Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Minor planet

View on WikipediaAccording to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet.[a] Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term minor planet, but that year's meeting reclassified minor planets and comets into dwarf planets and small Solar System bodies (SSSBs).[1] In contrast to the eight official planets of the Solar System, all minor planets fail to clear their orbital neighborhood.[2][1]

Minor planets include asteroids (near-Earth objects, Earth trojans, Mars trojans, Mars-crossers, main-belt asteroids and Jupiter trojans), as well as distant minor planets (Uranus trojans, Neptune trojans, centaurs and trans-Neptunian objects), most of which reside in the Kuiper belt and the scattered disc. As of October 2025[update], there are 1,472,966 known objects, divided into 875,150 numbered, with only one of them recognized as a dwarf planet (secured discoveries) and 597,816 unnumbered minor planets, with only five of those officially recognized as a dwarf planet.[3]

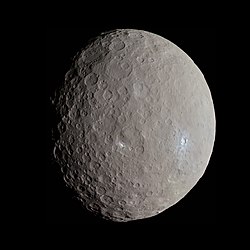

The first minor planet to be discovered was Ceres in 1801, though it was called a 'planet' at the time and an 'asteroid' soon after; the term minor planet was not introduced until 1841, and was considered a subcategory of 'planet' until 1932.[4] The term planetoid has also been used, especially for larger, planetary objects such as those the IAU has called dwarf planets since 2006.[5][6] Historically, the terms asteroid, minor planet, and planetoid have been more or less synonymous.[5][7] This terminology has become more complicated by the discovery of numerous minor planets beyond the orbit of Jupiter, especially trans-Neptunian objects that are generally not considered asteroids.[7] A minor planet seen releasing gas may be dually classified as a comet.

Objects are called dwarf planets if their own gravity is sufficient to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium and form an ellipsoidal shape. All other minor planets and comets are called small Solar System bodies.[1] The IAU stated that the term minor planet may still be used, but the term small Solar System body will be preferred.[8] However, for purposes of numbering and naming, the traditional distinction between minor planet and comet is still used.

Populations

[edit]

Hundreds of thousands of minor planets have been discovered within the Solar System and thousands more are discovered each month. The Minor Planet Center has documented over 213 million observations and 794,832 minor planets, of which 541,128 have orbits known well enough to be assigned permanent official numbers.[9][10] Of these, 21,922 have official names.[9] As of 3 November 2025[update], the lowest-numbered unnamed minor planet is (4596) 1981 QB,[11] and the highest-numbered named minor planet is 841529 Jonahwoodhams.[12]

There are various broad minor-planet populations:

- Asteroids; traditionally, most have been bodies in the inner Solar System.[7]

- Near-Earth asteroids, those whose orbits take them inside the orbit of Mars. Further subclassification of these, based on orbital distance, is used:[13]

- Apohele asteroids orbit inside of Earth's perihelion distance and thus are contained entirely within the orbit of Earth.

- Aten asteroids, those that have a semimajor axis of less than Earth's and an aphelion (furthest distance from the Sun) greater than 0.983 AU.

- Apollo asteroids are those asteroids with a semimajor axis greater than Earth's while having a perihelion distance of 1.017 AU or less. Like Aten asteroids, Apollo asteroids are Earth-crossers.

- Amor asteroids are those near-Earth asteroids that approach the orbit of Earth from beyond but do not cross it. Amor asteroids are further subdivided into four subgroups, depending on where their semimajor axis falls between Earth's orbit and the asteroid belt.

- Earth trojans, asteroids sharing Earth's orbit and gravitationally locked to it. As of 2022, two Earth trojans are known: 2010 TK7 and 2020 XL5.[14]

- Mars trojans, asteroids sharing Mars's orbit and gravitationally locked to it. As of 2007, eight such asteroids are known.[15][16]

- Asteroid belt, whose members follow roughly circular orbits between Mars and Jupiter. These are the original and best-known group of asteroids.

- Jupiter trojans, asteroids sharing Jupiter's orbit and gravitationally locked to it. Numerically they are estimated to equal the main-belt asteroids.

- Near-Earth asteroids, those whose orbits take them inside the orbit of Mars. Further subclassification of these, based on orbital distance, is used:[13]

- Distant minor planets, an umbrella term for minor planets in the outer Solar System.

- Centaurs, bodies in the outer Solar System between Jupiter and Neptune. They have unstable orbits due to the gravitational influence of the giant planets, and therefore must have come from elsewhere, probably outside Neptune.[17]

- Neptune trojans, bodies sharing Neptune's orbit and gravitationally locked to it. Although only a handful are known, there is evidence that Neptune trojans are more numerous than either the asteroids in the asteroid belt or the Jupiter trojans.[18]

- Trans-Neptunian objects, bodies at or beyond the orbit of Neptune, the outermost planet.

- The Kuiper belt, objects inside an apparent population drop-off approximately 55 AU from the Sun.

- Classical Kuiper belt objects like Makemake, also known as cubewanos, are in primordial, relatively circular orbits that are not in resonance with Neptune.

- Resonant Kuiper belt objects.

- Scattered disc objects like Eris, with aphelia outside the Kuiper belt. These are thought to have been scattered by Neptune.

- Detached objects such as Sedna, with both an aphelion and a perihelion outside the Kuiper belt.

- Sednoids, detached objects with a perihelion greater than 75 AU (Sedna, 2012 VP113, and Leleākūhonua).

- The Oort cloud, a hypothetical population thought to be the source of long-period comets and that may extend to 50,000 AU from the Sun.

- The Kuiper belt, objects inside an apparent population drop-off approximately 55 AU from the Sun.

Naming conventions

[edit]

All astronomical bodies in the Solar System need a distinct designation. The naming of minor planets runs through a three-step process. First, a provisional designation is given upon discovery—because the object still may turn out to be a false positive or become lost later on—called a provisionally designated minor planet. After the observation arc is accurate enough to predict its future location, a minor planet is formally designated and receives a number. It is then a numbered minor planet. Finally, in the third step, it may be named by its discoverers. However, only a small fraction of all minor planets have been named. The vast majority are either numbered or have still only a provisional designation. Example of the naming process:

- 1932 HA – provisional designation upon discovery on 24 April 1932

- (1862) 1932 HA – formal designation, receives an official number

- 1862 Apollo – named minor planet, receives a name, the alphanumeric code is dropped

Provisional designation

[edit]A newly discovered minor planet is given a provisional designation. For example, the provisional designation 2002 AT4 consists of the year of discovery (2002) and an alphanumeric code indicating the half-month of discovery and the sequence within that half-month. Once an asteroid's orbit has been confirmed, it is given a number, and later may also be given a name (e.g. 433 Eros). The formal naming convention uses parentheses around the number, but dropping the parentheses is quite common. Informally, it is common to drop the number altogether or to drop it after the first mention when a name is repeated in running text.

Minor planets that have been given a number but not a name keep their provisional designation, e.g. (29075) 1950 DA. Because modern discovery techniques are finding vast numbers of new asteroids, they are increasingly being left unnamed. The earliest discovered to be left unnamed was for a long time (3360) 1981 VA, now 3360 Syrinx. In November 2006 its position as the lowest-numbered unnamed asteroid passed to (3708) 1974 FV1 (now 3708 Socus), and in May 2021 to (4596) 1981 QB. On rare occasions, a small object's provisional designation may become used as a name in itself: the then-unnamed (15760) 1992 QB1 gave its "name" to a group of objects that became known as classical Kuiper belt objects ("cubewanos") before it was finally named Albion in January 2018.[20]

A few objects are cross-listed as both comets and asteroids, such as 4015 Wilson–Harrington, which is also listed as 107P/Wilson–Harrington.

Numbering

[edit]Minor planets are awarded an official number once their orbits are confirmed. With the increasing rapidity of discovery, these are now six-figure numbers. The switch from five figures to six figures arrived with the publication of the Minor Planet Circular (MPC) of October 19, 2005, which saw the highest-numbered minor planet jump from 99947 to 118161.[9]

Naming

[edit]The first few asteroids were named after figures from Greek and Roman mythology, but as such names started to dwindle the names of famous people, literary characters, discoverers' spouses, children, colleagues, and even television characters were used.

Gender

[edit]- The first asteroid to be given a non-mythological name was 20 Massalia, named after the Greek name for the city of Marseille.[21] The first to be given an entirely non-Classical name was 45 Eugenia, named after Empress Eugénie de Montijo, the wife of Napoleon III. For some time only female (or feminized) names were used; Alexander von Humboldt was the first man to have an asteroid named after him, but his name was feminized to 54 Alexandra. This unspoken tradition lasted until 334 Chicago was named; even then, female names showed up in the list for years after.

Eccentric

[edit]- As the number of asteroids began to run into the hundreds, and eventually, in the thousands, discoverers began to give them increasingly frivolous names. The first hints of this were 482 Petrina and 483 Seppina, named after the discoverer's pet dogs. However, there was little controversy about this until 1971, upon the naming of 2309 Mr. Spock (the name of the discoverer's cat). Although the IAU subsequently discouraged the use of pet names as sources,[22] eccentric asteroid names are still being proposed and accepted, such as 4321 Zero, 6042 Cheshirecat, 9007 James Bond, 13579 Allodd and 24680 Alleven, and 26858 Misterrogers.

Discoverer's name

[edit]- A well-established rule is that, unlike comets, minor planets may not be named after their discoverer(s). One way to circumvent this rule has been for astronomers to exchange the courtesy of naming their discoveries after each other. Rare exceptions to this rule are 1927 Suvanto and 96747 Crespodasilva. 1927 Suvanto was named after its discoverer, Rafael Suvanto, posthumously by the Minor Planet Center. He died four years after the discovery in the last days of the Finnish winter war of 1939-40.[23] 96747 Crespodasilva was named after its discoverer, Lucy d'Escoffier Crespo da Silva, because she died shortly after the discovery, at age 22.[24][25]

Languages

[edit]- Names were adapted to various languages from the beginning. 1 Ceres, Ceres being its Anglo-Latin name, was actually named Cerere, the Italian form of the name. German, French, Arabic, and Hindi use forms similar to the English, whereas Russian uses a form, Tserera, similar to the Italian. In Greek, the name was translated to Δήμητρα (Demeter), the Greek equivalent of the Roman goddess Ceres. In the early years, before it started causing conflicts, asteroids named after Roman figures were generally translated in Greek; other examples are Ἥρα (Hera) for 3 Juno, Ἑστία (Hestia) for 4 Vesta, Χλωρίς (Chloris) for 8 Flora, and Πίστη (Pistis) for 37 Fides. In Chinese, the names are not given the Chinese forms of the deities they are named after, but rather typically have a syllable or two for the character of the deity or person, followed by 神 'god(dess)' or 女 'woman' if just one syllable, plus 星 'star/planet', so that most asteroid names are written with three Chinese characters. Thus Ceres is 穀神星 'grain goddess planet',[26] Pallas is 智神星 'wisdom goddess planet', etc.[citation needed]

Physical properties of comets and minor planets

[edit]Commission 15[27] of the International Astronomical Union is dedicated to the Physical Study of Comets & Minor Planets.

Archival data on the physical properties of comets and minor planets are found in the PDS Asteroid/Dust Archive.[28] This includes standard asteroid physical characteristics such as the properties of binary systems, occultation timings and diameters, masses, densities, rotation periods, surface temperatures, albedoes, spin vectors, taxonomy, and absolute magnitudes and slopes. In addition, European Asteroid Research Node (E.A.R.N.), an association of asteroid research groups, maintains a Data Base of Physical and Dynamical Properties of Near Earth Asteroids.[29]

Environmental properties

[edit]Environmental characteristics have three aspects: space environment, surface environment and internal environment, including geological, optical, thermal and radiological environmental properties, etc., which are the basis for understanding the basic properties of minor planets, carrying out scientific research, and are also an important reference basis for designing the payload of exploration missions

Radiation environment

[edit]Without the protection of an atmosphere and its own strong magnetic field, the minor planet's surface is directly exposed to the surrounding radiation environment. In the cosmic space where minor planets are located, the radiation on the surface of the planets can be divided into two categories according to their sources: one comes from the sun, including electromagnetic radiation from the sun, and ionizing radiation from the solar wind and solar energy particles; the other comes from outside the solar system, that is, galactic cosmic rays, etc.[30]

Optical environment

[edit]Usually during one rotation period of a minor planet, the albedo of a minor planet will change slightly due to its irregular shape and uneven distribution of material composition. This small change will be reflected in the periodic change of the planet's light curve, which can be observed by ground-based equipment, so as to obtain the planet's magnitude, rotation period, rotation axis orientation, shape, albedo distribution, and scattering properties. Generally speaking, the albedo of minor planets is usually low, and the overall statistical distribution is bimodal, corresponding to C-type (average 0.035) and S-type (average 0.15) minor planets.[31] In the minor planet exploration mission, measuring the albedo and color changes of the planet surface is also the most basic method to directly know the difference in the material composition of the planet surface.[32]

Geological environment

[edit]The geological environment on the surface of minor planets is similar to that of other unprotected celestial bodies, with the most widespread geomorphological feature present being impact craters: however, the fact that most minor planets are rubble pile structures, which are loose and porous, gives the impact action on the surface of minor planets its unique characteristics. On highly porous minor planets, small impact events produce spatter blankets similar to common impact events: whereas large impact events are dominated by compaction and spatter blankets are difficult to form, and the longer the planets receive such large impacts, the greater the overall density.[33] In addition, statistical analysis of impact craters is an important means of obtaining information on the age of a planet surface. Although the Crater Size-Frequency Distribution (CSFD) method of dating commonly used on minor planet surfaces does not allow absolute ages to be obtained, it can be used to determine the relative ages of different geological bodies for comparison.[34] In addition to impact, there are a variety of other rich geological effects on the surface of minor planets,[35] such as mass wasting on slopes and impact crater walls,[36] large-scale linear features associated with graben,[37] and electrostatic transport of dust.[38] By analysing the various geological processes on the surface of minor planets, it is possible to learn about the possible internal activity at this stage and some of the key evolutionary information about the long-term interaction with the external environment, which may lead to some indication of the nature of the parent body's origin. Many of the larger planets are often covered by a layer of soil (regolith) of unknown thickness. Compared to other atmosphere-free bodies in the solar system (e.g. the Moon), minor planets have weaker gravity fields and are less capable of retaining fine-grained material, resulting in a somewhat larger surface soil layer size.[39] Soil layers are inevitably subject to intense space weathering that alters their physical and chemical properties due to direct exposure to the surrounding space environment. In silicate-rich soils, the outer layers of Fe are reduced to nano-phase Fe (np-Fe), which is the main product of space weathering.[40] For some small planets, their surfaces are more exposed as boulders of varying sizes, up to 100 metres in diameter, due to their weaker gravitational pull.[41] These boulders are of high scientific interest, as they may be either deeply buried material excavated by impact action or fragments of the planet's parent body that have survived. The rocks provide more direct and primitive information about the material inside the minor planet and the nature of its parent body than the soil layer, and the different colours and forms of the rocks indicate different sources of material on the surface of the minor planet or different evolutionary processes.

Magnetic environment

[edit]Usually in the interior of the planet, the convection of the conductive fluid will generate a large and strong magnetic field. However, the size of a minor planet is generally small and most of the minor planets have a "crushed stone pile" structure, and there is basically no "dynamo" structure inside, so it will not generate a self-generated dipole magnetic field like the Earth. But some minor planets do have magnetic fields—on the one hand, some minor planets have remanent magnetism: if the parent body had a magnetic field or if the nearby planetary body has a strong magnetic field, the rocks on the parent body will be magnetised during the cooling process and the planet formed by the fission of the parent body will still retain remanence,[42] which can also be detected in extraterrestrial meteorites from the minor planets;[43] on the other hand, if the minor planets are composed of electrically conductive material and their internal conductivity is similar to that of carbon- or iron-bearing meteorites, the interaction between the minor planets and the solar wind is likely to be unipolar induction, resulting in an external magnetic field for the minor planet.[44] In addition, the magnetic fields of minor planets are not static; impact events, weathering in space and changes in the thermal environment can alter the existing magnetic fields of minor planets. At present, there are not many direct observations of minor planet magnetic fields, and the few existing planets detection projects generally carry magnetometers, with some targets such as Gaspra[45] and Braille[46] measured to have strong magnetic fields nearby, while others such as Lutetia have no magnetic field.[47]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Press release, IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes Archived 2020-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, International Astronomical Union, August 24, 2006. Accessed May 5, 2008.

- ^ "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Resolutions 5 and 6" (PDF). IAU. 2006-08-24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ "Latest Published Data". Minor Planet Center. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ When did the asteroids become minor planets? Archived 2009-08-25 at the Wayback Machine, James L. Hilton, Astronomical Information Center, United States Naval Observatory. Accessed May 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Planet, asteroid, minor planet: A case study in astronomical nomenclature, David W. Hughes, Brian G. Marsden, Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 10, #1 (2007), pp. 21–30. Bibcode:2007JAHH...10...21H

- ^ Mike Brown, 2012. How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming

- ^ a b c "Asteroid Archived 2009-10-28 at the Wayback Machine", MSN Encarta, Microsoft. Accessed May 5, 2008. Archived 2009-11-01.

- ^ Questions and Answers on Planets Archived 2020-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, additional information, news release IAU0603, IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes, International Astronomical Union, August 24, 2006. Accessed May 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Minor Planet Statistics – Orbits And Names". Minor Planet Center. 28 October 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ JPL. "How Many Solar System Bodies". JPL Solar System Dynamics. NASA. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ "Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (1)-(5000)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ https://www.wgsbn-iau.org/files/Bulletins/V005/WGSBNBull_V005_025.pdf

- ^ "Near-Earth Object groups", Near Earth Object Project, NASA, archived from the original on 2002-02-02, retrieved 2011-12-24

- ^ Connors, Martin; Wiegert, Paul; Veillet, Christian (July 2011), "Earth's Trojan asteroid", Nature, 475 (7357): 481–483, Bibcode:2011Natur.475..481C, doi:10.1038/nature10233, PMID 21796207, S2CID 205225571

- ^ Trilling, David; et al. (October 2007), "DDT observations of five Mars Trojan asteroids", Spitzer Proposal ID #465: 465, Bibcode:2007sptz.prop..465T

- ^ "2020 XL5". Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Horner, J.; Evans, N.W.; Bailey, M. E. (2004). "Simulations of the Population of Centaurs I: The Bulk Statistics". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 354 (3): 798–810. arXiv:astro-ph/0407400. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.354..798H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08240.x. S2CID 16002759.

- ^ Neptune trojans, Jupiter trojans

- ^ "Running Tallies – Minor Planets Discovered". IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Dr. David Jewitt. "Classical Kuiper Belt Objects". David Jewitt/UCLA. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz (10 June 2012). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (6 ed.). Springer. p. 15. ISBN 9783642297182.

- ^ "Naming Astronomical Objects". International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ NASA JPL Small-Body Database Browser on 1927 Suvanto

- ^ NASA JPL Small-Body Database Browser on 96747 Crespodasilva

- ^ Staff (November 28, 2000). "Lucy Crespo da Silva, 22, a senior, dies in fall". Hubble News Desk. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ 谷 'valley' being a common abbreviation of 穀 'grain' that would be formally adopted with simplified Chinese characters.

- ^ "Division III Commission 15 Physical Study of Comets & Minor Planets". International Astronomical Union (IAU). September 29, 2005. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ "Physical Properties of Asteroids". Planetary Data System. Planetary Science Institute.

- ^ "The Near-Earth Asteroids Data Base". Archived from the original on 2014-08-21. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ Grant, Heiken; David, Vaniman; Bevan M, French (1991). Lunar sourcebook: a user 's guide to the moon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 753.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ David, Morrison (1977). "Asteroid sizes and albedos". Icarus. 31 (2): 185–220. Bibcode:1977Icar...31..185M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(77)90034-3.

- ^ Xiao, Long (2013). Planetary Geology. Geological Press. pp. 346–347.

- ^ HOUSEN, K R; HOLSAPPLE, K A (2003). "Impact cratering on porous asteroids". Icarus. 163 (1): 102–109. Bibcode:2003Icar..163..102H. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00024-1.

- ^ ZOU, X; LI, C; LIU, J (2014). "The preliminary analysis of the 4179 Toutatis snapshots of the Chang'e-2 flyby". Icarus. 229: 348–354. Bibcode:2014Icar..229..348Z. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.002.

- ^ KROHN, K; JAUMANN, R; STEPHAN, K (2012). "Geologic mapping of the Av-12 sextilia quadrangle of asteroid 4 Vesta". EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts: 8175. Bibcode:2012EGUGA..14.8175K.

- ^ MAHANEY, W C; KALM, V; KAPRAN, B (2009). "Clast fabric and mass wasting on minor planet 25143-Itokawa: correlation with talus and other periglacial features on Earth". Sedimentary Geology: 44–57. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2009.04.007.

- ^ BUCZKOWSKI, D; WYRICK, D; IYER, K (2012). "Largescale troughs on Vesta: a signature of planetary tectonics". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (18): 205–211. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3918205B. doi:10.1029/2012GL052959. S2CID 33459478.

- ^ COLWELL, J E; GULBIS, A A; HORÁNYI, M (2005). "Dust transport in photoelectron layers and the formation of dust ponds on Eros". Icarus. 175 (1): 159–169. Bibcode:2005Icar..175..159C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.11.001.

- ^ CLARK, B E; HAPKE, B; PIETERS, C (2002). Asteroid space weathering and regolith evolution. p. 585. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1v7zdn4.44.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ NOGUCHI, T; NAKAMURA, T; KIMURA, M (2011). "Incipient space weathering observed on the surface of Itokawa dust particles". Science. 333 (6046): 1121–1125. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1121N. doi:10.1126/science.1207794. PMID 21868670. S2CID 5326244.

- ^ SUGITA, S; HONDA, R; MOROTA, T (2019). "The geomorphology, color, and thermal properties of Ryugu: implications for parent-body processes". Science. 364 (6437): 252. Bibcode:2019Sci...364..252S. doi:10.1126/science.aaw0422. PMC 7370239. PMID 30890587.

- ^ WEISS, B P; ELKINS-TANTON, L; BERDAHL, J S (2008). "Magnetism on the angrite parent body and the early differentiation of planetesimals". Science. 322 (5902): 713–716. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..713W. doi:10.1126/science.1162459. PMID 18974346. S2CID 206514805.

- ^ BRYSON, J F; HERRERO-ALBILLOS, J; NICHOLS, C I (2015). "Long-lived magnetism from solidification-driven convection on the pallasite parent body". Nature. 517 (7535): 472–475. Bibcode:2015Natur.517..472B. doi:10.1038/nature14114. PMID 25612050. S2CID 4470236.

- ^ IP, W H; HERBERT, F (1983). "On the asteroidal conductivities as inferred from meteorites". The Moon and the Planets. 28 (1): 43–47. Bibcode:1983M&P....28...43I. doi:10.1007/BF01371671. S2CID 120019436.

- ^ KIVELSON, M; BARGATZE, L; KHURANA, K (1993). "Magnetic field signatures near Galileo 's closest approach to Gaspra". Science. 261 (5119): 331–334. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..331K. doi:10.1126/science.261.5119.331. PMID 17836843. S2CID 29758009.

- ^ RICHTER, I; BRINZA, D; CASSEL, M (2001). "First direct magnetic field measurements of an asteroidal magnetic field: DS1 at Braille". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (10): 1913–1916. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.1913R. doi:10.1029/2000GL012679. S2CID 121432765.

- ^ RICHTER, I; AUSTER, H; GLASSMEIER, K (2012). "Magnetic field measurements during the ROSETTA flyby at asteroid (21) Lutetia" (PDF). Planetary and Space Science. 66 (1): 155–164. Bibcode:2012P&SS...66..155R. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2011.08.009. S2CID 56091003.

External links

[edit]Minor planet

View on GrokipediaDefinition and History

Definition and Classification

A minor planet is defined as a natural celestial object in direct orbit around the Sun that is neither classified as a planet nor a comet. This encompasses a wide range of small Solar System bodies, excluding satellites of planets, comets (which exhibit volatile sublimation and cometary activity), and meteoroids (small fragments, typically less than 1 meter in diameter). The term is formally used by the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center (MPC) to catalog such objects, which must lack the characteristics of comets, such as a coma or tail, to qualify.[8] The 2006 IAU resolutions established broader categories for Solar System bodies, defining planets as those that orbit the Sun, achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly spherical shape), and clear their orbital neighborhoods. Dwarf planets meet the first two criteria but not the third, while small Solar System bodies include all remaining objects orbiting the Sun except satellites—a category that supersedes the older "minor planet" terminology but is still employed by the MPC for non-cometary bodies. Dwarf planets, such as Pluto and Ceres, are thus a specialized subset of minor planets, distinguished by their rounded shapes due to self-gravity despite not dominating their orbits.[9] Minor planets are broadly subclassified based on their orbital locations and compositions: asteroids primarily occupy the inner Solar System (e.g., the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, composed mainly of rocky or metallic materials); centaurs reside in unstable orbits between Jupiter and Neptune, showing hybrid asteroid-comet traits; and trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) lie beyond Neptune, often icy in composition. These classifications aid in understanding their origins and dynamics, with dwarf planets like Pluto exemplifying TNOs that achieve hydrostatic equilibrium. The term "minor planet" originated in the 19th century to describe these newly discovered bodies beyond the eight major planets, with early usage appearing in astronomical ephemerides around 1835.[10]Historical Discovery and Terminology

The first minor planet, Ceres, was discovered on January 1, 1801, by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi at the Palermo Astronomical Observatory while compiling a star catalog.[11] Initially classified as the eighth planet in the solar system, fitting between Mars and Jupiter, Ceres was soon followed by the discoveries of Pallas in 1802 by Heinrich Olbers, Juno in 1804 by Karl Harding, and Vesta in 1807 by Olbers again.[12] These objects were also regarded as planets due to their positions in the expected orbit of a hypothesized missing planet, though their small sizes and irregular paths raised early questions about their status.[13] As more such bodies were identified, astronomers sought new terminology to distinguish them from major planets. In 1802, William Herschel proposed the term "asteroid" (meaning star-like) for Ceres and Pallas, emphasizing their point-like appearance compared to the disk-like planets, a suggestion rooted in his observations of their dissimilarities.[10] However, with dozens more discovered between the mid-1840s and 1850s—bringing the total to 23 by the end of 1852—the planetary classification became untenable, leading to the widespread adoption of "minor planet" in the 1850s across Europe, including official use in the United Kingdom, Germany ("kleiner Planet"), and France ("petite planète").[14] This shift reflected the growing recognition of these objects as a distinct population rather than isolated planetary fragments.[13] Key milestones in the 19th century included systematic surveys at observatories worldwide, such as Harvard College Observatory's Boyden Station in Peru, established in 1889, which contributed to photographic observations of southern skies and aided in detecting faint minor planets. These efforts, building on visual searches that had identified the first few hundred asteroids by century's end, expanded the catalog dramatically. In the 20th century, the discovery of Pluto in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh at Lowell Observatory marked the first recognized trans-Neptunian object (TNO), initially classified as the ninth planet but later understood as part of a larger TNO population.[15] This prompted further searches, though additional TNOs were not confirmed until 1992, highlighting the challenges of observing beyond Neptune.[16] The evolution of minor planet catalogs began with inclusions in early astronomical almanacs, such as the U.S. Nautical Almanac, which listed asteroids alongside planets from the 1850s onward.[17] By the early 20th century, centralized efforts emerged, culminating in the establishment of the Minor Planet Center (MPC) in 1947 under the International Astronomical Union, with Paul Herget as its first director at the Cincinnati Observatory.[18] The MPC standardized designations and publications, issuing Minor Planet Circulars to track discoveries and orbits systematically.[19]Populations and Classification

Main Asteroid Belt

The main asteroid belt is an annular region in the Solar System located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, with semi-major axes ranging from approximately 2.1 to 3.3 AU. This zone contains over one million known asteroids larger than 1 km in diameter, representing the primary reservoir of rocky minor planets and accounting for a significant portion of the belt's total mass.[20][3] Asteroids in the main belt are classified primarily by their spectral types, which reflect surface compositions and provide insights into their formation and evolutionary history. The dominant C-type (carbonaceous) asteroids, comprising over 75% of the population, are rich in carbon, silicates, and possibly water-bearing minerals, and are more prevalent in the outer belt beyond about 2.5 AU, suggesting origins from cooler regions of the early Solar System. S-type (silicaceous) asteroids make up about 17%, featuring stony compositions with silicates and metals, and dominate the inner belt closer to 2.2 AU, indicating formation nearer the Sun where higher temperatures inhibited volatiles. M-type (metallic) asteroids constitute roughly 7%, primarily composed of iron and nickel, and are concentrated around 2.7 AU, likely remnants of differentiated parent bodies that underwent melting and core formation. These compositional gradients imply a radial stratification inherited from the protoplanetary disk, with dynamical mixing playing a role in their current distribution.[4][21][22] The size distribution of main belt asteroids follows a power-law relation, where the cumulative number of objects with diameters greater than D, denoted N(>D), scales as ∝ D^{-2.5} for diameters exceeding a few kilometers; this steep slope indicates a collisional equilibrium shaped by impacts over billions of years. The largest object is Ceres, a dwarf planet with a diameter of 940 km, which alone comprises about one-third of the belt's total mass and exemplifies the transition from smaller fragments to more intact bodies. Smaller asteroids, down to sub-kilometer sizes, deviate from this power law due to observational biases and ongoing fragmentation, but the relation holds for the dominant mid-sized population.[23][24][25] Notable features within the belt include Kirkwood gaps, regions depleted of asteroids at specific semi-major axes, such as 2.5 AU (3:1 resonance), 2.82 AU (5:2), and 3.27 AU (2:1), resulting from gravitational perturbations by Jupiter that destabilize orbits and eject material over time. These gaps highlight the belt's dynamical structure, with resonances clearing pathways for asteroid transport. In contrast, asteroid families like the Flora and Eunomia groups represent clusters of objects sharing similar orbits, formed by catastrophic collisions of larger parent bodies; the Flora family, for instance, spans the inner belt and includes hundreds of S-type members from a disruption event estimated at 1-2 billion years ago, while Eunomia's family in the middle belt features a mix of types from a similar collisional origin. Such families provide direct evidence of the belt's violent history, with fragments dispersing but retaining dynamical signatures.[26][27]Near-Earth and Trojan Populations

Near-Earth objects (NEOs) are minor planets whose orbits bring them into close proximity with Earth, specifically with perihelion distances less than 1.3 AU. They are classified into dynamical subgroups based on their orbital characteristics relative to Earth's orbit: Atens have semimajor axes less than 1 AU and cross Earth's orbit (e.g., 2062 Aten); Apollos have semimajor axes greater than 1 AU but perihelia under 1.017 AU, also crossing Earth's orbit (e.g., 1862 Apollo); Amors have perihelia between 1.017 and 1.3 AU, approaching but not crossing Earth's orbit (e.g., 1221 Amor); and Atiras (or interior Earth objects, IEOs) have aphelia less than 0.983 AU, entirely within Earth's orbit (e.g., 163693 Atira). As of November 2025, approximately 40,000 NEOs are known, predominantly asteroids with a small fraction being comets.[28][6] Among NEOs, potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs) represent a subset posing collision risks, defined as those with a minimum orbit intersection distance (MOID) to Earth of 0.05 AU or less and an absolute magnitude brighter than H=22.0, corresponding to diameters roughly exceeding 140 meters. There are currently 2,349 known PHAs, with objects larger than 1 km considered capable of global impacts if they collide with Earth. NEOs primarily originate from the main asteroid belt, where gravitational resonances with planets or the thermal Yarkovsky effect—caused by asymmetric radiation from sunlight—gradually alter their semimajor axes, injecting them into Earth-crossing orbits over millions of years.[29][30][31] Trojan asteroids are minor planets that share the orbit of a planet, librating around its L4 or L5 Lagrange points in stable tadpole or horseshoe configurations. Jupiter hosts the largest known Trojan population, with over 15,300 discovered as of October 2025, distributed unevenly between the "Greek" camp ahead at L4 (about two-thirds) and the "Trojan" camp trailing at L5 (e.g., 624 Hektor in the L4 swarm). Smaller Trojan contingents exist for other planets, including Earth, Mars, Uranus, and Neptune. Unlike NEOs, Jupiter Trojans are thought to have been captured from the outer Solar System during the dynamical instability of the giant planets in the early Solar System, preserving primitive compositions akin to Kuiper Belt objects.[32][33][34]Trans-Neptunian and Centaur Objects

Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) are icy minor planets whose orbits lie beyond Neptune's average distance of approximately 30 AU from the Sun. These objects form the outermost known populations of the Solar System and are primarily composed of frozen volatiles such as water, methane, and ammonia. The Kuiper belt, extending from about 30 to 50 AU, hosts the majority of TNOs and is divided into classical and resonant subpopulations based on their dynamical interactions with Neptune.[35] Classical TNOs, also known as cubewanos, occupy non-resonant orbits with low eccentricities (typically e < 0.2) and semimajor axes between 40 and 50 AU. They are further subdivided into "cold" and "hot" populations distinguished by orbital inclination: cold classical TNOs have low inclinations (i < 5°), indicating a more primordial, dynamically stable group, while hot classical TNOs exhibit higher inclinations (i > 5°), suggesting greater past perturbations.[36] Resonant TNOs, in contrast, are trapped in mean-motion resonances with Neptune, such as the 2:3 resonance occupied by Plutinos, which stabilize their orbits against close encounters with the planet. The Plutino population, named after Pluto, represents a significant fraction of resonant objects and exemplifies how Neptune's gravitational influence sculpts the outer Solar System.[37] Beyond the classical Kuiper belt lies the scattered disk, a dynamically excited population extending past 50 AU with high orbital eccentricities (e > 0.2) and perihelia greater than 30 AU. These objects are believed to have been perturbed by Neptune into more distant, unstable orbits, resulting in a broader distribution that may reach up to hundreds of AU. The scattered disk serves as a reservoir for objects that can evolve into Centaurs through inward scattering.[38] Centaurs are a transitional class of minor planets with unstable orbits crossing those of the giant planets, typically between 5 and 30 AU from the Sun. Originating from the scattered disk or outer Kuiper belt, Centaurs act as a dynamical bridge between TNOs and inner Solar System populations, with lifetimes of only a few million years before being ejected or evolving into short-period comets. Some Centaurs display comet-like activity due to sublimation of surface ices as they approach warmer regions; for example, 2060 Chiron exhibits periodic outbursts of dust and gas.[39] As of late 2025, approximately 3,000 TNOs with diameters larger than 50 km have been discovered, though this represents only a small fraction of the estimated total population exceeding 100,000 such objects. Among them, 136199 Eris stands out as the largest known TNO, with a diameter of 2,326 ± 12 km, slightly smaller than Pluto but more massive due to its higher density. A subset of TNOs qualifies as dwarf planets under International Astronomical Union criteria, including Eris and Pluto, which share similar icy compositions but distinct orbital histories.[41] A distinct group within the TNO population consists of detached objects, characterized by high perihelia (q > 40 AU) and large semimajor axes, placing them beyond Neptune's resonant influence. These orbits are difficult to explain through standard planet formation models and have been hypothesized to result from the gravitational shepherding of a distant, undiscovered Planet Nine, a potential super-Earth-mass body that could cluster their arguments of perihelion. Observations of such objects, including Sedna-like TNOs with perihelia exceeding 60 AU, continue to test this hypothesis.[42][43]Other Minor Planet Groups

Damocloids represent a distinctive group of minor planets characterized by highly eccentric, long-period orbits reminiscent of Halley-type or long-period comets, yet distinguished by their lack of detectable cometary activity, suggesting they are extinct comet nuclei depleted of volatiles.[44] These objects typically exhibit retrograde orbits, with inclinations often exceeding 90 degrees relative to the ecliptic, and semi-major axes greater than 7 AU, placing them dynamically in the scattered disk or inner Oort cloud regions.[44] The prototype, (5335) Damocles, discovered in 1991, exemplifies this class with its eccentric orbit (eccentricity ~0.9) and retrograde motion, spanning from near-Earth distances at perihelion to beyond Saturn at aphelion.[45] As of early 2025, approximately 316 damocloids are known, representing less than 0.01% of the over 1.47 million cataloged minor planets, underscoring their rarity.[46] Some damocloids blur the boundary with active comets, as seen in cases like 174P/Echeclus, a centaur object initially classified as a minor planet in 2000 before exhibiting a sudden outburst of cometary activity in 2005, producing a dust coma at 13 AU from the Sun.[47] This event, with a dust production rate of 200-400 kg/s, highlights the transitional nature of such bodies, where dormant nuclei may reactivate under perihelion heating, challenging strict dichotomies between asteroids and comets.[48] Despite occasional activity, inactive damocloids are formally designated as minor planets under International Astronomical Union (IAU) criteria, provided no sustained coma or tail is observed.[8] Interstellar objects form another exceptional category, originating from outside the Solar System and temporarily passing through on hyperbolic trajectories. The first confirmed example, 1I/'Oumuamua, was discovered in October 2017 by the Pan-STARRS telescope, exhibiting a hyperbolic trajectory (eccentricity >1) with an inbound velocity excess of 26 km/s relative to the Sun, confirming its extrasolar provenance.[49] This cigar-shaped, rocky body, approximately 100-1000 m long, showed no cometary outgassing but anomalous non-gravitational acceleration, possibly from outgassing of exotic ices, and was classified as an interstellar minor planet with the "I" prefix.[49][50] The second, 2I/Borisov, discovered in August 2019, displayed clear cometary activity with a cyanogen-rich coma and a hyperbolic orbit (eccentricity 3.36), and was classified as an interstellar comet.[51] It fragmented near perihelion in 2020, revealing a composition akin to Solar System comets. In July 2025, the third interstellar object, comet 3I/ATLAS, was discovered, showing cometary jets and a hyperbolic path, further expanding our knowledge of extrasolar visitors.[52] To date, these three interstellar objects comprise a minuscule fraction—far less than 0.0001%—of known minor planet populations, with estimates suggesting thousands may traverse annually but evade detection due to high speeds and faintness.[51][53] Vulcanoids constitute a hypothetical population of minor planets in stable, low-eccentricity orbits interior to Mercury, between approximately 0.18 and 0.4 AU from the Sun, potentially remnants of the early Solar System's protoplanetary disk spared from Mercury's formation.[54] Predicted to be small, with diameters limited to under 6 km to avoid detection and tidal disruptions, these bodies would experience intense solar heating, possibly leading to darkened surfaces and volatile loss.[55] Extensive searches, including coronagraphic observations from space missions like SOHO/LASCO, have yielded no confirmed detections, establishing upper limits of fewer than 42,000 objects larger than 1 km in diameter across the zone.[55] If extant, vulcanoids would represent an elusive, undetected subset of minor planets, likely numbering in the thousands at sub-kilometer scales but comprising negligible overall population fractions due to their confined dynamical niche.[54]Naming and Designation

Provisional Designation System

The provisional designation system assigns temporary identifiers to newly discovered minor planets to facilitate tracking and communication among astronomers until a permanent numerical designation can be granted. Managed by the Minor Planet Center (MPC), an official body of the International Astronomical Union (IAU), this system ensures unique labels for objects whose orbits cannot immediately be linked to previously known bodies.[56] The standard format for a provisional designation consists of the four-digit year of the first observation, followed by a space, a half-month letter indicating the period of discovery (A through H for January to April, a through h for May to August, and additional letters up to Y, excluding I to avoid confusion with the number 1), and then a sequential identifier comprising an order letter (A–Z, excluding I) for the discovery sequence within that half-month, optionally followed by a number if more than 25 objects are designated in the same combination (e.g., 2023 AB1, where "A" denotes the first half of January 2023, "B" the second discovery in that period, and "1" the first excess beyond 25). The designations reset at the start of each half-month, allowing for systematic cataloging without overlap. This unpacked format, used since 1925, replaced earlier "old-style" systems that employed simpler year-letter combinations (e.g., 1892 A) or packed letters for high-volume discoveries before 1925, which became insufficient as discovery rates increased.[57] Provisional designations are assigned by the MPC once an object's orbit can be reliably computed, typically requiring observations on at least two separate nights to confirm it is not a known object or spurious detection, though in practice 3–4 observations spanning several nights are often needed for initial orbit determination. This process supports the cataloging of approximately 25,000 new minor planet discoveries each year as of 2025, enabling global collaboration on follow-up observations while the object remains provisional—pending accumulation of sufficient data, such as observations over one or more oppositions, for permanent numbering. Since 1995, the system has been extended to include provisional designations for satellites of minor planets, appending a letter (starting with A) to the primary's designation (e.g., 2023 AB1A for the first satellite of 2023 AB1), allowing integrated tracking of binary or multi-component systems.[57]Numbering Process

The numbering process assigns a permanent numerical designation to a minor planet once its orbit has been reliably determined through sufficient observational data, enabling accurate long-term predictions. The Minor Planet Center (MPC), the official bureau of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) hosted by the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, oversees this procedure by collecting and analyzing astrometric observations from observatories worldwide.[6][58] For an object to receive a number, its orbit must typically be secured by observations spanning at least four oppositions for main-belt asteroids, or three oppositions for near-Earth objects, ensuring low orbital uncertainty; in practice, this often corresponds to data over at least 1,000 days with the semi-major axis uncertainty below AU. This multi-opposition requirement confirms the object's path independently of discovery apparition perturbations and distinguishes it from known bodies. The MPC computes orbits using these observations, primarily from survey networks like Pan-STARRS, which provide high-volume, precise measurements essential for refining elements such as semi-major axis, eccentricity, and inclination.[59][60] Once criteria are met, the MPC assigns the next sequential integer in parentheses before the provisional designation, beginning with (1) Ceres in 1801; as of November 2025, approximately 875,000 minor planets have been numbered, reflecting advances in survey capabilities. Numbering occurs via publication in the Minor Planet Circulars, formalizing the object's status in the IAU registry.[6][61][62] Exceptions to standard criteria apply for dynamically interesting objects, such as near-Earth asteroids, which may be numbered after only two oppositions if uncertainty is sufficiently low due to frequent observability. Many numbered objects remain unnamed indefinitely, retaining their numerical designation alone, as exemplified by (99942) Apophis, a potentially hazardous asteroid identified in 2004. Historical objects predating modern provisional systems have received retroactive numbers without altering their established names, ensuring comprehensive cataloging.[59]Official Naming Conventions

Once a minor planet has been assigned a permanent number by the Minor Planet Center (MPC), the discoverer has the right to propose an official name, typically within 10 years of the numbering date.[59] The proposal is submitted to the MPC along with a short citation explaining the name's significance, after which it is forwarded to the Working Group for Small Bodies Nomenclature (WGSBN) of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) for review.[64] The WGSBN, comprising up to 15 members, evaluates the proposal through a voting process requiring at least six affirmative votes with no more than five against for approval; approved names are then published in the WGSBN Bulletin and become official.[64] This procedure ensures that naming follows established scientific and cultural protocols, with the discoverer retaining naming rights as a recognition of their contribution, though co-discoverers may share this privilege in certain cases.[59] Naming traditions emphasize mythological figures from various cultures, including ancient, modern, or even fictional mythologies, to maintain a cohesive and evocative nomenclature; for instance, the near-Earth asteroid (433) Eros draws from the Greek god of love.[64] Names must be unique, not duplicating those of satellites, constellations, or exoplanets, and are limited to a single word of up to 16 characters in modern Latin script, often including diacritics for non-English origins.[64] Political, military, or religious names are prohibited until at least 100 years after the death of the individual or the event in question, and commercial endorsements, pet names, acronyms, or purely numerical designations are generally discouraged to preserve the neutrality and scholarly tone of the catalog.[64] Exceptions to the one-word rule may occur for thematic reasons, such as the 17-character name (4015) Wilson-Harrington for a lost comet-asteroid hybrid, but such cases are rare and require strong justification.[64] Gender and linguistic aspects of names reflect mythological conventions, with masculine or feminine forms assigned based on the figure's traditional gender in the source culture, promoting balance in representation across genders and geographies.[64] Multilingual names are accepted if romanized into Latin script, allowing for global diversity while ensuring accessibility; for example, names honoring discoverers or scientists may deviate from strict mythology but must still adhere to propriety standards.[64] Special orbital classes impose additional thematic guidelines: near-Earth objects avoid names tied to creation or underworld myths to prevent sensitive connotations, while Jupiter Trojans favor figures from the Trojan War or Olympian pantheons, and Plutinos draw from underworld deities.[64] These conventions, formalized in the WGSBN's guidelines adopted on December 20, 2021 and updated in February 2025 (Version 1.1), build on historical practices while adapting to contemporary inclusivity, ensuring the minor planet catalog remains a culturally rich yet rigorously vetted resource.[64]Orbital Dynamics

Orbital Characteristics and Resonances

Minor planets are characterized by their orbital elements, which describe the shape, orientation, and position of their orbits around the Sun in a two-body approximation dominated by solar gravity. These Keplerian elements include the semi-major axis , which defines the size of the orbit; the eccentricity , which measures its deviation from circularity; the inclination , which indicates the tilt relative to the ecliptic plane; the longitude of the ascending node , specifying the orientation of the orbital plane; the argument of perihelion , denoting the angle from the ascending node to the perihelion; and the mean anomaly , which tracks the body's position along the orbit at a given epoch.[65] For main-belt minor planets, typical values span semi-major axes from approximately 2.1 to 3.3 AU, eccentricities generally below 0.3 (with averages around 0.15), and inclinations up to about 25° (averaging 10°).[66][67] Orbital perturbations from major planets, particularly Jupiter, introduce deviations from pure Keplerian motion, leading to resonances that significantly influence minor planet distributions. Mean-motion resonances occur when the orbital periods of a minor planet and a planet are in a simple integer ratio, expressed as , where and are integers, corresponding to the mean motions . The semi-major axis for such a resonance is given by , where AU is Jupiter's semi-major axis; for example, the 3:1 resonance places minor planets at about 2.5 AU.[68] These resonances can trap minor planets in stable librating orbits or destabilize them through chaotic evolution. Secular resonances, involving the alignment of apsidal (precession of perihelia) or nodal (precession of ascending nodes) rates, further modulate long-term orbital evolution, such as the apsidal resonance where the minor planet's perihelion precession rate matches that of Saturn.[69] Prominent mean-motion resonances with Jupiter sculpt the main asteroid belt, creating Kirkwood gaps—depletions in minor planet density at locations like the 3:1 (~2.50 AU), 5:2 (~2.82 AU), 7:3 (~2.95 AU), and 2:1 (Hecuba gap at ~3.27 AU) resonances. These gaps form primarily through chaotic ejection, where overlapping resonant perturbations drive diffusive changes in eccentricity and inclination, eventually ejecting minor planets from the belt on timescales of millions of years via close encounters with planets.[70] In contrast, certain resonances support stable populations; the Hilda group resides in the 3:2 resonance at ~4 AU, where minor planets librate stably due to the geometry of the resonant Hamiltonian, avoiding chaotic diffusion for billions of years.[71] Observational data on these orbital characteristics are compiled in the Minor Planet Center's MPCORB database, which provides osculating Keplerian elements derived from astrometric observations for over 1 million minor planets.[72] Perturbations by the planets are incorporated through numerical integration of the equations of motion, using methods like symplectic integrators to model gravitational influences over extended periods and predict future positions with high accuracy.[73]Dynamical Evolution and Stability

The dynamical evolution of minor planets is profoundly influenced by non-gravitational forces, notably the Yarkovsky effect, which arises from the anisotropic thermal radiation of rotating bodies. This effect generates a recoil thrust that perturbs orbits, primarily causing a secular drift in the semi-major axis for asteroids smaller than approximately 30-40 km in diameter. For kilometer-sized bodies, the typical drift rate is on the order of AU per million years, with the direction depending on the sense of rotation (prograde or retrograde).[74] The non-gravitational acceleration due to this effect is given by where is the thermal force from re-emitted radiation, is the speed of light, and is the body's mass; this acceleration scales inversely with size, making smaller objects more susceptible to orbital migration over gigayear timescales.[74] Chaotic diffusion further drives orbital instability, particularly in mean-motion resonances where overlapping perturbations from planets lead to exponential divergence of trajectories. In such resonant zones, Lyapunov times—the characteristic timescale for chaos to manifest—are typically around years, enabling slow but inexorable diffusion in semi-major axis and eccentricity.[75] For trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), the Nice model illustrates early dynamical scattering during planetary migration, where giant planet interactions destabilized the outer disk, ejecting many planetesimals and reshaping the TNO population through resonant capture and chaotic transport.[76] Collisions among minor planets also play a key role in evolution, with lifetimes for main-belt asteroids larger than 10 km estimated at about 100 million years, governing the erosion of populations and the progressive steepening of size-frequency distributions as larger bodies fragment into smaller debris.[77] Over Solar System timescales, these processes culminate in the long-term fate of minor planets, where dynamical instabilities lead to ejection into interstellar space or collision with planets. Symplectic integrators, such as the SWIFT code, enable efficient simulations of these N-body interactions, revealing that a significant fraction of small bodies in the main belt and scattered disk are removed via planetary close encounters over billions of years, depleting the primordial populations.[78]Physical Properties

Size, Shape, and Mass

Minor planets exhibit a wide range of sizes, spanning from a few meters to nearly 950 kilometers in diameter. The smallest detected minor planets, such as those observed by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope in the main asteroid belt, measure as little as 10 meters across, though most numbered objects are larger due to observational biases favoring brighter, bigger bodies. At the upper end, Ceres holds the distinction as the largest known minor planet in the inner Solar System, with an equatorial diameter of 939.4 kilometers determined from spacecraft imaging and radar data. Diameters for these bodies are primarily estimated through methods including radar ranging for near-Earth objects, stellar occultations that reveal silhouettes during alignments with background stars, and infrared thermal modeling that infers sizes from emitted heat based on assumed albedos and rotational properties. The shapes of minor planets are predominantly irregular for those with diameters less than approximately 300 kilometers, shaped by rapid rotation, low self-gravity, and frequent collisions that prevent relaxation into equilibrium forms. Smaller bodies often resemble elongated rubble piles or peanuts, while even some larger ones like Vesta (diameter ~525 km) display significant deviations from sphericity. In contrast, Ceres achieves a nearly spherical oblate shape due to sufficient mass for hydrostatic equilibrium, with oblateness quantified by gravitational harmonics such as the J2 moment derived from orbital data. A notable example is the near-Earth asteroid Bennu, which exhibits a distinctive spinning-top morphology with a pronounced equatorial ridge, as revealed by high-resolution imaging from NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission. Masses of minor planets are challenging to measure directly but are inferred from gravitational influences on nearby objects or spacecraft. For instance, the Dawn spacecraft's trajectory perturbations yielded Vesta's mass as (2.59076 ± 0.00001) × 10^{20} kg, enabling density calculations when combined with volume estimates. Binary minor planet systems provide another key method, where mutual orbital periods and separations allow computation of the combined mass via Kepler's third law; examples include the S-type asteroid (6178) 1986 DA, with a mass derived from its satellite's 17.4-hour orbit. Resulting bulk densities typically fall between 1 and 3 g/cm³, varying with taxonomic class—lower for porous, icy outer Solar System objects and higher for compact, metallic inner belt asteroids—reflecting internal structures from primitive aggregates to differentiated bodies. The distribution of minor planet sizes follows a power-law form, with the cumulative number of objects larger than a given diameter D (>1 km) described by the relation where C is a constant, indicating a steep increase in the abundance of smaller bodies consistent with collisional evolution models. This distribution underscores the dominance of sub-kilometer objects, though observational incompleteness affects counts below ~100 meters.Composition and Density

Minor planets, also known as asteroids, exhibit diverse compositions inferred primarily through reflectance spectroscopy in the visible and near-infrared wavelengths from 0.4 to 2.5 μm. The Bus-DeMeo taxonomy, an extension of earlier systems like Tholen and Bus, classifies these bodies into spectral types based on absorption features indicative of mineralogy, such as silicates, carbonaceous materials, and metals. For instance, the Xc subtype represents carbonaceous-rich objects with low albedo and flat spectra, while S-types show prominent olivine and pyroxene bands around 1 μm and 2 μm.[79][80] The primary compositional categories include primitive, differentiated, and metallic types, each linked to distinct density regimes that reflect their formation and evolutionary histories. Primitive minor planets, akin to C-chondrites, dominate the outer main belt and are rich in volatiles and organics, yielding bulk densities around 1.5–2.0 g/cm³ due to high porosity and hydrated silicates.[81] In contrast, differentiated S-type objects, resembling ordinary chondrites with stony-iron compositions, exhibit densities near 2.7 g/cm³, as seen in asteroid (433) Eros, though macroporosity can lower effective values.[82] Metallic M-types, potentially cores of differentiated planetesimals, are iron-nickel rich and expected to have densities up to 5 g/cm³, but measurements for bodies like (16) Psyche indicate 3.0–4.0 g/cm³ owing to rubble-pile structures.[83] Volatiles such as water ice are prevalent in outer-belt primitive minor planets and Centaurs, detected via spectral absorptions near 3 μm, suggesting subsurface reservoirs that may outgas under certain conditions. Organics, including amino acids, have been directly sampled from the C-type asteroid (162173) Ryugu by the Hayabusa2 mission, which returned material in 2020 revealing over 20 amino acid varieties, many rare on Earth, embedded in a hydrated matrix.[84][85] Bulk densities are derived by combining mass estimates from gravitational perturbations on nearby objects with volumes from radar, spacecraft imaging, or lightcurve-based shape models. For example, asteroid (25143) Itokawa, an S-type rubble pile visited by Hayabusa, has a bulk density of 1.9 ± 0.13 g/cm³, implying ~40% macroporosity and a loosely bound structure of boulders and regolith. Such low-density anomalies highlight the role of collisional evolution in creating porous aggregates rather than monolithic bodies.[86][87]Rotation and Thermal Properties

Rotation periods of minor planets are primarily determined through photometric lightcurve analysis, which reveals periodic variations in brightness due to the irregular shapes of these bodies. The majority of asteroids exhibit rotation periods ranging from 2 to 20 hours, with a peak distribution around 5 to 10 hours for main-belt objects larger than 10 km.[88] Smaller asteroids, particularly those under 10 km in diameter, display a broader distribution, including excesses of both slow rotators (periods exceeding 20 hours) and fast rotators (periods under 2 hours), often associated with binary systems where the primary's rotation is synchronized with the orbital motion of the secondary.[88] Tumbling or non-principal axis rotation is observed in a small fraction of cases, such as among very small near-Earth objects, resulting from past collisions or torques that excite complex spin states.[88] A key constraint on rotation is the spin barrier, approximately 2.2 hours, which limits the fastest stable spins for cohesive bodies larger than about 200 meters; beyond this rate, centrifugal forces exceed gravitational binding for rubble-pile structures, leading to disruption unless tensile strength is present.[88] This barrier is evident in lightcurve data for main-belt asteroids, with few objects exceeding 11-12 rotations per day unless they are monolithic or binary systems.[88] The YORP (Yarkovsky-O'Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack) effect provides a mechanism for altering these spin rates through asymmetric thermal radiation torques, which accelerate or decelerate rotation depending on the body's shape and orientation.[89] The YORP torque is proportional to the square of the asteroid's radius, the absorbed fraction of solar radiation (1 minus the Bond albedo A), and the incident radiation flux Φ, expressed as .[89] Observations of near-Earth asteroid (101955) Bennu by the OSIRIS-REx mission confirmed YORP-induced spin-up, with the rotation period decreasing at a rate of (3.3 ± 0.7) × 10^{-10} s s^{-1}, consistent with theoretical predictions for its elongated shape.[90] Thermal properties of minor planets are modeled using frameworks like the Near-Earth Asteroid Thermal Model (NEATM), which assumes fast rotation and estimates infrared emission from surface temperatures in radiative equilibrium with sunlight.[91] Under NEATM, the equilibrium temperature at 2 AU, typical for inner main-belt asteroids, is approximately 200 K, accounting for low albedos and diurnal variations that cause subsolar points to reach up to 250 K while nightside regions cool below 100 K.[92] These models are calibrated against infrared observations to derive beaming parameters that adjust for non-zero thermal inertia and phase angles, enabling accurate size and albedo estimates.[91] Pole orientations, which define the spin axis direction, are inferred from adaptive optics (AO) imaging and photometric data, revealing how obliquity influences seasonal heating and radiation effects.[93] Recent analyses using Gaia astrometry have refined pole solutions for thousands of asteroids, showing a tendency toward ecliptic-aligned orientations possibly due to long-term YORP evolution.[94] The pole direction determines the transverse component of Yarkovsky drift, with prograde spins and low obliquities maximizing orbital perturbations from asymmetric photon recoil.[89]Surface and Internal Features

Regolith, Cratering, and Geology

The regolith on minor planets forms a loose, unconsolidated layer of fragmented material primarily generated by hypervelocity impacts from meteoroids and micrometeoroids. This debris covers the surface of airless bodies such as asteroids and trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), protecting underlying bedrock while recording the effects of prolonged exposure to space. On small asteroids like (433) Eros, regolith thickness averages around 10-50 meters, though it can be thinner (1-10 meters) on rubble-pile bodies such as (25143) Itokawa, where impacts excavate and redistribute material to create a dynamic surface layer.[95][96] Space weathering processes, driven by solar wind ion implantation, micrometeorite bombardment, and sputtering, progressively alter the optical properties of regolith over timescales of approximately years. These effects cause spectral darkening and reddening, reducing albedo and shifting reflectance toward longer wavelengths, particularly on S-type asteroids where silicate bands weaken. Such changes create color gradients across surfaces, with fresher, less-weathered exposures appearing brighter and bluer compared to mature regolith. Sample analyses from missions like Hayabusa2 on (162173) Ryugu confirm these alterations occur atop hydrated minerals, linking surface spectra to underlying compositions altered by aqueous processes.[97][98][99] Impact cratering dominates the geological record on minor planets, shaping regolith evolution through excavation, ejecta deposition, and erasure of older features. On small bodies with low gravity, crater populations frequently attain saturation equilibrium, where the density of craters reaches a steady state as new impacts obliterate prior ones, particularly for diameters below 1 km. The depth-diameter relationship in the gravity-dominated regime, applicable to larger craters on these bodies, follows the scaling , where is crater depth, is transient crater diameter, is target density, and is projectile density; this reflects collapse and modification under weak gravitational forces.[100][101][102] Beyond cratering, minor planets exhibit limited but significant geological activity, including cryovolcanism on TNOs and mass wasting on inner solar system asteroids. Cryovolcanic processes, involving the eruption of volatile ices like nitrogen, methane, and ammonia-water slurries, have resurfaced parts of Pluto, as evidenced by dome-like features and flows in regions such as Hayabusa Terra observed by New Horizons; similar activity is inferred on Triton from Voyager 2 imagery of plumes and smooth icy plains. On (4) Vesta, the Dawn mission imaged extensive landslides along steep scarps, such as those near Rheasilvia crater, driven by impact-induced seismicity and low cohesion in the regolith. These processes highlight how internal heat and volatiles influence surface evolution despite the absence of atmospheres or plate tectonics.[103][104][105]Internal Structure and Differentiation

Minor planets exhibit a range of internal structures, from monolithic bodies to loosely bound rubble piles and differentiated protoplanets with layered interiors. Monolithic models describe intact, solid objects with minimal porosity, typically inferred for larger or less dynamically disrupted bodies based on their high densities and lack of evidence for fragmentation.[106] In contrast, the rubble-pile model posits that many minor planets are aggregates of smaller fragments held together by gravity, often resulting from reassembly after collisional breakup, leading to significant macroporosity. For instance, asteroid (25143) Itokawa, observed by the Hayabusa mission, has a bulk density of approximately 1.9 g/cm³, implying a macroporosity of about 40% when compared to its grain density, confirming its rubble-pile nature. Macroporosity is quantified as , where is the bulk density and is the material grain density, and values can reach up to 50% in small asteroids due to void spaces between constituents.[107] Differentiated minor planets feature distinct layers, including a metallic core, silicate mantle, and crust, driven by early heating mechanisms that allowed partial or complete melting. The primary heat source for differentiation in the early solar system was the radioactive decay of short-lived isotope Al, with a half-life of 0.73 million years, which provided sufficient energy for molten interiors in protoplanets formed within the first few million years.[108] Evidence for such structures comes from gravitational and seismic data from spacecraft missions; for example, NASA's Dawn mission measured Vesta's gravity field, revealing a dense iron-rich core with a radius of approximately 110 km, comprising about 25% of the body's mass, surrounded by a mantle and basaltic crust. This layering is further supported by deviations in the moment of inertia factor from the uniform sphere value of , where is mass and is radius; Vesta's factor is lower, around 0.37, indicating central mass concentration due to the dense core.[109] Certain minor planet classes show specialized internal architectures reflective of their compositions and formation environments. M-type asteroids, such as (16) Psyche, are believed to represent exposed metallic cores from differentiated parent bodies, with high radar albedo and metallic spectral signatures suggesting iron-nickel compositions and minimal silicate content.[110] In the outer solar system, trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) often possess thick icy mantles overlying rocky or metallic cores, as inferred from their low bulk densities (around 1-2 g/cm³) and models of volatile-rich accretion beyond the snow line.[111] These diverse structures highlight the role of size, composition, and dynamical history in determining whether minor planets remain undifferentiated rubble or evolve into layered bodies.Observation and Exploration

Ground-Based and Telescopic Observation

Ground-based and telescopic observations have been fundamental to the discovery, cataloging, and characterization of minor planets since the 19th century, enabling astronomers to detect these faint solar system bodies from Earth without spacecraft intervention. These methods rely on optical telescopes equipped with sensitive detectors to scan the night sky, identifying moving objects against the backdrop of stars through repeated imaging. Major surveys have dramatically increased the known population of minor planets, from a few thousand in the early 2000s to over a million today, primarily in the asteroid belt and beyond. Key systematic surveys dominate modern discoveries, particularly for near-Earth objects (NEOs). The Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS), operational since 2010 on Haleakalā, Hawaii, uses a 1.8-meter telescope to conduct all-sky scans in the optical wavelengths, detecting thousands of minor planets annually through difference imaging that highlights transient sources. Similarly, the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS), based at multiple sites including Mount Bigelow Observatory, employs 0.7-meter and 1.5-meter telescopes to monitor the sky, contributing significantly to NEO identification via automated detection algorithms. The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS), with telescopes in Hawaii and Chile, focuses on rapid all-sky coverage to provide early warnings for potential impactors, together with Pan-STARRS and CSS, these surveys account for approximately 90% of all known NEO discoveries as of 2023. These efforts prioritize optical photometry to measure brightness and motion, enabling orbital preliminary orbits for follow-up. Characterization techniques extend beyond discovery to reveal physical properties. Photometry, involving repeated measurements of an object's brightness over time, derives lightcurves that indicate rotation periods and shapes; for instance, irregular lightcurves suggest elongated or tumbling bodies. Spectroscopy analyzes reflected sunlight to classify minor planets into taxonomic types based on absorption features, such as the C-type (carbonaceous) or S-type (silicaceous) spectra that inform composition. Radar observations, using facilities like the Arecibo Observatory (before its 2020 collapse) and NASA's Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, bounce radio waves off nearby minor planets to refine trajectories and model three-dimensional shapes, achieving resolutions down to tens of meters for objects within 0.1 AU. Astrometry provides precise positional data essential for orbital determination. The European Space Agency's Gaia mission, launched in 2013, has revolutionized this by delivering sub-milliarcsecond accuracy (σ ≈ 0.1 mas) for approximately 158,000 minor planets through its wide-field astrometric survey, enabling long-term dynamical studies without ground-based atmospheric distortion.[112] Stellar occultations, where a minor planet temporarily blocks a background star, offer direct size measurements; networks like the International Occultation Timing Association coordinate global observations to yield diameters with uncertainties under 5%, as seen in profiles of Kuiper Belt objects. Despite these advances, challenges persist in ground-based observations. Many minor planets, especially trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs), appear faint with visual magnitudes exceeding 20, requiring large-aperture telescopes and long exposures that strain detector limits. Atmospheric seeing, caused by turbulence, blurs images and limits resolution to about 1 arcsecond, complicating detection of small or distant bodies and necessitating adaptive optics or space-based augmentation for optimal results.Space Missions and In-Situ Studies