Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

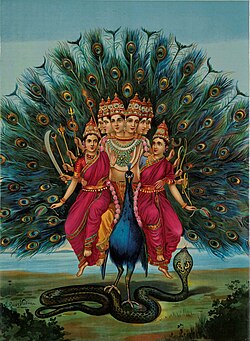

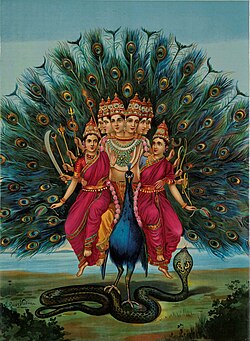

Kataragama deviyo

View on Wikipedia

Kataragama deviyo (also called: Skanda Kumara, Kartikeya, Sinhala: කතරගම දෙවියෝ, Tamil: கதிர்காமம் தேவன்) is a guardian deity of Sri Lanka. A popular deity who is considered to be very powerful, shrines dedicated to Kataragama deviyo are found in many places of the country.[1] Sinhalese Buddhists believe him also as a divine patron of the Buddha Sasana in Sri Lanka.[2] An ancient temple dedicated to God Kataragama, known as Ruhunu Maha Kataragama Devalaya is situated in the South-Eastern town of Kataragama in Monaragala District of Uva Province.

Today Ruhunu Maha Kataragama devalaya has become a temple which attracts and unites people of different religions and faiths.[3] Thousands of devotees from Sri Lanka and other parts of the world visit this temple daily.[4] Kataragama deviyo is identified with God Skanda of Hindu tradition, who is called as Murugan by the Tamil people. There is also an identical guardian deity of Mahayana Buddhism, known as Skanda. Theosophists identify Ruhunu Kataragama devalaya as a shrine which is dedicated to the lord of humanity and the world.[5]

Legends and beliefs

[edit]

Kataragama deviyo is native and long-celebrated in Sri Lankan lore and legend. Since ancient times an inseparable connection between Kataragama deviyo and his domain has existed. At some point in the history it is believed that he resided on the top of mountain Wedahitikanda, just outside the Kataragama town. The temple dedicated to Kataragama deviyo in Kataragama has been a place of pilgrimage and religious sanctity for thousands of years.

According to some legends God Kataragama originally lived in the Mount Kailash in Himalayas and had a divine consort by the name of Thevani, before moving to Kataragama in Sri Lanka. After settling down at Kataragama in South Eastern Sri Lanka, he had fallen in love with Valli, a beautiful maiden princess who had been raised by the indigenous Veddahs.[6] Later Valli became the second consort of God Kataragama and transfigured as a deity. Till today the indigenous Veddah people come to venerate Kataragama deviyo at the Kataragama temple complex from their forest abodes. His relationship to the Veddah princess Valli is celebrated during the annual Esala festival.

Balangoda Ananda Maitreya Thero, a scholar Buddhist monk who did research on Kataragama deviyo cult has revealed in his writings that Nilwakke Somananda Thero, who was the chief prelate of Mahabodhi temple in Madras, has managed to obtain Nadi wakya readings regarding God Kataragama. According to those Nadi astrology readings, Kataragama deviyo is a deity known as Subramanya or Subramanium who was sent to Sri Lanka by Gautama Buddha before his visits to the island.[7] During one of his visits to Sri Lanka, Buddha visited Kataragama area and delivered a discourse of Dhamma to the local people. Local residents were also advised to stop animal sacrifices widely practiced by them in that period. Buddha instructed the deity to reside in Sri Lanka and help the people when required, specially in their difficulties.[7] Wedahitikanda, a mountain in the area was selected as the place to stay for the deity. Thereafter the locals in Kataragama built a Buddhalaya (a shrine for Buddha) and a Devalaya (a shrine for Subrahmanya) to pay homage.

Another belief about God Kataragama is that King Mahasen of the Kingdom of Ruhuna later came to be worshiped as a deity. King Mahasen is believed to have built the Kiri Vehera Buddhist Stupa in Kataragama in the 6th century BC, after listening to the discourse of Dhamma delivered by Buddha.[8] In the Sinhalese tradition and culture local kings, rulers and ancestors who did a great service to the country or community were ordained as deities. Some of these deities are called as Bandara Devatha. They are respected and worshiped by certain villages and districts in Sri Lanka. Lot of Bandara Devathas are working under the Kataragama God. [9]

It is believed that the present spiritual residence of Kataragama deviyo lies in the jungles of south eastern Sri Lanka, where he is spending his time in meditation. The area known as Kebiliththa, located in the Yala National Park is one such location where devotees visit, after practicing strict religious rituals such as vegetarianism and abstinence to get the blessings of the god.[10] However, it is believed that Kataragama deviyo visits the Kataragama temple on special occasions, such as Eslala festival days and poya days.[10] Hence a minister of God Kataragama known as Kadawara deviyo, is believed to be the present guardian of the Kataragama temple.[11][12]

Kataragama devalaya

[edit]

According to legends, the Ruhunu Maha Kataragama Devalaya was built by king Dutugemunu around 160 B.C. as a fulfillment of a vow made before undertaking his successful military campaign against the Chola invader king Elara who was occupying the then Sri Lankan capital at Anuradhapura.[6][13] It is said that king Dutugemunu had obtained the blessings and guidance of God Kataragama to undertake his expedition against king Elara. After his victory, king Dutugemunu build the temple and dedicated it to God Kataragama. He also appointed the officials to look after the devalaya.[14]

The building of the Kataragama temple is a simple structure with two apartments and it has not undergone any major structural alterations after its construction.[13] It is a quadrangular building that is set in the middle of the large complex with outer walls of the temple premises have recurring and adorning figures of peacocks and elephants.[6] Next to the main temple are the temples dedicated to God Vishnu and God Ganesha. Another temple which is situated right to the Kataragama devalaya is dedicated to the goddess Thevani, a divine consort of God Kataragama.[15]

The Kiri Vehera, an ancient Buddhist stupa is situated in close proximity to the Kataragama temple. This religious structure probably dates back to the sixth century BC. The Bo tree which is situated behind the Kataragama temple is one of the eight saplings (Ashta Phala Ruhu Bodhi) of Sri Maha Bodhiya in Anuradapura, Sri Lanka. This sacred tree has been planted in the third century BC.[16] The Kiri Vehera Stupa is said to have been built by King Mahasen of the kingdom of Ruhuna, in the exact spot where the king met Buddha on his third and last visit to the island and listened to the sermon delivered by Buddha.[8][17]

Esala festival

[edit]The main event that is held to pay homage to Kataragama deviyo is the annual Esala Festival held at Kataragama in July or August. The traditional rituals of the annual Kataragama Esala festival starts with traditional Kap Sitaweema ceremony that take place at an auspicious time after the conclusion of Poson Poya day. Kap situweema is the installation of a sanctified log known as kapa at the premises of the temple. Devotees after having a bath in Menik Ganga (a river flowing near to the Kataragama temple) dressed in clean white clothes, walk across to the temple bearing offerings of flowers and fruit to the god, expect to obtain blessings to begin the Esala festival.[17]

Kataragama Esala Perehera is the most spectacular event of the annual Esala festival, which is held in the nights of festive season. A procession (perehera) with traditional dancers, kawadi dancers, drummers, fire walkers, elephants and many other religious rituals, it is known as one of the most elegant historical cultural pageants in Sri Lanka.[18] The fire-walking ceremonies for which the Kataragama festival is famous, take place in the main temple yard after the procession. The area is prepared with wood being burned beforehand and the devotees who take part in fire-walking, after having cleansed themselves and visited the main temple (maha devale) for divine blessings, tread the red-hot embers floored on the ground to show their great reverence to the god.[6]

The water-cutting ceremony that brings the festival to an official end is held in the Menik Ganga, the morning after the final procession take place on the full moon night. The final rite is the Diya Kapeema, where Kapurala (official of the temple) cut water of the river with a sword to ceremonially end the annual festival. Thereafter the devotees plunges into the shallow waters of Manik Ganga for purification, before departing to their everyday lives.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kariyawasam, A. G. S. (1995). "The Gods & Deity Worship in Sri Lanka". WWW Virtual Library - Sri Lanka. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Muesse, Mark W. (2011). The Hindu Traditions: A Concise Introduction. Fortress Press. pp. 113. ISBN 978-0-8006-9790-7.

- ^ Piyaratne, Nelson. "God Kataragama and his supreme identity". Daily News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ "On Foot by Faith to Kataragama". The Sunday Leader.

- ^ Pinkham, Mark Amaru (July–August 2007). "The Return of the King of the World". Atlantis Rising. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Sadanandan, Renuka. "Divine Power of God Kataragama". Serendib. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Wettasinghe, Samudra (2009). Ananda Maitreya Mahanahimiyange Aprakata Lipi. Sri Lanka: Tharanji printers. pp. 182–184. ISBN 978-955-0600-00-7.

- ^ a b Amarasekara, Janani (13 January 2008). "Blessed Kataragama". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ S.P.B.M. Ranasinghe (25 September 2020). "Bandara Devatha". Sri Lankan gods and goddesses, Lanka Wisdom.

- ^ a b Amarasinghe, Udeshi (November 2011). "Kebiliththa: Divine Belief". Explore Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Witane, Godwin (3 March 2001). "Kataragama: Its origin, era of decline and revival". The Island. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Sri Lankan Gods and Goddessess

- ^ a b Fernando, Lionel. "Ruhunu Kataragama Maha Devalaya". The Kataragama-Skanda website. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ Illankoon, Duvindi; Jeewandara, Shaveen. "Kataragama: Beyond the festival, a story of people and faith". Sunday Times. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Teyvani Amman Temple festivities at Kataragama". The Ceylon Daily News. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ "Kataragama". Travel Sri Lanka. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "Kataragama Esala Festival". Sunday Times. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ "Kataragama Esala festival begins in Southern Sri Lanka". ColomboPage. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- Bastin, Rohan (December 2002). The Domain of Constant Excess: Plural Worship at the Munnesvaram Temples in Sri Lanka. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-252-0.