Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

M-type asteroid

View on Wikipedia

M-type (metallic-type, aka M-class) asteroids are a spectral class of asteroids which appear to contain higher concentrations of metal phases (e.g. iron-nickel) than other asteroid classes,[1] and are widely thought to be the source of iron meteorites.[2]

Definition

[edit]Asteroids are classified as M-type based upon their generally featureless and flat to red-sloped absorption spectra in the visible to near-infrared and their moderate optical albedo. Along with the spectrally similar E-type and P-type asteroids (both categories E and P were formerly type-M in older systems), they are included in the larger X-type asteroid group and are distinguishable only by optical albedo:[3]

Characteristics

[edit]Composition

[edit]Although widely assumed to be metal-rich (the reason for use of "M" in the classification), the evidence for a high metal content in the M-type asteroids is only indirect, though highly plausible. Their spectra are similar to those of iron meteorites and enstatite chondrites,[4] and radar observations have shown that their radar albedos are much higher than other asteroid classes,[5] consistent with the presence of higher density compositions like iron-nickel.[1] Nearly all of the M-types have radar albedos at least twice as high as the more common S- and C-type, and roughly one-third have radar albedos ~3× higher.[1]

High resolution spectra of the M-type have sometimes shown subtle features longward of 0.75 μm and shortward of 0.55 μm.[6] The presence of silicates is evident in many,[7][8] and a significant fraction show evidence of absorption features at 3 μm, attributed to hydrated silicates.[9] The presence of silicates, and especially hydrated silicates, is at odds with the traditional interpretation of M-types as remnant iron cores.

Bulk density and porosity

[edit]The bulk density of an asteroid provides clues about its composition and meteoritic analogs.[10] For the M-types, the proposed analogs have bulk densities that range from ~3 g/cm3 for some types of carbonaceous chondrites up to nearly 8 g/cm3 for the iron-nickel present in iron-meteorites.[2][4][9] Given the bulk density of an asteroid and the density of the materials that make it up (aka particle or grain density), one can calculate its porosity and infer something of its internal structure; for example, whether an object is coherent, a rubble pile, or something in-between.[10]

To calculate the bulk density of an asteroid requires an accurate estimate of its mass and volume; both of these are difficult to obtain given their small size relative to other Solar System objects. In the case of the larger asteroids, one can estimate mass by observing how their gravitational field affects other objects, including other asteroids and orbiting or flyby spacecraft.[11] If an asteroid possesses one or more moons, one can use their collective orbital parameters (e.g. orbital period, semimajor axis) to estimate the masses of the ensemble, for example in the two-body problem.

To estimate an asteroid's volume requires, at a minimum, an estimate of an asteroid's diameter. In most cases, these are estimated from the visual albedo (brightness) of the asteroid, chord-lengths during occultations, or their thermal emissions (e.g. IRAS mission). In a few cases, astronomers have managed to develop three-dimensional shape models using a variety of techniques (cf. 16 Psyche or 216 Kleopatra for examples) or, in a few lucky instances, from spacecraft imaging (cf. 162173 Ryugu).

| Asteroid | Density | Radar Albedo | Method (mass, size) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 Psyche | 3.8 ± 0.3[12] | 0.34 ± 0.08[13] | Ephemeris, shape model |

| 21 Lutetia | 3.4 ± 0.3[14] | 0.24 ± 0.07[1] | Rosetta spacecraft flyby, direct imaging |

| 22 Kalliope | 4.1 ± 0.5[15][16] | 0.15 ± 0.05[5] | Orbit of its moon Linus, shape model |

| 69 Hesperia | 4.4 ± 1.0[17] | 0.45 ± 0.12[1] | Ephemeris, thermal IR/radar size estimate |

| 92 Undina | 4.4 ± 0.4[17] | 0.38 ± 0.09[1] | Ephemeris, thermal IR/radar size estimate |

| 129 Antigone | 3.0 ± 1.0[17] | 0.36 ± 0.09[1] | Ephemeris, thermal IR/radar size estimate |

| 216 Kleopatra | 3.4 ± 0.5[18] | 0.43 ± 0.10[19] | Orbits of its two moons, shape model |

Of these, mass measurements made via spacecraft deflection or the orbits of moons are considered the most reliable. Ephemeris estimates are based on the subtle gravitational pull of other objects on that asteroid, or vice versa, and are considered less reliable. The exception to this caveat may be Psyche, as it is the most massive M-type asteroid and has numerous mass estimates.[12] Size estimates based on shape models (usually derived from adaptive optics, occultations, and radar imaging) are the most reliable. Direct spacecraft imaging (Lutetia) is also quite reliable. Sizes based on indirect methods like thermal IR (e.g. IRAS) and radar echoes are less reliable.

None of the M-type asteroids have bulk densities consistent with a pure iron-nickel core. If these objects are porous (aka rubble-piles), then that interpretation may still hold; this is unlikely for Psyche,[12] because of its large size. Given the spectral evidence of silicates on most M-type asteroids, the consensus interpretation for most of these larger asteroids is that they are composed of lower density meteorite analogs (e.g. enstatite chondrites, metal-rich carbonaceous chondrites, mesosiderites), and in some cases may also be rubble piles.[20][18][12]

Formation

[edit]The earliest interpretation of the M-type asteroids was that they were the remnant cores of early protoplanets, stripped of their overlying crust and mantles by massive collisions that are thought to have been frequent in the early history of the Solar System.[2]

It is acknowledged that some of the smaller M-type asteroids (<100 km) may have formed in this way, but that interpretation was challenged for 16 Psyche, the largest of the M-type asteroids.[21] There are three arguments against Psyche forming in this way.[21] First, it must have started as a Vesta-sized (~500 km) protoplanet; statistically, it is unlikely that Psyche was completely disrupted while Vesta remained intact. Second, there is little or no observational evidence for an asteroid family associated with Psyche, and third, there is no spectroscopic evidence for the expected mantle fragments (i.e. olivine) that would have resulted from this event. Instead, it has been argued that Psyche is the remnant of a protoplanet that was shattered and gravitationally re-accumulated into a well-mixed iron-silicate object.[21] There are numerous examples of metal-silicate meteorites, aka mesosiderites, that might be objects from such a parent body.

One possible response to this second interpretation is that the M-type asteroids (including 16 Psyche) accumulated much closer to the Sun (1–2 au), were stripped of their thin crust/mantles while still molten (or partially so), and later dynamically moved into the current asteroid belt.[22]

A third view is that the largest M-types, including 16 Psyche, may be differentiated bodies (like 1 Ceres and 4 Vesta) but, given the right mix of iron and volatiles (e.g. sulfur), these bodies may have experienced a type of iron volcanism, a.k.a. ferrovolcanism, while still cooling.[23]

Notable examples

[edit]In the JPL Small Body Database, there are 980 asteroids classified under the Tholen asteroid spectral classification system.[24] Of those, 38 are classified as M-type.[25] Another 10 were originally classified as X-type, but are now counted among the M-types because their optical albedos fall between 0.1 and 0.3.[26] Overall, the M-types make up approximately 5% of the asteroids classified under the Tholen taxonomy.

(16) Psyche

[edit]16 Psyche is the largest M-type asteroid with a mean diameter of 222 km, and has a relatively high mean radar albedo of suggesting it has a high metal content in the upper few meters of its surface.[13] The Psyche spacecraft, launched on October 13, 2023, is en route to visit 16 Psyche, arriving in 2029.

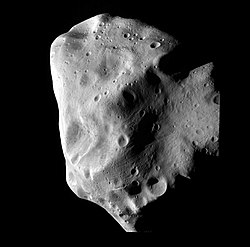

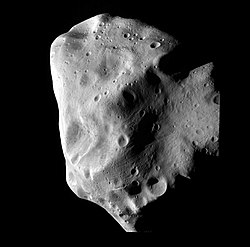

(21) Lutetia

[edit]21 Lutetia has a mean diameter of 100 km,[1] and was the first M-type asteroid to have been imaged by a spacecraft when the Rosetta space probe visited it on 10 July 2010.[27] Its mean radar albedo of is roughly twice that of the average S-type or C-type asteroid, and suggests its regolith contains an elevated amount of metal phases relative to other asteroid classes.[1] Analysis using data from the Rosetta spectrometer (VIRTIS) was consistent with estatitic or iron-rich carbonaceous chondritic materials.[28]

(22) Kalliope

[edit]22 Kalliope is the second largest M-type asteroid with a mean diameter of 150 km.[15] A single moon, named Linus, was discovered in 2001[29] and allows for an accurate mass estimate. Unlike most of the M-type asteroids, Kalliope's radar albedo is 0.15, similar to the S- and C-type asteroids,[5] and does not suggest an enrichment of metal in its regolith. It has been the target of high resolution adaptive optics imaging which has been used to provide a reliable size and shape, and a relatively high bulk density of 4.1 g/cm3.[15][16]

(216) Kleopatra

[edit]216 Kleopatra, with a mean diameter of 122 km, is the third largest M-type asteroid known after 16 Psyche and 22 Kalliope.[19] Radar delay-Doppler imaging, high-resolution telescopic images, and several stellar occultations show it to be a contact binary asteroid with a shape commonly referred to as a "dog-bone" or "dumbbell."[19] Radar observations from the Arecibo radar telescope indicate a very high radar albedo of in the southern hemisphere, consistent with a metal-rich composition.[19] Kleopatra is also notable for the presence of two small moons, named Alexhelios and Cleoselena, which have allowed its mass and bulk density to be accurately computed.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shepard, M.K.; et al. (2015). "A radar survey of M- and X-class asteroids: III. Insights into their composition, hydration state, and structure". Icarus. 245: 38–55. Bibcode:2015Icar..245...38S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.09.016.

- ^ a b c Bell, J.F.; et al. (2015). "Asteroids: The big picture". In Binzel, Richard P.; Gehrels, Tom; Matthews, Mildred Shapley (eds.). Asteroids II. University of Arizona Press. pp. 921–948. ISBN 978-0-8165-2281-1.

- ^ Tholen, D.J.; Barucci, M.A. (1989). "Asteroid taxonomy". In Binzel, Richard P.; Gehrels, Tom; Matthews, Mildred Shapley (eds.). Asteroids II. University of Arizona Press. pp. 298–315. ISBN 0-8165-1123-3.

- ^ a b Gaffey; Bell, J.F.; Cruikshank, D. (1989). "Asteroid surface mineralogy". In Binzel, Richard P.; Gehrels, Tom; Matthews, Mildred Shapley (eds.). Asteroids II. University of Arizona Press. pp. 98–127. ISBN 0-8165-1123-3.

- ^ a b c Magri, C.; et al. (2007). "A radar survey of main-belt asteroids: Arecibo observations of 55 objects during 1999–2004". Icarus. 186 (1): 126–151. Bibcode:2007Icar..186..126M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.018.

- ^ Bus, S.J.; Binzel, R.P. (2002). "Phase II of the Small Main-belt Asteroid Spectroscopy Survey: A feature-based taxonomy". Icarus. 158 (1): 146–177. Bibcode:2002Icar..158..146B. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6856. S2CID 4880578.

- ^ Ockert-Bell, M.; et al. (2010). "The composition of M-type asteroids: Synthesis of spectroscopic and radar observations". Icarus. 210 (2): 674–692. Bibcode:2010Icar..210..674O. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.08.002.

- ^ Lupishko, D.F.; et al. (1982). "UBV photometry of the M-type asteroids 16 Psyche and 22 Kalliope". Solar System Research. 16: 75. Bibcode:1982AVest..16..101L.

- ^ a b Rivkin, A.S.; et al. (2000). "The nature of M-class asteroids from 3-micron observations". Icarus. 145 (2): 351. Bibcode:2000Icar..145..351R. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6354.

- ^ a b Britt, D.T.; et al. (2015). "Asteroids' density, porosity, and structure". In Bottke, W.F.; Cellino, A.; Paolicchi, P.; Binzel, R.P. (eds.). Asteroids III. University of Arizona Press. pp. 485–500. ISBN 978-0-8165-1123-5.

- ^ Pitjeva, E.V.; Pitjev, N.P. (2018). "Masses of the main asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt from the motions of planets and spacecraft". Earth and Planetary Astrophysics. 44 (8–9): 554–566. arXiv:1811.05191v1. Bibcode:2018AstL...44..554P. doi:10.1134/S1063773718090050. S2CID 255197841.

- ^ a b c d Elkins-Tanton, L. T.; et al. (2020). "Observations, meteorites, and models: A preflight assessment of the composition and formation of (16) Psyche". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 125 (3): 23. Bibcode:2020JGRE..12506296E. doi:10.1029/2019JE006296. PMC 7375145. PMID 32714727. S2CID 214018872.

- ^ a b Shepard, M.K.; et al. (2021). "Asteroid 16 Psyche: Shape, features, and global map". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (4): 16. arXiv:2110.03635. Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2..125S. doi:10.3847/PSJ/abfdba. S2CID 235918955.

- ^ Sierks, H.; et al. (2011). "Images of asteroid 21 Lutetia: A remnant planetesimal from the early Solar system" (PDF). Science. 334 (6055): 487–490. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..487S. doi:10.1126/science.1207325. hdl:1721.1/110553. PMID 22034428. S2CID 17580478.

- ^ a b c Vernazza, P.; et al. (2021). "VLT/SPHERE imaging survey of the largest main-belt asteroids: Final results and synthesis". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 654 (A56): 48. Bibcode:2021A&A...654A..56V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202141781. hdl:10261/263281. S2CID 239104699.

- ^ a b Ferrais, M. (2021). M-type (22) Kalliope: High density and differentiated interior. 15th Europlanet Science Congress. Bibcode:2021EPSC...15..696F. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via NASA ADS.

- ^ a b c Carry, B. (2012). "Density of asteroids". Planetary and Space Science. 73 (1): 98–118. arXiv:1203.4336. Bibcode:2012P&SS...73...98C. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2012.03.009. S2CID 119226456.

- ^ a b Marchis, F.; Jorda, L.; Vernazza, P.; Brož, M.; Hanuš, J.; Ferrais, M.; et al. (September 2021). "(216) Kleopatra, a low density, critically rotating, M-type asteroid". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 653: A57. arXiv:2108.07207. Bibcode:2021A&A...653A..57M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202140874. S2CID 237091036. A57. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Shepard, Michael K.; Timerson, Bradley; Scheeres, Daniel J.; Benner, Lance A.M.; Giorgini, Jon D.; Howell, Ellen S.; et al. (2018). "A revised shape model of asteroid (216) Kleopatra". Icarus. 311: 197–209. Bibcode:2018Icar..311..197S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.04.002.

- ^ Descamps, P.; Marchis, F.; Pollock, J.; Berthier, J.; Vachier, F.; Birlan, M.; et al. (2008). "New determination of the size and bulk density of the binary asteroid 22 Kalliope from observations of mutual eclipses". Icarus. 196 (2): 578–600. arXiv:0710.1471. Bibcode:2008Icar..196..578D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.03.014. S2CID 118437111.

- ^ a b c Davis, D.R.; Farinella, P.; Marzari, F. (1999). "The missing Psyche family: Collisionally eroded or never formed?". Icarus. 137 (1): 140–151. Bibcode:1999Icar..137..140D. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.6037.

- ^ Scott, E.; et al. (2014). "Origin of igneous meteorites and differentiated asteroids". Asteroids. ACM: 483. Bibcode:2014acm..conf..483S.

- ^ Johnson, B.C.; Sori, M.M.; Evans, A.J. (2020). "Ferrovolcanism of metal worlds and the origin of pallasites". Nature Astronomy. 4: 41–44. arXiv:1909.07451. Bibcode:2020NatAs...4...41J. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0885-x. S2CID 202583406.

- ^ "spec. type (Tholen) is defined". JPL Solar System Dynamics. JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine. JPL. Retrieved 26 Dec 2021.

- ^ "spec. type (Tholen) = M". JPL Solar System Dynamics. JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine. JPL. Retrieved 26 Dec 2021.

- ^ "spec. type (Tholen) = X AND albedo >= 0.1 AND albedo <= 0.3". JPL Solar System Dynamics. JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine. JPL. Retrieved 26 Dec 2021.

- ^ Schulz, R.; et al. (2012). "Rosetta fly-by at asteroid (21) Lutetia: An overview". Planetary and Space Science. 66 (1): 2–8. Bibcode:2012P&SS...66....2S. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2011.11.013.

- ^ Coradini, A.; et al. (2011). "The surface composition and temperature of asteroid 21 Lutetia as observed by Rosetta/VIRTIS". Science. 334 (492): 492–494. Bibcode:2011Sci...334..492C. doi:10.1126/science.1204062. PMID 22034430. S2CID 19439721.

- ^ Margot, J.L.; Brown, M.E. (2003). "A low-density M-type asteroid in the main belt". Science. 300 (5627): 1939–1942. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1939M. doi:10.1126/science.1085844. PMID 12817147. S2CID 5479442.

- ^ Descamps, P.; et al. (2011). "Triplicity and physical characteristics of asteroid (216) Kleopatra". Icarus. 245 (2): 64–69. arXiv:1011.5263. Bibcode:2011Icar..211.1022D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.11.016. S2CID 119286272.

M-type asteroid

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Spectral Characteristics

M-type asteroids are characterized by relatively flat and featureless reflectance spectra in the visible and near-infrared wavelengths, typically spanning 0.4 to 0.9 μm, with no prominent absorption features.[10] These spectra exhibit a slight reddening with wavelength, but lack the distinct silicate absorption bands near 1 μm and 2 μm that are hallmarks of S-type asteroids.[11] Their moderate albedo, ranging from 0.10 to 0.30, further distinguishes them from the lower-albedo C-types (typically <0.05) and the redder, more sloped spectra of S-types, which show stronger curvature due to olivine and pyroxene minerals.[2] This combination of spectral flatness and albedo supports their classification as metallic or metal-rich bodies.[10] In comparison, C-type asteroids display neutral to slightly blue-sloped spectra in the visible range, often with a subtle drop-off in the ultraviolet, and lack the moderate reddening seen in M-types.[10] S-types, by contrast, have moderately red slopes and clear absorption features at 0.9–1.0 μm and around 2 μm attributable to silicates, setting them apart from the essentially featureless M-type profiles.[11] These differences in spectral slope and the absence of silicate bands in M-types were key to their initial separation in early taxonomic schemes.[10] A critical refinement in distinguishing pure M-types from related subtypes, such as Xk, involves observations at longer wavelengths, particularly the presence or absence of a 3-μm absorption feature indicative of hydration (OH or H₂O).[12] Pure M-types lack this feature, consistent with an anhydrous metallic composition, whereas Xk subtypes exhibit a redder spectral slope in the near-infrared combined with the 3-μm band, suggesting hydrated silicates or other volatiles.[11] This hydration signature, detected in over 35% of surveyed M-class objects, led to subdivisions like the W-class for hydrated variants.[12] The spectral traits defining M-types were formalized through cluster analysis of photometric and spectroscopic data in Tholen's 1984 taxonomy, which grouped them within the X-complex based on their featureless, moderately red spectra and albedo.[10] This framework was extended by Bus (1999) and Bus and Binzel (2002), who refined the classification using principal component analysis of visible spectra, emphasizing the flat-to-moderately red slopes and absence of diagnostic bands to delineate M from other X-subgroups like Xk.[11] These systems established the observational criteria still used today for identifying M-types.[11]Taxonomic Identification

M-type asteroids are classified within several major taxonomic systems based on their reflectance spectra and albedo properties. The Tholen taxonomy, established in 1984, defines the M-class as asteroids exhibiting featureless, moderately red-sloped spectra in the visible to near-infrared range and moderate visual albedos typically between 0.10 and 0.30. This system groups them separately from other X-complex types due to their intermediate albedo levels. The SMASS II taxonomy, developed by Bus and Binzel in 2002, refines visible-wavelength classifications and aligns M-types with similar featureless spectra but emphasizes principal component analysis to distinguish subtle slope variations, often mapping them to the X group with albedo as a secondary discriminator. The Bus-DeMeo taxonomy, introduced in 2009, extends coverage to 0.45–2.45 μm and categorizes pure M-types within the X-complex as those with moderate near-infrared slopes and no prominent absorption features, contrasting with reddish Xk subtypes or low-albedo Xc types; it reclassifies many Tholen M-types as X or Xk based on extended spectral data. Assignment to the M-type category requires specific criteria to exclude mimics from C- or S-like classes. Key indicators include a high radar albedo exceeding 0.2, indicative of metallic content, alongside the absence of a ultraviolet drop-off below 0.55 μm that characterizes carbonaceous asteroids.[4] Additionally, spectra must lack diagnostic features such as the 1 μm olivine-pyroxene band seen in S-types or the broad 3 μm hydration band in some X subtypes. Spectral flatness in the visible region serves as a supporting trait for identification. In the main asteroid belt, M-types comprise approximately 5–7% of the population, with a bias-corrected distribution derived from spectroscopic surveys showing higher concentrations in the middle belt at semi-major axes of 2.5–3.0 AU, where they peak around 2.7 AU. This zoning reflects dynamical and compositional gradients from the belt's formation. Post-2010 refinements to M-type identification leverage thermal infrared data from the NEOWISE mission, which provides diameters and albedos for over 100,000 main-belt asteroids via near-Earth asteroid thermal modeling. These measurements distinguish true M-types (moderate albedos ~0.1–0.4) from low-albedo P-types and high-albedo E-types within the X-complex, enhancing purity in classifications previously limited by optical data alone.[13]Physical Properties

Composition

M-type asteroids are inferred to have surfaces dominated by metallic iron-nickel (Fe-Ni) alloys with high metal content analogous to iron meteorites (primarily Fe-Ni alloys with 5–10% nickel), but observations indicate mixtures with silicate inclusions typically at 10–50% or more, based on spectroscopic and radar data linking M-types to the exposed cores of differentiated planetesimals.[14][15][16] Some M-type asteroids show evidence of minor silicate components, such as enstatite and olivine, indicating heterogeneous surfaces possibly from incomplete differentiation or mixing with crustal material.[9] These silicates are often chondritic in nature, as seen in analogs like the Landes meteorite, which contains 16% silicates including pyroxene and olivine alongside 81% NiFe metal.[9] Trace minerals including troilite (FeS) and nickel-iron phosphides like schreibersite are present at low abundances (0.1–1% for sulfur and phosphorus), mirroring components in IAB-group iron meteorites that are considered potential parent materials for M-types.[14] For instance, the Mundrabilla meteorite, an IAB iron with silicate inclusions, features up to 35% troilite by volume and minor enstatite-olivine silicates embedded in its Fe-Ni matrix (7.8% Ni).[17][18] Compositional variations exist among M-types, ranging from high metallic Fe-Ni surfaces akin to unweathered iron meteorites to rubble-like structures incorporating embedded silicates and sulfides, as evidenced by meteorite studies including those of IAB irons like Mundrabilla.[19] Recent 2025 analyses of (16) Psyche suggest a substantial non-metallic component, possibly due to ferrovolcanism or incomplete differentiation, implying less than 50% metal if assuming low porosity.[16] These differences suggest diverse exposure histories or regolith processes on their surfaces.[9]Density and Porosity

M-type asteroids exhibit bulk densities typically ranging from 3.0 to 5.5 g/cm³, significantly higher than those of stony asteroids, which average 2–3 g/cm³.[20] This elevated density range reflects their metal-rich interiors, primarily composed of iron-nickel alloys mixed with silicates, and distinguishes them from more porous carbonaceous or silicate-dominated bodies.[20] For instance, spacecraft measurements of (21) Lutetia yielded a bulk density of approximately 3.4 ± 0.3 g/cm³, while recent analyses of (16) Psyche estimate 3.88 ± 0.33 g/cm³ (as of 2025).[21][16] These densities are derived by combining asteroid diameters obtained from infrared thermal emission data, such as surveys by NEOWISE, with mass estimates from gravitational perturbations on nearby objects or orbital dynamics in binary systems. For binary M-types like (22) Kalliope, the satellite's orbit provides precise mass constraints, leading to densities around 4.4 ± 0.46 g/cm³ (as of 2022) when paired with shape models from adaptive optics imaging.[20][22] Such methods reveal a consistent pattern of compactness, with variations attributed to compositional differences or internal structures rather than measurement errors.[20] Porosity estimates for M-type asteroids generally range from 0% to 50%, with recent models indicating low to moderate values for metallic-rich bodies but higher if assuming pure metal for low-density examples like Psyche.[23][16] These values are inferred from bulk density comparisons to grain densities of metallic meteorites (around 7–8 g/cm³) and detailed shape modeling combined with rotation period analyses.[23] Variations in porosity suggest efficient packing of metal phases in some, consistent with formation processes that minimize fracturing, unlike the higher porosities (up to 50%) seen in primitive asteroids.[20] The high densities of M-type asteroids imply greater internal strength, enabling faster rotation rates than those sustainable by weaker stony bodies. Small M-types, in particular, often approach rotation periods below 2 hours without disruption, as their metallic cohesion resists centrifugal forces that would dismantle rubble-pile structures at similar spins. This correlation underscores the role of density in governing dynamical stability and evolutionary pathways.Origin and Formation

Planetesimal Differentiation

Planetesimal differentiation in the early solar system was primarily driven by radiogenic heating from the short-lived isotope ^{26}Al, which decayed with a half-life of approximately 0.73 million years and provided sufficient energy to melt small protoplanetary bodies within the first few million years after solar system formation around 4.567 billion years ago.[24] This heating caused planetesimals, typically tens to hundreds of kilometers in diameter, to partially or fully melt, enabling gravitational segregation where denser metallic iron-nickel alloys sank to form central cores, while lighter silicate materials rose to form mantles and crusts.[25] The process occurred rapidly, with core formation models indicating metal-silicate separation within 1-2 million years for bodies accreting early in the inner solar system, aligning with the peak abundance of ^{26}Al.[26] M-type asteroids are interpreted as remnants of these metallic cores exposed after the loss of overlying silicate layers, with observed diameters ranging from 1 to about 200 km, such as the largest example (16) Psyche at roughly 226 km.[27] This size distribution is consistent with fragments derived from progenitor planetesimals originally 100-500 km in diameter, which underwent differentiation before partial disruption, as inferred from dynamical models of early asteroid belt evolution and the volumes required to produce observed iron meteorite groups.[28] The metallic composition of these cores, dominated by iron and nickel, serves as a hallmark of successful differentiation in these bodies.[29] Supporting evidence comes from iron meteorites, which are widely regarded as analogs for M-type asteroid material, exhibiting compositions and microstructures indicative of slow cooling in metallic cores of differentiated planetesimals.[14] Crystallization ages of these meteorites, determined via methods like the Re-Os chronometer, cluster around 4.5-4.6 billion years ago, matching the timeline of asteroid belt formation and the era of ^{26}Al-driven heating.[30] In the inner solar system, 16O-poor reservoirs—relative to calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions— This isotopic dichotomy, observed in non-carbonaceous meteorites linked to inner planetesimals, suggests heterogeneous protoplanetary disk environments that promoted differentiation in metal-rich precursors to M-types.[31][32]Collisional Processes

Asteroids in the middle main belt, including M-types, are subject to collisional interactions influenced by the Yarkovsky and YORP effects, which drive orbital migration and spin changes that alter their dynamical pathways. The Yarkovsky effect induces a semimajor axis drift in asteroids smaller than approximately 30-40 km, while the YORP effect modifies spin rates and obliquities, leading to increased dispersion in proper elements and higher encounter probabilities within dense regions of the belt.[33] These non-gravitational forces contribute to the evolution of asteroid families and elevate collision rates by facilitating overlaps in orbital zones, particularly for metallic bodies that may have originated from differentiated planetesimals.[34] Catastrophic collisions in the early solar system played a key role in exposing the metallic cores of M-type asteroids by stripping away overlying silicate mantles from differentiated parent bodies. Dynamical models of the asteroid belt's collisional evolution indicate that such events were prevalent during the early intense bombardment phase within the first few hundred million years after solar system formation, with impacts disrupting larger planetesimals and leaving behind exposed metal cores as remnants.[35] These models simulate the belt's history over 4.5 Gyr, showing that mantle-stripping collisions produced numerous metallic survivors, consistent with the observed population of M-types like (16) Psyche, which represent fragments of once-larger differentiated protoplanets.[36] Micrometeorite impacts contribute to regolith formation on M-type asteroid surfaces, gradually building a layer of fragmented material while inducing space weathering that subtly alters their spectral properties. Over time, these impacts create melt and vapor deposits, leading to a slight reddening of spectra as metallic grains are modified, though the effect is less pronounced than on silicate-rich bodies due to the absence of hydration features.[37] This process, driven by continuous bombardment in the asteroid belt, results in a regolith characterized by low porosity and metallic cohesion, influencing the overall reflectance and radar properties of these objects.[38] Simulations of long-term collisional evolution reveal low survival rates for intact metallic cores in the asteroid belt, with less than 1% of the original differentiated cores persisting due to ongoing disruptions over billions of years. These models account for both early bombardment and steady-state collisions, demonstrating that while initial core exposure was widespread, subsequent impacts have fragmented most remnants, leaving only a sparse population of M-types today.[35] The rarity underscores the violent history of the belt, where dynamical depletion mechanisms further reduce the number of survivors.[36]Observational Methods

Ground-Based Techniques

Ground-based techniques for studying M-type asteroids primarily rely on remote sensing from Earth-based observatories, enabling the derivation of key physical properties such as albedo, spectral slopes, shape, and surface characteristics without direct spacecraft encounters. Visible and near-infrared (near-IR) spectroscopy, conducted using large telescopes, has been instrumental in characterizing the reflectance properties of these asteroids. Observations from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) with the SpeX spectrograph, for instance, have revealed moderate albedos around 0.10–0.20 for M-type asteroids, along with generally featureless spectra but subtle variations in spectral slopes that indicate compositional diversity within the class.[39] Similarly, spectroscopic surveys using facilities like the IRTF have measured positive spectral slopes in the 0.4–2.5 μm range for multiple M-types, helping to refine albedo estimates and distinguish metallic signatures from potential silicate admixtures. These data contribute to taxonomic placement by confirming the lack of strong absorption features typical of M-types, though some objects show weak bands suggestive of hydration or other minerals.[40] Radar observations, pioneered in the 1980s with facilities such as Arecibo and Goldstone, provide high-resolution imaging of asteroid shapes and surfaces, offering direct evidence for metallic compositions in M-types. Early Arecibo radar detections of objects like (16) Psyche and (21) Lutetia during 1980–1995 yielded high radar albedos exceeding 0.3, consistent with metal-rich surfaces and bulk densities around 3–8 g/cm³.[41] Subsequent surveys, including those from 1999–2003, expanded this to over 50 M- and X-class asteroids, confirming that about one-third exhibit radar albedos indicative of exposed metal, with detailed delay-Doppler images revealing irregular shapes and potential binary systems.[42] These observations, often combining Arecibo's S-band and Goldstone's transmissions, have been crucial since the 1980s for validating the metallic interpretation of M-types through echo strengths far higher than those of carbonaceous bodies.[43] Polarimetry, which measures the polarization of sunlight scattered by asteroid surfaces, offers insights into regolith properties like grain size and roughness for M-types. Broadband polarimetric observations in the visible range have shown that M-type asteroids exhibit a wide range of negative polarization branches, with inversion angles typically 20–30° and maximum polarization degrees around 1–2%, suggesting coarser grains (tens of micrometers) and moderate surface roughness compared to other classes.[44] More recent studies correlate these polarimetric parameters with radar data, revealing that M-types with deeper negative polarization often have higher circular polarization ratios, implying metallic regolith with low porosity and larger particle sizes that enhance backscattering.[2] This technique has highlighted diversity, such as the unusually large inversion angle for (21) Lutetia, pointing to a rougher or more complex surface texture.[45] Thermal modeling using infrared data from surveys like NEOWISE has provided robust estimates of M-type diameters and surface properties since the 2010s. The Near-Earth Asteroid Thermal Model (NEATM), fitted to NEOWISE mid-infrared photometry, derives diameters for hundreds of M-types, such as 226 km for (16) Psyche, with beaming parameters η around 0.8–1.2 indicating low thermal inertia consistent with metallic surfaces.[46] These models account for thermal emission and reflected sunlight, yielding albedos that align with radar constraints and confirming sizes for over 6,000 main-belt asteroids, including M-types, with uncertainties typically under 10–20%.[47] By the third year of the NEOWISE reactivation mission (2015–2016), such analyses refined beaming parameters to probe regolith thermal behavior, distinguishing M-types' efficient heat conduction from more insulating primitives.[46]Spacecraft Missions

The European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft conducted a flyby of the M-type asteroid (21) Lutetia on July 10, 2010, providing the first close-up observations of such an object. Instruments aboard Rosetta, including the OSIRIS camera and RPC plasma sensors, revealed a surface rich in silicates and primitive materials alongside metallic components, confirming Lutetia's classification while indicating it is not a pure metallic body but rather a differentiated planetesimal with a complex history. The mission measured Lutetia's bulk density at 3.4 g/cm³, suggesting modest porosity and enrichment in heavy metals like iron and nickel, which supports models of early solar system core-mantle differentiation. These findings refined understandings of M-type compositions, showing they often include non-metallic regolith overlying metallic substrates. NASA's Psyche mission, launched on October 13, 2023, is dedicated to exploring the M-type asteroid (16) Psyche, believed to be the exposed core of a protoplanet. The spacecraft employs solar-electric propulsion for its trajectory, including a Mars gravity assist in May 2026 to reach the asteroid by August 2029. Key instruments include the Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer (GRNS), which will map elemental abundances such as iron, nickel, silicon, and sulfur through detection of cosmic-ray-induced gamma rays and neutrons, providing in-situ data on Psyche's metallic content and differentiation history. As of November 2025, Psyche remains in its cruise phase, having successfully captured images of Earth and the Moon in July 2025 during routine systems checks, with all instruments functioning nominally en route to the Mars flyby.[48] Recent private sector efforts include AstroForge's Odin mission, launched on February 26, 2025, targeting the suspected M-type near-Earth asteroid 2022 OB5 for imaging to assess its metallic potential; however, contact was lost shortly after deployment, limiting scientific returns.[49] Ongoing NASA missions like Lucy, primarily focused on Jupiter Trojans, may indirectly observe metallic objects through extended operations, while follow-up concepts to the DART impact on the S-type binary Didymos-Dimorphos could inspire kinetic deflection tests on metallic targets in planetary defense scenarios.Notable Examples

(16) Psyche

(16) Psyche is the largest and most massive known M-type asteroid, serving as the namesake for its spectral class due to its prominent metallic characteristics. Discovered on March 17, 1852, by Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis at the Capodimonte Observatory in Naples, it was the 16th asteroid identified and named after the Greek goddess of the soul.[7] Its spectrum exhibits the shallow absorption features and reddish slope typical of M-type asteroids, consistent with a high iron-nickel content.[50] With a mean diameter of approximately 226 km, Psyche accounts for about 1% of the total mass in the asteroid belt.[7] Radar observations from the Arecibo Observatory have revealed an irregular, potato-like shape with dimensions roughly 279 km × 232 km × 181 km, indicating a triaxial ellipsoid form with prominent equatorial depressions.[51] The asteroid rotates rapidly with a sidereal period of 4.196 hours, and its high radar albedo of about 0.37 suggests a surface rich in metallic material, potentially with low macroporosity in the regolith.[52] Its optical albedo is estimated at 0.26, higher than typical carbonaceous asteroids but indicative of exposed metal.[53] Pre-mission estimates place Psyche's bulk density at around 3.9 g/cm³, significantly lower than that of pure iron-nickel metal (about 7.8 g/cm³), implying either 30–60% porosity or a mixture of metal with silicate components.[54] This density value derives from combining radar-derived shape models with gravitational perturbations observed on nearby asteroids. Early suggestions of a binary system, based on lightcurve irregularities, have been ruled out by high-resolution radar imaging and occultation data, confirming Psyche as a single body.[51] Historical ground-based observations since its discovery have included multiple stellar occultations, such as those in 1992, 2004, and 2014, which provided chords revealing surface topography including craters and ridges up to several kilometers in relief.[52] These events, analyzed by the International Occultation Timing Association, helped refine the asteroid's irregular silhouette and constrain its orientation. NASA's Psyche mission, launched on October 13, 2023, aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, is en route for arrival in August 2029 to orbit the asteroid for 21 months. As of November 2025, the mission has overcome a propulsion anomaly earlier in the year and successfully demonstrated deep space optical communications, transmitting data from distances up to 350 million kilometers, exceeding technical goals.[56] The spacecraft's magnetometer instrument aims to detect any remanent magnetic field, which could preserve evidence of past dynamo activity in a molten metallic core during Psyche's early history.[57] Such measurements would provide insights into the asteroid's internal differentiation and collisional evolution without delving into broader theories.[50](21) Lutetia and Others

(21) Lutetia, with a mean diameter of 98 km, exemplifies an M-type asteroid blending metallic and silicate components.[58] The Rosetta spacecraft's flyby in July 2010 measured its bulk density at 3.4 ± 0.3 g/cm³, indicating a composition richer in metals than typical carbonaceous asteroids but consistent with enstatite chondrites. Spectral analysis from the VIRTIS instrument revealed surface materials including metallic iron-nickel and enstatite-like silicates, suggesting Lutetia as a primitive body with partial differentiation rather than a pure metallic core remnant. Another prominent example is (22) Kalliope, a larger M-type asteroid approximately 166 km in diameter that hosts a binary system with its moon Linus, discovered through adaptive optics imaging.[59] The system's mass, derived from mutual eclipse observations and orbital perturbations of Linus, yields a bulk density of 4.4 ± 0.46 g/cm³ (as of 2022) for Kalliope, supporting a metallic-rich interior with possible silicate mantle remnants.[60] This density, combined with its M-type spectrum, highlights Kalliope's potential as a differentiated planetesimal, where the moon may have formed from collisional debris. (216) Kleopatra stands out for its distinctive dog-bone shape, revealed by radar imaging in 2000 and later refined through adaptive optics observations.[61] This elongated form, approximately 270 km long with an effective diameter of 120 km, suggests formation via rotational fission or major impacts.[61] Kleopatra is a binary system with two small moons, Alexhelios and Cleoselene, and its bulk density of 3.4 g/cm³ (as of 2021) indicates high metal content with significant porosity, typical of rubble-pile structures.[61] Smaller M-type asteroids further illustrate compositional diversity, particularly through high radar albedos indicative of near-pure metallic surfaces. For instance, (129) Antigone, about 113 km in diameter, exhibits a radar albedo of 0.36 ± 0.09, suggesting substantial iron-nickel content.[62] Similarly, the near-Earth M-type (78577) 2000 ED₇₁ displays radar albedos exceeding 0.3, consistent with minimal silicate admixture and highlighting potential metallic meteoroid parents among smaller bodies. These examples underscore the range from hybrid metal-silicate objects to more metallic-dominant ones in the M-type class.References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/349919153_Mass_and_Density_of_Asteroid_16_Psyche