazard" (PDF). Nature. 367 (6458): 33–40. Bibcode:1994Natur.367...33C. doi:10.1038/367033a0. S2CID 4305299. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Collins, Gareth S.; Melosh, H. Jay; Marcus, Robert A. (June 2005). "Earth Impact Effects Program: A Web-based computer program for calculating the regional environmental consequences of a meteoroid impact on Earth" (PDF). Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 40 (6): 817–840. Bibcode:2005M&PS...40..817C. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2005.tb00157.x. hdl:10044/1/11554. S2CID 13891988. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c Asher, D. J.; Bailey, M.; Emelʹyanenko, V.; Napier, W. (October 2005). "Earth in the Cosmic Shooting Gallery". The Observatory. 125 (2): 319–322. Bibcode:2005Obs...125..319A.

- ^ Marcus, Robert; Melosh, H. Jay & Collins, Gareth (2010). "Earth Impact Effects Program". Imperial College London / Purdue University. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025. (solution using 2600 kg/m^3, 17 km/s, 45 degrees)

- ^ a b David, Leonard (November 1, 2013). "Russian fireball explosion shows meteor risk greater than thought". Space.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Silber, Elizabeth A.; Revelle, Douglas O.; Brown, Peter G.; Edwards, Wayne N. (2009). "An estimate of the terrestrial influx of large meteoroids from infrasonic measurements". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (E8). Bibcode:2009JGRE..114.8006S. doi:10.1029/2009JE003334.

- ^ Allen, Robert S. (1963). "Antarctic Explosion Could Have Been Nuclear Detonation". The San Bernardino Sun (4 December). p. 40 col. f.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R. (September 1, 2014). "Reconstructing the Chelyabinsk event: Pre-impact orbital evolution". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443 (1): L39 – L43. arXiv:1405.7202. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..39D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu078. S2CID 118417667.

- ^ Shaddad, Muawia H.; et al. (October 2010). "The recovery of asteroid 2008 TC3". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 45 (10–11): 1557–1589. Bibcode:2010M&PS...45.1557S. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2010.01116.x.

- ^ Tingley, Brett (December 3, 2024). "Tiny asteroid detected hours before hitting Earth to become 4th 'imminent impactor' of 2024". Space.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2024. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Beatty, Kelly (January 2, 2014). "Small asteroid 2014 AA hits Earth". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on July 25, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "Fireballs. Fireball and Bolide Data". NASA/JPL. December 20, 2024. Archived from the original on January 1, 2025. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Rubin, Alan E.; Grossman, Jeffrey N. (January 2010). "Meteorite and meteoroid: New comprehensive definitions". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 45 (1): 114–122. Bibcode:2010M&PS...45..114R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2009.01009.x. S2CID 129972426.

- ^ a b "Lunar Impact Monitoring Program". NASA. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Rubio, Luis R. Bellot; Ortiz, Jose L.; Sada, Pedro V. (2000). "Observation and Interpretation of Meteoroid Impact Flashes on the Moon". In Jenniskens, P.; et al. (eds.). Leonid Storm Research. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 575–598. Bibcode:2000lsr..book..575B. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2071-7_42. ISBN 978-90-481-5624-5. S2CID 118392496.

- ^ a b Catanzaro, Michele (February 24, 2014). "Largest lunar impact caught by astronomers". Nature. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "About the NELIOTA project". ESA. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "MIDAS: Moon Impacts Detection and Analysis System. Main Results". Meteoroides.NET. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Clark, Stuart (December 20, 2012). "Apocalypse postponed: how Earth survived Halley's comet in 1910". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2025.