Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

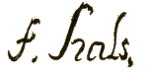

Frans Hals

View on Wikipedia

Frans Hals the Elder (UK: /hæls/,[1] US: /hɑːls, hælz, hɑːlz/;[2][3][4] Dutch: [frɑns ˈɦɑls]; c. 1582 – 26 August 1666) was a Dutch Golden Age painter. He lived and worked in Haarlem, a city in which the local authority of the day frowned on religious painting in places of worship but citizens liked to decorate their homes with works of art.[5] Hals was highly sought after by wealthy burgher commissioners of individual, married-couple,[6] family, and institutional-group portraits.[7][8] He also painted tronies for the general market.[9]

Key Information

There were two quite distinct schools of portraiture in 17th-century Haarlem: the neat (represented, for example, by Verspronck); and a looser, more painterly style at which Frans Hals excelled. Some of Hals's portrait work is characterised by a subdued palette, reflecting the politely serious tones of his fashionable clients' wardrobe. In contrast, the personalities he paints are full of life, typically with a friendly glint in the eye or the glimmer of a smile on the lips.

Hals was born at Antwerp in the southern Spanish Netherlands, but because of the chaos wrought there by the Spanish at that time, his family moved to Haarlem when he was little. Many of his Haarlem clients were also émigrés from the South.

Biography

[edit]Hals was born in 1582 or 1583 in Antwerp, then in the Spanish Netherlands, as the son of cloth merchant Franchois Fransz Hals van Mechelen (c. 1542–1610) and his second wife Adriaentje van Geertenryck.[10] Like many, Hals's parents fled during[11] the Fall of Antwerp (1584–1585) from the south to Haarlem in the new Dutch Republic in the north, where he lived for the remainder of his life. Hals studied under Flemish émigré Karel van Mander,[10][12] whose Mannerist influence, however, is barely noticeable in Hals's work.

In 1610, Hals became a member of the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke, and he started to earn money as an art restorer for the town council. He worked on their large art collection, which Karel van Mander had described in his Schilderboeck ("Painter's Book") published in Haarlem in 1604. The most notable works were those of Geertgen tot Sint Jans, Jan van Scorel, and Jan Mostaert that hung in the St John's Church in Haarlem. The restoration work was paid for by the council. The council had confiscated all Catholic religious art in the Haarlemse Noon, although it did not formally possess the entire collection until 1625, when the city fathers had decided which were suitable for the town hall. The remaining art, which was considered too Roman Catholic, was sold to Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, a fellow guild member, on condition that he remove it from Haarlem. It was in this cultural context that Hals began his career in portraiture, since the market had disappeared for religious themes.

The earliest known example of Hals's art is the portrait of Jacobus Zaffius (1611). His 'breakthrough' came with the life-sized group portrait The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616. His most famous sitter was René Descartes, whom he painted in 1649.

Frans Hals married his first wife Anneke Harmensdochter around 1610. Frans was of Catholic birth, however, so their marriage was recorded in the city hall and not in church.[13] Unfortunately, the exact date is unknown because the older marriage records of the Haarlem city hall before 1688 have not been preserved.[13] Anneke was born 2 January 1590 as the daughter of bleacher Harmen Dircksz and Pietertje Claesdr Ghijblant, and her maternal grandfather, linen producer Claes Ghijblant of Spaarne 42, bequeathed the couple the grave in the Grote Kerk church where both are buried, though Frans took over 40 years to join his first wife there.[13] Anneke died in 1615, shortly after the birth of their third child and, of the three, Harmen survived infancy and one had died before Hals's second marriage.[13]

As biographer Seymour Slive has pointed out, older stories of Hals abusing his first wife were confused with another Haarlem resident of the same name. Indeed, at the time of these charges, the artist had no wife to mistreat, as Anneke had died in May 1615.[14] Similarly, historical accounts of Hals's propensity for drink were largely based on embellished anecdotes of his early biographers like Arnold Houbraken; there is no direct evidence that Hals did drink heavily. After his first wife died, Hals took on the young daughter of a fishmonger to look after his children and, in 1617, he married Lysbeth Reyniers. They married in Spaarndam, a small village outside the banns of Haarlem, because she was already eight months pregnant. Hals was a devoted father, and they went on to have eight children.[15]

Contemporaries such as Rembrandt moved their households according to the caprices of their patrons, but Hals remained in Haarlem and insisted that his customers come to him. According to the Haarlem archives, a schutterstuk that Hals started in Amsterdam was finished by Pieter Codde because Hals refused to paint in Amsterdam, insisting that the militiamen come to Haarlem to sit for their portraits. For this reason, we can be sure that all sitters were either from Haarlem or were visiting Haarlem when they had their portraits made.

Hals's work was in demand through much of his life, but he lived so long that he eventually went out of style as a painter and experienced financial difficulties. In addition to his painting, he worked as a restorer, art dealer, and art tax expert for the city councilors. His creditors took him to court several times, and he sold his belongings to settle his debt with a baker in 1652. The inventory of the property seized mentions only three mattresses and bolsters, an armoire, a table, and five pictures[16] (these were by himself, his sons, van Mander, and Maarten van Heemskerck).[17] Left destitute, he was given an annuity of 200 florins in 1664 by the municipality.[16]

The Dutch nation fought for independence during the Eighty Years' War,[16] and Hals was a member of the local schutterij, a military guild. He included a self-portrait in his 1639 painting of the St Joris company, according to its 19th-century painting frame. (It has not been possible to confirm this.) It was not common for ordinary members to be painted, as that privilege was reserved for the officers. Hals painted the company three times. He was also a member of a local chamber of rhetoric, and in 1644 he became chairman of the Guild of St Luke.

Frans Hals died in Haarlem in 1666 and was buried in the Grote Kerk church.[18] He had been receiving a city pension, which was highly unusual and a sign of the esteem with which he was regarded. After his death, his widow applied for aid and was admitted to the local almshouse, where she later died.

Artistic career

[edit]

Hals is best known for his portraits, mainly of wealthy citizens such as Pieter van den Broecke and Isaac Massa, whom he painted three times. He also painted large group portraits for local civic guards and for the regents of local hospitals. He was a Dutch Golden Age painter who practiced an intimate realism with a radically free approach. His pictures illustrate the various strata of society: banquets or meetings of officers, guildsmen,[16] local councilmen from mayors to clerks, itinerant players and singers, gentlemen, fishwives, and tavern heroes. In his group portraits, such as The Banquet of the Officers of the St Adrian Militia Company in 1627, Hals captures each character in a different manner. The faces are not idealized and are clearly distinguishable, with their personalities revealed in a variety of poses and facial expressions.

Hals was fond of daylight and silvery sheen, while Rembrandt used golden glow effects based upon artificial contrasts of low light in immeasurable gloom. Hals seized a moment in the life of his subjects with rare intuition. What nature displayed in that moment he reproduced thoroughly in a delicate scale of color and with mastery over every form of expression. He became so clever that exact tone, light and shade, and modeling were obtained with a few marked and fluid strokes of the brush.[16] He became a popular portrait painter and painted the wealthy of Haarlem on special occasions. He won many commissions for wedding portraits (the husband is traditionally situated on the left, and the wife situated on the right). His double portrait of the newly married Olycans hang side by side in the Mauritshuis, but many of his wedding portrait pairs have since been split up and are rarely seen together.

Wedding portraits

[edit]-

Portrait of Jacob Pietersz Olycan (1596–1638), 1625, Mauritshuis.

-

Portrait of Aletta Hanemans (1606–1653), bride of Jacob Olycan, 1625, Mauritshuis.

-

Paulus van Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre.

-

Catharina Both van der Eem, bride of Paulus Beresteyn, 1629, Louvre.

-

Dorothea Berck (1593–1684), wife of Joseph Coymans, 1644, Private Collection.

-

Isabella Coymans, wife of Stephan Geraedts, 1652, Private Collection.

The only record of his work in the first decade of his independent activity is an engraving by Jan van de Velde copied from the lost portrait of The Minister Johannes Bogardus. Early works by Hals show him as a careful draughtsman capable of great finish yet spirited, such as Two singing boys with a lute and a music book and Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia (1616). The flesh that he painted is pastose and burnished, less clear than it subsequently became. Later, he became more effective, displayed more freedom of hand and a greater command of effect.[16]

During this period, he painted the full-length portrait of Madame van Beresteyn (Louvre) and a full-length portrait of Willem van Heythuysen posing with a sword. Both these pictures are equalled by the other Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia (with different portraits) and the same militia in 1627 and Banquet of the Officers of the St Hadrian Militia of 1633. A similar painting with the date of 1639 suggests some study of Rembrandt masterpieces, and a similar influence is apparent in a group portrait of 1641 representing the regents of the St Elisabeth Gasthuis and in his 1639 portrait of Maria Voogt at Amsterdam.[16]

From 1620 till 1640, he painted many double portraits of married couples on separate panels, the man on the left panel and his wife on the right panel. Only once did Hals portray a couple on a single canvas: Couple in a garden: Wedding portrait of Isaac Abrahamsz. Massa and Beatrix van der Laan, (c. 1622, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam).[20][21]

His style changed throughout his life. Paintings of vivid color were gradually replaced by pieces where mostly black came to dominate. This was probably due to the sober dress of his Protestant sitters, more than any personal preference. One simple way to observe this change is to look at all of the portraits that he painted through the years with his trademark pose leaning over the back of a chair:

-

1626

-

1631

-

1633

-

1635

-

1645

-

1645

-

1655

-

1665

Portrait painter

[edit]

Later in his life, his brush strokes became looser, fine detail becoming less important than the overall impression.[22] His earlier pieces radiated gaiety and liveliness, while his later portraits emphasized the stature and dignity of the people portrayed. This austerity is displayed in Regents of the St Elizabeth Hospital in 1641 and,[23] two decades later, The Regents and Regentesses of the Old Men's Almshouse (c. 1664), which are masterpieces of color, though in substance all but monochromes.[24][25] His restricted palette is particularly noticeable in his flesh tints, which became greyer from year to year, until finally the shadows were painted in almost absolute black, as in the Tymane Oosdorp.[16]

This tendency coincides with the period when Hals gained fewer commissions from the wealthy, and some historians have suggested that a reason for his predilection for black and white pigment was the low price of these colors as compared with the costly lakes and carmines.[16] Both conclusions are probably correct, however, because Hals did not travel to his sitters, unlike his contemporaries, but let them come to him. This was good for business because he was exceptionally quick and efficient in his own well-fitted studio, but it was bad for business when Haarlem fell on hard times.

As a portrait painter, Hals had scarcely the psychological insight of a Rembrandt or Velázquez, though in a few works, like the Admiral de Ruyter, the Jacob Olycan, and the Albert van der Meer paintings, he reveals a searching analysis of character which has little in common with the instantaneous expression of his character portraits. In these, he generally sets upon the canvas the fleeting aspect of the various stages of merriment, from the subtle, half ironic smile that quivers round the lips of the curiously misnamed Laughing Cavalier to the grin of the Malle Babbe.[26][27] To this group of pictures belong the Lute Player, the Gypsy Girl and the Laughing Fisherboy, whilst the Marriage Portrait of Isaac Massa and Beatrix van der Laen and the somewhat confused group of the Beresteyn Family at the Louvre show a similar tendency. Far less scattered in arrangement than this Beresteyn group, and in every respect one of the most masterly of Hals's achievements is the group called The Painter and his Family, which was almost unknown until it appeared at the winter exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1906.[16]

According to the Frans Hals catalogue raisonné, 1974, 222 known paintings can be ascribed to Hals. This list was compiled by Seymour Slive in 1970−1974 who also wrote an exhibition catalogue in 1989 and produced an update to his catalogue raisonné work in 2014. In 1989, another authority on Hals, Claus Grimm,[28] disagreed with Slive and published a shorter œuvre of 145 paintings in his Frans Hals. Das Gesamtwerk.

It is not known whether Hals ever painted landscapes, still lifes or narrative pieces, but it is unlikely. His debut for Haarlem society in 1616 with his large group portrait for the St George militia shows all three disciplines, but if that painting was his signboard for future commissions, it seems he was subsequently only hired for portraits. Many artists in the 17th century in Holland opted to specialise, and Hals also appears to have been a pure portrait specialist.

Painting technique

[edit]

Hals was a master of a technique that utilized something previously seen as a flaw in painting, the visible brushstroke. The soft curling lines of Hals's brush are always clear upon the surface: "materially just lying there, flat, while conjuring substance and space in the eye."[29] In this way his style was similar to Édouard Manet; in fact, Hals was described by author Raymond Cogniat as "the Manet of his day."[30] Lively and exciting, the technique can appear "ostensibly slapdash"[29] – people often think that Hals 'threw' his works 'in one toss' (aus einem Guss) onto the canvas. This impression is not correct.[31] Hals did occasionally paint without underdrawings or underpainting (alla prima), but most of the works were created in successive layers, as was customary at that time. Sometimes a drawing was made with chalk or paint on top of a grey or pink undercoat, and was then more or less filled in, in stages. It does seem that Hals usually applied his underpainting very loosely: he was a virtuoso from the beginning. This applies, of course, particularly to his genre works and his somewhat later, mature works. Hals displayed tremendous daring, great courage and virtuosity, and had a great capacity to pull back his hands from the canvas, or panel, at the moment of the most telling statement. He didn't 'paint them to death', as many of his contemporaries did, in their great accuracy and diligence whether requested by their clients or not.

In the 17th century his first biographer, Schrevelius wrote: "An unusual manner of painting, all his own, surpassing almost everyone," on Hals's painting methods. For that matter, schematic painting was not Hals's own idea (the approach already existed in 16th century Italy), and Hals was probably inspired by Flemish contemporaries, Rubens and Van Dyck, in his painting method. Haarlem resident Theodorus Schrevelius was struck by the vitality of Hals's portraits which reflected 'such power and life' that the painter 'seems to challenge nature with his brush'.

Influence

[edit]

Frans influenced his brother Dirck Hals (born at Haarlem, 1591–1656), who was also a painter.[32] Additionally, five of his sons became painters:

- Harmen Hals (1611–1669)

- Frans Hals the Younger (1618–1669)

- Jan Hals (1620–1654)

- Reynier Hals (1627–1672)

- Nicolaes Hals (1628–1686)

Though most of his sons became portrait painters, some of them took up still-life painting or architectural studies and landscapes. Still lifes formerly attributed to his son Frans II have since been re-attributed to other painters, however.[10][33] Hals painted a young woman reaching into a basket in a still life market scene by Claes van Heussen.[34]

Other contemporary painters who took inspiration from Hals were,[35] with the main cities they were based in:

- Jan Miense Molenaer (1609–1668), Haarlem and Amsterdam

- Judith Leyster (wife of Molenaer, 1609–1660), Haarlem and Amsterdam

- Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685), Haarlem

- Adriaen Brouwer (1605–1638), mostly Antwerp

- Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck (1597–1662), Haarlem

- Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670), Amsterdam

- Cornelis de Bie (1621–1664), Amsterdam

Hals had a large workshop in Haarlem and many students, though 19th century biographers questioned some of his pupils, since their painting styles were so dissimilar to Hals. In his De Groote Schouburgh (1718–21), Arnold Houbraken mentions Philips Wouwerman, Adriaen Brouwer, Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten, Adriaen van Ostade and Dirck van Delen as students. Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne was also a student, according to his diary with notes left by his son Laurens Vincentsz van der Vinne.[36] Roestraten was not only a student (the Haarlem archives contain a notarised document, which supports this fact), but he also became a son-in-law of Hals when he married his daughter Adriaentje. The Haarlem portrait painter, Johannes Verspronck, one of about 10 competing portraitists in Haarlem at the time, possibly studied for some time with Hals.

In terms of style, the closest to Hals's work is the handful of paintings that are ascribed to Judith Leyster, which she often signed. She also 'qualifies' as a possible student, as does her husband, the painter Jan Miense Molenaer.

In the 19th century, his technique influenced the work of impressionists and realists including Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, Charles-François Daubigny, Max Liebermann, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Gustave Courbet, and in the Netherlands, Jacobus van Looy and Isaac Israëls. Lovis Corinth named Hals as his biggest influence.[37]

The Post-Impressionist artist Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: 'What a joy it is to see a Frans Hals, how different it is from the paintings – so many of them – where everything is carefully smoothed out in the same manner.' Hals chose not to give a smooth finish to his painting, as most of his contemporaries did, but mimicked the vitality of his subject by using smears, lines, spots, large patches of color and hardly any details.

Legacy

[edit]

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica has an article on Frans Hals by Paul George Konody, who observes: Hals's reputation waned after his death and for two centuries he was held in such poor esteem that some of his paintings, which are now among the proudest possessions of public galleries, were sold at auction for a few pounds or even shillings. The portrait of Johannes Acronius realized five shillings at the Enschede sale in 1786. The Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen at the Alte Pinakothek sold in 1800 for £4: 5s[16] (£4.25 in decimal notation).

Nevertheless, Hals's art did not go altogether unappreciated in the time between his death in 1666 and the 1860s. In his Groote Schouburgh (1718–1721), Arnold Houbraken recorded Hals's life and praised his style, adding that the figures in one of the large group portraits: ... zoo kragtig en natuurlyk geschildert zyn, dat zy de aanschouwers schynen te willen aanspreken ("... are painted so powerfully and naturally, they seem to want to talk to us").[38] Dutch artists known to have admired Hals enough to make copies of his paintings include Cornelis van Noorde (1731–1795) and Wybrand Hendricks (1744–1831). Empress Catherine the Great (reigned 1762–1796) acquired ten Hals works for her collection. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) visited the Alte Pinakothek to copy Hals's work, and Hals's influence is apparent in Fragonard's portraits de fantaisie. Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) made study sketches after Hals. At the Royal Academy in London, Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) lectured on Hals in 1774, praising his handling of faces and the consequent remarkable individuality of his portraits. Reynolds was less enthusiastic about Hals's characteristic loose finish, which he thought betrayed impatience. Subsequently, in 1781 Reynolds visited the Hals collection then at Haarlem Town Hall (now at the Frans Hals Museum) and soon after bought two Hals works. Reynolds's biographer James Northcote (1736–1831), who was a fellow portraitist, remarked that Hals could have caught a bird in flight, grasping it, as it were, from life – something he said Titian would not have been capable of.[39]

Starting at the middle of the 1860s his prestige rose again thanks to the efforts of critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger.[40][41] With his rehabilitation in public esteem came the enormous rise in value, and, at the Secretan sale in 1889, the portrait of Pieter van den Broecke was bid up to 4,420 francs, while in 1908 the National Gallery paid £25,000 for the large family group from the collection of Lord Talbot de Malahide.[16]

Hals's work remains admired, particularly with young painters who can find many lessons about practical technique from his unconcealed brushstrokes.[29] Hals's works have found their way to countless cities all over the world and into museum collections. From the late 19th century, they were collected everywhere—from Antwerp to Toronto, and from London to New York. Many of his paintings were then sold to American collectors.

Several of his most important works are owned by the town council of Haarlem. They are now at the Frans Hals Museum in the Groot Heiligland, Haarlem.[42] Before 1913 they hung in the Town Hall, where Impressionists went to see them.

The Hals crater on Mercury is named in his honour.[43]

Hals was pictured on the Netherlands' 10-guilder banknote of 1968.[44]

The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616 appears on the restaurant wall in the 1989 Peter Greenaway film The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover.[45]

-

Catharina Hooft with her Nurse, c. 1619–1620

-

Three Children with a Goat Cart, c. 1620

-

Portrait of a Man, 1630

-

Jacobus Zaffius, 1611

-

Married Couple in a Garden, 1622

-

Peeckelhaeringh, c. 1628–1630

-

The Mulatto, 1627

-

Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull, c. 1615

-

Portrait of a Woman, 1644

-

The Merry Drinker, c. 1628–1630

-

St Matthew, c. 1625

-

The Rommel Pot Player, c. 1618–1622

-

Daniel van Aken

-

Portrait of René Descartes, c. 1649

-

Portrait of a Man (about 1665), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (66.1054)

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Public collections (selection)

[edit]- Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem

- Frick Collection, New York City

- Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen

- Louvre, Paris

- Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam[48]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston[49]

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.[50]

- Kenwood House

- Wallace Collection, London

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hals, Frans". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022.

- ^ "Hals". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ "Hals". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ "Hals" Archived 12 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Grijzenhout, Frans (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "The Religion(s) of Frans Hals", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 14–30, doi:10.2307/jj.22135982.5, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ den Tonkelaar, Emilie (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "From a Parisian Dining Room to a German Private Museum: Frans Hals in the Collections of Count André Mniszech and Marcus Kappel", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 194–210, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ van Roon, Marike (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Painted Stitches: Embroidery and the Paintings of Frans Hals", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 49–64, doi:10.2307/jj.22135982.7, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ te Marvelde, Mireille; Abraham, Liesbeth; van Putten, Herman; Franken, Michiel (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "A Box Full of Research: Early Twentieth-Century Documentation on the Scientific Investigation and Restoration of the Eight Group Portraits by Frans Hals", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 110–129, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Atkins, Christopher D.M. (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Peeckelhaering and the Performance of Race", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 31–48, doi:10.2307/jj.22135982.6, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ a b c Frans Hals iat the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ^ Liedtke, Walter (August 2011). "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and P. Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 379.

- ^ a b c d Anneke Harmensdr Archived 14 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine in Nieuwe gegevens betreffende Anneke Harmansdr., de eerste echtegonte van Frans Hals, by M. Thierry de Bye Dolleman working from research by C.A. de Goederen-van Hees, pp. 249-257, Haerlem: jaarboek 1973, ISSN 0927-0728, on the website of the North Holland Archives

- ^ Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and Pieter Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 376.

- ^ See Hals biography Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine in the Web Gallery of Art

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hals, Frans". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Slive, Seymour, Frans Hals, and P. Biesboer (1989). Frans Hals. Munich: Prestel. p. 406.

- ^ "Artist Info". www.nga.gov. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Biesboer, Pieter (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Willem or Balthasar? The Portrait of a Member of the Coymans Family by Frans Hals Reconsidered", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 82–91, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ 'Review of: Frans Hals portraits: A family reunion', Oud Holland Reviews, December 2020. Archived 22 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Review of exhibition publication.

- ^ Atkins, Christopher DM. (2012). The Signature Style of Frans Hals Painting, Subjectivity, and the Market in Early Modernity. Amsterdam University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9789048514595. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Rikken, Marrigje (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Foreword", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 7–8, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ van Putten, Herman; Abraham, Liesbeth; te Marvelde, Mireille (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Lost Lines: New Light on the Painting Technique of Frans Hals", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 171–182, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Abraham, Liesbeth; Levy-van Halm, Koos (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "More than Decoration: The Map in Frans Hals's Regents of St Elisabeth's Hospital", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 65–81, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Abraham, Liesbeth (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Unfinished Business? Comparing Hals's Late Regents and Regentesses", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 183–192, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Tummers, Anna; Wallert, Arie; Erdmann, Robert G.; Kleinert, Katja; Hartwieg, Babette; Mahon, Dorothy; Centeno, Silvia; Groves, Roger; Anisimov, Andrei (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "The New York Malle Babbe: Original, Studio Work, or Forgery?", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 130–154, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Franken, Michiel (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "'Because you simply cannot argue about art with a chemist': Scientific Research on Frans Hals's Paintings in the Netherlands during the 1920s", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 211–220, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Grimm, Claus (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Looking at Frans Hals in the Digital Age: The Benefits of Detailed Comparisons", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 155–170, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ a b c Schjeldahl, Peter (8 August 2011). "Haarlem Shuffle: The Fast World of Frans Hals". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. pp. 74–75. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2011.(subscription required)

- ^ Cogniat, Raymond (1964). Seventeenth Century Painting. New York: The Viking Press. p. 26.

- ^ "Frans Hals Biography | Life, Paintings, Influence on Art | frans-hals.org". www.frans-hals.org. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Konody, Paul George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 865–867, see page 867, last para.

Quite in another form, and with much of the freedom of the elder Hals, Dirk Hals, his brother (born at Haarlem, died 1656), is a painter of festivals and ball-rooms...

- ^ Konody, Paul George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 865–867, see page 867, last but one para.

Of the master's numerous family none has left a name except Frans Hals the Younger, born about 1622, who died in 1669. His pictures represent cottages and poultry...

- ^ Young woman with a display of fruit and vegetables Archived 14 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine in the RKD

- ^ "Malerei: Frans Hals Ausstellung – Der Maler des lachenden Menschen - WELT". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Middelkoop, Norbert E. (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Frans Hals's Portraits of Painters: A Reconnaissance", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 92–108, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Lovis Corinth A Feast of Painting, p17, Prestel, Vienna, 2009 ISBN 978-3-901508-64-6. ISBN 978-3-7913-4378-5

- ^ Houbraken, Arnold (1718). "Frans Hals" section in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen [The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters and Paintresses] (in Dutch). Published by Arnold Houbraken himself. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Erftenmeijer, Antoon (2014). Het fenomeen Frans Hals. Haarlem: Frans Hals Museum. pp. 148–150. ISBN 97-894-6208-167-3. There is also an English edition: ISBN 978-9462081680, titled Frans Hals: A Phenomenon.

- ^ Johnson, Paul. Art: A New History, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003, p. 369

- ^ Bezold, John (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Frans Hals Connoisseurs and Exhibitions: From Thoré to Today", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 221–243, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ Middelkoop, Norbert E. (2024), Middelkoop, Norbert E.; Ekkart, Rudi E.O. (eds.), "Frans Hals: A Survey of Current Research", Frans Hals, Iconography – Technique – Reputation, Amsterdam University Press, pp. 9–12, ISBN 978-90-485-6606-8, retrieved 1 January 2025

- ^ "Hals". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2012). 2013 Standard Catalog of World Paper Money. Krause Publications. p. 713. ISBN 978-1440229565. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Travers, Peter (6 April 1990). "The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover". RollingStone. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Hals' Singing Boy with Flute". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Hals's Malle Babbe". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen". Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Portrait of a Man". collections.mfa.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Collection Rijksmuseum". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- (in Dutch) Frans Hals biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- Seymour Slive: Frans Hals, 3 Volumes (oeuvre catalogue), New York / London 1970–1974

- Frans Hals (exhibition catalogue Washington/London/Haarlem, 1989.

- Claus Grimm published his Frans Hals. Das Gesamtwerk in 1989 (Stuttgart/Zürich; also translated into Dutch and English).

- N. Middelkoop and A. van Grevenstein, Frans Hals. Leven, werk, restauratie (Life, work and restorations) (Haarlem Amsterdam 1988). This work gives an account of restorations of the riflemen's pieces, but it also gives a picture of Hals's life and work.

- Antoon Erftemeijer (2004): Frans Hals in het Frans Hals Museum, Amsterdam/Gent (in Dutch, English and French), in which various chapters are devoted to Hals's life, his predecessors, portrait painting in the Golden Age, Hals's painting technique and other subjects. Many pictures with close-ups in this book show Hals's works in great detail.

- Christopher D. M. Atkins (2003): "Frans Hals's Virtuoso Brushwork", Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, pp. 281–309). Parts of this article are excerpts of The Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, July 2005 by Antoon Erftemeijer, Frans Hals Museum curator.

- Christopher D. M. Atkins (2012): The Signature Style of Frans Hals: Painting, Subjectivity, and the Market in Early Modernity, Amsterdam University Press.

- Henry R. Lew (2018): Imaging the World, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, Australia Chapter 9: Frans Hals, pages 108–126.

- Steven Nadler (2022): The Portraitist: Frans Hals and His World, The University of Chicago Press.

- Lelia Packer and Ashok Roy (2022): Frans Hals: The Male Portrait, The Wallace Collection.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Frans Hals at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Frans Hals at Wikimedia Commons

- 27 artworks by or after Frans Hals at the Art UK site

- Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem

- Frans Hals Works, Biography and Style

- The National Gallery

- The Wallace Collection

- Web Gallery of Art (large collection of pictures and extensive biography)

- Frans Hals at zeno.org (in German)

- Olga's Gallery

- Works and literature on Frans Hals

- Frans Hals in the Metropolitan Museum 2011 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Walter Liedtke, "Frans Hals: Style and Substance" (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011)

Frans Hals

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early Life

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp around 1582 or 1583, the eldest son of Franchois Fransz Hals, a cloth dresser originally from Mechelen, and his second wife, Adriana van Geertenryck from Antwerp.[2][5] The family, like many others, fled the Spanish siege and capture of Antwerp in 1585 during the Eighty Years' War, relocating to Haarlem in the Dutch Republic by the late 1580s, where they settled permanently.[2][6] Hals spent his childhood and early adolescence in Haarlem, a burgeoning artistic center that had attracted numerous Flemish refugees, including painters and craftsmen, fostering an environment rich with influences from southern Netherlandish traditions.[1] Although direct evidence of his earliest artistic pursuits is limited, his family's Antwerp origins likely provided indirect exposure to Flemish art through personal connections and the local Haarlem community of émigrés.[7] Around 1600–1603, Hals apprenticed under the Flemish Mannerist painter and art theorist Karel van Mander I (1548–1606), who had established a studio and academy in Haarlem after fleeing the south himself.[1][6] Under van Mander's guidance, Hals studied Mannerist techniques, including stylized figures and history painting principles drawn from classical and Italian sources.[1] By 1610, Hals had advanced sufficiently to register as a master painter in the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, signifying the formal beginning of his independent professional career.[1][7]Family and Personal Life

Frans Hals married his first wife, Anneke Harmensdochter Abeels, around 1610; she died in 1615 shortly after giving birth to their third child, leaving him with two surviving sons from the union.[8] In 1617, Hals wed Lysbeth Reyniers, the daughter of a Haarlem fishmonger, who was pregnant at the time of their marriage; the couple went on to have eight more children, for a total of ten offspring across both marriages, five of whom—sons Harmen, Frans II, Reynier, Nicolaes, and Jan—survived to adulthood and pursued careers as painters.[9] Despite his professional success, Hals's large family contributed to ongoing financial strains, with court records documenting debts and lawsuits beginning in 1616, including claims from a children's caregiver and frequent arrears to local tradespeople.[10] By 1654, he owed a baker 200 guilders and settled the debt by surrendering household items and five paintings, while in his final years, the Haarlem city council provided assistance and exempted him from guild dues.[9] Hals's religious beliefs remain somewhat ambiguous, though recent scholarship indicates he leaned toward Protestantism in the predominantly Reformed context of Haarlem, as evidenced by the Protestant baptisms of his children and his limited output of religious-themed works. Earlier assumptions of Catholic sympathies, stemming from his Antwerp origins and first marriage to a Catholic woman, have been reevaluated, with no firm evidence of ongoing Catholic practice despite the tolerant but Protestant-dominated environment.[11] His involvement in the local community included membership in the Saint George civic guard from 1612 to 1624, where he socialized with burghers who later commissioned his portraits, reflecting the interconnectedness of his personal and professional spheres in Haarlem society.[1] Personal challenges persisted into mid-life, such as a 1654 debt-related lawsuit that highlighted his precarious finances, and family tragedies including the death of his son Reynier in 1672, six years after Hals's own passing; Reynier, a painter like his father, succumbed in Amsterdam at age 45.[12] These difficulties did not sever Hals's ties to civic institutions, which occasionally provided support and patronage, underscoring the mutual reliance between the artist and his Haarlem community.[9]Later Years and Death

In the 1650s and 1660s, Frans Hals experienced deepening poverty amid declining commissions, exacerbated by economic challenges in Haarlem and his advancing age, which limited his productivity.[13][9] Despite his earlier renown, Hals faced ongoing debts, including a 200-guilder arrears to a baker in 1654 that led to the seizure of his modest household goods—comprising only three mattresses, bolsters, a table, an armoire, and five paintings—highlighting his financial vulnerability.[14] By 1661, due to his frailty and impoverishment, the Haarlem Guild of Saint Luke exempted him from its annual dues of six stuivers.[9] Recognizing his contributions and dire circumstances, the Haarlem authorities provided civic support starting in September 1662, granting Hals an annual pension of 200 guilders, along with assistance for rent and firewood, which exceeded standard poor relief and reflected esteem for the aging artist as "impotent" from health issues and old age.[15] This aid continued, and in 1664, at approximately age 82, Hals received an additional civic allowance of three cartloads of peat for fuel, underscoring his reliance on municipal charity for basic needs.[14] Hals's output diminished but persisted into his final years, with his last known works being the group portraits of the Regents and Regentesses of the Old Men's Almshouse in Haarlem, completed around 1664 and showcasing his enduring mastery despite physical decline.[1][9] He died on August 26, 1666, in Haarlem at about age 83 or 84, and was buried on September 1 in the choir of St. Bavo's Church (Grote Kerk), in the family grave of his first wife's grandfather—a site of relative honor rather than obscurity.[16][14][15] Following his death, Hals's estate was settled with minimal assets, as noted in the 1666 inventory, which listed few possessions and reflected his lifelong frugality and hardships; his widow, Lysbeth Reyniers, later received ongoing weekly support of 14 stuivers (equivalent to 36 guilders annually) starting in 1675.[15][9]Artistic Career

Early Works and Influences

Frans Hals's earliest independent paintings from the 1610s reveal a young artist grappling with Mannerist conventions while beginning to infuse his compositions with greater vitality. His first signed and dated major work, The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Militia Company (1616), depicts a group of civic guard officers in a lively gathering, arranged in a diagonal composition that echoes the elongated poses and contrived groupings typical of Mannerism. This painting, executed for the St. George Civic Guard in Haarlem, demonstrates the influence of his training under Karel van Mander, whose teachings emphasized classical proportions and rhetorical gestures derived from Flemish Mannerist traditions.[17][3] Hals's emerging style was shaped by a blend of Flemish and local Haarlem influences, encountered during his formative years and travels. The dynamic figures and robust forms in his early works reflect exposure to Peter Paul Rubens's Baroque energy, particularly after Hals's likely visit to Antwerp around 1616, where he would have seen Rubens's altarpieces and sketches emphasizing movement and light. In Haarlem, landscapists such as Esaias van de Velde influenced the tonal subtlety and atmospheric depth in Hals's backgrounds, grounding his portraits in the everyday Haarlem environment.[18][3][19] Thematically, Hals's early output focused on banquets and merry companies, capturing the convivial spirit of Dutch social life with hints of his developing loose brushwork. In pieces like The Merry Drinker (c. 1620–1630), a boisterous figure raises a glass in toast, rendered with fluid strokes that suggest texture and motion, foreshadowing his mature technique. Similarly, Peeckelharing (1623–1624), portraying a jester clutching a pickled herring as a symbol of folly, employs exaggerated expression and informal pose to evoke humor and immediacy. By the late 1610s, Hals had evolved from the stiff, idealized figures of his initial efforts to more natural, lively expressions, as seen in the varied interactions among the officers in his 1616 banquet scene, marking a pivotal shift toward realism and spontaneity.[20][17]Rise to Prominence

In the early 1610s, Frans Hals achieved his first notable success with the Portrait of Jacobus Hendricksz Zaffius (1611), depicting the Catholic provost and archdeacon of Haarlem's St. Bavo chapter at a time when the city was predominantly Reformed, showcasing Hals' ability to secure commissions from influential ecclesiastical figures despite religious tensions.[13] This work marked the beginning of his reputation for capturing dignified yet approachable likenesses, leading to expanded patronage in the 1620s from merchants and clergy seeking individual and family portraits to affirm their status in Haarlem's burgeoning Protestant society. For instance, he painted the Portrait of Pieter Cornelisz van der Morsch (1616), a civic guard member and brewer whose family ties reflected the rising merchant class, and soon after received commissions like the double portrait of merchant Isaac Massa and his wife Beatrix van der Laen (1622), emphasizing intimate domestic scenes that highlighted familial bonds and economic prosperity.[21][15] By the mid-1620s, Hals solidified his position as Haarlem's preeminent portraitist through high-profile works such as Portrait of a Man (The Laughing Cavalier) (1624), which exemplified his innovative approach to conveying vitality and personality, attracting further elite clients including clergy like the poet and minister Samuel Ampzing, whose portrait (1628) praised Hals' skill in rendering intellectual gravitas. Despite a setback in 1633, when a militia commission for the Meagre Company was reassigned to Pieter Codde after a dispute with the patrons, Hals quickly regained favor with regents and other civic leaders, securing subsequent group and individual portraits that underscored his versatility and appeal to Haarlem's governing circles.[22] His active involvement in the Guild of St. Luke, where he had enrolled in 1610, further bolstered his standing, culminating in leadership roles that positioned him as a central figure in the local art community by the 1640s.[9] Hals' ascent was contemporaneously recognized for the lively dynamism of his portraits, with art theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten lauding his loose brushwork in Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (1678) as a masterful means to infuse figures with motion and life, distinguishing him from more rigid contemporaries.[23] Similarly, Haarlem schoolmaster Theodorus Schrevelius acclaimed Hals in 1648 as excelling in portraying "the movements of the mind" through expressive features, cementing his reputation as the city's foremost interpreter of human character during the Dutch Golden Age's peak.[9]Civic Guard Portraits

Frans Hals received commissions for six group portraits of Haarlem's civic guard companies between 1616 and 1639, primarily for the St. George Militia and the St. Adrian (Calivermen) Civic Guard, which were displayed in their respective doelen (headquarters).[24] These paintings commemorated the officers' three-year terms of service, often depicting farewell banquets or meetings, and featured prominent local citizens from wealthy brewing and textile families who served in honorary, unpaid roles.[25] Following the Twelve Years' Truce of 1609–1621, the militias' active military functions diminished after 1618, transforming them into ceremonial organizations focused on social gatherings and civic pride, which influenced the shift toward lively, banquet-themed compositions in Hals's works.[26] Among the key commissions, Hals's first major civic guard portrait was The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Militia Company in 1616, an oil-on-canvas measuring 175 × 324 cm that depicts eleven officers in a dynamic gathering around a table laden with food and drink.[27] This was followed by The Banquet of the Officers of the St. Adrian Civic Guard (c. 1627), portraying the company's leaders in a lively assembly, and culminated in his largest such work, The Banquet of the Officers of the St. George Militia Company in 1639, a monumental 218 × 421 cm canvas showing sixteen figures in two rows amid banners and weapons.[9] These paintings not only secured Hals's reputation in Haarlem but also captured the guards' sashes in company colors—white and orange for St. George, blue for St. Adrian—to denote rank and affiliation.[25] Hals addressed the compositional challenge of arranging 10 to 16 figures in group portraits by employing diagonal lines, varied poses, and interactive gestures to create vitality and avoid the rigid, row-like stiffness characteristic of earlier works by rivals such as Cornelis van Haarlem, whose 1599 St. George portrait had presented officers in isolated, Mannerist profiles.[27] In the 1639 painting, for instance, Hals positioned himself as a self-portrait in the upper left, integrating the viewer into the scene while balancing hierarchical elements like pikes and halberds.[28] Recent technical analysis, including macro-XRF scanning, has revealed Hals's layering process in this work: initial chalk and carbon sketches on canvas, followed by phased underpainting in earth tones, working-up with fluid color applications, and finishing highlights using lead white and vermilion, often with workshop assistance for backgrounds but personal execution of faces.[29] These insights, drawn from 2024 studies by conservators including Mireille te Marvelde, confirm the paintings' original indigo and verdigris pigments, some of which faded over time, underscoring Hals's innovative direct painting technique for lifelike ensembles.[30]Later Commissions

In the 1640s and 1650s, Frans Hals shifted his focus from civic guard portraits to more institutional commissions, particularly those for almshouses and regent groups in Haarlem, reflecting the changing patronage landscape of the Dutch Golden Age.[1] By the 1660s, at the advanced age of over 80, he received his final major commissions for the Old Men's Almshouse (Oude Mannenhuis), painting two companion group portraits: Regents of the Old Men's Almshouse and Regentesses of the Old Men's Almshouse, both completed in 1664. These works depict the administrators of the charitable institution with a somber, introspective quality, emphasizing their roles in overseeing care for the elderly poor.[31] Hals's later output diminished considerably due to his advancing age, which limited his ability to undertake large-scale projects, leading him to produce more intimate and empathetic portraits of elderly subjects that conveyed quiet dignity amid hardship.[1] Notable among these is Portrait of a Man in a Slouch Hat (c. 1660–1666), an oil-on-canvas depiction of an unidentified sitter characterized by loose brushwork and a contemplative gaze, now housed in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Kassel.[32] The 1664 regent portraits mark Hals's last dated works, after which no further commissions are recorded, signaling the end of his active career. This reduction in productivity—from over 200 authenticated paintings before 1640 to fewer than 50 afterward—was exacerbated by an economic downturn in Haarlem during the mid-17th century, driven by the decline of the textile industry, wartime disruptions, and an oversaturated art market that diminished patronage for portraitists.[1][33] Additionally, increased competition from pupils of Rembrandt, such as those active in nearby Amsterdam who adopted more dramatic lighting and psychological depth, further eroded Hals's traditional Haarlem clientele.[1] These pressures culminated in personal financial poverty, prompting Haarlem's municipality to grant him a modest pension in 1664 to support his basic needs.[34]Style and Technique

Portraiture Approach

Frans Hals's approach to portraiture emphasized capturing the fleeting expressions and inherent personality of his subjects, prioritizing naturalism and individuality over idealized or formal representations prevalent in earlier traditions. Unlike the polished and stately formality of Anthony van Dyck's works, which often elevated sitters through refined poses and smooth finishes, Hals sought to convey a sense of immediacy and vitality, portraying individuals with relaxed gestures and engaging facial nuances that suggested friendliness, reserve, or preoccupation without revealing deeper introspection.[1][3][35] This philosophy reflected a departure from the stiff conventions of Dutch portraiture, allowing Hals to infuse his paintings with a lively intimacy that highlighted the sitter's unique character within the bounds of social decorum.[1] Hals's subject range encompassed a broad cross-section of Haarlem society, including prosperous merchants, clergy, families, and even members of the lower classes such as fisher folk and musicians, demonstrating his versatility in commissioned and open-market works. He frequently employed direct gazes to foster a personal connection between sitter and viewer, embedding narrative context through subtle environmental cues that underscored the subject's role or status.[1][3][35] Compositionally, Hals favored asymmetrical arrangements to create dynamic tension and visual interest, integrating symbolic props like books, maps, or everyday objects to enrich the portrayal and provide contextual depth without overwhelming the figure.[3][35] In the Calvinist society of the Dutch Golden Age, Hals's portraits served as potent status symbols, commissioned by Haarlem's affluent burghers to affirm their social standing and virtues amid the city's economic boom driven by industries like brewing and textiles. His works mirrored this prosperity by depicting subjects in attire and settings that conveyed restraint and honesty, aligning with Protestant ideals of modesty while subtly celebrating civic pride and personal achievement.[1][3][35] A key element of Hals's methodology was the alla prima technique, involving direct, wet-on-wet application of paint in single sittings to achieve spontaneity and a sense of captured movement, as opposed to laboriously layered finishes. This approach, executed with bold yet controlled brushwork, produced the illusion of life and energy that contemporaries admired; for instance, Haarlem scholar Theodorus Schrevelius in 1648 praised Hals's ability to infuse portraits with such "power and life" that they seemed to challenge nature itself.[3][35][36]Brushwork and Composition

Frans Hals's brushwork is renowned for its loose, visible strokes that create texture and vitality, marking a departure from the smoother finishes of earlier Dutch painters like those in the Mannerist tradition. He employed broad, unblended daubs of color for clothing and backgrounds to suggest movement and light, while using finer, more controlled strokes for facial features to capture subtle expressions. This technique evolved significantly: in his early works around 1610–1620, Hals applied tighter, more opaque layers, particularly in faces and garments, but by the late 1620s, his approach shifted to fluid, thinly brushed applications that allowed underlying tones to influence the final surface, enhancing a sense of immediacy. Recent technical studies, including those published in 2024, have confirmed these methods through advanced analyses like X-radiography and pigment examination, further elucidating his direct painting process and workshop practices.[37][38] In composition, Hals favored dynamic poses that imply motion and interaction, often twisting figures slightly to engage the viewer and break from static symmetry. He modeled forms primarily through light and color contrasts rather than heavy chiaroscuro shading, using broad highlights to define volume and depth without laborious blending. This approach is evident in portraits where sitters appear caught in mid-gesture, contributing to the lively, three-dimensional quality of his scenes.[37] Technical studies reveal Hals's use of preparatory materials that supported his efficient workflow, including lead-white grounds often mixed with earth pigments to create a sand-colored base, over which he applied thin glazes for tonal modulation in shadows and mid-tones. Specific techniques included impasto for luminous highlights on fabrics and skin, adding tactile emphasis, and dry brushing to render intricate details like hair and lace with a feathery, translucent effect. These methods, confirmed through X-radiography and cross-sectional analysis, underscore his direct painting process from a monochrome underdrawing.[39] Hals's innovations in brushwork broke from the polished surfaces of predecessors like Karel van Mander, embracing a "rough" manner that prioritized expressive freedom, as seen in the Laughing Cavalier (1624), where loose strokes on the embroidered sleeve and cuff convey opulence through implied texture rather than meticulous rendering. This style prefigured later developments in loose painting, influencing perceptions of spontaneity in portraiture.[37]Innovations in Genre Painting

Frans Hals made significant contributions to Dutch genre painting during the early decades of the seventeenth century, particularly through his depictions of merry companies and peasant scenes that captured the vibrancy of everyday Haarlem life. Unlike the more moralizing or static genre works of his contemporaries, Hals infused these scenes with humor, music, and social commentary, portraying figures in moments of unrestrained joy and interaction. His limited output of pure genre pieces—fewer than twenty—primarily dates to before 1640, after which he shifted focus to portraiture, but these works nonetheless demonstrated his ability to blend portrait-like vitality with broader narrative elements.[34][40] A prime example is The Merry Drinker (c. 1628–1630, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), where a boisterous figure raises a glass in toast, pipe in hand, surrounded by subtle still-life elements like the pewter jug that add texture and realism to the scene. This tronie, or character study, exemplifies Hals' innovation in elevating anonymous types to expressive individuals, using exaggerated gestures and open-mouthed laughter to convey a sense of captured spontaneity and communal revelry. Similarly, Malle Babbe (c. 1633, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) portrays a laughing madwoman with an owl on her shoulder, incorporating prophetic or symbolic elements—the owl evoking folly or nocturnal wisdom—that comment on the margins of society, blending peasant genre with allegorical undertones.[40][41] Hals adapted techniques from the Utrecht Caravaggisti, such as dramatic lighting and realistic figure modeling, but lightened their tenebrism into a brighter, more jovial tone suited to Dutch burgher culture, avoiding heavy moral contrasts in favor of comedic exuberance. His rapid, loose brushwork—bold dashes for clothing and faces—created an impression of immediacy, as if the moments were fleeting and alive, influencing the perception of genre as dynamic rather than posed. This approach not only highlighted social commentary on Haarlem's taverns and festivities but also bridged genre and portraiture, allowing everyday vitality to permeate his compositions.[40][41][34]Notable Works

Individual Portraits

Frans Hals specialized in individual portraits that captured the essence of his sitters with remarkable vivacity and psychological insight, often depicting merchants, civic officers, and local notables from Haarlem's burgeoning middle class.[42] These works typically ranged from bust-length to half-length formats, allowing for intimate focus on facial expressions and attire that conveyed social status and personality.[1] Over the course of his career, Hals produced more than 220 paintings in total, the majority being individual portraits, with scholars identifying over 100 such works and at least 30 as autograph pieces bearing his signature or clear stylistic hallmarks.[43][44] In the 1620s, Hals's individual portraits often exuded youthful vigor and exuberance, reflecting the optimism of Haarlem's prosperous merchant community. A prime example is The Laughing Cavalier (1624, oil on canvas, 83 x 67 cm, Wallace Collection, London), which portrays an unidentified young man aged about 26 in a flamboyant slashed doublet embroidered with gold and silver threads, his left hand resting confidently on his hip.[45] The sitter's engaging smile—achieved through subtle modeling of the mouth corners and a direct gaze—conveys a sense of bold self-assurance rather than outright laughter, a technique that revolutionized Dutch portraiture by infusing formality with lively character.[46] Similarly, Singing Boy with Flute (c. 1623–1625, oil on canvas, 68.8 x 55.2 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) captures a youthful figure in mid-performance, his flushed cheeks and wild white feather in a feathered cap emphasizing playful energy through fluid brushstrokes and vibrant mauve and blue tones.[47] These early pieces highlight Hals's ability to blend portrait-like realism with genre elements, portraying patrons or imagined types with infectious vitality. By the mid-1620s, Hals began introducing greater introspective depth in his individual portraits, shifting toward more contemplative expressions while maintaining his signature loose technique. In Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen (1625, oil on canvas, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), the wealthy Haarlem cloth merchant is shown half-length, seated with a sword at his side and gloved hand extended in a gesture of poised elegance, his gaze conveying quiet confidence and reserve.[48] This work, one of two depictions of the sitter (the other a full-length version from 1634 in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen), exemplifies Hals's evolution toward nuanced psychological portrayal, where the subject's introspective demeanor contrasts with the earlier exuberance of his 1620s youth-focused commissions.[49] Attribution debates surrounding Hals's individual portraits persist, particularly regarding studio versions and workshop contributions. In 2024, scholars remained divided on the authenticity of several works once attributed to Hals, with curators like Friso Lammertse advocating for a core of 48 undisputed masterpieces from a total corpus of around 220 paintings, while others, following Claus Grimm's rigorous analysis, question up to 80 attributions based on stylistic inconsistencies and technical evidence.[50] For instance, studio replicas of iconic portraits like The Laughing Cavalier have sparked ongoing discussions about Hals's collaborative practices, underscoring the challenges in distinguishing his hand from that of assistants in an era of prolific output for Haarlem's elite patrons.[44]Group Portraits

Frans Hals produced approximately 20 group portraits throughout his career, a body of work that revolutionized Dutch civic art by infusing multi-figure compositions with dynamic energy and individual characterization.[1] These paintings extended beyond the well-known civic guard commissions to include intimate family groups and institutional regents, showcasing Hals's ability to balance collective identity with personal distinctiveness. In family portraits, such as the early Family Group in a Landscape (c. 1620, Toledo Museum of Art), Hals captured domestic harmony through relaxed poses and natural interactions, setting a precedent for informal ensemble depictions in Dutch art.[51] Similarly, his late regents portraits for the Old Men's Almshouse in 1664 portrayed administrators with a poignant realism that highlighted their roles in charitable care. Hals's techniques in these works emphasized viewer engagement through varied eye directions, where figures gaze in multiple directions—some toward the viewer, others at companions or into space—creating a sense of lively conversation and spatial depth.[26] He achieved hierarchical yet egalitarian arrangements by positioning central figures slightly more prominently while ensuring all participants contributed equally to the composition's rhythm, as seen in the Officers of the St. Adrian Militia Company (1633, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), where sashes and gestures denote rank without diminishing camaraderie.[1] This approach addressed the inherent challenge of avoiding monotony in group settings, using diagonal lines, overlapping forms, and contrasting expressions to infuse static ensembles with movement and vitality.[52] The Pauper portraits for the Old Men's Almshouse (1662–1664), including the Regents of the Old Men's Almshouse and its female counterpart, demonstrate Hals's empathetic late style, rendering the elderly overseers with loose, expressive brushwork that conveys weariness and humanity rather than stiff formality.[31] These works, painted when Hals was in his eighties and facing his own financial hardships, evoke compassion for the institution's impoverished residents through subdued tones and introspective gazes.[53] A 2024 technical study of the 1633 Officers of the St. Adrian Militia, involving infrared reflectography and macro X-ray fluorescence, revealed extensive underdrawings in carbon-based materials beneath the figures, illustrating Hals's spontaneous planning process and adjustments to enhance compositional balance.[52] This restoration also addressed faded pigments like indigo, restoring the painting's original vibrancy and underscoring Hals's innovative handling of color and form in group dynamics.[29]Other Subjects

While Frans Hals is renowned for his portraiture, his non-portrait works constitute a small fraction of his oeuvre, comprising under 10% of his approximately 200 authenticated paintings and serving primarily as experimental forays into other genres rather than major commercial pursuits. These pieces demonstrate Hals's versatility and engagement with broader Dutch Golden Age trends, though they were less sought after than his lucrative portrait commissions.[50] Hals's contributions to genre painting and still life are exemplified by works like Malle Babbe (c. 1633), a tronie depicting a laughing madwoman or witch-like figure from Haarlem folklore, accompanied by an owl symbolizing folly or witchcraft, now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. This oil-on-canvas painting captures a momentary expression with Hals's characteristic loose brushwork, blending portrait-like intensity with genre narrative to evoke everyday eccentricity.[54] Similarly, The Rommelpot Player (c. 1618–1620), housed in the Kimbell Art Museum, portrays a street musician entertaining children with a traditional rommelpot instrument, emphasizing lively interaction and social observation in a compact, animated scene that highlights Hals's early interest in capturing transient joy.[55] These genre scenes reflect Hals's innovative approach to depicting lower-class life, though they remain outliers in his predominantly elite-focused career.[56] Religious and history paintings by Hals are exceedingly rare, constrained by the Protestant Reformation's restrictions in Haarlem, where public religious imagery was discouraged in favor of iconoclastic simplicity, limiting such works to private commissions. One notable early example is a lost or destroyed composition from around 1611 involving Christ and the Apostles, though few details survive; more documented are the four Evangelist portraits from c. 1625–1628, such as Saint John the Evangelist in the J. Paul Getty Museum, which blend devotional solemnity with Hals's dynamic style but were likely produced for personal or scholarly patrons rather than ecclesiastical use.[57] These sparse religious efforts underscore the era's theological shifts, with Hals adapting biblical subjects to subdued, introspective formats amid Haarlem's Calvinist environment. Attributed landscapes further illustrate Hals's exploratory breadth, often featuring Haarlem views influenced by contemporaries like Jan van Goyen, whose monochromatic tonalities and atmospheric realism shaped the Dutch landscape tradition in the 1620s. A debated example is Haarlem Mill (c. 1620s), tentatively linked to Hals for its loose, impressionistic handling of windmill and skyline elements, though its attribution remains contested due to possible workshop involvement or collaboration with specialists like Pieter Molijn. Recent 2024 scholarship, including the RKD's comprehensive catalogue raisonné by Claus Grimm, has questioned three such non-portrait attributions, including potential landscape integrations, emphasizing technical analysis that reveals inconsistencies in execution and underdrawing compared to Hals's autograph works.[50] Overall, these landscapes served as experimental backdrops, less central to Hals's practice than his foregrounded human subjects.Influence and Legacy

Impact on Contemporaries

Frans Hals exerted a significant influence on his contemporaries within the Haarlem art scene, where his innovative approach to portraiture and genre painting introduced greater liveliness and spontaneity, outshining the more rigid styles of predecessors like Pieter Pietersz. the Elder, whose formal compositions lacked the dynamic energy that Hals brought to depictions of civic guards and individual sitters.[58] This shift was evident in Hals' competition for commissions, where his ability to capture fleeting expressions and movement secured him prominence over earlier Haarlem painters, fostering a competitive environment that elevated the local school's standards.[3] Hals' impact extended to key collaborators and rivals, notably shaping the work of Judith Leyster, who, after exposure to his techniques around the 1620s, adopted his loose brushstrokes and emphasis on momentary vitality in her genre scenes and portraits, leading to frequent misattributions of her paintings to him.[59] Similarly, Salomon de Bray drew from Hals' naturalism in his portraits and architectural designs, blending it with classical influences to create more expressive figures, as seen in his family groups that echoed Hals' informal groupings.[19] In the Haarlem school, Hals mentored pupils such as Pieter Molijn, who likely trained under him and incorporated his fluid handling into landscape elements, and shared civic guard commissions with Adriaen van Ostade, whose genre paintings of peasants reflected Hals' realistic character studies and vigorous brushwork.[3][60] Beyond Haarlem, Hals' visits to Amsterdam for major commissions, such as the 1637 militia portrait, exposed him to and influenced the city's artists, including Ferdinand Bol, whose later portraits adopted a comparable looseness in rendering fabrics and expressions derived from Hals' dynamic style.[36] His reputation was praised by Cornelis de Bie in 1661, who lauded Hals as a masterful teacher whose works seemed to breathe life, underscoring his role in inspiring peers across the Dutch Republic.[36] The dynamics of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, where Hals joined in 1610 and later served as dean in 1644, facilitated this exchange by regulating commissions and workshops, encouraging emulation among members like Leyster and de Bray while promoting collaborative projects that amplified Hals' stylistic innovations.[3][31]Influence on Later Artists

Frans Hals' innovative loose brushwork and lively portraiture experienced a significant revival in the mid-19th century, beginning with the efforts of French collectors and critics who championed his works as precursors to modern painting techniques. Around 1868, the influential critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger published articles praising Hals' direct, alla prima approach, drawing attention to his previously undervalued canvases in Haarlem collections and sparking a broader European interest. This rediscovery was facilitated by 19th-century auctions, where Hals' paintings fetched increasing prices and entered prominent private collections, such as those of French connoisseurs who acquired works like Portrait of a Seated Man through sales in the 1860s and 1870s.[61][62] In Britain during the 18th and early 19th centuries, Hals' energetic handling of paint influenced portraitists seeking vitality beyond classical ideals. Thomas Gainsborough, known for his fluid landscapes and portraits, drew on Dutch precedents including Hals' rough manner to infuse his sitters with immediacy and natural pose, as seen in works like Mrs. Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1785), where loose strokes evoke texture and movement. Similarly, Joshua Reynolds, while favoring the Grand Manner, occasionally emulated Hals' bravura brushwork in less formal portraits, adapting it to capture fleeting expressions amid his Venetian-inspired polish. John Constable admired Hals's bold, unfinished effects in the 1820s, influencing his own experimental sketches.[63] The Impressionists of the 1870s revered Hals for his alla prima technique, which emphasized direct application of color to convey light and spontaneity. Édouard Manet, after visiting the Netherlands in 1872, explicitly praised Hals' method, incorporating its visible strokes into paintings like Le Bon Bock (1873), where the subject's relaxed demeanor and textured clothing echo Hals' informal vitality. Claude Monet echoed this admiration, citing Hals' loose handling as a model for capturing transient effects in works such as his Gare Saint-Lazare series, though Monet's focus remained on landscape over portraiture. Edgar Degas, a meticulous copier of masters, studied Hals' Laughing Cavalier (1624) in the Wallace Collection, replicating its confident gaze and embroidered details to refine his own ballet portraits with similar psychological directness.[64][65][66] Hals' legacy extended into the 20th century, shaping Expressionist and modernist approaches to form and emotion. Chaim Soutine, in his raw, distorted portraits of the 1920s, channeled Hals' expressive brushwork to heighten psychological intensity, as in The Pastry Chef (c. 1920–1921), where thick impasto and vivid color recall Hals' lively rendering of everyday figures. Pablo Picasso, during his neoclassical phase in the 1920s, adopted Hals-like looseness in portraits such as Woman with a Mantilla (1917), using abbreviated strokes for fabric and face to suggest volume without finish, blending it with his cubist fragmentation. This transmission persisted through engravings, like those by 19th-century etcher William Unger, which reproduced Hals' compositions for widespread study, and auctions that circulated originals among international collectors.[3][67][68]Modern Scholarship and Exhibitions