Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Japanese hare

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

| Japanese hare[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| in March, in a park in Tsukuba, Japan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | Lepus |

| Species: | L. brachyurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lepus brachyurus Temminck, 1845

| |

| |

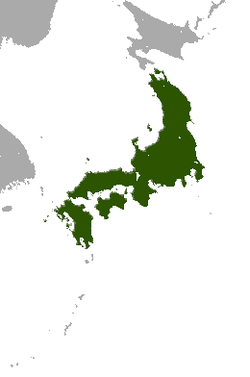

| Japanese hare range | |

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is a species of hare endemic to Japan. In Japanese, it is called the Nousagi (Japanese: 野兎), meaning "field rabbit".

Taxonomy

[edit]Coenraad Jacob Temminck described the Japanese hare in 1845. The specific epithet (brachyurus) is derived from the Ancient Greek brachys meaning "short"[3]: 708 and oura meaning "tail".[3]: 828

The four subspecies of this hare are:

- L. b. angustidens

- L. b. brachyurus

- L. b. lyoni

- L. b. okiensis

Description

[edit]The Japanese hare is reddish-brown, with a body length that ranges from 45 to 54 cm (18 to 21 in), and a body weight of 1.3 to 2.5 kg (2.9 to 5.5 lb). Its tail grows to lengths of 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in). Its front legs can be from 10 to 15 cm (3.9 to 5.9 in) long and the back legs from 12 to 15 cm (4.7 to 5.9 in) long. The ears grow to be 6 to 8 cm (2.4 to 3.1 in) long, and the tail 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in) long. In areas of northern Japan, the west coast, and the island of Sado, where snowfall is heavy, the Japanese hare loses its coloration in the autumn, remaining white until the spring, when the reddish-brown fur returns.

Habitat

[edit]The Japanese hare is found across Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, that is, all the main islands of Japan except Hokkaido,[4] where it is replaced by the related mountain hare (Lepus timidus). It occurs up to an altitude of 2700 m.[5] It is mostly found in mountains or hilly areas. It also inhabits forests or brushy areas. Japanese hares have been able to adapt to and thrive in and around urban environments following encroachment by human settlements, so much so that it has become a nuisance in some places.

Reproduction

[edit]The litter size of the Japanese hare varies from 1 to 6. The age of maturity is uncertain, but females probably breed within a year of birth. Breeding continues year round. Several litters are born each year, each of which contain 2–4 individuals. Mating is promiscuous; males chase females, and box to repel rivals.

Behavior

[edit]The Japanese hare, like most hares and rabbits, is crepuscular (feeds mainly in the evening and early morning). It is silent except when it is in distress, and gives out a call for the distress. It can occupy burrows sometimes. It is a solitary animal except during mating season, when males and females gather for breeding.

Food

[edit]Vegetation found in and around its habitat is where the Japanese hare gets most of its nutrients. Grasses, shrubs, and bushes are all eaten by the hare. The Japanese hare is one of the few hares that will eat the bark off of trees and it does so occasionally which can cause major damage to trees and forests. They will sometimes eat the bark from a bonsai tree in Asia.

Conservation

[edit]The Japanese hare population seems to be stable, though the quality or/and size of their habitat is decreasing. On a local level, they are used in hunting and specimen collecting. They are threatened by the creation of urban and industrial areas, water management systems, such as dams, hunting, trapping and invasive and non-native diseases and species. It is not known if they occur in any protected areas.[2]

Human interaction

[edit]In some places, it has become a pest. It is hunted in certain regions for food, fur, pelts, and to help curb its growing numbers.

The mythic Hare of Inaba has a place in Japanese mythology as an essential part of the legend of the Shinto god Ōkuninushi.

References

[edit]- ^ Hoffmann, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Yamada, F.; Smith, A.T. (2019). "Lepus brachyurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019 e.T41275A45186064. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T41275A45186064.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Brown, Roland Wilbur (1956). The Composition of Scientific Words. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ "Distribution map". IUCN.

- ^ Joseph A. Chapman; John E. C. Flux (1990). Rabbits, Hares and Pikas: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-2-8317-0019-9.

Japanese hare

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Systematics

Classification

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is a species within the genus Lepus, first described by Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck in 1844 as part of the Fauna Japonica by Philipp Franz von Siebold.[3] This description established it as a distinct entity based on specimens from Japan, distinguishing it from Eurasian hare species through its endemic morphological features.[3] The species belongs to the order Lagomorpha, family Leporidae, and genus Lepus; its subgenus placement remains uncertain, with debates suggesting possible inclusion in subgenus Allolagus (under Caprolagus) or Eulagos (under Lepus).[4] The genus Lepus encompasses around 30 hare species worldwide.[3] The specific epithet "brachyurus" derives from Ancient Greek "brachys" (short) and "oura" (tail), alluding to the animal's notably short tail compared to other hares.[5] Phylogenetically, L. brachyurus represents an early diverging lineage within Lepus, with molecular analyses of mitochondrial DNA indicating its separation occurred at the onset of the Pliocene epoch, around 5 million years ago.[6] It shares close affinities with other East Asian congeners, particularly the Korean hare (Lepus coreanus), forming a clade reflective of regional endemism, though historical taxonomic debates have occasionally linked it to broader Eurasian groups due to superficial similarities.[7] Recognition as a fully distinct species solidified through genetic and morphological evidence highlighting its isolation on the Japanese archipelago.[6]Subspecies

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is divided into four recognized subspecies, primarily distinguished by geographic isolation and associated morphological adaptations. These include L. b. brachyurus, L. b. angustidens, L. b. lyoni, and L. b. okiensis. Genetic studies indicate two main clades (northern and southern Japan) corresponding to these subspecies groups, with status supported by morphological analyses and genetic evidence indicating historical vicariance events, such as Pleistocene refugia, leading to localized differentiation despite some gene flow.[8][1] L. b. brachyurus (Temminck, 1844), the nominal subspecies, inhabits central and southern Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu. It features a year-round brownish pelage without seasonal whitening, along with relatively larger ears and hind feet compared to island populations.[9][8] L. b. angustidens (Hollister, 1912) is distributed in northern Honshu, particularly in heavy-snow regions along the Japan Sea side. This subspecies exhibits a seasonal coat color change from brown in summer to white in winter, an adaptation for camouflage in snowy environments, and tends to have a smaller skull size in males.[9][8] L. b. lyoni (Thomas, 1905) is endemic to Sado Island off northern Honshu. It displays a white winter coat similar to L. b. angustidens but shows increased body mass and length, reflecting insular conditions.[9][10] L. b. okiensis (Thomas, 1906) occupies the Oki Islands in the Sea of Japan. Individuals are larger in overall body size, head-body length, and mass than mainland counterparts—for example, females average 506 mm head-body length, 54 mm tail, 138 mm hindfoot, and 78 mm ear—but possess shorter ears, hind feet, and a smaller skull, adaptations possibly linked to insular environments.[9][11] These subspecies were initially described based on morphological traits like pelage variation and cranial measurements. Subsequent genetic studies using mitochondrial cytochrome b and nuclear markers have confirmed their isolation, with divergence estimates around 1 million years ago for some lineages, though admixture occurs between mainland forms.[8]Physical Characteristics

Morphology

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is a medium-sized lagomorph with a head-body length ranging from 45 to 54 cm, a weight of 1.3 to 2.5 kg, a tail length of 2 to 5 cm, and ear length of 6 to 8 cm.[1] These dimensions contribute to its agile build, adapted for swift evasion in varied terrains. Its fur is reddish-brown during summer, with white underparts providing camouflage against forest floors and undergrowth; the ears feature black tips year-round, while the tail has a white tip.[1] This coloration pattern aids in blending with the environment, though some northern subspecies exhibit seasonal whitening (detailed further in Seasonal Adaptations). Anatomically, the Japanese hare possesses elongated hind legs, measuring approximately 13.5 to 14 cm in hindfoot length.[1] Its large eyes, positioned laterally, provide a wide field of vision suited to crepuscular and nocturnal activity.[12] The dental structure includes continuously growing incisors—two pairs in the upper jaw (one large and one smaller peg tooth behind it)—with enamel only on the anterior surface, facilitating efficient herbivory through constant wear and renewal.[12]Seasonal Adaptations

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) undergoes pronounced seasonal pelage changes to adapt to environmental conditions, particularly in regions with snowfall. Populations in northern areas, such as the highlands of Honshu, molt from a brownish summer coat to a predominantly white winter pelage, enhancing camouflage against snow for predator avoidance. This molting process occurs twice per year, typically triggered by changes in day length (photoperiod) and temperature, reflecting phenotypic plasticity rather than fixed genetic differences between morphotypes.[13] In southern populations across Kyushu, Shikoku, and non-snowy parts of Honshu, the hare lacks this full white winter morph, maintaining a brown pelage year-round due to the absence of consistent snow cover. The white winter fur in northern individuals serves dual purposes: crypsis in snowy habitats and thermoregulation, as its airy structure provides greater insulation than the summer coat, reducing heat loss in cold weather. Physiologically, the species adjusts to winter through vascular control in its large ears, which conserve heat by reducing blood flow during cold periods while allowing dissipation in warmer conditions, aiding overall thermoregulation. While specific data on fat accumulation are limited, hares generally increase body reserves pre-winter to support energy demands when foraging is constrained by snow.Distribution and Habitat

Geographic Range

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is endemic to Japan and occupies the main islands of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, along with most surrounding islands such as Sado and the Oki Islands.[1] It is notably absent from Hokkaido, where the Arctic hare (Lepus timidus) fills a similar ecological niche.[1] Subspecies distributions align with this range, for instance L. b. angustidens in northern Honshu and L. b. okiensis on the Oki Islands.[1] The species' elevational range extends from sea level to approximately 2,700 m in subalpine and mountainous areas across its distribution.[1] This broad vertical span allows it to exploit diverse terrains, from coastal lowlands to high-elevation slopes.[14] Historically, the Japanese hare was more widespread in rural, forested, and open landscapes throughout its core islands, but urbanization and habitat fragmentation have caused range contractions, especially in peri-urban zones.[14] For example, in the Tama Hills region of Honshu, forest cover declined by about 20% from 1974 to 1994 due to residential development, leading to hare occupancy limited to larger forest patches exceeding 5.5 ha.[14] As of 2023, ongoing urban expansion continues to reduce suitable areas in urban fringes, contributing to localized declines, including concerns on Sado Island.[15][16]Habitat Preferences

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) primarily inhabits a variety of open and semi-open landscapes across its range in Japan, favoring grasslands, shrublands, and forest edges where herbaceous vegetation is abundant. It shows a strong preference for rural areas with dense ground cover, including young plantations of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica), which provide bright understories rich in grasses and herbs. These hares are also commonly found in agricultural edges and hilly terrains, adapting to human-modified environments such as suburban parks, though they largely avoid densely built urban centers.[1] In terms of microhabitat use, Japanese hares form resting sites, or "forms," in concealed locations such as under bushes, in dense scrub, or at the edges of forests to evade predators during the day. They select areas with low tree canopy closure and high volumes of understory vegetation for both shelter and mobility, often near water sources like rivers and streams. Elevations range from sea level up to 2,700 m, including alpine meadows in mountainous regions, where they utilize open grassy patches for cover.[1] Key habitat requirements include ready access to grasses for sustenance and dense escape cover to mitigate predation risks, with densities correlating positively with herb volume and negatively with canopy density. The species exhibits sensitivity to habitat fragmentation along rural-urban gradients, where landscape changes influence population distribution and abundance, as observed in studies from 2006 to 2016.[18][14]Ecology and Behavior

Daily and Social Behavior

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is primarily nocturnal, with activity often peaking during crepuscular periods (dawn and dusk) for foraging and movement. Individuals typically rest during the day in concealed locations such as dense scrub, brush, or shallow depressions known as forms, emerging to cover distances of up to approximately 1 km nightly within forested habitats and utilizing home ranges spanning 10–30 hectares.[19][1] Socially, the Japanese hare is largely asocial and solitary, with individuals avoiding prolonged interactions and maintaining spatial separation outside of transient encounters. While not true burrowers like rabbits, they occasionally seek shelter in abandoned burrows or natural cavities for protection during rest periods, relying on their strong hind limbs—adapted for rapid locomotion—to facilitate quick escapes when disturbed.[19][1] Communication among Japanese hares is predominantly non-vocal, depending on olfactory cues from scent marking as well as visual signals through body postures and ear movements to convey alertness or submission. In response to threats, they employ anti-predator strategies such as initial freezing to blend with surroundings, followed by explosive flight involving zig-zag runs at speeds reaching up to 50 km/h if pursued, or thumping hind feet to alert nearby individuals without vocalization.[19][1]Diet and Foraging

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is a herbivore with a diet primarily consisting of grasses, herbs, shrubs, and bark. During summer months, it feeds mainly on herbaceous vegetation, while in winter, snow cover limits access to ground plants, prompting a shift to browsing on thin branches and bark of shrubs and trees. Preferred food items include protein-rich shrubs such as Helwingia japonica (with 44.3% of browse marks observed) and Actinidia polygama (42.0%), as well as Staphylea bumalda and Rubus palmatus var. coptophyllus; feeding rates increase significantly with higher crude protein content in these plants (correlation r = 0.79, p < 0.001).[20] Foraging occurs primarily at night or during crepuscular periods, reflecting the species' nocturnal activity pattern, with hares selecting open shrub stands featuring high branch density and low canopy closure to facilitate access to food. Movement distances during foraging correlate positively with branch availability (r = 0.20, p < 0.05), but food caching is only weakly developed, unlike in some related species. This browsing behavior can lead to ecological impacts, including damage to agricultural crops through consumption and trampling, as well as feeding on forest seedlings like Chinese cedar (Cunninghamia lanceolata), where untreated damage causes up to 78% mortality in the first year. Occasionally, bark stripping affects trees in managed landscapes, contributing to localized forest degradation.[19][9] To maximize nutrient extraction from fibrous plant material, the Japanese hare engages in cecotrophy, re-ingesting soft, amorphous feces produced via hindgut fermentation during daytime rests in forms; hard feces, formed later in the colon, are also partially re-ingested through mastication for further breakdown. This adaptation recycles vitamins and proteins, enhancing overall digestive efficiency. Additionally, as a mobile herbivore, the Japanese hare plays a role in seed dispersal through endozoochory (viable seeds passed in feces) and epizoochory (seeds adhering to fur), promoting plant regeneration in its habitats—food availability for foraging is thus influenced by the shrub-dominated structure of preferred habitats.[21][22][20]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Breeding Patterns

The Japanese hare exhibits a prolonged breeding season. In the wild, it spans from early January to August, allowing for multiple reproductive cycles within a year.[1] In captivity, the season extends from early January to late October.[23] This extended period aligns with the species' opportunistic breeding strategy in temperate environments, though activity peaks during the warmer months. Females produce an average of 4.6 litters annually in captivity, with a range of 4 to 5 litters observed across individuals. In the wild, 2-3 litters per year have been reported.[23][16] Mating in the Japanese hare is promiscuous, with both males and females engaging multiple partners during the breeding season. Males exhibit aggressive behaviors to secure mates, including chasing females and boxing rivals with their forepaws to establish dominance. Copulations often occur in the evening, and females are induced ovulators, with postcoital ovulation triggered by mating, a characteristic trait among hares that facilitates rapid reproductive responses.[1][23] Litters consist of 1 to 4 young, with an average litter size of 1.6 reported from captive studies; in the wild, litter sizes are reported as 1-5 (average 2-3 in peak season), though data are limited.[23][1][16] The young are precocial, born fully furred, with eyes open, and capable of limited mobility shortly after birth. The gestation period averages 43.9 days, ranging from 43 to 45 days, enabling relatively short intervals between litters—sometimes as brief as 33 to 34 days due to potential superfetation. While wild litter sizes remain less documented than captive ones, these patterns suggest a reproductive output of approximately 7.4 young per female per year under controlled conditions.[23][1]Development and Growth

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) has a gestation period of 43 to 45 days, during which females carry litters averaging 1.6 young (range: 1–4). Leverets are born precocial, fully furred, and able to move independently within hours of birth, with an average birth weight of 135.9 g.[24] They begin consuming solid food approximately one week after birth and are weaned at 2 to 3 weeks, though nursing may continue for up to 4 weeks. Postnatal growth is rapid during the juvenile phase. Body weight increases at an average rate of 11.76 g per day initially, hind foot length at 0.73 mm per day, and ear length at 0.64 mm per day, with most external measurements approaching adult sizes by 100 to 300 days of age.[24] Sexual maturity is attained around 10 months.[1] Wild Japanese hares typically live 1 to 4 years, with high juvenile mortality driven by predation from foxes (Vulpes vulpes), Japanese martens (Martes melampus), and raptors such as golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos).[1] In captivity, individuals may survive up to 13 years under optimal conditions.[25]Conservation Status

Population Trends

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List, with its most recent global assessment dating to 2016 and populations described as stable overall.[1] The estimated total population size remains unknown, though the species is widespread across its native range in Japan, excluding Hokkaido and Okinawa.[26][3] Despite this stability, localized declines have been observed, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas. For instance, in green spaces around Tokyo, such as Nagaike Park in Hachioji City, hare sightings have sharply decreased over the past decade, with only one individual recorded on camera traps in 2022, signaling potential disappearance from some fragmented habitats.[27] No significant national or regional population updates have emerged in 2024 or 2025.[3] Population monitoring for the Japanese hare primarily depends on field-based methods, including camera trapping for density estimation and fecal pellet counts to assess distribution and abundance in various vegetation types.[28][29] However, challenges persist in obtaining precise numerical estimates and comprehensive data on occupancy within protected areas, limiting a full understanding of trends.[30]Threats and Protection

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) faces several threats, primarily driven by human activities and natural predation. Habitat loss due to urbanization and agricultural expansion has fragmented suitable grasslands and forest edges, reducing available foraging and shelter areas across its range in Japan.[31] A 2016 study along an urban gradient in the Tama Hills revealed that Japanese hares exhibit a time-delayed response to landscape changes, persisting in altered habitats for years before declining, which exacerbates vulnerability in rapidly developing regions.[18] Hunting for meat and fur, regulated under Japan's Wildlife Protection and Control Act, occurs during designated seasons with permits required, though it poses a lesser threat compared to habitat degradation.[32] Natural predators, including red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), Japanese martens (Martes melampus), and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), exert consistent pressure, particularly on juveniles.[1] Invasive species, such as the introduced Japanese marten (Martes melampus) on Sado Island, have caused significant local population declines through intensified predation.[26] Conservation efforts for the Japanese hare, classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List with stable overall populations, do not include federal protection as an endangered species.[2] However, the species benefits indirectly from Japan's network of national parks, such as Chichibu-Tama-Kai and Yoshino-Kumano, where habitat preservation and hunting restrictions maintain core populations. Studies on habitat fragmentation recommend establishing wildlife corridors to connect isolated forest patches, facilitating movement and genetic exchange in urbanizing landscapes.[18] No major national conservation initiatives specific to the Japanese hare have been implemented since 2023, though broader wildlife management under the Wildlife Protection and Control Act continues to regulate threats like invasive predators on islands.[33] Research gaps persist, particularly regarding the broader impacts of invasive species beyond isolated cases like Sado Island and the role of maturity age—estimated at around 10 months for females—in refining population viability models, which currently rely on limited demographic data.[1] These uncertainties highlight the need for enhanced monitoring to support proactive measures amid ongoing habitat pressures.Human Relations

Interactions and Uses

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) has been traditionally hunted in rural areas of Japan for its meat and fur, providing a source of food and pelts for local communities, particularly among traditional hunters like the Matagi in mountainous regions.[1][34][35] This practice dates back to historical utilization of game animals, including hares, in wild game cuisine known as gibier.[36] As an agricultural and forestry pest, the Japanese hare causes significant damage by consuming and trampling crops, as well as girdling young trees and saplings through bark stripping and bud feeding.[1][37] Their herbivorous diet, which includes grasses, herbs, and woody vegetation, exacerbates conflicts with farming and reforestation efforts, reported to affect over 250,000 acres (approximately 100,000 hectares) of young trees annually in the 1970s.[37] Management of Japanese hare populations focuses on localized control measures in farmlands and plantations, primarily through hunting to reduce numbers and limit damage, in line with Japan's Wildlife Protection and Hunting Law aimed at pest regulation.[33][37] Supplemental methods include physical barriers like nooses and chemical repellents such as cycloheximide applied to trees, though no large-scale commercial fur industry exists today, with utilization limited to traditional, small-scale harvesting.[1][37] However, as hares can carry zoonotic diseases such as tularemia and Q fever, proper handling and cooking of meat are recommended to mitigate health risks to hunters and consumers.[1]Cultural Role

The Japanese hare (Lepus brachyurus) holds a prominent place in ancient Japanese mythology, most notably in the "Hare of Inaba" tale recorded in the Kojiki, Japan's oldest extant chronicle from the early 8th century. In this story, a clever hare deceives a group of wani (crocodile-like sea creatures) into forming a bridge across the sea by having them lie side by side, allowing it to cross from the island of Oki to the mainland of Inaba; however, the last wani, enraged by the trickery, flays the hare's skin as punishment. The hare, left skinless and in agony, is then compassionately healed by the deity Okuninushi, who instructs it to bathe in freshwater and roll in sedge pollen to regrow its fur. Grateful, the hare—transformed into a divine messenger—prophesies Okuninushi's future marriage and success. This narrative symbolizes the hare's dual nature of cunning and vulnerability, illustrating themes of deception leading to suffering and redemption through benevolence, while the animal's shape-shifting into a prophetic figure underscores motifs of transformation and lunar-like cycles of renewal in Shinto lore.[38] Beyond mythology, the Japanese hare embodies lunar symbolism in Japanese folklore, often depicted as a white or ethereal figure residing on the moon, eternally pounding rice into mochi (glutinous rice cakes) with a mallet and mortar—a pattern visible in the moon's shadows according to traditional belief. This image derives from broader East Asian legends where a self-sacrificing rabbit (or hare) earns immortality by offering itself as food to a deity, who then places its silhouette on the moon as a symbol of charity, longevity, and selfless devotion; in Japan, this motif ties the hare to seasonal rituals like mochi-making during the New Year, evoking abundance and purity. Additionally, the hare's association with the moon extends to the Chinese zodiac, adopted in Japan as the Year of the Rabbit (or Hare), which recurs every 12 years and represents traits such as gentleness, quick wit, peace, and prosperity—qualities embodied by those born in such years, who are seen as kind, courageous, and harmonious.[39][34][40] In modern Japanese culture, the Japanese hare continues to inspire art, literature, and media, appearing in woodblock prints, netsuke carvings, and contemporary works that homage its mythological roots, such as ukiyo-e depictions of hares leaping over waves to symbolize vitality and good fortune. The 2023 Year of the Rabbit further amplified awareness of the species' cultural heritage while drawing attention to its ecological challenges, with exhibitions at institutions like the Tokyo National Museum showcasing hare motifs in historical art to foster appreciation and indirectly support conservation efforts amid reports of declining populations in urbanizing areas.[41][15]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/brachyurus