Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Invictus

View on Wikipedia| Invictus | |

|---|---|

| by William Ernest Henley | |

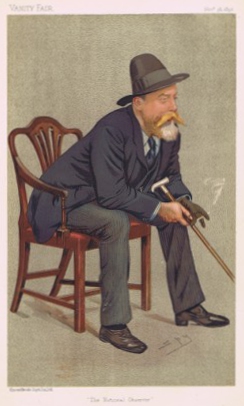

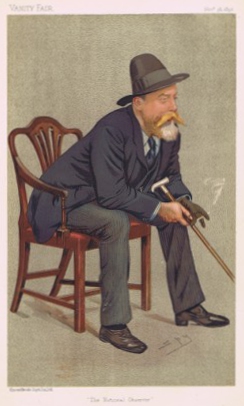

Portrait of William Ernest Henley by Leslie Ward, published in Vanity Fair, 26 November 1892. | |

| Written | 1875 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

"Invictus" is a short poem by English poet William Ernest Henley. Henley wrote it in 1875, and in 1888 he published it in his first volume of poems, Book of Verses, in the section titled "Life and Death (Echoes)".

Background

[edit]

When Henley was 16 years old, his left leg required amputation below the knee owing to complications arising from tuberculosis.[1]: 16 In the early 1870s, after seeking treatment for problems with his other leg at Margate, he was told that it would require a similar procedure.[2]

He instead chose to travel to Edinburgh in August 1873 to enlist the services of the distinguished English surgeon Joseph Lister,[1]: 17–18 [3] who was able to save Henley's remaining leg after multiple surgical interventions on the foot.[4] While recovering in the infirmary, he was moved to write the verses that became the poem "Invictus". A memorable evocation of Victorian stoicism—the "stiff upper lip" of self-discipline and fortitude in adversity, which popular culture rendered into a British character trait—"Invictus" remains a cultural touchstone.[5]

Poem

[edit]INVICTUS

Out of the night that covers me

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance,

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate

I am the captain of my soul.

Analysis

[edit]Latin for "unconquered",[6] the poem "Invictus" is a deeply descriptive and motivational work filled with vivid imagery. With four stanzas and sixteen lines, each containing eight syllables, the poem has a rather uncomplicated structure.[7] The poem is most known for its themes of willpower and strength in the face of adversity, much of which is drawn from the horrible fate assigned to many amputees of the day—gangrene and death.[8]

Each stanza takes considerable note of William Ernest Henley's perseverance and fearlessness throughout his early life and over twenty months under Lister's care.[7] In the second stanza, Henley refers to the strength that helped him through a childhood defined by his struggles with tuberculosis when he says "I have not winced nor cried aloud."[2][9] In the fourth stanza, Henley alludes to the fact that each individual's destiny is under the jurisdiction of themselves, not at the mercy of the obstacles they face, nor other worldly powers.

Those who have taken time to analyze "Invictus" have also taken notice of religious themes, or the lack thereof, that exist in this piece. There is agreement that much of the dark descriptions in the opening lines make reference to Hell. Later, the fourth stanza of the poem alludes to a phrase from Jesus's Sermon on the Mount in the King James Bible, which says, at Matthew 7:14, "Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it."

Despite Henley's evocative tellings of perseverance and determination, worry was on his mind; in a letter to a close companion, William Ernest Henley later confided, "I am afeard my marching days are over"[7] when asked about the condition of his leg.

Publication history

[edit]The second edition of Henley's Book of Verses added a dedication "To R. T. H. B."—a reference to Robert Thomas Hamilton Bruce, a successful Scottish flour merchant, baker, and literary patron.[10] The 1900 edition of Henley's Poems, published after Bruce's death, altered the dedication to "I. M. R. T. Hamilton Bruce (1846–1899)," whereby I. M. stands for "in memoriam."[11]

Title

[edit]The poem was published in 1888 in his first volume of poems, Book of Verses, with no title,[12] but would later be reprinted in 19th-century newspapers under various titles, including:

- "Myself"[13]

- "Song of a Strong Soul"[14]

- "My Soul"[15]

- "Clear Grit"[16]

- "Master of His Fate"[17]

- "Captain of My Soul"[18]

- "Urbs Fortitudinis"[19]

- "De Profundis"[20]

The established title "Invictus" was added by editor Arthur Quiller-Couch when the poem was included in the Oxford Book of English Verse (1900).[21][22]

Notable uses

[edit]History

[edit]- In a speech to the House of Commons on 9 September 1941, Winston Churchill paraphrased the last two lines of the poem, stating "We are still masters of our fate. We still are captains of our souls."[23]

- Nelson Mandela, while incarcerated at Robben Island prison, recited the poem to other prisoners and was empowered by its message of self-mastery.[24][25]

- Former State Counsellor of Myanmar and Nobel Peace laureate[26] Aung San Suu Kyi stated: "This poem had inspired my father, Aung San, and his contemporaries during the independence struggle, as it also seemed to have inspired freedom fighters in other places at other times."[27]

- The poem was read by U.S. prisoners of war during the Vietnam War. James Stockdale recalls being passed the last stanza, written with rat droppings on toilet paper, from fellow prisoner David Hatcher.[28]

- The phrase "bloody, but unbowed" was the headline used by the Daily Mirror on the day after the 7 July 2005 London bombings.[29]

- The poem's last stanza was quoted by U.S. President Barack Obama at the end of his speech at the memorial service of Nelson Mandela in South Africa (10 December 2013), and published on the front cover of the 14 December 2013 issue of The Economist.[30]

- The poem was chosen by Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh as his final statement before his execution.[31][32][33]

- The perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand in 2019 cited "Invictus".[34]

- According to his sister, before becoming a civil rights leader, Congressman John Lewis used to recite the poem as a teenager and continued to refer to it for inspiration throughout his life.[35]

- Verse "Out of the night that covers me" and phrases "Bloody, but unbowed" and "Captain of my soul" are used as titles of all three parts of Prince Harry's memoir Spare (published in 2023). The poem is also mentioned as the author reminisces his involvement in the Invictus Games.[36]

Literature

[edit]- In Oscar Wilde's De Profundis letter in 1897, he reminisces that "I was no longer the Captain of my soul."

- In Book Five, chapter III ("The Self-Sufficiency of Vertue") of his early autobiographical work, The Pilgrim's Regress (1933), C. S. Lewis included a quote from the last two lines (paraphrased by the character Vertue): "I cannot put myself under anyone's orders. I must be the captain of my soul and the master of my fate. But thank you for your offer."

- In W. E. B. Du Bois' The Quest of the Silver Fleece, the last stanza is sent anonymously from one character to another to encourage him to stay strong in the face of tests to his manhood.

- In "Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit," by P.G. Wodehouse, Jeeves refers to the phrase "bloody but unbowed" in relation to Bertie Wooster, highlighting Bertie's resilience despite his troubles.

- The phrase "bloody, but unbowed" was quoted by Lord Peter Wimsey in Dorothy Sayers' novel Clouds of Witness (1926), referring to his (temporary) failure to exonerate his brother of the charge of murder.[37]

- In Huey Long’s 1935 book ‘’My First Days in the White House,’’ Huey Long fantasizes about a speculative cartoon published in the newspapers in which an unflattering image of himself among the words “Invictus.”

- The last line in the poem is used as the title for Gwen Harwood's 1960 poem "I am the Captain of My Soul", which presents a different view of the titular captain.

Film

[edit]- In Casablanca (1942), Captain Renault (played by Claude Rains) recites the last two lines of the poem when talking to Rick Blaine (played by Humphrey Bogart), referring to his power in Casablanca. While delivering the last line, he is called away by an aide to Gestapo officer Major Strasser.[38]

- In Kings Row (1942), psychiatrist Parris Mitchell (played by Robert Cummings) recites the first two stanzas of "Invictus" to his friend Drake McHugh (played by Ronald Reagan) before revealing to Drake that his legs were unnecessarily amputated by a cruel doctor. In the next and final scene, as Parris rushes to reunite with his love Elise (played by Kaaren Verne), the last two lines are sung as a chorus to the melody of the main theme music.

- In Sunrise at Campobello (1960), the character Louis Howe (played by Hume Cronyn) reads the poem to Franklin D. Roosevelt (played by Ralph Bellamy). The recitation is at first light-hearted and partially in jest, but as it continues both men appear to realize the significance of the poem to Roosevelt's fight against his paralytic illness.

- Nelson Mandela is depicted in Invictus (2009) presenting a copy of the poem to Francois Pienaar, captain of the national South African rugby team, for inspiration during the Rugby World Cup—though at the actual event he gave Pienaar a text of "The Man in the Arena" passage from Theodore Roosevelt's Citizenship in a Republic speech delivered in France in 1910.[39]

- The last two lines "I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul" are shown in a picture during the 25th minute of the film The Big Short (2015).

- Star Trek: Renegades (2015) opens with Lexxa Singh reciting the poem and writing it on the wall of her prison cell.

Television

[edit]- In the 5th episode of the 2nd season of Archer, "The Double Deuce" (2011), Woodhouse describes Reggie as "in the words of Henley, 'bloody, but unbowed'".

- In the 8th episode of the 5th season of TV series The Blacklist, "Ian Garvey", Raymond 'Red' Reddington (played by James Spader) reads the poem to Elizabeth Keen when she wakes up from a ten-month coma.

- In the 6th episode of the third season of One Tree Hill, "Locked Hearts & Hand Grenades" (2006), Lucas Scott (played by Chad Michael Murray) references the poem in an argument with Haley James Scott (played by Bethany Joy Lenz) over his heart condition and playing basketball. The episode ends with Lucas reading the whole poem over a series of images that link the various characters to the themes of the poem.

- In season 1, episode 2 of New Amsterdam, "Ritual", Dr. Floyd Reynolds (played by Jocko Sims) references the poem while prepping hands for surgery prior to a conversation with his fellow doctor Dr. Lauren Bloom (played by Janet Montgomery).

- In the episode "Interlude" of the series The Lieutenant, the lead character and the woman he is infatuated with jointly recite the poem after she has said it is her favorite poem. His reciting is flawed by lapses, which she fills in.

- In season 4, episode 14 of New Amsterdam, "...Unto the Breach", Dr. Floyd Reynolds (played by Jocko Sims) recites the poem while prepping for surgery.

- In season 1, episode 3 of Hulu's Nine Perfect Strangers, Napoleon Marconi (played by Michael Shannon) references the poem in his one-on-one with Masha (played by Nicole Kidman) when referring to his son who died by suicide. Napoleon states, "Zach chose to be the master of his fate" referencing the line "I am the master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul" by Henley.

- In episode 22, season 5 of 30 Rock, “Everything Sunny All the Time Always”, Jack Donaghy quotes the last two lines of the poem in to Liz Lemon.

Sports

[edit]- Jerry Kramer recited the poem during his NFL Pro Football Hall of Fame induction speech.[40]

- The Invictus Games—The Invictus games were founded by Prince Harry, the Ministry of Defense, and Sir Keith Mills. Prior to the inaugural games in London in 2014, entertainers including Daniel Craig and Tom Hardy, and athletes including Louis Smith and Iwan Thomas, read the poem in a promotional video.[41][42]

Video games

[edit]- The second stanza is recited by Lieutenant-Commander Ashley Williams in the 2012 video game Mass Effect 3

- The game Sunless Sea features an "Invictus Token" for players who forgo the right to create backups of their current game state. The item text includes the last two lines of the poem.

- The poem was recited in an early commercial for the Microsoft Xbox One.

- The game Robotics;Notes features the last two lines of the poem in its epigraph.

Music

[edit]- Invictus was set to music by Bruno Huhn in 1910 published by The Arthur P. Schmidt Co.

- The lines "I am the master of my fate... I am the captain of my soul" are paraphrased in Lana Del Rey's song "Lust for Life" featuring The Weeknd. The lyrics are changed from "I" to "we," alluding to a relationship.

- Belgian Black / Folk Metal band Ancient Rites use the poem as a song on their album Rvbicon (Latin form of Rubicon)

- The prominent classical contemporary Indonesian composer Ananda Sukarlan (b. 1968) made a song for soprano, cello and piano in 2023. It was premiered by the soprano Ratnaganadi Paramita in Jakarta, Indonesia.

- The Canadian punk band D.O.A. released a record entitled Bloodied but Unbowed (The Damage to Date 1978-83) in 1983.

- British composer Howard Goodall created a setting of the Passion narrative in 2017 titled "Invictus: A Passion". The work uses many texts in telling the story but the titular movement features this poem in its entirety. The composer's notes may be found here.

See also

[edit]- If—, Rudyard Kipling

- The Man in the Arena, Theodore Roosevelt

- "Let No Charitable Hope," Elinor Wylie

- Agency (philosophy)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goldman, Martin (1987). Lister's Ward. Adam Hilger. ISBN 0852745621.

- ^ a b Faisal, Arafat (Oct 2019). "Reflection of William Ernest Henley's Own Life Through the Poem Invictus" (PDF). International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science. 4: 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-07 – via Google Scholar.

- ^ Cohen, Edward (April 2004). "The second series of W. E. Henley's hospital poems". Yale University Library Gazette. 78 (3/4): 129. JSTOR 40859569.

- ^ "Invictus analysis". jreed.eshs Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spartans and Stoics – Stiff Upper Lip – Icons of England Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 20 February 2011

- ^ "Latinitium – Online Latin Dictionaries". Latinitium. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Edward H. (1974). "Two Anticipations of Henley's 'Invictus'". Huntington Library Quarterly. 37 (2): 191–196. doi:10.2307/3817033. ISSN 0018-7895. JSTOR 3817033. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ "Gangrene – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-30.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (July 17, 1889). A book of verses /. New York. hdl:2027/hvd.hwk9sr.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (1891). A book of verses (Second ed.). New York: Scribner & Welford. pp. 56–57. hdl:2027/hvd.hwk9sr.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (1900). Poems (Fourth ed.). London: David Nutt. p. 119.

- ^ Henley, William Ernest (1888). A book of verses. London: D. Nutt. pp. 56–57. OCLC 13897970. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ "Myself". Weekly Telegraph. Sheffield (England). 1888-09-15. p. 587.

- ^ "Song of a Strong Soul". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Pittsburgh, PA. 1889-07-10. p. 4.

- ^ "My Soul". Lawrence Daily Journal. Lawrence, KS. 1889-07-12. p. 2.

- ^ "Clear Grit". Commercial Advertiser. Buffalo, NY. 1889-07-12. p. 2.

- ^ "Master of His Fate". Weekly Times-Democrat. New Orleans, LA. 1892-02-05. p. 8.

- ^ "Captain of My Soul". Lincoln Daily Call. Lincoln, NE. 1892-09-08. p. 4.

- ^ "Urbs Fortitudinis". Indianapolis Journal. Indianapolis, IN. 1896-12-06. p. 15.

- ^ "De Profundis". Daily World. Vancouver, BC. 1899-10-07. p. 3.

- ^ Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch, ed. (1902). The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250–1900 (1st (6th impression) ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1019. hdl:2027/hvd.32044086685195. OCLC 3737413.

- ^ Wilson, A.N. (2001-06-11). "World of books". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ "Famous Quotations and Stories" Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine. Winston Churchill.org.

- ^ Boehmer, Elleke (2008). "Nelson Mandela: a very short introduction". Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192803016.

Invictus, taken on its own, Mandela clearly found his Victorian ethic of self-mastery

- ^ Daniels, Eddie (1998) There and back

- ^ Independent, 8/30/17

- ^ Aung San Suu Kyi. 2011. "Securing Freedom Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine" (lecture transcript). Reith Lectures, Lecture 1: Liberty. UK BBC Radio 4.

- ^ Stockdale, James (1993). "Courage Under Fire: Testing Epictetus's Doctrines in a Laboratory of Human Behavior" (PDF). Hoover Institution, Stanford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2014-12-31.

- ^ "UK News". mirror. Archived from the original on 2023-10-14. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- ^ "The Economist Dec 14th, 2013". The Economist. Archived from the original on 2014-01-09. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Quayle, Catherine (June 11, 2001). "Execution of an American Terrorist". Court TV. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ Cosby, Rita (June 12, 2001). "Timothy McVeigh Put to Death for Oklahoma City Bombings". FOX News. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "McVeigh's final statement". the Guardian. 2001-06-11. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ Kornhaber, Spencer (2019-03-16). "When Poems of Resilience Get Twisted for Terrorism". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ "‘Invictus’ was among John Lewis’s favorite poems. It captures his indomitable spirit. Archived 2020-07-18 at the Wayback Machine." The Washington Post. 17 July 2020.

- ^ Duke of Sussex, Prince Harry (2023). Spare. Penguin Random House. ISBN 9780593593806.

- ^ Sayers, Dorothy (1943). Clouds of Witness. Classic Gems Publishing. p. 28. Retrieved 2014-05-15.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Casablanca Movieclips excerpt on YouTube

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook (30 January 2010). "British leaders: they're not what they were". The Daily Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 1 February 2010.

- ^ "Green Bay Packers". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2018-08-06.

- ^ "Daniel Craig, Tom Hardy & Will.i.am recite 'Invictus' to support the Invictus Games". YouTube. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ "When are Prince Harry's Invictus Games and what are they?". The Daily Telegraph. 8 May 2016. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

External links

[edit] Works related to Invictus at Wikisource

Works related to Invictus at Wikisource- The original untitled poem in Henley's A Book of Verses Archived 2023-04-24 at the Wayback Machine at Google Books.

Invictus public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Invictus public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Invictus

View on GrokipediaAuthor and Historical Context

William Ernest Henley's Biography

William Ernest Henley was born on 23 August 1849 in Gloucester, England, as the eldest of six children to William Henley, a bookseller, and his wife Mary Morgan.[7][8] He attended the Crypt Grammar School in Gloucester, where he showed early interest in literature under the influence of teacher T.E. Brown.[7] From age 12, Henley suffered from tuberculosis of the bone, which necessitated repeated surgeries on his left leg.[9] At around age 16, his left leg was amputated below the knee to halt the disease's progression.[2] In 1873, facing similar threats to his right leg, he traveled to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary for experimental antiseptic treatment under surgeon Joseph Lister, enduring 20 months of hospitalization that preserved the limb but left him with chronic pain and reliance on a wooden prosthesis.[2] During this period in 1875, Henley composed his renowned poem "Invictus," reflecting his defiance amid suffering.[2] Henley pursued a career in journalism and editing, contributing to publications like the London in the late 1870s and serving as editor of the Scots Observer from 1889, which relocated to London and became the National Observer until 1894.[9] He then edited the New Review until 1898, where he championed emerging writers including Rudyard Kipling and H.G. Wells, while promoting a robust, patriotic literary style.[10] His poetry collections, such as A Book of Verses (1888), established him as a Victorian poet emphasizing resilience and individualism. Henley formed a close friendship with Robert Louis Stevenson, who modeled the character Long John Silver partly on him and dedicated Treasure Island to Henley's family.[9] On 22 January 1878, Henley married Hannah Johnson Boyle, whom he met during his Edinburgh treatment; the couple had one daughter, Margaret Emma, born in 1888, who died of cerebral meningitis in 1894 at age five.[8][9] Despite ongoing health battles, Henley continued writing and editing until his death from tuberculosis on 11 July 1903 in Woking, Surrey, at age 53.[8]Personal Inspiration and Composition

William Ernest Henley composed "Invictus" in 1875 while hospitalized at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh for treatment of tuberculosis of the bone, a condition that had afflicted him since childhood.[1] Diagnosed at age 12, the disease progressed to necessitate amputation of his left leg below the knee at age 16 in 1865.[2] By 1873, the infection threatened his right leg, leading to a nearly 20-month stay where amputation loomed as a likely outcome.[1] [2] The poem emerged as the fourth part of a larger series of hospital reflections, though it was ultimately excluded from Henley's published "In Hospital" sequence.[1] Facing excruciating pain and the prospect of further disability, Henley drew on his determination to affirm personal resilience; his surgeon, Joseph Lister, employed innovative carbolic acid treatment to eradicate the infection, preserving the leg without surgery.[2] This intervention, rooted in Lister's pioneering antiseptic techniques, allowed Henley to avoid bilateral amputation and later walk with a crutch.[2] Originally untitled, the work received its Latin appellation "Invictus"—meaning "unconquered"—upon publication in 1888 as part of Henley's A Book of Verses.[1] The composition embodies Henley's defiance against bodily affliction, channeling his lived ordeal into verses emphasizing unconquerable will, independent of external circumstance or medical prognosis.[1] [2]Victorian Era Influences

The poem Invictus, composed in 1875 amid the Victorian era's cultural and intellectual ferment, embodies the period's valorization of personal fortitude and emotional restraint in confronting adversity. Victorian society, shaped by rapid industrialization, imperial expansion, and scientific challenges to religious orthodoxy—such as Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species published in 1859—fostered a cultural ethos emphasizing self-discipline and resilience over passive fatalism. Henley's assertion of an unconquerable soul despite "the bludgeonings of chance" mirrors this "stiff upper lip" ideal, a hallmark of Victorian stoicism that prioritized individual moral agency amid existential uncertainties.[11][12] This stoic inflection drew from a resurgence of interest in classical philosophy during the era, including Stoicism's focus on internal mastery, which resonated with Victorian thinkers like Matthew Arnold and influenced literature promoting self-reliance as a bulwark against social upheaval. Henley's own protracted battle with tuberculosis osteomyelitis, treated under primitive antiseptic conditions by surgeon Joseph Lister in the 1870s, exemplified the era's medical limitations and the imperative for personal endurance without reliance on supernatural intervention. The poem's rejection of blaming "Whatever gods may be / For my unconquerable soul" reflects the contemporaneous shift toward secularism and agnosticism, as scientific rationalism eroded unquestioned faith, compelling individuals to forge meaning through autonomous will.[13][9][11] Victorian literary realism, evident in Henley's hospital-inspired verses, further contextualizes Invictus' unflinching portrayal of suffering, diverging from Romantic escapism toward a gritty affirmation of human agency that aligned with the era's Protestant work ethic and imperial narratives of perseverance. Yet, this realism sometimes clashed with prevailing sensibilities, as Henley's stark depictions of pain tested Victorian readers' tolerance for unvarnished bodily and spiritual trials.[9][14]Text and Poetic Form

Full Text of the Poem

Out of the night that covers me,Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.[3] In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.[3] Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.[3] It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.[3]