Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vandalia (colony)

View on Wikipedia

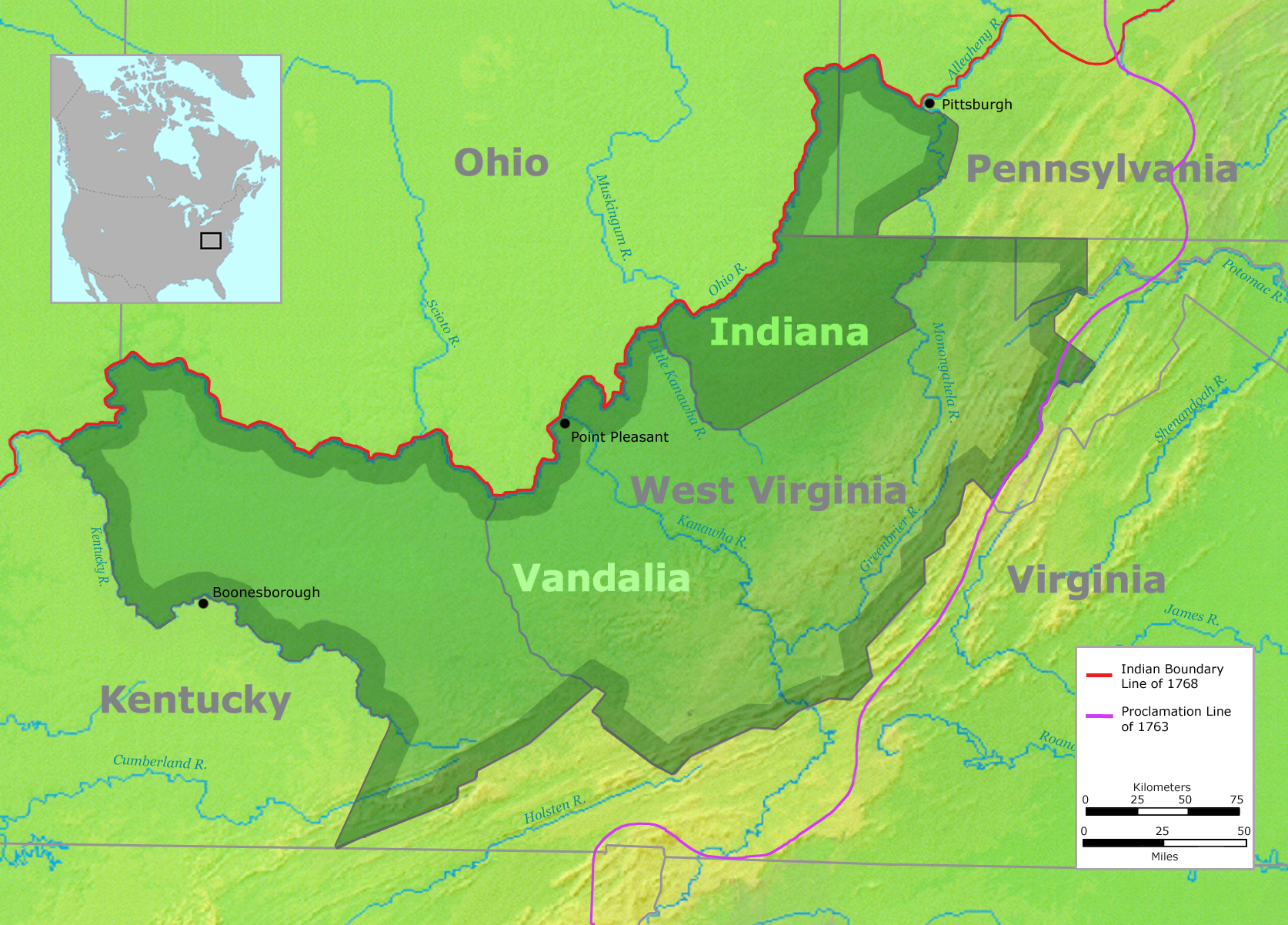

Vandalia was the name in the late 18th century of a proposed British colony in North America. The colony would have been located south of the Ohio River, primarily in what are now West Virginia and northeastern Kentucky.

Vandalia was never approved by the British Crown and had no colonial government, although some Virginians and Pennsylvanians had already settled there. After the American Revolutionary War, the Vandalia settlers sought unsuccessfully to be admitted as a state called Westsylvania. However, they had no legal title to the land and were opposed by the governments of Virginia and Pennsylvania, which both claimed the area as their own under colonial charters. Ultimately, the federal government split the area between Pennsylvania and Virginia according to the Mason–Dixon line.[1] Kentucky was later settled by Virginians and admitted as a state; West Virginia was admitted as a state in 1863, during the American Civil War.

History

[edit]

In the 18th century, British land speculators several times attempted to colonize the Ohio Valley, most notably in 1748 when the British Crown granted a petition of the Ohio Company for 200,000 acres (800 km2) near the "Forks of the Ohio" (present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania).[2] The French and Indian War (1754–63) and Pontiac's Rebellion (1763–66) delayed settlement of the region.[3]

After Pontiac's Rebellion, merchants who had lost their trade items during the conflict formed a group known as the "suffering traders", later to become the Indiana Company. In the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768), the British required the Iroquois to give the "suffering traders" a grant of land. Those who benefited the most were Samuel Wharton and William Trent. Known as the "Indiana Grant", this land was located along the Ohio River and included part of the Iroquois' hunting ground, which they had controlled since the 17th century.[4] When Wharton and Trent sailed to England in 1769 seeking to have their grant confirmed, they joined forces with the Ohio Company to form the Grand Ohio Company, also called the Walpole Company.

The Grand Ohio Company eventually received a larger area of land than the Indiana Grant.[5] The development companies planned a new colony, initially called "Pittsylvania" (Wright 1988:212) but later known as Vandalia, in honor of the British queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744–1818), who was thought to be descended from Vandalic tribesmen.[6][7][8]

Opposition from rival interest groups[9] and the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) prevented the development of Vandalia as a full colony.[10] During the Revolutionary War, some settlers in the region petitioned the American Continental Congress to recognize a new province to be known as Westsylvania, which had approximately the same borders as the earlier Vandalia proposal. As both the states of Virginia and Pennsylvania claimed the region, they blocked recognition of a new state.[11] The Indiana Company presented a bill in equity against the State of Virginia concerning their claims, but the ruling in Chisholm v. Georgia led to the Eleventh Amendment forbidding suits by citizens of another State, and the Supreme Court dismissed the Indiana Company's suit, holding the constitutional amendment applied retroactively.

The formation of the state of Kentucky in 1792 and the separation of West Virginia from Virginia in 1863, established the present political borders in the region.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cranmer, History of the Upper Ohio, 1:59–63

- ^ Anderson, James Donald, "Vandalia: The First West Virginia?" West Virginia History, Volume 40, No. 4 (Summer 1979), pp. 375-92 online

- ^ Cecil B. Currey, Road to Revolution: Benjamin Franklin in England, 1765-1775 (1968) pp 248-54

- ^ Marshall, "Lord Hillsborough, Samuel Wharton, and the Ohio Grant, 1769- 1775" English Historical Review (1965), 80:717-18

- ^ Croghan to T. Wharton, December 9, 1773, "Letters of George Croghan," PMHB, XV (1891), 436-37. Any migration westward could help Croghan sell some of his own lands at Fort Pitt. James Donald Anderson, 1978

- ^ Otis K. Rice and Stephen W. Brown. West Virginia: A History. 2nd Ed. University Press of Kentucky, 1994. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8131-1854-3

- ^ David W. Miller. The Taking of American Indian Lands in the Southeast: A History of Territorial Cessions and Forced Relocations, 1607-1840. McFarland, 2011. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7864-6277-3

- ^ Thomas J. Schaeper. Edward Bancroft: Scientist, Author, Spy. Yale University Press, 2011. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-300-11842-1

- ^ Gipson, Lawrence Henry, The British Empire Before the American Revolution, 15 vols. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946-1970, IX 457-88

- ^ Carter, Clarence Edwin, Great Britain and the Illinois Country, 1763-1773, Port Washington, N.Y: Kennikat Press, 1970

- ^ Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. Western Lands and the American Revolution. 1937/New York: Russell & Russell, 1959

Sources

[edit]- Alvord, Clarence W. The Mississippi Valley in British Politics, vol. 1. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur Clark, 1917.

- Marshall, Peter. "Lord Hillsborough, Samuel Wharton, and the Ohio Grant, 1769- 1775", English Historical Review (1965) Vol. 80, No. 317 pp. 717–739 in JSTOR

- Steeley, James V., "Old Hanna's Town and the Westward Movement, 1768 - 1787: Vandalia the Proposed 14th American Colony", Westmoreland History, Spring 2009, pp. 20–26, published by Westmoreland County Historical Society

- Wright, Esmond, 'Franklin of Philadelphia' , Harvard University Press, 1988