Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Voyager 2

View on Wikipedia

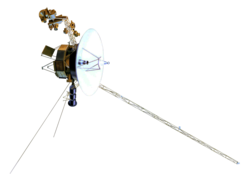

Artist's rendering of the Voyager spacecraft design | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mission type | Planetary exploration | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 1977-076A[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 10271[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | science | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mission duration |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 721.9 kilograms (1,592 lb)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Power | 470 watts (at launch) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch date | August 20, 1977, 14:29:00 UTC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rocket | Titan IIIE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Jupiter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | July 9, 1979 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 570,000 kilometers (350,000 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Saturn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | August 26, 1981 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 101,000 km (63,000 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Uranus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | January 24, 1986 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 81,500 km (50,600 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flyby of Neptune | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closest approach | August 25, 1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 4,951 km (3,076 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Large Strategic Science Missions Planetary Science Division | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Plot 1 is viewed from the north ecliptic pole, to scale.

Plots 2 to 4 are third-angle projections at 20% scale.

In the SVG file, hover over a trajectory or orbit to highlight it and its associated launches and flybys.

Voyager 2 is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, as a part of the Voyager program. It was launched on a trajectory towards the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and enabled further encounters with the ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). The only spacecraft to have visited either of the ice giant planets, it was the third of five spacecraft to achieve Solar escape velocity, which allowed it to leave the Solar System. Launched 16 days before its twin Voyager 1, the primary mission of the spacecraft was to study the outer planets and its extended mission is to study interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere.

Voyager 2 successfully fulfilled its primary mission of visiting the Jovian system in 1979, the Saturnian system in 1981, Uranian system in 1986, and the Neptunian system in 1989. The spacecraft is in its extended mission of studying the interstellar medium. It is at a distance of 139.26 AU (20.8 billion km; 12.9 billion mi) from Earth as of May 2025[update].[4]

The probe entered the interstellar medium on November 5, 2018, at a distance of 119.7 AU (11.1 billion mi; 17.9 billion km) from the Sun[5] and moving at a velocity of 15.341 km/s (34,320 mph)[4] relative to the Sun. Voyager 2 has left the Sun's heliosphere and is traveling through the interstellar medium, though still inside the Solar System, joining Voyager 1, which had reached the interstellar medium in 2012.[6][7][8][9] Voyager 2 has begun to provide the first direct measurements of the density and temperature of the interstellar plasma.[10]

Voyager 2 is in contact with Earth through the NASA Deep Space Network.[11] Communications are the responsibility of Australia's DSS 43 communication antenna, near Canberra.[12]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]In the early space age, it was realized that a periodic alignment of the outer planets would occur in the late 1970s and enable a single probe to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune by taking advantage of the then-new technique of gravity assists. NASA began work on a Grand Tour, which evolved into a massive project involving two groups of two probes each, with one group visiting Jupiter, Saturn, and Pluto and the other Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. The spacecraft would be designed with redundant systems to ensure survival throughout the entire tour. By 1972 the mission was scaled back and replaced with two Mariner program-derived spacecraft, the Mariner Jupiter-Saturn probes. To keep apparent lifetime program costs low, the mission would include only flybys of Jupiter and Saturn, but keep the Grand Tour option open.[13]: 263 As the program progressed, the name was changed to Voyager.[14]

The primary mission of Voyager 1 was to explore Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Voyager 2 was also to explore Jupiter and Saturn, but on a trajectory that would have the option of continuing on to Uranus and Neptune, or being redirected to Titan as a backup for Voyager 1. Upon successful completion of Voyager 1's objectives, Voyager 2 would get a mission extension to send the probe on towards Uranus and Neptune.[13] Titan was selected due to the interest developed after the images taken by Pioneer 11 in 1979, which had indicated the atmosphere of the moon was substantial and complex. Hence the trajectory was designed for optimum Titan flyby.[15][16]

Spacecraft design

[edit]Constructed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Voyager 2, whose bus is shaped like a decagonal prism, included 16 hydrazine thrusters, three-axis stabilization, gyroscopes and celestial referencing instruments (a Sun sensor, and a Canopus star tracker) to maintain pointing of the high-gain antenna toward Earth. Collectively these instruments are part of the Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem (AACS) along with redundant units of most instruments and 8 backup thrusters. The spacecraft also included 11 scientific instruments to study celestial objects as it traveled through space.[17]

Communications

[edit]Built with the intent for eventual interstellar travel, Voyager 2 included a large, 3.7 m (12 ft) parabolic, high-gain antenna (see diagram) to transceive data via the Deep Space Network on Earth. Communications are conducted over the S-band (about 13 cm wavelength) and X-band (about 3.6 cm wavelength) providing data rates as high as 115.2 kilobits per second at the distance of Jupiter, and then ever-decreasing as distance increases, because of the inverse-square law.[18] When the spacecraft is unable to communicate with Earth, the Digital Tape Recorder (DTR) can record about 64 megabytes of data for transmission at another time.[19]

Power

[edit]

Voyager 2 is equipped with three multihundred-watt radioisotope thermoelectric generators (MHW RTGs). Each RTG includes 24 pressed plutonium oxide spheres. At launch, each RTG provided enough heat to generate approximately 157 W of electrical power. Collectively, the RTGs supplied the spacecraft with 470 watts at launch (halving every 87.7 years). They were predicted to allow operations to continue until at least 2020, and continued to provide power to five scientific instruments through the early part of 2023. In April 2023 JPL began using a reservoir of backup power intended for an onboard safety mechanism. As a result, all five instruments had been expected to continue operation through 2026.[17][2][20][21] In October 2024 NASA announced that the plasma science instrument had been turned off, preserving power for the remaining four instruments.[22]

Attitude control and propulsion

[edit]Because of the energy required to achieve a Jupiter trajectory boost with an 825-kilogram (1,819 lb) payload, the spacecraft included a propulsion module made of a 1,123-kilogram (2,476 lb) solid-rocket motor and eight hydrazine monopropellant rocket engines, four providing pitch and yaw attitude control, and four for roll control. The propulsion module was jettisoned shortly after the successful Jupiter burn.

Sixteen hydrazine Aerojet MR-103 thrusters on the mission module provide attitude control.[23] Four are used to execute trajectory correction maneuvers; the others in two redundant six-thruster branches, to stabilize the spacecraft on its three axes. Only one branch of attitude control thrusters is needed at any time.[24]

Thrusters are supplied by a single 70-centimeter (28 in) diameter spherical titanium tank. It contained 100 kilograms (220 lb) of hydrazine at launch, providing enough fuel until 2034.[25]

Scientific instruments

[edit]| Instrument name | Abr. | Description | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Science System (disabled) |

(ISS) | Utilized a two-camera system (narrow-angle/wide-angle) to provide imagery of the outer planets and other objects along the trajectory.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Radio Science System (disabled) |

(RSS) | Utilized the telecommunications system of the Voyager spacecraft to determine the physical properties of planets and satellites (ionospheres, atmospheres, masses, gravity fields, densities) and the amount and size distribution of material in Saturn's rings and the ring dimensions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infrared interferometer spectrometer and radiometer (disabled) |

(IRIS) | Investigates both global and local energy balance and atmospheric composition. Vertical temperature profiles are also obtained from the planets and satellites as well as the composition, thermal properties, and size of particles in Saturn's rings. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ultraviolet Spectrometer (disabled) |

(UVS) | Designed to measure atmospheric properties, and to measure radiation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer (active) |

(MAG) | Designed to investigate the magnetic fields of Jupiter and Saturn, the solar-wind interaction with the magnetospheres of these planets, and the interplanetary magnetic field out to the solar wind boundary with the interstellar magnetic field and beyond, if crossed. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plasma Spectrometer (disabled) |

(PLS) | Investigates the macroscopic properties of the plasma ions and measures electrons in the energy range from 5 eV to 1 keV. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low Energy Charged Particle Instrument (disabled) |

(LECP) | Measures the differential in energy fluxes and angular distributions of ions, electrons and the differential in energy ion composition. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cosmic Ray System (active) |

(CRS) | Determines the origin and acceleration process, life history, and dynamic contribution of interstellar cosmic rays, the nucleosynthesis of elements in cosmic-ray sources, the behavior of cosmic rays in the interplanetary medium, and the trapped planetary energetic-particle environment. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Planetary Radio Astronomy Investigation (disabled) |

(PRA) | Utilizes a sweep-frequency radio receiver to study the radio-emission signals from Jupiter and Saturn.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Photopolarimeter System (defective) |

(PPS) | Utilized a telescope with a polarizer to gather information on surface texture and composition of Jupiter and Saturn and information on atmospheric scattering properties and density for both planets.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plasma Wave Subsystem (active) |

(PWS) | Provides continuous, sheath-independent measurements of the electron-density profiles at Jupiter and Saturn as well as basic information on local wave-particle interaction, useful in studying the magnetospheres.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Voyager in transport to a solar thermal test chamber.

-

Voyager 2 awaiting payload entry into a Titan IIIE/Centaur rocket.

Mission profile

[edit]-

Voyager 2's trajectory from the Earth, following the ecliptic through 1989 at Neptune and now heading south into the Pavo constellation

-

Path viewed from above the Solar System

-

Path viewed from side, showing distance below ecliptic in gray

| Timeline of travel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Event | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1977-08-20 | Spacecraft launched at 14:29:00 UTC. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1977-12-10 | Entered asteroid belt. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1977-12-19 | Voyager 1 overtakes Voyager 2. (see diagram) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1978-06 | Primary radio receiver fails. The remainder of the mission flown using backup. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1978-10-21 | Exited asteroid belt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1979-04-25 | Start Jupiter observation phase

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1981-06-05 | Start Saturn observation phase.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1985-11-04 | Start Uranus observation phase.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1989-06-05 | Start Neptune observation phase.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1989-10-02 | Begin Voyager Interstellar Mission. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interstellar phase[28][29][30] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1998-11-13 | Terminate scan platform and UV observations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2007-09-06 | Terminate data tape recorder operations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2008-02-22 | Terminate planetary radio astronomy experiment operations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2011-11-07 | Switch to backup thrusters to conserve power[31] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018-11-05 | Crossed the heliopause and entered interstellar space. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2023-07-18 | Voyager 2 overtook Pioneer 10 as the second farthest spacecraft from the Sun.[32][33] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2024-10 | Turned off the plasma science instrument.[34] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2025-03-24 | Turned off the low-energy charged particle instrument.[35] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Launch and trajectory

[edit]The Voyager 2 probe was launched on August 20, 1977, by NASA from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard a Titan IIIE/Centaur launch vehicle. Two weeks later, the twin Voyager 1 probe was launched on September 5, 1977. However, Voyager 1 reached both Jupiter and Saturn sooner, as Voyager 2 had been launched into a longer, more circular trajectory.[36][37]

Voyager 1's initial orbit had an aphelion of 8.9 AU (830 million mi; 1.33 billion km), just a little short of Saturn's orbit of 9.5 AU (880 million mi; 1.42 billion km). Whereas, Voyager 2's initial orbit had an aphelion of 6.2 AU (580 million mi; 930 million km), well short of Saturn's orbit.[38]

In April 1978, no commands were transmitted to Voyager 2 for a period of time, causing the spacecraft to switch from its primary radio receiver to its backup receiver.[39] Sometime afterwards, the primary receiver failed altogether. The backup receiver was functional, but a failed capacitor in the receiver meant that it could only receive transmissions that were sent at a precise frequency, and this frequency would be affected by the Earth's rotation (due to the Doppler effect) and the onboard receiver's temperature, among other things.[40][41]

-

Voyager 2 launch on August 20, 1977, with a Titan IIIE/Centaur

-

Trajectory of Voyager 2 primary mission

-

Plot of Voyager 2's heliocentric velocity against its distance from the Sun, illustrating the use of gravity assists to accelerate the spacecraft by Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus.[A]

Encounter with Jupiter

[edit]

Voyager 2 · Jupiter · Io · Europa · Ganymede · Callisto

Voyager 2's closest approach to Jupiter occurred at 22:29 UT on July 9, 1979.[3] It came within 570,000 km (350,000 mi) of the planet's cloud tops.[43] Jupiter's Great Red Spot was revealed as a complex storm moving in a counterclockwise direction. Other smaller storms and eddies were found throughout the banded clouds.[44]

Voyager 2 returned images of Jupiter, as well as its moons Amalthea, Io, Callisto, Ganymede, and Europa.[3] During a 10-hour "volcano watch", it confirmed Voyager 1's observations of active volcanism on the moon Io, and revealed how the moon's surface had changed in the four months since the previous visit.[3] Together, the Voyagers observed the eruption of nine volcanoes on Io, and there is evidence that other eruptions occurred between the two Voyager fly-bys.[36]

Jupiter's moon Europa displayed a large number of intersecting linear features in the low-resolution photos from Voyager 1. At first, scientists believed the features might be deep cracks, caused by crustal rifting or tectonic processes. Closer high-resolution photos from Voyager 2, however, were puzzling: the features lacked topographic relief, and one scientist said they "might have been painted on with a felt marker".[36] Europa is internally active due to tidal heating at a level about one-tenth that of Io. Europa is thought to have a thin crust (less than 30 km (19 mi) thick) of water ice, possibly floating on a 50 km (31 mi)-deep ocean.[36][37]

Two new, small satellites, Adrastea and Metis, were found orbiting just outside the ring.[36] A third new satellite, Thebe, was discovered between the orbits of Amalthea and Io.[36]

Encounter with Saturn

[edit]The closest approach to Saturn occurred at 03:24:05 UT on August 26, 1981.[45] When Voyager 2 passed behind Saturn, viewed from Earth, it utilized its radio link to investigate Saturn's upper atmosphere, gathering data on both temperature and pressure. In the highest regions of the atmosphere, where the pressure was measured at 70 mbar (1.0 psi),[46] Voyager 2 recorded a temperature of 82 K (−191.2 °C; −312.1 °F). Deeper within the atmosphere, where the pressure was recorded to be 1,200 mbar (17 psi), the temperature rose to 143 K (−130 °C; −202 °F).[47] The spacecraft also observed that the north pole was approximately 10 °C (18 °F) cooler at 100 mbar (1.5 psi) than mid-latitudes, a variance potentially attributable to seasonal shifts[47] (see also Saturn Oppositions).

After its Saturn fly-by, Voyager 2's scan platform experienced an anomaly causing its azimuth actuator to seize. This malfunction led to some data loss and posed challenges for the spacecraft's continued mission. The anomaly was traced back to a combination of issues, including a design flaw in the actuator shaft bearing and gear lubrication system, corrosion, and debris build-up. While overuse and depleted lubricant were factors,[48] other elements, such as dissimilar metal reactions and a lack of relief ports, compounded the problem. Engineers on the ground were able to issue a series of commands, rectifying the issue to a degree that allowed the scan platform to resume its function.[49] Voyager 2, which would have been diverted to perform the Titan flyby if Voyager 1 had been unable to, did not pass near Titan due to the malfunction, and subsequently, proceeded with its mission to explore the Uranian system.[50]: 94

-

Voyager 2 Saturn approach view

-

North, polar region of Saturn imaged in orange and UV filters

-

Atmosphere of Titan imaged from 2.3 million km

-

"Spoke" features observed in the rings of Saturn

Encounter with Uranus

[edit]The closest approach to Uranus occurred on January 24, 1986, when Voyager 2 came within 81,500 km (50,600 mi) of the planet's cloudtops.[51] Voyager 2 also discovered 11 previously unknown moons: Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalind, Belinda, Puck and Perdita.[B] The mission also studied the planet's unique atmosphere, caused by its axial tilt of 97.8°, and examined the Uranian ring system.[51] The length of a day on Uranus as measured by Voyager 2 is 17 hours, 14 minutes.[51] Uranus was shown to have a magnetic field that was misaligned with its rotational axis, unlike other planets that had been visited to that point,[52][55] and a helix-shaped magnetic tail stretching 10 million kilometers (6 million miles) away from the Sun.[52]

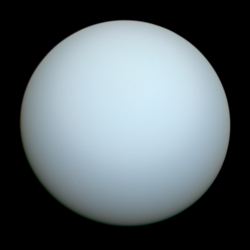

When Voyager 2 visited Uranus, much of its cloud features were hidden by a layer of haze; however, false-color and contrast-enhanced images show bands of concentric clouds around its south pole. This area was also found to radiate large amounts of ultraviolet light, a phenomenon that is called "dayglow". The average atmospheric temperature is about 60 K (−351.7 °F; −213.2 °C). The illuminated and dark poles, and most of the planet, exhibit nearly the same temperatures at the cloud tops.[52]

The Voyager 2 Planetary Radio Astronomy (PRA) experiment observed 140 lightning flashes, or Uranian electrostatic discharges with a frequency of 0.9-40 MHz.[56][57] The UEDs were detected from 600,000 km (370,000 mi) of Uranus over 24 hours, most of which were not visible.[56] However, microphysical modeling suggests that Uranian lightning occurs in convective storms occurring in deep troposphere water clouds.[56] If this is the case, lightning will not be visible due to the thick cloud layers above the troposphere.[57] Uranian lightning has a power of around 108 W, emits 1×10^7 J – 2×10^7 J of energy, and lasts an average of 120 ms.[57]

Detailed images from Voyager 2's flyby of the Uranian moon Miranda showed huge canyons made from geological faults.[52] One hypothesis suggests that Miranda might consist of a reaggregation of material following an earlier event when Miranda was shattered into pieces by a violent impact.[52]

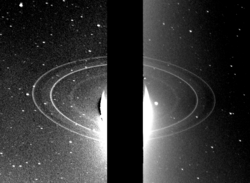

Voyager 2 discovered two previously unknown Uranian rings.[52][53] Measurements showed that the Uranian rings are different from those at Jupiter and Saturn. The Uranian ring system might be relatively young, and it did not form at the same time that Uranus did. The particles that make up the rings might be the remnants of a moon that was broken up by either a high-velocity impact or torn up by tidal effects.[36][37]

In March 2020, NASA astronomers reported the detection of a large atmospheric magnetic bubble, also known as a plasmoid, released into outer space from the planet Uranus, after reevaluating old data recorded during the flyby.[58][59]

-

Uranus as viewed by Voyager 2

-

Departing image of crescent Uranus

-

Ariel as imaged from 130,000 km

-

The rings of Uranus imaged by Voyager 2

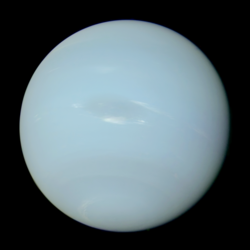

Encounter with Neptune

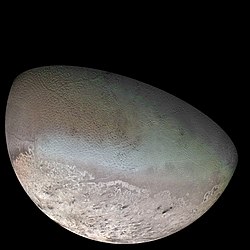

[edit]Following a course correction in 1987, Voyager 2's closest approach to Neptune occurred on August 25, 1989.[60][36] Through repeated computerized test simulations of trajectories through the Neptunian system conducted in advance, flight controllers determined the best way to route Voyager 2 through the Neptune–Triton system. Since the plane of the orbit of Triton is tilted significantly with respect to the plane of the ecliptic; through course corrections, Voyager 2 was directed into a path about 4,950 km (3,080 mi) above the north pole of Neptune.[61][62] Five hours after Voyager 2 made its closest approach to Neptune, it performed a close fly-by of Triton, Neptune's largest moon, passing within about 40,000 km (25,000 mi).[61]

In 1989, the Voyager 2 Planetary Radio Astronomy (PRA) experiment observed around 60 lightning flashes, or Neptunian electrostatic discharges emitting energies over 7×108 J.[63] A plasma wave system (PWS) detected 16 electromagnetic wave events with a frequency range of 50 Hz – 12 kHz at magnetic latitudes 7˚–33˚.[56][64] These plasma wave detections were possibly triggered by lightning over 20 minutes in the ammonia clouds of the magnetosphere.[64] During Voyager 2's closest approach to Neptune, the PWS instrument provided Neptune’s first plasma wave detections at a sample rate of 28,800 samples per second.[64] The measured plasma densities range from 10–3 – 10–1 cm–3.[64][65]

Voyager 2 discovered previously unknown Neptunian rings,[66] and confirmed six new moons: Despina, Galatea, Larissa, Proteus, Naiad and Thalassa.[67][C] While in the neighborhood of Neptune, Voyager 2 discovered the "Great Dark Spot", which has since disappeared, according to observations by the Hubble Space Telescope.[68] The Great Dark Spot was later hypothesized to be a region of clear gas, forming a window in the planet's high-altitude methane cloud deck.[69]

-

Voyager 2 image of Neptune

-

Cirrus clouds imaged above gaseous Neptune

-

Rings of Neptune taken in occultation from 280,000 km

-

Color mosaic of Voyager 2 Triton

Interstellar mission

[edit]

Once its planetary mission was over, Voyager 2 was described as working on an interstellar mission, which NASA is using to find out what the Solar System is like beyond the heliosphere. As of September 2023[update] Voyager 2 is transmitting scientific data at about 160 bits per second.[70] Information about continuing telemetry exchanges with Voyager 2 is available from Voyager Weekly Reports.[71]

In 1992, Voyager 2 observed the nova V1974 Cygni in the far-ultraviolet, first of its kind. The further increase in the brightness at those wavelengths helped in the more detailed study of the nova.[72][73]

In July 1994, an attempt was made to observe the impacts from fragments of the comet Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 with Jupiter.[72] The craft's position meant it had a direct line of sight to the impacts and observations were made in the ultraviolet and radio spectrum.[72] Voyager 2 failed to detect anything, with calculations showing that the fireballs were just below the craft's limit of detection.[72]

On November 29, 2006, a telemetered command to Voyager 2 was incorrectly decoded by its on-board computer—in a random error—as a command to turn on the electrical heaters of the spacecraft's magnetometer. These heaters remained turned on until December 4, 2006, and during that time, there was a resulting high temperature above 130 °C (266 °F), significantly higher than the magnetometers were designed to endure, and a sensor rotated away from the correct orientation.[74]

On August 30, 2007, Voyager 2 passed the termination shock and then entered into the heliosheath, approximately 1 billion mi (1.6 billion km) closer to the Sun than Voyager 1 did.[75] This is due to the interstellar magnetic field of deep space. The southern hemisphere of the Solar System's heliosphere is being pushed in.[76]

On April 22, 2010, Voyager 2 encountered scientific data format problems.[77] On May 17, 2010, JPL engineers revealed that a flipped bit in an on-board computer had caused the problem, and scheduled a bit reset for May 19.[78] On May 23, 2010, Voyager 2 resumed sending science data from deep space after engineers fixed the flipped bit.[79]

In 2013, it was originally thought that Voyager 2 would enter interstellar space in two to three years, with its plasma spectrometer providing the first direct measurements of the density and temperature of the interstellar plasma. But the Voyager project scientist, Edward C. Stone and his colleagues said they lacked evidence of what would be the key signature of interstellar space: a shift in the direction of the magnetic field.[10] Finally, in December 2018, Stone announced that Voyager 2 reached interstellar space on November 5, 2018.[8][9]

Maintenance to the Deep Space Network cut outbound contact with the probe for eight months in 2020. Contact was reestablished on November 2, when a series of instructions was transmitted, subsequently executed, and relayed back with a successful communication message.[80] On February 12, 2021, full communications were restored after a major ground station antenna upgrade that took a year to complete.[12]

In October 2020, astronomers reported a significant unexpected increase in density in the space beyond the Solar System as detected by the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2; this implies that "the density gradient is a large-scale feature of the VLISM (very local interstellar medium) in the general direction of the heliospheric nose".[81][82]

On July 18, 2023, Voyager 2 overtook Pioneer 10 as the second farthest spacecraft from the Sun.[32][33]

On July 21, 2023, a programming error misaligned Voyager 2's high gain antenna[83] 2 degrees away from Earth, breaking communications with the spacecraft. By August 1, the spacecraft's carrier signal was detected using multiple antennas of the Deep Space Network.[84][85] A high-power "shout" on August 4 sent from the Canberra station[86] successfully commanded the spacecraft to reorient towards Earth, resuming communications.[85][87] As a failsafe measure, the probe is also programmed to autonomously reset its orientation to point towards Earth, which would have occurred by October 15.[85]

Reductions in capabilities

[edit]As the power from the RTG slowly reduces, various items of equipment have been turned off on the spacecraft.[88] The first science equipment turned off on Voyager 2 was the PPS in 1991, which saved 1.2 watts.[88]

| Year | End of specific capabilities as a result of the available electrical power limitations[89] |

|---|---|

| 1998 | Termination of scan platform and UVS observations[88] |

| 2007 | Termination of Digital Tape Recorder (DTR) operations (It was no longer needed due to a failure on the High Waveform Receiver on the Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) on June 30, 2002.)[89] |

| 2008 | Power off Planetary Radio Astronomy Experiment (PRA)[88] |

| 2019 | CRS heater turned off[90] |

| 2021 | Turn off heater for Low Energy Charged Particle instrument[91] |

| 2023 | Software update reroutes power from the voltage regulator to keep the science instruments operating[21] |

| 2024 | Plasma Science instrument (PLS) turned off[92] |

| 2025 | Low-Energy Charged Particles (LECP) instrument terminated[93] |

| 2030 approx | Can no longer power any instrument[94] |

| 2036 | Out of range of the Deep Space Network[47] |

Concerns with the orientation thrusters

[edit]Some thrusters needed to control the correct attitude of the spacecraft and to point its high-gain antenna in the direction of Earth are out of use due to clogging problems in their hydrazine injector. The spacecraft no longer has backups available for its thruster system and "everything onboard is running on single-string" as acknowledged by Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at JPL, in an interview with Ars Technica.[95] NASA has decided to patch the computer software in order to modify the functioning of the remaining thrusters to slow down the clogging of the small diameter hydrazine injector jets. Before uploading the software update on the Voyager 1 computer, NASA will first try the procedure with Voyager 2, which is closer to Earth.[95]

Future of the probe

[edit]The probe is expected to keep transmitting weak radio messages until at least the mid-2020s, more than 48 years after it was launched.[89] NASA says that "The Voyagers are destined—perhaps eternally—to wander the Milky Way."[96]

Voyager 2 is not headed toward any particular star. The nearest star is 4.2 light-years away, and at 15.341 km/s, the spacecraft travels one light-year in about 19,541 years — during which time the nearby stars will also move substantially. In roughly 42,000 years, Voyager 2 will pass the star Ross 248 (10.30 light-years away from Earth) at a distance of 1.7 light-years.[97] If undisturbed for 296,000 years, Voyager 2 should pass by the star Sirius (8.6 light-years from Earth) at a distance of 4.3 light-years.[98]

Golden record

[edit]

Both Voyager space probes carry a gold-plated audio-visual disc, a compilation meant to showcase the diversity of life and culture on Earth in the event that either spacecraft is ever found by any extraterrestrial discoverer.[99][100] The record, made under the direction of a team including Carl Sagan and Timothy Ferris, includes photos of the Earth and its lifeforms, a range of scientific information, spoken greetings from people such as the Secretary-General of the United Nations, and a medley, "Sounds of Earth", that includes the sounds of whales, a baby crying, waves breaking on a shore, and a collection of music spanning different cultures and eras including works by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Blind Willie Johnson, Chuck Berry and Valya Balkanska. Other Eastern and Western classics are included, as well as performances of indigenous music from around the world. The record also contains greetings in 55 different languages.[101] The project aimed to portray the richness of life on Earth and stand as a testament to human creativity and the desire to connect with the cosmos.[100][102]

See also

[edit]- Family Portrait

- The Farthest, a 2017 documentary on the Voyager program.

- List of artificial objects leaving the Solar System

- List of missions to the outer planets

- New Horizons

- Pioneer 10

- Pioneer 11

- Timeline of artificial satellites and space probes

- Voyager 1

Notes

[edit]- ^ To observe Triton, Voyager 2 passed over Neptune's north pole, resulting in an acceleration out of the plane of the ecliptic, and, as a result, a reduced velocity relative to the Sun.[42]

- ^ Some sources cite the discovery of only 10 Uranian moons by Voyager 2,[52][53] but Perdita was discovered in Voyager 2 images more than a decade after they were taken.[54]

- ^ One of these moons, Larissa, was first reported in 1981 from ground telescope observations, but not confirmed until the Voyager 2 approach.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ "Voyager: Mission Information". NASA. 1989. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Voyager 2". US National Space Science Data Center. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Voyager 2". NASA's Solar System Exploration website. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Voyager – Mission Status". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ Staff (September 9, 2012). "Where are the Voyagers?". NASA. Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ University of Iowa (November 4, 2019). "Voyager 2 reaches interstellar space – Iowa-led instrument detects plasma density jump, confirming spacecraft has entered the realm of the stars". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (November 4, 2019). "Voyager 2's Discoveries From Interstellar Space – In its journey beyond the boundary of the solar wind's bubble, the probe observed some notable differences from its twin, Voyager 1". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Gill, Victoria (December 10, 2018). "Nasa's Voyager 2 probe 'leaves the Solar System'". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Dwayne; Fox, Karen; Cofield, Calia; Potter, Sean (December 10, 2018). "Release 18–115 – NASA's Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space". NASA. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "At last, Voyager 1 slips into interstellar space – Atom & Cosmos". Science News. September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ NASA Voyager – The Interstellar Mission Mission Overview Archived May 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Shannon Stirone (February 12, 2021). "Earth to Voyager 2: After a Year in the Darkness, We Can Talk to You Again – NASA's sole means of sending commands to the distant space probe, launched 44 years ago, is being restored on Friday". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Butrica, Andrew. From Engineering Science to Big Science. p. 267. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

Despite the name change, Voyager remained in many ways the Grand Tour concept, though certainly not the Grand Tour (TOPS) spacecraft.

- ^ Planetary Voyage Archived August 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory – California Institute of Technology. March 23, 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ David W. Swift (January 1, 1997). Voyager Tales: Personal Views of the Grand Tour. AIAA. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-56347-252-7.

- ^ Jim Bell (February 24, 2015). The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-698-18615-6.

- ^ a b "Voyager 2: Host Information". NASA. 1989. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ Ludwig, Roger; Taylor, Jim (2013). "Voyager Telecommunications" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "NASA News Press Kit 77–136". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ Furlong, Richard R.; Wahlquist, Earl J. (1999). "U.S. space missions using radioisotope power systems" (PDF). Nuclear News. 42 (4): 26–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "NASA's Voyager Will Do More Science With New Power Strategy". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "NASA Turns Off Science Instrument to Save Voyager 2 Power". NASA. October 1, 2024.

- ^ "MR-103". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ "Voyager Backgrounder" (PDF). Nasa.gov. Nasa. October 1980. Bibcode:1980voba.rept...... Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Koerner, Brendan (November 6, 2003). "What Fuel Does Voyager 1 Use?". Slate.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ NASA/JPL (August 26, 2003). "Voyager 1 Narrow Angle Camera Description". NASA / PDS. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ NASA/JPL (August 26, 2003). "Voyager 1 Wide Angle Camera Description". NASA / PDS. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Voyager 2 Full Mission Timeline" Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Muller, Daniel, 2010

- ^ "Voyager Mission Description" Archived October 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine NASA, February 19, 1997

- ^ "JPL Mission Information" Archived February 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine NASA, JPL, PDS.

- ^ Sullivant, Rosemary (November 5, 2011). "Voyager 2 to Switch to Backup Thruster Set". JPL. 2011-341. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "Distance between the Sun and Voyager 2". Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Distance between the Sun and Pioneer 10". Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ "NASA Turns Off Science Instrument to Save Voyager 2 Power – Voyager". blogs.nasa.gov. October 1, 2024.

- ^ "NASA Turns Off Two Voyager Science Instruments to Extend Mission". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Voyager - Fact Sheet". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Voyager - Fast Facts". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ HORIZONS Archived October 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, JPL Solar System Dynamics (Ephemeris Type ELEMENTS; Target Body: Voyager n (spacecraft); Center: Sun (body center); Time Span: launch + 1 month to Jupiter encounter – 1 month)

- ^ "40 Years Ago: Voyager 2 Explores Jupiter – NASA". July 8, 2019. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Littmann, Mark (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Corporation. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-43602-9.

- ^ Davies, John (January 23, 1986). "Voyage to the tilted planet". New Scientist. Vol. 109, no. 1492. pp. 39–42. Google Books sIkoAAAAMAAJ, vdc-AQAAIAAJ. HathiTrust mdp.39015038787464, uc1.31822015726458.

- ^ "Basics of space flight: Interplanetary Trajectories". Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "History". www.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Voyager Mission Description". pdsseti. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ "NASA – NSSDCA – Master Catalog – Event Query". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Saturn Approach". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Voyager – Frequently Asked Questions". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Laeser, Richard P. (1987). "Engineering the voyager uranus mission". Acta Astronautica. 16. Jet Propulsion Laboratory: 75–82. Bibcode:1986inns.iafcQ....L. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(87)90096-8. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory (May 30, 1995). "Lesson 394: Voyager Scan Platform Problems". NASA Public Lessons Learned System. NASA. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Bell, Jim (February 24, 2015). The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-698-18615-6. Archived from the original on September 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Uranus Approach" Archived September 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. Accessed December 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elizabeth Landau (2016) "Voyager Mission Celebrates 30 Years Since Uranus" Archived May 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine National Aeronautics and Space Administration, January 22, 2016. Accessed December 11, 2018

- ^ a b Voyager 2 Mission Team (2012) "1986: Voyager at Uranus" Archived May 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine NASA Science: Solar System Exploration, December 14, 2012. Accessed December 11, 2018.

- ^ Karkoschka, E. (2001). "Voyager's Eleventh Discovery of a Satellite of Uranus and Photometry and the First Size Measurements of Nine Satellites". Icarus. 151 (1): 69–77. Bibcode:2001Icar..151...69K. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6597.

- ^ Russell, C. T. (1993). "Planetary magnetospheres". Reports on Progress in Physics. 56 (6): 687–732. Bibcode:1993RPPh...56..687R. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/56/6/001. S2CID 250897924.

- ^ a b c d Aplin, K.L.; Fischer, G.; Nordheim, T.A.; Konovalenko, A.; Zakharenko, V.; Zarka, P. (2020). "Atmospheric Electricity at the Ice Giants". Space Science Reviews. 216 (2): 26. arXiv:1907.07151. Bibcode:2020SSRv..216...26A. doi:10.1007/s11214-020-00647-0.

- ^ a b c Zarka, P.; Pederson, B.M. (1986). "Radio detection of uranian lightning by Voyager 2". Nature. 323 (6089): 605-608. Bibcode:1986Natur.323..605Z. doi:10.1038/323605a0.

- ^ Hatfield, Miles (March 25, 2020). "Revisiting Decades-Old Voyager 2 Data, Scientists Find One More Secret – Eight and a half years into its grand tour of the solar system, NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft was ready for another encounter. It was Jan. 24, 1986, and soon it would meet the mysterious seventh planet, icy-cold Uranus". NASA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Andrews, Robin George (March 27, 2020). "Uranus Ejected a Giant Plasma Bubble During Voyager 2's Visit – The planet is shedding its atmosphere into the void, a signal that was recorded but overlooked in 1986 when the robotic spacecraft flew past". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "Voyager Steered Toward Neptune". Ukiah Daily Journal. March 15, 1987. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ a b National Aeronautics and Space Administration "Neptune Approach" Archived September 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory: California Institute of Technology. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Neptune". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Borucki, W.J. (1989). "Predictions of lightning activity at Neptune". Geophysical Research Letters. 16 (8): 937-939. Bibcode:1989GeoRL..16..937B. doi:10.1029/gl016i008p00937.

- ^ a b c d Gurnett, D. A.; Kurth, W. S.; Cairns, I. H.; Granroth, L. J. (1990). "Whistlers in Neptune's magnetosphere: Evidence of atmospheric lightning". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics. 95 (A12): 20967-20976. Bibcode:1990JGR....9520967G. doi:10.1029/ja095ia12p20967. hdl:2060/19910002329.

- ^ Belcher, J.W.; Bridge, H.S.; Bagenal, F.; Coppi, B.; Divers, O.; Eviatar, A.; Gordon, G.S.; Lazarus, A.J.; McNutt, R.L.; Ogilvie, K.W.; Richardson, J.D.; Siscoe, G.L.; Sittler, E.C.; Steinberg, J.T.; Sullivan, J.D.; Szabo, A.; Villanueva, L.; Vasyliunas, V.M.; Zhang, M. (1989). "Plasma observations near Neptune: Initial results from Voyager 2". Science. 246 (4936): 1478–1483. Bibcode:1989Sci...246.1478B. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1478. PMID 17756003.

- ^ National Aeronautics and Space Administration "Neptune Moons" Archived April 10, 2020, at the Wayback Machine NASA Science: Solar System Exploration. Updated December 6, 2017. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Howell (2016) "Neptune's Moons: 14 Discovered So Far" Archived December 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Space.com, June 30, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- ^ Phil Plait (2016) "Neptune Just Got a Little Dark" Archived December 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Slate, June 24, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- ^ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (1998) "Hubble Finds New Dark Spot on Neptune" Archived June 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory: California Institute of Technology, August 2, 1998. Accessed December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Voyager Space Flight Operations Schedule" (PDF). Voyager Mission Status. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. September 7, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ "Voyager Weekly Reports". Voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. September 6, 2013. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Ulivi, Paolo; Harland, David M (2007). Robotic Exploration of the Solar System Part I: The Golden Age 1957–1982. Springer. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-387-49326-8.

- ^ V1974 Cygni 1992: The Most Important Nova of the Century (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ Shuai, Ping (2021). Understanding Pulsars and Space Navigations. Springer Singapore. p. 189. ISBN 9789811610677. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "NASA – Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Voyager 2 finds solar system's shape is 'dented' # 2007-12-10, Week Ending December 14, 2007. Archived September 27, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ^ John Antczak (May 6, 2010). "NASA working on Voyager 2 data problem". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Engineers Diagnosing Voyager 2 Data System". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ "NASA Fixes Bug On Voyager 2". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Dockrill, Peter (November 5, 2020). "NASA finally makes contact with Voyager 2 after longest radio silence in 30 years". Live Science. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (October 19, 2020). "Voyager Spacecraft Detect an Increase in The Density of Space Outside The Solar System". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Kurth, W.S.; Gurnett, D.A. (August 25, 2020). "Observations of a Radial Density Gradient in the Very Local Interstellar Medium by Voyager 2". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 900 (1): L1. Bibcode:2020ApJ...900L...1K. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abae58. S2CID 225312823.

- ^ Inskeep, Steve (August 2, 2023). "NASA loses contact with Voyager Two after a programming error on Earth". NPR. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Voyager 2: Nasa picks up 'heartbeat' signal after sending wrong command". BBC News. August 1, 2023. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Mission Update: Voyager 2 Communications Pause – The Sun Spot". blogs.nasa.gov. July 28, 2023. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ Ellen Francis (August 5, 2023). "'Interstellar shout' restores NASA contact with lost Voyager 2 spacecraft". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ "Voyager 2: Nasa fully back in contact with lost space probe". BBC News. August 4, 2023. Archived from the original on August 4, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Voyager – Operations Plan to the End Mission". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Voyager – Spacecraft – Spacecraft Lifetime". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. March 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "A New Plan for Keeping NASA's Oldest Explorers Going". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Stirone, Shannon (February 12, 2021). "Earth to Voyager 2: After a Year in the Darkness, We Can Talk to You Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "NASA Turns Off Science Instrument to Save Voyager 2 Power". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. October 1, 2024.

- ^ "Where Are Voyager 1 and 2 Now? - NASA Science". March 10, 2024. Retrieved August 30, 2025.

- ^ Folger, T. (July 2022). "Record-Breaking Voyager Spacecraft Begin to Power Down". Scientific American. 327 (1): 26. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0722-26. PMID 39016957. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (October 24, 2023). "NASA wants the Voyagers to age gracefully, so it's time for a software patch". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ "Future". NASA. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ Bailer-Jones, Coryn A. L.; Farnocchia, Davide (April 3, 2019). "Future stellar flybys of the Voyager and Pioneer spacecraft". Research Notes of the AAS. 3 (4): 59. arXiv:1912.03503. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3...59B. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab158e. S2CID 134524048.

- ^ Baldwin, Paul (December 4, 2017). "NASA's Voyager 2 heads for star Sirius... by time it arrives humans will have died out". Express.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Ferris, Timothy (May 2012). "Timothy Ferris on Voyagers' Never-Ending Journey". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Gambino, Megan. "What Is on Voyager's Golden Record?". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Voyager Golden record". JPL. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Ferris, Timothy (August 20, 2017). "How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- "Saturn Science Results". Voyager Science Results at Saturn. Retrieved February 8, 2005.

- "Uranus Science Results". Voyager Science Results at Uranus. Retrieved February 8, 2005.

- Nardo, Don (2002). Neptune. Thomson Gale. ISBN 0-7377-1001-2

- JPL Voyager Telecom Manual

External links

[edit]- NASA Voyager website

- Voyager 2 Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Voyager 2 (NSSDC Master Catalog) Archived January 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

Voyager 2

View on GrokipediaDevelopment and Launch

Background and Objectives

The Voyager 2 mission originated as part of NASA's ambitious Voyager program, which evolved from the earlier Mariner series of planetary probes during the height of the 1970s space exploration efforts amid the ongoing Cold War-era competition in space achievements.[1][7] Conceived in the mid-1960s, the program initially drew on Mariner-class spacecraft designs for efficient, cost-effective interplanetary travel, with Voyager spacecraft originally designated as Mariner 11 and Mariner 12 until their renaming in March 1977.[1][8] This evolution reflected NASA's shift toward grand-scale outer solar system exploration following the successes of Mariner missions to Venus, Mars, and Mercury, aiming to extend robotic reconnaissance to the gas giants.[7] The primary scientific objectives of Voyager 2 centered on conducting detailed investigations of the outer planets' atmospheres, magnetospheres, ring systems, and moons to enhance understanding of their formation, evolution, and potential for habitability.[9][10] Specifically, the mission sought to characterize atmospheric circulation, composition, and dynamics; map magnetic fields and plasma environments; analyze ring structures and compositions; and survey moons for geological features that might indicate subsurface oceans or other conditions conducive to life, such as on Europa or Titan during earlier flybys shared with Voyager 1.[11][9] These goals built on preliminary data from Pioneer 10 and 11, prioritizing comparative planetology to reveal how the giant planets shaped the solar system's architecture.[10] Planning for Voyager 2 capitalized on a rare once-in-175-years alignment of the outer planets in the late 1970s, enabling a "grand tour" trajectory that used gravity assists to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune with minimal propulsion.[8] This alignment, occurring roughly every 175 years, opened a narrow launch window from 1976 to 1980, allowing efficient multi-planet exploration that would otherwise require decades or advanced propulsion unavailable at the time.[8] To mitigate risks, NASA decided to launch Voyager 2 first on August 20, 1977, positioning it for the full grand tour, while Voyager 1 followed on September 5, 1977, on a shorter path; this order permitted Voyager 1 to be retargeted for the grand tour if Voyager 2 failed during launch or early operations.[10][8] The Voyager program's development timeline spanned from initial concept studies in 1965 to approval in 1972, with spacecraft construction and testing completed by 1977 under a total budget of approximately $360 million for both Voyagers, later adjusted to around $320 million due to scaled-back ambitions from the original grand tour proposal.[8] Key personnel included Edward C. Stone, who served as project scientist from 1972 to 2022, overseeing scientific planning and operations from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[9][8] Additionally, NASA approved the inclusion of a gold-plated phonograph record, known as the Golden Record, on both spacecraft as a symbolic message to potential extraterrestrial intelligence, curated by a committee led by Carl Sagan and containing sounds, images, and greetings from Earth to convey humanity's diversity and location.[12][8]Spacecraft Construction

The Voyager 2 spacecraft was assembled at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, from 1975 to 1977, following the approval of the Voyager program in 1972. JPL engineers designed and integrated the core structure, subsystems, and scientific components into a cohesive unit capable of withstanding the harsh conditions of deep space travel. The assembly process included rigorous testing for radiation exposure, thermal extremes ranging from -200°C to +200°C, and vacuum conditions to ensure reliability over decades. These tests simulated the environments encountered during planetary flybys and beyond, validating the spacecraft's durability before shipment to Kennedy Space Center for launch preparation.[13] The central element of the spacecraft was a ten-sided polygonal bus constructed from aluminum honeycomb panels, providing a lightweight yet robust framework weighing approximately 721.9 kilograms at launch, including fuel and scientific instruments. This structure measured about 1.78 meters across the flats and 0.46 meters in height, with overall dimensions expanding to roughly 3.7 meters by 3.2 meters by 2.1 meters when including deployed booms for the magnetometer and plasma instruments. Key integrations included the 3.7-meter diameter high-gain antenna, mounted directly on the bus for high-speed data transmission back to Earth, and the scan platform—a motorized, two-axis gimbal system extending up to 3 meters that allowed precise pointing of cameras and other sensors toward planetary targets without altering the spacecraft's orientation. The aluminum honeycomb material, combined with multilayer insulation blankets, protected internal electronics from micrometeoroids, cosmic radiation, and temperature fluctuations.[14][1][15] Voyager 2's onboard computing relied on three dual-redundant systems: the Command Computer Subsystem for sequencing commands, the Flight Data Subsystem for instrument data handling, and the Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem for orientation and platform control, totaling 68 kilobytes of plated-wire memory across all units. These 18-bit and 16-bit processors executed custom assembly language software, enabling autonomous fault detection, sequence execution, and attitude adjustments with minimal ground intervention to conserve power and bandwidth. The power for these systems came from three radioisotope thermoelectric generators using plutonium-238. The entire Voyager program, encompassing both spacecraft, cost $865 million from 1972 through the Neptune encounter in 1989.[6][16]Launch and Initial Trajectory

Voyager 2 was launched on August 20, 1977, at 14:29:44 UT from Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, aboard a Titan IIIE-Centaur rocket designated TC-7.[1] This launch preceded that of Voyager 1 by 16 days to provide additional time for potential trajectory adjustments, as Voyager 2 followed a more complex path enabling visits to all four outer planets if the mission parameters allowed.[17] The rocket's Centaur upper stage imparted an initial heliocentric velocity of approximately 17.1 km/s to the spacecraft, sufficient to escape Earth's gravity and place it on a trajectory toward the outer solar system.[17] Post-launch, the spacecraft separated from the Centaur stage about 260 seconds after ignition, achieving Earth escape energy and beginning its outbound journey.[18] Early flight operations included initial communication checks via NASA's Deep Space Network, which successfully acquired the spacecraft's signal shortly after launch and confirmed nominal performance of its systems.[19] The first trajectory correction maneuver (TCM-1) occurred on October 11, 1977, refining the path to Jupiter with high precision, achieving the desired delta-v to within one percent.[19] Subsequent maneuvers, such as TCM-2 on May 3, 1978, further aligned the trajectory, ensuring the spacecraft's hyperbolic approach to the gas giants. No major anomalies were reported during this initial phase, though routine checks verified the activation of scientific instruments, which began collecting preliminary data on cosmic rays, plasma waves, and solar wind particles as Voyager 2 traversed the inner solar system.[20] The mission's trajectory relied on the gravity assist technique, where the spacecraft uses a planet's gravitational field to alter its velocity and direction without expending fuel, effectively "slingshotting" it toward subsequent targets.[21] This method enabled Voyager 2's grand tour by converting some of the planet's orbital momentum into additional speed for the probe. The path consisted of a series of hyperbolic orbits around each planet, with the Jupiter encounter planned for a closest approach of approximately 645,000 km on July 9, 1979, providing the initial boost for the Saturn flyby while allowing detailed observations.[1] Later assists at Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune extended the trajectory into interstellar space, demonstrating the efficiency of this propulsion strategy for deep space exploration.[22]Design and Systems

Structure and Propulsion

Voyager 2's structural framework centers on a ten-sided polygonal bus, approximately 1.8 meters across and constructed from aluminum honeycomb panels, which serves as the core platform for mounting electronics, instruments, and subsystems. This bus is integrated with a tubular truss assembly that supports the 3.7-meter high-gain antenna, ensuring stable communication orientation throughout the mission. Extending from the bus are several deployable booms, including a 13-meter magnetometer boom made of epoxy glass for low-magnetic-field measurements and a 2.3-meter graphite-epoxy science boom that positions the scan platform away from spacecraft interference. The scan platform itself, a two-axis articulated mechanism weighing 103 kilograms, enables precise pointing of remote-sensing instruments such as cameras and spectrometers, achieving an accuracy of 2.5 milliradians (approximately 0.14 degrees) to capture detailed planetary imagery.[23][24][25] The propulsion system relies on a monopropellant hydrazine setup for both trajectory adjustments and attitude maintenance, comprising 16 low-thrust engines each delivering 0.889 newtons of force. These thrusters are distributed across the spacecraft: three primary units dedicated to major trajectory correction maneuvers (TCMs), eight for fine attitude control, and five as backups to enhance reliability over the long mission duration. At launch, the system carried 104 kilograms of hydrazine fuel, stored in four spherical tanks pressurized by helium, enabling a blowdown mode operation without complex regulators. This configuration provided the necessary impulse for interplanetary course corrections without the need for larger engines post-launch.[23] Attitude and articulation control is managed by the three-axis stabilized system, which uses a combination of inertial and celestial references to maintain the high-gain antenna's Earth-pointing accuracy within 0.05 degrees. Key components include three redundant two-axis gyroscopes for short-term stability, Canopus star trackers for precise angular measurements against the star Canopus, and coarse sun sensors that detect solar position through slots in the antenna dish to provide coarse attitude updates. Following early mission anomalies, such as sensor degradations, the system incorporated built-in redundancies, including backup trackers and gyros, allowing seamless switching to preserve orientation control as the spacecraft ventured farther from the Sun.[23][15] The overall delta-V budget for propulsion maneuvers totals approximately 190 meters per second, sufficient to support multiple TCMs across the mission's planetary flybys and interstellar extension. For instance, post-launch corrections near Jupiter involved burns on the scale of several meters per second to refine the trajectory for subsequent encounters, demonstrating the system's efficiency in conserving fuel for long-term operations.[23] Thermal management addresses extreme environmental variations, from near-Earth solar intensities to deep-space cold, using a passive-active hybrid approach. Radioisotope heater units (RHUs), each generating 1 watt from plutonium-238 decay without producing electricity, are strategically placed on sensitive components like the magnetometer boom, sun sensors, and scan platform to prevent freezing. Complementing these are four sets of louvers on the electronics bays and mini-louvers on the scan platform and cosmic ray instrument, which automatically adjust to radiate excess heat or retain warmth, maintaining internal temperatures within operational limits despite swings from -79°C to 100°C and external conditions dropping to around -160°C near Saturn.[23]Power and Communications

Voyager 2's electrical power is supplied by three Multi-Hundred Watt radioisotope thermoelectric generators (MHW-RTGs) fueled by plutonium-238, which convert the heat from radioactive decay into electricity through thermoelectric conversion.[26] At launch in 1977, the RTGs generated approximately 470 watts of electrical power at 30 volts DC on an unregulated bus.[27] This power is distributed to subsystems via DC-DC converters that step down to regulated 5-volt and other low-voltage supplies for electronics and instruments. The initial usable power budget was about 420 watts, supporting all operations during the early planetary encounters. Due to the half-life of plutonium-238 (approximately 87.7 years), the RTGs' output decays by roughly 4 watts per year, reducing the total available power to around 225 watts by April 2024 and an estimated 220 watts by late 2025.[28] The communications system enables Voyager 2 to transmit scientific data and receive commands across vast distances using a 23-watt X-band traveling-wave tube amplifier operating at 8.4 GHz for downlink telemetry.[29] Data is directed through a 3.7-meter high-gain parabolic antenna, which provides focused transmission and reception capabilities.[15] At the distance of the Neptune flyby in 1989 (about 30 AU from Earth), the typical data rate was 160 bits per second under normal engineering constraints, though higher rates up to 115 kilobits per second were possible during close encounters with burst transmissions.[11] As of 2025, with the spacecraft at approximately 141 AU (over 21 billion kilometers) from Earth, one-way signal travel time exceeds 19.5 hours, necessitating careful command sequencing.[4] Ground communication relies on NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN), comprising three primary complexes in Goldstone, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia, which provide continuous tracking, command uplink via S-band at 2.3 GHz, and data downlink reception with large dish antennas up to 70 meters in diameter.[29] To ensure reliable transmission over noisy deep-space channels, data employs convolutional coding with a rate of 1/2 and constraint length 7, often concatenated with Reed-Solomon outer codes for error correction, achieving low bit error rates even at faint signal strengths.[30] Over the mission's duration, NASA developed adaptive compression techniques, such as predictive coding for images and telemetry, to maximize data return within the constrained bit rates as power and distance limited bandwidth.Scientific Instruments

Voyager 2 carried a suite of 11 scientific instruments designed to investigate the outer planets, their satellites, magnetospheres, and the interplanetary medium, as part of 11 investigations including radio science. These instruments were mounted on the spacecraft's science deck and scan platform, enabling comprehensive remote sensing and in-situ measurements. The payload emphasized multispectral imaging, particle detection, and field measurements to capture data across electromagnetic spectra and particle energies.[11] The instruments include the Imaging Science System (ISS), consisting of two vidicon cameras—a narrow-angle camera with 1500 mm focal length and f/8.5 aperture, and a wide-angle camera with 200 mm focal length and f/3 aperture—each equipped with an 800 × 800 pixel vidicon tube and multiple filters for visible and near-infrared imaging to resolve planetary surfaces and atmospheres at scales down to kilometers per pixel during close encounters. The Infrared Interferometer Spectrometer (IRIS) measured thermal emissions and atmospheric compositions in the 2.5–50 μm range, providing spectra to analyze temperature profiles and trace gases. The Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) observed emissions from 40–180 nm to study upper atmospheres, aurorae, and ionospheres through high-resolution grating spectroscopy.[11][31] The Triaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer (MAG) detected magnetic fields with dual sensors, covering ranges from 0.006 nT to 20 gauss to map planetary magnetospheres and interplanetary fields with high temporal resolution. The Plasma Spectrometer (PLS) analyzed low-energy ions and electrons (up to 10 keV) using Faraday cup detectors to measure solar wind parameters like density, velocity, and temperature. The Low-Energy Charged Particle (LECP) instrument employed scanning telescopes to detect ions and electrons from 10 eV to 40 MeV, characterizing energetic particle populations in planetary environments and the heliosphere. The Cosmic Ray Subsystem (CRS) measured high-energy particles (electrons 3–110 MeV, nuclei 1–500 MeV/nuc) with solid-state detectors and scintillation counters to study galactic cosmic rays and solar energetic particles.[11][32] Additional instruments included the Planetary Radio Astronomy (PRA) system, which used dual antennas to detect radio emissions from 20.4 kHz to 40.5 MHz, investigating planetary magnetospheric radio sources and solar wind interactions. The Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) recorded electric field waves from 10 Hz to 56 kHz via long antennas, analyzing plasma densities, wave modes, and dust impacts. The Photopolarimeter System (PPS) featured a 0.2 m telescope to measure light polarization and intensity from 235–750 nm, probing atmospheric scattering and ring structures. Radio science investigations utilized the spacecraft's telecommunications system as a probe for gravity fields, atmospheres, and ionospheres during flybys. An Optical Calibration Target (OCT) provided a known reference for in-flight calibration of scan platform instruments.[11] Pre-mission calibration and testing occurred at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), including vibration, thermal vacuum, and electromagnetic compatibility tests to ensure performance under space conditions. Instruments underwent radiation hardening evaluations, such as proton and electron exposure simulations using facilities like the JPL Dynamitron, to withstand Jupiter's intense radiation belts (up to 10^8 rads total dose). The total science payload mass was approximately 105 kg, with power consumption around 100 W for electronics plus 10 W for heaters at nominal operation. Most instruments featured a dual-string redundancy design, with parallel electronics chains switchable via ground command to enhance reliability against single-point failures.[13][33]Planetary Encounters

Jupiter Flyby

Voyager 2 began its Jupiter encounter on April 24, 1979, approaching the planet for a series of targeted observations that culminated in its closest approach on July 9, 1979, when it passed within 570,000 kilometers (350,000 miles) of the cloud tops.[34] The spacecraft conducted an intense observation period over approximately 48 hours around closest approach, capturing high-resolution images and data on the planet's atmosphere, magnetosphere, and satellites using its suite of instruments.[10] This flyby provided the second detailed survey of the Jovian system following Voyager 1's earlier passage, building on initial findings with complementary trajectories that allowed for outbound observations of features missed inbound.[34] Key observations included detailed imaging of the Great Red Spot, revealing it as a vast, anticyclonic storm system with turbulent internal dynamics and surrounding smaller vortices interacting with the planet's banded cloud layers.[34] Voyager 2 also confirmed and expanded on the discovery of active volcanism on Io, observing multiple plumes during a dedicated 10-hour monitoring sequence from a distance of about 1.1 million kilometers (702,200 miles), marking the first extraterrestrial volcanic activity verified beyond Earth.[34] These plumes were later identified as ejecting sulfur-rich material, contributing to Io's colorful surface and tenuous atmosphere. The spacecraft's instruments further mapped Jupiter's magnetosphere, detecting its vast extent with a tail stretching over 600 million kilometers toward the outer solar system, influenced by interactions with the solar wind and Io's plasma torus.[35] During the encounter, Voyager 2 performed close flybys of several moons, obtaining detailed images of Amalthea at 559,000 kilometers (347,000 miles), revealing its irregular, potato-shaped form; Europa at 206,000 kilometers (127,900 miles), showing a cracked, icy surface suggestive of subsurface processes; Ganymede at 62,100 kilometers (38,600 miles), highlighting cratered terrains and possible tectonic features; and Callisto at 215,000 kilometers (133,600 miles), displaying heavily cratered, ancient crust.[34] Io was observed from afar but with focus on its dynamic surface changes due to ongoing eruptions.[34] Atmospheric measurements indicated zonal winds reaching speeds of up to 540 kilometers per hour (335 miles per hour) in the equatorial regions, driven by the planet's rapid rotation, with a composition dominated by approximately 90% hydrogen and 10% helium by volume.[36][37] An early anomaly during the approach involved the failure of Voyager 2's primary radio receiver in April 1978, necessitating a switch to the backup system, which performed reliably throughout the flyby without impacting data return.[34] No major imaging issues were reported specific to the Jupiter encounter, allowing for the successful transmission of over 16,000 images from Voyager 2 alone.[10]Saturn Flyby

Voyager 2's encounter with Saturn began with long-range observations starting on June 5, 1981, from a distance of 41 million miles, following trajectory adjustments made after its Jupiter flyby in 1979 to optimize the path for the Saturn targeting and subsequent outer planet encounters.[38] The spacecraft achieved its closest approach to Saturn on August 25, 1981, passing 161,000 km from the planet's center of mass, or approximately 41,000 km above the cloud tops. Observations continued until September 28, 1981, providing a comprehensive dataset during the four-month period.[38] The flyby revolutionized understanding of Saturn's ring system, revealing thousands of narrow ringlets within the main rings and transient spoke-like features in the B ring, imaged from about 2.5 million miles away on August 22, 1981.[38] Voyager 2 also identified the roles of small shepherd moons, such as Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit approximately 1,800 km apart and gravitationally confine the narrow F ring through their influence on ring particles.[38] These discoveries highlighted the dynamic, moon-driven structure of the rings, with embedded bodies creating gaps and density waves.[39] A dedicated flyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, occurred on August 24, 1981, at a distance of 413,000 miles, where Voyager 2 probed its thick atmosphere composed primarily of nitrogen with traces of methane and hydrocarbons.[38] The dense haze layers obscured the surface, presenting Titan as a featureless orange globe, but infrared and ultraviolet data suggested the presence of methane-driven processes, including potential liquid hydrocarbon reservoirs.[39] In Saturn's atmosphere, Voyager 2 captured evidence of a persistent hexagonal jet stream encircling the north pole, a unique wave pattern in the polar vortex, alongside zonal bands and high-altitude clouds.[39] Measurements indicated intense zonal winds, with equatorial speeds reaching up to 1,800 km/h eastward, five times stronger than those on Jupiter and driven by internal heat sources.[40] Voyager 2 provided high-resolution images of several inner moons during the encounter, including close passes by Enceladus at 54,000 miles and Tethys at 58,000 miles on August 25, 1981, revealing cratered terrains and tectonic features.[38] It also imaged Mimas, showcasing its distinctive large impact crater, and contributed confirmatory observations of the small moon Atlas, first discovered by Voyager 1, highlighting its position near the A ring.[39]Uranus Flyby