Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

In-camera effect

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

An in-camera effect is any visual effect in a film or video that is created solely by using techniques in and on the camera and/or its parts. The in-camera effect is defined by the fact that the effect exists on the original camera negative or video recording before it is sent to a lab or modified. Effects that modify the original negative at the lab, such as skip bleach or flashing, are not included. Some examples of in-camera effects include the following:

- Matte painting

- Schüfftan process

- Forced perspective

- Dolly zoom

- Lens flares

- Lighting effects

- Filtration such as using a fog filter to simulate fog, or a grad filter to simulate sunset.

- Shutter effects.

- Time-lapse, slow motion, fast motion, and speed ramping.

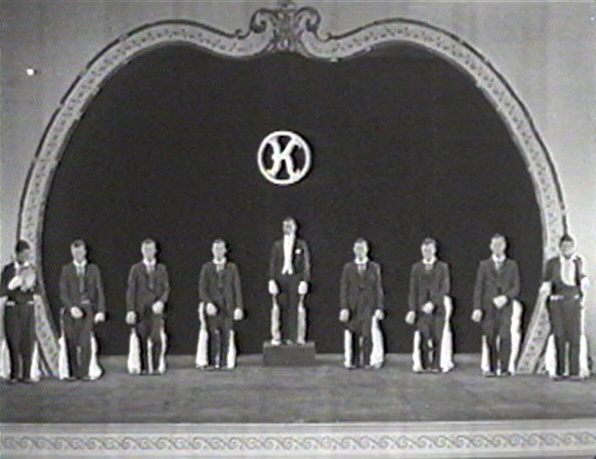

- Bipacks

- Slit-scan

- Infrared photography

- Reverse motion

- Front projection

- Rear projection

- Phonotrope a live animation technique that uses the frame-rate of a camera

There are many ways one could use the in-camera effect. The in-camera effect is something that often goes unnoticed but can play a critical part in a scene or plot. A popular example of this type of effect is seen in Star Trek, in which the camera is shaken to give the impression of motion happening on the scene. Another simple example could be using a wine glass to give the effect that "ghosting, flares, and refractions" from DIY photography.[1]