Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kirkwood gap

View on Wikipedia

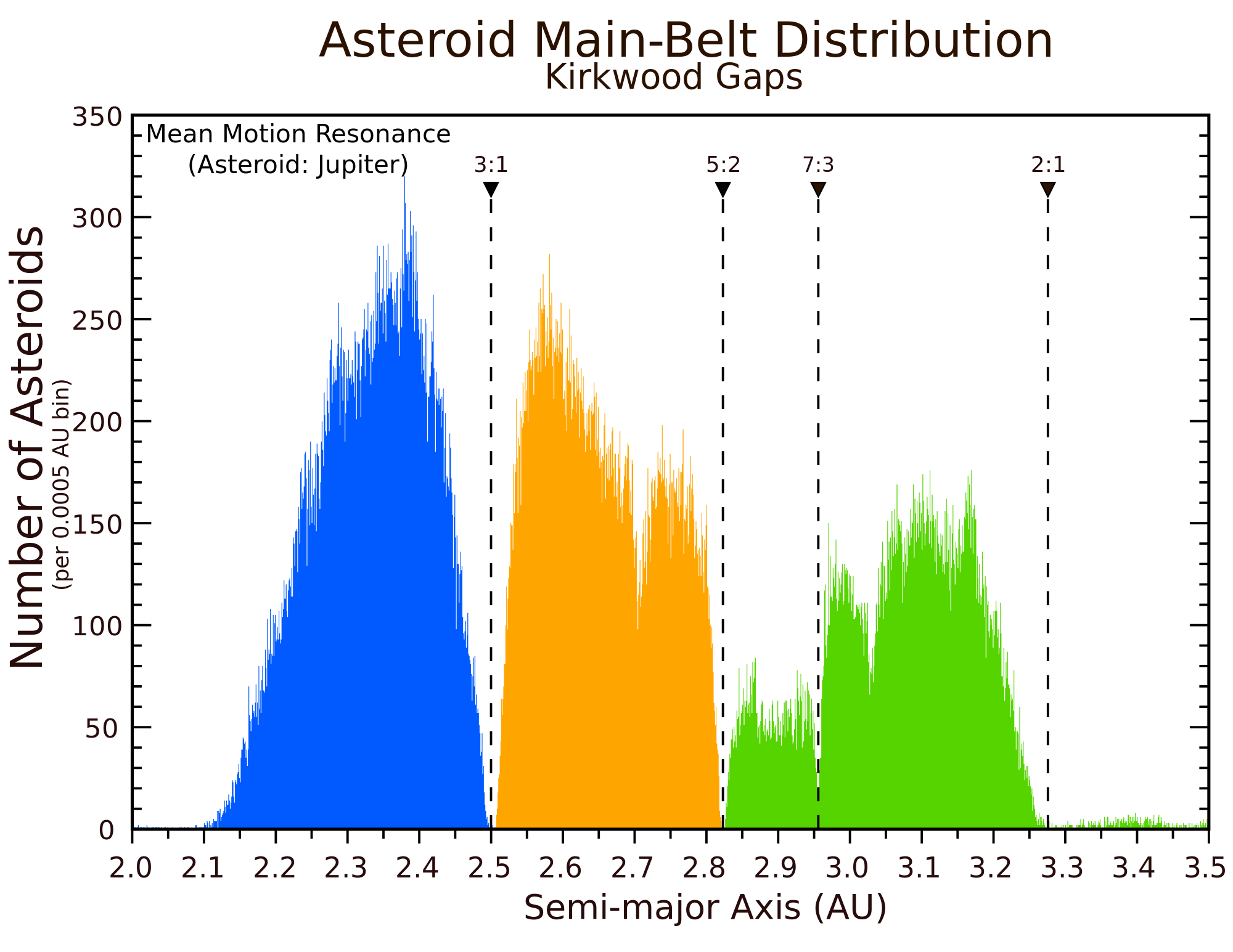

inner main-belt (a < 2.5 AU)

intermediate main-belt (2.5 AU < a < 2.82 AU)

outer main-belt (a > 2.82 AU)

A Kirkwood gap is a gap or dip in the distribution of the semi-major axes (or equivalently of the orbital periods) of the orbits of main-belt asteroids. They correspond to the locations of orbital resonances with Jupiter. The gaps were first noticed in 1866 by Daniel Kirkwood, who also correctly explained their origin in the orbital resonances with Jupiter while a professor at Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania.[1]

For example, there are very few asteroids with semimajor axis near 2.50 AU, period 3.95 years, which would make three orbits for each orbit of Jupiter (hence, called the 3:1 orbital resonance). Other orbital resonances correspond to orbital periods whose lengths are simple fractions of Jupiter's. The weaker resonances lead only to a depletion of asteroids, while spikes in the histogram are often due to the presence of a prominent asteroid family (see List of asteroid families).

Most of the Kirkwood gaps are depleted, unlike the mean-motion resonances (MMR) of Neptune or Jupiter's 3:2 resonance, that retain objects captured during the giant planet migration of the Nice model. The loss of objects from the Kirkwood gaps is due to the overlapping of the ν5 and ν6 secular resonances within the mean-motion resonances. The orbital elements of the asteroids vary chaotically as a result and evolve onto planet-crossing orbits within a few million years.[2] The 2:1 MMR has a few relatively stable islands within the resonance, however. These islands are depleted due to slow diffusion onto less stable orbits. This process, which has been linked to Jupiter and Saturn being near a 5:2 resonance, may have been more rapid when Jupiter's and Saturn's orbits were closer together.[3]

More recently, a relatively small number of asteroids have been found to possess high eccentricity orbits which do lie within the Kirkwood gaps. Examples include the Alinda and Griqua groups. These orbits slowly increase their eccentricity on a timescale of tens of millions of years, and will eventually break out of the resonance due to close encounters with a major planet. This is why asteroids are rarely found in the Kirkwood gaps.

Main gaps

[edit]The most prominent Kirkwood gaps are located at mean orbital radii of:[4]

- 1.780 AU (5:1 resonance)

- 2.065 AU (4:1 resonance)

- 2.502 AU (3:1 resonance), home to the Alinda group of asteroids

- 2.825 AU (5:2 resonance)

- 2.958 AU (7:3 resonance)

- 3.279 AU (2:1 resonance), Hecuba gap, home to the Griqua group of asteroids.

- 3.972 AU (3:2 resonance), home to the Hilda asteroids.

- 4.296 AU (4:3 resonance), home to the Thule group of asteroids.

Weaker and/or narrower gaps are also found at:

- 1.909 AU (9:2 resonance)

- 2.258 AU (7:2 resonance)

- 2.332 AU (10:3 resonance)

- 2.706 AU (8:3 resonance)

- 3.031 AU (9:4 resonance)

- 3.077 AU (11:5 resonance)

- 3.474 AU (11:6 resonance)

- 3.517 AU (9:5 resonance)

- 3.584 AU (7:4 resonance)

- 3.702 AU (5:3 resonance).

Asteroid zones

[edit]The gaps are not seen in a simple snapshot of the locations of the asteroids at any one time because asteroid orbits are elliptical, and many asteroids still cross through the radii corresponding to the gaps. The actual spatial density of asteroids in these gaps does not differ significantly from the neighboring regions.[5]

The main gaps occur at the 3:1, 5:2, 7:3, and 2:1 mean-motion resonances with Jupiter. An asteroid in the 3:1 Kirkwood gap would orbit the Sun three times for each Jovian orbit, for instance. Weaker resonances occur at other semi-major axis values, with fewer asteroids found than nearby. (For example, an 8:3 resonance for asteroids with a semi-major axis of 2.71 AU).[6]

The main or core population of the asteroid belt may be divided into the inner and outer zones, separated by the 3:1 Kirkwood gap at 2.5 AU, and the outer zone may be further divided into middle and outer zones by the 5:2 gap at 2.82 AU:[7]

- 4:1 resonance (2.06 AU)

- Zone I population (inner zone)

- 3:1 resonance (2.5 AU)

- Zone II population (middle zone)

- 5:2 resonance gap (2.82 AU)

- Zone III population (outer zone)

- 2:1 resonance gap (3.28 AU)

4 Vesta is the largest asteroid in the inner zone, 1 Ceres and 2 Pallas in the middle zone, and 10 Hygiea in the outer zone. 87 Sylvia is probably the largest Main Belt asteroid beyond the outer zone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Coleman, Helen Turnbull Waite (1956). Banners in the Wilderness: The Early Years of Washington and Jefferson College. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 158. OCLC 2191890.

- ^ Moons, Michèle; Morbidelli, Alessandro (1995). "Secular resonances inside mean-motion commensurabilities: the 4/1, 3/1, 5/2 and 7/3 cases". Icarus. 114 (1): 33–50. Bibcode:1995Icar..114...33M. doi:10.1006/icar.1995.1041.

- ^ Moons, Michèle; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Migliorini, Fabio (1998). "Dynamical Structure of the 2/1 Commensurability with Jupiter and the Origin of the Resonant Asteroids". Icarus. 135 (2): 458–468. Bibcode:1998Icar..135..458M. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5963.

- ^ Minton, David A.; Malhotra, Renu (2009). "A record of planet migration in the main asteroid belt" (PDF). Nature. 457 (7233): 1109–1111. arXiv:0906.4574. Bibcode:2009Natur.457.1109M. doi:10.1038/nature07778. PMID 19242470. S2CID 2049956. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ McBride, N. & Hughes, D. W. (1990). "The spatial density of asteroids and its variation with asteroidal mass". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 244: 513–520. Bibcode:1990MNRAS.244..513M.

- ^ Ferraz-Mello, S. (June 14–18, 1993). "Kirkwood Gaps and Resonant Groups". proceedings of the 160th International Astronomical Union. Belgirate, Italy: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 175–188. Bibcode:1994IAUS..160..175F.

- ^ Klacka, Jozef (1992). "Mass distribution in the asteroid belt". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 56 (1): 47–52. Bibcode:1992EM&P...56...47K. doi:10.1007/BF00054599. S2CID 123074137.

External links

[edit]- Article on Kirkwood gaps at Wolfram's scienceworld

Kirkwood gap

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Daniel Kirkwood's Discovery

In the mid-19th century, the systematic cataloging of asteroids was underway, but the field remained limited, with only about 87 asteroids having well-determined orbits by 1867.[8] These minor planets, discovered primarily between 1801 and the 1860s, populated the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, prompting astronomers to investigate patterns in their semi-major axes. American astronomer and mathematician Daniel Kirkwood (1814–1895), then a professor at Indiana University, conducted a detailed statistical analysis of this sparse dataset to uncover underlying dynamical structures.[5] Kirkwood presented his findings at the 1866 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, with the paper appearing in the proceedings published in 1867.[9] In this work, he proposed that certain regions in the asteroid belt were depleted due to gravitational interactions with Jupiter, the dominant perturber in the outer solar system. Kirkwood argued that these interactions arose from orbital resonances, where the periodic alignment of an asteroid's orbit with Jupiter's led to cumulative perturbations that ejected asteroids from those zones over time.[8] Specifically, Kirkwood calculated the locations of these expected empty zones by identifying semi-major axes where asteroid orbital periods were simple integer fractions—such as 1/2 or 1/3—of Jupiter's orbital period of 11.86 Earth years.[10] Using Kepler's third law to relate periods to distances from the Sun, he predicted depletions at distances like approximately 2.5 AU for the 3:1 resonance (period 1/3 of Jupiter's) and 3.3 AU for the 2:1 resonance (period 1/2 of Jupiter's), regions that aligned with the observed scarcity in the limited catalog.[5] This theoretical framework marked an early recognition of resonance-driven instability in the solar system, influencing subsequent studies of celestial mechanics.Early Confirmations and Observations

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the rapid increase in asteroid discoveries, facilitated by enhanced observational techniques, provided the empirical data needed to verify Daniel Kirkwood's earlier predictions of orbital depletions. Austrian astronomer Johann Palisa, utilizing visual searches with refracting telescopes at observatories in Vienna and Pola, discovered 122 asteroids between 1874 and 1924, significantly expanding the known population and enabling statistical assessments of their semi-major axis distribution.[11] Similarly, German astronomer Max Wolf pioneered photographic astrometry starting in 1891 at Heidelberg Observatory, identifying over 200 minor planets and further populating catalogs; these efforts confirmed underdensities at resonant locations, such as the 3:1 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter at approximately 2.5 AU, where fewer asteroids were observed than in adjacent zones. In 1918, Japanese astronomer Kiyotsugu Hirayama conducted a detailed analysis of 790 asteroid orbits from the Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch for 1917, examining distributions of mean motions, inclinations, and eccentricities to identify clustering patterns. While noting condensations like the Koronis family (16 asteroids with mean motions around 725" per day), Hirayama highlighted gaps in the mean motion distribution attributable primarily to gravitational resonances with Jupiter, though he also linked some structural features to early asteroid families formed by fragmentation.[12] In a follow-up study published in 1919, Hirayama elaborated on the instability mechanisms, proposing that certain resonant configurations—such as the 2:1—led to abrupt eccentricity growth and dispersal of asteroids, rendering those regions dynamically unstable and explaining the observed depletions beyond mere family dynamics.[13] Early 20th-century orbital catalogs further substantiated these observations through quantitative surveys of asteroid counts binned by semi-major axis. For instance, the Yale University Observatory's compilations in the 1920s, drawing on thousands of determined orbits, revealed pronounced statistical underdensities aligned with Kirkwood gaps; in one analysis of periods near half of Jupiter's (approximately 2166 days, corresponding to the 2:1 resonance at 3.28 AU), zero asteroids appeared in the 2121–2220 day interval, compared to 8 in the preceding 2100–2120 day bin and 5 in the following 2222–2247 day range, underscoring the resonant clearing effects.[14] These catalogs emphasized that such voids persisted across the main belt, with resonant zones showing 50–80% fewer objects than stable intervals, based on representative samples exceeding 1,000 asteroids.[14]Orbital Mechanics

Mean-Motion Resonances with Jupiter

Mean-motion resonances with Jupiter represent a key dynamical process in the asteroid belt, where an asteroid's mean motion (angular speed) is locked in a simple integer ratio to that of Jupiter, denoted as a p:q resonance. In this configuration, the asteroid completes p orbital revolutions around the Sun while Jupiter completes q revolutions, leading to periodic gravitational perturbations that align the bodies at regular intervals.[3] These resonances were first proposed by Daniel Kirkwood in 1866 as the cause of depletions in the asteroid distribution.[15] Jupiter serves as the reference body for these resonances, with its orbit characterized by a semi-major axis of 5.2 AU and a sidereal orbital period of 11.86 Earth years.[16] The semi-major axes of resonant asteroids are calculated using Kepler's third law, which states that the square of the orbital period is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis (). For a p:q resonance, the asteroid's period satisfies , yielding the resonant semi-major axis , where and are Jupiter's semi-major axis and period, respectively. This formula positions the resonances within the asteroid belt's span of approximately 2.0 to 3.3 AU.[17] Resonances are further classified by their order, determined by the difference |p - q|. First-order resonances, where |p - q| = 1 (e.g., the 3:2 resonance), produce stronger perturbations due to the involvement of lower-order terms in the disturbing function.[18] Second-order resonances, with |p - q| = 2 (e.g., the 5:3 resonance), involve higher-order terms and are generally weaker, though still significant in shaping the belt's structure.[19] These resonance locations cluster between 2.0 and 3.3 AU, influencing the overall distribution of asteroids across the inner, middle, and outer regions of the belt.Gravitational Instability Mechanisms

The gravitational instability in Kirkwood gaps arises primarily from the interaction between mean-motion resonances (MMRs) with Jupiter and secular resonances, which collectively destabilize asteroid orbits. In these configurations, asteroids captured in MMRs, such as the 3:1 or 5:2 with Jupiter, experience repeated gravitational perturbations from the planet that align with their orbital precession rates, leading to a process known as eccentricity pumping. This secular forcing amplifies the orbital eccentricity over time, gradually increasing it from low values to levels where the asteroid's perihelion approaches or crosses the orbits of inner planets like Mars. As a result, the orbits become unstable, with asteroids either colliding with planets, being ejected from the solar system, or scattered into the inner solar system, thereby clearing the resonant zones.[20] When multiple resonances overlap within a Kirkwood gap—particularly in the 4:1, 3:1, 5:2, and 7:3 MMRs—this interaction generates extensive chaotic zones characterized by diffusive motion in phase space. The overlapping secular resonances, such as ν5 and ν6, induce rapid variations in both eccentricity and inclination, promoting chaotic diffusion that scatters asteroids unpredictably across orbital elements. This mechanism efficiently removes material from the gaps by driving asteroids into planet-crossing trajectories or direct ejection, with the chaotic behavior extending beyond the nominal resonance widths to explain the observed depletions.[20] Early dynamical models indicate that these instability processes deplete the Kirkwood gaps on timescales of 10 to 100 million years following the formation and dispersal of the primordial asteroid disk, consistent with the age of the solar system. For instance, in the 3:1 gap, chaotic evolution clears most asteroids within a few million years through eccentricity growth and close encounters, while broader gaps like the 2:1 require longer diffusive timescales but follow similar perturbation-driven removal.[21]Gap Locations and Features

Primary Resonances and Gaps

The primary Kirkwood gaps in the asteroid main belt arise from mean-motion resonances with Jupiter, resulting in regions of significantly reduced asteroid density at specific semi-major axes. These gaps are prominently observed in histograms of asteroid distributions, where the depletions are attributed to gravitational perturbations that destabilize orbits over time.[3] The most notable gaps occur at the 3:1, 5:2, 7:3, and 2:1 resonances. The 3:1 resonance is located at approximately 2.50 AU, where asteroids complete three orbits for every one of Jupiter's; this gap hosts the Alinda group of asteroids, which remain in a stable resonant configuration despite the surrounding depletion.[22][23] The 5:2 resonance lies at about 2.82 AU, corresponding to five asteroid orbits per two of Jupiter's.[24] Further outward, the 7:3 resonance at roughly 2.95 AU involves seven asteroid orbits for every three of Jupiter's, creating another clear depletion. The outermost primary gap, at the 2:1 resonance around 3.27 AU (or 3.28 AU in some measurements), represents the largest depletion in the main belt, with asteroid density dropping to less than 1% of adjacent regions and spanning approximately 0.1 to 0.2 AU in width.[24][25][26]| Resonance | Semi-Major Axis (AU) | Notes on Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| 3:1 | 2.50 | Hosts Alinda asteroids; significant but not total depletion |

| 5:2 | 2.82 | Pronounced gap due to resonant instability |

| 7:3 | 2.95 | Clear depletion, with excess clearing outward |

| 2:1 | 3.28 | Largest and deepest gap, <1% density relative to neighbors |