Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Time-lapse photography

View on Wikipedia

Time-lapse photography is a technique that causes the time of videos to appear to be moving faster than normal and thus lapsing. To achieve the effect, the frequency at which film frames are captured (the frame rate) is much lower than the frequency used to view the sequence. For example, an image of a scene may be captured at 1 frame per second but then played back at 30 frames per second; the result is an apparent 30 times speed increase.

Processes that would normally appear subtle and slow to the human eye, such as the motion of the sun and stars in the sky or the growth of a plant, become very pronounced. Time-lapse is the extreme version of the cinematography technique of undercranking. Stop motion animation is a comparable technique; a subject that does not actually move, such as a puppet, can repeatedly be moved manually by a small distance and photographed. Then, the photographs can be played back as a film at a speed that shows the subject appearing to move.

Conversely, film can be played at a much lower rate than at which it was captured, which slows down an otherwise fast action, as in slow motion or high-speed photography.

History

[edit]Some classic subjects of time-lapse photography include:

- Landscapes and celestial motion

- Plants and flowers growing

- Fruit rotting

- Evolution of a construction project

- People in the city

The technique has been used to photograph crowds, traffic, and even television. The effect of photographing a subject that changes imperceptibly slowly creates a smooth impression of motion. A subject that changes quickly is transformed into an onslaught of activity.

The inception of time-lapse photography occurred in 1872 when Leland Stanford hired Eadweard Muybridge to prove whether or not race horses hooves ever are simultaneously in the air when running. The experiments progressed for 6 years until 1878 when Muybridge set up a series of cameras for every few feet of a track which had tripwires the horses triggered as they ran. The photos taken from the multiple cameras were then compiled into a collection of images that recorded the horses running.[2]

The first use of time-lapse photography in a feature film was in Georges Méliès' motion picture Carrefour De L'Opera (1897).[3]

F. Percy Smith pioneered[4] the use of time-lapse in nature photography with his 1910 silent film The Birth of a Flower.[5]

Time-lapse photography of biological phenomena was pioneered by Jean Comandon in collaboration with Pathé Frères from 1909,[6][7] by F. Percy Smith in 1910 and Roman Vishniac from 1915 to 1918. Time-lapse photography was further pioneered in the 1920s via a series of feature films called Bergfilme (mountain films) by Arnold Fanck, including Das Wolkenphänomen in Maloja (1924) and The Holy Mountain (1926).

From 1929 to 1931, R. R. Rife astonished journalists with early demonstrations of high magnification time-lapse cine-micrography,[8][9] but no filmmaker can be credited for popularizing time-lapse techniques more than John Ott,[citation needed] whose life work is documented in the film Exploring the Spectrum.

Ott's initial "day-job" career was that of a banker, with time-lapse movie photography, mostly of plants, initially just a hobby. Starting in the 1930s, Ott bought and built more and more time-lapse equipment, eventually building a large greenhouse full of plants, cameras, and even self-built automated electric motion control systems for moving the cameras to follow the growth of plants as they developed. He time-lapsed his entire greenhouse of plants and cameras as they worked—a virtual symphony of time-lapse movement. His work was featured on a late 1950s episode of the request TV show You Asked for It.

Ott discovered that the movement of plants could be manipulated by varying the amount of water the plants were given, and varying the color temperature of the lights in the studio. Some colors caused the plants to flower, and other colors caused the plants to bear fruit. Ott discovered ways to change the sex of plants merely by varying the light source's color temperature. By using these techniques, Ott time-lapse animated plants "dancing" up and down synchronized to pre-recorded music tracks. His cinematography of flowers blooming in such classic documentaries as Walt Disney's Secrets of Life (1956), pioneered the modern use of time-lapse on film and television.[citation needed] Ott wrote several books on the history of his time-lapse adventures including My Ivory Cellar (1958) and Health and Light (1979), and produced the 1975 documentary film Exploring the Spectrum.

The Oxford Scientific Film Institute in Oxford, United Kingdom, specializes in time-lapse and slow-motion systems, and has developed camera systems that can go into (and move through) small places.[citation needed] Their footage has appeared in TV documentaries and movies.

PBS's NOVA series aired a full episode on time-lapse (and slow motion) photography and systems in 1981 titled Moving Still. Highlights of Oxford's work are slow-motion shots of a dog shaking water off himself, with close ups of drops knocking a bee off a flower, as well as a time-lapse sequence of the decay of a dead mouse.

The non-narrative feature film Koyaanisqatsi (1983) contained time-lapse images of clouds, crowds, and cities filmed by cinematographer Ron Fricke. Years later, Ron Fricke produced a solo project called Chronos shot using IMAX cameras. Fricke used the technique extensively in the documentary Baraka (1992) which he photographed on Todd-AO (70 mm) film.

Countless other films, commercials, TV shows and presentations have included time-lapse material. For example, Peter Greenaway's film A Zed & Two Noughts features a sub-plot involving time-lapse photography of decomposing animals and includes a composition called "Time Lapse" written for the film by Michael Nyman. In the late 1990s, Adam Zoghlin's time-lapse cinematography was featured in the CBS television series Early Edition, depicting the adventures of a character that receives tomorrow's newspaper today. David Attenborough's 1995 series The Private Life of Plants also utilised the technique extensively.

Terminology

[edit]The frame rate of time-lapse movie photography can be varied to virtually any degree, from a rate approaching a normal frame rate (between 24 and 30 frames per second) to only one frame a day, a week, or longer, depending on the subject.

The term time-lapse can also apply to how long the shutter of the camera is open during the exposure of each frame of film (or video), and has also been applied to the use of long-shutter openings used in still photography in some older photography circles. In movies, both kinds of time-lapse can be used together, depending on the sophistication of the camera system being used. A night shot of stars moving as the Earth rotates requires both forms. A long exposure of each frame is necessary to enable the dim light of the stars to register on the film. Lapses in time between frames provide the rapid movement when the film is viewed at normal speed.

As the frame rate of time-lapse photography approaches normal frame rates, these "mild" forms are sometimes referred to simply as fast motion or (in video) fast forward. This type of borderline time-lapse technique resembles a VCR in a fast forward ("scan") mode. A man riding a bicycle will display legs pumping furiously while he flashes through city streets at the speed of a racing car. Longer exposure rates for each frame can also produce blurs in the man's leg movements, heightening the illusion of speed.

Two examples of both techniques are the running sequence in Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989), in which a character outraces a speeding bullet, and Los Angeles animator Mike Jittlov's 1980s short and feature-length films, both titled The Wizard of Speed and Time. When used in motion pictures and on television, fast motion can serve one of several purposes. One popular usage is for comic effect. A slapstick comic scene might be played in fast motion with accompanying music. (This form of special effect was often used in silent film comedies in the early days of cinema.)

Another use of fast motion is to speed up slow segments of a TV program that would otherwise take up too much of the time allotted a TV show. This allows, for example, a slow scene in a house redecorating show of furniture being moved around (or replaced with other furniture) to be compressed in a smaller allotment of time while still allowing the viewer to see what took place.

The opposite of fast motion is slow motion. Cinematographers refer to fast motion as undercranking since it was originally achieved by cranking a handcranked camera slower than normal. Overcranking produces slow motion effects.

Methodology

[edit]Film is often projected at 24 frame/s, meaning 24 images appear on the screen every second. Under normal circumstances, a film camera will record images at 24 frame/s since the projection speed and the recording speed are the same.

Even if the film camera is set to record at a slower speed, it will still be projected at 24 frame/s. Thus the image on screen will appear to move faster.

The change in speed of the onscreen image can be calculated by dividing the projection speed by the camera speed.

So a film recorded at 12 frames per second will appear to move twice as fast. Shooting at camera speeds between 8 and 22 frames per second usually falls into the undercranked fast motion category, with images shot at slower speeds more closely falling into the realm of time-lapse, although these distinctions of terminology have not been entirely established in all movie production circles.

The same principles apply to video and other digital photography techniques. However, until very recently [when?], video cameras have not been capable of recording at variable frame rates.

Time-lapse can be achieved with some normal movie cameras by simply shooting individual frames manually. But greater accuracy in time-increments and consistency in exposure rates of successive frames are better achieved through a device that connects to the camera's shutter system (camera design permitting) called an intervalometer. The intervalometer regulates the motion of the camera according to a specific interval of time between frames. Today, many consumer grade digital cameras, including even some point-and-shoot cameras have hardware or software intervalometers available. Some intervalometers can be connected to motion control systems that move the camera on any number of axes as the time-lapse photography is achieved, creating tilts, pans, tracks, and trucking shots when the movie is played at normal frame rate. Ron Fricke is the primary developer of such systems, which can be seen in his short film Chronos (1985) and his feature films Baraka (1992, released to video in 2001) and Samsara (2011).

Short and long exposure

[edit]

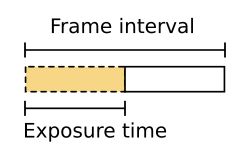

As mentioned above, in addition to modifying the speed of the camera, it is important to consider the relationship between the frame interval and the exposure time. This relationship controls the amount of motion blur present in each frame and is, in principle, exactly the same as adjusting the shutter angle on a movie camera. This is known as "dragging the shutter".

A film camera normally records images at 24 frames per second (fps). During each 1⁄24 second, the film is actually exposed to light for roughly half the time. The rest of the time, it is hidden behind the shutter. Thus exposure time for motion picture film is normally calculated to be 1⁄48 second (often rounded to 1⁄50 second). Adjusting the shutter angle on a film camera (if its design allows), can add or reduce the amount of motion blur by changing the amount of time that the film frame is actually exposed to light.

In time-lapse photography, the camera records images at a specific slow interval such as one frame every thirty seconds (1⁄30 fps). The shutter will be open for some portion of that time. In short exposure time-lapse the film is exposed to light for a normal exposure time over an abnormal frame interval. For example, the camera will be set up to expose a frame for 1⁄50 second every 30 seconds. Such a setup will create the effect of an extremely tight shutter angle giving the resulting film a stop-motion animation quality.

In long exposure time-lapse, the exposure time will approximate the effects of a normal shutter angle. Normally, this means the exposure time should be half of the frame interval. Thus a 30-second frame interval should be accompanied by a 15-second exposure time to simulate a normal shutter. The resulting film will appear smooth.

The exposure time can be calculated based on the desired shutter angle effect and the frame interval with the equation:

Long exposure time-lapse is less common because it is often difficult to properly expose film at such a long period, especially in daylight situations. A film frame that is exposed for 15 seconds will receive 750 times more light than its 1⁄50 second counterpart. (Thus it will be more than 9 stops over normal exposure.) A scientific grade neutral density filter can be used to compensate for the over-exposure.

Camera movement

[edit]Some of the most stunning time-lapse images are created by moving the camera during the shot. A time-lapse camera can be mounted to a moving car for example to create a notion of extreme speed.

However, to achieve the effect of a simple tracking shot, it is necessary to use motion control to move the camera. A motion control rig can be set to dolly or pan the camera at a glacially slow pace. When the image is projected it could appear that the camera is moving at a normal speed while the world around it is in time-lapse. This juxtaposition can greatly heighten the time-lapse illusion.

The speed that the camera must move to create a perceived normal camera motion can be calculated by inverting the time-lapse equation:

Baraka was one of the first films to use this effect to its extreme. Director and cinematographer Ron Fricke designed his own motion control equipment that utilized stepper motors to pan, tilt and dolly the camera.

The short film A Year Along the Abandoned Road shows a whole year passing by in Norway's Børfjord (in Hasvik Municipality) at 50,000 times the normal speed in just 12 minutes. The camera was moved, manually, slightly each day, and so the film gives the viewer the impression of seamlessly travelling around the fjord as the year goes along, each day compressed into a few seconds.

A panning time-lapse image can be easily and inexpensively achieved by using a widely available equatorial telescope mount with a right ascension motor.[10] Two axis pans can be achieved as well, with contemporary motorized telescope mounts.

A variation of these are rigs that move the camera during exposures of each frame of film, blurring the entire image. Under controlled conditions, usually with computers carefully making the movements during and between each frame, some exciting blurred artistic and visual effects can be achieved, especially when the camera is mounted on a tracking system that enables its own movement through space.

The most classic example of this is the "slit-scan" opening of the "stargate" sequence toward the end of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), created by Douglas Trumbull.

High-dynamic-range (HDR)

[edit]Time-lapse can be combined with techniques such as high-dynamic-range imaging. One method to achieve HDR involves bracketing for each frame. Three photographs are taken at separate exposure values (capturing the three in immediate succession) to produce a group of pictures for each frame representing the highlights, mid-tones, and shadows. The bracketed groups are consolidated into individual frames. Those frames are then sequenced into video.

Day-to-night transitions

[edit]Day-to-night transitions are among the most demanding scenes in time-lapse photography and the method used to deal with those transitions is commonly referred to as the "Holy Grail" technique.[11] In a remote area not affected by light pollution the night sky is about ten million times darker than the sky on a sunny day, which corresponds to 23 exposure values. In the analog age, blending techniques have been used in order to handle this difference: One shot has been taken in daytime and the other one in the night from exactly the same camera angle.

Digital photography provides many ways to handle day-to-night transitions, such as automatic exposure and ISO, bulb ramping and several software solutions to operate the camera from a computer or smartphone.[11]

See also

[edit]Related techniques

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ALMA Time-lapse Video Compilation Released". ESO Announcement. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Blog - From Ponies to ProjectCam: The History of Time Lapse Photography". Archived from the original on 2014-12-03.

- ^ Weston, Chris (2015-12-22). Spanning Time: The Essential Guide to Time-lapse Photography. CRC Press. ISBN 9781317907466.

- ^ McRobbie, Linda Rodriguez (2017-02-21). "The Shy Edwardian Filmmaker Who Showed Nature's Secrets to the World". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2019-10-14.

- ^ The Lucky Dog Picturehouse (8 August 2014). "The Birth Of A Flower (1910)". Archived from the original on 2021-12-12 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- ^ Talbot, Frederick Arthur Ambrose (1912). "Chapter XIV: Moving Pictures of Microbes". Moving Pictures. London: Heinemann.

- ^ "Local Man Bares Wonders of Germ Life: Making Moving Pictures of Microbe Drama". San Diego Union. November 3, 1929.

- ^ H. H. Dunn (June 1931). "Movie New Eye of Microscope in War on Germs". Popular Science: 27, 141.

- ^ 360 degree example using this method: 360 degree panning timelapse. 5 May 2007 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Der heilige Gral der Zeitraffer Kinematografie. Möglichkeiten zur Erstellung von Tag zu Nacht Zeitraffern mit DSLR Kameras. Michael Arras (2014) [1]

Further reading

[edit]- ICP Library of Photographers. Roman Vishniac. Grossman Publishers, New York. 1974.

- Roman Vishniac. Current Biography (1967).

- Ott, John (1958). My Ivory Cellar. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781176862326.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Ott, John (1979). Health and Light. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-80537-1.

- Exploring the Spectrum John Ott. (1975; DVD re-issue 2008).

- EBSCO Industries. (2013). From ponies to ProjectCam: The history of time lapse photography. Retrieved from https://www.wingscapes.com/blog/from-peonies-to-the-projectcam-the-history-of-time-lapse-photography/. Archived 2019-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

[edit]Time-lapse photography

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Time-lapse photography is a cinematographic technique in which a series of still photographs are captured at regular intervals over an extended period and then assembled into a video sequence played back at a standard frame rate, such as 24 to 30 frames per second (fps). This results in the illusion of accelerated motion, compressing hours, days, or even years of real-time events into seconds or minutes of footage.[8] The core method involves taking individual frames at a significantly lower rate than the playback speed—typically one frame every 1 to 60 seconds—allowing slow, gradual changes in the subject to become dramatically visible.[2] The fundamental principle behind time-lapse is time compression, achieved through the relationship between the shooting interval and the video's playback rate. The acceleration factor, or speedup ratio, is calculated as the product of the interval duration (in seconds) and the playback fps; for instance, capturing one frame every 1 second and playing back at 30 fps produces a 30x acceleration, making a 30-second real-time event appear as 1 second in the final video.[9] This manipulation alters the perception of time, revealing phenomena that occur too slowly for the human eye to notice in real time, such as the fluid movement of clouds across the sky or the incremental growth of a plant from seed to flower.[8] To maintain visual coherence, the technique requires a stationary camera setup and stable environmental conditions, as any unintended movement or lighting variations can introduce artifacts like jitter or flicker that disrupt the seamless flow.[2] From a perceptual standpoint, time-lapse exploits the human visual system's sensitivity to motion at standard frame rates while compressing temporal scales to make subtle, prolonged processes perceptible within a brief viewing duration.[8] It fundamentally differs from related techniques: unlike stop-motion animation, which creates movement by physically repositioning objects between each frame, time-lapse relies on capturing natural, continuous changes without manual intervention.[8] Similarly, it contrasts with slow-motion videography, where events are recorded at higher-than-normal frame rates (e.g., 60 or 120 fps) and played back at standard rates to decelerate fast actions, rather than accelerating slow ones.[10]History

The origins of time-lapse photography trace back to the late 19th century, when pioneering efforts in sequential imaging laid the groundwork for capturing accelerated motion. In the 1870s, photographer Eadweard Muybridge conducted groundbreaking motion studies, using a battery of 24 cameras to document a galloping horse, creating the first known series of rapid-succession photographs that, when projected, simulated fluid movement and influenced subsequent developments in both stop-motion and time-lapse techniques.[6] This work served as a precursor, though true time-lapse—accelerating natural processes like growth over extended periods—emerged in the early 20th century with naturalists experimenting on plant and insect behaviors. British filmmaker F. Percy Smith advanced the field in the 1910s through films such as The Birth of a Flower (1910), employing hand-cranked cameras and time-lapse to vividly depict petals unfurling and insects in microcosmic activity, establishing it as a tool for revealing hidden natural rhythms.[11] By the mid-20th century, time-lapse gained prominence in scientific and documentary filmmaking, particularly for observing biological processes. In the 1930s, American photographer John Ott revolutionized plant studies by constructing custom interval timers and greenhouses to film accelerated growth sequences, demonstrating how light spectra influenced development and contributing footage to early television broadcasts.[12] Ott's innovations extended into the 1940s and beyond, influencing Walt Disney's Secrets of Life (1956), which featured extensive time-lapse sequences of seeds sprouting and flowers blooming, narrated by Winston Hibler and showcasing the technique's potential for educational storytelling.[13] This period marked time-lapse's integration into mainstream media, with Smith's earlier insect and floral films inspiring broader adoption in nature documentaries. The transition from film to digital in the late 20th century democratized time-lapse, enabling more accessible capture and editing. During the 1970s and 1980s, productions like the BBC's Life on Earth (1979), presented by David Attenborough, utilized time-lapse alongside microphotography to illustrate evolutionary processes and seasonal changes, setting a benchmark for high-production wildlife series.[14] The 2000s saw digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras with built-in intervalometers simplify workflows, allowing photographers to automate frame sequences without manual winding, which expanded its use in environmental and astronomical imaging.[3] By the 2010s, smartphone integration accelerated adoption; Apple's iOS 8 update in 2014 introduced native time-lapse modes on iPhones, automatically adjusting intervals for stabilization, while Android devices followed with apps like Hyperlapse from Instagram, making the technique ubiquitous for casual creators.[15] Recent milestones from 2023 to 2025 highlight AI's role in enhancing accessibility and precision. Cornell University's 2025 software release enables automated time-lapse capture on standard mobile phones using 3D tracking and augmented reality for alignment, allowing users to document subtle environmental changes without specialized gear.[16] Concurrently, AI advancements, such as NVIDIA's 2023 frame interpolation models, upscale low-frame-rate sequences for smoother playback, while growth in drone photogrammetry software, which supports 3D time-lapse applications, is projected to reach $8.7 billion by 2033, integrating drone imagery and machine learning for dynamic modeling of landscapes and structures, aiding fields like ecology and urban planning.[17][18]Terminology

In time-lapse photography, an intervalometer is a device or built-in camera feature that automates the shutter release at predetermined intervals, enabling the capture of sequential frames spaced evenly over time to compress extended events into short videos.[19] This tool is essential for maintaining consistent timing without manual intervention, often allowing intervals as short as 1 second or as long as several minutes depending on the subject.[20] A common challenge in time-lapse sequences is flicker, which refers to unwanted variations in brightness or exposure between consecutive frames, often caused by inconsistent aperture stopping down or fluctuating light conditions during capture.[21] The term Holy Grail describes a specialized time-lapse technique for achieving smooth exposure transitions during significant light changes, such as day-to-night shifts, by gradually adjusting shutter speed, aperture, or ISO to avoid abrupt jumps.[22] Time-lapse acceleration is quantified by the speed multiplier, calculated as the real-time duration of the event divided by the final video length, indicating how much faster the playback appears compared to reality—for instance, a 1-hour event compressed into a 1-minute video yields a 60x multiplier.[23] Distinct from this is the differentiation between capture frame rate (the rate at which photos are taken during shooting, typically low like 1 frame every few seconds) and playback frame rate (the standard video rate, such as 24 or 30 frames per second, at which the sequence is rendered to create fluid motion).[24] Variants of time-lapse include hyperlapse, a dynamic form where the camera moves between frames, transporting the viewer through both space and time while accelerating the scene, often stabilized in post-production for smooth results.[25] Astronomical time-lapse (sometimes referred to as starlapse in certain contexts), focuses on capturing celestial motion, such as star trails or planetary rotations, by recording frames over hours to depict the night sky's apparent movement in a condensed video. Bulb ramping involves automated, incremental adjustments to exposure duration in bulb mode (where the shutter remains open for manually controlled lengths), ensuring consistent brightness across frames in varying light without causing flicker.[26] Key abbreviations in the field encompass HDR (High Dynamic Range), a method in time-lapse that merges multiple exposures per frame to preserve detail in high-contrast scenes like sunsets, expanding tonal range beyond a single exposure's capabilities.[27] Additionally, ISO invariance denotes a camera sensor's property where underexposed images at base ISO, when brightened in post-processing, exhibit noise levels comparable to those shot at higher native ISOs, aiding low-light time-lapses by maximizing dynamic range and minimizing noise amplification.[28]Equipment and Setup

Cameras and Accessories

Time-lapse photography requires cameras capable of capturing sequences of images at set intervals, with key considerations including built-in interval shooting, robust battery life, ample storage, and environmental durability. Digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) and mirrorless cameras remain popular for their versatility and image quality, particularly models with integrated intervalometers. For instance, Canon's EOS R series, such as the EOS R5 and R6 Mark II, feature built-in interval shooting modes that allow users to program sequences directly from the camera menu, supporting high-resolution RAW captures ideal for post-processing.[29][30] These full-frame sensors excel in low-light conditions, providing better dynamic range compared to APS-C sensors, which is crucial for extended shoots like astrophotography or urban night transitions.[31] Compact and action cameras offer portability and ruggedness for dynamic or outdoor time-lapses. The GoPro Hero13 Black, updated in 2024 with ongoing firmware support into 2025, includes dedicated time-lapse, hyperlapse, and night lapse modes, capturing up to 4K video sequences with a waterproof design up to 33 feet without housing.[32] Similarly, the DJI Osmo Action 5 Pro provides 40MP stills and built-in stabilization for smooth sequences, with up to 4 hours of battery life on a single charge and microSD support up to 1TB for storing thousands of frames.[33] These cameras prioritize ease of use in harsh environments, such as hiking or construction sites, where their compact form factor allows mounting on drones or vehicles. Dedicated time-lapse cameras are engineered specifically for prolonged, unattended operation, often with solar power integration and weatherproofing for applications like construction monitoring. The Brinno TLC 2020, a compact model from 2020 with 2025 firmware updates that improve low-battery indication accuracy, uses AA batteries to achieve up to 99 days of shooting at 5-minute intervals with lithium batteries, storing footage on SD cards up to 128GB in MP4 format for immediate playback.[34][35] The ENLAPS Tikee 3 Pro+, released in 2023 and enhanced for 2025, features up to 6K panoramic resolution, 360-degree panoramic capture, and IP66 weather resistance, with a 45.4Wh battery supporting weeks of continuous recording and 1TB SSD storage for high-volume projects.[36][33][37] Another option, the Brinno TLC 300, offers 1080p video with a fisheye lens for wide-field views, emphasizing low power consumption for remote deployments.[34] Smartphones have become viable for casual time-lapse work, leveraging built-in camera apps and third-party software. Modern iOS and Android devices, such as the iPhone 16 series and Google Pixel 9, include native time-lapse modes in their camera apps that use automatic intervals adjusted for 20-40 second output videos, with stabilization; manual intervals from 0.5 to 60 seconds are available via third-party apps.[16] In 2025, Cornell University's Pocket Time-lapse software enables automated environmental monitoring via AI-guided alignment, allowing users to capture aligned frames over days using a phone's sensors for precise positioning without fixed mounts.[16] Essential accessories enhance stability, power endurance, and image control during long exposures. Sturdy tripods, such as carbon fiber models from Manfrotto or Gitzo, provide vibration-free support for multi-hour shoots, with quick-release plates for easy setup.[33] External power solutions, including dummy batteries or solar panels like those bundled with the ENLAPS Tikee, extend operation beyond internal limits— for example, enabling 10,000+ shots without recharging.[36] Neutral density (ND) filters, such as variable models from Neewer, reduce light intake for consistent daylight exposures, preventing overexposure in bright conditions.[38] Weatherproof cases and rain covers, often IP67-rated, protect gear from elements during outdoor endurance tests.[33] When selecting equipment, prioritize battery life for unattended shoots—aim for at least 10,000 frames on a charge or AA/solar compatibility—along with storage capacity like 1TB SD cards to handle raw sequences.[33] Sensor size influences low-light performance, with full-frame options like the Nikon Z8 outperforming APS-C in noise reduction for night-to-day transitions, though the latter suffices for most daytime work.[31] Durability ratings (e.g., IP66) and built-in interval features streamline setup, ensuring reliability in field conditions up to 2025 standards.[36]Intervalometers and Automation

Intervalometers are essential devices or built-in camera features that automate the timing of frame captures in time-lapse photography, ensuring consistent intervals between exposures to produce smooth sequences.[39] Built-in intervalometers, accessible via camera menus, are available in many Nikon DSLRs such as the D5100 and later models, as well as current Pentax DSLRs, allowing users to program shooting intervals directly without additional hardware.[40][41] External intervalometers come in wired and wireless varieties; wired models, like the Insignia Universal Wired Digital Interval Timer, connect via cable for precise control, while wireless options, such as the MIOPS Smart+, offer app-based control and help minimize vibrations from physical contact with the camera.[42][43] Key features of intervalometers include programmable intervals ranging from 0.1 seconds to up to 99 hours, 59 minutes, and 59 seconds, enabling flexibility for short bursts or extended sequences like celestial events.[44] Advanced models support ramping functions, which gradually adjust exposure or ISO settings across frames to handle changing light conditions, as seen in devices like the LRTimelapse PRO Timer 3.[45] Some intervalometers and compatible apps also facilitate GPS tagging by integrating with external GPS units, embedding location data into image metadata for long-term shoots such as environmental monitoring.[46] As of 2025, AI enhancements are emerging in intervalometer apps and companion software, incorporating adaptive algorithms that detect motion or light shifts to optimize capture timing automatically, improving efficiency in dynamic scenes.[47] Integration with drones is advancing, allowing intervalometers to synchronize with automated panning and flight paths for aerial time-lapses, as demonstrated in DJI drone systems with built-in timelapse modes.[48] Setup considerations for intervalometers include selecting appropriate cable lengths for wired models—typically around 85 cm, with extensions available up to several meters to avoid signal loss during remote triggering.[49] Regular firmware updates, such as those delivered via mobile apps for the MIOPS Smart+, enhance reliability and compatibility with new camera models.[50] To prevent issues in prolonged use, users should monitor for overheating in the camera body by incorporating breaks in sequences or using external power sources, as continuous shooting can strain internal components.[51]Core Methodology

Basic Shooting Process

The basic shooting process for time-lapse photography begins with thorough planning to ensure the sequence captures the intended motion effectively. Photographers select subjects that exhibit gradual or repetitive changes, such as drifting clouds or urban traffic flows, to highlight time's passage in a compelling way.[52] Site scouting is essential, focusing on locations that provide a stable vantage point free from obstructions and vibrations, allowing for uninterrupted recording over extended periods.[53] To determine the required parameters, calculate the total number of shots based on the event duration, desired playback speed, and frame rate; for instance, capturing a 4-hour event (14,400 seconds) at 2-second intervals yields 7,200 frames, which at 30 frames per second produces a 4-minute video.[52] Once planned, setup involves securing the camera on a sturdy tripod to maintain a fixed position throughout the shoot.[53] Compose the frame slightly wider than the anticipated final crop to accommodate minor adjustments in post-production, and verify a level horizon using the camera's built-in tools or an external bubble level to prevent distracting tilts.[52] During capture, switch the camera to manual mode to lock exposure settings, including a fixed ISO (such as 100 for low noise) and aperture (e.g., f/8 or f/11 for depth of field), and set focus to manual and lock it on the subject to ensure consistency across frames, ensuring consistency across frames and avoiding flicker from auto adjustments.[53][52] Activate the intervalometer to automate shots at the predetermined interval, then start the sequence while periodically checking for issues like depleting battery life or filling memory cards, which may require spare batteries or high-capacity media.[52] Common pitfalls in static time-lapse shooting include camera overheating during prolonged sessions, which can be mitigated by incorporating longer intervals to allow cooling pauses between exposures or enabling silent shooting modes to reduce internal heat generation.[53] Wind-induced shake poses another risk, addressable by weighting the tripod base with sandbags or selecting sheltered locations to minimize vibrations that could blur frames.[52]Plant Growth Time-Lapse with a Smartphone

Creating a time-lapse of plant growth using a smartphone follows the core shooting principles but adapts to the device's capabilities for long-duration captures. The process emphasizes stability, consistent power and lighting, and appropriate intervals suited to slow biological changes.[54]- Secure the smartphone on a tripod or stable base to prevent any movement, ensuring a fixed viewpoint over the extended period.[54]

- Connect the device to a charger to support prolonged recordings without battery depletion.[54]

- Provide constant artificial lighting, such as LED or grow lights, to avoid variations from changing sunlight and maintain exposure consistency.[54]

- Set the shooting interval based on the plant's growth rate, typically 5 to 30 minutes per frame, calculated to capture the desired progression without excessive file volume.[54]

- Initiate the sequence to run for days or weeks as needed, then use a dedicated app to compile the images into a video.[55]