Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ohio Company

View on Wikipedia

The Ohio Company, formally known as the Ohio Company of Virginia, was a land speculation company organized for the settlement by Virginians of the Ohio Country (approximately the present U.S. state of Ohio) and to trade with the Native Americans. The company had a land grant from Britain and a treaty with Indians, but France also claimed the area, and the conflict helped provoke the outbreak of the French and Indian War.[1]

Formation

[edit]Virginian explorers recognized the potential of the Ohio region for colonization and moved to capitalize on it,[2] as well as to block French expansion into the territory.[1] In 1748,[2] Thomas Lee and brothers Lawrence and Augustine Washington organized the Ohio Company to represent the prospecting and trading interests of Virginian investors including Robert Dinwiddie; George Washington; George Mason; John Mercer (colonial lawyer) and sons George Mercer, James Mercer & John Francis Mercer; Richard "Squire" Lee; Thomas Ludwell Lee; Phillip Ludwell Lee; Robert Carter III of Nomoni; John Tayloe II of Mount Airy; and Gawin Corbin, son of Henry Corbin (colonist).[3][4]

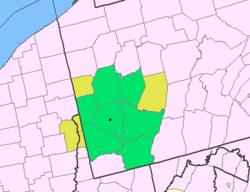

In addition to the mandate and investment of Virginia Royal Governor Robert Dinwiddie,[5] other original members included John Hanbury, Colonel Thomas Cresap, George Mercer, John Mercer, and "all of His Majesty's Colony of Virginia." In that same year, George Mercer petitioned King George for land in the Ohio country,[5] and in 1749, the British Crown granted the company 500,000 acres in the Ohio Valley between the Kanawha River and the Monongahela.[6] The grant was in two parts: the first 200,000 acres were promised, and the following 300,000 acres were to be granted if the Ohio Company successfully settled one hundred families within seven years.[7] Furthermore, the Ohio Company was required to construct a fort and provide a garrison to protect the settlement at their own expense. But the land grant was rent and tax free for ten years to facilitate settlement.[8]

The organizers signed a treaty of friendship and permission at Logstown with the main tribes in the region in 1752 .[8] A rival group of land speculators from Virginia, the Loyal Company of Virginia, was organized about the same time, and included influential Virginians such as Thomas Walker, William Cabell and Peter Jefferson (father of Thomas Jefferson).

In 1752 George Mason, later to become a major founding father, became treasurer of the Ohio Company, a post he held for forty years until his death in 1792.

French and Indian War

[edit]

In 1748–1750, the Ohio Company hired Thomas Cresap, who had opened a series of trading posts along the Potomac River at Long Meadow, Oldtown and Will's Creek (on the foot of the eastern climb up the Cumberland Narrows along what was soon to be called the Nemacolin Trail). Cresap contracted to blaze a small road over the Appalachian Mountains to the Monongahela River, and then to start widening this road into a wagon road. Though not known at the time, that route was one of only three mid-mountain-range crossings of the Appalachian Ridge and Valley system between the northern Hudson-Great Lakes route, and the southern Georgia-Mississippi-Western Tennessee plains route.

In 1750, the Ohio Company established a fortified storehouse at what became Ridgeley, Virginia across the Potomac River from the Will's Creek trading post. That year the Ohio Company also hired Christopher Gist, a skillful woodsman and surveyor, to explore the Ohio Valley in order to identify lands for potential settlement. He surveyed and estimated the area drained by the Kanawha River as well as that drained by other tributaries of the Ohio River, and returned in 1751 and 1753. His journals provide valuable insights of the greater Ohio Valley as well as the Alleghenies. Gist travelled as far west as the Miami Indian village of Pickawillany (near present Piqua, Ohio). Relying on his report, the Ohio Company began selling land in what later became Western Pennsylvania and present-day West Virginia. Gist and Cresap both received sizable land grants west of the Appalachians. In 1752 the company had a pathway blazed between the small fortified posts at Wills Creek (that became Cumberland, Maryland), and Redstone Old Fort (that became Brownsville, Pennsylvania). Cresap and his scout Nemacolin had established the latter location in 1750, which overlooked Redstone Creek and the longstanding Monongahela River ford.

Conflicting land claims complicated settlement efforts. The Ohio Country tract ceded by the King through Virginia's Governor Dinwiddie included, in Dinwiddie's opinion, the "forks of the Monongahela," present-day Pittsburgh. The Pennsylvania colonial government also claimed much of this territory (though Maryland's charter ended at the Appalachian divide, and while the charter of Virginia set no western boundary, Pennsylvania's grant was for 5 degrees of longitude from the Delaware River, a SW point not determined until after the Mason Dixon survey). Moreover, France also claimed land in North America, including everything drained by the Mississippi River (the Ohio River being one of the great river's tributaries). Not only did French traders compete with those of the Ohio Company and agents of other British-chartered entities, France had also sent soldiers, who were fighting for their kingdom's right to occupy the Ohio Valley, most notably at Fort Duquesne.[8] Dinwiddie responded by sending a military unit under the command of George Washington to the region,[9] which led to the outbreak of the French and Indian War.

Post-war efforts

[edit]In 1763, the Ohio Company sent a representative to petition the British Crown for a grant renewal. The plans for settlement and military development continued, with Henry Bouquet's 1764 plans to construct military posts around prospective western settlements.[10] However, following Pontiac's War, land claims west of the Appalachian Mountains were forfeited to the Native American tribes in the Proclamation of 1763, requiring them to be re-purchased through King George III.[11]

Grand Ohio Company

[edit]

In 1768, the British government authorized Sir William Johnson to make the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, purchasing land rights from the Iroquois, in accordance with the Proclamation of 1763.[12][13] Samuel Wharton and William Trent applied for a "despoiled traders" (frontiersmen who had been aggrieved by the various Indian raids during and after the French and Indian Wars) land grant in 1768. In order to get approved by the British Crown, they joined with a number of other land speculators to form the Walpole Company,[10] named for Thomas Walpole, a British lawyer involved in the endeavor.[7] The company wanted to acquire 2.5 million acres of Ohio Country land. Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin was one of the seventy-two shareholders, as well as included Franklin's son William (then Royal Governor of New Jersey), George Croghan and Sir William Johnson, as well as Franklin's perennial London allies William Strahan and Richard Jackson. The Walpole Company, Indiana Company, and members of the Ohio Company reorganized, and on December 22, 1769, formed the Grand Ohio Company.[14] In 1772, the Grand Ohio Company received from the British government a grant of a large tract lying along the southern bank of the Ohio as far west as the mouth of the Scioto River.[15] A colony to be called "Vandalia" was planned. However, the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War interrupted colonization and nothing was accomplished. The London-based company ceased operations in 1776.

The Ohio Company of Associates was organized in 1786, composed largely of New England veterans who had certificates for land from Congress for their services during the Revolution.[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b MacCorkle, William Alexander. "The historical and other relations of Pittsburgh and the Virginias". Historic Pittsburgh General Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b Consolidated Illustrating Company. "Allegheny County Pennsylvania: illustrated". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Rowland, Kate Mason. "The Ohio Company." The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4, 1893, pp. 197–203, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939709. Accessed 8 May 2022.

- ^ Andrew Arnold Lambing; et al. "Allegheny County: its early history and subsequent development: from the earliest period till 1790". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Ohio Company Papers Finding Aid". Ohio Company Papers, 1736–1813, DAR.1925.02, The Darlington Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Emilius Oviatt Randall, Daniel Joseph Ryan (1912). History of Ohio: The Rise and Progress of an American State, Volume 1. p. 216.

- ^ a b Ambler, Charles Henry. "George Washington and the West". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Thurston, George H. "Allegheny county's hundred years". Historic Pittsburgh General Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ wvculture.org: "Instructions for George Washington", n.d. extracted from The Writings of George Washington, Volume II, by Jared Sparks (Boston: Charles Tappan, 1846), pp. 184–186.

- ^ a b Buck, Solon J. "The planting of civilization in western Pennsylvania". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Native American". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ Kelly, George Edward. "Allegheny County, a sesqui-centennial review". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ "Treaties of Fort Stanwix". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Volwiler, Albert T. "George Croghan and the westward movement, 1741–1782". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ohio Company". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32.

- ^ The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company (1796, reprinted 2008)

References

[edit]- Abernethy, Thomas Perkins. Western Lands and the American Revolution. New York: Russell & Russell, 1959.

- Bailey, Kenneth P. The Ohio Company of Virginia and the Westward Movement, 1748–1792. Originally published 1939. Reprinted Lewisburg: Wennawoods Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-889037-25-7.

- Procter, James, Alfred. The Ohio Company: Its Inner History. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1959.

- Randall, Emilius; Ryan, Daniel Joseph (1912). History of Ohio: the Rise and Progress of an American State. Vol. 1. New York: The Century History Company. p. 211.

- Mulkearn, Lois, ed. George Mercer Papers Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1954. Collection of many original documents, including Christopher Gist's journal.