Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

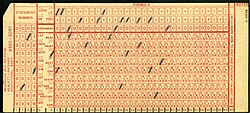

Punched card

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2023) |

A punched card (also punch card[1]) is a stiff paper-based medium used to store digital information via the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Developed over the 18th to 20th centuries, punched cards were widely used for data processing, the control of automated machines, and computing. Early applications included controlling weaving looms and recording census data.

Punched cards were widely used in the 20th century, where unit record machines, organized into data processing systems, used punched cards for data input, data output, and data storage.[2][3] The IBM 12-row/80-column punched card format came to dominate the industry. Many early digital computers used punched cards as the primary medium for input of both computer programs and data. Punched cards were used for decades before being replaced by magnetic tape data storage. While punched cards are now obsolete as a storage medium, as of 2012, some voting machines still used punched cards to record votes.[4]

Punched cards had a significant cultural impact in the 20th century. Their legacy persists in modern computing, influencing the 80-character line standard still present in some command-line interfaces and programming environments.

History

[edit]The idea of control and data storage via punched holes was developed independently on several occasions in the modern period. In most cases there is no evidence that each of the inventors was aware of the earlier work.

Precursors

[edit]

Basile Bouchon developed the control of a loom by punched holes in paper tape in 1725. The design was improved by his assistant Jean-Baptiste Falcon and by Jacques Vaucanson.[5] Although these improvements controlled the patterns woven, they still required an assistant to operate the mechanism.

In 1804 Joseph Marie Jacquard demonstrated a mechanism to automate loom operation. A number of punched cards were linked into a chain of any length. Each card held the instructions for shedding (raising and lowering the warp) and selecting the shuttle for a single pass.[6]

Semyon Korsakov was reputedly the first to propose punched cards in informatics for information store and search. Korsakov announced his new method and machines in September 1832.[7]

Charles Babbage proposed the use of "Number Cards", "pierced with certain holes and stand[ing] opposite levers connected with a set of figure wheels ... advanced they push in those levers opposite to which there are no holes on the cards and thus transfer that number together with its sign" in his description of the Calculating Engine's Store.[8] There is no evidence that he built a practical example.

In 1881, Jules Carpentier developed a method of recording and playing back performances on a harmonium using punched cards. The system was called the Mélographe Répétiteur and "writes down ordinary music played on the keyboard dans le langage de Jacquard",[9] that is as holes punched in a series of cards. By 1887 Carpentier had separated the mechanism into the Melograph which recorded the player's key presses and the Melotrope which played the music.[10][11]

20th century

[edit]At the end of the 1800s Herman Hollerith created a method for recording data on a medium that could then be read by a machine,[12][13][14][15] developing punched card data processing technology for the 1890 U.S. census.[16] This was inspired in part by Jacquard loom weaving technology and by railway punch photographs.[17] Punch photographs were quick ways for conductors to mark a ticket with a description of the ticket buyer (e.g., short or tall, dark or light hair).[17] They were used to reduce ticket fraud, as conductors could "read" the punched holes to get a basic description of the person to whom the ticket was sold.[17]

Hollerith's tabulating machines read and summarized data stored on punched cards and they began use for government and commercial data processing. Initially, these electromechanical machines only counted holes, but by the 1920s they had units for carrying out basic arithmetic operations.[18]: 124

Hollerith founded the Tabulating Machine Company (1896) which was one of four companies that were amalgamated via stock acquisition to form a fifth company, Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) in 1911, later renamed International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in 1924. Other companies entering the punched card business included The Tabulator Limited (Britain, 1902), Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft mbH (Dehomag) (Germany, 1911), Powers Accounting Machine Company (US, 1911), Remington Rand (US, 1927), and H.W. Egli Bull (France, 1931).[19] These companies, and others, manufactured and marketed a variety of punched cards and unit record machines for creating, sorting, and tabulating punched cards, even after the development of electronic computers in the 1950s.

Both IBM and Remington Rand tied punched card purchases to machine leases, a violation of the US 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act. In 1932, the US government took both to court on this issue. Remington Rand settled quickly. IBM viewed its business as providing a service and that the cards were part of the machine. IBM fought all the way to the Supreme Court and lost in 1936; the court ruled that IBM could only set card specifications.[20][21]: 300–301

"By 1937... IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day."[22] Punched cards were even used as legal documents, such as U.S. Government checks[23] and savings bonds.[24]

During World War II punched card equipment was used by the Allies in some of their efforts to decrypt Axis communications. See, for example, Central Bureau in Australia. At Bletchley Park in England, "some 2 million punched cards a week were being produced, indicating the sheer scale of this part of the operation".[25] In Nazi Germany, punched cards were used for the censuses of various regions and other purposes[26][27] (see IBM and the Holocaust).

Punched card technology developed into a powerful tool for business data-processing. By 1950 punched cards had become ubiquitous in industry and government. "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate," a warning that appeared on some punched cards distributed as documents such as checks and utility bills to be returned for processing, became a motto for the post-World War II era.[28][29]

In 1956[30] IBM signed a consent decree requiring, amongst other things, that IBM would by 1962 have no more than one-half of the punched card manufacturing capacity in the United States. Tom Watson Jr.'s decision to sign this decree, where IBM saw the punched card provisions as the most significant point, completed the transfer of power to him from Thomas Watson Sr.[21]

The Univac UNITYPER introduced magnetic tape for data entry in the 1950s. During the 1960s, the punched card was gradually replaced as the primary means for data storage by magnetic tape, as better, more capable computers became available. Mohawk Data Sciences introduced a magnetic tape encoder in 1965, a system marketed as a keypunch replacement which was somewhat successful. Punched cards were still commonly used for entering both data and computer programs until the mid-1980s when the combination of lower cost magnetic disk storage, and affordable interactive terminals on less expensive minicomputers made punched cards obsolete for these roles as well.[31]: 151 However, their influence lives on through many standard conventions and file formats. The terminals that replaced the punched cards, the IBM 3270 for example, displayed 80 columns of text in text mode, for compatibility with existing software. Some programs still operate on the convention of 80 text columns, although fewer and fewer do as newer systems employ graphical user interfaces with variable-width type fonts.

Nomenclature

[edit]

The terms punched card, punch card, and punchcard were all commonly used, as were IBM card and Hollerith card (after Herman Hollerith).[1] IBM used "IBM card" or, later, "punched card" at first mention in its documentation and thereafter simply "card" or "cards".[33][34] Specific formats were often indicated by the number of character positions available, e.g. 80-column card. A sequence of cards that is input to or output from some step in an application's processing is called a card deck or simply deck. The rectangular, round, or oval bits of paper punched out were called chad (chads) or chips (in IBM usage). Sequential card columns allocated for a specific use, such as names, addresses, multi-digit numbers, etc., are known as a field. The first card of a group of cards, containing fixed or indicative information for that group, is known as a master card. Cards that are not master cards are detail cards.

Formats

[edit]The Hollerith punched cards used for the 1890 U.S. census were blank.[35] Following that, cards commonly had printing such that the row and column position of a hole could be easily seen. Printing could include having fields named and marked by vertical lines, logos, and more.[36] "General purpose" layouts (see, for example, the IBM 5081 below) were also available. For applications requiring master cards to be separated from following detail cards, the respective cards had different upper corner diagonal cuts and thus could be separated by a sorter.[37] Other cards typically had one upper corner diagonal cut so that cards not oriented correctly, or cards with different corner cuts, could be identified.

Hollerith's early cards

[edit]

Herman Hollerith was awarded three patents[39] in 1889 for electromechanical tabulating machines. These patents described both paper tape and rectangular cards as possible recording media. The card shown in U.S. patent 395,781 of January 8 was printed with a template and had hole positions arranged close to the edges so they could be reached by a railroad conductor's ticket punch, with the center reserved for written descriptions. Hollerith was originally inspired by railroad tickets that let the conductor encode a rough description of the passenger:

I was traveling in the West and I had a ticket with what I think was called a punch photograph...the conductor...punched out a description of the individual, as light hair, dark eyes, large nose, etc. So you see, I only made a punch photograph of each person.[18]: 15

When use of the ticket punch proved tiring and error-prone, Hollerith developed the pantograph "keyboard punch". It featured an enlarged diagram of the card, indicating the positions of the holes to be punched. A printed reading board could be placed under a card that was to be read manually.[35]: 43

Hollerith envisioned a number of card sizes. In an article he wrote describing his proposed system for tabulating the 1890 U.S. census, Hollerith suggested a card 3 by 5+1⁄2 inches (7.6 by 14.0 cm) of Manila stock "would be sufficient to answer all ordinary purposes."[40] The cards used in the 1890 census had round holes, 12 rows and 24 columns. A reading board for these cards can be seen at the Columbia University Computing History site.[41] At some point, 3+1⁄4 by 7+3⁄8 inches (83 by 187 mm) became the standard card size. These are the dimensions of the then-current paper currency of 1862–1923.[42] This size was needed in order to use available banking-type storage for the 60,000,000 punched cards to come nationwide.[41]

Hollerith's original system used an ad hoc coding system for each application, with groups of holes assigned specific meanings, e.g. sex or marital status. His tabulating machine had up to 40 counters, each with a dial divided into 100 divisions, with two indicator hands; one which stepped one unit with each counting pulse, the other which advanced one unit every time the other dial made a complete revolution. This arrangement allowed a count up to 9,999. During a given tabulating run counters were assigned specific holes or, using relay logic, combination of holes.[40]

Later designs led to a card with ten rows, each row assigned a digit value, 0 through 9, and 45 columns.[43] This card provided for fields to record multi-digit numbers that tabulators could sum, instead of their simply counting cards. Hollerith's 45 column punched cards are illustrated in Comrie's The application of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine to Brown's Tables of the Moon.[44]

IBM 80-column format and character codes

[edit]

By the late 1920s, customers wanted to store more data on each punched card. In 1927,[45] Thomas J. Watson Sr., IBM's head, asked two of his top inventors, Clair D. Lake and J. Royden Pierce, to independently develop ways to increase data capacity without increasing the size of the punched card.[46] Pierce wanted to keep round holes and 45 columns but to allow each column to store more data; Lake suggested rectangular holes, which could be spaced more tightly, allowing 80 columns per punched card, thereby nearly doubling the capacity of the older format.[47] Watson picked the latter solution, introduced as The IBM Card, in part because it was compatible with existing tabulator designs and in part because it could be protected by patents and give the company a distinctive advantage,[48] and "competitors using mechanical sensing of holes would find it difficult to make the change".[45]

Introduced in 1928, the IBM card format[49] had rectangular holes, 80 columns, and 10 rows.[50] Card size is 7+3⁄8 by 3+1⁄4 inches (187 by 83 mm). The cards are made of smooth stock, 0.007 inches (180 μm) thick. There are about 143 cards to the inch (56/cm). In 1930, the IBM card format had rectangular holes, 80 columns, and 12 rows, with two more rows added to the top of the card for alphabetic coding.[45] In 1964, IBM changed from square to round corners.[51] They come typically in boxes of 2,000 cards[52] or as continuous form cards. Continuous form cards could be both pre-numbered and pre-punched for document control (checks, for example).[53]

Initially designed to record responses to yes–no questions, support for numeric, alphabetic and special characters was added through the use of columns and zones. The top three positions of a column are called zone punching positions, 12 (top), 11, and 0 (0 may be either a zone punch or a digit punch).[54] For decimal data the lower ten positions are called digit punching positions, 0 (top) through 9.[54] An arithmetic sign can be specified for a decimal field by overpunching the field's rightmost column with a zone punch: 12 for plus, 11 for minus (CR). For Pound sterling pre-decimalization currency a penny column represents the values zero through eleven; 10 (top), 11, then 0 through 9 as above. An arithmetic sign can be punched in the adjacent shilling column.[55]: 9 Zone punches had other uses in processing, such as indicating a master card.[56]

Diagram:[57]

_______________________________________________ / &-0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQR/STUVWXYZ 12| x xxxxxxxxx 11| x xxxxxxxxx 0| x xxxxxxxxx 1| x x x x 2| x x x x 3| x x x x 4| x x x x 5| x x x x 6| x x x x 7| x x x x 8| x x x x 9| x x x x |________________________________________________

Note: The 11 and 12 zones were also called the X and Y zones, respectively.

In 1931, IBM began introducing upper-case letters and special characters (Powers-Samas had developed the first commercial alphabetic punched card representation in 1921).[58][59][nb 1] The 26 letters have two punches (zone [12,11,0] + digit [1–9]). The languages of Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Portugal and Finland require up to three additional letters; their punching is not shown here.[60]: 88–90 Most special characters have two or three punches (zone [12,11,0, or none] + digit [2–7] + 8); a few special characters were exceptions: "&" is 12 only, "-" is 11 only, and "/" is 0 + 1). The Space character has no punches.[60]: 38 The information represented in a column by a combination of zones [12, 11, 0] and digits [0–9] is dependent on the use of that column. For example, the combination "12-1" is the letter "A" in an alphabetic column, a plus signed digit "1" in a signed numeric column, or an unsigned digit "1" in a column where the "12" has some other use. The introduction of EBCDIC in 1964 defined columns with as many as six punches (zones [12,11,0,8,9] + digit [1–7]). IBM and other manufacturers used many different 80-column card character encodings.[61][62] A 1969 American National Standard defined the punches for 128 characters and was named the Hollerith Punched Card Code (often referred to simply as Hollerith Card Code), honoring Hollerith.[60]: 7

For some computer applications, binary formats were used, where each hole represented a single binary digit (or "bit"), every column (or row) is treated as a simple bit field, and every combination of holes is permitted.

For example, on the IBM 701[63] and IBM 704,[64] card data was read, using an IBM 711, into memory in row binary format. For each of the twelve rows of the card, 72 of the 80 columns, skipping the other eight, would be read into two 36-bit words, requiring 864 bits to store the whole card; a control panel was used to select the 72 columns to be read. Software would translate this data into the desired form. One convention was to use columns 1 through 72 for data, and columns 73 through 80 to sequentially number the cards, as shown in the picture above of a punched card for FORTRAN. Such numbered cards could be sorted by machine so that if a deck was dropped the sorting machine could be used to arrange it back in order. This convention continued to be used in FORTRAN, even in later systems where the data in all 80 columns could be read.

The IBM card readers 3504, 3505 and the multifunction unit 3525 used a different encoding scheme for column binary data, also known as card image, where each column, split into two rows of 6 (12–3 and 4–9) was encoded into two 8-bit bytes, holes in each group represented by bits 2 to 7 (MSb numbering, bit 0 and 1 unused ) in successive bytes. This required 160 8-bit bytes, or 1280 bits, to store the whole card.[65]

As an aid to humans who had to deal with the punched cards, the IBM 026 and later 029 and 129 key punch machines could print human-readable text above each of the 80 columns.

As a prank, punched cards could be made where every possible punch position had a hole. Such "lace cards" lacked structural strength, and would frequently buckle and jam inside the machine.[66]

The IBM 80-column punched card format dominated the industry, becoming known as just IBM cards, even though other companies made cards and equipment to process them.[67]

One of the most common punched card formats is the IBM 5081 card format, a general purpose layout with no field divisions. This format has digits printed on it corresponding to the punch positions of the digits in each of the 80 columns. Other punched card vendors manufactured cards with this same layout and number.

IBM Stub card and Short card formats

[edit]Long cards were available with a scored stub on either end which, when torn off, left an 80 column card. The torn off card is called a stub card.

80-column cards were available scored, on either end, creating both a short card and a stub card when torn apart. Short cards can be processed by other IBM machines.[53][68] A common length for stub cards was 51 columns. Stub cards were used in applications requiring tags, labels, or carbon copies.[53]

IBM 40-column Port-A-Punch card format

[edit]According to the IBM Archive: IBM's Supplies Division introduced the Port-A-Punch in 1958 as a fast, accurate means of manually punching holes in specially scored IBM punched cards. Designed to fit in the pocket, Port-A-Punch made it possible to create punched card documents anywhere. The product was intended for "on-the-spot" recording operations—such as physical inventories, job tickets and statistical surveys—because it eliminated the need for preliminary writing or typing of source documents.[69]

-

IBM Port-A-Punch

-

FORTRAN Port-A-Punch card. Compiler directive "SQUEEZE" removed the alternating blank columns from the input.

-

Port-a-punch

IBM 96-column format

[edit]

In 1969 IBM introduced a new, smaller, round-hole, 96-column card format along with the IBM System/3 low-end business computer. These cards have tiny, 1 mm diameter circular holes, smaller than those in paper tape. Data is stored in 6-bit BCD, with three rows of 32 characters each, or 8-bit EBCDIC. In this format, each column of the top tiers are combined with two punch rows from the bottom tier to form an 8-bit byte, and the middle tier is combined with two more punch rows, so that each card contains 64 bytes of 8-bit-per-byte binary coded data.[70] As in the 80 column card, readable text was printed in the top section of the card. There was also a fourth row of 32 characters that could be printed. This format was never widely used; it was IBM-only, but they did not support it on any equipment beyond the System/3, where it was quickly superseded by the 1973 IBM 3740 Data Entry System using 8-inch floppy disks.

The format was however recycled in 1978 when IBM re-used the mechanism in its IBM 3624 ATMs as print-only receipt printers.

Powers/Remington Rand/UNIVAC 90-column format

[edit]

The Powers/Remington Rand card format was initially the same as Hollerith's; 45 columns and round holes. In 1930, Remington Rand leap-frogged IBM's 80 column format from 1928 by coding two characters in each of the 45 columns – producing what is now commonly called the 90-column card.[31]: 142 There are two sets of six rows across each card. The rows in each set are labeled 0, 1/2, 3/4, 5/6, 7/8 and 9. The even numbers in a pair are formed by combining that punch with a 9 punch. Alphabetic and special characters use three or more punches.[71][72]

Powers-Samas formats

[edit]The British Powers-Samas company used a variety of card formats for their unit record equipment. They began with 45 columns and round holes. Later 36-, 40- and 65-column cards were provided. A 130-column card was also available – formed by dividing the card into two rows, each row with 65 columns and each character space with five punch positions. A 21-column card was comparable to the IBM Stub card.[55]: 47–51

Mark sense format

[edit]

Mark sense (electrographic) cards, developed by Reynold B. Johnson at IBM,[73] have printed ovals that could be marked with a special electrographic pencil. Cards would typically be punched with some initial information, such as the name and location of an inventory item. Information to be added, such as quantity of the item on hand, would be marked in the ovals. Card punches with an option to detect mark sense cards could then punch the corresponding information into the card.

Aperture format

[edit]

Aperture cards have a cut-out hole on the right side of the punched card. A piece of 35 mm microfilm containing a microform image is mounted in the hole. Aperture cards are used for engineering drawings from all engineering disciplines. Information about the drawing, for example the drawing number, is typically punched and printed on the remainder of the card.

Manufacturing

[edit]

IBM's Fred M. Carroll[74] developed a series of rotary presses that were used to produce punched cards, including a 1921 model that operated at 460 cards per minute (cpm). In 1936 he introduced a completely different press that operated at 850 cpm.[22][75] Carroll's high-speed press, containing a printing cylinder, revolutionized the company's manufacturing of punched cards.[76] It is estimated that between 1930 and 1950, the Carroll press accounted for as much as 25 percent of the company's profits.[21]

Discarded printing plates from these card presses, each printing plate the size of an IBM card and formed into a cylinder, often found use as desk pen/pencil holders, and even today are collectible IBM artifacts (every card layout[77] had its own printing plate).

In the mid-1930s a box of 1,000 cards cost $1.05 (equivalent to $24 in 2024).[78]

Cultural impact

[edit]

While punched cards have not been widely used for generations, the impact was so great for most of the 20th century that they still appear from time to time in popular culture. For example:

- Accommodation of people's names: The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit[79][80]

- Artist and architect Maya Lin in 2004 designed a public art installation at Ohio University, titled "Input", that looks like a punched card from the air.[81]

- Tucker Hall at the University of Missouri – Columbia features architecture that is rumored to be influenced by punched cards. Although there are only two rows of windows on the building, a rumor holds that their spacing and pattern will spell out "M-I-Z beat k-U!" on a punched card, making reference to the university and state's rivalry with neighboring state Kansas.[82]

- At the University of Wisconsin – Madison, the exterior windows of the Engineering Research Building[83] were modeled after a punched card layout, during its construction in 1966.

- At the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, a portion of the exterior of Gamble Hall (College of Business and Public Administration), has a series of light-colored bricks that resembles a punched card spelling out "University of North Dakota."[84]

- In the 1964–1965 Free Speech Movement, punched cards became a

metaphor... symbol of the "system"—first the registration system and then bureaucratic systems more generally ... a symbol of alienation ... Punched cards were the symbol of information machines, and so they became the symbolic point of attack. Punched cards, used for class registration, were first and foremost a symbol of uniformity. .... A student might feel "he is one of out of 27,500 IBM cards" ... The president of the Undergraduate Association criticized the University as "a machine ... IBM pattern of education."... Robert Blaumer explicated the symbolism: he referred to the "sense of impersonality... symbolized by the IBM technology."...

- — Steven Lubar[28]

- A legacy of the 80 column punched card format is that a display of 80 characters per row was a common choice in the design of character-based terminals.[85][86] As of September 2014, some character interface defaults, such as the command prompt window's width in Microsoft Windows, remain set at 80 columns and some file formats, such as FITS, still use 80-character card images. The two-line element set format for tracking objects in Earth orbit is based on punch cards.

- In Arthur C. Clarke's early short story "Rescue Party", the alien explorers find a "... wonderful battery of almost human Hollerith analyzers and the five thousand million punched cards holding all that could be recorded on each man, woman and child on the planet".[87] Writing in 1946, Clarke, like almost all SF authors, had not then foreseen the development and eventual ubiquity of the computer.

- In Philip K. Dick's 1956 novelette "The Minority Report", convicts predicted by Precogs are printed in punched cards.[citation needed]

- In "I.B.M.", the final track of her album This Is a Recording, comedian Lily Tomlin gives instructions that, if followed, would purportedly shrink the holes on a punch card (used by AT&T at the time for customer billing), making it unreadable.

Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate

[edit]A common example of the requests often printed on punched cards which were to be individually handled, especially those intended for the public to use and return is "Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate" (in the UK "Do not bend, spike, fold or mutilate").[28]: 43–55 Coined by Charles A. Phillips,[88] it became a motto[89] for the post–World War II era (even though many people had no idea what spindle meant), and was widely mocked and satirized. Some 1960s students at Berkeley wore buttons saying: "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate. I am a student".[90] The motto was also used for a 1970 book by Doris Miles Disney[91] with a plot based around an early computer dating service and a 1971 made-for-TV movie based on that book, and a similarly titled 1967 Canadian short film, Do Not Fold, Staple, Spindle or Mutilate.

Standards

[edit]

- ANSI INCITS 21-1967 (R2002), Rectangular Holes in Twelve-Row Punched Cards (formerly ANSI X3.21-1967 (R1997)) Specifies the size and location of rectangular holes in twelve-row 3+1⁄4-inch-wide (83 mm) punched cards.

- ANSI X3.11-1990 American National Standard Specifications for General Purpose Paper Cards for Information Processing

- ANSI X3.26-1980 (R1991) Hollerith Punched Card Code

- ISO 1681:1973 Information processing – Unpunched paper cards – Specification

- ISO 6586:1980 Data processing – Implementation of the ISO 7- bit and 8- bit coded character sets on punched cards. Defines ISO 7-bit and 8-bit character sets on punched cards as well as the representation of 7-bit and 8-bit combinations on 12-row punched cards. Derived from, and compatible with, the Hollerith Code, ensuring compatibility with existing punched card files.

Punched card devices

[edit]Processing of punched cards was handled by a variety of machines, including:

- Keypunches—machines with a keyboard that punched cards from operator entered data.

- Unit record equipment—machines that process data on punched cards. Employed prior to the widespread use of digital computers. Includes card sorters, tabulating machines and a variety of other machines

- Computer punched card reader—a computer input device used to read executable computer programs and data from punched cards under computer control. Card readers, found in early computers, could read up to 100 cards per minute, while traditional "high-speed" card readers could read about 1,000 cards per minute.[92]

- Computer card punch—a computer output device that punches holes in cards under computer control.

- Voting machines—used into the 21st century

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Special characters are non-alphabetic, non-numeric, such as "&#,$.-/@%*?"

References

[edit]- ^ a b Pinker, Steven Arthur (2007). The Stuff of Thought. Viking. p. 362. (NB. Notes the loss of -ed in pronunciation as it did in ice cream, mincemeat, and box set, formerly iced cream, minced meat, and boxed set.)

- ^ Cortada, James W. [at Wikidata] (1993). Before The Computer: IBM, NCR, Burroughs, & Remington Rand & The Industry They Created, 1865–1965. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-63008-3.

- ^ Brooks, Frederick Phillips; Iverson, Kenneth Eugene (1963). Automatic Data Processing. Wiley. p. 94.

semiautomatic

- ^ "Nightly News Aired on 2012-12-27 – Punch card voting lingers". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2017-04-19.

- ^ Razy, Claudius (1913). Étude analytique des petits modèles de métiers exposés au musée des tissus [Analytical study of small loom models exhibited at the museum of fabrics] (in French). Lyon, France: Musée Historique des Tissus. p. 120.

- ^ Essinger, James (2007-03-29). Jacquard's Web: How a Hand-loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age. OUP Oxford. pp. 35–40. ISBN 978-0-19280578-2.

- ^ "1801: Punched cards control Jacquard loom". computerhistory.org. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ Babbage, Charles (1837-12-26). "On the Mathematical Powers of the Calculating Engine". The Origins of Digital Computers. pp. 19–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61812-3_2. ISBN 978-3-642-61814-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Southgate, Thomas Lea (1881). "On Various Attempts That Have Been Made to Record Extemporaneous Playing". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 8 (1): 189–196. doi:10.1093/jrma/8.1.189.

- ^ Seaver, Nicholas Patrick (June 2010). A Brief History of Re-performance (PDF) (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 34. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- ^ "The Reproducing Piano – Early Experiments". www.pianola.com. The Pianola Institute. 2016. Retrieved 2024-06-09.

At this early stage, the corresponding playback mechanism, the Mélotrope, was permanently installed inside the same harmonium used for the recording process, but by 1887 Carpentier had modified both devices, restricting the range to three octaves, allowing for the Mélotrope to be attached to any style of keyboard instrument, and designing and constructing an automatic perforating machine for mass production.

- ^ Hollerith, H. (April 1889). "An Electric Tabulating System". The Quarterly. X (16). School of Mines, Columbia University: 238–255.

- ^ Randell, Brian, ed. (1982). The Origins of Digital Computers, Selected Papers (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-11319-3.

- ^ US patent 395782, Hollerith, Herman, "Art of compiling statistics", issued 1889-01-08

- ^ "Art of compiling statistics". Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ da Cruz, Frank (2019-08-28). "Herman Hollerith". Columbia University Computing History. Columbia University. Retrieved 2024-06-09.

After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards...

- ^ a b c Sobel, Robert (1981). I.B.M., colossus in transition. New York: Times Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8129-1000-1.

- ^ a b Austrian, Geoffrey D. (1982). Herman Hollerith: The Forgotten Giant of Information Processing. Columbia University Press. pp. 15, 124, 418–. ISBN 978-0-231-05146-0.

- ^ A History of Sperry Rand Corporation (4th ed.). Sperry Rand. 1967. p. 32.

- ^ "International Business Machines Corp. v. United States, 298 U.S. 131". Justia. 1936.

- ^ a b c Belden, Thomas; Belden, Marva (1962). The Lengthening Shadow: The Life of Thomas J. Watson. Little, Brown & Company. pp. 300–301.

- ^ a b "IBM Archive: Endicott card manufacturing". IBM. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Lubar, Steven (1993). InfoCulture: The Smithsonian Book of Information Age Inventions. Houghton Mifflin. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-395-57042-5.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Supplies Division history". IBM. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03.

1962: 20th year […] producing savings bonds […] 1964: $75 savings bond […] produce

- ^ Block, H. "Wartime Building History". Codes and Ciphers Heritage Trust.

- ^ Luebke, David Martin [at Wikidata]; Milton, Sybil Halpern [in German] (Autumn 1994). "Locating the victim: An overview of census-taking, tabulation technology and persecution in Nazi Germany". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 16 (3). IEEE: 25–. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1994.298418. S2CID 16010272.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2009) [2001]. IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation (Second ed.). Washington, DC, USA: Dialog Press. OCLC 958727212.

- ^ a b c Lubar, Steven (Winter 1992). "Do Not Fold, Spindle Or Mutilate: A Cultural History Of The Punch Card" (PDF). Journal of American Culture. 15 (4): 43–55. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.1992.1504_43.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2011-06-11. pp. 43–55:

Security checks issued starting in 1936 […]

(13 pages); Lubar, Steven (May 1991). "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate: A cultural history of the punch card". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2006-08-30. (NB. An earlier version of this paper was presented to the Bureau of the Census's Hollerith Machine Centennial Celebration on 1990-06-20.) - ^ Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Cards – A brief illustrated technical history". Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "Justice Department agrees to terminate last provisions of IBM consent decree in stages ending 5 years from today" (Press release). Justice Department. 1996-07-02. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ a b Aspray, William [in German], ed. (1990). Computing before Computers. Iowa State University Press. pp. 142, 151. ISBN 978-0-8138-0047-9.

- ^ "Punched Cards". miami.edu. University of Miami. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

Once the cards were assembled in order in a deck, the programmer would usually draw a long diagonal line across the top edges of the cards, so that if ever one got out of order it would easily be noticed

- ^ IBM 519 Principles of Operation. IBM. 1946. Form 22-3292-5.

An important function in IBM Accounting is the automatic preparation of IBM cards.

- ^ Reference Manual 1401 Data Processing System (PDF). IBM. April 1962. p. 10. A24-1403-5.

The IBM 1402 Card Read-Punch provides the system with simultaneous punched-card input and output. This unit has two card feeds.

- ^ a b Truesdell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census 1890–1940. US GPO. p. 43. Includes extensive, detailed, description of Hollerith's first machines and their use for the 1890 census.

- ^ The Design of IBM Cards (PDF). IBM. 1956. 22-5526-4.

- ^ Reference Manual – IBM 82, 83, and 84 Sorters (PDF). IBM. July 1962. p. 25. A24-1034.

- ^ "Hollerith's Electric Tabulating Machine". Railroad Gazette. 1895-04-19. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20. Retrieved 2015-06-04 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ U.S. patent 395,781, U.S. patent 395,782, U.S. patent 395,783

- ^ a b Hollerith, Herman (April 1889). da Cruz, Frank (ed.). "An Electric Tabulating System". The Quarterly. 10 (16). School of Mines, Columbia University: 245.

- ^ a b da Cruz, Frank (2019-12-26). "Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator". Columbia University Computing History. Columbia University. Retrieved 2024-06-09.

- ^ "Large-Size U.S. Paper Money". Littleton Coin Company. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ^ Bashe, Charles J.; Johnson, Lyle R.; Palmer, John H.; Pugh, Emerson W. (1986). IBM's Early Computers. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: The MIT Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-262-02225-5. (NB. Also see pages 5–14 for additional information on punched cards.)

- ^ Comrie, Leslie John (1932). "The application of the Hollerith tabulating machine to Brown's tables of the moon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (7): 694–707. Bibcode:1932MNRAS..92..694C. doi:10.1093/mnras/92.7.694.

- ^ a b c Pugh, Emerson W.; Heide, Lars (2015-01-09). "Early Punched Card Equipment, 1880 - 1951". Engineering and Technology History Wiki. Retrieved 2025-08-02.

In 1927, IBM President, Thomas J. Watson, assigned two of his top inventors, Clair D. Lake and J. Royden Pierce, the task of creating a punched card with greater capacity than the forty-five-column card that was then standard for IBM and Remington Rand, Inc. Greater capacity was needed for many accounting applications.

- ^ "The punched card". www.ibm.com | IBM. Retrieved 2025-08-02.

- ^ U.S. Patent 1,772,492, Record Sheet for Tabulating Machines, C. D. Lake, filed 1928-06-20

- ^ "IBM 100 – The IBM Punched Card". IBM. 2012-03-07. Archived from the original on 2014-04-25. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "IBM Archives: 1928". Archived from the original on 2015-01-03.

- ^ Pugh – Building IBM – page 49.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Old and new punched cards". Archived from the original on 2015-01-03.

- ^ Donald B. Boyd (2007). "How Computational Chemistry Became Important in the Pharmaceutical Industry". In Kenny B. Lipkowitz; Thomas R. Cundari; Donald B. Boyd (eds.). Reviews in Computational Chemistry, Volume 23. Wiley & Son. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-470-08201-0.

- ^ a b c Principles of IBM Accounting. IBM. 1953. 224-5527-2.

- ^ a b Punched card Data Processing Principles. IBM. 1961. p. 3.

- ^ a b Cemach, Harry P. (1951). The Elements of Punched Card Accounting. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd. pp. 9, 47–51, 137–. Machine illustrations were provided by Power-Samas Accounting Machines and British Tabulating Machine Co.

- ^ IBM Operator's Guide (PDF). IBM. July 1959. p. 141. A24-1010.

Master Card: The first card of a group containing fixed or indicative information for that group

- ^ Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Card Codes". Cs.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Rojas, Raúl, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of Computers and Computer History. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 656.

- ^ Pugh, Emerson W. (1995). Building IBM: Shaping and Industry and Its Technology. MIT Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-262-16147-3.

- ^ a b c Mackenzie, Charles E. (1980). Coded Character Sets, History and Development (PDF). The Systems Programming Series (1 ed.). Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 7, 38, 88–90. ISBN 978-0-201-14460-4. LCCN 77-90165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- ^ Winter, Dik T. "80-column Punched Card Codes". Archived from the original on 2007-04-08. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^ Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Card Codes". Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Principles of Operation, Type 701 and Associated Equipment (PDF). IBM. 1953. pp. 34–36. 24-6042-1.

- ^ 704 Electronic Data Processing Machine – Manual of Operation (PDF). New York City: IBM. 1955. pp. 39–50. 24-6661-2. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ "Card Image". IBM 3504 Card Reader/IBM 3505 Card Reader and IBM 3525 Card Punch Subsystem (PDF) (6th ed.). Rochester, Minnesota: IBM. October 1974. p. 8. GA21-9124-5. Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S., ed. (1991). The New Hacker's Dictionary. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT Press. p. 219.

- ^ Maxfield, Clive "Max" (2011-10-13). "How it was: Paper tapes and punched cards". EE Times. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ IBM 24 Card Punch, IBM 26 Printing Card Punch Reference Manual (PDF). October 1965. p. 26. A24-0520-3.

The variable-length card feed feature on the 24 or 26 allows the processing of 51-, 60-, 66-, and 80-column cards (Figure 20)

- ^ "IBM Archives: Port-A-Punch". 03.ibm.com. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Winter, Dik T. "96-column Punched Card Code". Archived from the original on 2007-04-15. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^ "The Punched Card". Quadibloc.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Winter, Dik T. "90-column Punched Card Code". Archived from the original on 2005-02-28. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence M. (1998-09-18). "Reynold Johnson, 92, Pioneer In Computer Hard Disk Drives". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Fred M. Carroll". IBM Builders. IBM. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "IBM Archives: Fred M. Carroll". IBM's ASCC. IBM. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "IBM Archives: (IBM) Carroll Press". Antique attic, vol.3. IBM. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "IBM Archives: 1939 Layout department". IBM attire. IBM. 2003-01-23. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Cortada, James W. [at Wikidata] (2019). IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon. MIT Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-262-03944-4.

- ^ Tyler, Theodore (1968). The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit. Doubleday Science Fiction.

- ^ Brown, Betsy (1987-12-06). "Westchester Bookcase". The New York Times.

Edward Ziegler […] an editor at the Reader's Digest […] wrote a science fiction novel, The Man Whose Name Wouldn't Fit, under the pen name Theodore Tyler

- ^ "Mayalin.com". Mayalin.com. 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "Mizzou Alumni Association – Campus Traditions". Mizzou Alumni Association. Tucker Hall. Retrieved 2024-06-09.

- ^ "University of Wisconsin-Madison Buildings". Fpm.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-05.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Photo of Gamble Hall by gatty790". Panoramio.com. Archived from the original on 2013-07-15. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ "All About CRT Display Terminals" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Rader, Ron (1981-10-26). "Big Screen, 132-Column Units Setting Trend". Computerworld. Special Report p. 41. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Clarke, Arthur C. (May 1946). Rescue Party. Baen Books.

- ^ Lee, John A. N. "Charles A. Phillips". Computer Pioneers. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. p. 557. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ "Fold, spindle, or mutilate".

At the bottom of the bill, it said […] and Jane, in her anger, […]

- ^ Albertson, Dean (1975). Rebels or Revolutionaries? Student Movements of the 1960s. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-67118737-8. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ Disney, Doris Miles (1970). Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate. Doubleday Crime Club. p. 183.

- ^ Donovan, John J. (1972). Systems Programming. McGraw-Hill. p. 351. ISBN 0-07-085175-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Fierheller, George A. (2014-02-07). Do not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate: The "hole" story of punched cards (PDF). Markham, Ontario, Canada: Stewart Publishing & Printing. ISBN 978-1-894183-86-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2018-04-03. (NB. An accessible book of recollections (sometimes with errors), with photographs and descriptions of many unit record machines.)

- How to Succeed At Cards (Film). IBM. 1963. (NB. An account of how IBM Cards are manufactured, with special emphasis on quality control.)

- Murray, Francis Joseph (1961). "Chapter 6 Punched Cards". Mathematical Machines: Digital Computers. Vol. 1. Columbia University Press. (NB. Includes a description of Samas punched cards and illustration of an Underwood Samas punched card.)

- Solomon Jr., Martin B.; Lovan, Nora Geraldine (1967). Annotated Bibliography of Films in Automation, Data Processing, and Computer Science. University of Kentucky.

- Dyson, George (1999-03-01). "The Undead". Wired. Vol. 7, no. 3. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2017-07-04. (NB. Article about use of punched cards in the 1990s (Cardamation).)

- Williams, Robert V. (2002). "Punched Cards: A Brief Tutorial". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing: Web Extra. 24 (2). IEEE. Archived from the original on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2015-03-26.

External links

[edit]- An Emulator for Punched cards

- Collected Information on Punched Card Codes, Atlas Computer Laboratory, 1960

- Brian De Palma (Director) (1961). 660124: The Story of an IBM Card (Film).

- Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Cards". Retrieved 2006-10-20. (Collection shows examples of left, right, and no corner cuts.)

- Punched Cards – a collection at Gesellschaft für Software mbH

- UNIVAC Punch Card Gallery (Shows examples of both left and right corner cuts.)

Punched card

View on GrokipediaHistory

Precursors in Mechanical Automation

The Jacquard loom, demonstrated by French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard in Lyon in 1801 and patented in 1804, marked a pivotal advancement in mechanical automation through the use of punched cards. This apparatus utilized chains of punched pasteboard cards, each representing a single row of a weaving pattern, to selectively lift individual warp threads via needles guided by the presence or absence of holes.[2][6] The mechanism translated hole patterns into mechanical actions, allowing unskilled operators to produce intricate silk designs that previously demanded expert weavers, thereby enhancing productivity in the textile industry.[7] By linking multiple cards into endless chains, the loom enabled the reproduction of complex, repeatable sequences without continuous manual adjustment, establishing punched cards as a durable medium for encoding operational instructions.[8] This approach demonstrated the feasibility of mechanical devices executing predefined control signals stored on removable media, independent of electrical or fluid power sources.[9] In the 1830s, British mathematician Charles Babbage incorporated similar perforated cards into his proposed Analytical Engine, a mechanical computing device designed for general arithmetic operations. Babbage specified three card types—operation cards for directing computations, variable cards for specifying memory locations, and number cards for inputting data—directly inspired by the Jacquard system's programmability.[10][11] Although the engine was never fully built due to technical and funding challenges, its conceptual reliance on punched cards highlighted their versatility for both instructional sequencing and data representation in automated calculation.[12] These early implementations underscored punched cards' role in providing persistent, interchangeable control mechanisms, laying empirical groundwork for subsequent automation by enabling precise, error-resistant replication of mechanical behaviors across repeated cycles.[2]Invention for Statistical Tabulation

In the late 1880s, Herman Hollerith developed a system of punched cards featuring rectangular holes punched in specific positions to encode demographic and statistical data, enabling mechanized tabulation for the U.S. Census Bureau. This innovation addressed the delays experienced in processing the 1880 census, which took over seven years for full tabulation due to manual methods. Hollerith's approach used cards measuring approximately 6 inches wide by 3¼ inches high, with printed templates guiding punches to represent variables such as age, occupation, and marital status through numeric codes across multiple columns and rows.[13] Hollerith secured U.S. Patent 395,782 for the "Art of Compiling Statistics" on January 8, 1889, following a competitive trial in 1888 where his system demonstrated superior speed in data capture and tabulation of sample records, completing transcription in 72.5 hours and tabulation in 5.5 hours compared to days or weeks for rivals. Awarded the contract for the 1890 census, his electric tabulating machines read cards via electrical contacts detecting holes, aggregating counts and sorting data into bins without manual intervention for basic tallies. This established a direct causal mechanism for scalable statistical analysis, shifting from labor-intensive hand-counting to automated processing.[14][15] The system processed approximately 63 million cards for the 1890 census, delivering population totals within months and completing the full report in under three years—versus seven years for 1880—while operating under budget and earning Hollerith a medal at the 1893 World's Fair. By mechanizing data verification and aggregation, it reduced error rates and enabled rapid insights into population dynamics, demonstrating empirical efficiency gains of roughly tenfold in tabulation speed for aggregate statistics.[13][3]Commercial Expansion and Industry Dominance

Following the successful application of punched card tabulation to the 1890 U.S. Census, Herman Hollerith established the Tabulating Machine Company in 1896 to lease and sell his systems for commercial data processing beyond government use.[16] The firm capitalized on the technology's ability to mechanize sorting and counting, initially targeting repetitive administrative tasks where manual methods proved inefficient and error-prone.[13] In 1911, the Tabulating Machine Company merged into the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR), a consolidation of several firms under financier Charles Ranlett Flint, with Hollerith's punched card operations forming its core revenue driver.[16] CTR rebranded as International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in 1924, achieving market dominance in punched card equipment by the late 1920s through aggressive leasing models, proprietary card designs incompatible with competitors, and superior sales infrastructure that outpaced rivals like the Powers Accounting Machine Company.[17] This control stemmed from economic incentives tied to recurring card purchases and machine rentals, creating vendor lock-in that boosted IBM's share of the burgeoning data processing sector.[18] Punched cards gained traction in railroads for inventory tracking and traffic management, insurance firms like Prudential for policy administration starting in the 1920s, and general business payroll operations, where mechanical sorters and tabulators centralized records, reduced clerical errors from handwritten ledgers, and enabled scalable handling of growing transaction volumes.[17] [19] By facilitating rapid aggregation and verification of numerical data without full manual intervention, the systems drove administrative efficiencies in pre-electronic bureaucracies, particularly for organizations managing thousands of daily entries.[20] IBM's 1928 introduction of the 80-column rectangular-hole card format marked a pivotal standardization effort, doubling data capacity over prior round-hole designs and promoting equipment interoperability, which further entrenched its industry lead by simplifying adoption across vendors.[1] Empirical scale underscores this expansion: by 1937, IBM presses manufactured 5 to 10 million cards daily to meet demand, reflecting the technology's role as a causal enabler of large-scale mechanized accounting before magnetic and electronic alternatives emerged.[21]Integration with Early Computing

Punched cards served as a primary medium for loading programs and data into early computers, bridging mechanical tabulation with electronic computation. The Harvard Mark I, completed in 1944, incorporated punched card readers and punches as integral components for input and output operations, leveraging existing IBM tabulating machinery to handle complex calculations.[22] This integration allowed the machine to process instructions encoded on cards, supplementing its primary use of punched paper tape for sequential control.[23] By the early 1950s, electronic computers like the UNIVAC I, delivered in 1951, employed punched cards for program entry and data input, despite innovations in magnetic tape storage.[24] Programmers assembled decks of cards containing machine code or source statements, which the computer's card reader interpreted to initiate execution. This method persisted into transistorized systems, such as the IBM 1401 announced in 1959, where cards facilitated batch processing of payroll, inventory, and scientific simulations.[1] High-level languages accelerated this adoption; FORTRAN, introduced in 1957, and COBOL, standardized in 1959, enabled programmers to punch source code into cards for compilation on mainframes, generating object decks for repeated use.[25] Such decks supported verifiable execution through physical auditing—cards could be inspected, sorted, or duplicated—though sequential reading imposed inherent delays compared to random-access alternatives. Usage peaked in the 1960s, powering engineering computations, business analytics, and government data processing across industries.[26]Decline Due to Technological Succession

The obsolescence of punched cards accelerated in the 1960s with the adoption of magnetic tape and disk storage, which provided far higher data densities and resistance to mechanical wear compared to cards' limited capacity of roughly 80 bytes per 80-column IBM card. Early magnetic tapes, by contrast, stored thousands of bytes per reel, enabling compact archival of datasets that would otherwise require stacks of thousands of cards, while disks like the IBM 305 RAMAC introduced random access absent in sequential card processing.[27][1][28] Economic factors compounded this transition, as falling costs for tape and disk media in the 1970s—coupled with the ability to edit data electronically—eliminated the need for labor-intensive card production, verification, and bulky storage that occupied significant physical space. Keypunch operations, reliant on manual hole punching, saw operator employment peak at 273,000 in 1978 before declining sharply with the rise of direct terminal input by the 1980s, displacing roles tied to card handling. Manufacturing output followed suit, with U.S. producers reporting volume drops starting in the 1980s and IBM halting card production by the mid-1980s amid broader automation.[29][30][31] The last widespread institutional use ended post-2000, particularly in elections, where the Help America Vote Act of 2002 required states to replace punch card systems—blamed for issues like the 2000 Florida recount—with optical scan or direct-recording electronic alternatives by 2006 for federal contests, affecting jurisdictions where 18% of voters still used cards in 2004. No substantive commercial resurgence has materialized, rendering punched cards irrelevant outside minor archival or experimental niches.[32][33]Physical Design and Production

Card Materials and Dimensions

Punched cards were manufactured from smooth, sturdy cardstock to provide the necessary rigidity for mechanical handling while maintaining flexibility for punching and transport. The standard thickness of 0.007 inches (0.18 mm) ensured consistent stacking density, with approximately 143 cards per inch, facilitating reliable feeding in tabulators and sorters without jamming or misalignment.[34][35] The IBM 80-column card established the dominant dimensions of 7 3/8 inches wide by 3 1/4 inches high (187.325 mm × 82.55 mm), selected to match the size of early 20th-century U.S. dollar bills for compatibility with existing paper-handling infrastructure.[34][5] This format balanced data capacity with machinability, using rectangular holes measuring approximately 0.125 inches in length positioned across 12 rows and 80 columns to prevent overlap and tearing during high-speed processing.[36] Variations addressed density trade-offs; for instance, the IBM 96-column card employed smaller rectangular holes and tighter spacing for increased information storage per card, while maintaining comparable overall dimensions to leverage existing equipment.[37] In contrast, Remington Rand's 90-column format utilized round holes of about 0.069 inches in diameter across two sets of 45 columns, with cards sharing similar width and height but optimized for their proprietary round-hole readers to enhance sensing reliability.[38][39] Material and dimensional choices prioritized cost-effective production from abundant cardstock alongside durability against wear in automated systems, where thin profiles reduced transport friction yet withstood repeated passes through punches and verifiers.[34]Manufacturing Processes and Quality Control

The production of punched cards relied on specialized high-speed rotary presses developed by IBM engineer Fred M. Carroll, which integrated printing, cutting, and stacking processes to manufacture card stock efficiently.[1] By 1937, IBM deployed 32 such presses at its Endicott, New York facility, outputting 5 to 10 million cards daily, enabling large-scale supply for data processing applications.[1] These automated systems marked a shift from manual methods, substantially lowering per-unit costs through increased throughput and reduced labor. Punching operations distinguished between bulk replication and individualized data entry. Gang punches facilitated the simultaneous perforation of multiple cards using a master template, ideal for duplicating repetitive datasets across decks.[40] In contrast, keypunch machines, such as the IBM 029, enabled operators to punch variable information column-by-column via keyboard input, printing human-readable data alongside holes for verification. Quality assurance emphasized data integrity and physical durability. Verification typically involved duplicate punching, where cards were re-keyed on a separate pass or machine like the IBM 514 Reproducing Punch, halting operations upon detecting discrepancies between original and copy holes.[41] [42] Manufacturing inspections focused on uniform hole placement and card flatness to prevent misreads, with automated presses minimizing defects in stock preparation.[1] Over time, these processes supported IBM's output of billions of cards, sustaining industry dominance through reliable, scalable production.[1]Data Representation Standards

Hole Configurations and Encoding Schemes

Punched cards encoded data through the presence or absence of rectangular holes arranged in a grid of typically 12 horizontal rows and up to 80 vertical columns, with each column dedicated to representing a single character or digit.[43] This configuration stemmed from the need for reliable mechanical and electrical detection, where a hole's presence causally enabled a sensing mechanism—such as a pin or electrical brush—to register a signal, while its absence blocked it, directly mapping to binary states without intermediary abstraction.[44] Early designs prioritized numeric data for statistical applications, using 10 rows labeled 0 through 9, where a single hole in one row per column denoted the corresponding decimal digit; this decimal-direct approach minimized punching errors in manual entry and facilitated human verification against source documents.[1] To accommodate alphanumeric characters, two additional zone rows (typically rows 11 and 12) were incorporated, allowing combinations of a zone punch and a digit punch to represent letters and symbols via a binary-coded decimal (BCD) scheme.[43] In BCD encoding, the zone rows provided higher-order bits (e.g., row 12 for one zone, row 11 for another), combined with the digit rows for lower bits, yielding up to 12 possible single punches or valid combinations per column while avoiding ambiguous multi-punch interpretations in most systems.[45] This evolution from pure decimal to BCD balanced compatibility with emerging binary electronic machines—preserving decimal accuracy to prevent rounding errors in financial and census computations—while the fixed 80-column width limited storage to 80 characters per card, a constraint driven by card stock stability and punch machine precision.[44] Zone punches also enabled sign indication in numeric fields through overpunching: a digit hole combined with row 12 for positive or row 11 for negative, supporting arithmetic operations without dedicated columns.[45] Binary bit-per-hole encoding, using multiple holes across rows in a column to represent sequential bits, appeared in specialized control or low-density applications but was rarer for primary data due to increased error susceptibility in keypunching and reduced density compared to character-oriented schemes.[43] These configurations ensured deterministic mapping, with empirical reliability verified through tabulation machine outputs matching punched inputs in large-scale tests, such as census validations where misreads triggered mechanical jams or electrical faults.[1]Rectangular-Hole Formats (Hollerith and IBM Variants)

The rectangular-hole punched card format originated with Herman Hollerith's designs, which evolved under IBM into the industry-standard 80-column card introduced in 1928. This format replaced earlier round-hole systems, enabling denser data storage through smaller, rectangular perforations arranged in 12 rows across 80 columns. Each column supported up to 12 possible punch positions, with the bottom nine rows dedicated to numeric digits 0-9 and the top three rows (zones 11, 12, 0) used for alphabetic and special characters via combinations like zone punches with numeric.[1][46] The card dimensions standardized at 7 3/8 inches wide by 3 1/4 inches high, constructed from 0.007-inch-thick card stock to ensure durability during mechanical handling.[34] IBM refined the format in 1930 by expanding from 10 to 12 rows, facilitating extended binary-coded decimal (EBCDIC precursor) encoding for alphanumeric data. This 80-column layout dominated U.S. data processing for decades, supporting applications from census tabulation to early computing input, with rectangular holes measuring approximately 1/8 inch wide by 3/16 inch tall to minimize jamming in readers while maximizing capacity. Variants included stub cards, half-height versions limited to 40 columns, designed for integration with ledger sheets or forms to reduce material waste and enable detachable data records.[1][47] In 1969, IBM introduced the 96-column rectangular-hole card alongside the System/3 minicomputer, featuring a reduced height of 2 5/8 inches but matching width, with three tiers of 32 columns each supporting six punch positions (BA8421 code) for 6-bit BCD encoding and increased density without altering handling equipment significantly. The Port-A-Punch system, debuted in the late 1950s, utilized pre-scored half-cards (typically 40 columns) punched manually via a handheld stylus device, allowing field personnel to edit or enter data on-site before integration into full 80-column decks, thus streamlining workflows in remote or low-volume scenarios.[37][48][49] These IBM variants contrasted with European standards, such as the German 80- or 90-column formats often using round holes or different row arrangements, but the U.S. rectangular designs achieved near-universal adoption in Western data processing due to IBM's market dominance and compatibility with tabulating machinery.[5][50]Round-Hole Formats (Powers and Remington Rand)

Powers developed round-hole punched cards in the early 1900s as an alternative to rectangular-hole designs, enabling entry into tabulation markets by avoiding patent conflicts on hole shape. These cards used circular perforations to store data, with initial configurations supporting up to 45 columns for statistical processing in applications like the U.S. Census. Remington Rand, after acquiring the Powers Accounting Machine Company in 1927, introduced 90-column round-hole cards around 1930 to support alphameric data encoding and bypass limitations on column counts. The round holes, typically punched via mechanical devices that processed the full card at once, allowed for pre-release error verification, reducing waste compared to column-by-column keypunching. [38] [24] These formats claimed operational benefits, including cleaner cuts from round punches that minimized chad debris and lowered jamming risks in readers due to smoother edges and uniform geometry. Round holes adapted sensing mechanisms differently, facilitating reliable electrical contact via brushes or consistent optical detection without the directional tearing risks of rectangles. [51] The 90-column round-hole standard integrated with Remington Rand's UNIVAC computers in the 1950s, serving military and government data processing needs where its encoding density proved suitable for complex records. Despite innovations, adoption remained limited to a minority share of installations, reflecting entrenched preferences for competing formats in commercial sectors. [5]Specialized and Proprietary Formats

Mark-sense cards utilized specially coated stock permitting pencil markings in designated zones, which optical readers detected via conductivity changes or reflectance differences rather than punched holes. Introduced in the 1950s for applications such as standardized testing and surveys, these formats enabled simplified data entry without mechanical punching, with early IBM readers sensing the electrical conductivity of graphite pencil traces on carbon-impregnated paper.[52] Aperture cards integrated a die-cut window into standard card stock to affix microfilm inserts, primarily for archiving engineering drawings and technical diagrams, while peripheral punched holes encoded metadata like drawing numbers for automated retrieval. Measuring approximately 7.5 by 3.25 inches, these cards appeared in both plain and Hollerith-punched variants, the latter allowing machine sorting and cataloging of the embedded visual records.[53][54] Powers-Samas equipment relied on round-hole punching in 40- or 21-column layouts, detected mechanically via falling pins in rotary or linear readers, diverging from IBM's rectangular electrical sensing and fostering proprietary ecosystems with limited cross-vendor compatibility. This design necessitated custom punches and interpreters, as the hole geometry and column spacing precluded interchange with dominant rectangular formats, compelling users to maintain dedicated hardware lineages.[55] Such specialized variants, including diagonal or slanted punching in certain Powers implementations for optimized rotary feed alignment, underscored the era's fragmented standards, where proprietary innovations prioritized mechanical reliability over universality, often binding organizations to single suppliers for end-to-end processing.[55]Terminology and Classification

Key Terms for Holes, Positions, and Cards

In punched card systems, the chad denotes the small disk or fragment of paper or cardstock excised by the punching process, originally treated as a collective noun akin to chaff before referring to individual pieces.[56] A hanging chad specifically describes a chad incompletely detached, often clinging by one or more corners, which could interfere with mechanical reading in tabulators or, notably, lead to ambiguous vote tabulation in punched card ballots as seen in the 2000 U.S. presidential election.[56][57] The column constitutes a vertical alignment of potential punch positions on the card, with the dominant IBM format employing 80 columns numbered sequentially from 1 (leftmost) to 80 (rightmost), each encoding a single character via hole combinations.[43][1] Within each column, rows—also termed punch positions—form horizontal levels for holes, standardized in 12-row IBM cards as upper zone rows (labeled 12, 11, and 0 from top) for alphabetic or special encoding and lower digit rows (1 through 9) for numeric values.[58][45] Punching methods distinguish gang punching, which replicates identical hole patterns across multiple cards simultaneously for efficiency in duplicating fixed data fields, as exemplified by the IBM Type 501 Automatic Numbering Gang Punch introduced in 1926, from unit punching, which involves entering data hole-by-hole or card-by-card individually via manual keypunch devices.[59] Such terminology clarifies operational distinctions in historical records, where "punch" serves dually as a verb (to perforate the card) or noun (the resulting hole), averting ambiguity in descriptions of data entry or machinery.[60]Variations in Industry Naming Conventions

In the data processing industry, punched cards were commonly referred to as "tab cards" or "tabulating cards," particularly in contexts emphasizing their role in mechanical tabulation systems, as seen in mid-20th-century documentation for IBM and Remington Rand equipment.[61] This terminology highlighted the cards' function in sorting and aggregating data via tabulators, distinguishing them from broader "punch card" usage that encompassed programming and control applications.[62] Hollerith's original designs, foundational to IBM's systems, were explicitly termed "punched cards" in early U.S. Census applications from 1890 onward, a generic label that persisted but often carried vendor-specific connotations.[63] Competing manufacturers like the Powers Accounting Machine Company (later acquired by Remington Rand) employed round-hole formats and occasionally differentiated their media through operational terms tied to keypunch entry, though standardized nomenclature remained elusive without direct equivalents to IBM's "Hollerith card." Rectangular-hole cards dominated U.S. industry under IBM influence, fostering "punch card" as the default term by the 1930s, while round-hole variants were less generically labeled, contributing to fragmented training materials and documentation silos. These semantic divergences reinforced vendor lock-in, as proprietary glossaries in service manuals—such as IBM's emphasis on "card punch" versus Powers' machine-specific references—complicated cross-system adaptation and increased operational friction in mixed environments. Internationally, British systems introduced "chadless" perforated cards and tapes by the mid-20th century to mitigate debris issues in high-volume tabulation, contrasting with U.S. standards where chad-producing punches were normative and terms like "punch card" implied rectangular-hole defaults.[50] This led to divergent glossaries, with UK documentation favoring precision in perforation types over U.S.-centric "tab card" brevity. Efforts at unification, such as the American National Standards Institute's 1969 Hollerith Punched Card Code (ANSI X3.11-1969), codified 128-character encodings across 12-row cards but retained "Hollerith" nomenclature, acknowledging IBM's paradigm while aiming to reduce interoperability barriers from prior naming inconsistencies.[63] Such standards mitigated some lock-in effects, yet empirical records show persistent vendor-biased terminology in training until magnetic media supplanted cards in the 1970s–1980s. From a mechanical perspective, "punch card" evoked the physical perforation process suited to electrical sensing, whereas "tab card" underscored batch tabulation efficiency, influencing how industries documented workflows—e.g., IBM manuals prioritizing punch verification for electrical readers over purely mechanical sorters.[64] These distinctions had causal downstream effects, including higher error rates in cross-vendor setups due to mismatched terminologies in operator guides, as evidenced by pre-ANSI complaints in data processing literature about "incompatible card dialects."[61]Operational Mechanics

Punching and Data Entry Methods

Keypunch machines, resembling typewriters with keyboards mapped to punch positions, enabled operators to enter data by striking keys that drove needles to perforate holes in specific columns and rows of cards according to predefined encoding schemes.[65] These devices processed cards column by column, advancing automatically after each set of punches, with later models incorporating programmable features for field skipping and data duplication to streamline repetitive entries.[41] Skilled operators typically achieved punching rates of 200 to 300 cards per hour, depending on data complexity and machine model, though early manual pantograph punches were slower at 100 to 200 cards per hour.[65] [66] This manual process represented a significant bottleneck in data preparation workflows, as human input speed limited overall system throughput prior to automated alternatives.[67] Verification occurred via dedicated verifier machines, where operators re-keyed data from source documents; mismatches triggered mechanical stops for correction, ensuring accuracy without repunching.[41] Interpreters attached to keypunches printed human-readable text alongside punches for visual cross-checks against originals.[41] For duplication and backups, reproducing punches automatically transferred data from master cards to blank ones at speeds up to 100 to 130 cards per minute, often rearranging fields or adding summaries.[68] [69] Gang punching extended this by using a master card to simultaneously punch identical data into trailing detail cards, facilitating efficient replication of common record headers or constants.[69]Reading and Interpretation Technologies

Punched cards were read primarily through electrical sensing, where the absence of card material at a punched hole enabled completion of an electrical circuit to detect data. In Herman Hollerith's 1890 tabulating machine, spring-loaded pins passed through holes to dip into mercury cups beneath the card, closing circuits that advanced counters or dials for each detected hole.[16] This mercury-contact method allowed manual or semi-automatic reading of stationary cards, with each circuit pulse incrementing mechanical registers for tabulation.[4] Subsequent advancements shifted to dynamic reading of cards in motion, using metal brushes positioned above a conductive roller or bar beneath the card path. As the card advanced, brushes swept across columns; a hole permitted brush contact with the roller, generating an electrical pulse to signal the hole's presence, while intact card stock insulated non-punched positions.[70] This brush-over-roller design, refined by IBM in models like the 557 introduced in 1954, supported reliable high-volume processing by minimizing mechanical wear and enabling precise timing via synchronous card feeds. Sorters and tabulators leveraged these mechanisms for rapid interpretation, with multiple brushes reading all 80 columns in IBM formats nearly simultaneously. The IBM 83 sorter, for example, achieved 1,000 cards per minute by isolating one column per pass via a single adjustable sensing brush, directing cards to output pockets based on detected holes.[71] Tabulators extended this with full-card reading, using plugboard wiring to route pulses for customized summations, printing, or card selection, processing at comparable or slightly reduced speeds depending on output complexity.[72] Optical reading played a supplementary role, initially through mark-sensing brushes for pencil-filled ovals on cards lacking full punches, and later for verifying punched data via light transmission through holes. By the 1970s, dedicated optical readers handled up to 2,000 cards per minute, though primarily for hybrid or marked formats rather than pure hole detection.[73] Fundamentally, hole detection rested on the punch creating a conductive pathway, transforming mechanical absence into an electrical signal for interpretation.Error Detection and Validation Procedures